Abstract

Based on Chinese Students’ Fitness Health Examination, this study sought to investigate the relationships between depressive symptoms and family environment, physical activity, dietary habits, sleep and sedentary behavior among children and adolescents. A cross-sectional study was carried out to estimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms in 32,389 participants (grades 4-12) using the CES-D. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationships between lifestyle determinants and depressive symptoms, and a random forest model was used to rank the importance of those determinants. The overall prevalence of depressive symptoms was 39.93%. Students with depressive symptoms had higher grades, lower parental educational levels and unhealthy lifestyles (P < 0.05). The top ten most important determinants of depressive symptoms were grade, egg intake, milk/soy product intake, frequency of muscle strength training, screen time, sleep duration, parental educational level, sugar beverage intake and total physical activity. Socioeconomic status, physical activity, sleep and screen time, and diet habits are determinants of depressive symptoms, and surveillance of lifestyles may be an effective way to detect students with depressive symptoms early.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a common mental disorder that is characterized by persistent sadness and a lack of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding or enjoyable activities1,2. Globally, depression is the number one cause of illness and disability for children and adolescents aged 10-18 years3. According to the latest estimates from the WHO, approximately 280 million people in the world have depression, and 14% of 10-19-year-olds experience mental health conditions, yet these remain largely unrecognized4. A survey in India reveals that nearly half of the adolescents are afflicted with depression, 5% of whom suffer from severe depression, 6% of whom experience moderate depression, and 34% of whom experience mild depression5.

According to the DSM-5, depression is characterized by five or more symptoms that persist for at least two weeks, such as feelings of worthlessness, decreased interest in activities, changes in appetite or weight, insomnia, restlessness, and thoughts of suicide or death2. However, owing to the social stigma associated with mental disorders, many students are hesitant to access mental health services, limiting the ability of psychiatrists to diagnose depression6. Therefore, the use of a screening instrument can assist in boosting the rate of mental health assessments among students, thus aiding in the identification and diagnosis of depression before any psychiatric consultation7.

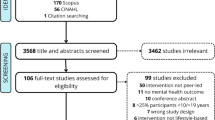

The causes of depression include complex interactions between social, psychological and biological factors. Lifestyle factors, together with socioeconomic factors, have a large impact on mental disorders in children and adolescents8,8,10. However, most studies on depression and lifestyle involve only a few lifestyle factors, and comprehensive analyses of the determinants of depression among children and adolescents are scarce. Therefore, this study randomly selected 32,389 primary and middle school students (from the fourth grade of elementary school to the third grade of high school) who participated in the Students’ Fitness Health Examination (SFHE) in 2019-2020 to explore the associations of socioeconomic status, physical exercise, diet habits, sleep and screen time with the prevalence of depressive symptoms and to determine the importance of those variables by adopting a random forest model.

Method

Study design and population

By adopting a cross-sectional study design, this study was conducted from 2019 to 2020 in China. A total of 32,389 participants (grades 4-12) were randomly recruited from three provinces (Shandong, Chongqing, Guangdong) to complete an online questionnaire under the guidance of regional administrators, physical education teachers and graduate students. Two primary schools, two junior high schools and two senior high schools were randomly chosen from city and rural areas, respectively, in each city, with approximately 120 students (3-4 classes) recruited from each school in each grade. Parents and students provided written consent prior to enrollment in this survey. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Sport University (2022018), and all methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurements

Data regarding participants’ depressive symptoms, lifestyles, and family demographics were collected using three questionnaires that were developed collaboratively by a multidisciplinary team of researchers.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a self-reported, generic measure of depression validated for children and adolescents. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version have been validated and reported previously11. The CES-D questionnaire included 20 items, and each item used a four-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 0 to 3); thus, the total CES-D score ranged from 0 to 60 points, with higher scores indicating a greater probability of depression. CES-D scores greater than or equal to 16 were considered to indicate suspected depression12,12,14, thus individuals with CES-D scores greater than or equal to 16 were considered as the depression group in this study.

