Abstract

We used nationally representative data from the first wave of the Global Flourishing Study (N = 202,898) to (1) explore the distribution of forgivingness in 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries and (2) identify potential differences in dispositional forgivingness across nine sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, employment status, years of education, immigration status, frequency of religious service attendance, religious affiliation, racial/ethnic identity). Our descriptive analysis supported substantial cross-national variation in the proportion of people who endorsed ‘often/always’ forgiving others, ranging from .41 (Türkiye) to .92 (Nigeria). We estimated country-level descriptive statistics for forgivingness in each sociodemographic category, and then performed a series of random effects meta-analyses to aggregate results across countries. Meta-analytic results provided evidence of subgroup differences in forgivingness for religious service attendance and (to a lesser extent) age, with the highest forgivingness observed among people who attended religious services more than once a week and those 80 years or older. However, sociodemographic differences in forgivingness varied considerably across countries, including for those sociodemographic variables that did not show clear evidence of subgroup differences when country-specific estimates were pooled. Our findings lay the foundation for population-level assessment of forgiveness over time and public health strategies to promote forgiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As social beings, all people are hurt, wronged, or offended by others at one time or another. Interpersonal transgressions are perceived injustices that, if not adequately dealt with, can sometimes lead to unforgiveness, which is a complex cognitive-emotional experience consisting of bitterness, resentment, hostility, hate, anger, and fear accompanied by vengeful and avoidant motives1. In the stress-and-coping theory of forgiveness, a person may use various methods to reduce their unforgiveness (e.g., excusing the transgressor’s behavior, seeking revenge, turning the situation over to God), one of which is to forgive the transgressor2. Although definitions vary, social scientists generally agree that forgiveness involves a prosocial change in one’s feelings, motivations, thoughts, and behavioral intentions toward a transgressor3. A corpus of evidence suggests that forgiveness is related to better wellbeing across mental (e.g., fewer depression symptoms), social (e.g., stronger sense of relatedness to others), physical (e.g., lower cardiovascular stress), and religious/spiritual (e.g., stronger connection with the sacred) dimensions of health and wellbeing4,5,6,7. As important as it is to forgive a single transgression, health and wellbeing are most positively affected when people are able to practice forgiveness consistently. Such generalization of forgiveness across time and situations is dispositional forgivingness8.

When the health and wellbeing benefits of forgiveness are considered alongside how common it is to be hurt or wronged by others, the public health implications of forgiveness may be quite substantial9. Applying a public health lens to forgiveness, studies have recently shown that forgiveness can be promoted in communities through scalable self-directed interventions10 and campaigns aimed at increasing knowledge of forgiveness, providing resources to promote forgiveness, and motivating people to use resources to forgive11. However, an essential part of being able to target and address public health issues effectively is population-level assessment and monitoring, which can inform policy decisions and guide the implementation and specificity of interventions to support subpopulations that may be vulnerable to adverse health and wellbeing outcomes12.

Some prior research has used multinational data to describe forgiveness globally13,14. For example, in one cross-sectional study with a convenience sample of more than 1 million individuals from 75 nations, McGrath13 explored cross-national similarities and differences in the tendency to forgive others. Mean forgivingness scores were quite similar in many of the countries, although more considerable differences emerged between some countries (with a range from 1 to 5, lowest mean of 3.39 in Japan and North Korea vs. highest mean of 4.11 in Paraguay). While these findings have played an important role in strengthening our understanding of forgiveness around the world, the generalizability of this evidence is limited because the data are based on country-level convenience (and sometimes very small) samples collected over several years. To our knowledge, no prior study has collected nationally representative population-level data on forgiveness or forgivingness in multiple countries. The Global Flourishing Study (GFS), an intended five-year longitudinal cohort study with nationally representative samples from 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries, provides a unique opportunity to measure and track population-level forgivingness in different parts of the world. In the present study, we use the first wave of GFS data to explore the distribution and potential sociodemographic differences in forgivingness.

Sociocultural variation in forgivingness

Although forgiveness is widely recognized as an intrapersonal process that occurs internally, forgiveness is often influenced by the broader sociocultural context in which a person is embedded15,16,17. Applying a socioecological life course lens18, forgivingness (the tendency to forgive across time and situations) is shaped over time by a network of hierarchically nested and interrelated socioecological layers ranging from those that are more proximal and directly influential to those that are more distal and indirectly influential19. For example, a highly proximal layer is the familial context (e.g., family structure, parent-child relationships). As one example, parents may support the development of a disposition to forgive among their children by modeling forgiveness or prescribing forgiveness when their children experience interpersonal hurts20. A somewhat less proximal layer is the social context in which a person grows up (e.g., experiences within school settings or religious communities). For instance, research has shown that forgiveness education curricula implemented with school-going children have the potential to increase knowledge of forgiveness, state forgiveness for a specific transgression, and a willingness to apply forgiveness to interpersonal hurts in the future21,22. Similarly, religious communities provide young people with opportunities to learn about and internalize the value of forgiveness as a moral virtue by exposing them to key religious figures who modeled forgiveness23.

