Abstract

Background/Objectives

Individuals with a psychiatric disease have been reported to have structural variations in the retina, but how this affects retinal disease risk and vision loss is poorly understood. This study evaluated the risk of retinal disease and visual impairment in individuals with psychiatric disorders.

Subjects/Methods

An exploratory retrospective cohort study was conducted through a federated health research network that aggregates de-identified EHR data of over 95 million individuals across 50 healthcare organizations. Individuals ages 50–89 were identified for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), major depressive disorder (MDD), retinal disease, and visual impairment defined by vision loss or blindness using ICD-10 codes. Individuals were propensity score matched (PSM) on age, sex, race, ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemias. Risk ratio calculation and statistical analyses were conducted through the network’s analytics tool utilizing 95% confidence intervals.

Results

After PSM, the schizophrenia cohort had 160,414 matched individuals (average age 65), 391,440 in the BD cohort (64), and 1,962,380 in the MDD cohort (67). A recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with a decreased likelihood of having a retinal disease diagnosis, while recorded diagnoses of BD and MDD were associated with an increased likelihood. Across all psychiatric disorders, individuals with a retinal disease diagnosis had an increased risk of visual impairment compared to individuals with a retinal disease alone.

Conclusion

Recorded diagnoses of BD and MDD were associated with an increased likelihood of having a retinal disease diagnosis. Across all psychiatric disorders, individuals with a concurrent retinal disease were more likely to have a visual impairment diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), and major depressive (MDD), are chronic conditions that are detrimental to individual health and well-being. These disorders not only impose a substantial negative impact on the worldwide burden of disability and life satisfaction but have also been associated with increased risks of suicide, premature mortality, and modifiable coronary risk factors, such as obesity, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension [1,2,3,4,5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders worldwide has increased by more than 13% since 2007 and is only expected to rise [6].

The relationship between cerebral and ocular disease has been demonstrated to be one of significant clinical utility. Because the brain and the retina both develop from the neuroectoderm, they share many similar morphological and physiological properties. Therefore, changes within the retina may reflect pathological changes in the brain that are associated with cerebral disease. This allows the eyes to serve as a “window” to evaluate disorders originating from the brain [7]. Previous investigations have already found that retinal vascular change or degeneration was associated with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson disease, suggesting that neurological diseases impact ocular health and therefore these individuals should be screened and monitored for ocular manifestations [8, 9].

In addition to neurodegenerative disorders, psychiatric disorders have also been linked to changes within the eye, specifically the retina. Utilization of optical coherence tomography (OCT) in individuals with schizophrenia found notable retinal thinning and reduced macular thickness and volume [10,11,12,13]. In addition, OCT findings in individuals with BD have found significant global thinning of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) and lower ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL) volume [14,15,16]. When evaluating individuals with MDD using OCT, Kalenderoglu et al. found that these individuals had significantly reduced GCL, IPL, and global and temporal superior RNFL thickness [17]. These findings cumulatively shed light on how psychiatric disorders affect the structural component of the retina. However, how these structural abnormalities might lead to functional abnormalities and ultimately, retinal disease and subsequent visual impairment has not been thoroughly investigated.

A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan that explored the risk of retinal disease in individuals with BD found that this population was associated with a higher risk of retinal detachments, primary retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, and retinal vascular complications [18]. This study was conducted via records from a national Taiwanese database, highlighting the need for further investigation to assess if these findings are generalizable to the United States. The literature on the relationship between psychiatric and retinal disease is sparse, with this study being the only one to date that has explored the risk of retinal disease in individuals with a psychiatric disorder. This study did have limitations by only focusing on individuals with BD, being a relatively smaller study cohort, and evaluating a limited number of retinal diseases. As it is difficult to obtain large sample sizes of individuals with these more uncommon disorders at a singular institution, aggregated electronic health record research networks provides us the unique opportunity for a large group exploratory analysis.

This purpose of this exploratory analysis was to examine the risk of retinal disease in individuals with psychiatric disorders, specifically schizophrenia, BD, and MDD within a large aggregate electronic health records network. Retinal disease was defined as retinal conditions with an associated ICD-10 code (Supplementary Table 1) such as H35.32 for neovascular age-related macular edema (AMD). Additionally, this study explored how the presence of a psychiatric disorder affects the risk of visual impairment in individuals with a retinal disease.

