Abstract

Self-promotion in science is ubiquitous but may not be exercised equally by everyone. Research on self-promotion in other domains suggests that, partly due to adverse reactions to non-gender-conforming career-enhancing behaviors, women tend to self-promote less often than men. We test whether this pattern extends to online spaces by examining scholarly self-promotion over six years using 23M tweets about 2.8M research papers authored by 3.5M scientists. We find that, overall, women are about 28% less likely than men to self-promote their papers on Twitter (now X) despite accounting for important confounds. The differential adoption of Twitter does not fully explain the gender gap in self-promotion, which is large even in relatively gender-balanced research areas, where adversity is expected to be smaller. Moreover, we find that the gender gap increases with higher performance and academic status, being most pronounced for research-prolific women from top-ranked institutions who publish papers in high-impact journals. We also find differential returns with respect to gender: while self-promotion is associated with increased tweets of papers compared to no self-promotion, the increase is slightly smaller for women than for men. Our findings reveal that scholarly self-promotion online varies meaningfully by gender and can contribute to a measurable gender gap in the visibility of scientific ideas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional and social media play an important role in the dissemination of scientific findings1,2. Scholars across disciplines commonly use social media platforms like Twitter/X to discuss ideas, learn, and promote their work1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Despite the evolving debate on the link between online attention and academic citations11,12,13,14, recent evidence from studies with correlational and causal designs suggests that the online visibility of scientific papers amplifies their impact in the academy through citations15,16,17,18,19,20. Higher online visibility may also promote diffusion beyond the academy21,22, bringing more consequential outcomes and impact through media coverage and policy take-up23,24,25, which further contributes to prevalent alternative measures for scholarly evaluation26,27,28.

However, the online visibility of scholars’ work is not equally distributed across genders. Recent research reveals that gender gaps observed in traditional scientific outcomes such as citations and awards29,30,31 also appear in online visibility32,33, despite the absence of traditional gate-keepers. Closing this gender gap requires understanding the social and cultural factors involved in online platforms that may differentially impact who can engage effectively in promoting their scientific achievements. Academic self-promotion, which involves speaking directly about one’s strengths and achievements as a career-enhancing practice34,35, is an early mechanism that could contribute to substantial differences in online visibility8,10,36,37.

Studying the gender gaps in self-promotion is thus important for understanding women’s potential underrepresentation and lack of inclusion in science-related conversations. Raising awareness of such gender gaps is a prerequisite for improving research policy through properly accounting for biases that appear in the public’s opinion about who is driving scientific progress and innovation23, which can affect young people’s career choices38 and shape career-critical promotion decisions in academia39. More broadly, informing people about gender gaps in self-promotion can affect their subsequent opinions and behavior38,39,40,41 and contribute to targeted interventions that promote gender equity in science42,43,44.

Several lines of literature suggest that many professional contexts are more conducive to self-promotion by men than women. First, one must decide which of their achievements are worthy of promotion. A number of studies find differences in self-assessment, with women often undervaluing their performance in stereotypically male-dominated domains, including science and business, and men overvaluing theirs45,46,47,48. For example, a recent study by Exley and Kessler shows that men and boys self-assess the same performance on math tasks much higher than women and girls, and the gap arises as early as sixth grade49. Such overvaluation, alongside misaligned incentives in science, can encourage exaggeration in scientific reporting at the expense of accuracy and retractions24,50. The second literature concerns the “backlash effect,” whereby audiences differentially penalize women for self-promotion because it is incongruent with stereotypes of modesty and pro-sociality51,52,53,54,55,56. Supporting this view on double standards, empirical research across many settings finds that women who self-promote are often seen as more arrogant and less likable than self-promoting men57,58,59,60,61,62. Third, self-promotion takes time. A growing literature finds that men spend less time than women on non-promotable tasks that are crucial to the sustainability of the academic ecosystem, such as emotional support towards trainees63,64 and academic services65. Thus gender differences in time allocated to key non-promotable work vs. research activities may give men more bandwidth to self-promote.

At the same time, women may now engage more in self-promotion as a result of their increased awareness of gender gaps and dedicated efforts to counter them66,67. For example, recent research on labor economics shows that women negotiate pay at least as much as men, indicating a closing of the gender gap in speaking up for oneself in professional contexts, albeit one that has yet to translate to the closing of the pay gap itself 68,69.

Adding to this debate, online spaces introduce inherent uncertainties about social behavior70. Theoretically, online environments should feature less barriers for women than conventional offline settings71,72. However, some social media platforms such as Twitter promote self-importance, combative behavior, and masculinity73. This may create a misalignment between cultural norms on Twitter and societal expectations of women’s behavior, which can further nurture a more unwelcoming climate for women, impacting their willingness to self-promote. Additionally, studies of online harassment, even in non-self-promotional contexts, find gender differences in how frequently harassment occurs. By one estimate, 85% of women globally have experienced some form of online harassment and abuse74. Harassment is common on social media sites, with 61% of women considering it a major problem75, and may naturally discourage posting. Recent research documents how gender harassment has changed the way women popularize science76.

These contrasting possibilities laid out in the literature motivate our first research question: Is there a gender gap in scholarly self-promotion on social media? Additionally, we explore whether the gap has changed over time and whether it appears in all areas of science, including those with better gender representation, where self-assessment may be more gender equal.

Informing interventions to close a potential gender gap in self-promotion requires understanding the nuances of who is more likely to engage in self-promotion. On the one hand, self-assessment biases are likely to be smaller for prominent individuals and/or when the performance is more unambiguously outstanding49. On the other hand, past research shows that accomplished women leaders can elicit more pushback for their success77, for instance, experiencing less positive sentiment in their media coverage56. The net effect of high status and better performance on the gender gap in self-promotion is thus ambiguous. We ask: How does the gender gap vary with the academic status of the scholar and the performance of their work? Lastly, self-promotion is a strategic action that likely depends on expected returns, such as gains in visibility from self-promotion. If expected returns vary by gender, scholars will likely engage in it differently. Accordingly, we ask: Is there a gender gap in the returns for self-promotion?

We explore our research questions by combining two large-scale bibliographic datasets – the Altmetric database of papers’ online mentions and the Microsoft Academic Graph (MAG) database that contains metadata about papers and their authors such as publication venues, affiliations, productivity metrics, and research fields78,79,80 (See details in Methods and Supplementary Note A). Altmetric is the most comprehensive database to date for monitoring online posts about research papers. It covers about 27% of all research papers indexed in the MAG database during our study period. Altmetric’s coverage favors more prominent papers that have received some online attention23,81. We link the two datasets based on the Document Object Identifier (DOI).