Expanding out further, the development of a disposition to forgive others might be indirectly influenced by the shared lived experiences of people within a society. For example, in societies that have experienced a long history of civil conflict, the climate of trauma may constrain forgivingness in the population24. On the other hand, a post-conflict society may provide fertile ground for younger generations to develop a forgiving disposition if they witness and learn how to practice forgiveness as the society transitions to a more peaceful state25. Perhaps even more distally, cultural values concerning forgiveness can indirectly influence forgivingness19. Most attention to cultural differences in forgivingness has been devoted to the broad dimension of individualism vs. collectivism. However, more subtle cultural dimensions (e.g., harmonious value) may be even more important for differentiating between the disposition to forgive among people from diverse cultures26. While forgivingness-relevant factors embedded within socioecological layers that are most proximal to the individual will often be particular to that person (e.g., the perpetrator of the transgression), factors within the most distal layers are more likely to be common to many people within a society (e.g., normative customs or practices related to forgiveness). To the extent that forgivingness-promoting and unforgiveness-inhibiting factors exist at distal layers of a country’s sociocultural ecosystem, we might expect the population-level prevalence of forgivingness to be higher.

To date, the research around the world on forgivingness is scattered and non-systematic, informed mostly by single-shot studies of varying quality and different local samples that are rarely representative of the general population (for a review of forgivingness and culture, see Sandage et al.26; for reviews by geographical region, see Ho27 for East Asia; Mullet & Neto28 for the Arab region; Rique et al.29 for South America and Spanish speaking Europe; Worthington et al.30 for Africa). In the absence of prior cross-national research on forgivingness with nationally representative samples, here we consider the possibility that forgivingness might vary around the world because some aspects of life that are prone to incite people to unforgiveness might differ. For example, indicators of social and interpersonal discord might differ cross-nationally, suggesting that there could be differences in opportunities to forgive or not to forgive. Those indicators might interact with other factors, such as culture (e.g., orientation toward collectivism vs. individualism) or resources to make coping easier (e.g., socioeconomic status), to impact forgivingness.

We briefly illustrate some of these dynamics using a non-exhaustive set of national-level and individual-level forgiveness-relevant metrics for the countries included in this study (see Table 1). India, Nigeria, and Türkiye were the only three countries that ranked among the bottom three (most negative) on at least one indicator of social discord (i.e., history of conflict index) and one indicator of interpersonal discord (i.e., being assaulted or experiencing anger). When contrasted with Australia, which ranked among the top three (most positive) countries on at least one indicator of social and interpersonal discord, these metrics suggest that opportunities to practice forgiveness may be greater in some countries than others. However, discord is likely to interact with other sociocultural factors to influence forgivingness at the population level. For instance, Nigeria ranked among the top three countries on collectivism, and it is possible that their cultural orientation of valuing reconciliation and maintaining social harmony within the country might influence Nigerians to pursue forgiveness as a normative response to injustices despite the comparatively high levels of social and interpersonal discord. Hence, complex interactions between different factors within the unique sociocultural landscape of each country might contribute to cross-national variability in propensities to have dispositional forgivingness.

Sociodemographic differences in forgivingness

Effective public health promotion relies on empirical evidence about subpopulations that might benefit from greater protective resources for health promotion, because these insights can inform decisions about how best to allocate resources to support population wellbeing38. Similarly, a public health agenda to promote forgiveness needs to be informed by research that aims to identify disparities among different sociodemographic groups (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity) and monitors progress toward reducing such disparities.

Some prior research has sought to determine what kinds of sociodemographic differences in forgivingness might exist. One sociodemographic variable that has been investigated widely is gender. Miller et al.39 meta-analyzed 39 studies that reported on gender differences in dispositional forgivingness. They found that women tended to rate themselves as more forgiving than men, although almost all of the studies that were included used samples from the United States (more than half of which were college students). Thus, our understanding of gender differences in forgivingness in the global population is limited.

Many studies have also reported on the association between age and forgivingness. Most findings suggest that older individuals tend to report higher forgivingness than those who are younger40,41,42. Much of the prior research on age differences in forgivingness is also based on nonrepresentative samples drawn from Western countries (particularly the United States). Thus, it remains unclear whether available evidence can be generalized worldwide.

Religious/spiritual engagement is another sociodemographic factor that has been examined frequently. Davis et al.4 meta-analyzed 64 studies that reported associations between eight broad indicators of religion/spirituality (e.g., religious commitment, spirituality) and forgivingness. All indicators were positively related to forgivingness. Similar findings have been reported in studies that have focused on particular aspects of religious/spiritual engagement, such as frequency of religious service attendance43. While the empirical evidence generally supports earlier theorizing about the role of religious/spiritual engagement in promoting forgiveness44, existing knowledge in this area generally comes from Christian-majority convenience samples living in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) countries.

Other sociodemographic factors (e.g., education, marital status, employment, immigration) have received less attention in empirical research on forgivingness, with somewhat mixed findings. For example, some studies have reported a positive association between educational attainment and forgivingness42, whereas others have reported a null association41. Similarly, some research points to lower forgivingness among people who have never been married40, while other studies have found little evidence of differences in forgivingness as a function of marital status42. These findings suggest that additional research is needed across a broad spectrum of countries to improve our understanding of potential differences in forgivingness on sociodemographic factors for which evidence is more equivocal at present.

Taken together, previous research points to some potential sociodemographic disparities in forgivingness. However, the existing body of evidence is larger and more consistent for some sociodemographic factors (e.g., gender) than others (e.g., education). In addition, methodological differences (e.g., sample variation across studies conducted in different countries) can make it challenging to directly compare findings from prior studies, particularly for sociodemographic factors that have been examined less frequently. Moreover, most studies along these lines have worked with non-representative samples (e.g., college students) from WEIRD countries, particularly the United States. Much less is known about sociodemographic differences in forgivingness among populations living in less WEIRD contexts, and it remains unclear whether existing research is generalizable to the global population. To support a global public health agenda focused on promoting forgiveness at the population level, research exploring sociodemographic differences in forgiveness is needed with representative samples from diverse geographic and cultural contexts around the world.

