Abstract

Growth mindset, consistency of interest, and perseverance of effort have been demonstrated to positively influence students’ mathematical abilities. This study investigates how these characteristics interact and affect non-cognitive skills, enabling mathematics teachers to develop tailored interventions that enhance learning and persistence among rural students. We examined the profiles of growth mindset and Grit among 1495 rural Chinese students from three secondary schools in China, analyzing their relationships with math anxiety, motivation, and self-efficacy in mathematics lessons. Our analysis identified four distinct profiles: Fixed-Oriented Mindset, Lower Tendency Toward Growth, Tendency Toward Growth, and Growth-Oriented Mindset. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in students’ mathematics motivation between the Lower Tendency Toward Growth, Tendency Toward Growth, and Growth Mindset profiles. However, increases in mindset are associated with increased math anxiety among rural students. This research offers new insights into the effects of cultivating a growth mindset and Grit on mathematics anxiety among rural students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The landscape of mathematics education globally is marked by a pressing need to improve mathematical outcomes, a challenge that varies significantly across different educational environments1,2. In rural China, this need is particularly acute due to unique socio-economic and educational conditions that critically shape students’ learning experiences3. Rural schools in china often struggle with a scarcity of resources from limited access to advanced teaching materials to a shortage of qualified teaching staff4,5. These limitations are intensified by the high expectations placed on academic success, which is seen as a crucial pathway for social mobility within these communities.

In such rural environments, academic pressures not only increase but also create a complex psychological landscape among students6,7. This context makes the study of students’ mindsets whether they are ‘fixed’, believing abilities are unchangeable, or ‘growth’, seeing abilities as improvable through effort particularly relevant8. The presence of a Fixed-Oriented Mindset can lead to exacerbated feelings of academic inadequacy under intense pressure, hindering mathematical achievement9. Conversely, a growth mindset can encourage perseverance and effort, potentially improving mathematical outcomes over time10,11.

Moreover, the inclusion of grit, specifically its sub-factors of consistency of interest and perseverance of effort, is vital for understanding their role in educational persistence, especially critical in the rural schools of China12,13,14. Consistency of interest is particularly relevant in rural settings as it reflects how students maintain focus on their mathematical studies over time, despite environmental and emotional challenges15. Perseverance of effort describes the determination students exhibit in continuing their educational efforts amidst adversity16. Both factors are directly linked to three pivotal outcomes in education: math anxiety, motivation, and self-efficacy17,18,19.

Math anxiety is notably severe among students in rural China, often stemming from the continuous exposure to high-stress academic environments20, which can be mitigated or exacerbated by a student’s mindset and their level of grit. It is more pronounced in these students compared to their urban peers, often occupying working memory and inducing avoidance behaviors that limit practice and proficiency in mathematics21,22. Research by Ashcraft and Moore supports that adopting a growth mindset can mitigate these effects by normalizing challenges and failures as part of the learning process, thereby reducing anxiety and enhancing emotional engagement with mathematics23.

Motivation in rural settings is driven by both the intrinsic desire to succeed academically and the belief in one’s ability to improve despite educational challenges. For students in rural areas, this motivation is crucial as academic success is often seen as a key route to personal advancement24,25. Similarly, self-efficacy, or students’ belief in their capability to achieve specific outcomes, is significantly shaped by their mindset and the sustained effort they are prepared to invest26.

Furthermore, the importance of motivation and self-efficacy in this framework is underscored by Bandura’s social cognitive theory27, which suggests that self-efficacy may influence the choices people make, the effort they put forth, and their persistence in the face of challenges. In rural Chinese educational settings, where students often face significant academic and societal pressures, a growth mindset could potentially enhance both motivation and self-efficacy by promoting the belief that diligent effort can markedly improve one’s competence in mathematics. This belief might empower students to engage more actively with their studies and approach challenges with a solution-oriented mindset, possibly alleviating some of the educational pressures associated with high performance expectations.

Existing research has extensively profiled learners’ mindsets and grit, revealing significant influences on educational outcomes28,29. However, much of this research has not fully explored the non-linear interplay between mindset and grit factors, particularly in how they collectively influence math anxiety, motivation, and self-efficacy under varied socio-economic conditions. This gap is critical because understanding the combined effects of mindset and grit can offer deeper insights into students’ psychological and academic behaviors. This study seeks to fill these gaps by employing a person-centered approach to examine how these constructs manifest across different student profiles.

This study addresses this research gap by employing a person-centered approach, which allows for the examination of how distinct mindset profiles at the secondary school level correlate with non-cognitive skills such as grit, motivation, self-efficacy, and mathematics anxiety. The person-centered approach is valuable because it acknowledges the heterogeneity among students, revealing unique clusters of characteristics that can lead to different educational strategies and interventions tailored to specific student needs.

Our study aimed to address the following three key research questions:

-

1.

What are the profiles of mindset and Grit among secondary school students in rural China?

-

2.

How do the profiles of mindset and Grit relate to mathematics motivation, efficacy, and mathematics anxiety?

This approach not only deepens our understanding of how different mindsets impact students’ behaviors and skills but also offers insights into tailored educational strategies that could effectively support various student groups. By identifying distinct mindset profiles and their links to crucial non-cognitive outcomes such as grit, motivation, self-efficacy, and mathematics anxiety, educators can more accurately develop interventions aimed at boosting students’ academic and emotional well-being, particularly in challenging subjects like mathematics. Thus, this research provides a valuable framework for fostering environments that nurture resilience, persistence, and a positive approach to learning challenges, highlighting the importance of nuanced educational assessments and interventions. These insights and methodological choices underscore the potential of person-centered approaches in revealing diverse educational needs and crafting precise support mechanisms that cater to these variations.

Literature review

Role of mindset in educational contexts

The interplay between a growth mindset and Grit becomes particularly significant in the context of mathematics education among rural Chinese students. According to Carol Dweck’s theory of motivation30, students who perceive their intelligence as malleable may be more inclined to embrace challenging mathematical tasks. Dweck categorizes these beliefs into two primary mindsets: fixed and growth30. Students with a Fixed-Oriented Mindset perceive their intelligence as static a trait that cannot be altered through effort or education31,32. This view can lead to avoidance of challenging tasks, as these students may fear that struggling with difficult material exposes an inherent lack of ability9,33. In rural Chinese schools, where educational resources are often scarce and failure can carry heavy social stigmas, such mindsets can severely restrict students’ willingness to engage with complex subjects like mathematics.

Conversely, students with a growth mindset believe that their intelligence can be developed through dedication and hard work11,28,34. This perspective encourages the adoption of adaptive learning strategies, persistence in the face of challenges, and a willingness to embrace complexity. In the context of mathematics education, which demands incremental learning and sophisticated problem-solving, a growth mindset is particularly beneficial35,36. Students with this mindset are more likely to persist through difficulties, engage more deeply with mathematical concepts, and achieve higher levels of academic success34.

