Harshita Bhatia excavating the fossil leaves. Credit: Gaurav Srivastava

A 23-million-year-old fossilized leaf found in coalfields in Assam is reshaping scientists’ understanding of how India’s biodiversity hotspots once connected. The discovery reveals that an evergreen forest corridor once stretched across the subcontinent, linking the Western Ghats in the south with the forests of the northeast1.

The fossil belongs to an ancient relative of Nothopegia, a genus now found only in the southern reaches of the Western Ghats. Its presence in the northeast offers evidence that species endemic to the southern mountains once had a far broader range, until dramatic shifts in climate and topography pushed them into ecological corners.

“This fossil captures a snapshot of a lost tropical corridor — a green highway that allowed species to move freely across India and mingle,” said Gaurav Srivastava, a paleobotanist at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences and lead author.

Srivastava, and his colleague, Harshita Bhatia, uncovered the fossil imprint at Tirap colliery in Assam’s Makum coalfields, amid blasting and rumbling machinery. The team used leaf anatomy, comparisons with modern specimens from Indian herbaria – the Central National Herbarium, Howrah; Forest Research Institute, Dehradun and online databases – and statistical analysis to identify the fossil as belonging to two new species: Nothopegia oligotravancorica and N. oligocastaneifolia.

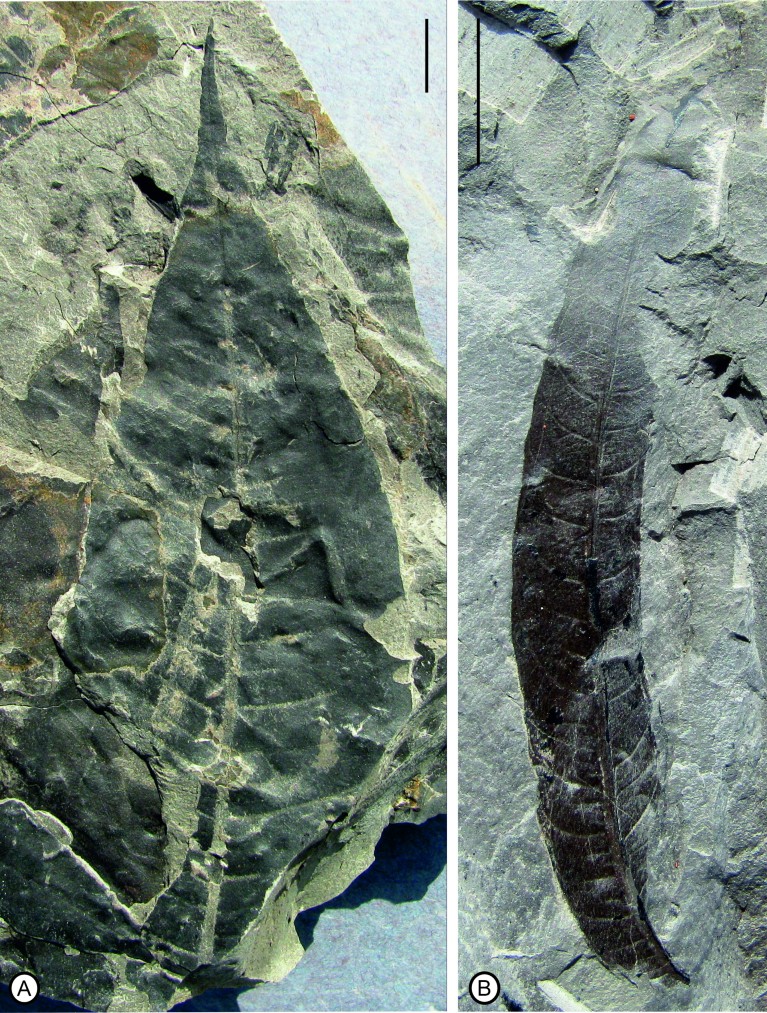

Fossil leaf of Nothopegia oligotravancorica (A) and Nothopegia oligocastaneifolia (B). Credit: Gaurav Srivastava & Harshita Bhatia

The fossil, preserved in deltaic swamp sediments dated to 24-23 million years ago, now represents the earliest known record of Nothopegia anywhere on Earth. Until this discovery, the oldest fossils of the genus came from Arunachal Pradesh.

The team’s reconstruction of the region’s ancient climate, based on fossil pollen, prehistoric plate tectonics, and modern comparisons, reveals a warm, humid landscape before the rise of the Himalayas and the onset of the South Asian monsoon. As tectonic upheaval pushed the Indian plate northward and lifted the mountains, temperatures fell, and once-lush forests in the northeast gave way to deciduous woodland. Nothopegia, vanished from the region.

But in the Western Ghats, conditions remained stable enough to harbour this relic lineage. “They continue to grow at the same latitudes today as their ancestors did in the northeast 23 million years ago,” Srivastava said. “That was the missing piece of the puzzle.”

The fossil’s story echoes through other endemic species in the Western Ghats. Plants like Poeciloneuron indicum and Holigarna beddomei also trace their roots to northeastern India, suggesting that the breakup of the ancient forest corridor helped drive the unique biodiversity of the Ghats.Climate change remains a looming threat. “Species that survived upheavals in deep time may not withstand the rapid changes we’re seeing today,” warned Mariana Vale, an ecologist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Her research shows that 84% of endemic mountain species face a high extinction risk if global temperatures rise by 3°C2.