The present study

This preregistered study uses nationally representative data from 22 countries included in Wave 1 of the GFS to explore the distribution of forgivingness in each country and test for potential sociodemographic differences in forgivingness. As a preliminary step, we describe the distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics that were assessed consistently across the countries (i.e., age, gender, marital status, employment status, years of education, immigration status, frequency of religious service attendance). Although not a central part of our purpose for exploring the distribution of forgivingness in each country, we nonetheless anticipated that forgivingness would show some meaningful cross-national variation. Based on prior empirical evidence, we expected that forgivingness across all countries would exhibit variations based on sociodemographic characteristics. While our principal emphasis is on potential sociodemographic differences in forgivingness across all countries, we also anticipated some cross-national variation in sociodemographic differences because of the unique sociocultural climate of each country.

Methods

Methodological details described below have been adapted from VanderWeele et al.45. Further methodological information is available elsewhere46,47,48,49,50,51. The GFS was ruled exempt by the Baylor University Institutional Review Board (#1841317-2). Institutional Review Board approval for all data collection activities was obtained by Gallup Inc. Data collection activities were performed in accordance with relevant ethical regulations, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All personally identifiable information was removed from the data used in the present study by Gallup Inc.

Study sample

Wave 1 of the GFS included nationally representative samples from 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Egypt, Germany, Hong Kong (Special Administrative Region of China), India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tanzania, Türkiye, the United Kingdom, and the United States (N = 202,898). The countries were selected to (1) maximize coverage of the world’s population, (2) ensure geographic, cultural, and religious diversity, and (3) prioritize feasibility in line with existing data collection infrastructure. Data collection was conducted by Gallup Inc. Data for Wave 1 was collected primarily during 2023, although some countries began data collection in 2022 and exact dates of data collection varied to some extent by country51. The precise sampling design that was used to ensure samples were nationally representative varied by country50,51. The GFS survey centers on salient aspects of wellbeing, such as happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships, and financial stability52, along with other sociodemographic, social, economic, political, religious, personality, childhood, community, health, and wellbeing variables. Gallup Inc. translated the GFS survey into multiple languages following the TRAPD (translation, review, adjudication, pretesting, and documentation) model for cross-cultural survey research50.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables

Seven sociodemographic variables were assessed consistently across the 22 countries: age, gender, marital status, employment status, education status, frequency of religious service attendance, and immigration status. Continuous age was classified into 18–24, 25–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80 or older age categories. Gender was assessed as male, female, or other. Marital status was assessed as single/never married, married, separated, divorced, widowed, and domestic partner. Employment was assessed as employed for an employer, self-employed, retired, student, homemaker, unemployed and looking for a job, and none of these/other. Education was assessed as up to 8 years, 9–15 years, and 16 or more years. Frequency of religious service attendance was assessed as more than once a week, once a week, one-to-three times a month, a few times a year, or never. Immigration status was dichotomously assessed with an item that asked participants to report whether they had been born in the country where data collection was taking place.

Religious affiliation was also assessed in all countries, but there were considerable cross-country differences in the response categories that were endorsed by participants because some religious affiliations are only applicable in certain countries and not others. Religious affiliation response category options included Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Sikhism, Baha’i, Jainism, Shinto, Taoism, Confucianism, Primal/animist/folk religion, Spiritism, Umbanda, Candomblé, and other African-derived religions, Chinese folk/traditional religion, some other religion, or no religion/atheist/agnostic. Racial/ethnic identity was assessed in most (18/22) countries, and response categories varied across countries. Additional details about measurement of the sociodemographic variables can be found in the GFS Codebook (https://osf.io/cg76b).

Outcome variable

Forgivingness was assessed with the following question that was adapted from the widely used Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality53: “How often have you forgiven those who have hurt you?”46,48. Response options were ‘Always,’ ‘Often,’ ‘Rarely,’ and ‘Never.’ Consistent with our preregistered analytic plan, we dichotomized this variable into (0) never/rarely and (1) often/always.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R 4.2.254. Descriptive statistics for the full sample, weighted to be nationally representative within each country, were estimated for each of the sociodemographic variables. Nationally representative proportions and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for people endorsing ‘often/always’ forgiving others were estimated separately for each country and ordered from highest to lowest. As a post-hoc secondary analysis, we replicated this analysis after dichotomizing the outcome variable into categories of (0) never/rarely/often and (1) always.

Variation in proportions of ‘often/always’ forgiving others across sociodemographic categories were estimated by country. Primary results consisted of random effects meta-analyses of the country-specific proportions for ‘often/always’ forgiving others in each specific sociodemographic category55,56, along with 95% confidence intervals, standard errors, lower and upper limits of a 95% prediction interval across countries, heterogeneity (τ, back-transformed from the logit-scale), and I2 for evidence of variation within a particular sociodemographic variable across countries57. The metafor package was used to conduct all meta-analyses58. Within each country, we conducted a global test of variation in forgivingness across categories of each particular sociodemographic variable. A pooled p-value across countries was used to test whether forgivingness differs among categories of a particular sociodemographic variable in at least one country59. We provide Bonferroni corrected p-value thresholds based on the seven sociodemographic variables (i.e., age, gender, marital status, employment status, education status, frequency of religious service attendance, and immigration status) that were included in the meta-analyses: p = .05/7 = .00760. Religious affiliation and racial/ethnic identity were not part of the meta-analyses because these variables were not measured consistently across all 22 countries. As a supplementary analysis, we conducted population weighted meta-analyses for the same sociodemographic variables included in the random effects meta-analyses.