The participants’ lifestyles included physical activity and exercise, diet, sleep and screen time. The physical activity level (PA) of the participants was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). This questionnaire is a self-reported measure of physical activity and has been used widely in a variety of research studies. The IPAQ was used to calculate the overall physical activity level (MET-min/wk) by using the following equation: 8.0 METs × total duration of vigorous activity + 4.0 METs × total duration of moderate activity + 3.3 METs × total duration of walking15. Exercise included exercise frequency, exercise time, feeling in exercise, days of physical education classes, and muscle strength training frequency. Data on dietary habits, including the frequency of consuming breakfast, milk/soy products, eggs and sugar beverages, were collected. Sleep duration was calculated by asking about the time of getting sleep and getting up in the past month, and time spent napping was obtained via a direct questionnaire. The screen time survey collected the average time spent using electronic devices (watching TV, playing games with mobile phones, tablets, video games, computers, etc., watching videos or e-books, etc.) every weekday and weekend in the past week.

The participants’ socioeconomic factors included residential ___location (urban or rural), parents’ educational level, and whether the participant was the only child of the family.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to describe participants’ demographic characteristics and prevalence of depressive symptoms. The standardized prevalence of depressive symptoms in students with different lifestyles was adjusted for grade, sex, and urban/rural area. Logistic regression was used to explore the associations between individual lifestyles and depressive symptom after adjusting for grade, sex, and urban/rural area, and the effect sizes (odds ratio (OR)) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Furthermore, machine learning was used to rank variable importance16,17. For comparing model performance, we adopted random forest, artificial neural network, decision tree algorithm, and logistic regression algorithms to develop models in the training set (2/3 participants), and assessed model performance in the validation set (1/3 participants), by using area under the ROC curve (AUC), classification accuracy (ACC), balanced error rate (BER), false positive rate (FPR), positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) as the evaluation18. The random forest model performed best (see supplementary Fig. 1 and supplementary Table 2) thus we adopted random forest model to rank variable importance. Imputation method had been extensively applied to account for missing data, by adopting “missForest” package19, and further sensitive analysis were conducted by adjusting for different sets of possible confounders.

SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R 4.2.0 were used in this study.

Results

Among the 32 389 participants, 12 932 (39.93%) had a CES-D score ≥ 16. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 39.9% (6461/12301) in males and 40.0% (6471/16189) in females, with no significant difference between the sexes (P = 0.870). The prevalence of depressive symptoms increased significantly with increasing grade (P < 0.001), and the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 42.5% (7007/16498) in urban students and 37.3% (5925/15892) in rural students (P < 0.001). The grade-, sex-, rural/urban-specific prevalence of depressive symptoms is shown in Fig. 1, and the baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Students with depressive symptoms had higher grades, lived in the city, had lower parental educational levels, and had unhealthy lifestyles. They performed less exercise and muscle strength training, participated in fewer physical education classes, and had lower metabolic equivalents of physical activity. Students who were depressed tended to skip breakfast, consume fewer eggs and milk/soy products, and consume more sugary drinks. They slept less, took shorter naps, and spent more time watching television (p < 0.05).

The crude prevalence and grade-, sex-, rural/urban-adjusted prevalence of depressive symptoms, as well as the logistic regression model, are shown in Table 2. Only children had a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms than non-only children (OR (95%CI) = 0.85 (0.80-0.90), P < 0.001), and a higher parental educational level was a protective factor against depressive symptoms (P < 0.05). An increased number of days participating in exercise, increased duration of exercise per day, increased number of physical education classes per week, and increased total physical activity per day were protective factors against depressive symptoms (P < 0.05). Specifically, children taking muscle strength 5 + times per week had 74% lower risk of depressive symptoms than children do not taking muscle strength (OR (95%CI) = 0.26(0.23-0.29), P < 0.001), indicating the importance of muscle strength in the prevention of mental disorders. A healthy diet and adequate sleep were protective factors against depressive symptoms in students, e,g, children having 10 + hours of sleep had 77% lower risk of depressive symptoms than children having less than 8 h of sleep (OR (95%CI) = 0.23(0.20-0.26), P < 0.001). While the risk of depressive symptoms for children having sugary drinks more than 5 times/week was 2.07 (95%CI = 1.68-2.54, P < 0.001) times than those do not have sugary drinks, and screen time was also a risk factor for depressive symptoms (OR (95%CI) of 60 + minutes vs. <10 min per day = 2.07(1.91-2.25), P < 0.001).The results were almost the same in imputed dataset (results not shown), and robust after adjusting for different confounding variables (see supplementary Table 3).

