Abstract

Inherently chiral calixarenes hold great potential for applications in chiral recognition, sensing, and asymmetric catalysis due to their unique structures. However, due to their special structures and relatively large sizes, the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calixarenes is challenging with very limited examples available. Here, we present an efficient method for the enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral sulfur-containing calix[4]arenes through the desymmetrizing electrophilic sulfenylation of calix[4]arenes. This catalytic asymmetric reaction is enabled by a chiral 1,1’-binaphthyl-2,2’-diamine-derived sulfide catalyst and hexafluoroisopropanol. Various inherently chiral sulfur-containing calix[4]arenes are obtained in moderate to excellent yields with high enantioselectivities. Control experiments indicate that the thermodynamically favored C-SAr product is formed from the kinetically favored N-SAr product and the combination of the chiral sulfide catalyst and hexafluoroisopropanol is crucially important for both enantioselectivity and reactivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

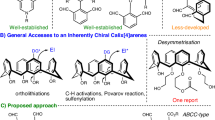

Due to the unique properties of sulfur, chiral organosulfur compounds are not only utilized as versatile synthons and catalysts/ligands1,2, but also widely present in bioactive compounds3,4, pharmaceuticals5,6, and functional materials7,8, Consequently, numerous methods have been developed for the preparation of chiral organosulfur compounds9,10,11. Lewis base catalyzed enantioselective electrophilic sulfenylation of alkenes represents an efficient and direct approach for constructing centrally chiral organosulfur compounds, which has been extensively studied by Denmark12,13,14,15,16, Zhao17,18,19,20, Chen21,22,23, and other research groups23,24,25,26,27. Recently, our group (Chen group) further explored Lewis base catalyzed asymmetric electrophilic aromatic sulfenylation as a practical and efficient method for synthesizing axially and planarly chiral organosulfur compounds28,29,30,31,32. However, catalytic asymmetric electrophilic sulfenylation methods for preparing inherently chiral sulfur-containing compounds with potentially unique properties remain unexplored and continue to pose challenges (Fig. 1a).

a State of the art of asymmetric electrophilic sulfenylation of arenes. b Previous work on catalytic asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes. c Our design for organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via an intermolecular electrophilic sulfenylation reaction. d Chiral sulfide catalyzed sulfenylation of calix[4]arenes. HFIP hexafluoroisopropanol.

In 1994, Böhmer and coworkers first introduced the concept of inherent chirality to describe calixarene frameworks lacking any symmetry element except a C1 asymmetry axis, distinguishing it from classical point, axial, planar, and helical chirality33,34,35,36. Due to their unique structures, inherently chiral calixarenes hold great potential for applications in chiral recognition, sensing, and asymmetric catalysis37,38,39,40,41. However, due to their special structures and relatively large sizes, the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calixarenes is challenging with very limited examples available, which has hindered subsequent functional studies35,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Early studies documented only two catalytic asymmetric examples by Mckervey and Tsue groups; however, the results were unsatisfactory52,53. In recent years, there has been increasing attention from synthetic chemists on developing catalytic enantioselective methods for constructing inherently chiral calixarenes with some elegant approaches being disclosed54,55,56,57,58,59,60. In 2020, Tong and Wang reported a highly enantioselective construction of inherently chiral heteracalix[4]aromatics using an intramolecular C − N bond forming strategy and they subsequently developed some other effective methods54,55,56. In 2022, Cai and coworkers developed a palladium-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular C − H arylation method producing inherently chiral calix[4]arenes in moderate yield with high enantioselectivity57. Shortly thereafter, a similar study was independently reported by Tong’s group (Fig. 1b)58. Very recently, two similar works on the enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via chiral Brønsted acid-catalyzed three-component Povarov reaction were reported59,60. Although these advances have been made, the strategies for synthesizing inherently chiral calixarenes are still lacking compared to abundant catalytic enantioselective methods for centrally and axially chiral molecules, and the development of new catalytic asymmetric systems is highly desirable.

Inspired by our previous successful examples of catalytic enantioselective electrophilic sulfenylation reactions and considering the potential special applications of inherently chiral sulfur-containing calixarenes, we are eager to explore the use of the desymmetrizing electrophilic sulfenylation reaction to prepare inherently chiral sulfur-containing calix[4]arenes (Fig. 1c). We anticipated encountering two primary challenges in achieving such highly selective transformations. Firstly, the similar nucleophilicity of N- and C-positions of anilines results in competitive chemoselectivity between the N- and C-positions during electrophilic sulfenylation. Secondly, the unique structures and large sizes of calix[4]arenes present difficulties in controlling enantioselectivity (Fig. 1c). To address these challenges, we propose the following strategies: (1) speculating that N-SAr products are kinetically favored while C-SAr products are thermodynamically favored, thus necessitating the establishment of a suitable reaction system capable of producing a single thermodynamically favored C-SAr product; and (2) designing a catalyst and/or developing cooperative catalysis that can effectively distinguish such special substrates through noncovalent interactions and/or steric hindrance to achieve high enantioselectivity control (Fig. 1c)61,62. Herein, we present a desymmetrizing electrophilic sulfenylation of calix[4]arenes using a combination of a chiral 1,1’-binaphthyl-2,2’-diamine (BINAM)-derived sulfide catalyst and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP). A variety of inherently chiral sulfur-containing calix[4]arenes were readily obtained in moderate to excellent yields with high enantioselectivities (Fig. 1d). Control experiments demonstrated that appropriate acidic conditions are essential for the formation of C-SAr product, and the combination of a chiral Lewis base and HFIP is crucial for controlling enantioselectivity.