Moreover, while intelligence mindset focuses on academic capabilities, the moral mindset an aspect less discussed but equally significant pertains to beliefs about the malleability of one’s character and moral attributes37. In educational settings, a moral mindset can influence how students perceive ethical challenges and personal growth opportunities13. In rural areas, where educational and moral values are often tightly interwoven, fostering a moral mindset that encourages integrity, perseverance, and cooperation can complement the growth mindset, enriching students’ overall educational experience and promoting a more holistic approach to development.

Expanding on this theoretical framework provides a more robust foundation for understanding how mindsets specifically influence learning behaviors in rural students and offer clearer insights into the psychological states that are pivotal for academic engagement in challenging subjects like mathematics.

Additionally, research indicates that the cultivation of a growth mindset can be particularly transformative in environments characterized by resource constraints and high educational pressures12, such as those found in rural Chinese schools. Studies have shown that interventions aimed at fostering a growth mindset not only enhance students’ engagement with learning materials but also improve their overall academic performance38,39,40. In rural settings, where students might otherwise feel limited by their circumstances, a shift towards viewing intelligence as improvable can lead to increased motivation and effort. This psychological shift is critical as it encourages students to approach problems with a focus on growth and learning rather than a fear of failure. By promoting resilience and a positive perception of challenging tasks, educators may help mitigate some of the negative effects of anxiety and low self-efficacy often observed in these populations41,42. Moreover, fostering such a mindset could be crucial in reducing the achievement gap between rural and urban students, providing a more equitable educational landscape.

This study enriches the theoretical framework of mindsets by exploring both the intelligence and moral dimensions and their impact on learning behaviors among rural students. By focusing on how these mindsets correlate with key non-cognitive factors specifically math anxiety, motivation, and self-efficacy our analysis offers deeper insights into the psychological states that are critical for academic engagement and success. In rural Chinese educational settings, where students face unique challenges, understanding these associations is particularly crucial. A growth mindset can significantly alleviate math anxiety by encouraging a more resilient and positive approach to learning challenges. Simultaneously, it can enhance motivation and self-efficacy, empowering students to engage more fully with complex subjects like mathematics. Therefore, promoting such mindsets not only contributes to better academic outcomes but also supports the overall psychological well-being of students, thereby fostering a more supportive and effective educational environment in rural China. This study’s findings underscore the importance of integrating mindset-oriented strategies into educational practices to enhance student outcomes and provide a clearer path toward academic success in challenging environments.

Grit in psychological research

Grit has been widely recognized in psychological research as a critical predictor of success, surpassing traditional measures such as IQ and talent15,43. Central to the concept of grit are two key components: perseverance of effort and consistency of interest44. Perseverance of Effort refers to the intensity and sustained application of effort toward achieving a goal, regardless of immediate outcomes, difficulties, or plateaus in progress44. In the context of this study, a student who demonstrates high perseverance of effort would maintain consistent work intensity in mathematics, dedicating substantial time and energy to problem-solving even when facing difficult concepts or lacking immediate success. This element of grit encapsulates the endurance and tenacity dimension of the trait, highlighting an individual’s ability to push through setbacks and remain committed to their academic tasks.

Consistency of Interest, on the other hand, refers to the stability and durability of one’s focus on long-term goals and interests over time44. In the context of this study, it represents a student’s sustained commitment to mathematics as a subject of interest, resisting the temptation to shift focus toward other academic areas or extracurricular distractions. This aspect of grit reflects not short-term enthusiasm but a deep and enduring engagement with mathematics, characterized by long-term investment and minimal fluctuation in interests or goals.

These components were prominently featured in Angela Duckworth’s research, which linked higher levels of grit to significant achievements across various domains44. Duckworth’s studies44 suggest that grit is not merely about the intensity of effort but also about the duration and consistency with which individuals pursue their goals. Unlike momentary willpower or immediate motivational spikes, grit involves a long-term, sustained commitment that is fundamental in enabling individuals to maintain motivation and effort over periods lengthy enough to challenge and overcome substantial obstacles.

Empirical studies on grit employ various methodologies to measure this trait, often using the Grit Scale, which assesses the consistency of interests and perseverance of effort43,44. For this study, a combined approach was chosen, integrating Duckworth’s Grit Scale with complementary measures. Duckworth’s Grit Scale44 was selected due to its robust psychometric properties, extensive validation across diverse populations, we recognized the need to supplement this scale to capture the broader conceptualization of non-cognitive skills, particularly within the rural Chinese educational context.

To address this, we combined Duckworth’s Grit Scale with measures of growth mindset. The integration of mindset measures was crucial because, while grit encapsulates the persistence aspects of character, growth mindset as the belief in the malleability of one’s abilities through effort complements grit by providing a framework for understanding how students perceive challenges and setbacks. This combination is particularly relevant in rural Chinese settings where educational challenges are often magnified by resource constraints, and a mindset encouraging adaptability and persistence can significantly influence academic engagement and resilience. The inclusion of mindset measures alongside the Grit Scale allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the interplay between students’ persistence traits and their beliefs about learning.

Impact of mindset and grit on non-cognitive outcomes

Non-cognitive skills refer to a broad category of skills that are not directly related to cognitive intelligence but are crucial for academic success and personal development45,46. These include traits and abilities such as motivation47,48, efficacy49,50, and math anxiety51,52. In the context of educational research, these skills are increasingly recognized for their significant influence on students’ learning outcomes and overall educational trajectories. In this study, we focus on three specific non-cognitive skills: motivation, self-efficacy and mathematics anxiety. These skills were selected due to their critical roles in shaping students’ engagement and success in mathematics20,53,54, a subject that poses unique challenges due to its abstract nature and the high cognitive demands it places on learners.

According to the theoretical framework. the mindset a student holds, combined with their level of grit, can profoundly affect their non-cognitive skills55,56. A growth mindset, the belief that one’s abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work has been hypothesized to enhance motivation and efficacy while reducing anxiety57,58. When this belief is coupled with grit, the influence on non-cognitive outcomes becomes even more pronounced. Students who not only believe in the expandability of their intellectual abilities but also persist in their efforts regardless of setbacks are more likely to embrace challenges and persevere in the face of difficulties. This persistence is directly linked to increased motivation, as these students are driven to overcome obstacles, and to higher levels of self-efficacy, as they build confidence through their continued efforts and successes.

Furthermore, the combination of a growth mindset and grit can mitigate math anxiety. The endurance fostered by grit helps students face and manage the stress and frustration often associated with challenging mathematical concepts. This resilience, when paired with a growth mindset, allows students to view these challenges as opportunities for learning rather than threats to their intelligence, thereby reducing anxiety levels and enhancing overall academic engagement59,60. Such interventions could be particularly impactful in rural Chinese educational settings, where traditional educational pressures and resource limitations often exacerbate challenges related to motivation, efficacy, and anxiety61,62.