Materials/subjects and methods

This population-based retrospective cohort study was conducted through the TriNetX Analytics Network, a federated health research network that aggregates the de-identified EHR data of over 95 million individuals across 50 healthcare organizations (HCOs). TriNetX, LLC is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the US federal law which protects the privacy and security of healthcare data, and any additional data privacy regulations applicable to the contributing HCO. The process by which the data is de-identified is attested to through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section §164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempt from Western Institutional Review Board approval. Data was collected over 2 weeks in May 2023.

This study compared individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), or major depressive disorder (MDD) (case) and those without such diagnoses (control) to assess whether they have different rates of receiving a diagnosis of retinal disease and visual impairment. The retinal diseases investigated were chronic or age-related conditions, such as diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and their associated complications (Supplementary Table 1). To target the population at the highest risk of developing these conditions and to allow sufficient time for these conditions to manifest, this study selected individuals aged 50 and older as the primary focus group [19, 20]. Individuals were evaluated up to age 89 because this database classifies individuals 90 and above as a protected population. The database was queried for any eligible individuals prior to a diagnosis index date of May 1st, 2023

All diagnoses data regarding psychiatric disorders, retinal disease, and visual impairment outcomes were extracted using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes. The ICD-10 codes used to determine the diagnoses of schizophrenia, BD, and MDD were F20, F31, and F32-33 respectively. The primary outcome measure of having a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease was defined by the ICD-10 codes, E10.31-E10.35, E11.31-E11.35, H31.0, and H33-H36. The secondary outcome measure of having a recorded diagnosis of visual impairment was determined by the ICD-10 code, H54. Additionally, specific retinal conditions were investigated including diabetic retinopathy (DR), chorioretinal scars, retinal detachment, retinal vascular occlusions, neovascular AMD, non-neovascular AMD, macular cyst or hole, cystoid macular degeneration, degenerative drusen of macula, puckering of macula, peripheral retinal degeneration, retinal hemorrhage, separation of retinal layers, retinal edema. Retinal disease and visual impairment diagnoses data were collected at person level, with no reference to eye laterality. All ICD-10 codes for these conditions are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

In order to determine how a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia, BD, or MDD may be associated with the risk of having a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease, we queried the dataset of eligible individuals to create a case cohort and a control cohort—the cases had the diagnosis of a particular psychiatric disorder of interest while the controls did not. In addition, individuals were stratified by age to best explore if age is associated with earlier onset of retinal disease within the study population. Age stratification by decade was performed to create sub-cohorts that were later compared to determine the risk ratio (RR) of having a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease in addition to specific retinal diseases. To determine how the colocalization of a psychiatric disorder with a retinal disease impacts a recorded diagnosis of visual impairment, we again queried the dataset of eligible individuals to create a case and control cohort – the case cohort had a recorded diagnosis of both a psychiatric disorder and retinal disease while the control cohort only had a history of a retinal disease but without a psychiatric disorder. For both sets of analyses, we provide an unadjusted RR in addition to an adjusted RR after propensity score matching (PSM).

One-to-one greedy matching algorithm with a calliper of 0.25 pooled standard deviations was utilized to perform PSM and incorporates multiple imputations for any missing pieces of data. Cohorts were matched on age, sex, race, ethnicity, hypertensive diseases (ICD-10 code: I10-I16), diabetes mellitus (E08-E13), and disorders of lipoprotein metabolism or dyslipidaemias (E78). The RR of having a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease and visual impairment and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and significant tests were 2-sided and paired. A significance threshold of 0.05 or less was used. All statistics analyses were conducted within the TriNetX analytics tool and forest plots were created in R Studio.

Results

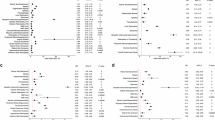

At the time of this study, this network had a total population of 38,824,237 for individuals age 50–89. Average age was 65 for individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia, 63 in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of BD, and 67 in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD. Additional demographics information can be found in Supplementary Table 2. After propensity score matching in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia, there were 55,163 individuals in the age 50–59 cohort; 62,479 individuals in the age 60–69 cohort; 31,573 individuals in the age 70–79 cohort; and 11,199 individuals in the age 80–89 cohort. The unadjusted RR of having a recorded diagnosis of retinal disease in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia was 2.03 compared to individuals without a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia (95% CI 1.99, 2.06). After age stratification and PSM, a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with a decreased likelihood of a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease across all age cohorts (Fig. 1a). Specifically, the adjusted RR was 0.90 for the age 50–59 cohort (95% CI 0.83, 0.96), 0.87 for the age 60–69 cohort (95% CI 0.83, 0.92), 0.91 for the age 70–79 cohort (95% CI 0.85, 0.97), and 0.82 for the age 80–89 cohort (95% CI 0.74, 0.91). Unadjusted and adjusted RR for specific retinal conditions in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