This data combination process provides us with a multi-disciplinary dataset of 2,834,829 research papers published between 2013 and 2018 by 3,503,674 unique authors. These papers have received at least some mentions on online platforms as tracked by Altmetric.com82. Our self-promotion and online visibility measures focus on Twitter/X. During the time frame studied here, Twitter was the most commonly used platform for online science dissemination, accounting for 92% of all paper mentions on major social media platforms24. In our sample, 72.2% of papers have received at least one mention on Twitter.

Because authors might promote some of their papers but not others, and not all authors of a paper are equally likely to promote it, our unit of analysis is the (paper, author) pair. We identify 11,396,752 (paper, author) pairs, each of which is a candidate for self-promotion (Fig. 1). This design enables us to isolate the role of gender because we can account for differences in papers and authors that are associated with self-promotion. For example, the same author may consider some topics or publications as more worthy of self-promotion than others, and different authors of the same paper may base individual self-promotion decisions on their authorship roles.

A paper can have multiple authors, and it can receive several mentions from different Twitter users, including academic authors and non-academics. We treat each (paper, author) pair, or each authorship shown in this diagram, as the unit of analysis, and accordingly code whether the author is active on Twitter at the publication time of the paper (the Button icon). In this illustration, Person 1, who is active on Twitter at the time of Paper A's publication, self-promotes. Neither of his co-authors, Person 2 or 3, is active on Twitter and therefore do not self-promote. By the time Paper B is published, Person 2 is active on Twitter and mentions the paper, although she is not one of its authors. Out of Paper B's authors, Person 4 self-promotes, but Person 3 does not, despite that he now become active on Twitter. Paper B is also mentioned by others who are not academics (not shown in this illustration). Among scholarly authors, we distinguish women and men to investigate the likelihood of self-promotion for each (paper, author) pair. Furthermore, for each paper, we record the total number of mentions on Twitter, which we use to examine potential gains in visibility associated with self-promotion. This illustration has been designed using resources from Flaticon.com that are free for personal and commercial purposes with attribution. Person icons created by Trazobanana; Vision icons created by Afif Fudin; Paper icons created by Freepik; On/Off button icons created by Those Icons.

By quantifying the self-promotion gap over six years among major academic fields, we provide a systematic examination of a plausible mechanism behind the lower visibility of women’s scientific achievements on social media. Our study reveals a sizeable gender gap that appears in all academic fields and is more pronounced for research-prolific women from top-ranked institutions who publish papers in high-impact journals. Complemented by our finding that women’s self-promotion is associated with slightly lower returns in terms of social media mentions, our work highlights the need to think of alternative strategies for equitably promoting and evaluating scholarly work. Through revealing the gender gap, which may be unknown to scientists and academic decision-makers, our study can stimulate further research on gender inequity in academia and may contribute to gender balance in other important scientific outcomes. We discuss practical implications of our research on designing effective policies and interventions for closing the gender gap in visibility and academic careers.

Results

The increasing gender gap in self-promotion

Figure 2 A shows the predicted self-promotion probability by year for men and women (N = 11,396,752; see coefficients in Table 1 and raw gender differences in our data in Supplementary Fig. S1, S2). Our model predicts that, from 2013 to 2018, male authors had a chance of self-promoting their papers between 2.46% (95% CI = [2.42%, 2.50%]) and 10.55% (95% CI = [10.45%, 10.66%]), while comparable female authors’ self-promotion chance was between 1.75% (95% CI = [1.72%, 1.78%]) and 7.69% (95% CI = [7.60%, 7.77%]), which is about 28% lower on average. This disparity exists even among female and male authors of the same paper (p < 0.001; Model 5 in Table 1).

A, Predicted probability of self-promotion by gender based on a mixed-effects logistic regression model (Table 1) fitted to all 11,396,752 (paper, author) pairs where the dependent variable is coded as 1 if the author has self-promoted the paper. B Same as A, but for the predicted probability of active presence on Twitter by gender, based on a regression model with the same set of controls (Table 2). The dependent variable is coded as 1 if the author is active on Twitter at the paper’s publication date. C Predicted probability of self-promotion for the subset of 618,742 (paper, author) pairs where the author is active on Twitter (Table 3). All three regression models have the same set of controls, including publication year, journal impact factor, authorship position, number of authors, affiliation rank and ___location, author productivity and number of citations, research topics, and paper random effects. Control variables have been set to their median values to create these plots. Error bars indicate 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Figure 2 A also shows that, while both genders self-promote more often over time (p < 0.001 for year coefficients in Table 1), the gender gap has been growing from 2013 to 2018. This suggests that the culture around self-promotion may have been changing, and it is an activity considered more and more important by scholars. The difference does not disappear when measuring self-promotion using only original tweets or retweets (p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that the gap exists even in the arguably less direct form of self-promotion.

Since the gender gap in self-promotion could be impacted by potential biases in gender inference or group dynamics within mixed-gender teams, we perform several robustness checks. The gender gap is remarkably consistent when (1) including author names classified as gender-neutral as a separate category (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S4), (2) excluding author names associated with East Asian ethnicities that usually do not encode a clear gender signal (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S5), (3) considering self-promotion as being the first person among the authors who tweet about the paper (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S6), and (4) subsetting the data to solo-authored papers only (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S7).

These additional analyses show that authors with gender-neutral names self-promote less often than those with gender-distinct names, the gender gap remains after excluding East Asian ethnicities, and potential role assignments do not drive the self-promotion gap in mixed-gender teams. Furthermore, we use propensity score matching to reduce the confounding effects that may be unaccounted for by the regression model. We still find that women self-promote their research less often than comparable men (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S8-S9). As a final test, we show that the result is consistent when restricting the analysis to observations with the same authorship position in the same research area, such as last authors in Natural Sciences, and first authors in Social Sciences (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S22).

The gender gap is not explained entirely by gender differences in Twitter adoption

In our previous analysis, we do not distinguish between authors who do not self-promote because they are not active on Twitter and those who are active but choose not to post about their papers. However, women’s lower self-promotion on Twitter may be produced by their choices conditional on being active on academic Twitter, or simply adopting Twitter at lower rates83,84.

To explore the latter possibility, we first run a regression model with the same specification as for predicting self-promotion but changing the dependent variable to whether the author is active on Twitter at the time of the paper’s publication. Figure 2B shows that among all authors, men are indeed more likely than comparable women to be active on Twitter (p < 0.001; see regression coefficient in Table 2). Running the same regression model from Fig. 2A on the subset of (paper, author) pairs where the author was active on Twitter at the time of publication shows a considerably higher level of self-promotion among Twitter-active authors than among all authors (Fig. 2C vs. Fig. 2A). Yet, even in this subset, Fig. 2C shows that women self-promote about 9.4% less than men on average (p < 0.001; see regression coefficient in Table 3), suggesting that the substantial gender gap is not fully explained by differences in active use of Twitter.