Methodology

Participants

This study focuses on secondary school students in rural areas, where it is known that these students often have less access to facilities, lower-quality teachers, and limited educational technology compared to their urban counterparts63,64. Additionally, rural areas possess distinct cultures that can influence the attitudes and behaviors of secondary students. By focusing on the growth mindset of secondary students in these regions, this research aims to provide new insights into enhancing non-cognitive skills in rural student populations.

The participants in this study were secondary school students from a rural region in China, representative of many underdeveloped areas across the country. These settings are typically characterized by limited educational resources, fewer facilitating conditions, minimal integration of educational technologies, and a lack of diverse or innovative teaching methods and models7,65. In China, Guangxi is one such region that reflects these characteristics. This setting, chosen for its underdeveloped status, allowed us to closely examine the educational challenges and behaviors of students, providing a clear backdrop to explore how such conditions impact their academic mindsets. We used a convenience sampling method for this study, engaging the support of two school principals in rural Guangxi to facilitate our research. Data collection was conducted over a period of three weeks. Four mathematics teachers entered each class and invited students to participate in the research. Participation was voluntary, with no pressure on students who chose not to fill out the questionnaire. Initially, raw data were collected from 1502 secondary school students ranging from grades 7 to 12. However, the final analysis included data from 1459 students who completed all required sections of our survey. included 677 male and 782 female students, comprising 1123 junior high school students and 336 senior high school students. All students were from public schools located in rural areas of Guangxi. The reduction in sample size was due to the exclusion of 43 students who did not answer all sections of the questionnaire, ensuring that only complete datasets were used for analysis.

It is important to note that before data collection, Additionally, the study’s procedures were rigorously reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Beijing Normal University. This approval was necessary to ensure that our research complied with all ethical guidelines and standards as outlined by the Helsinki Declaration, which governs the ethical principles for conducting research involving human subjects. This declaration emphasizes the need for voluntary participation, informed consent, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any penalty.

Measures

Mindset scale

For measuring the growth mindset, the data collection utilized the Implicit Theory Measures scale developed by Dweck and Yeager30. This scale comprises four items, divided equally between intelligence mindset and moral mindset, each with three statement items. An example item from the intelligence growth mindset is “Your intelligence is something about you that you can’t change very much,” and from the moral growth mindset, “Whether a person is responsible and sincere or not is deeply ingrained in their personality. It cannot be changed very much.” Originally, responses were collected on a scale from 1 (true) to 6 (not true); however, for consistency with other measures in this study, this was adjusted to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), with the scoring reversed accordingly. The growth mindset scale demonstrated high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, indicating strong internal consistency suitable for assessing the mindset traits of the study participants.

Grit

The data collection utilized the Short Grit Scale13,15,44, which was adapted and translated into Chinese to measure two facets of grit: Perseverance of Effort and Consistency of Interest. This scale features eight items, such as “I am diligent” to assess Perseverance of Effort and “I often set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one,” which is reverse-scored for Consistency of Interest. Responses were captured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability scores for the scales were satisfactory, with Consistency of Interest at a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72 and Perseverance of Effort at 0.79, confirming their appropriateness for gauging grit among Chinese secondary school students.

Student motivation

The development of our custom measures for motivation, self-efficacy, and anxiety was guided by the specific educational and cultural context of rural Chinese secondary school students. While there are established scales available, these often do not fully capture the unique challenges and environmental factors present in rural China. For instance, existing measures may not adequately reflect the linguistic nuances and cultural expressions of resilience and academic anxiety pertinent to our target population. Additionally, many standardized scales are developed with urban and Western contexts in mind, which can lead to cultural bias and misinterpretation when applied to rural Chinese settings.

To ensure the appropriateness and accuracy of our measures, we translated the items into Chinese, enhancing their relevance and comprehension for the local student population. Furthermore, to validate these custom measures, we engaged three experts in psychology, education, and mathematics who are knowledgeable about both the regional and subject-specific contexts. Their input was crucial in confirming the content validity of the items, ensuring that they accurately assess the intended constructs within the cultural and educational framework of rural Guangxi. This rigorous process of translation and expert validation supports the reliability and validity of our scales, making them suitable tools for assessing motivation, self-efficacy, and anxiety among rural Chinese students.

Drawing on prior studies53,66,67, we developed four items to assess how diligently participants engaged with their mathematics assignments. Responses were gathered using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The analysis confirmed that student motivation in the mathematics classroom formed a unidimensional construct, evidenced by robust fit indices (CFI = 0.980; SRMR = 0.026; RMSEA = 0.088). Moreover, the construct demonstrated high reliability and convergent validity, with a composite reliability index (ω) of 0.92, Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.90, and average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.65, indicating a well-defined and reliable measure.

Self-efficacy

We utilized four items to measure students’ self-efficacy regarding their mathematics abilities68,69,70. Responses were captured using the same 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Confirmatory factor analysis established that the self-efficacy construct was clearly defined and singular within the context of the mathematics classroom, as indicated by excellent fit indices (CFI = 0.975; SRMR = 0.022; RMSEA = 0.045). The construct also displayed high reliability and convergent validity, with a composite reliability index (ω) of 0.89, Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.87, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.62.

Mathematics anxiety

To further explore the emotional challenges associated with learning, we assessed mathematics anxiety with nine specifically designed items51,71,72, such as, “I feel nervous doing mathematics problems.” Additionally, anxiety experienced specifically during exams was measured using four distinct items, including, “I feel tense when I start an exam in mathematics.” Both sets of items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the mathematics anxiety construct was well-defined and robust, demonstrated by strong fit indices (CFI = 0.965; SRMR = 0.030; RMSEA = 0.055). The reliability and convergent validity of this construct were also confirmed with a composite reliability index (ω) of 0.91, Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.90, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.68. Similarly, the exam-specific anxiety construct showed excellent psychometric properties, with fit indices (CFI = 0.972; SRMR = 0.025; RMSEA = 0.049), a composite reliability index (ω) of 0.93, Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.92, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.70.

Data analysis

Research using a person-centered approach with latent profile analysis often employs MPlus software with robust maximum likelihood estimation to classify student profiles73. In this study, to identify profiles of secondary school students’ mindsets and grit, we utilized z-scores calculated with MPlus. These z-scores were standardized within our sample itself, allowing us to measure how each student’s score deviates from the sample mean in units of standard deviation. This method ensures that the analysis accounts for variance directly related to our specific sample, rather than relying on population norms which may not accurately reflect the unique characteristics of the rural school environment in which these students are situated. By standardizing within the sample, we are better equipped to identify and interpret the nuances of mindset and grit profiles specific to our study’s participants.