Results

Reaction condition optimization

Initially, calix[4]arene amine derivative 2a was selected as the model substrate and compound 3a as the sulfenylating reagent to test our hypothesis. Following preliminary screening, p-toluenesulfonic acid (pTSA) and HFIP were selected as the acid promoters, with 3 Å molecular sieve (3 Å MS) used as the additive, and dichloromethane (DCM) employed as the solvent. As shown in Fig. 2, an array of chiral Lewis base catalysts were carefully investigated. To our delight, the BINAM-derived sulfide (S)–1a produced the desired product 4a in 89% yield with 77% ee. Remarkably, the N-SPh product 4a’, whose structure was determined by X-ray crystallography, was obtained in 87% yield using 1,1’-spirobiindane-7,7’-diamine (SPINAM)-derived sulfide (S)–1b as the catalyst. To clarify the underlying cause of this intriguing experimental outcome, we performed a series of control experiments (See Supplementary Fig. 18 for details). The findings demonstrate that catalyst (S)–1a exhibits significant catalytic activity as a Lewis base13, thereby facilitating the formation of 4a. Conversely, catalyst (S)–1b demonstrates diminished Lewis base activity, likely due to steric hindrance; nevertheless, it operates effectively as a Brønsted base that suppresses the formation of 4a. This result indicates competitive chemoselectivity in this system, consistent with our initial expectations. The use of 1,1’-bi-2-naphthol (BINOL)-derived sulfide (S)–1c significantly decreased both the yield and enantioselectivity. These three results suggest that the BINAM framework is suitable for this reaction. Subsequently, BINAM-derived selenide (S)–1d was tested as a catalyst, resulting in the desired product 4a being obtained in 74% yield with 64% ee. Therefore, several BINAM-derived sulfides with different amine moieties were subsequently examined, revealing that substituents at this moiety have a significant effect on enantioselectivity. N-isopropylcyclohexanamine slightly improved enantioselectivity while diphenylamine significantly diminished the enantioselectivity ((S)–1e vs (S)–1f). To our delight, the use of a compound with N-isopropyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-amine (S, R)–1g gave the product 4a in 93% yield with 91% ee. Utilizing (S, S)–1h as the catalyst, product 4a was obtained in 69% yield with 84% ee. The absolute configuration of this product is consistent with that observed for (S, R)–1g. These findings indicate that the absolute configuration of product 4a is determined by the chirality of the BINAM moiety present in the catalyst, while the chirality of the amine moiety primarily influence its enantioselectivity. Replacing N-isopropyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-amine with N-isopropyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-amine decreased enantioselectivity to 86% ee while maintaining 92% yield ((S, R)–1i). Finally, employing cyclohexane instead of isopropyl groups had a slight impact on enantioselectivity, but significantly affected the yield ((S, R)–1j). Thus, (S, R)–1g was chosen as the optimal catalyst.

Reaction conditions: unless otherwise noted, the reaction was conducted with 2a (0.1 mmol), 3a (0.12 mmol), Cat. (0.01 mmol), pTSA (0.01 mmol), HFIP (0.2 mmol), and 3 Å MS (40 mg) in DCM (2.0 mL) at −10 °C for 22 h under Ar. Isolated yields are shown. The ee values were determined by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). pTSA p-toluenesulfonic acid, HFIP hexafluoroisopropanol.

Substrate scope

Under the optimized conditions mentioned above, we initially explored the reaction scope by examining various sulfenylating reagents. To our satisfaction, all corresponding products were obtained with excellent yields and good enantioselectivities, except for product 4 m (4a–4r, Fig. 3). We observed that electron-withdrawing substituents such as fluorine, trifluoromethyl, and nitro at the para position of the benzosulfenyl group slightly improved the enantioselectivity, while electron-donating substituents such as methyl and methoxy decreased it (4b–4d vs 4e–4f). Substituent groups at the meta position had minimal impact on yield and enantioselectivity (4g–4k). Subsequently, We found that trifluoromethyl and methyl groups at ortho position reduced the yields and enantioselectivities (4m-4n), possibly due to steric hindrance. Sulfenylating reagent bearing a naphthyl group was well-suited for this system, yielding the desired product 4o with a high yield of 94% and an enantiomeric excess of 90%. The absolute configuration of 4o was determined to be (M) by X-ray crystallography. Furthermore, a range of calix[4]arenes with different aniline moieties were tested (4s–4ac). It was observed that substrates containing electron-rich aryl groups such as p-methylbenzene, p-tert-butylbenzene, and p-methoxybenzene performed well in this system, however, those with strong electron-deficient aryl groups such as p-trifluoromethylbenzene and p-acetylbenzene did not exhibit good compatibility (4v–4x vs 4t–4u). The desired C-SAr product demonstrates only a moderate yield, while both the N-SAr product and substrate are concurrently present in the system (4t or 4u). In the absence of a substituent on aniline, 4y was obtained in 63% yield with 69% ee, while the disulfenylated product 5y was also generated. This result again shows competitive chemoselectivity in this system. To our delight, multi-substituted phenyl moieties-containing substrates were well-tolerated, resulting in good yields and high levels of enantioselectivities (4z–4ab).