After PSM of the BD cohorts, there were 160,921 individuals in the age 50–59 cohort; 141,638 individuals in the age 60–69 cohort; 67,028 individuals in the age 70–79 cohort; and 21,853 individuals in the age 80–89 cohort. The unadjusted RR of having a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease in individuals with recorded diagnosis of BD was 1.81 compared to individuals without a recorded diagnosis of BD (95% CI 1.79, 1.83). After age stratification and PSM, a recorded diagnosis of BD was associated with an increased likelihood of a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease in the age 60–69, 70–79, and 80–89 cohorts (Fig. 1b). Specifically, the adjusted RR was 1.04 for the age 60–69 cohort (95% CI 1.01, 1.08), 1.15 for the age 70–79 cohort (95% CI 1.10, 1.20), and 1.15 for the age 80–89 cohort (95% CI 1.07, 1.23). Unadjusted and adjusted RR for specific retinal conditions in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of BD can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Among individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD, there were 645,256 matched individuals in the age 50–59 cohort; 658,244 in the age 60–69 cohort; 444,866 in the age 70–79 cohort; and 214,014 in the age 80–89 cohort. The unadjusted RR of having a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD was 4.22 compared to individuals without a recorded diagnosis of MDD (95% CI 4.20, 4.23). Even after adjusting for confounders, a recorded diagnosis of MDD was associated with an increased likelihood of a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease across all age cohorts (Fig. 1c). Specifically, the adjusted RR was 1.84 for the age 50–59 cohort (95% CI 1.79, 1.89), 1.70 for the age 60–69 cohort (95% CI 1.67, 1.74), 1.67 for the age 70–79 cohort (95% CI 1.64, 1.70), and 1.62 for the age 80–89 cohort (95% CI 1.58, 1.66). The unadjusted and adjusted RR for specific retinal conditions in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

Risk of visual impairment

After propensity score matching, there were 8880 individuals in the schizophrenia and retinal disease cohort; 22,678 individuals in the BD and retinal disease cohort; and 265,544 individuals in the MDD and retinal disease cohort. The unadjusted RR of visual impairment diagnosis in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia and a retinal disease was 1.90 compared to individuals with a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease alone (95% CI 1.81, 1.99). After matching, the adjusted RR of visual impairment diagnosis in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia and a retinal disease was 1.35 (95% CI 1.23, 1.48) (Table 1). The unadjusted RR of visual impairment diagnosis in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of BD and a retinal disease was 1.60 (95% CI 1.55, 1.65) compared to individuals with a recorded diagnosis of only a retinal disease. The adjusted RR of visual impairment diagnosis in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of BD and a retinal disease was 1.33 (95% CI 1.25, 1.42) (Table 2). Lastly, the unadjusted RR of visual impairment diagnosis in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD and a retinal disease was 1.98 compared to individuals with a recorded diagnosis of a retinal disease alone (95% CI 1.96, 2.00). After matching, the adjusted RR of visual impairment diagnosis in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD and a retinal disease was 1.51 (95% CI 1.48, 1.54) (Table 3).

The retinal disease with the highest adjusted RR of a recorded diagnosis of visual impairment in individuals with a recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia and BD was neovascular AMD at 1.94 (95% CI 1.11, 3.38) and 1.56 (95% CI 1.15, 2.12), respectively (Tables 1–2). For individuals with a recorded diagnosis of MDD, the retinal disease with the highest adjusted RR of a recorded diagnosis of visual impairment was DR at 1.55 (95% CI 1.51, 1.60) (Table 3). Additional RRs of visual impairment diagnosis for individuals with a recorded diagnosis of both a psychiatric and retinal condition can be found in Tables 1–3.

It is important to note that the associations noted in the study might relate to a variety of reasons which include a genuine association between a retinal and psychiatric disease through anatomical, genetic, and environmental risk factors and a genuine association between treatment of a psychiatric disorder and occurrence of retinal disease through psychotropic medications. Just as importantly, artefactual associations such as diagnostic variations across psychiatric disorders must be considered.

Discussion

This study utilized a large national database and examined individuals over 50 years old who were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder and retinal disease. In summary, we found that across each age cohort, recorded diagnoses of schizophrenia was associated with a decreased likelihood of recorded diagnoses of a retinal disease, while recorded diagnoses of BD and MDD was associated with an increased likelihood of recorded diagnoses of a retinal disease. However, concurrent diagnoses of a psychiatric disorder and retinal disease was associated with an increased likelihood of recorded diagnoses of visual impairment compared to individuals with a retinal disease alone.