The number of latent profiles was determined by examining various fit indices along with the meaningfulness and parsimony of the extracted profiles. Fit indices were assessed by looking at the AIC, BIC, and SSA-BIC scores74,75, where lower scores indicate better model fit. We also employed the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Test (LMRT)76,77, where a significant p-value must not exceed 0.05. Additionally, the entropy value was used to determine the accuracy of the classification models75,78. Ideal profiles are those that include no less than 5% of the participants. Finally, to address Research Question 3, in person-centered studies, ANOVA is commonly used to explore the relationships among variables, determining whether they are significantly associated with the classification of profiles.

Findings

The purpose of this study is to explore the profiles of secondary school students’ mindsets and Grit in rural areas and to examine the relationships between these profiles and non-cognitive skills, specifically student motivation, self-efficacy, and mathematics anxiety in mathematics lessons.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and correlations among variables such as, Interest Consistency, Consistency of Effort, Motivation, Efficacy, and 79Anxiety. The correlations show strong positive relationships between Growth Mindset and both Interest Consistency and Consistency of Effort, suggesting that students with a Growth-Oriented Mindset are more likely to exhibit sustained interest and effort in their studies. Notably, the correlation between Efficacy and Anxiety is also very high, indicating that students with a Growth-Oriented Mindset may still experience high levels of mathematics anxiety.

Identification of Mindset and Grit Profiles Among Secondary School Students in Rural Areas

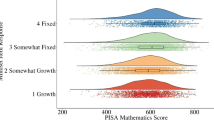

To address the first research question, we utilized Latent Profile Analysis. From the values of AIC, BIC, and SSA-BIC presented in Table 2, it is evident that these indices decrease as more profiles are added. Notably, the slope of the curve becomes flatter starting from the fourth profile (as shown in Fig. 1). Additionally, the fifth and sixth profiles were found to have samples comprising less than 5% of the total, which is significant77. Furthermore, the fifth profile shows a Lo-Mendell-Rubin Test (LMRT) p-value greater than 0.05, suggesting it is not statistically significant77. Previous research suggests that profiles representing less than 5% of the sample do not provide unique and meaningful information77. Based on these observations, we chose four profiles of student mindset in the rural area as the optimal solution.

Figure 2 illustrates the four profiles based on standardized z-scores for student mindset and grit. Each student’s mindset profile is defined by their z-score, which reflects each individual’s relative standing on these indicator variables compared to the sample mean. A z-score is a statistical measurement that describes a value’s relationship to the mean of a group of values, expressed in terms of standard deviations from the mean. Therefore, a low z-score with negative values indicates a Fixed-Oriented Mindset, suggesting that the student’s mindset is significantly below the average observed in the sample. Conversely, a high positive z-score indicates a Growth-Oriented Mindset, signifying that the student’s mindset is substantially above the average.

Based on standardized z-scores, four distinct profiles were identified and ordered from the lowest to the highest: Fixed-Oriented Mindset Profile, Lower Tendency Toward Growth Profile, Tendency Toward Growth Profile, and Growth-Oriented Mindset Profile. The Fixed-Oriented Mindset Profile, comprising 94 students (15% of the sample), includes individuals with the lowest, typically negative, z-scores. These students are characterized by a strong belief in fixed abilities and show limited confidence in effort as a means for improvement. The Lower Tendency Toward Growth Profile contains 627 students (41%) and represents a transitional group that has begun to recognize the importance of effort but has not fully internalized growth-oriented beliefs.

The Tendency Toward Growth Profile, including 250 students (16%), reflects students who more consistently accept and apply growth mindset principles, demonstrating increased resilience and engagement when facing academic challenges. Finally, the Growth-Oriented Mindset Profile, consisting of 488 students (32%), is defined by the highest positive z-scores. These students exhibit a strong belief that abilities can be developed through effort and perseverance, which supports higher levels of academic engagement and achievement.

The chart in Fig. 2 visualizes z-scores for three variables across four profiles, where z-scores represent the deviation of values from the mean in units of standard deviations. In the chart, the green bar represents Mindset, the blue bar represents Consistency of Interest, and the yellow bar represents Perseverance of Effort.

In conclusion, In rural areas of Guangxi, China the most prevalent student mindset is the Lower Tendency Toward Growth, as it encompasses the majority of the students at 41% of the sample. This indicates that while many students are on the path toward adopting a growth mindset, there is still significant work to be done to fully transition these students to a more Tendency Toward Growth or growth-oriented mindset. The high percentage in the Lower Tendency Toward Growth category suggests that interventions aimed at fostering a growth mindset could be particularly effective in this region.

Relationship between Latent profile and student motivations, self-efficacy and mathematics anxiety

To address the third research question, which focuses on the analysis of mindset profiles and Grit in relation to motivation, efficacy, and mathematics anxiety reveals distinct patterns that underscore the complexity of how these non-cognitive factors interact with students’ mindset. Notably, the motivation scores display a substantial increase when comparing students with a Fixed-Oriented Mindset to those with a Lower Tendency Toward Growth or Tendency Toward Growth. This pattern suggests that a shift towards a growth mindset is associated with enhanced motivation. However, the motivation scores among Lower Tendency Toward Growth, Tendency Toward Growth, and Growth-Oriented Mindset profiles do not differ significantly, suggesting that once a threshold of growth mindset is reached, motivation levels off. The F-statistic of 10.279, significant at a p-value less than 0.001, confirms that these differences across profiles are statistically significant, though the largest gap occurs at the transition from a fixed to a growth-oriented mindset. See Fig. 3 for details.

In terms of efficacy, there is a clear progressive increase across the mindset profiles, with students exhibiting the highest efficacy levels in the Tendency Toward Growth group. This trend is statistically robust, as evidenced by an F-statistic of 377.693, significant at p < 0.001, indicating a strong correlation between higher levels of growth mindset and increased self-efficacy. This suggests that as students more fully embrace the idea that their abilities can grow with effort, their efficacy in facing academic challenges significantly strengthens.

Interestingly, mathematics anxiety exhibits a distinctive pattern, with anxiety levels escalating from the Fixed-Oriented Mindset profile to the Growth-Oriented Mindset profile. The highest levels of anxiety are observed among students with a Growth-Oriented Mindset (Table 3). This may reflect the pressures and challenges associated with higher engagement and elevated personal and academic expectations. The F-statistic of 412.257, significant at p < 0.001, confirms that this increase in anxiety across profiles is statistically significant. This suggests a complex interaction whereby higher levels of a growth mindset may lead to increased anxiety, possibly due to the greater stakes involved in more intense academic engagement.

Discussion

In this study, we identified four distinct profiles of mindset and grit among secondary school students in rural areas. The Fixed-Oriented Mindset Profile includes 94 students (15% of the sample) who believe their abilities are static and unchangeable. This belief often leads to lower academic engagement and a tendency to avoid challenging tasks. The Lower Tendency Toward Growth Profile, the largest group with 627 students (41%), represents students who occasionally demonstrate effort and engagement but lack consistency. Educational strategies for this group should focus on reinforcing growth mindset beliefs through positive feedback and illustrating the tangible benefits of sustained effort and resilience.