Additionally, random forest models were applied to rank the importance of all the variables, and the ten most important factors for depressive symptoms were grade, egg intake, milk/soy product intake, number of muscle strength training sessions, screen time, sleep duration, parents’ educational level, sugar beverage intake and total physical activity (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of depressive symptoms was 39.93% in Chinese primary and middle school students, which was greater than we expected. The questionnaire we used to measure depressive symptoms was CES-D questionnaire, which was a questionnaire used world-wide and had been used successfully across wide age ranges20. The CES-D also provides cutoff scores (e.g., 16 or greater) that aid in identifying individuals at risk for clinical depression, with good sensitivity and specificity and high internal consistency14. One meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms generally increased over time, and the prevalence estimate was 26.3% (95% CI, 21.9-30.8%) in China among children and adolescents; the prevalence widely varied across studies, ranging from 4.41-55.7%21,22. As depression has been a major public health problem for children and adolescents, more efforts should be made to prevent depression and other mental health issues23. A significant association between lifestyle factors and depressive symptoms was observed in our data, and the ten most important factors for depressive symptoms were grade, egg intake, milk/soy product intake, number of muscle strength training sessions, screen time, sleep duration, parents’ educational level, sugar beverage intake and total physical activity, which indicated that lifestyle factors, including getting adequate sleep, eating a healthy diet, and staying physically active and away from screens, could be potential determinants of depression in children and adolescents2.

Physical activity and exercise have long been considered helpful in promoting mental health24,25. Recent researches have suggested that physical activity may be even more effective in preventing depression in children and adolescents than in adults26,27. In China, the importance of physical activity for mental health has been increasingly recognized, and there is growing evidence that it could have a positive impact on depression in children and adolescents28,29. The mechanism might be that exercise improves mood by enhancing the utilization of neurotransmitters such as 5-HT, dopamine, and norepinephrine30. The results of this study suggested that attention should be given to students who perform infrequent exercise, and it is recommended that schools create a good exercise atmosphere to improve physical health of students for the prevention of depression.

Our analysis revealed that dietary habits play an important role in influencing the prevalence of depressive symptoms. Researches have demonstrated that a healthy diet could help to reduce the risk of depression and anxiety, as well as improve overall mood and cognitive function31,32. Meat, eggs, milk and beans are high-quality proteins that contain relatively high amounts of tryptophan, with 200-455 mg per 100 g33. Moreover, studies have suggested that those who consumed a greater proportion of processed food, such as packaged snacks, fast food, and sweetened drinks, were more likely to be depressed than those who consumed more fresh fruits and vegetables34,35. Animal experiments also showed that large amounts of added sugar could increase anxiety and depressive behaviors as well as cortisol levels, which affected the maturation of the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal axis, causing disruptions in the stress regulation system and thus increasing the risk of depression35.

Screen time has been linked to a variety of mental health issues, including depression, in children and adolescents36. Studies have shown that the more time children and adolescents spend on screens, the more likely they are to experience depressive symptoms37,38. In China, screen time based behavior is significantly associated with depression risk and the effects vary in different populations37. Furthermore, more screen time might lead to reduced physical activity, social isolation, and sleep deprivation, all of which could increase the risk of depression39.