Findings from existing studies suggest that psychiatric disorders may increase the risk of developing retinal disease by inducing anatomical and functional changes in the eye [21]. The literature acknowledges that individuals with schizophrenia, BD, and MDD exhibit a progressive loss of brain gray matter, and a growing body of emerging studies have begun to demonstrate that these populations also show retinal thinning on optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans and abnormal b-waves on electroretinogram (ERG) [13, 14, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Anatomically, because the retina is a direct extension of the brain tissue, it is plausible that the pathological mechanisms that mediate the loss of the brain tissue in psychiatric disorders could potentially exacerbate retinal degeneration and subsequent vision loss [32]. This degeneration may be caused by the imbalance of neurotransmitters—such as dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate—that occurs in psychiatric disorders, as neurotransmitter balance is crucial for not only retinal cell functions but also for maintaining the homeostasis of the ocular environment and thus cell survival [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Genetic factors may also play a role in inducing the anatomical changes of the retina in individuals with psychiatric disorders, potentially increasing the likelihood of developing a retinal disease. Rabe et al. determined that genetic susceptibility to schizophrenia revealed significant associations with retinal thinning while in individuals with BD, Ayik et al. demonstrated through their familial study that GCL and IPL thickness may be a suitable endophenotype candidate for the mood disorder [40, 41].

It is possible that this finding reflects an artefactual association, as individuals with schizophrenia may be less likely to be evaluated and diagnosed with a retinal condition due to poorer healthcare follow-up and greater executive function impairments in this population compared to those with BD and MDD [42,43,44,45,46]. In addition, individuals with schizophrenia are more likely to encounter obstacles in navigating healthcare services due to increased discrimination and financial limitations, which are not as prominent in individuals with BD and MDD [47, 48]. Furthermore, individuals with BD and MDD on average access care more readily in part because these conditions are more often recognized in primary care settings. Because schizophrenia management is reliant on more specialized services, which are less accessible in many regions, this can lead to fewer referrals to ophthalmology by primary care compared to individuals with a mood disorder [48, 49]. As the average life expectancy in individuals with schizophrenia is also shorter than in individuals with BD and MDD, the decreased likelihood of recorded retinal disease diagnoses in individuals with schizophrenia may also be explained by a Neyman bias [50, 51].

On the other hand, the associations observed in this study may also have underlying physiological mechanisms. For instance, dopamine, which is the main neurotransmitter that is increased in schizophrenia, may serve as a protective factor against retinal diseases in these individuals, as dopamine has been reported to have protective anti-oxidant properties and contribute to the regulation of the retinal circadian rhythm [52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. This hypothesis is supported by the decreased dopamine levels seen in individuals with MDD and this study’s finding that a recorded diagnosis of MDD is associated with an increased likelihood of being diagnosed with a retinal disease [59, 60]. In regard to the increased likelihood of recorded retinal disease diagnoses in individuals with BD, potential explanations include structural abnormalities. Individuals with BD have been noted to have a thinner peripapillary RNFL and combined ganglion cell layer and inner plexiform layer (GCIPL), features that have been implicated in retinal detachment as well as other neurodegenerative retinal diseases [15, 61,62,63,64].

Another potential explanation for the increased likelihood of retinal disease diagnoses in individuals with psychiatric disorders includes the use of psychotropic medications. Typical antipsychotics including thioridazine and chlorpromazine have been shown to cause pigmentary retinopathy which involves oxidative stress and damage to the retinal pigmental epithelium [65]. Atypical antipsychotics including olanzapine and aripiprazole, however, have been associated with retinal vein occlusion and retinal degeneration respectively [66]. Lastly, medications used for MDD including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been linked to ischemic disorders of the retina and optic nerve head especially in individuals with a history of atherosclerosis [67]. While individuals with schizophrenia are typically on psychotropic medications, artefactual associations such as poorer access to care in this population likely outweigh medication effects and could explain the decreased likelihood of receiving a retinal disease diagnosis.

However, across each psychiatric disorder, individuals with a retinal disease had an increased risk of visual impairment compared to individuals with a retinal disease alone. Factors including neurotransmitter dysregulation and structural abnormalities, that may increase the likelihood of receiving a retinal disease diagnosis could also play a role in exacerbating disease progression and promoting visual impairment [15, 37,38,39, 61,62,63,64]. Artefactual reasons that need to be considered include ocular treatment regimen non-adherence and lack of health-care follow-up, resulting in poor disease management and worse visual outcomes [68,69,70,71,72].