The gap is robust to variation in a research area’s gender representation

Does a higher representation of women in a given research area decrease the gender gap in self-promotion? To answer this question, we estimate the overall gender gap in self-promotion across the four broad research areas of social, life, health, and physical sciences. Specifically, we fit a separate regression model used in Fig. 2A for each broad area. In our dataset, the authorship share of women for papers from these four broad areas is 46%, 43%, 44%, and 28%, respectively.

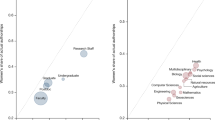

Figure 3 A shows the predicted self-promotion probability, which is higher for men than for women in all four broad areas (p < 0.001; see regression coefficients in Supplementary Table S10). Social scientists are, on average, about three times as likely to promote their research as scientists in the other three areas (Fig. 3A). Yet, the gender gap is comparable across research areas regardless of gender balance. Even in physical sciences, where only approximately 1 in 4 authors are women, the gap is comparable to the gap in broad areas that are approaching parity in authorship in our data. The results are consistent when fitting the regression to the subset of Twitter-active observations in each broad area (Supplementary Table S11). Furthermore, the gender gap is universally observed in subfields based on 26 Scopus Subject Areas (p < 0.001 for 23 areas; Supplementary Table S23). This suggests that the gender gap in self-promotion is consistently large, even in the presence of substantial variation in an area’s gender representation85.

A, The predicted gender gap in self-promotion is of similar magnitude across all four broad research areas. We fit a separate model for each broad area while still controlling for fine-grained subject areas (N = 804,121; 4,123,459; 4,952,083; 2,561,568 for Social, Life, Health, and Physical Sciences; Supplementary Table 10). B–D The likelihood of self-promotion as a function of journal impact factor, author productivity, and affiliation rank, predicted based on our most comprehensive model that also adds an interaction term between gender and the corresponding variable (Supplementary Table 12–14). To quantify research productivity, we decile author’s number of publications as a measure of their productivity (C, a larger bin indicates a more productive decile). Similarly, we decile author’s affiliation rank (D, a larger bin indicates a higher rank decile). The three regressions in B–D are fitted to all 11,396,752 (paper, author) pairs. Predictions are based on setting all control variables at their median values in our data. Error bars indicate 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

The gender gap is larger for prolific women publishing in high-impact journals

To examine the association between self-promotion gender gap and academic performance, we fit the same regression model used in Fig. 2A by including an interaction term between gender and the paper’s journal impact factor, a widely used scholarly performance measure. We then predict the self-promotion rates across different levels of journal impact factor for both genders in Fig. 3B. As expected, the probability of self-promotion is positively associated with journal impact factor (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S12). However, the gender gap is larger for higher impact factor journals as shown in Fig. 3B (p < 0.001 for the interaction term in Supplementary Table S12). In particular, for papers published in journals with an impact factor above 40, men (0.165; 95% CI = [0.162, 0.168]) are about 85% more likely to self-promote than women (0.089; 95% CI = [0.087, 0.091]). However, for papers published in lower-tier journals (impact factor below 5), the predicted self-promotion probability for men (0.044; 95% CI = [0.043, 0.045]) is only 30% higher than for women (0.034; 95% CI = [0.034, 0.034]).

To investigate the effect of academic status, we focus on the author’s academic standing as quantified by (i) research productivity and (ii) affiliation rank. We again fit the same regression model used in Fig. 2A by including an interaction term between gender and the author’s number of publications or the author’s affiliation rank. We first show in Fig. 3C the predicted self-promotion probability as a function of the author’s number of publications, which is an established measure of productivity. We find that, regardless of gender, a scholar’s self-promotion probability increases as their productivity grows and then saturates with research experience in the mid-to-late career stage (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S13). This finding is consistent when measuring career stage or productivity as the number of years since the author’s first publication (p < 0.001; see predictions in Supplementary Fig. S4). One possible explanation is that junior scholars spend most of their time conducting research to build a portfolio, while the task of marketing is often taken on by more experienced scholars in the research team86,87. However, this transitional change does not apply equally to men and women. Figure 3C shows a larger disparity among more experienced scholars: the predicted gender difference in self-promotion probability is almost doubled for authors in the most vs. the least prolific group (p < 0.001 for the interaction term in Supplementary Table S13).

We show in Fig. 3D the predicted self-promotion probability for authors from different affiliation ranks, which is another proxy for the author’s academic status. We find that authors from the highest-rank decile group are much more likely to self-promote their papers than those from the lowest-rank group (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S14), which is not unexpected. However, as with research productivity, Fig. 3D shows that the gender gap is larger for authors from more prominent affiliations (p = 0.02 for the interaction term in Supplementary Table S14).

These results suggest that there are universal and well-defined self-promotion patterns, which are associated with academic performance (journal impact factor) and status (research productivity and affiliation rank). However, scholar’s self-promotion changes with different intensities in response to these mediating factors, resulting in an even larger gender gap at the high end of the spectrum. This evidence points to the potential role of pushback against accomplished female scientists and calls for more investigations to establish a causal relationship.

Differential return on self-promotion

A closing piece in our longitudinal investigation of scholarly self-promotion examines the visibility gains from promoting one’s own paper on social media and tests whether it differs by gender. Instead of measuring the return as direct engagement with self-promotional tweets, such as the number of retweets or likes, our measure of return compares the paper’s total number of tweet mentions in two conditions: with self-promotion and without self-promotion. This design allows us to account for gender differences that may already occur without self-promotion and takes into account the contribution of other forms of promotion to the total number of mentions. For example, some scholars may receive more mentions in the mainstream media than others, even without self-promoting their papers.

We use a negative binomial regression88 to predict a paper’s total number of tweet mentions by including an interaction term between author gender and self-promotion (see details in Methods). We focus this analysis on the subset of observations where the author was active on Twitter when the paper was published (N = 618,742). This enables us to control for the author’s log-scaled number of followers on Twitter in addition to the controls defined previously.

As expected, Fig. 4 shows that self-promotion is strongly associated with a paper’s total number of tweet mentions (p < 0.001 in Table 4). Moreover, papers tend to receive more and more tweet mentions over our studied time period (p < 0.001 for year coefficients in Table 4), suggesting the growing online attention to scientific papers. Importantly, however, women’s self-promotion is associated with fewer boost in mentions than men’s (p < 0.001 for the interaction term in Table 4).