The Tendency Toward Growth Profile consists of 250 students (16%) who generally endorse growth mindset principles and show increased engagement. However, there remains potential for these beliefs to be more fully integrated into all areas of their academic experience. For this group, opportunities such as advanced problem-solving tasks and peer teaching may help deepen their commitment to growth-oriented behaviors. Lastly, the Growth-Oriented Mindset Profile includes 488 students (32%) who strongly believe that abilities can be developed through effort and persistence. Despite being the most adaptive profile, this group still constitutes only a minority of the rural student population. These findings highlight the importance of designing targeted educational strategies tailored to each profile to help students progress from a fixed to a growth mindset. Supporting this approach, previous research has shown that well-designed interventions can significantly enhance both mindset and grit, leading to improved academic and personal outcomes8,79,80.

The study indicates that a shift from a Fixed-Oriented Mindset to a Lower Tendency Toward Growth Mindset is associated with higher levels of student motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation, where students are driven by personal growth and learning81,82. This association suggests that the initial development of growth-oriented beliefs correlates with increased motivational engagement. However, motivation does not show a significant upward trend as students move from the Tendency Toward Growth to the Growth-Oriented Mindset profiles. This pattern implies that while early mindset development is related to improvements in motivation, further refinement of mindset beliefs does not necessarily correspond with additional motivational gains. Additionally, while adopting a growth mindset generally benefits efficacy83,84, it flexibly influences student mathematics motivation9.

Lastly, our study observed a correlation where increases in students’ mindset and grit were associated with higher levels of mathematics anxiety. This finding contrasts with previous research, which has typically found that grit is negatively associated with anxiety levels85. This correlation might be explained by the possibility that students with a Growth-Oriented Mindset and heightened self-efficacy tend to set higher personal standards and goals86,87. As they strive to meet these elevated expectations, they might experience increased anxiety levels. Considering that the sample in this study comprises rural students, this phenomenon can be further understood within the context of rural Chinese communities. These communities often harbor a strong desire for a better life, believing that education can change their future88,89. This drives children to aspire to attend top schools in cities, which in turn enhances their growth mindset and consequently increases their mathematics anxiety. This phenomenon warrants careful attention from parents, teachers, and community members to support students in managing their anxiety while fostering a constructive educational environment.

Theoretical implications

This study challenges the widely held assumption that a growth mindset consistently reduces academic anxiety. Among rural Chinese students, a stronger growth mindset was associated with increased mathematics anxiety a finding that runs counter to established theory. This suggests that the psychological impact of growth mindset is not universal but shaped by contextual factors such as socioeconomic pressure and limited access to academic and emotional support.

In rural settings, academic success is often viewed as the primary path to upward mobility, placing intense pressure on students to succeed. When effort does not lead to expected outcomes, students may experience maladaptive anxiety, characterized by performance catastrophization and somatic symptoms. Rather than interpreting failure as a learning opportunity, they may internalize it as a personal deficiency (“I worked hard but still failed. there must be something wrong with me”).

This finding expands existing theoretical frameworks by highlighting the potential for growth mindset to produce unintended emotional burdens in high-pressure, resource-constrained environments. It underscores the importance of integrating sociocultural and structural considerations into mindset research, and calls for a more nuanced understanding of how motivational beliefs interact with students’ lived realities.

Additionally, These findings collectively suggest that the development of a growth mindset and grit in educational settings is influenced by a variety of factors, including cultural context and and that these factors may interact in complex ways with students’ learning experiences and emotional responses to education.

Practical implications

This study underscores several practical implications for educational stakeholders, particularly highlighting the need for supportive environments that foster a growth mindset among students in rural settings. Our research indicates that children with a Growth-Oriented Mindset might experience heightened levels of stress, likely due to the pressures they place on themselves to continuously improve and meet high expectations. Thus, educators and parents should prioritize creating nurturing environments that emphasize resilience and effort over perfection. This involves valuing the learning process itself and acknowledging the effort students put into overcoming challenges, rather than focusing solely on the outcomes of their endeavors.

To effectively promote a growth mindset, teachers can integrate classroom activities that encourage problem-solving and critical thinking, helping students engage directly with challenges90,91. Group projects that require collaborative learning can serve as excellent platforms for this92, as they highlight shared efforts and collective improvement, reinforcing the notion that abilities can develop through teamwork and persistent effort. Furthermore, it is crucial for teachers to praise students for their strategic approaches and perseverance, rather than just the correctness of their answers93. Such recognition helps students appreciate the value of their learning journey and understand that errors are part of personal and academic growth.

Additionally, educators should explicitly teach strategies for navigating academic and emotional challenges. Workshops or lessons focused on time management, emotional regulation, and effective study techniques can equip students with necessary skills to manage the academic pressures typical of rural educational settings. Regular reflective sessions or assessments where students discuss their learning experiences and the challenges, they’ve faced can also be beneficial. These discussions can be facilitated through tools like learning journals or portfolios, allowing students to document their progress and reflect on their experiences. This practice not only helps educators monitor shifts in students’ attitudes towards learning but also enables them to provide tailored feedback that supports individual growth.

Educators aiming to foster a growth mindset must also remain attentive to the possibility of increased anxiety, particularly among students who may feel overwhelmed by the expectation to constantly persist and improve. To strike a balance, teachers should normalize struggle as a natural part of the learning process without overemphasizing the need for continuous effort. Encouraging students to set realistic, manageable goals can help build confidence without creating unnecessary pressure. Providing process-focused feedback highlighting strategies, progress, and learning approaches rather than just praising effort can reinforce growth-oriented beliefs in a supportive manner. Additionally, creating a low-stakes classroom environment, where mistakes are treated as learning opportunities and students are given the chance to revise their work, can reduce fear of failure. It is also important for educators to remain sensitive to signs of stress or withdrawal and offer emotional support when needed. Teaching students simple self-regulation strategies, such as mindfulness or reflective journaling, can further help them manage academic pressure while maintaining their belief in personal growth.

Professional development for teachers on the principles of a growth mindset is essential. Ensuring that teachers are well-equipped with the knowledge and skills to foster and support mindset development among students is paramount. Such training should include identifying behaviors indicative of a Fixed-Oriented Mindset and offering strategies to encourage a more growth-oriented approach among students. However, this study also highlights that growth mindset interventions must be contextually adapted. In rural Chinese settings, where academic pressure is amplified by limited resources and strong familial expectations, effort may be perceived as a moral duty rather than a path to personal growth. Failure, in this context, can lead to maladaptive anxiety rather than resilience.

Unlike Western or urban environments where students benefit from abundant academic and emotional support, rural students often lack such buffers. Cultural beliefs may also shape how effort and ability are interpreted, with academic success closely tied to family honor and future security. Therefore, growth mindset programs in rural schools should be accompanied by stress management strategies, socio-emotional learning supports, and teacher training that addresses the psychological and cultural realities faced by students. Without these supports, well-intentioned interventions may unintentionally increase anxiety and self-doubt.