Missing data

Missing data on all sociodemographic and outcome variables were imputed using multivariate imputation by chained equations, with five imputed datasets produced61,62. To account for variation in the assessment of certain variables across countries (e.g., racial/ethnic identity), the imputation process was conducted separately in each country. This within-country imputation approach ensured that the imputation models accurately reflected country-specific contexts and assessment methods. Including the sampling weight in the multiple imputation procedure allowed missingness to be related to the probability of inclusion in the study.

Accounting for complex sampling design

Wave 1 of the GFS used different sampling schemes across countries based on availability of existing panels and recruitment needs51. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design components by including weights, primary sampling units, and strata. Additional methodological details, including the approach that was used to account for the complex sampling design, can be found elsewhere49.

Results

In Table 2, we present the sociodemographic characteristics of the total sample. Country-specific samples were largest in the United States (19%), Japan (10%), and Sweden (7.4%), whereas the smallest samples were from Türkiye (0.7%), South Africa (1.3%), and Hong Kong (1.5%). The largest age group consisted of those aged 30–39 (20%), followed by those aged 40–49 (17%) and 50–59 (16%). The gender distribution was roughly equal across males (49%) and females (51%). A majority of people were married (53%), were either employed by an employer (39%) or self-employed (18%), had completed 9–15 years of education (57%), and were born in the country where data was collected (94%). Religious service attendance varied from people who attended at least once a week (19%) or more often (13%) to those who never attended (37%).

Tables S1a to S22a contain sociodemographic characteristics for each country. Countries have somewhat unique sociodemographic profiles. For example, compared to Nigeria, Australia has a considerably larger share of people who are 60 years or older (33% vs. 7%), are employed for an employer (49% vs. 10%), have completed 9 or more years of education (98% vs. 62%), were born in another country (23% vs. < 1%), and are not affiliated with a religious tradition (53% vs. < 1%), highlighting variability in the sociodemographic compositions of the countries.

Distribution of forgivingness

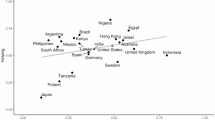

In Table 3, we order the countries based on the proportion of people who reported ‘often/always’ forgiving others. Countries with the highest proportion of forgivingness were Nigeria (0.92, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.93), Egypt (0.87, 95% CI: 0.86, 0.88), and Indonesia (0.85, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.86), while those with the lowest were Türkiye (0.41, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.44), Japan (0.57, 95% CI: 0.56, 0.58), and Hong Kong (0.62, 95% CI: 0.60, 0.65). These results provide evidence of meaningful variation in forgivingness across different countries. When we estimated the proportion of individuals who endorsed ‘always’ forgiving others in each country (see Table S23), relative rankings for most countries were similar to Table 3 (9/22 countries differed by two or fewer positions). However, relative rankings for some countries differed more substantially; the countries that evidenced the largest upward (more positive) shift in relative ranking were India (13th to 2nd), the Philippines (16th to 7th), and Türkiye (22nd to 14th), whereas the countries with the largest downward (more negative) shift in relative ranking were Australia (7th to 19th), Sweden (11th to 21st), and Germany (12th to 20th).

Sociodemographic differences in forgivingness

In Table 4, we report the results of the random effects meta-analyses. When estimated proportions of forgivingness for each country were pooled, frequency of religious services attendance was monotonically associated with higher forgivingness. Examination of the 95% CIs for the proportions supported robust differences in forgivingness between two or more categories of religious service attendance, with the largest difference found between people who reported attending weekly or more often (0.87, 95% CI: 0.83, 0.90) and those who never attended (0.69, 95% CI: 0.65, 0.74). Higher age was also monotonically associated with higher forgivingness, but evidence of differences in proportions across age groups was more marginal; the largest difference was between the 18–24 (0.73, 95% CI: 0.67, 0.77) and 80 or older (0.87, 95% CI: 0.77, 0.94) age categories. The meta-analytic results did not provide as notable evidence of differences in forgivingness across gender, marital status, employment status, years of education, or immigration status categories when the results for all 22 countries were pooled.

Tau (τ) values in Table 4 estimate cross-country variation in forgivingness for each of the sociodemographic categories. There was some evidence of cross-national heterogeneity in forgivingness for all sociodemographic categories, although variation was greater for some categories than others. For example, tau was larger for the 80 or older age category (0.20) compared to the other age categories (0.08–0.12), pointing to greater cross-national variability in forgivingness for this age category relative to the others.

Each of the global p-values in Table 4 passed the Bonferroni-corrected threshold, indicating that there was evidence of differences in forgivingness for each sociodemographic variable in at least one country. Country-specific results for sociodemographic differences in forgivingness are reported in Tables S1b-S22b, with accompanying forest plots providing a visual display of country-specific forgivingness for each sociodemographic category (see Figures S1-S34). We did not find support for a universal pattern that applied across all countries for sociodemographic differences in forgivingness, including the sociodemographic characteristics for which there was evidence of group differences in the random effects meta-analyses. For example, meta-analytic results in Table 4 indicated that the proportion endorsing ‘often/always’ forgiving others was highest among people who attended religious services more than once a week, but this was not the case in some countries (e.g., Egypt, Spain).

There were country-specific instances in which we found evidence of differences in forgivingness between sociodemographic categories that did not show clear evidence of differences when pooled across all countries in the random effects meta-analyses. For example, results in Table 4 show similar proportions of forgivingness among females and males when averaged across the 22 countries, but in Argentina there was evidence supporting higher forgivingness among females compared to males (Table S1b). Consistent with the tau estimates in Table 4, we observed cross-country variation in the differences in forgivingness between some of the sociodemographic categories. For instance, forgivingness was considerably higher among people who attended religious services more than once a week compared to those who never attended in Brazil (Table S3b) and the United Kingdom (Table S21b), but there was little evidence of a difference in forgivingness between these two categories in Egypt (Table S4b) and Türkiye (Table S20b).