This plot shows the marginal effect of self-promotion (vs. no self-promotion) for both genders by year, based on a negative binomial regression fitted to 618,742 (paper, author) pairs where the author is active on Twitter at the paper’s publication time (Table 4). The model additionally controls for author’s follower count (log-scaled) and adds an interaction term between gender and self-promotion status (binary). Predictions are based on setting all control variables at their median values in the data. Error bars indicate 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

To check the robustness of this finding, we run four additional tests and examine the interaction term between gender and self-promotion. First, we confirm that the result is consistent when fitting a separate model for papers published in each year (p = 0.039 for 2014 and p < 0.001 for all other years; Supplementary Table S16). Second, to isolate the gender effect, we eliminate potential self-promotion dynamics in mixed-gender teams by fitting a separate model for the small subset of solo-authored papers. We find that the results are less statistically significant but qualitatively similar (p = 0.181; Supplementary Table S17), possibly due to a small number of observations (N = 20,216). Third, we demonstrate that the finding is robust when defining self-promotion as sharing the paper on social media within one day of publication (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S18). This additional analysis shows that the gender difference in return equally applies to early self-promotion, indicating that it is unlikely that women’s self-promotion is ineffective because they do not do it in a timely manner. Fourth, the result also holds when we consider mentions of the paper by only scientists or non-scientists (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S19, S20), indicating that neither of these groups alone can account for the gender difference in return on self-promotion.

Discussion

Based on the analysis of 3,503,674 authors and their 2,834,829 research papers published between 2013 and 2018 across four broad fields of scholarship, we find a large gender gap in self-promotion on Twitter. Women are, on average, 28% less likely than men to self-promote their papers even after taking into account important confounding factors such as the year of publication, fine-grained research fields, as well as author- and paper-level characteristics related to status and performance. The gap even appears when comparing authors of the same paper, and is robust to the same authorship position in the same field. The gender gap appears to have increased from 2013 to 2018.

We also find that differential adoption of Twitter does not explain the full gender gap: while our results show that female scholars are slightly underrepresented on Twitter relative to males, the gender gap in self-promotion also appears among those active on Twitter. This is surprising as women who are active on Twitter already show some interest in online visibility. Our finding thus suggests that even for women who are interested in an inherently self-promotional platform, the gender gap still exists.

The gender gap in self-promotion is consistent with gender differences in the tendency for embellished presentation of results89,90 and invites interesting connections with the practice of self-citation. The gendered nature of self-citation is contested in the literature. Some large-scale bibliometric studies argue that women self-cite less than men30,91,92, whereas others dispute this result and find no gender differences93,94. One possible interpretation of the difference between the gender gap documented in our study and the less robust one in self-citation is that the latter is a subtle, “quiet” way to self-promote in academia. In comparison, sharing one’s research on social media could be considered a “loud” form of self-promotion. Because of anticipated backlash in online spaces, women may be more comfortable with the “quiet” form but continue to shy away from the “loud” way of self-promotion. Overall, the relationship between self-citation, self-marketing on social media, and other types of self-promotion (e.g., mailing out published articles to colleagues) presents exciting questions that deserve further investigation.

Examining factors that can moderate the size of the gender gap in online self-promotion, we find that it is not substantially smaller in more gender-balanced fields. This suggests that improved gender representation is unlikely to fix the self-promotion gap in the short term. Importantly, we also find that factors associated with academic performance and status can substantially moderate the size of the gender gap. In particular, the gap in self-promotion grows for papers published in higher-impact journals and when authors are more productive and come from higher-ranked institutions. These results suggest that women’s concerns about pushback in response to their self-promotion may dominate the likely high self-assessment associated with being an established scholar and assurance that the contribution is worth promoting31,56. When accomplished women self-promote less than comparable men in the scientific workforce characterized by a leaky pipeline with fewer and fewer women in higher ranks, women’s visibility will remain low.

In line with recent work33, we also find a gender gap in the visibility returns associated with self-promotion. Although self-promotion is statistically linked to higher mentions for both genders, the increase is slightly smaller for women than for men. This association may be produced by various mechanisms, such as different language styles used by men and women89, or the unobserved network effects from offline contexts95. As an initial exploration, our linguistic analysis of self-promotional tweets shows that men use more promotional words90,96 such as “novel,” “excellent,” “robust,” “remarkable,” and “unprecedented” than women, while women use more supportive words such as “amazing,” “supportive,” and “inspiring” when promoting their research (Supplementary Fig. S5, S6). Overall, our observational study provides an empirical documentation of a measurable gender gap in online self-promotion across all areas of science.

Our study is not without limitations. First, we investigate a single social media platform. Although Twitter/X is the largest platform based on mentions of scientific papers, it would be interesting to extend the investigation to other social media sites. Second, we use name-inferred gender as a proxy of the author’s true gender identity. Our two validations show that, overall, there is a high degree of agreement between the predicted and self-reported or manually verified genders. However, the dataset of physists used in our validation is not gender-balanced, as only 18.9% of the authors self-reported to be women. Thus, the accuracy of gender labeling may be lower than reported. Relatedly, our validation result is more applicable to Western names because many East Asian names do not have a distinctively predicted gender label and are thus excluded from our evaluation23,97. Third, most authors in our data come from Western countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany (these three countries alone account for 49% of observations), and authors affiliated with these countries are much more likely to be active on Twitter than those from East Asian countries such as China. Thus, our finding is more representative of institutions in Western countries where Twitter is commonly used.

Fourth, our study does not analyze race/ethnicity and their intersectionality with gender in self-promotion. However, the observed gender gap in self-promotion is likely to vary between different races and ethnicities. The literature shows that intersectional categories develop bias in self-assessment regardless of actual performance98, have a heightened sensitivity to unprofessional feedback99, and receive worse treatment and fewer rewards100,101. Indeed, we find that including authors with gender-neutral names in the analysis shows that these scholars are the least likely to self-promote. Since authors from certain countries such as China are more likely to have gender-neutral names97,102, the lower self-promotion rate of authors with gender-neutral names may be driven by racially and ethnically differentiated cultural norms around self-marketing on social media. For example, regardless of gender, self-promotion may be considered more acceptable in Western than East Asian cultures103. Addressing this issue around race and ethnicity would be difficult due to challenges in the algorithmic categorization of these categories23,97. We thus view our focus on gender as a contribution to understanding one form of disparity in scholarly recognition and visibility. Further work may investigate intersectionality in self-promotion and examine the specific challenges that underrepresented groups face in self-promotional contexts. Another related limitation of our analysis is that authors of non-binary gender are not identified, which we hope future work can rectify.