aThe reaction was conducted with 2 (0.1 mmol), 3 (0.12 mmol), (S, R)-1g (0.01 mmol), pTSA (0.01 mmol), HFIP (0.2 mmol), and 3 Å MS (40 mg) in DCM (2.0 mL) at −10 °C under Ar. Isolated yields are shown. The ee values were determined by HPLC or Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC). bThe reaction was performed at −20 °C. cThe reaction was performed at 0 °C. dThe reaction was performed at 10 °C. e(R, S)-1g (0.015 mmol) was used instead of (S, R)−1g. pTSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid, HFIP = hexafluoroisopropanol.

The use of benzylaniline 2ac as the substrate, the desired product 4ac was obtained in 85% yield with only 64% ee, which suggests that the diphenylamine moiety is important for controlling enantioselectivity. To further expand the scope of this transformation, we subsequently tested some substrates bearing different alkoxy groups and found that they worked well in this system with corresponding products generated efficiently and with high levels of enantioselectivity (4ad–4ah). Finally, product ent–4a was obtained in 93% yield with 90% ee when (R, S)–1g was used instead of (S, R)–1g.

Mechanistic studies

To gain mechanistic insights into this reaction, particularly regarding the high chemo- and enantioselectivity of the transformation, a series of control experiments were conducted (Fig. 4). The impact of the chiral Lewis base catalyst was first investigated (Fig. 4a). It was observed that products 4a and 4a’ were simultaneously obtained in moderate yields when the reaction was carried out without the chiral Lewis base (S, R)–1g (entry 2), indicating a racemic background reaction. Interestingly, it was found that neither the Lewis base, pTSA nor HFIP could selectively promote the formation of product 4a alone (entries 3-5). Surprisingly, product 4a’ was smoothly obtained in 85% yield in the absence of Lewis base, pTSA, and HFIP over a period of 22 hours (entry 6). Based on these results, we speculated that acidic conditions can promote the formation of product 4a (entry 2 vs entries 3-6).

a The effect of chiral Lewis base catalyst. b The effect of acid. c The effect of HFIP. d The effect of N-H group of the substrate. e Kinetic experiment (blue line for 4a’, orange line for 4a, green line for 2a). f The conversion from 4a’ to 4a. Standard conditions: The reaction was conducted with (S, R)-1g (0.01 mmol), pTSA (0.01 mmol), HFIP (0.2 mmol), and 3 Å MS (40 mg) in DCM (2.0 mL) at −10 °C under Ar for 22 h. pTSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid, PA = 1,1’-binaphthyl-2,2’-diyl hydrogenphosphate, HFIP = hexafluoroisopropanol.

We subsequently assessed the impact of acid on this reaction (Fig. 4b). It was observed that regardless of the type of acid used, product 4a consistently yielded high enantioselectivities and good yields (entries 1–5). Even in the absence of added acid, product 4a was formed smoothly alongside product 4a’ (entry 6). These findings suggested that acid influences reactivity but not enantioselectivity, further confirming the favorable role of acidic conditions in the formation of product 4a. Given HFIP’s potential as an acid promoter63,64,65,66,67, it was hypothesized that additional HFIP could lead to the separate formation of product 4a without added acid. Encouragingly, experimental results supported this hypothesis (entry 7).

Next, we conducted a further assessment of the impact of HFIP in this reaction (Fig. 4c). In the absence of HFIP, the desired product 4a was only obtained in 28% yield with 70% ee, while product 4a’ was produced in 69% yield (entry 2). The reaction of 2a with an additional 0.2 equiv of pTSA, without HFIP, resulted in an increased yield of product 4a to 47% while maintaining 70% ee (entry 3). Conversely, using isopropanol instead of HFIP led to a decreased yield of the product to only 20%, despite maintaining 71% ee (entry 4). When substrate 2a was treated with trifluoroethanol, whose properties closely resemble those of HFIP, the expected result was achieved: product 4a was obtained in 83% yield with 89% ee (entry 5). However, either 4,4,4-trifluorobutan-1-ol, 5,5,5-trifluoropentan-1-ol, or bis(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl) ether was used instead of HFIP, the yield and enantioselectivity of product 4a were consistently diminished (entries 6-8). These findings suggested that HFIP not only functions as an acid promoter but also plays a crucial role in controlling both chemo- and enantioselectivity. Additionally, we found that the free N − H group of the substrate is indispensable to the reaction (Fig. 4d).