We also estimated country-specific variation in forgivingness as a function of religious affiliation and racial/ethnic identity (when available), but those variables were not part of the meta-analysis because of the use of locally meaningful categories or substantial variation in observed categories for each country (see Tables S1b-S22b). Results provided some evidence of differences in forgivingness by categories of these sociodemographic variables in certain countries, such as a higher forgivingness among adherents of Christianity compared to the Islam, Buddhism, and no religion/atheist/agnostic categories in Sweden (Table S18b); as well as among those who self-identify racially/ethnically as White compared to those who identify as Asian, Black, or Hispanic in the United States (Table S22b).

When we repeated the meta-analyses using a population weighted approach in which each country’s results was weighted according to its population size in 2023 (see Table S24), the pattern of results for sociodemographic variation in forgivingness across the countries was similar to what was found for the random effects meta-analyses. To illustrate, both approaches suggested that higher age and greater frequency of religious service attendance are monotonically associated with higher forgivingness. However, some differences were observed between the results of the two meta-analytic approaches. As one example, there was clearer evidence of a difference between the 18–24 and 80 or older age categories when the population weighted analytic approach was applied.

Discussion

Leveraging multinational data from Wave 1 of the GFS, this study explored the distribution of forgivingness in 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries and tested for potential sociodemographic differences in the proportion of people who endorsed ‘often/always’ forgiving others. We observed three main findings, including some evidence of (1) cross-national variation in forgivingness, (2) sociodemographic differences in forgivingness across countries, and (3) cross-national variation in sociodemographic differences in forgivingness.

Distribution of forgivingness

Although we were principally interested in documenting evidence of forgivingness in each country, our findings align with previous studies that have reported heterogeneity in country-level estimates of forgivingness13,14. When comparing the relative rankings concerning ‘often/always’ forgiving others for the 21 countries that were included both in our analysis and McGrath’s13 75-nation study, relative rankings for some countries were quite similar across the two studies. For example, Nigeria was positioned 1st in both sets of results, while Japan was positioned lowest in McGrath13 and second lowest in our analysis. However, some findings diverged from those observed in McGrath13, including considerably higher relative ranking positions for some countries in the present study (e.g., 2nd vs. 14th for Egypt) and lower relative ranking positions for other countries (e.g., 17th vs. 7th for Brazil). These differences may be due to several methodological factors, such as differences in sampling strategies (e.g., representative vs. non-representative samples), measurement approaches (e.g., single item vs. multi-item assessment of forgivingness), and timing of data collection (e.g., 2022–2024 vs. 2002–2012). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to leverage multinational data collected within a relatively short window of time (approximately 2 years compared to 10 years in McGrath13) to provide nationally representative benchmarks of forgivingness in 22 countries. As subsequent waves of data collection for the GFS are completed, such benchmarking could be used to evaluate population-level changes in forgivingness that local policymakers and public health experts might draw on in their efforts to promote forgiveness.

The cross-country variation in forgivingness that we observed may be due to several possibilities, including differences in population demographics (e.g., some countries have younger populations than others) and sociocultural factors that may play a salient role in shaping dispositional forgivingness or reasonably give rise to differences in forgivingness across countries. For instance, consider the proportions of people who endorsed ‘often/always’ forgiving others in Kenya (.85, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.86) and Japan (.57, 95% CI: 0.56, 0.58) in light of the national- and individual-level forgiveness-relevant metrics reported in Table 1. Japan had considerably better rankings on 5/6 social (e.g., history of conflict index) and interpersonal discord (e.g., percentage assaulted in the last 12 months) metrics, but Kenya is more collectivistic than Japan. It may be that Kenyans are generally more likely than their Japanese counterparts to encounter situations that provide an opportunity for people to practice forgiveness (e.g., interpersonal conflict), and that when such situations arise collectivistic cultural norms in Kenya might lead them to pursue forgiveness in service of restoring and maintaining social harmony.

While sociocultural factors likely have some role in contributing to cross-country variation (or lack thereof) in forgivingness, methodological factors ought to be considered as well. For example, cross-country variation in forgivingness may have been affected by cross-cultural differences in how people interpreted or responded to the forgivingness item, as well as potential seasonal effects because the timing of data collection for the GFS differed across countries50,63,64. However, based on the cognitive interviews that were performed during the survey development phase of the GFS, the original forgivingness item taken from the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (i.e., “I have forgiven those who hurt me”) was modified slightly to the version used in this study and certain response options were adjusted for improved clarity (e.g., use of ‘Rarely’ instead of ‘Seldom’), which can help mitigate method effects65. Nonetheless, these methodological considerations draw attention to the complexities that arise when conducting cross-national research and highlight the importance of exercising some caution when using the findings of this study to make cross-country comparisons in forgivingness.

Sociodemographic differences in forgivingness

Results from the random effects meta-analyses provided evidence (through examination of 95% CIs for proportions) of differences in forgivingness across the 22 countries as a function of religious service attendance and (to a lesser extent) age. Specifically, we found that forgivingness was highest among people who attended religious services more than once a week (and was lowest among those who never attended) and the 80 or older age group (and was lowest among the 18-24-year-old group). These findings correspond with previous research that has shown forgivingness is positively associated with religious participation4,44 and age40,41.