Fifth, our study requires matching authors with Twitter users to detect self-promotion. We address this problem using a name-based matching algorithm. Although our validation shows that the matching achieves high accuracy, the algorithm is not perfect. For instance, if women are more likely to use pseudonyms on Twitter, our method would underestimate their actual rate of self-promotion. Yet, these women’s careers would benefit less from self-promotion under their non-publishing name. Future work can develop more sophisticated approaches to address this issue. Sixth, we rely on an open dataset of scholars identified on Twitter to detect if they were active on the platform at the publication date of a paper. The external dataset does well on our validation tests, yet it cannot identify all authors who were active on Twitter during the entirety of the six years we investigated. Finally, some control variables in our model are not precisely measured due to the inherent limitations of the Twitter API. For example, the follower count is measured at our data collection time, not at the paper publication date. Similarly, we do not take Twitter usage variables into account in our main analysis because variables such as follower count may not be simply exogenous – they could be caused by self-promotion. Relatedly, while we show that self-promotion is associated with more return in Twitter mentions, it is also possible that the gender gap in return could be related to women’s decision not to self-promote, further increasing the gender gap in self-promotion rate. Future research could try to distangle the complex relationships between Twitter usage, self-promotion, and return on self-promotion.

Despite these limitations, our study offers insights into scholars’ self-promotion on social media, enriching our understanding of the broader gender inequity in scientists’ online visibility and recognition. First, our work informs the way we interpret online visibility metrics and traditional performance indicators shown to correlate with them such as citations15,17,104,105. Lower visibility metrics for women are a systemic issue with complex underpinnings and are contributed at least in part by men’s higher self-promotion rates and the larger returns they receive from it. This may need to be considered when using such metrics in research evaluation. Criteria for hiring, promotion, and tenure thus may need to be adjusted to ensure that more favorable conditions for men’s self-promotion do not disproportionately disadvantage women.

Second, simply informing individuals about the gender gap may affect collective behavior and judgment38,39,40,41. In our case, revealing the barriers to women’s self-promotion can raise awareness of specific challenges that may trickle down to affect their career progression. This awareness can gradually contribute to a cultural shift within the broader scientific community, encouraging more equitable research evaluation. Practically, institutions may consider informing and educating their employees, including staff, faculty, and any selection committees, about the gender gap in self-promotion and its possible downstream effects on other important academic outcomes. Such training programs may also affect, for example, which readings instructors choose for their courses or recommend to their students, which speakers get invited, and who is considered for an award.

Third, scholarly practices and policies aimed at closing the gender gap in visibility could rely on interventions that aim to “fix the institutions” not “fix the women” by placing additional burdens on them69, especially given that women’s self-promotion is not as effective as men’s. Our work highlights that online platforms are likely to perpetuate existing hierarchies within the academy through self-promotion. Democratizing how papers are shared and made visible demands a collective effort. One possibility is that institutions proactively support the promotion of research outputs through equity-minded press offices. Relatedly, professional organizations can launch initiatives to increase the visibility of female scientists and their work by highlighting their achievements in newsletters, websites, and social media, as well as nominating them for awards and speaking opportunities. Additionally, researchers of any gender could engage in peer promotion, as this is less likely to trigger backlash36,106. Similarly, participation in mentorship programs that offer promotion and advocacy by senior sponsors may also help107. We also would like to note that these suggested policy interventions need to be tested in practice with regard to their effectiveness in closing the gender gap in visibility.

Finally, our study can encourage future research to examine the mechanisms causing the gender gap in self-promotion. Such investigations would be valuable because algorithms on online platforms may amplify small initial differences in online attention, as produced via differential self-promotion practice, into large disparities in ultimate academic recognition70,108 and conventional markers of scientific excellence15,17,20. Additionally, future work utilizing surveys to gauge perceptions of self-promotion could examine why the gender gap is substantial even in relatively gender-balanced fields and why it is larger when promoting achievements widely considered valuable, such as papers in high-impact-factor journals.

Methods

We disclose that this study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of City University of Hong Kong (HU-STA-00001138) and Northwestern University (STU00211720). The study underwent full review (was not exempt) at both IRBs, which all waived the informed consent requirement regarding our analyses of self-promotion using the data from Altmetric, Twitter, and Microsoft Academic Graph. A retrospective approval (fully reviewed) from the University of Michigan IRB (HUM00194927) was given when the self-reported gender data from the Institute of Physics (IOP) were added in our study, which also waived the informed consent requirement regarding our use of the self-reported gender data.

We infer author’s gender using their first names109 (Supplementary Note B). Out of 3,503,674 unique authors, 58% are inferred to be men and 42% women (consistent result with gender-neutral names included as a separate category in the regression is shown in Supplementary Table S4). We validate our gender inferences in two ways (Supplementary Note B). First, we compare the algorithm’s inferences to an auxiliary dataset containing the self-reported gender of 432,888 physical scientists (Supplementary Note B and Supplementary Table S21). Second, we compare the gender inferences to manually labeled gender of 100 randomly selected authors in our data. These validations reveal that our gender classifier is very accurate with the F1 score close to 0.9 (Supplementary Note B). At the level of (paper, author) pairs in our data, men account for a substantially larger fraction than women (64.7% vs. 35.3%).

Our first set of models investigates gender differences in the likelihood of self-promotion. The outcome variable “self-promoted” is an indicator of whether the author in a (paper, author) pair mentioned the paper on Twitter. To detect whether an author self-promotes a paper, we design and validate a heuristic-based method to match author names to the list of Twitter usernames that have mentioned the paper, achieving an out-of-sample F1 > 0.95 (Supplementary Note C).

For each (paper, author) pair, we estimate whether the author was active (not just having an account) in tweeting academic papers when the paper was published (Fig. 1). While no method can perfectly match all scholars to their Twitter accounts because they can adopt usernames unrelated to their academic author names and provide little or no information on their Twitter profile, we use a validated, state-of-the-art external dataset that achieves high accuracy in this setting84,110 (Supplementary Note D). Based on this external dataset, we estimate that the percentage of authors active on Twitter is 4.6% for women and 5.9% for men.