Limitations and conclusion

It is important to recognize that no research is without limitations, and this study has several that could inform future investigations. First, we employed a convenience sampling method involving six secondary schools in rural areas of Guangxi. Therefore, It is important to note that these results may not fully generalize to other rural contexts or educational systems with different cultural values and expectations. In rural communities where academic competition is less intense or where alternative pathways to success are more culturally accepted, the relationship between growth mindset, grit, and anxiety may differ. Future research should explore these dynamics across diverse rural and international settings to better understand how cultural and systemic factors mediate the link between psychological traits and academic anxiety. Further research across diverse rural regions and educational systems is necessary to assess the broader applicability of our conclusions.

Second, considering that our latent profile analysis (LPA) relied on self-reported data via questionnaires, there is a potential for social desirability bias to influence the results94. Third, while this study examined how different profiles of mindset and grit influence Math Anxiety, Motivation, and Self-Efficacy, we acknowledge that these profiles could also impact other mathematical abilities of students. Future research might explore these additional dimensions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence student performance.

In conclusion, Student growth mindset and grit are crucial for enhancing both cognitive and non-cognitive skills in secondary school students. Our research identified four distinct profiles of mindset and grit among secondary students in rural areas, an approach that aptly addresses the complexities of mindset and grit at this educational level. Further analysis of these profiles revealed that improvements in students’ mindset and grit are accompanied by an increase in mathematics anxiety. However, a positive aspect is that such improvements are also linked with enhanced self-efficacy in mathematics learning. This study provides valuable insights for educators on the dynamics between student mindset, grit, and non-cognitive development. While it is beneficial to foster growth mindset and grit, it is also crucial to monitor the accompanying rise in mathematics anxiety to ensure the maximal development of students’ non-cognitive skills. This understanding should guide interventions aimed at boosting student efficacy and performance in challenging academic subjects.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this research will be made available upon request by the author of this publication. Interested researchers should contact the corresponding author of this publication, Tommy Tanu Wijaya, at [email protected].

References

Ito, T., Ishii, K., Nishi, M., Shin, M. & Miyazaki, K. Comparison of the effects of the integrated learning environments between the social science and the mathematics. In SEFI 47th Annual Conference: Varietas Delectat... Complexity is the New Normality, Proceedings, 550–558 (2020). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85077824105&partnerID=40&md5=bd9da6a797f3cb8f7b6abe13bc047a85

Dignath, C. & Büttner, G. Teachers ’ direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes—Insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacognit. Learn. 13(2), 127–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-018-9181-x (2018).

Aunio, P. et al. Young children’s number sense in China and Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 50(5), 483–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600953576 (2006).

Wang, P.-Y. Examining the digital divide between rural and urban schools: Technology availability, teachers’ integration level and students’ perception. J. Curric. Teach. 2(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v2n2p127 (2013).

OECD. Education in China: A Snapshot. https://www.oecd.org/china/Education-in-China-a-snapshot.pdf (2016). https://www.oecd.org/china/Education-in-China-a-snapshot.pdf

Liu, G. X. Y. & Helwig, C. C. Autonomy, social inequality, and support in Chinese Urban and Rural Adolescents’ Reasoning About the Chinese College Entrance Examination (Gaokao). J. Adolesc. Res. 37(5), 639–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558420914082 (2022).

Wu, D., Zhou, C., Liang, X., Li, Y. & Chen, M. Integrating technology into teaching: Factors influencing rural teachers’ innovative behavior. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27(4), 5325–5348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10815-6 (2022).

Burnette, J. L., Russell, M. V., Hoyt, C. L., Orvidas, K. & Widman, L. An online growth mindset intervention in a sample of rural adolescent girls. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 88(3), 428–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12192 (2018).

Limeri, L. B. et al. Growing a growth mindset: characterizing how and why undergraduate students’ mindsets change. Int. J. STEM Educ. 7(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00227-2 (2020).

de Ruiter, N. M. P., van der Klooster, K. N. & Thomaes, S. ‘Doing’ mindsets in the classroom: A coding scheme for teacher and student mindset-related verbalizations. J. Pers. Res. 6(2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.17505/JPOR.2020.22404 (2020).

Mason, S., Weeden, E. & Bogaard, D. Building a growth mindset toolkit as a means toward developing a growth mindset for faculty interactions with students in and out of the classroom: Building a growth mindset toolkit for faculty. In SIGITE 2022—Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference on Information Technology Education, 137–141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1145/3537674.3554750.

Wolcott, M. et al. A review to characterize and map the growth mindset theory in health professions education. Med. Educ. 55, 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14381 (2020).

Herdian, H., Qingrong, C. & Nuryana, Z. Unlocking the power of growth mindset: strategies for enhancing mental health and well-being among college students during COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 43(19), 17956–17966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05342-1 (2024).

Kim, E. & Park, Y. Relations of College Students’ Values to their Academic Attitudes and Achievement. Korean J. Educ. Res. 59(1), 227–258 (2021).

Al-Zain, A. O. & Abdulsalam, S. Impact of grit, resilience, and stress levels on burnout and well-being of dental students. J. Dent. Educ. 86(4), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12819 (2022).

Karlen, Y., Suter, F., Hirt, C. & Merki, K. M. The role of implicit theories in students’ grit, achievement goals, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and achievement in the context of a long-term challenging task. Learn. Individ. Differ. 74, 101757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101757 (2019).

Guo, W., Bai, B., Zang, F., Wang, T. & Song, H. Influences of motivation and grit on students’ self-regulated learning and English learning achievement: A comparison between male and female students. System 114, 103018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103018 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. The impact of a growth mindset on high school students’ learning subjective well-being: The serial mediation role of achievement motivation and grit. Front. Psychol. 15, 1399343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1399343 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. From growth mindset to grit in Chinese schools: The mediating roles of learning motivations. Front. Psychol. 9, 2007. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02007 (2018).

Tezer, M. & Karasel, N. Attitudes of primary school 2nd and 3rd grade students towards mathematics course. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2(2), 5808–5812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.947 (2010).

Xie, Y., Lan, X. & Tang, L. Gender differences in mathematics anxiety: A meta-analysis of Chinese children. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 248, 104373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104373 (2024).

Liu, H., Shi, Y., Auden, E. & Rozelle, S. Anxiety in rural chinese children and adolescents: Comparisons across provinces and among subgroups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15(10), 2087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102087 (2018).

Ashcraft, A. M. & Moore, M. H. Mathematics anxiety and the affective drop in performance. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 27(3), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282908330580 (2009).

Kyung, P. S. & Hoon, B. S. The effect of university students’ growth mindset on meta-cognitive strategies: The mediating effect of grit. J. Wellness 16(1), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.21097/ksw.2021.02.16.1.102 (2021).