Additionally, less sleep time could be a risk factor for depression in children and adolescents. Studies have shown that inadequate sleep could lead to an increased risk of depression in both children and adolescents, while an increased duration of sleep has been associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms40,40,42. Thus, it is important for parents and healthcare providers to be aware of the potential effects of inadequate sleep on mental health in children and adolescents and to ensure that they are getting the amount of sleep recommended for their age.

Random forest models were used to rank variable importance in this study as it perform best, after comparing it with other machine learning methods. Because strong correlations between variables existed in this study, random forest model as a machine learning method was adopted as it could handle nonlinear and coassociation problems43. The results of the random forest model showed that the most important determinants for depressive symptoms were grade, diet, exercise, sleep and screen time, which supported the early detection and prevention of depression through behavioral lifestyle surveillance. Therefore, ensuring a balanced lifestyle, healthy eating, enough sleep, time away from screens, and time for physical activity could help reduce the risk of developing depression.

In summary, this research investigated the associations of socioeconomic status, physical activity, sleep and screen time, and diet with depression in children and adolescents by utilizing a large-scale field survey and revealed that surveillance of lifestyles could help early-detection of students with depressive symptom. The limitations of this study included the lack of confidence in defining depression by self-reported scales as well as the lack of causal-effect relationships by adopting a cross-sectional study design. Further research should be conducted through longitudinal studies to gain more insight into the causal effects of lifestyles on the prevention of depression.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S. & Thapar, A. K. Depression in adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 379, 1056-1067 (2012).

Friedman, H. S. Encyclopedia of Mental Health, Second Edition. Waltham: Academic Pres, 11-19 (2016).

Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health of WHO. Health for the World’s Adolescents (Geneva:World Health Organization, 2014).

Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (2023).

Gupta, S. & Basak, P. Depression and type D personality among undergraduate medical students. Indian J. Psychiatry. 55, 287-289 (2013).

Kim, E. J., Yu, J. H. & Kim, E. Y. Pathways linking mental health literacy to professional help-seeking intentions in Korean college students. J. Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 27, 393-405 (2020).

Leslie, K. R. & Chike-Harris, K. Patient-administered Screening Tool May improve detection and diagnosis of Depression among adolescents. Clin. Pediatr (Phila). 57, 457-460 (2018).

Poole, L. A. et al. A Multi-family Group intervention for adolescent depression: the BEST MOOD program. Fam Process. 56, 317-330 (2017).

Yu, Y. et al. The role of Family Environment in depressive symptoms among University students: a large Sample Survey in China. PLoS One. 10, e0143612 (2015).

Rethorst, C. D. et al. Effects of depression, metabolic syndrome, and cardiorespiratory fitness on mortality: results from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Med. 47, 2414-2420 (2017).

Dai, L. et al. Influence of soil properties, topography, and land cover on soil organic carbon and total nitrogen concentration: a case study in Qinghai-Tibet plateau based on random forest regression and structural equation modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153440 (2022).

Smarr, K. L. & Keefer, A. L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for epidemiologic studies Depression Scale (CES-D), geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 63 (Suppl 11), S454-466 (2011).

Blodgett, J. M. et al. A systematic review of the latent structure of the Center for epidemiologic studies Depression Scale (CES-D) amongst adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 21, 197 (2021).

Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., Roberts, R. E. & Allen, N. B. Center for epidemiologic studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol. Aging. 12, 277-287 (1997).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381-1395 (2003).

Shatte, A., Hutchinson, D. M. & Teague, S. J. Machine learning in mental health: a scoping review of methods and applications. Psychol. Med. 49, 1426-1448 (2019).

Lee, Y. et al. Applications of machine learning algorithms to predict therapeutic outcomes in depression: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 241, 519-532 (2018).

Huang, Y. et al. Comparison of three machine learning models to predict suicidal ideation and depression among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 319, 221-228 (2022).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest-non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 28, 112-118 (2012).

Radloff, The, L. S. & Scale, C. E. S. D. A self-report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385-401 (1977).

Li, J. Y. et al. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in China: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 7459-7470 (2019).