To account for confounding factors that are likely to affect self-promotion tendency, we use a mixed-effects logit model with plausible covariates, fixed effects for papers and authors, as well as random effects for each paper (Supplementary Note E). The paper-level controls include the publication year, the impact factor of the journal publishing the paper, and the research fields associated with the paper. Author-related factors consist of the number of authors, authorship position, affiliation ___location and rank, and author’s previous publication and citation counts. The random effects specification stipulates that each paper has its own underlying probability of being self-promoted, regardless of other factors. This setup enables us to compare self-promotion by different authors of the same paper. Controlling for these confounding factors, which themselves might be related to gender, means that our models estimate gender’s relatively direct association instead of its overall association with self-promotion. Additionally, we obtained consistent results when using propensity score matching to test the robustness of our findings (Supplementary Note F). This allows us to identify matched pairs that are similar on observed variables except the author’s gender.

Our second set of models examines the “return” on self-promotion in terms of a paper’s overall visibility, compared with the condition without self-promotion (Supplementary Note G). We use a negative binomial regression88 to model a paper’s total number of Tweet mentions as a proxy for its online visibility. The model additionally includes an interaction term between author gender and self-promotion to examine how self-promotion is associated with tweet mentions differently for men and women. The unit of analysis is still each (paper, author) pair so that we can measure visibility premium across different authors and their different papers.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that can be used to reproduce our results are deposited on Figshare111 at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Promotion/21843330. The Altmetric data used in this study are available at https://www.altmetric.com/research-access/. The tweet mentions of research papers were collected using the public Twitter API. The Microsoft Academic Graph database used in this study is available at https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/open-academic-graph/. The journal impact data are available from the Web of Science database. The dataset of self-reported gender by physicists was obtained from administrative data provided by the Institute of Physics (IOP). The data are governed by a data-use agreement and an IRB that prevents us from sharing these personally identifiable data, in addition to IOP Publishing’s privacy policy (https://ioppublishing.org/legal/privacy-cookies-policy/). Interested researchers could contact IOP for data access (email: [email protected]).

Code availability

All data are analysed with customized code in Python 3.8.13 and R 4.2.0 using standard software packages. Our code can be accessed on Github112 at https://github.com/haoopeng/gender_promotion.

References

Editorial. Social media for scientists. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1329 (2018).

Peters, H. P. Gap between science and media revisited: Scientists as public communicators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 14102–14109 (2013).

Darling, E., Shiffman, D., Coté, I. & Drew, J. The role of Twitter in the life cycle of a scientific publication. Ideas Ecol. Evol. 6, 4625 (2013).

Morello, L. We can # it: social media is shaking up how scientists talk about sexism and gender issues. Nature 527, 148–152 (2015).

Gero, K. I., Liu, V., Huang, S., Lee, J. & Chilton, L. B. What makes tweetorials tick: How experts communicate complex topics on Twitter. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 5, 1–26 (2021).

Van Noorden, R. Online collaboration: Scientists and the social network. Nat. N. 512, 126 (2014).

Yammine, S. Going viral: how to boost the spread of coronavirus science on social media. Nature 581, 345–347 (2020).

Docter, H. How scientists are making the most of Reddit. Nature 628, 221 (2024).

Thornton, J. When Finnish researchers took on the Twitter trolls. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03407-4 (2021).

Lee, J.-S. M. How to use Twitter to further your research career. Nature 10. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00535-w (2019).

Haustein, S., Peters, I., Sugimoto, C. R., Thelwall, M. & Larivière, V. Tweeting biomedicine: An analysis of tweets and citations in the biomedical literature. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 65, 656–669 (2014).

Ortega, J. L. To be or not to be on Twitter, and its relationship with the tweeting and citation of research papers. Scientometrics 109, 1353–1364 (2016).

Liu, C. & Huang, M.-H. Exploring the relationships between altmetric counts and citations of papers in different academic fields based on co-occurrence analysis. Scientometrics 127, 4939–4958 (2022).

Dehdarirad, T. Could early tweet counts predict later citation counts? A gender study in life sciences and biomedicine (2014–2016). PLOS ONE 15, e0241723 (2020).

Chan, H. F., Önder, A. S., Schweitzer, S. & Torgler, B. Twitter and citations. Econ. Lett. 231, 111270 (2023).

Liakos, W., Burrall, B. A., Hsu, D. K. & Cohen, P. R. Social media (some) enhances exposure of dermatology articles. Dermatol. Online J. 27 (2021).

Peres, M. F., Braschinsky, M. & May, A. Effect of altmetric score on manuscript citations: A randomized-controlled trial. Cephalalgia 42, 1317–1322 (2022).

Costas, R., Zahedi, Z. & Wouters, P. Do “altmetrics” correlate with citations? Extensive comparison of altmetric indicators with citations from a multidisciplinary perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 66, 2003–2019 (2015).

Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Ryan, J. B., Searles, K. & Shmargad, Y. Using social media to promote academic research: Identifying the benefits of Twitter for sharing academic work. PLOS ONE 15, e0229446 (2020).

Luc, J. G. et al. Does tweeting improve citations? One-year results from the TSSMN prospective randomized trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 111, 296–300 (2021).

Eagleman, D. M. Why public dissemination of science matters: A manifesto. J. Neurosci. 33, 12147–12149 (2013).

Brossard, D. & Scheufele, D. A. Science, new media, and the public. Science 339, 40–41 (2013).

Peng, H., Teplitskiy, M. & Jurgens, D. Author mentions in science news reveal widespread disparities across name-inferred ethnicities. Quant. Sci. Stud. 5, 351–365 (2024).

Peng, H., Romero, D. M. & Horvát, E.-Á. Dynamics of cross-platform attention to retracted papers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2119086119 (2022).

Yin, Y., Gao, J., Jones, B. F. & Wang, D. Coevolution of policy and science during the pandemic. Science 371, 128–130 (2021).

Sugimoto, C. R., Work, S., Larivière, V. & Haustein, S. Scholarly use of social media and altmetrics: A review of the literature. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 68, 2037–2062 (2017).

Kwok, R. Research impact: Altmetrics make their mark. Nature 500, 491–493 (2013).

Sopinka, N. M. et al. Envisioning the scientific paper of the future. Facets 5, 1–16 (2020).

Teich, E. G. et al. Citation inequity and gendered citation practices in contemporary physics. Nat. Phys. 18, 1161–1170 (2022).

Sugimoto, C. R. & Larivière, V. Equity for Women in Science: Dismantling Systemic Barriers to Advancement (Harvard University Press, 2023).

Oliveira, D. F., Ma, Y., Woodruff, T. K. & Uzzi, B. Comparison of National Institutes of Health grant amounts to first-time male and female principal investigators. JAMA 321, 898–900 (2019).

Vásárhelyi, O., Zakhlebin, I., Milojević, S. & Horvát, E. Gender inequities in the online dissemination of scholars’ work. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2102945118 (2021).

