Abstract

Following the COVID-19 outbreak, psychological stress was particularly pronounced in the student population due to prolonged home isolation, online study, closed management, graduation, and employment pressures. The objective of this study is to identify the incidence of psychological stress reactions in student populations following a global outbreak and the associated influencing factors. Four English databases (Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science) and four Chinese biomedical databases (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang) were searched in this study. We also retrieved other search engines manually. The search period was from the time of database creation to 10 March 2022. This study included cross-sectional studies related to psychological stress reactions in student populations during the COVID-19 epidemic. Three groups of researchers screened the retrieved studies and assessed the quality of the included studies using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Cross-Sectional Study Quality Assessment Checklist. A random-effects model was used to analyze the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and fear symptoms in the student population during the COVID-19 epidemic. Of the 146,330 records retrieved, we included 104 studies (n = 2,088,032). The quality of included studies was moderate. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the student population during the epidemic was 32.0% (95% CI [28.0–37.0%]); anxiety symptoms was 28.0% (95% CI [24.0–32.0%]); stress symptoms was 31.0% (95% CI [23.0–39.0%]); and fear symptoms was 33.0% (95% CI [20.0–49.0%]). The prevalence differed by gender, epidemic stage, region, education stage, student major and assessment tool. The prevalence of psychological stress in the student population during the COVID-19 epidemic may be higher compared to the global prevalence of psychological stress. We need to alleviate psychological stress in the student population in a targeted manner to provide mental health services to safeguard the student population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), COVID-19 has rapidly spread to more than 200 countries and territories. Many countries have entered Level One Public Health Emergencies response. There were more than 500 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 6 million deaths as of 17 April 20221. The outbreak and expansion of the epidemic significantly affect the mental health status of the population2. The student population was also greatly affected by the epidemic, taking into account a variety of factors, such as prolonged home isolation, closed campus management, online learning, graduation, and employment pressures.

During serious public health emergencies, populations are more likely to experience psychological changes such as depression, anxiety, fear, and stress symptoms3. As a vulnerable group, students are more prone to mental health problems than people with stable incomes. The prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in the Chinese student population during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003 ranged from 25.4 to 29.6%. This value was much higher than the results of the population mental health survey at that time (7.6–16.3%)4. Strong and persistent psychological stimuli in the student population can trigger psychological stress reactions, mainly in the form of mood changes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and fear symptoms. It can also be accompanied by symptoms such as palpitations, irritability, headaches, insomnia, and in severe cases, disruptions in the function of several systems5 and even lead to dependent behavior of students on alcohol, tobacco, drugs, and smartphones6,7. As a result, this can have a negative impact on the health and life of the student body. Therefore, mental health services and emotional stress interventions for the student population are also an important part of the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic and the promotion of future development dynamics in society.

The existing meta-analyses have either focused only on mood changes in anxiety and depression in student populations or have been limited to studies of student populations in a particular major or country8,9. Nevertheless, the psychological stress response in student populations is influenced by a variety of factors, such as gender, major, regional economic status, and educational stage. Moreover, the prevalence of psychological stress varies widely across studies, which greatly increases the difficulty of developing psychological intervention programs for student populations.

Our meta-analysis collected cross-sectional studies related to psychological stress in student populations globally since the onset of the epidemic to comprehensively and completely assess the psychological stress in student populations. The gender, major, academic stage, regional nuclear study phase of the epidemic, and survey approach of the student population in the study were further explored. This study was designed to provide a reference for the prevention and intervention of psychological stress reactions in student populations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We conducted this meta-analysis according to the PRISMA guidelines. The protocol of this study is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Evaluations (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42020210391.

