Abstract

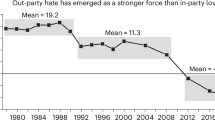

Affective polarization has become a defining feature of twenty-first-century US politics, but we do not know how it relates to citizens’ policy opinions. Answering this question has fundamental implications not only for understanding the political consequences of polarization, but also for understanding how citizens form preferences. Under most political circumstances, this is a difficult question to answer, but the novel coronavirus pandemic allows us to understand how partisan animus contributes to opinion formation. Using a two-wave panel that spans the outbreak of COVID-19, we find a strong association between citizens’ levels of partisan animosity and their attitudes about the pandemic, as well as the actions they take in response to it. This relationship, however, is more muted in areas with severe outbreaks of the disease. Our results make clear that narrowing of issue divides requires not only policy discourse but also addressing affective partisan hostility.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

27,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

118,99 € per year

only 9,92 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available via Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/H7AT3N.

Code availability

All code that supports the findings of this study are available via Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/H7AT3N.

References

Iyengar, S., Sood, G. & Lelkes, Y. Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431 (2012).

Finkel, E. J. et al. Political sectarianism in America: a poisonous cocktail of othering, aversion, and moralization. Science 370, 533–536 (2020).

Partisan Antipathy: More Intense, More Personal (Pew Research Center, 2019); https://pewrsr.ch/3gGRfGp

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N. & Westwood, S. J. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146 (2019).

Fiorina, M. Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate (Hoover Institution Press, 2017).

Rogowski, J. & Sutherland, J. How ideology fuels affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 38, 485–508 (2016).

Levendusky, M. The Partisan Sort (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2009).

Gollwitzer, A. et al. Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 1186–1197 (2020).

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (eds Austin. W. G. & Worchel, S.) 33–47 (Brooks/Cole, 1979).

Groenendyk, E. Competing motives in a polarized electorate: political responsiveness, identity defensiveness, and the rise of partisan antipathy. Polit. Psychol. 39, 159–171 (2018).

Iyengar, S. & Krupenkin, M. The strengthening of partisan affect. Polit. Psychol. 39, 201–218 (2018).

Huber, G. & Malhotra, N. Political homophily in social relationships: evidence from online dating behavior. J. Polit. 79, 269–283 (2017).

McConnell, C., Margalit, Y., Malhotra, N. & Levendusky, M. The economic consequences of partisanship in a polarized era. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 5–18 (2018).

Shafranek, R. Political considerations in nonpolitical decisions: a conjoint analysis of roommate choice. Polit. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09554-9 (2019).

Lelkes, Y. & Westwood, S. J. The limits of partisan prejudice. J. Polit. 79, 485–501 (2017).

West, E. & Iyengar, S. Partisanship as a social identity: implications for polarization. Polit. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09637-y (2020).

Mason, L. Uncivil Agreement (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2018).

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. & Taddy, M. Measuring group differences in high‐dimensional choices: method and application to congressional speech. Econometrica 87, 1307–1340 (2019).

Lelkes, Y. Policy over party: comparing the effects of candidate ideology and party on affective polarization. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.18 (2019).

Lelkes, Y., Sood, G. & Iyengar, S. The hostile audience: the effect of access to broadband internet on partisan affect. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 61, 5–20 (2017).

Levendusky, M. How Partisan Media Polarize America (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2013).

Lau, R. R., Andersen, D. J., Ditonto, T. M., Kleinberg, M. S. & Redlawsk, D. P. Effect of media environment diversity and advertising tone on information search, selective exposure, and affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 39, 231–255 (2017).

Levy, R. Social media, news consumption, and polarization: evidence from a field experiment. SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3653388 (2020).

Pierce, D. & Lau, R. Polarization and correct voting in U.S. Presidential elections. Elect. Stud. 60, 102048 (2019).

Goren, P., Federico, C. & Kittilson, M. Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 805–820 (2009).

Bakker, B., Lelkes, Y. & Malka, A. Understanding partisan cue receptivity: tests of predictions from the bounded rationality and expressive utility perspectives. J. Polit. 82, 1061–1077 (2020).

Nicholson, S. Polarizing cues. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 52–66 (2012).

Tajfel, H. & Wilkes, A. Classification and quantitative judgment. Br. J. Psychol. 54, 101–114 (1963).

Armaly, M. & Enders, A. The role of affective orientations in promoting perceived polarization. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.24 (2020).

Merkley, E. & Stecula, D. Party cues in the news: Democratic elites, Republican backlash, and the dynamics of climate skepticism. Preprint at https://osf.io/azrxm/ (2020).

Milita, K., Ryan, J. B. & Simas, E. Nothing to hide, nothing to run, or nothing to lose: candidate position-taking in congressional elections. Polit. Behav. 36, 427–449 (2014).

Barber, M. & Pope, J. C. Does party trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 38–54 (2019).

Lelkes, Y. Affective polarization and ideological sorting: a reciprocal, albeit weak, relationship. Forum 16, 67–79 (2018).

Bougher, L. The correlates of discord: identity, issue alignment, and political hostility in polarized America. Polit. Behav. 39, 731–762 (2017).

Webster, S. & Abramowitz, A. The ideological foundations of affective polarization in the U.S. electorate. Am. Polit. Res. 45, 621–647 (2017).

Lipsitz, K. & Pop-Eleches, G. The partisan divide in social distancing. SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3595695 (2020).

Fowler, L., Kettler, J. & Witt, S. Democratic governors are quicker in responding to the coronavirus than Republicans. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/democratic-governors-are-quicker-in-responding-to-the-coronavirus-than-republicans-135599 (6 April 2020).