Song, Y., Wang, X. & Li, G. Can social media combat gender inequalities in academia? Measuring the prevalence of the Matilda effect in communication. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 29, zmad050 (2024).

Schlenker, B. R.Impression management (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1980).

Leary, M. R. Self-presentation: Impression management and interpersonal behavior (Routledge, 2019).

John, L. K. Savvy self-promotion. Harv. Bus. Rev. 99, 145–148 (2021).

Harseim, T. & Goodey, G. How do researchers use social media and scholarly collaboration networks? Nature Blog. https://blogs.nature.com/ofschemesandmemes (2017).

Weisgram, E. S. & Bigler, R. S. Effects of learning about gender discrimination on adolescent girls’ attitudes toward and interest in science. Psychol. Women Q. 31, 262–269 (2007).

Régner, I., Thinus-Blanc, C., Netter, A., Schmader, T. & Huguet, P. Committees with implicit biases promote fewer women when they do not believe gender bias exists. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 1171–1179 (2019).

Klysing, A. Exposure to scientific explanations for gender differences influences individuals’ personal theories of gender and their evaluations of a discriminatory situation. Sex. Roles 82, 253–265 (2020).

McCall, L., Burk, D., Laperrière, M. & Richeson, J. A. Exposure to rising inequality shapes Americans’ opportunity beliefs and policy support. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 9593–9598 (2017).

Peterson, D. A., Biederman, L. A., Andersen, D., Ditonto, T. M. & Roe, K. Mitigating gender bias in student evaluations of teaching. PloS One 14, e0216241 (2019).

Cundiff, J. L., Danube, C. L., Zawadzki, M. J. & Shields, S. A. Testing an intervention for recognizing and reporting subtle gender bias in promotion and tenure decisions. J. High. Educ. 89, 611–636 (2018).

Moss-Racusin, C. A. et al. A “scientific diversity” intervention to reduce gender bias in a sample of life scientists. Life Sci. Educ. 15, ar29 (2016).

Coffman, K. B. Evidence on self-stereotyping and the contribution of ideas. Q. J. Econ. 129, 1625–1660 (2014).

Josephs, R. A., Markus, H. R. & Tafarodi, R. W. Gender and self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 63, 391 (1992).

Bleidorn, W. et al. Age and gender differences in self-esteem-a cross-cultural window. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 111, 396 (2016).

Correll, S. J. Gender and the career choice process: The role of biased self-assessments. Am. J. Sociol. 106, 1691–1730 (2001).

Exley, C. L. & Kessler, J. B. The gender gap in self-promotion. Q. J. Econ. 137, 1345–1381 (2022).

West, J. D. & Bergstrom, C. T. Misinformation in and about science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e1912444117 (2021).

Phelan, J. E. & Rudman, L. A. Prejudice toward female leaders: Backlash effects and women’s impression management dilemma. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 4, 807–820 (2010).

Rudman, L. A. & Phelan, J. E. Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 28, 61–79 (2008).

Moss-Racusin, C. A. & Rudman, L. A. Disruptions in women’s self-promotion: The backlash avoidance model. Psychol. Women Q. 34, 186–202 (2010).

Daubman, K. A., Heatherington, L. & Ahn, A. Gender and the self-presentation of academic achievement. Sex. Roles 27, 187–204 (1992).

Heatherington, L. et al. Two investigations of “female modesty” in achievement situations. Sex. Roles 29, 739–754 (1993).

Shor, E., van de Rijt, A. & Kulkarni, V. Women who break the glass ceiling get a “paper cut”: Gender, fame, and media sentiment. Soc. Prob. 71, 509–530 (2022).

Hagen, R. L. & Kahn, A. Discrimination against competent women. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 5, 362–376 (1975).

Rudman, L. A. & Glick, P. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. J. Soc. Issues 57, 743–762 (2001).

Janoff-Bulman, R. & Wade, M. B. The dilemma of self-advocacy for women: Another case of blaming the victim? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 15, 143–152 (1996).

Rudman, L. A. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 74, 629 (1998).

Altenburger, K., De, R., Frazier, K., Avteniev, N. & Hamilton, J. Are there gender differences in professional self-promotion? An empirical case study of LinkedIn profiles among recent mba graduates. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (2017).

Brooks, A. W., Huang, L., Kearney, S. W. & Murray, F. E. Investors prefer entrepreneurial ventures pitched by attractive men. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 111, 4427–4431 (2014).

Babcock, L., Recalde, M. P., Vesterlund, L. & Weingart, L. Gender differences in accepting and receiving requests for tasks with low promotability. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 714–747 (2017).

Nelson, L. K. et al. Taking the time: The implications of workplace assessment for organizational gender inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 88, 627–655 (2023).

Miller, C. & Roksa, J. Balancing research and service in academia: Gender, race, and laboratory tasks. Gend. Soc. 34, 131–152 (2020).

Christia, F., Larreguy, H., Parker-Magyar, E. & Quintero, M. Empowering women facing gender-based violence amid COVID-19 through media campaigns. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1740–1752 (2023).

Ceci, S. J., Ginther, D. K., Kahn, S. & Williams, W. M. Women in academic science: A changing landscape. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 15, 75–141 (2014).

Kray, L. J., Kennedy, J. A. & Lee, M. Now, women do ask: A call to update beliefs about the gender pay gap. Acad. Manag. Discov. 10, 7–33 (2024).

Recalde, M. P. & Vesterlund, L. Gender differences in negotiation: can interventions reduce the gap? Annu. Rev. Econ. 15, 633–657 (2023).

Sasahara, K. et al. Social influence and unfollowing accelerate the emergence of echo chambers. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 4, 381–402 (2021).

Durbin, S., Lopes, A. & Warren, S. Challenging male dominance through the substantive representation of women: the case of an online women’s mentoring platform. N. Technol. Work Employ. 35, 215–231 (2020).

Kang, H. Y. Technological engagement of women entrepreneurs on online digital platforms: Evidence from the Apple iOS app store. Technovation 114, 102522 (2022).

Maaranen, A. & Tienari, J. Social media and hyper-masculine work cultures. Gend. Work Organ. 27, 1127–1144 (2020).

Crockett, C. & Vogelstein, R. Launching the global partnership for action on gender-based online harassment and abuse. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/gpc/briefing-room/2022/03/18/launching-the-global-partnership-for-action-on-gender-based-online-harassment-and-abuse/ (2022).

Vogels, E. A. The state of online harassment. Pew Res. Center 13. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/ (2021).