To further investigate the origin of chemoselectivity, we conducted kinetic experiments (Fig. 4e). The results revealed complete consumption of substrate 2a within ten minutes, leading to the formation of a significant amount of 4a’, accompanied by a minor formation of 4a. Subsequently, 4a’ was gradually consumed with an increasing generation of 4a until complete consumption of 4a’. Based on these findings, it is inferred that product 4a’ is kinetically favored while product 4a is thermodynamically stable, and that conversion from 4a’ to 4a occurs during the reaction (See Supplementary Figs. 23, 24 for details). To further validate the conversion process of 4a’ to 4a, compound 4a’ was subjected to the standard conditions without the addition of sulfenylating reagent 3a, resulting in a 65% yield of product 4a with an 85% ee (Fig. 4f). It is believed that the lower yield and enantioselectivity of product 4a were due to the incomplete simulation of the real reaction system. Subsequently, by adding 0.2 equiv of sulfenylating reagent 3a and 1.0 equiv of saccharin to the reaction, which better mimicked the real reaction system, product 4a was obtained in an improved yield of 83% with a higher enantiomeric excess of 91%. These results further confirmed that compound 4a is indeed derived from compound 4a’. Furthermore, compound 4a’ was then performed under the standard conditions in the presence of 0.5 equiv of substrate 2ag, and product 4a was obtained in 19% yield with 83% ee, accompanied by 4ag in 31% yield with 85% ee. These results suggested that the conversion of 4a’ to 4a is likely to undergo an intermolecular process.

Proposed mechanism

Previous studies68,69 have demonstrated that HFIP and pTSA are involved in a network of hydrogen bond interactions, which can significantly influence both reactivity and selectivity. Consequently, we conducted a series of hydrogen bond titration experiments involving HFIP with pTSA, HFIP with 3a, pTSA with 3a, as well as the combination of HFIP, pTSA, and 3a. The experimental results indicate that hydrogen bonds may be present between HFIP and pTSA, as well as between pTSA and 3a; however, no significant hydrogen bond interaction was observed between HFIP and 3a. Naturally, the combination of HFIP, pTSA, and 3a could exhibit a network of hydrogen bond interactions (See Supplementary Figs. 25–28 for details). Subsequent kinetic investigations suggest that the reaction order in HFIP is approximately 2.2 (See Supplementary Figs. 29–37 for details). In light of the results from the aforementioned experiments, a proposed mechanism is depicted in Fig. 5. Initially, the activated species int-1 is generated through hydrogen bond interactions among 3a, pTSA, and HFIP. Subsequently, catalyst (S, R)–1g reacts with int-1 to yield intermediate int-2, which then rapidly forms the kinetic product 4a’ in the presence of substrate 2a. Our experimental results demonstrate that while 4a’ can be generated slowly in the absence of a catalyst, its production rate is significantly enhanced by the synergistic effects of catalysts (S, R)–1g, pTSA, and HFIP (See Supplementary Figs. 19, 20 for details). This process is reversible; regenerated int-2 can attack substrate 2a to produce intermediate int-3 via transition state TS-1-M (favored). Based on our previous research29 and hydrogen bond titration experiments (See Supplementary Fig. 39 for details), we propose that the formation of a hydrogen bond between the N − H group of the substrate and the pTSA anion/HFIP species (A−) may reduce the energy barrier for this reaction and contribute to stabilizing TS-1-M. In another transition state TS-1-P (disfavored), steric hindrance between the naphthalene framework of the catalyst and substrate 2a renders it unfavorable for generating a (P)-configured product. Subsequently, deprotonation of intermediate int-3 by A− through transition state TS-2 results in the formation of thermodynamically favored product 4a while releasing HFIP and pTSA as well as regenerating the catalyst.

Gram-scale reaction and synthetic applications

To demonstrate the synthetic applicability of this reaction, a gram-scale reaction of substrate 2a was conducted under standard conditions. As depicted in Fig. 6a, the product 4a was obtained in 97% yield with 90% ee. In comparison to sulfides, sulfoxide and sulfone compounds often showcase distinct bioactivities; therefore, we proceeded to synthesize sulfoxide and sulfone compounds. The sulfoxide 7a was obtained in 93% yield and an approximately 3:1 diastereomeric ratio with 90% ee using 1.0 equiv of 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) at −20 °C (Fig. 6b). Sulfide 4a underwent reaction with 3.0 equiv of mCPBA, yielding sulfone compound 8a in 93% yield with 90% ee (Fig. 6c). Ultimately, the benzyl group can be effectively cleaved from 4ac in the presence of DDQ at 0 °C, yielding aniline derivative 9a in 80% yield with 95% ee (Fig. 6d).

a The reaction was conducted with 2a (1.43 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 3a (1.72 mmol, 1.2 equiv), (S, R)-1g (0.143 mmol, 0.1 equiv), pTSA (0.143 mmol, 0.1 equiv), HFIP (2.86 mmol, 2.0 equiv), and 3 Å MS (572 mg) in DCM (28.6 mL) at −10 °C under Ar for 22 h. b The reaction was conducted with 4a (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), mCPBA (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), and NaHCO3 (0.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv) in DCM (2 mL) at −20 °C under Ar for 24 h. c The reaction was conducted with 4a (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and mCPBA (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv) in DCM (2 mL) at rt under Ar for 7 h. d The reaction was conducted with 4ac (0.012 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and DDQ (0.024 mmol, 2.0 equiv) in DCM (0.5 mL) and H2O (0.1 mL) at 0 °C under Ar for 1.5 h. pTSA p-toluenesulfonic acid, HFIP hexafluoroisopropanol, mCPBA = 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, DDQ = 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano−1,4-benzoquinone.