Individuals with psychiatric disorders are often considered a vulnerable population due to systemic, social, and biologic factors that contribute to worse health outcomes compared to the general population [4, 73, 74]. Psychiatric disorders are also associated with comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome that are known to increase risk of retinal disease such as diabetic retinopathy [75,76,77]. Our findings suggest the need for closer monitoring of retinal disease and visual impairment in individuals with psychiatric disorders.

Although this network provides us with a substantial sample size to explore the relationship between psychiatric disorders and retinal disease, it is not without limitations. This study is limited by its retrospective nature and potential variations in coding practices for retinal diseases among clinicians and institutions. As the ICD-10 codes for diagnoses of low vision or blindness in this study may not be consistently used in practice, this study’s results are likely an underestimation of the true extent of visual impairments. OCT and other visual outcome data such as visual acuity were also unavailable in the network database. Moreover, unaccounted differences in variables—such as medication usage, duration of psychiatric disorders, lifestyle factors like smoking, socioeconomic status, and healthcare access—between different cohorts may have introduced confounding effects that we were not able to control for. In addition, it is important to note that visual impairment has been suggested to exacerbate the progression of certain psychiatric disorders [78,79,80,81,82]. Future studies should take these confounders into consideration and are needed to better ascertain the extent to which the association between psychiatric and retinal disorders is attributed to genetic and physiologic causes as opposed to structural factors.

In conclusion, this exploratory retrospective cohort study highlights that while individuals with recorded diagnoses of schizophrenia were less likely to have recorded diagnoses of a retinal disease, individuals with recorded diagnoses of BD and MDD were more likely. However, across all psychiatric disorders, individuals with a concurrent retinal disease were more likely to have visual impairment compared to individuals with a retinal disease alone. Ultimately, these findings suggest closer ophthalmology monitoring may be warranted for patients with psychiatric conditions.

Supplementary material is available at Eye’s website.

Summary

What was known before

-

While patients with psychiatric disorders have been reported to have structural variations within the retina, the extent to which this puts patients at risk for retinal disease and vision loss has not been thoroughly investigated

What this study adds

-

Patients with schizophrenia are associated with a decreased risk of having a retinal disease while BD and MDD patients are associated with an increased risk.

-

However, across all these psychiatric disorders, patients with a retinal disease may be at risk for increased visual loss compared to patients with a retinal disease alone.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RIG, Möller HJ. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:412–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURPSY.2009.01.005.

Song Y, Rhee SJ, Lee H, Kim MJ, Shin D, Ahn YM. Comparison of suicide risk by mental illness: a retrospective review of 14-year electronic medical records. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e402. https://doi.org/10.3346/JKMS.2020.35.E402.

Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6.

Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–41. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2014.2502.

Meule A, Voderholzer U. Life satisfaction in persons with mental disorders. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:3043–3052. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11136-020-02556-9.

Mental health. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_2.

London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M. The retina as a window to the brain-from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:44–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRNEUROL.2012.227.

Choi S, Jahng WJ, Park SM, Jee D. Association of age-related macular degeneration on Alzheimer or Parkinson disease: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;210:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJO.2019.11.001.

Shariflou S, Georgevsky D, Mansour H, Rezaeian M, Hosseini N, Gani F, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of retinal biomarkers in early on-set Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14:1000–7. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205014666170329114445.

Lee WW, Tajunisah I, Sharmilla K, Peyman M, Subrayan V. Retinal nerve fiber layer structure abnormalities in schizophrenia and its relationship to disease state: evidence from optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7785–92. https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.13-12534.

Celik M, Kalenderoglu A, Sevgi Karadag A, Bekir Egilmez O, Han-Almis B, Şimşek A. Decreases in ganglion cell layer and inner plexiform layer volumes correlate better with disease severity in schizophrenia patients than retinal nerve fiber layer thickness: Findings from spectral optic coherence tomography. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;32:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURPSY.2015.10.006.

CABEZON L, ASCASO F, RAMIRO P, QUINTANILLA M, GUTIERREZ L, LOBO A, et al. Optical coherence tomography: a window into the brain of schizophrenic patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:0–0. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1755-3768.2012.T123.X.

Samani NN, Proudlock FA, Siram V, Suraweera C, Hutchinson C, Nelson CP, et al. Retinal layer abnormalities as biomarkers of Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:876–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHBUL/SBX130.