Hart, P. S., Chinn, S. & Soroka, S. Politicization and polarization in COVID-19 news coverage. Sci. Commun. 42, 679–697 (2020).

McCarty, N. Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford Univ. Press, 2019).

Gadarian, S., Goodman, S. & Pepinsky, T. Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Preprint at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3562796 (2020).

Allcott, H. et al. Polarization and public health: partisan differences in social distancing during COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 191, 104254 (2020).

Leeper, T. J. & Slothuus, R. Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Polit. Psychol. 35, 129–156 (2014).

Mullinix, K. Partisanship and preference formation: competing motivations, elite polarization, and issue importance. Polit. Behav. 38, 383–411 (2016).

Groenendyk, E. & Krupnikov, Y. What motivates reasoning? A context-dependent theory of political evaluation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12562 (2020).

Druckman, J. The politics of motivation. Crit. Rev. 24, 199–216 (2012).

Bayes, R., Druckman, J., Goods, A. & Molden, D. When and how different motives can drive motivated political reasoning. Polit. Psychol. 41, 1031–1052 (2020).

Lerman, A. E. & McCabe, K. T. Personal experience and public opinion: a theory and test of conditional policy feedback. J. Polit. 79, 624–641 (2017).

Molden, D. C. & Higgins, E. T. in The Oxford Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning (eds Holyoak, K. J. & Morrison, R. G.) 390–412 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Brambor, T., Clark, W. & Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 14, 63–82 (2006).

Kam, C. & Franzese, R. Modeling and Interpreting Interactive Hypotheses in Regression Analyses (Univ. of Michigan Press, 2009).

Berry, W., Golder, M. & Milton, D. Improving tests of theories positing interaction. J. Polit. 74, 653–671 (2012).

Leeper, T. J. Interpreting regression results using average marginal effects with R’s margins. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Interpreting-Regression-Results-using-Average-with-Leeper/9615c76bd5d81f7ebbbdac9714619863dc3a2337 (2018).

Rieger, J. M. 40 times Trump said the coronavirus would go away. The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/politics/40-times-trump-said-the-coronavirus-would-go-away/2020/04/30/d2593312-9593-4ec2-aff7-72c1438fca0e_video.html (2 November 2020).

Green, J., Edgerton, J. Naftel, D., Shoub, K. & Cranmer, S. Elusive consensus: polarization in elite communication on the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc2717 (2020).

Gollust, S., Nagler, R. & Fowler, E. The emergence of COVID-19 in the U.S.: a public health and political communication crisis. J. Health Polit. Policy Law https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641506 (2020).

Ahler, D. & Sood, G. The parties in our heads: misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. J. Polit. 80, 964–981 (2018).

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M. & Ryan, J. B. Mis-estimating affective polarization. Working Paper Seires WP-19-25 https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/our-work/working-papers/2019/wp-19-25.html (Northwestern Univ. Inst. for Policy Research, 2020).

Levendusky, M. Americans, not partisans: can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? J. Polit. 80, 59–80 (2018).

Wojcieszak, M. & Warner, B. Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? A systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Polit. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406 (2020).

Gerber, A. & Green, D. Misperceptions about perceptual bias. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2, 189–210 (1999).

Fowler, A. Partisan intoxication or policy voting? Q. J. Polit. Sci. 15, 141–179 (2020).

Goren, P. Party identification and core political values. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 882–897 (2005).

Rinehart, R. U.S. face mask usage relatively uncommon in outdoor settings. Gallup (7 August 2020); https://news.gallup.com/poll/316928/face-mask-usage-relatively-uncommon-outdoor-settings.aspx

Baker, P. Trump, in a shift, endorses masks and says virus will get worse. The New York Times (21 July 2020).

Rucker, P. & Kim, S. M. Republican leaders now say everyone should wear a mask—even as Trump refuses and has mocked some who do. The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/republican-leaders-now-say-everyone-should-wear-a-mask--even-as-trump-refuses-and-mocks-those-who-do/2020/06/30/995a32d0-bae9-11ea-80b9-40ece9a701dc_story.html (30 June 2020).

Druckman, J. & Levendusky, M. What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opin. Q. 83, 114–122 (2019).

Beam, M. A., Hutchens, M. J. & Hmielowski, J. D. Facebook news and (de)polarization: reinforcing spirals in the 2016 US election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 940–958 (2018).

Huddy, L., Mason, L. & Aarøe, L. Expressive partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 1–17 (2015).

Linden, A., Mathur, M. & VanderWeele, T. Conducting sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding in observational studies using E-values: the evalue package. Stata J. 20, 162–175 (2020).

VanderWeele, T. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 268–274 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Lin and N. Sands for their research assistance, as well as E. Finkel and E. Groenendyk for feedback. Funding for this study was provided by Northwestern University, the University of Arizona and the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennslyvania. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.N.D. fielded the study and provided the deidentified data. J.N.D., S.K., Y.K., M.L. and J.B.R. designed the research, did preliminary analyses and wrote the manuscript. J.B.R. performed the final analyses and constructed the figures and analyses in Supplementary Information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Alan Abramowitz, Omer Yair and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Aisha Bradshaw.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Ordered sections as referred to in the text of the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Druckman, J.N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y. et al. Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat Hum Behav 5, 28–38 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

This article is cited by

-

How AI sources can increase openness to opposing views

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Affect, Not Ideology: The Heterogeneous Effects of Partisan Cues on Policy Support

Political Behavior (2025)

-

The disinformation lifecycle: an integrated understanding of its creation, spread and effects

Discover Global Society (2025)

-

House divided: executive political heterogeneity and corporate social responsibility

Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting (2025)

-

How Cross-Cutting Ties Reduce Affective Polarization: Evidence from Latino Americans

Political Behavior (2025)