McDonald, L., Barriault, C. & Merritt, T. Effects of gender harassment on science popularization behaviors. Public Underst. Sci. 29, 718–728 (2020).

Cooper, M. For women leaders, likability and success hardly go hand-in-hand. Harvard Bus. Rev. 30, 7–16 (2013).

Wang, K. et al. A review of microsoft academic services for science of science studies. Front. Big Data 2, 45 (2019).

Peng, H., Ke, Q., Budak, C., Romero, D. M. & Ahn, Y.-Y. Neural embeddings of scholarly periodicals reveal complex disciplinary organizations. Sci. Adv. 7, eabb9004 (2021).

Teplitskiy, M., Peng, H., Blasco, A. & Lakhani, K. R. Is novel research worth doing? Evidence from peer review at 49 journals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2118046119 (2022).

Zahedi, Z., Costas, R. & Wouters, P. How well developed are altmetrics? A cross-disciplinary analysis of the presence of ‘alternative metrics’ in scientific publications. Scientometrics 101, 1491–1513 (2014).

Altmetric.com. Our sources. https://www.altmetric.com/about-us/our-data/our-sources/ (2023).

Zhu, J. M. et al. Gender differences in twitter use and influence among health policy and health services researchers. JAMA Intern. Med. 179, 1726–1729 (2019).

Costas, R., Mongeon, P., Ferreira, M. R., van Honk, J. & Franssen, T. Large-scale identification and characterization of scholars on Twitter. Quant. Sci. Stud. 1, 771–791 (2020).

Chan, H. F. & Torgler, B. Gender differences in performance of top cited scientists by field and country. Scientometrics 125, 2421–2447 (2020).

Wren, J. D. et al. The write position: A survey of perceived contributions to papers based on byline position and number of authors. EMBO Rep. 8, 988–991 (2007).

Sekara, V. et al. The chaperone effect in scientific publishing. PNAS 115, 12603–12607 (2018).

Hilbe, J. M. Negative binomial regression (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Lerchenmueller, M. J., Sorenson, O. & Jena, A. B. Gender differences in how scientists present the importance of their research: observational study. Br. Med. J. 367, l6573 (2019).

Qiu, H. S. et al. Use of promotional language in grant applications and grant success. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2448696 (2024).

King, M. M., Bergstrom, C. T., Correll, S. J., Jacquet, J. & West, J. D. Men set their own cites high: Gender and self-citation across fields and over time. Socius 3, 2378023117738903 (2017).

Andersen, J. P., Schneider, J. W., Jagsi, R. & Nielsen, M. W. Meta-research: Gender variations in citation distributions in medicine are very small and due to self-citation and journal prestige. eLife 8, e45374 (2019).

Mishra, S., Fegley, B. D., Diesner, J. & Torvik, V. I. Self-citation is the hallmark of productive authors, of any gender. PLOS ONE 13, 1–21 (2018).

Azoulay, P. & Lynn, F. B. Self-citation, cumulative advantage, and gender inequality in science. Sociol. Sci. 7, 152–186 (2020).

Li, W., Zhang, S., Zheng, Z., Cranmer, S. J. & Clauset, A. Untangling the network effects of productivity and prominence among scientists. Nat. Commun. 13, 4907 (2022).

Peng, H., Qiu, H. S., Fosse, H. B. & Uzzi, B. Promotional language and the adoption of innovative ideas in science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2320066121 (2024).

Lockhart, J. W., King, M. M. & Munsch, C. Name-based demographic inference and the unequal distribution of misrecognition. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1084–1095 (2023).

Baugh, S. G. & Graen, G. B. Effects of team gender and racial composition on perceptions of team performance in cross-functional teams. Group Organ. Manag. 22, 366–383 (1997).

Silbiger, N. J. & Stubler, A. D. Unprofessional peer reviews disproportionately harm underrepresented groups in stem. PeerJ 7, e8247 (2019).

Cech, E. A. The intersectional privilege of white, able-bodied heterosexual men in STEM. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo1558 (2022).

Peng, H., Lakhani, K. & Teplitskiy, M. Acceptance in top journals shows large disparities across name-inferred ethnicities. SocArXiv (2021).

Crabtree, C. et al. Validated names for experimental studies on race and ethnicity. Sci. Data 10, 130 (2023).

Deschacht, N. & Maes, B. Cross-cultural differences in self-promotion: A study of self-citations in management journals. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 90, 77–94 (2017).

Stephen, D. & Stahlschmidt, S. Contrasting cross-correlation: Meta-analyses of the associations between citations and 13 altmetrics, incorporating moderating variables. Scientometrics 129, 6049–6063 (2024).

Bardus, M. et al. The use of social media to increase the impact of health research: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e15607 (2020).

Amanatullah, E. T. & Morris, M. W. Negotiating gender roles: Gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 98, 256 (2010).

Ibarra, H. How to do sponsorship right. Harvard Bus. Rev. 100, 11–12 (2022).

Ciampaglia, G. L., Nematzadeh, A., Menczer, F. & Flammini, A. How algorithmic popularity bias hinders or promotes quality. Sci. Rep. 8, 15951 (2018).

Ford, D., Harkins, A. & Parnin, C. Someone like me: How does peer parity influence participation of women on stack overflow? In 2017 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC), 239–243 (IEEE, 2017).

Mongeon, P., Bowman, T. D. & Costas, R. An open data set of scholars on Twitter. Quant. Sci. Stud. 4, 314–324 (2023).

Peng, H., Teplitskiy, M., Romero, D. & Ágnes Horvát, E. Promotion. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Promotion/21843330 (2023).

Peng, H. https://github.com/haoopeng/gender_promotion. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15054468 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Altmetric, IOP Publishing, and Microsoft Academic Graph for sharing the data. The authors thank Inna Smirnova, Orsolya Vásárhelyi, Bogdan Vasilescu, and the Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems workgroup for helpful discussion. This work was partially supported by the City University of Hong Kong Startup Grant No. 9610703 (H.P.), the NSF Career Grant No. IIS-1943506 (E.-Á.H.), and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Award No. FA9550-19-1-0029 (D.M.R.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.P., M.T., D.M.R. and E.-Á.H. designed the research. H.P., M.T., D.M.R,. and E.-Á.H. wrote the paper. H.P. initiated the idea and analyzed the data. H.P. and E.-Á.H. produced the visualizations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

: Nature Communications thanks Ho Fai Chan, Angelica Ferrara, Rachel Hall, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, H., Teplitskiy, M., Romero, D.M. et al. The gender gap in scholarly self-promotion on social media. Nat Commun 16, 5552 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60590-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60590-y