Literature search

In this study, four Chinese databases and four English databases were searched, including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data, CQVIP, China Biomedical Literature (SinoMed), Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The search period was from the establishment of the database to March 10, 2022. According to the "PICOS" principle to formulate the search strategy, we used search terms including: “novel coronavirus pneumonia”, “NCP”, “2019-nCoV”, “COVID-19”, “coronavirus disease 2019”, “mental health”, “depression”, “anxiety”, “fear”, “stress”. The combination of subject words and free words was used in the retrieval, and the references that had been included in the literature were supplemented. In addition, we supplemented the search with relevant literature found by search engines such as Google Scholar. A detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for eligible studies were: (a) the type of study included was a cross-sectional study (on-site survey or online survey); (b) the study population was the student population during the epidemic, including undergraduates, postgraduates, middle school students, and primary school students; (c) Assessing the prevalence of depression, anxiety, fear and stress symptoms using a standardized instrument or an evidence-based, self-administered scale instrument; (d) the inclusion study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (since December 19, 2019). Exclusion criteria were: (a) the college or university students with mental illness already; (b) The study did not provide separate results or complete outcome data for the incidence of psychological stress in the student population.

Data Extraction

Using a pre-designed spreadsheet, we extracted the following information from the included studies: first author, date of publication, study period, sampling method, the region where the study was conducted, sample size, characteristics of the study sample, evaluation instrument, survey method, and incidence of psychological stress (depression, anxiety, fear, stress).

Quality assessment

We evaluated the quality of included studies using the criteria of the American Agency for Health Care Quality and Research Cross-Sectional Research Literature Quality Assessment Checklist (AHRQ Checklist)10. A total of 11 entries were available. The evaluation was done with "yes," "no," and "unclear" responses, with 0–3 being low quality, > 3–7 is medium quality, and > 7–11 being high quality.

Three groups of researchers (Yang Fang, Jingyu Zhang; Yitian Liu, Yana Xie; Yunpeng Ge, Qianwei Liu) independently performed literature screening, data extraction, and literature bias assessment. When disagreements emerged in the assessment, they were checked for discrepancies or disputes by discussing or consulting third-party solutions.

Data synthesis and analysis

We used meta-analysis to generate pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the prevalence of depression, anxiety, fear, and stress symptoms in the entire sample. We used forest plots to show incidence and pooled estimates, while I2 tests were used to assess heterogeneity between studies. Fixed-effects models assume that the overall effect size is the same for all studies. In contrast, the random-effects model attempts to do this by assuming that the selected studies are from a larger population.11 When evidence heterogeneity was low (i.e., I2 ≤ 50 and heterogeneity p ≥ 0.10), a fixed-effects model was used to generate pooled estimates; otherwise, a random-effects model was used. We used subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity in the incidence of different psychological stress responses. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Begg's test, as Begg's test is more applicable for large meta-analyses that include 75 or more original studies12. The incidence was transformed by the "PFT" method before the meta-analysis. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.0).

Results

Literature screening

Initially, 146,330 studies on this subject were searched through 8 databases and 2 studies were searched manually; subsequently, we removed 86,428 duplicate studies and 86,324 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria for this study. A total of 104 studies were finally included in this meta-analysis13. The flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. A total of 104 cross-sectional studies with 2,088,032 students were included in this study. Of these, 988,425 were males, 1,098,969 were females, and 638 were of unknown gender. Of the included studies, 75 studies reported depressive symptoms (n = 1,005,228), 93 studies reported anxiety symptoms (n = 2,048,035), 31 reported stress symptoms (n = 855,564) and 17 studies reported fear symptoms (n = 62,346). 86 studies were conducted in Asia, 8 in Europe, 5 in Africa, 1 in South America, 3 in North America, and 1 in Oceania. Regarding sampling methods, a total of 11 studies used random sampling, 3 studies used stratified sampling, 6 studies used whole group sampling, and the remaining studies used convenience sampling. Regarding the included studies, 36 studies assessed depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module-9 (PHQ-9), 8 studies assessed depressive symptoms using the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS); 39 studies assessed anxiety symptoms using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 Item Scale (GAD-7), 23 studies assessed anxiety symptoms using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS); 17 studies assessed psychological stress reactions using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 Item (DASS-21), 3 studies assessed psychological stress reactions using the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90), 3 studies assessed psychological stress reactions using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the other studies used self-administered scales or other assessment scale tools.