Photophysical and chiroptical properties

Next, we examined the photophysical properties of sulfide product 4o and sulfone product 8a. The UV-vis spectra of 4o and 8a exhibited similar strong absorption peaks at approximately 230 nm and the lowest absorption peak at around 340 nm (Fig. 7a). Upon excitation at their respective maximum wavelengths (315 nm for 4o and 360 nm for 8a), both compounds displayed broadened fluorescence emission bands, with peaks observed at 400 nm for 4o and at 453 nm for 8a (Fig. 7b). Additionally, the quantum yields were determined to be 0.097 for 4o and 0.092 for 8a, respectively. Subsequent investigation into the chiroptical properties of (P/M)–4o and (P/M)–8a was conducted using circular dichroism (CD) and CPL spectroscopy (Fig. 7c–e). As depicted in Fig. 7c, a positive Cotton effect was observed at 250 nm along with two negative effects at 298 nm and 349 nm for (M)–4o; while a positive Cotton effect was observed at 350 nm along with two negative effects at 247 nm and 290 nm for (M)–8a were clearly observed. Enantiomers (P)–4o and (P)–8a showed the expected mirror-imaged CD spectrum. The CPL spectra results showed that (P/M)–4o and (P/M)–8a were all CPL-active and produced clear mirror-image spectra (Fig. 7d, e). Finally, the luminescence dissymmetry factors |glum| values at 315 nm were measured to be 1.0 × 10−3 for (P/M)–4o and 1.2 × 10−3 at 360 nm for (P/M)–8a (Fig. 7f–h). These results are in accord with conventional circularly polarized luminescent materials with typical |glum| values on the order of 10−5–10−3.

a Absorption spectra of 4o and 8a in n-hexane (1.0 × 10−5 M) (purple line for 4o, blue line for 8a). b Emission spectra of 4o and 8a in n-hexane (1.0 × 10−4 M) (purple line for 4o, blue line for 8a). c CD spectra of (P/M)-4o and (P/M)-8a in n-hexane (1.0 × 10−5 M) at room temperature (purple and red line for (M)−4o and (P)-4o, blue and green line for (M)−8a and (P)-8a). d CPL spectra of (P/M)−4o in n-hexane (1.0 × 10−4 M) at room temperature (excited at 315 nm) (purple line for (M)−4o, red line for (P)-4o). e CPL spectra of (P/M)−8a in n-hexane (1.0 × 10−4 M) at room temperature (excited at 360 nm) (blue line for (M)−8a, green line for (P)-8a). f glum values−wavelength curve for (P/M)−4o (purple line for (M)−4o, red line for (P)−4o). g glum values−wavelength curve for (P/M)−8a (blue line for (M)−8a, green line for (P)−8a). h Structures and glum values for 4o and 8a. CD spectra = circular dichroism spectra. CPL spectra = circularly polarized luminescence spectra. glum = luminescence dissymmetry factors.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully developed an efficient method for the enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral sulfur-containing calix[4]arenes through desymmetrizing electrophilic sulfenylation. A chiral BINAM-derived sulfide was investigated as a suitable Lewis base catalyst. It was observed that the kinetically favorable product is rapidly formed while the thermodynamically favorable product is gradually formed from the former. The combination of a chiral Lewis base and HFIP plays an important role in controlling the enantioselectivity. The use of chiral Lewis base catalyzed electrophilic sulfenylation reaction to synthesize other useful chiral organosulfur compounds is ongoing in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for the catalytic asymmetric electrophilic sulfenylation of substrates 2

In an over-dried 10 mL tube added 3 Å MS (40 mg, grinded by mortar) and activated by heat gun, then equipped with a stir bar, corresponding calix[4]arene 2 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sulfenylating reagent 3 (0.12 mmol, 1.2 equiv), (S, R)–Cat. 1g (0.01 mmol, 0.1 equiv) and pTSA (0.01 mmol, 0.1 equiv) were added in one portion. HFIP (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was dissolved in DCM (2 mL) and added via syringes immediately at corresponding temperature, and the solution was stirred for several hours under argon atmosphere. After the reaction was complete (monitored by TLC), the mixture was quenched with triethylamine (30 μL) and stirred for additional 3 min. The solvent was removed under reduce pressure, and the crude product was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (petroleum ether: EtOAc) to afford the corresponding product 4.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information file. The experimental procedures, data of NMR, HRMS and HPLC have been deposited in Supplementary Information file. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, under deposition numbers 2342718 (for 2a), 2342717 (for 4a’), 2342716 (for 4o). These data could be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif). All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Masdeu-Bulto, A. M., Diéguez, M., Martin, E. & Gómez, M. Chiral thioether ligands: Coordination chemistry and asymmetric catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 242, 159–201 (2003).