The meta-analyses provided more limited evidence of group differences in forgivingness for any of the other sociodemographic characteristics that were examined when estimates were pooled across countries. Although existing research on many of these sociodemographic characteristics is limited and has yielded mixed findings (e.g., education, employment), our findings contrasted a prior meta-analysis that suggested females tend to rate themselves as more forgiving than males39. Several methodological factors (e.g., sample variation, measurement differences) could explain why this finding for gender diverges from past work, and it is also worth noting that there were country-specific results supporting higher forgivingness among females compared to males (e.g., Japan, Poland).

Evaluating the country-specific results for sociodemographic variation in forgivingness, the category for each sociodemographic characteristic with the highest forgivingness (regardless of whether 95% CIs for proportions of forgivingness in the subgroups were overlapping) in the most number of countries was the 80 years or older age group in 13 countries (lowest among the 18–24 age group in seven countries); females vis-à-vis males in 12 countries; those who are widowed in 16 countries (lowest among those who are single and have never been married in 10 countries); those who are retired in 11 countries (lowest among those who are unemployed and looking for a job in eight countries); those who attend religious services more than once a week in 18 countries (lowest among those who never attend in 19 countries); those with 16 or more years of education in 15 countries (lowest among those with 8 years of education or less in 11 countries); and those who were born outside the country where data collection took place in 11 countries. However, there was considerable cross-country variation in the magnitude of the differences in forgivingness that were observed for each sociodemographic characteristic. For example, in the 16 countries where forgivingness was highest among people who are widowed, the difference between this group and those who are single and have never been married ranged from somewhat negligible in some countries (e.g., Australia, Germany) to quite substantial in others (e.g., Brazil, Egypt). There were also instances in which the sociodemographic categories with the highest forgivingness in most countries had the lowest forgivingness in certain countries, although 95% CIs for proportions of forgivingness mostly overlapped across subgroups. As one illustration, forgivingness was lowest among those in the 80 years or older age group in three countries (i.e., Argentina, Egypt, Nigeria), but in each case there were overlapping 95% CIs for this age category and the age category that had the highest forgivingness in the respective country. While more fine-grained analyses are required to explore and understand the potential reasons for cross-national variation in sociodemographic differences that were observed in this study, our findings align with the notion that forgiveness is shaped by features of the sociocultural environment in which a person is situated19,26.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is the use of large samples that were weighted to be nationally representative, allowing us to estimate the distribution of forgivingness in multiple countries and identify subpopulations (both within and across countries) that may be especially likely to benefit from interventions to promote forgiveness. By estimating forgivingness in different countries around the world, both at national and subpopulation levels, our findings set the stage for developing a more focused public health agenda oriented toward the promotion of forgiveness. Despite the strengths of this study, there are methodological limitations that warrant consideration. First, forgivingness was assessed with a single item. Although this approach is not uncommon in large-scale epidemiologic studies such as the GFS, our conceptual coverage of the disposition to forgive others is limited by the use of a single item. The findings of this study could be complemented by additional evidence drawing on measures (e.g., Trait Forgivingness Scale) that can provide more fine-grained conceptual coverage of dispositional forgivingness66. Second, the first wave of the GFS includes 22 countries that collectively provide a geographically and culturally diverse multinational sample. While Wave 1 of the GFS is representative of approximately half of the global human population, many diverse cultures and contexts may not be represented in the GFS. Given the heterogeneity that we observed across countries, additional work is needed to determine whether our findings generalize to countries that were not included in this study. Third, we applied a descriptive analytic approach using cross-sectional data. Although we drew on some sociocultural indicators to contextualize our findings, future studies could build on this study through predictive analyses that explore how a combination of different national-level indicators might account for cross-national variation in forgivingness among countries included in the GFS. For instance, we considered one broad dimension of culture (i.e., collectivism vs. individualism) articulated in Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory67 as a possible explanation for cross-national variation in forgivingness, but other cultural dimensions (e.g., short-term vs. long-term orientation) could also be important for understanding differences in forgivingness across countries19. Moreover, our descriptive exploration of sociodemographic differences in forgivingness should not be interpreted as implying causality. As one example, results of the random effects meta-analysis indicated that forgivingness was highest among people who attended religious services more than once a week, but this could be because religious service attendance promotes the practice of forgiveness or because those who tend to be more forgiving of others are inclined to attend religious services with greater regularity than those who are less likely to practice forgiveness consistently. Further exploration of these causal questions will be possible as subsequent waves of the GFS become available.

Conclusion

In summary, this multinational study documented evidence concerning the distribution of forgivingness in 22 countries and sociodemographic variation in forgivingness both within and across countries. By providing an initial set of forgivingness benchmarks for a wide range of countries and various sociodemographic characteristics, this study may serve as a useful resource for policymakers, practitioners, and scientists interested in understanding and promoting forgiveness. As the GFS cohort is established through subsequent years of data collection, the panel data will provide a valuable opportunity to track changes in forgivingness over time (both at the population level and within specific subpopulations). Such evidence will be important for developing public health strategies and policies oriented toward the promotion of forgiveness within different populations, monitoring progress against targets, and making well-informed decisions about modifications that may be needed to improve the effectiveness of public health efforts to promote forgiveness.

Data availability

Wave 1 Global Flourishing Study data are publicly available through the Center for Open Science (https://www.cos.io/gfs). The research questions, variables, and analytic plan for the current study were preregistered with the Center for Open Science prior to accessing data (https://osf.io/zugyn). All code to reproduce analyses are openly available in an online repository68.

References

Wade, N. G. & Worthington, E. L. Jr. Overcoming interpersonal offenses: Is forgiveness the only way to deal with unforgiveness? J. Couns. Dev. 81, 343–353 (2003).

Strelan, P. The stress-and-coping model of forgiveness: Theory, research, and the potential of dyadic coping. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 63–73 (Routledge, 2020).