Study quality

Among the included studies, a total of 8 studies had a quality score of “0–3”, 78 studies had a quality score of “4–7”, and 18 studies had a quality score of “8–11”. The quality of the included studies was moderate. The specific evaluations are shown in Table 2.

The pooled prevalence of depressive symptom

The results of the meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms in the student population was 32.0% with high heterogeneity (95% CI [28.0 ~ 37.0%], I2 = 100%, p < 0.001; Fig. 2). No statistically significant publication bias was found in the included 75 studies by Begg’s test (p = 0.6116 > 0.05). Sensitivity analysis results showed no obvious change in effect values when single studies were excluded one by one and then subjected to Meta-analysis, suggesting more stable study results.

The pooled prevalence of anxiety symptom

The results of the meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms in the student population was 28.0% with high heterogeneity (95% CI [24.0 ~ 32.0%], I2 = 100%, p < 0.001; Fig. 3). No statistically significant publication bias was found in the included 93 studies by Begg’s test (p = 0.9233 > 0.05). Sensitivity analysis results showed no obvious change in effect values when single studies were excluded one by one and then subjected to Meta-analysis, suggesting more stable study results.

The pooled prevalence of stress symptom

The results of the meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of stress symptom in the student population was 31.0% with high heterogeneity (95% CI [23.0 ~ 39.0%], I2 = 100%, p < 0.001; Fig. 4). No statistically significant publication bias was found in the included 31 studies by Begg’s test (p = 0.1430 > 0.05). Sensitivity analysis results showed no obvious change in effect values when single studies were excluded one by one and then subjected to Meta-analysis, suggesting more stable study results.

The pooled prevalence of fear symptom

The results of the meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of fear symptoms in the student population was 33.0% with high heterogeneity (95% CI [20.0 ~ 49.0%], I2 = 100%, p < 0.001; Fig. 5). The Begg’s test found statistically significant publication bias in the 17 included studies (p = 0.0238 < 0.05). Sensitivity analysis results showed no obvious change in effect values when single studies were excluded one by one and then subjected to Meta-analysis, suggesting more stable study results.

Subgroup analysis

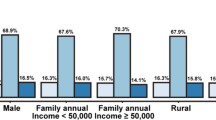

Subgroup analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and fear symptoms in the student population was influenced by gender, the period of the epidemic, the region, the stage of education, the student’s major, and the instrument used in the evaluation.

The prevalence of depression (36.0%, 95% CI [28.0–44.0%]), anxiety (27.0%, 95% CI [21.0–33.0%]), and stress (19.0%, 95% CI [12.0–28.0%]) symptoms was higher among females than males in the student population. Among the geographic regions, the prevalence of psychological stress in the student population was lower in Eastern Asia than in other regions. For students at different educational levels, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms were higher in undergraduate and postgraduate students than in primary school and middle school students, while the prevalence of stress symptoms was the same in undergraduate and postgraduate students as in middle school students. In addition, non-medical students had higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms than medical students. It is noteworthy that as the epidemic progressed from the early outbreak phase to the current "normalized" management phase, the incidence of psychological stress in the student population increased rather than decreased. All details of the subgroup analysis are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

Since the outbreak of the epidemic, COVID-19 has spread rapidly to many countries and regions. As a vulnerable group in the population, the COVID-19 epidemic not only threatens the life and health of the student population but also triggers multiple psychological stress reactions. By identifying the types of students' psychological stress reactions and understanding the influence of relevant factors on the incidence of students' psychological stress reactions, this study can better help us identify individuals in the student population who are more likely to experience psychological stress reactions and develop relevant mental health intervention plans in a targeted manner.