Mehraban A, Samimi SM, Entezari M, Seifi MH, Nazari M, Yaseri M. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in bipolar disorder. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:365–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00417-015-2981-7.

Garcia-Martin E, Gavin A, Garcia-Campayo J, Vilades E, Orduna E, Polo V, et al. Visual function and retinal changes in patients with bipolar disorder. Retina. 2019;39:2012–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000002252.

Kalenderoglu A, Sevgi-Karadag A, Celik M, Egilmez OB, Han-Almis B, Ozen ME. Can the retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL) volume be a new marker to detect neurodegeneration in bipolar disorder?. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;67:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPPSYCH.2016.02.005.

Kalenderoglu A, Çelik M, Sevgi-Karadag A, Egilmez OB. Optic coherence tomography shows inflammation and degeneration in major depressive disorder patients correlated with disease severity. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:159–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2016.06.039.

Hsu TW, Bai YM, Tsai SJ, Chen TJ, Liang CS, Chen MH. Risk of retinal disease in patients with bipolar disorder: A nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;76:106–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/PCN.13326.

Friedman DS, O'colmain BJ, Muñoz B, Tomany SC, McCarty C, de Jong PT, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHOPHT.122.4.564.

Lundeen EA, Burke-Conte Z, Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Saaddine J, Lee AY, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the US in 2021. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141:747–54. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAOPHTHALMOL.2023.2289.

Osborn DPJ. Topics in Review: The poor physical health of people with mental illness. West J Med. 2001;175:329–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/EWJM.175.5.329.

Yap TE, Balendra SI, Almonte MT, Cordeiro MF. Retinal correlates of neurological disorders. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319882205 https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622319882205.

Demmin DL, Davis Q, Roché M, Silverstein SM. Electroretinographic anomalies in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127:417–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/ABN0000347.

Jung KI, Hong SY, Shin DY, Lee NY, Kim TS, Park CK. Attenuated visual function in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM9061951.

Hébert M, Gagné AM, Paradis ME, Jomphe V, Roy MA, Mérette C, et al. Retinal response to light in young nonaffected offspring at high genetic risk of neuropsychiatric brain disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:270–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2009.08.016.

Hébert M, Mérette C, Paccalet T, Gagné AM, Maziade M. Electroretinographic anomalies in medicated and drug free patients with major depression: tagging the developmental roots of major psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;75:10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PNPBP.2016.12.002.

Bora E, Fornito A, Pantelis C, Yücel M. Gray matter abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder: a meta-analysis of voxel based morphometry studies. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2011.03.049.

Noga JT, Vladar K, Torrey EF. A volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study of monozygotic twins discordant for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2001;106:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4927(00)00084-6.

Moorhead TW, McKirdy J, Sussmann JE, Hall J, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC, McIntosh AM. Progressive gray matter loss in patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:894–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2007.03.005.

Wright IC, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff PWR, David AS, Murray RM, Bullmore ET. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. https://doi.org/10.1176/AJP.157.1.16.

Vita A, De Peri L, Deste G, Sacchetti E. Progressive loss of cortical gray matter in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal MRI studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e190. https://doi.org/10.1038/TP.2012.116.

Tan A, Schwitzer T, Conart JB, Angioi-Duprez K. Study of retinal structure and function in patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: A review of the literature. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020;43:e157–e166. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFO.2020.04.004.

Boccuni I, Fairless R. Retinal glutamate neurotransmission: from physiology to pathophysiological mechanisms of retinal ganglion cell degeneration. Life (Basel). 2022;12:638 https://doi.org/10.3390/LIFE12050638.

Zhou X, Li G, Zhang S, Wu J. 5-HT1A receptor agonist promotes retinal ganglion cell function by inhibiting OFF-type presynaptic glutamatergic activity in a chronic glaucoma model. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:448870 https://doi.org/10.3389/FNCEL.2019.00167/BIBTEX.

Mikheitseva IN. Imbalance of neurotransmitters in the rat retina under conditions of experimental glaucoma neuropathy. Neurophysiology. 2012;43:397–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11062-012-9240-X/METRICS.

Djamgoz MBA, Hankins MW, Hirano J, Archer SN. Neurobiology of retinal dopamine in relation to degenerative states of the tissue. Vis Res. 1997;37:3509–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00129-6.

Nutt DJ. Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:17337 https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/depression/relationship-neurotransmitters-symptoms-major-depressiveAccessed.

Carlsson M, Carlsson A. Schizophrenia: a subcortical neurotransmitter imbalance syndrome?. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:425–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHBUL/16.3.425.

Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Payne JL, Singh J, Lopes BP, Viegas JS, et al. The underlying neurobiology of bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry. 2003;2:136–46.

Rabe F, Smigielski L, Georgiadis F, et al. Genetic susceptibility to schizophrenia through neuroinflammatory pathways is associated with retinal thinning: Findings from the UK-Biobank. medRxiv. Published online April 6, 2024.04.05.24305387. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.05.24305387.

Ayık B, Kaya H, Tasdelen R, Sevimli N. Retinal changes in bipolar disorder as an endophenotype candidate: comparison of OCT-detected retinal changes in patients, siblings, and healthy controls. Psychiatry Res. 2022;313:114606 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114606.

Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, et al. Prediction of real world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1116–24. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.AJP.2010.09101406.

Ma M, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yan H, Zhang D, Yue W. Common and distinct alterations of cognitive function and brain structure in schizophrenia and major depressive disorder: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:705998 https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2021.705998.

Wingo AP, Harvey PD, Baldessarini RJ. Neurocognitive impairment in bipolar disorder patients: functional implications. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:113–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1399-5618.2009.00665.X.

Reichenberg A, Harvey PD, Bowie CR, Mojtabai R, Rabinowitz J, Heaton RK, et al. Neuropsychological function and dysfunction in schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:1022–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHBUL/SBN044.

Thomas FI, Olotu SO, Omoaregba JO. Prevalence, factors and reasons associated with missed first appointments among out-patients with schizophrenia at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Benin City. BJPsych Open. 2018;4:49–54. https://doi.org/10.1192/BJO.2017.11.

Lowther-Payne HJ, Ushakova A, Beckwith A, Liberty C, Edge R, Lobban F. Understanding inequalities in access to adult mental health services in the UK: a systematic mapping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12913-023-10030-8/FIGURES/3.

Akinhanmi MO, Biernacka JM, Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Balls Berry JE, Merikangas KR, et al. Racial disparities in bipolar disorder treatment and research: a call to action. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:506–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/BDI.12638.

Bizumic B, Gunningham B, Prejudice toward people with mental illness, schizophrenia, and depression: measurement, structure, and antecedents. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3. https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHIZBULLOPEN/SGAC060.

Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131:101–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCHRES.2011.06.008.

Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, Broadbent MT, Fernandes AC, Lee WE, et al. Life Expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS One. 2011;6:19590 https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0019590.

Doyle SE, Grace MS, McIvor W, Menaker M. Circadian rhythms of dopamine in mouse retina: the role of melatonin. Vis Neurosci. 2002;19:593–601. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952523802195058.

Goel M, Mangel SC. Dopamine-mediated circadian and light/dark-adaptive modulation of chemical and electrical synapses in the outer retina. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:647541 https://doi.org/10.3389/FNCEL.2021.647541/BIBTEX.

Cahill GM. Besharse JC. Circadian rhythmicity in vertebrate retinas: regulation by a photoreceptor oscillator. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1995;14:267–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/1350-9462(94)00001-Y.

Kesby JP, Eyles DW, McGrath JJ, Scott JG. Dopamine, psychosis and schizophrenia: the widening gap between basic and clinical neuroscience. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-017-0071-9. 2018 8:1.

Shibagaki K, Okamoto K, Katsuta O, Nakamura M. Beneficial protective effect of pramipexole on light-induced retinal damage in mice. Exp Eye Res. 2015;139:64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2015.07.007.

Yen GC, Hsieh CL. Antioxidant effects of dopamine and related compounds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:1646–9. https://doi.org/10.1271/BBB.61.1646.

Iida M, Miyazaki I, Tanaka KI, Kabuto H, Iwata-Ichikawa E, Ogawa N. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated antioxidant and neuroprotective effects of ropinirole, a dopamine agonist. Brain Res. 1999;838:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01688-1.

Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:327–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHPSYC.64.3.327.

Belujon P, Grace AA. Dopamine system dysregulation in major depressive disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:1036–1046. https://doi.org/10.1093/IJNP/PYX056.

Lizano P, Bannai D, Lutz O, Kim LA, Miller J, Keshavan M. A meta-analysis of retinal cytoarchitectural abnormalities in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:43–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHBUL/SBZ029.

Kurimoto Y, Kaneko Y, Matsuno K, Akimoto M, Yoshimura N. Evaluation of the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in eyes with idiopathic macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:756–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00960-0.