Otocka, S., Kwiatkowska, M., Madalińska, L. & Kiełbasiński, P. Chiral organosulfur ligands/catalysts with a stereogenic sulfur atom: Applications in asymmetric synthesis. Chem. Rev. 117, 4147–4181 (2017).

Chatgilialoglu, C. & Asmus, K. D. Sulfur-centered reactive intermediates in chemistry and biology (Springer Verlag, New York, 1991).

Nagy, P. Recent advances in sulfur biology and chemistry. Redox Biol. 63, 102716 (2023).

Feng, M., Tang, B., Liang, S. H. & Jiang, X. Sulfur containing scaffolds in drugs: synthesis and application in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 16, 1200–1216 (2016).

Scott, K. A. & Njardarson, J. T. Analysis of US FDA-approved drugs containing sulfur atoms. Top. Curr. Chem. 376, 5 (2018).

Zhou, Y., Zhu, Z., Zhang, K. & Yang, B. Molecular structure and properties of sulfur-containing high refractive index polymer optical materials. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 44, 2300411 (2023).

Wang, M. & Jiang, X. Prospects and challenges in organosulfur chemistry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 671–677 (2022).

Matviitsuk, A., Panger, J. L. & Denmark, S. E. Catalytic, enantioselective sulfenofunctionalization of alkenes: Development and recent advances. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 59, 19796–19819 (2020).

Liao, L. & Zhao, X. Indane-based chiral aryl chalcogenide catalysts: Development and applications in asymmetric electrophilic reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2439–2453 (2022).

Cao, R.-F. & Chen, Z.-M. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of sulfur-containing atropisomers by C–S bond formations. Sci. China Chem. 66, 3331–3346 (2023).

Denmark, S. E., Kornfilt, D. J. P. & Vogler, T. Catalytic asymmetric thiofunctionalization of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 15308–15311 (2011).

Denmark, S. E., Hartmann, E., Kornfilt, D. J. P. & Wang, H. Mechanistic, crystallographic, and computational studies on the catalytic, enantioselective sulfenofunctionalization of alkenes. Nat. Chem. 6, 1056–1064 (2014).

Denmark, S. E. & Chi, H. M. Lewis base catalyzed, enantioselective, intramolecular sulfenoamination of olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8915–8918 (2014).

Roth, A. & Denmark, S. E. Enantioselective, lewis base-catalyzed, intermolecular sulfenoamination of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13767–13771 (2019).

Matviitsuk, A., Panger, J. L. & Denmark, S. E. Enantioselective inter- and intramolecular sulfenofunctionalization of unactivated cyclic and (Z)‑alkenes. ACS. Catal. 12, 7377–7385 (2022).

Liu, X., An, R., Zhang, X., Luo, J. & Zhao, X. Enantioselective trifluoromethylthiolating lactonization catalyzed by an indane based chiral sulfide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 5846–5850 (2016).

Luo, J., Cao, Q., Cao, X. & Zhao, X. Selenide-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of trifluoromethylthiolated tetrahydronaphthalenes by merging desymmetrization and trifluoromethylthiolation. Nat. Commun. 9, 527–536 (2018).

Liu, X., Liang, Y., Ji, J., Luo, J. & Zhao, X. Chiral selenide-catalyzed enantioselective allylic reaction and intermolecular difunctionalization of alkenes: Efficient construction of C-SCF3 stereogenic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4782–4786 (2018).

Liang, Y. & Zhao, X. Enantioselective construction of chiral sulfides via catalytic electrophilic azidothiolation and oxythiolation of N-allyl sulfonamides. ACS Catal. 9, 6896–6902 (2019).

Xie, Y.-Y. et al. Lewis Base/BrønstedAcid co-catalyzed enantioselective sulfenylation/semipinacol rearrangement of Di- and trisubstituted allylic alcohols. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 58, 12491–12496 (2019).

Liu, X.-D. et al. Chiral sulfide/phosphoric acid cocatalyzed enantioselective intermolecular oxysulfenylation of alkenes with phenol and alcohol O-nucleophiles. CCS Chem. 4, 3342–3354 (2022).

Liu, X.-D., Ye, A.-H. & Chen, Z.-M. Catalytic enantioselective intermolecular three-component sulfenylative difunctionalizations of 1,3-dienes. ACS Catal. 13, 2715–2722 (2023).

Guan, H., Wang, H., Huang, D. & Shi, Y. Enantioselective oxysulfenylation and oxyselenenylation of olefins catalyzed by chiral Brønsted acids. Tetrahedron 68, 2728–2735 (2012).