Occurrence of psychological stress in student populations

Our study found that the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and fear symptoms in the student population during the COVID-19 outbreak was 32.0, 28.0%, 31.0, and 33.0%. Related studies reported that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in the general population during the New Coronation epidemic were 28.0, 26.9, and 8.1%14,15. This result suggests that the prevalence of psychological stress in the student population during the New Coronation epidemic was slightly higher than that in the general population. We also found differences in the incidence of psychological stress reactions due to factors such as students' country of residence, stage of education, stage of the epidemic, profession, and the instruments evaluated in the studies. For instance, some studies collected samples only from student populations in medical schools16; others conducted sampling only in primary and secondary schools17; and others sampled only in a fixed area of a particular country18, etc. These differences in study design may be the main source of heterogeneity. Overall, the student population had a higher incidence of psychological stress during the COVID-19 outbreak than before the outbreak19,20.

Vulnerable populations of psychological stress among students

From the subgroup analysis of several predictors identified in the study, we found a greater effect of gender, educational stage, and student major on the incidence of psychological stress reactions in students.

Female student population

Our study revealed that the prevalence of psychological stress in the female student population during the COVID-19 epidemic was much higher in depression (36.0%), anxiety (27.0%), and stress (19.0%) symptoms than in males students. This suggests that the female student population is more prone to psychological. Even before the COVID-19 outbreak, the prevalence of symptoms such as depression and anxiety was significantly higher in female than in the male population21,22. Females are more emotionally expressive than males, their mental and emotional states are more susceptible to external factors than males, and females show different neurobiological responses when exposed to stressors23,24. Psychological and physiological differences between females and males may provide a basis for the finding that female student populations are more prone to psychological stress reactions.

Undergraduate and postgraduate student population

Our study found that the undergraduate and postgraduate student population also exhibited a higher prevalence of psychological stress during the epidemic, which is consistent with previous research findings25. The reasons for this outcome are multi-layered: on the one hand, a large proportion of undergraduate and postgraduate students may not be able to return to school because of the epidemic. Reduced learning efficiency in distance online education, prolonged lack of social activities, postponement of relevant professional exams, delayed academic progress and pressure to graduate may have caused them to suffer additional psychological and emotional distress26; On the other hand, most the undergraduate and postgraduate students are resident on campus, and the long-term effects of the epidemic have left them with much less opportunity to see their families; In addition, the unemployment and unpredictability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will cause additional strain on graduating undergraduate and postgraduate students.

Non-medical student population

Previous studies have reported higher prevalence of psychological stress among medical students compared to the social population during the COVID-19 epidemic8,27. Our study found that non-medical students exhibited higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms compared to medical majors. We speculate that this may be because medical students are more knowledgeable about COVID-19 and are relatively less susceptible to news and internet information about COVID-1928,29; medical students can apply what they have learned to self-regulate and reduce the level of psychological stress; medical students can also use what they have learned to participate in the prevention and control of the COVID-19 outbreak by helping to alleviate the psychological stress of their surrounding housemates, classmates or colleagues30. In addition, most medical students' families are relatively well-off and will be less affected by the epidemic, which makes medical students worry-free in this regard. This result suggests that we should pay more attention to mental health issues of non-medical students and provide education and counseling with knowledge about COVID-19.

African and South American Student population

Our study found that psychological stress occurs more severely in student populations in Africa and South America than in other regions. Regional social conditions such as poor economic status, low education, and unemployment are important risk factors for triggering psychological stress during the COVID-19 pandemic31. The relatively tight medical resources, the high socioeconomic impact of the epidemic shock, and the dissemination of information related to COVID-19 contributed to the significantly higher incidence of psychological stress among students in these regions.

Rehabilitation of students’ psychological stress in the “post-epidemic era”

Our study revealed a different result from previous research. Psychological stress in the student population increased rather than decreased during the "normalization" phase of the epidemic compared to the early outbreak phase9,32. This result suggests that the factors influencing the psychological stress response of the student population may be multidimensional and multifaceted, not only limited to the severity of the epidemic but also influenced by the students' family situation, graduation and employment pressures, personal exposure to concentrated isolation and uncertainty of information related to the epidemic33. Although the epidemic is not as severe at this stage as it was during the initial outbreak, mental health problems persist in the student population. We should pay more attention to the recovery of the mental health of the student population in the "post-epidemic era" and develop targeted mental health assessments and intervention programs for students. These evaluations and interventions include Internet cognitive behavioral therapy, personal psychoneuroimmune prevention, and Chinese music therapy, among others34,35.