Lam, K. K. L. & Zhou, M. A Meta-analysis of the relationship between growth mindset and grit. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 255, 104872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.104872 (2025).

Byun, K. & Gyu-Pan, C. H. O. The mediating effect of meta-cognition, grit on the relationship between growth mindset and self-directed learning ability of middle school students. J. Educ. Dev. 44(1), 95–121 (2024).

Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory (Prentice-Hall, 1986).

Sigmundsson, H., Guðnason, S. & Jóhannsdóttir, S. Passion, grit and mindset: Exploring gender differences. New Ideas Psychol. 63(April), 100878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100878 (2021).

Sigmundsson, H., Haga, M. & Hermundsdottir, F. Passion, grit and mindset in young adults: Exploring the relationship and gender differences. New Ideas Psychol. 59(12), 100795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2020.100795 (2020).

Dweck, D. S. & Yeager, C. S. Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14(3), 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166 (2019).

Sato, M. Mindsets and language-related problem-solving behaviors during interaction in the classroom. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 16(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2021.1895803 (2022).

Heyder, A., Weidinger, A. F. & Steinmayr, R. Only a burden for females in math? Gender and ___domain differences in the relation between adolescents’ fixed mindsets and motivation. J. Youth Adolesc. 50(1), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01345-4 (2021).

Jin, K. D. & 이영주. The mindset and peer relationships of elementary school students: The mediating effect of grit and self-regulation. Korean Soc. Study Phys. Educ. 24(2), 209–222 (2019).

Sousa, B. J. & Clark, A. M. Growth mindsets in academics and academia: A review of influence and interventions. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2024.2384003 (2025).

Hye, Y. S. & Kim, M.-H. Academic self-efficacy, academic failure tolerance, and grit in male high school students: The mediating effect of achievement goal orientation. Korean J. Youth Stud. 31(4), 27–56 (2024).

Jacquez, F., Trott, C. D., Wren, A. R., Ashraf, L. J. & Williams, S. E. Dream it! Preliminary evidence for an educational tool to increase children’s optimistic thinking. Child Youth Care Forum 49(6), 877–892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09561-6 (2020).

Bin, P. H. Strategy for using grit and growth mindset based on questioning in moral education. J. Ethics 1(126), 117–149. https://doi.org/10.15801/je.1.126.201909.117 (2019).

Zhao, H., Xiong, J., Zhang, Z. & Qi, C. Growth mindset and college students’ learning engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: A serial mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12(February), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621094 (2021).

Xiao, F. et al. The relationship between a growth mindset and the learning engagement of nursing students: A structural equation modeling approach. Nurse Educ. Pract. 73, 103796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103796 (2023).

Vestad, L. & Bru, E. Teachers’ support for growth mindset and its links with students’ growth mindset, academic engagement, and achievements in lower secondary school. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 27(4), 1431–1454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09859-y (2024).

Yamamoto, T., Nishinaka, H. & Matsumoto, Y. Relationship between resilience, anxiety, and social support resources among Japanese elementary school students. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 7(1), 100458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100458 (2023).

Shen, Y. Mitigating students’ anxiety: The role of resilience and mindfulness among Chinese EFL learners. Front. Psychol. 13(July), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.940443 (2022).

Han, C. W. Structural relations among achievement goals, perceptions of classroom goals, and grit. Curr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02891-9 (2022).

Guo, M. The relationship between students’ grit and mathematics performance: The mediational role of deep and surface learning strategies. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 33(2), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00735-z (2024).

Konstantopoulos, S. & Shen, T. Class size and teacher effects on non-cognitive outcomes in grades K-3: a fixed effects analysis of ECLS-K:2011 data. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 11(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-023-00182-8 (2023).

Vanbecelaere, S. et al. The effects of two digital educational games on cognitive and non-cognitive math and reading outcomes. Comput. Educ. 143, 103680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103680 (2020).

Es-Sajjade, A. & Paas, F. Educational theories and computer game design: Lessons from an experiment in elementary mathematics education. ETR&D-Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68(5), 2685–2703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09799-w (2020).

Bhagat, K. K., Yang, F. Y., Cheng, C. H., Zhang, Y. & Liou, W. K. Tracking the process and motivation of math learning with augmented reality. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 69(6), 3153–3178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10066-9 (2021).

Graham, M. C. C. et al. The relations between students’ belongingness, self-efficacy, and response to active learning in science, math, and engineering classes. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 45(15), 1241–1261. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2023.2196643 (2023).

Li, L., Peng, Z., Lu, L., Liao, H. & Li, H. Peer relationships, self-efficacy, academic motivation, and mathematics achievement in Zhuang adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, 105358 (2020).

Xiao, F. & Sun, L. Students’ motivation and affection profiles and their relation to mathematics achievement, persistence, and behaviors. Front. Psychol. 11(January), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.533593 (2021).

O’Brien, S., VanderSandt, S., & Johnson, E. D. Math anxiety and math teaching beliefs of a K-5 integrated-STEM major compared to other teacher preparation majors (2011). [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85029069936&partnerID=40&md5=3a441f6e0f1a56235c7d88e51df7fcee

Fiorella, L. et al. Validation of the Mathematics Motivation Questionnaire (MMQ) for secondary school students. Int. J. STEM Educ. 8(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-021-00307-x (2021).

Larkin, K. & Jorgensen, R. ‘I hate maths: Why do we need to do maths?’ Using iPad video diaries to investigate attitudes and emotions towards mathematics in year 3 and year 6 students. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 14(5), 925–944. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9621-x (2016).

Zander, L., Brouwer, J., Jansen, E., Crayen, C. & Hannover, B. Academic self-efficacy, growth mindsets, and university students’ integration in academic and social support networks. Learn. Individ. Differ. 62, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.01.012 (2018).

Kim, H. Exploring the interplay of language mindsets, self-efficacy, engagement, and perceived proficiency in L2 learning. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11(1), 1295. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03783-y (2024).

Hatcher, L. Z. Case Study: Changes in Elementary Student Mindset after Mathematics Anxiety and Growth Mindset Teacher Training (Concordia University (Oregon), Education, Oregon, 2018).

Hopkins, S. R., Rae, V. I., Smith, S. E. & Tallentire, V. R. Trainee growth vs. fixed mindset in clinical learning environments: enhancing, hindering and goldilocks factors. BMC Med. Educ. 24(1), 1199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06211-6 (2024).

Bi, Q. C. & Collins, J. Proactivity, mindsets and the development of students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy: behavioural skills as the catalyst. J. R. Soc. New Zeal. 52(5), 526–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2021.1999993 (2022).

Trice, J., Challoo, L., Hall, K. & Huskin, P. Relationship between mindset and self-efficacy among special education teachers. Res. High. Educ. J. 44(1), 11 (2023).

Li, Y., Tian, Y., Zhao, W., Oubibi, M. & Ding, Y. Teaching in China’s Heartland: A qualitative exploration of rural teacher job satisfaction. Heliyon 10(18), e38092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38092 (2024).