Li, L., Li, Z., Huang, D., Wang, H. & Shi, Y. Chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed enantioselective sulfamination of amino-alkenes. RSC Adv. 3, 4523–4525 (2013).

Wang, J.-J., Yang, H., Gou, B.-B., Zhou, L. & Chen, J. Enantioselective organocatalytic sulfenylation of β‑naphthols. J. Org. Chem. 83, 4730–4738 (2018).

Kesavan, A. & Anbarasan, P. Catalytic enantioselective oxysulfenylation of o-vinylanilides. Chem. Commun. 58, 282–285 (2021).

Luo, H.-Y. et al. Chiral selenide/achiral sulfonic acid cocatalyzed atroposelective sulfenylation of biaryl phenols via a desymmetrization/kinetic resolution sequence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2943–2952 (2022).

Zhu, D., Yu, L., Luo, H.-Y., Xue, X.-S. & Chen, Z.-M. Atroposelective electrophilic sulfenylation of N-Aryl aminoquinone derivatives catalyzed by chiral SPINOL-derived sulfide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 61, e202211782 (2022).

Zhang, X.-Y., Zhu, D., Huo, Y.-X., Chen, L.-L. & Chen, Z.-M. Atroposelective sulfenylation of biaryl anilines catalyzed by chiral SPINOL-derived selenide. Org. Lett. 25, 3445–3450 (2023).

Zhu, D. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of planar-chiral sulfur-containing cyclophanes by chiral sulfide catalyzed electrophilic sulfenylation of arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318625 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. Chiral Lewis Base/achiral acid co-catalyzed atroposelective sulfenylation of pyrrole derivatives: Construction of C-N axially chiral sulfides. Chin. J. Chem. 42, 2005–2009 (2024).

Böhmer, V., Kraft, D. & Tabatabai, M. Inherently chiral calixarenes. J. Incl. Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem. 19, 17–39 (1994).

Dalla Cort, A., Mandolini, L., Pasquini, C. & Schiaffino, L. “Inherent chirality” and curvature. New. J. Chem. 28, 1198–1199 (2004).

Szumna, A. Inherently chiral concave molecules from synthesis to application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 4274–4285 (2010).

Zhou, H., Ao, Y.-F., Wang, D.-X. & Wang, Q.-Q. Inherently chiral cages via hierarchical desymmetrization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 16767–16772 (2022).

Luo, J., Zheng, Q., Chen, C. & Huang, Z. T. Progress in inherently chiral calixarenes. Prog. Chem. 18, 897–906 (2006).

Durmaz, M., Alpaydin, S., Sirit, A. & Yilmaz, M. Enantiomeric recognition of amino acid derivatives by chiral schiff bases of calix[4]arene. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 18, 900–905 (2007).

Shirakawa, S., Kimura, T., Murata, S. I. & Shimizu, S. Synthesis and resolution of a multifunctional inherently chiral calix[4]arene with an ABCD substitution pattern at the wide rim: the effect of a multifunctional structure in the organocatalyst on enantioselectivity in asymmetric reactions. J. Org. Chem. 74, 1288–1296 (2009).

Li, S.-Y., Xu, Y.-W., Liu, J.-M. & Su, C.-Y. Inherently chiral calixarenes: Synthesis, optical resolution, chiral recognition and asymmetric catalysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 429–455 (2011).

Nandi, P., Solovyov, A., Okrut, A. & Katz, A. AlIII-calix[4]arene catalysts for asymmetric Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction. ACS Catal. 4, 2492–2495 (2014).

Cao, Y.-D. et al. Preparation of both antipodes of enantiopure inherently chiral calix[4]crowns. J. Org. Chem. 69, 206–208 (2004).

Luo, J., Zheng, Q.-Y., Chen, C.-F. & Huang, Z.-T. Synthesis and optical resolution of a series of inherently chiral calix[4]crowns with cone and partial cone conformations. Chem. Eur. J. 11, 5917–5928 (2005).

Shirakawa, S., Moriyama, A. & Shimizu, S. Design of a novel inherently chiral calix[4]arene for chiral molecular recognition. Org. Lett. 9, 3117–3119 (2007).

Barton, O. G., Neumann, B., Stammler, H.-G. & Mattay, J. Intramolecular direct arylation in an A, C-functionalized calix[4]arene. Org. Biomol. Chem. 6, 104–111 (2008).

Holub, J., Eigner, V., Vrzal, L., Dvořáková, H. & Lhoták, P. Calix[4]arenes with intramolecularly bridged meta positions prepared via Pd-catalysed double C-H activation. Chem. Commun. 49, 2798–2800 (2013).

An, F.-J. et al. Bridging chiral calix[4]arenes: description, optical resolution, and absolute configuration determination. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 5, 1012–1016 (2016).

Arnott, G. E. Inherently chiral calixarenes: Synthesis and applications. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 1744–1754 (2018).

Hodson, L. et al. Facile synthesis of a C4-symmetrical inherently chiral calix[4]arene. Chem. Commun. 57, 11045–11048 (2021).

Lhoták, P. Direct meta substitution of calix[4]arenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 220, 7377–7390 (2022).