Strengths and limitations

This study systematically and comprehensively collected studies related to psychological stress reactions in student populations worldwide since the onset of the pandemic, to provide a more complete assessment of psychological stress reactions in student populations since the onset of COVID-19, and to analyze the relevant influencing factors and susceptible populations of psychological stress reactions in student populations. This can provide a reference for the development of prevention and intervention programs to address psychological stress in student populations during a global pandemic.

The following problems remain in this study: first, the included studies were mainly focused on the Asian region, with a small number of studies from other regions, which makes the assessment of the incidence of psychological stress in student populations across global regions somewhat biased and limits the generalizability of the findings; second, although we assessed the possible sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analysis, the incidence of psychological stress in student populations still there was a high level of heterogeneity, and this heterogeneity may be due to unidentified relevant factors that need to be further studied and explored; third, the majority of the included studies had a moderate quality rating. Based on the quality evaluation of the literature we suggest that more attention should be paid to the quality control of studies in future studies, especially for the treatment of confounding influences, the treatment of missing data, and the reporting of follow-up; fourth, although we conducted appropriate analyses of psychological stress in the student population during the epidemic, there were differences in the participants in the study and future longitudinal data are needed to examine the psychological stress response symptoms in the student population during the epidemic.; fifth, this meta-analysis could not determine the effect of COVID-19 infection on the psychological stress response of the student population because we did not include separate cohorts of students infected with COVID-19 and those not infected with COVID-19 in each study; finally, few of the included studies described or compared mental health services or related interventions, which prevented us from exploring which interventions better alleviated psychological stress symptoms in the student population.

Both now and in the future, when the epidemic is still prevalent, it is critical to identify the psychological stress profile of the student population and the associated influencing factors and to develop targeted mental health interventions. Future research should focus on interventions and protection against the onset of psychological stress in student populations, identify effective treatments, and develop targeted mental health service plans.

Conclusion

Our study showed a significant increase in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and fear symptoms in the student population during the COVID-19 epidemic. Psychological stress was more pronounced in female students, undergraduate students, graduate students, and non-medical students. This suggests that a series of effective measures should be taken by individuals, families, schools, society, and government to target and alleviate the psychological stress reactions of the student population and to provide mental health service protection for the student population.

Data availability

The datasets provided in this study can be found in online databases. The names and URLs of the databases are in the supplementary material of the article.

References

WHO. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/ (2022).

Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., Jiang, W. & Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 291, 113190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729 (2020).

Kunzler, A. M. et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Global Health 17, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00670-y (2021).

Liu, Q. W. et al. Analysis of the influence of the psychology changes of fear induced by the COVID-19 epidemic on the body: COVID-19. World J. Acupunct. Moxibustion 30, 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wjam.2020.06.005 (2020).

Allen, H. K., Cohen-Winans, S., Armstrong, K., Clark, N. C. & Ford, M. A. COVID-19 exposure and diagnosis among college student drinkers: Links to alcohol use behavior, motives, and context. Transl. Behav. Med. 11, 1348–1353. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibab059 (2021).

Du, C. et al. The effects of sleep quality and resilience on perceived stress, dietary behaviors, and alcohol misuse: A mediation-moderation analysis of higher education students from Asia, Europe, and North America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020442 (2021).

Mulyadi, M., Tonapa, S. I., Luneto, S., Lin, W. T. & Lee, B. O. Prevalence of mental health problems and sleep disturbances in nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 57, 103228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103228 (2021).

Deng, J. et al. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 301, 113863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113863 (2021).