Lu, J. et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet PsychiatryThe Lancet Psychiatry. 8, 981-990 (2021).

Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A. & Rohde, L. A. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 56, 345-365 (2015).

Sund, A. M., Larsson, B. & Wichstrøm, L. Role of physical and sedentary activities in the development of depressive symptoms in early adolescence. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 46, 431-441 (2011).

Mammen, G. & Faulkner, G. Physical activity and the Prevention of Depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 45, 649-657 (2013).

da Costa, B., Chaput, J. P., Lopes, M., Malheiros, L. & Silva, K. S. Movement behaviors and their association with depressive symptoms in Brazilian adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J. Sport Health Sci. 11, 252-259 (2022).

Oh, S., You, J. & Kim, Y. W. Physical fitness for depression in adolescents and adults: a Meta-analysis. Iran. J. Public. Health. 51, 2425-2434 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Physical activity and Mental Health among Chinese adolescents. Am. J. Health Behav. 45, 309-322 (2021).

Dong, X. et al. Physical activity, screen-based sedentary behavior and physical fitness in Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Front. Pediatr. 9, 722079 (2021).

Shin, M. S., Park, S. S., Lee, J. M., Kim, T. W. & Kim, Y. P. Treadmill exercise improves depression-like symptoms by enhancing serotonergic function through upregulation of 5-HT(1A) expression in the olfactory bulbectomized rats. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 13, 36-42 (2017).

Xia, M., Hao, J. Y. & W. X. L. & Dietary characteristics of patients with depressive and anxiety states. Chin. J. Mental Health. 25, 594-599 (2011).

Mei, S. L. Et, a. A survey on breakfast habits and the relationship with BMI and negative emotions among college students in a university in Changchun. Med. Soc. 30, 60-62 (2017).

Fouad, A. M. et al. Tryptophan in poultry nutrition: impacts and mechanisms of action. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 105, 1146-1153 (2021).

Knüppel, A., Shipley, M. J., Llewellyn, C. H. & Brunner, E. J. Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Sci. Rep. 7, 6287 (2017).

Hu, D., Cheng, L. & Jiang, W. Sugar-sweetened beverages consumption and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Affect. Disord. 245, 348-355 (2019).

Maras, D. et al. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev. Med. 73, 133-138 (2015).

Wang, X., Li, Y. & Fan, H. The associations between screen time-based sedentary behavior and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health. 19, 1524 (2019).

Paulich, K. N., Ross, J. M., Lessem, J. M. & Hewitt, J. K. Screen time and early adolescent mental health, academic, and social outcomes in 9- and 10- year old children: utilizing the adolescent brain Cognitive Development ℠ (ABCD) study. PLoS One. 16, e0256591 (2021).

Barthorpe, A., Winstone, L., Mars, B. & Moran, P. Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? A time use diary study. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 864-870 (2020).

Raniti, M. B. et al. Sleep duration and sleep quality: associations with depressive symptoms across adolescence. Behav. Sleep. Med. 15, 198-215 (2017).

Dağ, B. & Kutlu, F. Y. The relationship between sleep quality and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 47, 721-727 (2017).

Hamann, C., Rusterholz, T., Studer, M., Kaess, M. & Tarokh, L. Association between depressive symptoms and sleep neurophysiology in early adolescence. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 60, 1334-1342 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 45, 5-32 (2001).

Funding

This research was funded by the Shandong Provincial Social Science Planning Research Project [18CTYJ13 to Enqi Li] and the Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [23YJC890007 to Lijie Ding].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: L. Ding, E. Li.Analysis and interpretation of data: L. Ding, Z Wu, Q Wu. Drafting of the manuscript: L. Ding, R Wei. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.Study supervision: L. Ding, E. Li.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Sport University (2022018) and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, L., Wu, Z., Wu, Q. et al. Prevalence and lifestyle determinants of depressive symptoms among Chinese children and adolescents. Sci Rep 14, 27313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78436-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78436-w