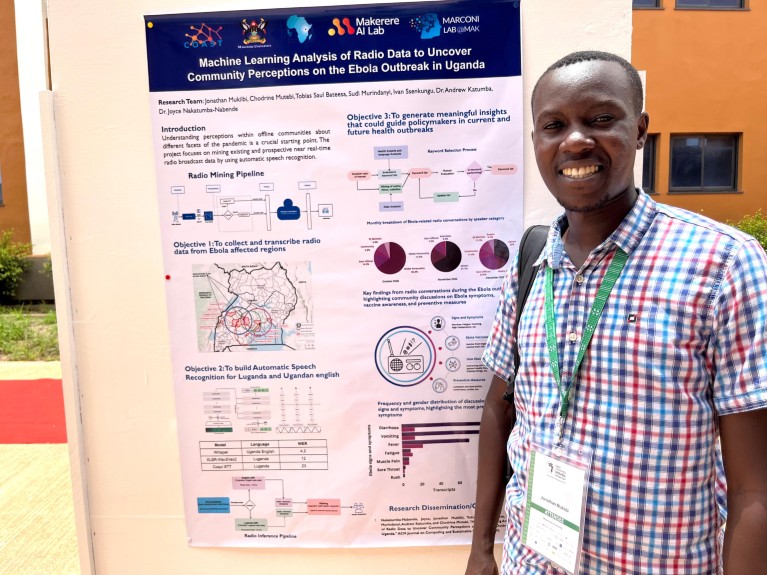

Jonathan Mukiibi of the Makerere Artificial Intelligence Lab at Makerere University in Kampala during a poster presentation at the Deep Learning Indaba 2024 conference in Senegal.Credit: Abdullahi Tsanni

Scientists have used AI to generate transcripts based on thousands of hours of radio broadcasts to discover what communities in Uganda perceive about Ebola outbreaks. Where internet penetration is low, people rely on the radio for information, so analysing what they are hearing is the first step to countering misinformation and shaping public health messaging.

When health authorities declared an Ebola outbreak in 2022, conspiracy theories began to swirl in communities across Uganda. Many people were mistrustful, and some expressed concern that the government was fabricating the epidemic, which had broken out just a year after a bitter election. Efforts to stop the spread were hampered and cases of the virus surged and spread, killing 53 people.

Computer scientist, Jonathan Mukiibi, of the Makerere Artificial Intelligence Lab at Makerere University, in Kampala, was troubled by the spread of misinformation on the internet during the outbreak, and felt Uganda’s response was missing the views of people who are offline.

“They don’t have access to the internet, so we can’t get their perceptions from social media,” Mukiibi says. That meant their views on the outbreak were unknown, isolated, and overlooked in response measures.

Mukiibi thought that if public health authorities knew what these people thought about the Ebola outbreak, they’d be able to tailor public health messaging and shape policies, and counter the spread of misinformation.

Only 40% of Africans are online. In Uganda, internet penetration is at 27%, according to a 2024 report. This means that about 36.5 million people are offline. Radio has penetrated hard-to-reach communities across Uganda, where over 55% of the population use it as their source of information. There are more than 200 licensed radio stations in the country. “Most of the people have a radio, so they can call or text into a radio station to express their opinions,” says Mukiibi. “In this case, if you don’t use radio, you have nothing.”

Mukiibi and his team trained machine learning models1 to listen hours of radio broadcast data and analyse community conversations surrounding the disease. To do this, they built a radio monitoring pipeline, which enabled them to stream audio from five community radio stations in Ebola affected districts for 17 hours a day for three months. The team fed the audio data into speech-to-text machine-learning models that they built in the local languages of Luganda and English.

The AI system generated transcripts of the conversations and timestamps of every word from speakers on the radio within two to three hours. Using a natural language processing (NLP) tool to classify the discussions in the transcripts, it uncovered meaningful insights that could help guide policymakers to develop target strategies in current and future health outbreaks. The next step was to build a dashboard to share insights with the Ministry of Health of Uganda and other researchers, highlighting symptoms, misinformation, and vaccine hesitancy issues.

Mukiibi and his team found that the radio conversations were largely dominated by government officials and media personalities during the 2022 Ebola outbreak, which lasted about three months. One implication of the lack of comment from scientists, says Mukiibi, was that because of a lack of trust in government, many Ugandans interpreted the Ebola outbreak as being linked to political and financial interests. The study also found that there was Ebola vaccine hesitancy, and community discussions focused on symptoms, and concerns over preventative measures instituted by the government such as lockdown, quarantine, and travel bans.

“I was excited to see the work,” says Elaine Nsoesie, associate professor of global health at Boston University, in Boston, Massachusetts. “In Africa, we have a strong oral storytelling tradition, and radio plays a key role in how people receive and share information. That makes it an important source to pay attention to in public health research,” she says.

Nsoesie, who is not part of the Makerere team, focuses her research on using unconventional data sources for public health. She says that the use of the radio data pipeline is valuable, with potential for real-time use of data to inform policy responses and mitigate misinformation. “That makes radio not only a communication channel but also a valuable data source for policymakers. By monitoring what people are asking, officials can design timely policy responses that directly address public concerns,” she says.

The research has raised some concerns. Nyalleng Moorosi, a computer scientist from Lesotho, who researches ethics and fairness in machine learning at the nonprofit the Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR), points out that this technology could potentially expose public radio users to human rights violations, especially in oppressive regimes. “It goes beyond [public] health – once a system like this exists, it can be used for other purposes such as monitoring political dissents,” she says.

Mukiibi says that the information obtained from the radio audio data is anonymised to protect individual privacy before sharing it with government and public health officials.

Now, Mukiibi’s team is aiming to build a broader system focused on community issues including health and agriculture. With support from Mozilla and using the Common Voice platform, they’re collecting limited speech data in a few local languages. Still, building robust speech recognition models across all these languages demands a massive investment in funds as well as data collection and model development to enable meaningful analysis of conversations across the country.

“The hope is that it will allow community development workers and advocates to select specific issues and receive insights and recommendations tailored to their communities,” says Mukiibi.