Smetana, G. W., Umscheid, C. A., Chang, S. & Matchar, D. B. Methods guide for authors of systematic reviews of medical tests: A collaboration between the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Journal of General Internal Medicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 27(Suppl 1), S1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2053-1 (2012).

Cheung, M. W., Ho, R. C., Lim, Y. & Mak, A. Conducting a meta-analysis: Basics and good practices. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 15, 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01712.x (2012).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101 (1994).

Factors Associated With Mental Health Disorders Among University Students in France Confined During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PMID: 33095252 PMCID: PMC7584927. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591 (2020).

Nochaiwong, S. et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 11, 10173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028 (2020).

Hakami, Z. et al. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on dental students: A nationwide study. J. Dent. Educ. 85, 494–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12470 (2021).

Lopes, A. R. & Nihei, O. K. Depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in Brazilian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Predictors and association with life satisfaction, psychological well-being and coping strategies. PLoS ONE 16, e0258493. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258493 (2021).

Sundarasen, S. et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 and lockdown among university students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176206 (2020).

Werner-Seidler, A., Perry, Y., Calear, A. L., Newby, J. M. & Christensen, H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005 (2017).

Davies, E. B., Morriss, R. & Glazebrook, C. Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 16, e130. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3142 (2014).

Burke, N. L. & Storch, E. A. A meta-analysis of weight status and anxiety in children and adolescents. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 36, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1097/dbp.0000000000000143 (2015).

Lim, G. Y. et al. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 8, 2861. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x (2018).

Oyola, M. G. & Handa, R. J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes: Sex differences in regulation of stress responsivity. Stress 20, 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2017.1369523 (2017).

Eid, R. S., Gobinath, A. R. & Galea, L. A. M. Sex differences in depression: Insights from clinical and preclinical studies. Prog. Neurobiol. 176, 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.01.006 (2019).

Li, Y., Wang, A., Wu, Y., Han, N. & Huang, H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 12, 669119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669119 (2021).

Cao, W. et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 (2020).

Lasheras, I. et al. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186603 (2020).

Aynalem, Y. A. et al. Assessment of undergraduate student knowledge, attitude, and practices towards COVID-19 in Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16, e0250444. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250444 (2021).

Mena-Tudela, D., González-Chordá, V. M., Andreu-Pejó, L., Mouzo-Bellés, V. M. & Cervera-Gasch, Á. Spanish nursing and medical students’ knowledge, confidence and willingness about COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 103, 104957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104957 (2021).

Tran, B. X. et al. Mobilizing medical students for COVID-19 responses: Experience of Vietnam. J. Glob. Health 10, 020319. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.020319 (2020).

Nicola, M. et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 78, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Bao, X., Yan, J., Miao, H. & Guo, C. Anxiety and depression in Chinese students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 9, 697642. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.697642 (2021).

Xiong, J. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 (2020).

Zhang, M. W. & Ho, R. C. Moodle: The cost effective solution for internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) interventions. Technol. Health Care 25, 163–165. https://doi.org/10.3233/thc-161261 (2017).

Tan, W. et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the 2020 Emergency Research Project on Prevention and Treatment of Major Infectious Diseases of the College of Acupuncture, Moxibustion and Tuina of Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 82174505).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F., B.J., Y.T., and J.Z.: concept and design. B.J. and C.L.: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Y.F.: statistical analysis. All authors: acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Y., Ji, B., Liu, Y. et al. The prevalence of psychological stress in student populations during the COVID-19 epidemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 12, 12118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16328-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16328-7

This article is cited by

-

The impact of COVID-19 quarantine on college students’ mental health

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

The relationship between physical activity, life satisfaction, emotional regulation, and physical self esteem among college students

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Negative Life Events and Negative Emotions among Chinese College Students: The Chain Mediating Roles of Social Phobia and Insomnia

Psychiatric Quarterly (2025)

-

Psychological Problems and Academic Motivation in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study One Year after the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy

Psychiatric Quarterly (2025)

-

An umbrella review of the prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: Call to action for post-COVID-19 at the global level

BMC Public Health (2024)