Tang, M. & Yang, X. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral molecules: Recent advances. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 26, e202300738 (2023).

Browne, J. K., McKervey, M. A., Pitarch, M., Russell, J. A. & Millership, J. S. Enzymatic synthesis of nonracemic inherently chiral calix[4]arenes by lipase-catalysed transesterification. Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 1787–1790 (1998).

Shibashi, K., Tsue, H., Takahashi, H. & Tamura, R. Azacalix[4]arene tetramethyl ether with inherent chirality generated by substitution on the nitrogen bridges. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 20, 375–380 (2009).

Tong, S. et al. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis and switchable chiroptical property of inherently chiral macrocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14432–14436 (2020).

Li, X.-C., Cheng, Y., Wang, X.-D., Tong, S. & Wang, M.-X. De novo synthesis of inherently chiral heteracalix[4] aromatics from enantioselective macrocyclization enabled by chiral phosphoric acid-catalyzed intramolecular SNAr reaction. Chem. Sci. 15, 3610–3615 (2024).

Lu, Q.-L., Wang, D.-X., Tong, S., Zhu, J. & Wang, M.-X. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral macrocycles by dynamic kinetic resolution. ACS Catal. 14, 5140–5146 (2024).

Zhang, Y.-Z., Xu, M.-M., Si, X.-G., Hou, J.-L. & Cai, Q. Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via palladium-catalyzed asymmetric intramolecular C−H arylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22858–22864 (2022).

Zhang, X., Tong, S., Zhu, J. & Wang, M.-X. Inherently chiral calixarenes by a catalytic enantioselective desymmetrizing cross dehydrogenative coupling. Chem. Sci. 14, 827–832 (2023).

During the preparation of our work, Liu group reported the enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via CPA-catalyzed three-component Povarov reaction. Jiang, Y.-K., Tian, Y.-L., Feng, J., Zhang, H., Wang, L., Yang, W.-A., Xu, X.-D. & Liu, R.-R. Organocatalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Inherently Chiral Calix[4]arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407752 (2024).

During the preparation of our work, Yang group reported the enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via CPA-catalyzed three-component Povarov reaction. Yu, S., Yuan, M., Xie, W., Ye, Z., Qin, T., Yu, N. & Yang, X. Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Inherently Chiral Calix[4]arenes via Sequential Povarov Reaction and Aromatizations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202410628 (2024).

Neel, A. J., Hilton, M. J., Sigman, M. S. & Toste, F. D. Exploiting non-covalent π interactions for catalyst design. Nature 543, 637–646 (2017).

Chen, Z.-M., Hilton, M. J. & Sigman, M. S. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective redox-relay heck arylation of 1,1-disubstituted homoallylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11461–11464 (2016).

Tao, Z., Robb, K. A., Zhao, K. & Denmark, S. E. Enantioselective, Lewis base-catalyzed sulfenocyclization of polyenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3569–3573 (2018).

Li, T.-Z. et al. Regio-and enantioselective (3+3) cycloaddition of nitrones with 2-indolylmethanols enabled by cooperative organocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2355–2363 (2021).

Cai, S. et al. Formaldehyde-mediated hydride liberation of alkylamines for intermolecular reactions in hexafluoroisopropanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5952–5963 (2024).

Motiwala, H. F. et al. HFIP in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 122, 12544–12747 (2022).

Colomer, I., Chamberlain, A. E. R., Haughey, M. B. & Donohoe, T. J. Hexafluoroisopropanol as a highly versatile solvent. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0088 (2017).

Anh To, T., Pei, C., Koenigs, R. M. & Vinh Nguyen, T. Hydrogen bonding networks enable Brøsted acid-catalyzed carbonyl-olefin metathesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202117366 (2022).

Anh To, T., Phan, N. T. A., Mai, B. K. & Vinh Nguyen, T. Controlling the regioselectivity ofthe bromolactonization reaction in HFIP. Chem. Sci. 15, 7187–7197 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank National Natural Science Foundation of China (22471158 and 22071149, Z.-M. C.), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (23ZR1428200, Z.-M. C.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YG2024QNB27, Z.-M. C.), and 2022 ChiFeng Regional Collaborative Innovation Platform Technology Cooperation Project (2022sj002, T.-M. D.) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-M. C. and X.-Y. Z. conceived and designed the project. X.-Y. Z. and D. Z. contributed equally to this work. X.-Y. Z., D. Z., R.-F. C., Y.-X. H., and T.-M. D. performed the experiments. Z.-M. C., X.-Y. Z., and D. Z. prepared the manuscript and supporting information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shuo Tong and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, XY., Zhu, D., Cao, RF. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral sulfur-containing calix[4]arenes via chiral sulfide catalyzed desymmetrizing aromatic sulfenylation. Nat Commun 15, 9929 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54380-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54380-1

This article is cited by

-

Desymmetric esterification catalysed by bifunctional chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes provides access to inherently chiral calix[4]arenes

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via organocatalyzed aromatic amination enabled desymmetrization

Nature Communications (2025)