Toussaint, L., Worthington, E. L. Jr., Webb, J. R., Wilson, C. & Williams, D. R. Forgiveness in human flourishing. In Human Flourishing: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Neuroscience, Health, Organizations and Arts (eds Las Heras, M., Grau Grau, M. & Rofcanin, Y.) 117–131 (Springer, 2023).

Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L. Jr., Hook, J. N. & Hill, P. C. Research on religion/spirituality and forgiveness: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 5, 233–241 (2013).

Fehr, R., Gelfand, M. J. & Nag, M. The road to forgiveness: A meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychol. Bull. 136, 894–914 (2010).

Gao, F., Li, Y. & Bai, X. Forgiveness and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 186, 111350 (2022).

Rasmussen, K. R., Stackhouse, M., Boon, S. D., Comstock, K. & Ross, R. Meta-analytic connections between forgiveness and health: The moderating effects of forgiveness-related distinctions. Psychol. Health. 34, 515–534 (2019).

Cowden, R. G., Chen, Z. J., Bechara, A. O. & Worthington, E. L. Jr. Associations of dispositional forgivingness with facets of well-being among Colombian adults: A longitudinal outcome‐wide analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 58, 153–163 (2023).

VanderWeele, T. J. Is forgiveness a public health issue? Am. J. Public Health. 108, 189–190 (2018).

Ho, M. Y. et al. International REACH forgiveness intervention: A multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ Public Health. 2, e000072 (2024).

Bechara, A. O. et al. Do forgiveness campaign activities improve forgiveness, mental health, and flourishing? Int. J. Public Health. 69, Article1605341 (2024).

Mathers, C. D. et al. Population health metrics: Crucial inputs to the development of evidence for health policy. Popul. Health Metr. 1, Article 6 (2003).

McGrath, R. E. Character strengths in 75 nations: An update. J. Posit. Psychol. 10, 41–52 (2015).

Park, N., Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. Character strengths in fifty-four nations and the fifty US states. J. Posit. Psychol. 1, 118–129 (2006).

Griffin, B. J., Cowden, R. G. & Shawkey, L. Bibliography of narrative reviews and meta-analyses on forgiveness (2004–2018). In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 335–344 (Routledge, 2020).

Worthington, E. L. Jr. Understanding forgiveness of other people: Definitions, theories, and processes. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 11–21 (Routledge, 2020).

de Vries, W. et al. Forgiveness reconsidered: Agency and the contextual nature of forgiveness in the aftermath of clergy sex abuse. In International Handbook of Emotions – Resourceful Cultural Perspectives, Vol. 1 (eds Mayer, C.-H. & Vanderheiden, E.) (Springer, in press).

Tomlinson, M. et al. Optimising child and adolescent health and development through an integrated ecological life course approach. BMJ 372, m4784 (2021).

Cowden, R. G. Four key areas of interpersonal forgiveness research that have developed over the last three decades: A reflection and tribute to Everett L. Worthington, Jr. Spiritual. Clin. Pract. 11, 94–104 (2024).

van der Wal, R. C., Karremans, J. C. & Cillessen, A. H. N. Causes and consequences of children’s forgiveness. Child. Dev. Perspect. 11, 97–101 (2017).

Freedman, S. & Chen, E. Y. J. Forgiveness education as a form of peace education with fifth-grade students: A pilot study with implications for educators. Peace Confl. 29, 235–246 (2023).

Rapp, H., Wang Xu, J. & Enright, R. D. A meta-analysis of forgiveness education interventions’ effects on forgiveness and anger in children and adolescents. Child. Dev. 93, 1249–1269 (2022).

Komesuor, J. et al. Forgiveness among Ghanaian children and early adolescents in the context of peer-to-peer dyads. Pers. Relatsh. 30, 825–853 (2023).

Hanke, K. & Fischer, R. Socioeconomical and sociopolitical correlates of interpersonal forgiveness: A three-level meta-analysis of the Enright Forgiveness Inventory across 13 societies. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 514–526 (2013).

Bechara, A. O. et al. Adapting positively to trauma: Associations of posttraumatic growth, wisdom, and virtues in survivors of civil war. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma. 30, 1292–1306 (2021).

Sandage, S. J., Crabtree, S. A. & Bell, C. A. Forgiveness and culture: Conceptual issues. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 201–211 (Routledge, 2020).

Ho, M. Y. Forgiving in East Asian cultures: Theory and empirical research. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 234–241 (Routledge, 2020).

Mullet, E. & Neto, F. Forgiveness in the Arab World and in Central Africa. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 212–222 (Routledge, 2020).

Rique, J., de Abreu, E. L. & Klatt, J. Theories and empirical research on forgiveness in South America and Latin Europe: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Spain, and Portugal. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 242–252 (Routledge, 2020).

Worthington, E. L. Jr. et al. Forgiveness research in Africa: The present status and future prospects. In Handbook of Forgiveness 2nd Edn (eds Worthington, Jr., E. L. & Wade, N. G.) 223–233 (Routledge, 2020).

World Bank. Poverty and Inequality Platform (Version 20230919_2017_01_02_PROD). https://pip.worldbank.org/home (2024).

Institute for Economics & Peace. Public Release Data: Global Peace Index 2023. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/public-release-data/ (2023).

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Global Dashboard (Version 02/23/2024). https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard (2024).

World Bank. Health Nutrition and Population Statistics: Population Estimates and Projections (Version 12/20/2023). https://databank.worldbank.org/source/population-estimates-and-projections# (2023).

Pelham, B., Hardin, C., Murray, D., Shimizu, M. & Vandello, J. A truly global, non-WEIRD examination of collectivism: The Global Collectivism Index (GCI). Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 3, 100030 (2022).