Laviers H, Li JO, Grabowska A, Charles SJ, Charteris D, Haynes RJ, et al. The management of macular hole retinal detachment and macular retinoschisis in pathological myopia; a UK collaborative study. Eye (Lond). 2018;32:1743–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41433-018-0166-4.

Barteselli G, Begum VU, Jonnadulla GB. Retinal ganglion cells thinning in eyes with nonproliferative idiopathic macular telangiectasia type 2A. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:1416–22. https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.14-15672.

Constable PA, Al-Dasooqi D, Bruce R, Prem-Senthil M. A review of ocular complications associated with medications used for anxiety, depression, and stress. Clin Optom (Auckl. 2022;14:13–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTO.S355091.

Mu C, Chen L. Characteristics of eye disorders induced by atypical antipsychotics: a real-world study from 2016 to 2022 based on Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1322939 https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2024.1322939.

Hayreh SS. Retinal and optic nerve head ischemic disorders and atherosclerosis:: Role of serotonin. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:191–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1350-9462(98)00016-0.

Loots E, Goossens E, Vanwesemael T, Morrens M, Van Rompaey B, Dilles T. Interventions to improve medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10213 https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH181910213/S1.

Deng M, Zhai S, Ouyang X, Liu Z, Ross B. Factors influencing medication adherence among patients with severe mental disorders from the perspective of mental health professionals. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12888-021-03681-6/TABLES/3.

Lassen RH, Gonçalves W, Gherman B, et al. Medication non-adherence in depression: a systematic review and metanalysis. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. Published online 2024. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2023-0680.

Sparr LF, Moffitt MC, Ward MF. Missed psychiatric appointments: who returns and who stays away. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:801–5. https://doi.org/10.1176/AJP.150.5.801.

Miller-Matero LR, Clark KB, Brescacin C, Dubaybo H, Willens DE. Depression and literacy are important factors for missed appointments. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21:686–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2015.1120329.

De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Cohen D, Asai I, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:52–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/J.2051-5545.2011.TB00014.X.

Lund C, Brooke-Sumner C, Baingana F, Baron EC, Breuer E, Chandra P, et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the sustainable development goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:357–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30060-9.

Cheung N, Mitchell P, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet. 2010;376:124–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62124-3.

Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diab Care. 2012;35:556–64. https://doi.org/10.2337/DC11-1909.

Lima-Fontes M, Barata P, Falcão M, Carneiro Â. Ocular findings in metabolic syndrome: a review. Porto Biomed J. 2020;5:104 https://doi.org/10.1097/J.PBJ.0000000000000104.

Demmin DL, Silverstein SM. Visual impairment and mental health: unmet needs and treatment options. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4229–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S258783.

Lundeen EA, Saydah S, Ehrlich JR, Saaddine J. Self-reported vision impairment and psychological distress in U.S. adults. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022;29:171–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2021.1918177.

Almonte MT, Capellàn P, Yap TE, Cordeiro MF. Retinal correlates of psychiatric disorders. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020;11:2040622320905215 https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622320905215.

Blazer DG, Hays JC, Salive ME. Factors associated with paranoid symptoms in a community sample of older adults. Gerontologist. 1996;36:70–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONT/36.1.70.

Hamedani AG, Thibault DP, Shea JA, Willis AW. Self-reported vision and hallucinations in older adults: results from two longitudinal US health surveys. Age Ageing. 2020;49:843–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/AGEING/AFAA043.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to MetroHealth & Dr. David Kaelber for access to the TriNetX Network.

Funding

This project was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative (CTSC); funded by the National Institutes of Health grant award UL1TR002548. This study was supported in part by the NIH-NEI P30 Core Grant (IP30EY025585), Unrestricted Grants from The Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., and Cleveland Eye Bank Foundation awarded to the Cole Eye Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC was responsible for the study design, manuscript writing, data collection, data analysis, and creating tables and figures. JKS was responsible for the study design, data analysis, creating tables and figures, and editing the manuscript. HJ was responsible for writing and editing the manuscript. RPS and KET were responsible for study design and reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RPS reports personal fees from Genentech/Roche, Alcon, Novartis, Regeneron, Asclepix, Gyroscope, Bausch and Lomb, Apellis. KET reports personal fees from Genentech/Roche, research fees from Zeiss and Regenxbio. AR reports consulting fees from Alcon, Genentech, Apellis, Iveric Bio, and Zeiss, speaking fees from Apellis, Genentech, and Regeneron, and research fees from AGTC, Apellis, Genentech, and NGM Bio.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, J., Shaia, J.K., Jeong, H. et al. Risk of retinal disease and visual impairment in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Eye (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03851-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03851-w