Yiu, L. & Yun, L. China’s rural education: Chinese migrant children and left-behind children. Chin. Educ. Soc. 50(4), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611932.2017.1382128 (2017).

Zheng, L., Qi, X. & Zhang, C. Can improvements in teacher quality reduce the cognitive gap between urban and rural students in China?. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 100, 102781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102781 (2023).

Mustafa, F., Nguyen, H. T. M. & (Andy) Gao, X. The challenges and solutions of technology integration in rural schools: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 126, 102380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102380 (2024).

Zhou, Y., Li, X. & Wijaya, T. T. Determinants of behavioral intention and use of interactive whiteboard by K-12 teachers in remote and rural areas. Front. Psychol. 13(June), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.934423 (2022).

Yuan, Z., Liu, J., Deng, X., Ding, T. & Wijaya, T. T. Facilitating conditions as the biggest factor influencing elementary school teachers’ usage behavior of dynamic mathematics software in China. Mathematics 11(6), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11061536 (2023).

Qin, L. et al. Reduction of academic burnout in preservice teachers: PLS-SEM approach. Sustainability 14, 13416 (2022).

Zhao, W. X., Peng, M. Y. P. & Liu, F. Cross-cultural differences in adopting social cognitive career theory at student employability in PLS-SEM: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and deep approach to learning. Front. Psychol. 12(June), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.586839 (2021).

Gan, C. L. & Balakrishnan, V. Mobile technology in the classroom: What drives student-lecturer interactions?. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 34(7), 666–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2017.1380970 (2018).

Wang, X., Wallace, M. P. & Wang, Q. Rewarded and unrewarded competition in a CSCL environment: A coopetition design with a social cognitive perspective using PLS-SEM analyses. Comput. Human Behav. 72, 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.045 (2017).

Marbán, J. M., Palacios, A. & Maroto, A. Enjoyment of teaching mathematics among pre-service teachers. Math. Educ. Res. J. 33(3), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-020-00341-y (2021).

Albelbisi, N. A., Al-Adwan, A. S., Habibi, A. & Rasool, S. The relationship between students’ attitudes toward online homework and mathematics anxiety. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2021.2023769.

Wijaya, T. T., Yu, Q., Cao, Y., He, Y. & Leung, F. K. S. Behavioral sciences latent profile analysis of AI literacy and trust in mathematics teachers and their relations with AI dependency and 21st-century skills. Behav. Sci. (Basel, Switzerland) 14 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Linking teacher support to achievement emotion profile: the mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 15(August), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1352337 (2024).

Yang, K., Gan, Z. & Sun, M. EFL students’ profiles of English reading self-efficacy: Relations with reading enjoyment, engagement, and performance. Lang. Teach. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241268891 (2024).

Xu, J. Student-perceived teacher and parent homework involvement: Exploring latent profiles and links to homework behavior and achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 109(August 2023), 102403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102403 (2024).

Sun, Q. et al. Stress, coping and professional identity among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a latent profile analysis. Curr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06554-9 (2024).

Hwang, S. Profiles of mathematics teachers ’ job satisfaction and stress and their association with dialogic instruction. Sustainability 14(11), 6925 (2022).

Shaari, Z. H., Amar, A., Harun, A. & Zainol, M. Exploring the mindsets and well-being of rural secondary school students in Perak, Malaysia. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. An Int. J. 9, 728–737 (2017).

Sihombing, L. Changing Society’s Mind Set in Managing Rural Development: A Way of Educators in Balancing Prosperity of Cities and Rural Areas (2020). https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200311.001

Suman, C. Implications of intrinsic motivation and mindset on learning. Zenodo 1, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8154574 (2023).

Ng, B. The neuroscience of growth mindset and intrinsic motivation. Brain Sci. 8(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8020020 (2018).

Westphal, A., Schulze, A., Schlesier, J. & Lohse-Bossenz, H. Who thinks about dropping out and why? Cognitive and affective-motivational profiles of student teachers explain differences in their intention to quit their teaching degree. Teach. Teach. Educ. 150(November 2023), 104718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104718 (2024).

Won, S. & Wolters, C. A. Understanding the relations between achievement goals and self-regulated learning: A multiple goal perspective. Educ. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2024.2392013 (2024).

Pollack, C. et al. Anxiety, motivation, and competence in mathematics and reading for children with and without learning difficulties. Front. Psychol. 12(October), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704821 (2021).

Piedmont, R. L. The relationship between achievement motivation, anxiety, and situational characteristics on performance on a cognitive task. J. Res. Pers. 22(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(88)90013-X (1988).

Welesilassie, M. W. & Nikolov, M. Relationships between motivation and anxiety in adult EFL learners at an Ethiopian university. Ampersand 9, 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2022.100089 (2022).

Lu, L., Kao, S.-F., Siu, O. & Lu, C.-Q. Work stress, chinese work values, and work well-being in the greater China. J. Soc. Psychol. 151, 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2010.538760 (2011).

Boon, H. T. Hardening the hard, softening the soft: assertiveness and China’s regional strategy. J. Strateg. Stud. 40(5), 639–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1221820 (2017).

Danday, B. A. & Monterola, S. L. C. Effects of microteaching physics lesson study on pre-service Teachers’ critical thinking. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 18(5), 692–707. https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/19.18.692707 (2019).

Mursalin, M. The critical thinking abilities in learning using elementary algebra e-books: A case study at public universities in Indonesia. Malikussaleh J. Math. Learn. 2(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.29103/mjml.v2i1.2292 (2019).

Li, R., Kan, G. & Cao, Y. Teacher noticing in the process of students’ collaborative problem solving—Based on an eye-tracking study of 15 pre-service mathematics teachers. J. Math. Educ. 30(02), 42–47 (2021).

Wijaya, T. T. et al. The impact of digital mathematics textbooks on teacher-student interaction: Evidence from behavioral sequence analysis the impact of digital mathematics textbooks on teacher-student interaction : evidence from behavioral sequence analysis. Int. J. Human-Comput. Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2024.2426033 (2024).

Zhao, S., Dong, Y. & Luo, J. Profiles of teacher professional identity among student teachers and its association with mental health. Front. Public Health 10(April), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.735811 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Informed consent: Parental informed consent forms were distributed and collected. Ethics Declarations: Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of School of mathematical sciences, Beijing Normal University on March 8, 2024, ensuring that all research involving human participants was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to data collection, both the principals and mathematics teachers at the participating schools endorsed the study, facilitating the distribution and collection of questionnaires by school administrators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T.W. conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, and led the writing of the original draft. X.L. performed the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y.C. assisted in data collection and preparation, and contributed to the revision and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wijaya, T.T., Li, X. & Cao, Y. Profiles of growth mindset and grit among rural Chinese students and their associations with math anxiety, motivation, and self-efficacy. Sci Rep 15, 21513 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07400-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07400-z