Lomas, T., Padgett, R. N., Lai, A. Y., Pawelski, J. O. & VanderWeele, T. J. A multidimensional assessment of global flourishing: Differential rankings of 145 countries on 38 wellbeing indicators in the Gallup World Poll, with an accompanying principal components analyses of the structure of flourishing. J. Posit. Psychol. (2024). Advance online publication.

Lomas, T. et al. Complexifying individualism versus collectivism and west versus east: Exploring global diversity in perspectives on self and other in the Gallup World Poll. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 54, 61–89 (2023).

Brownson, R. C., Fielding, J. E. & Maylahn, C. M. Evidence-based public health: A fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 30, 175–201 (2009).

Miller, A. J., Worthington, E. L. Jr. & McDaniel, M. A. Gender and forgiveness: A meta-analytic review and research agenda. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 27, 843–876 (2008).

Cowden, R. G. et al. Development of the Collectivist-Sensitive Trait Forgivingness Scale. Scand. J. Psychol. 60, 169–180 (2019).

Ermer, A. E. & Proulx, C. M. Unforgiveness, depression, and health in later life: The protective factor of forgivingness. Aging Ment. Health. 20, 1021–1034 (2016).

Mullet, E., Houdbine, A., Laumonier, S. & Girard, M. ‘Forgivingness’: Factor structure in a sample of young, middle-aged, and elderly adults. Eur. Psychol. 3, 289–297 (1998).

Escher, D. How does religion promote forgiveness? Linking beliefs, orientations, and practices. J. Sci. Study Relig. 52, 100–119 (2013).

McCullough, M. E. & Worthington, E. L. Jr. Religion and the forgiving personality. J. Pers. 67, 1141–1164 (1999).

VanderWeele, T. J. et al. The Global Flourishing Study: Study profile and initial results on flourishing. Nat. Ment. Health (in press).

Crabtree, S., English, C., Johnson, B. R., Ritter, Z. & VanderWeele, T. J. Global Flourishing Study: Questionnaire Development Report. https://hfh.fas.harvard.edu/files/pik/files/globalflourishingstudy_report.pdf (2021)

Johnson, B. R. et al. The Global Flourishing Study. Open Sci. Framew. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3JTZ8 (2024).

Lomas, T. et al. The development of the Global Flourishing Study survey: Charting the evolution of a new 109-item inventory of human flourishing. BMC Glob. Public Health (in press).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Analytic methodology for demographic variation analyses for wave 1 of the Global Flourishing Study. BMC Glob. Public Health (in press).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Survey sampling design in wave 1 of the Global Flourishing Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. (in press).

Ritter, Z. et al. Global Flourishing Study methodology. Open Sci. Framew. https://osf.io/k2s7u (2024).

VanderWeele, T. J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 8148–8156 (2017).

Fetzer Institute. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research: A Report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute of Aging Working Group (1999).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2024).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods. 1, 97–111 (2010).

Hunter, J. E. & Schmidt, F. L. Fixed effects vs. random effects meta-analysis models: Implications for cumulative research knowledge. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 8, 275–292 (2000).

Mathur, M. B. & VanderWeele, T. J. Robust metrics and sensitivity analyses for meta-analyses of heterogeneous effects. Epidemiol. 31, 356–358 (2020).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Wilson, D. J. The harmonic mean p-value for combining dependent tests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 1195–1200 (2019).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Mathur, M. B. Some desirable properties of the Bonferroni correction: Is the Bonferroni correction really so bad? Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 617–618 (2019).

Sterne, J. A. C. et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338, b2393 (2009).

van Buuren, S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data (CRC, 2018).

Blanchflower, D. G. & Bryson, A. Seasonality and the female happiness paradox. Qual. Quant. 58, 1–33 (2024).

Cowden, R. G., Skinstad, D., Lomas, T., Johnson, B. R. & VanderWeele, T. J. Measuring wellbeing in the Global Flourishing Study: Insights from a cross-national analysis of cognitive interviews from 22 countries. Qual. Quant. 59, 575–597 (2025).

Haladyna, T. M. & Rodriguez, M. C. Developing and Validating Test Items (Routledge, 2013).

Berry, J. W., Worthington, E. L. Jr., O’Connor, L. E., Parrott, L. III & Wade, N. G. Forgivingness, vengeful rumination, and affective traits. J. Pers. 73, 183–226 (2005).

Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2, Article 8 (2011).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Global Flourishing Study statistical analyses code. Open Sci. Framew. https://osf.io/vbype/ (2024).

Funding

The Global Flourishing Study was supported by funding from the John Templeton Foundation (grant #61665), Templeton Religion Trust (#1308), Templeton World Charity Foundation (#0605), Well-Being for Planet Earth Foundation, Fetzer Institute (#4354), Well Being Trust, Paul L. Foster Family Foundation, and the David and Carol Myers Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.G.C. conducted the analyses and wrote the manuscript. K.S. and R.N.P. provided the code for data analysis. B.R.J. and T.J.V. acquired funding, coordinated data collection, participated in survey design, and supervised the development of the analytic code. E.L.W., C.C., J.H.D., D.W., G.Y., K.S., R.N.P., M.B., B.R.J., and T.J.V. contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Tyler J. VanderWeele reports consulting fees from Gloo Inc., along with shared revenue received by Harvard University in its license agreement with Gloo Inc. according to the University IP policy. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cowden, R.G., Worthington, E.L., Chung, C.A. et al. Sociodemographic variation in dispositional forgivingness: a cross-national analysis with 22 countries. Sci Rep 15, 12144 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82502-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82502-8