Abstract

Transabdominal preperitoneal patch plasty (TAPP) versus total extraperitoneal patch plasty (TEP) are surgical techniques commonly used to treat inguinal hernia. However, studies indicate that both procedures may lead to significant complications, particularly gastrointestinal complications, some of which can be life-threatening. We statistically analyzed the complications caused by adult inguinal hernia patients admitted from 2018 to 2022. We focused on gastrointestinal complications and conducted a case-by-case analysis on their causes and treatment processes. A total of 1034 patients were included in the final analysis, with 783 patients receiving TAPP treatment and 251 patients undergoing TEP. The overall complication rate for the TAPP group was slightly higher at 4.72% compared to 3.58% in the TEP group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.446). The incidence of both common and gastrointestinal complications is similar between the two groups, with no significant difference observed. Five patients (0.48%) suffered gastrointestinal complications, one with gastric perforation after TEP surgery, and four during TAPP surgery. All five cases of gastrointestinal complications were Grade III or higher according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, and all required reoperation. Gastrointestinal complications, though rare in LIHR, often require readmission and reoperation. Attempting non-operative management of such complications may lead to disastrous consequences. The majority of these complications are attributed to improper use of surgical instruments, necessitating vigilance on the part of the surgical team in preventing them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inguinal hernias are a common surgical condition, affecting around 220 million people worldwide1. Surgery is the only effective treatment for this condition, with approximately 20 million people requiring surgical intervention for inguinal hernias every year2. Open or minimally invasive techniques can be used for repairing inguinal hernias. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR) has been performed for over 30 years since transabdominal preperitoneal patch plasty (TAPP) was first reported by Arregui in 1991 and total extraperitoneal patch plasty (TEP) was first reported by McKernan in 19933,4. LIHR operation shows the advantages of quick recovery, low recurrence rate, small incision, and slight postoperative pain. The overall cost is similar to, or even lower than, that of open repair through effective cost control. Therefore, no matter from the perspective of either hospital or society, LIHR operation has good health-economic advantages.

The increase in surgical procedures for LIHR has led to a corresponding increase in the number of complications following surgery. Previous reports have primarily focused on relatively common complications such as postoperative pain, recurrence, seroma, hematoma, and patch infection. However, less attention has been paid to relatively rare complications such as bowel obstruction and bowel fistula after the operation. Although these complications are rare, they may still occur during surgical procedures owing to the high number of inguinal hernia operations performed each year. Therefore, it is crucial for healthcare practitioners to remain alert and implement appropriate strategies to prevent and address these potential complications.

Rare complications following LIHR were prospective study. The literature on each complication was reviewed.

Patients and methods

Data and patients

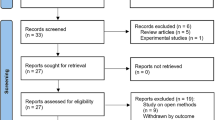

The clinical data of adult inguinal hernia patients admitted to the Department of Hernia and Abdominal Surgery at our hospital from January 2018 to December 2022 was prospectively studied. All procedures performed in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanxi Bethune Hospital and conducted strictly in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration (revised in 2013). Participants were informed about the purpose, process, risks, and benefits of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study. Data collected from patients undergoing primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair via either TAPP or TEP were analyzed. Recurrent hernia, incarcerated or strangulated hernia, patients with previous severe abdominal surgery, and pregnant women were excluded. A total of 1063 patients met the inclusion criteria. Follow-up was carried out at 1 week, 2 weeks, and 6 weeks after the operation, and then every 6 months. The follow-up time ranged from 6 to 42 months. Twenty-nine patients were lost to follow-up, and the remaining 1034 patients were statistically analyzed. The patients included in the statistics had a course of 1–20 years, and the median was 3 years. The mean age was 51.6 years, and the average BMI was 24.18. Among the 1034 patients, 929 were male and 105 were female. There were 795 cases of right hernia and 239 cases of left hernia. There were 121 cases of sliding hernia.

Surgical method

All operations were performed under general anesthesia. All operations were performed by doctors who completed the learning curve of laparoscopic hernia repair in more than 100 cases. Among 1034 patients, 783 patients underwent TAPP, and 251 patients underwent TEP.

Diabetic patients used antibiotics once before the operation, and the rest of the patients did not use antibiotics routinely before the operation. There were no routine indwelling gastric tube and urinary tube before the operation. 4 patients had an indwelling gastric tube after the operation, among which 3 patients had intestinal obstruction, and 1 patient found a perforation of the digestive tract after the operation. 10 patients had difficulty urinating after the operation, so they were indwelled with catheters and had them removed the next morning.

Statistical analysis

Clavien-Dindo classification was used to study intraoperative and postoperative complications. All the analyses were carried out by SPSS 22 software. Fisher’s exact test was used for the variables of classification results (p < 0.05 indicates that the difference is statistically significant).

Results

Common complications

The intraoperative and postoperative complications were summarized in Table 1, revealing a total of 37 cases (4.7%) in the TAPP group and 9 cases (3.5%) in the TEP group. There was no significant difference in the overall incidence of complications between the two groups. Specifically, there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of seroma, hematoma, incision infection, recurrences, chronic pain, and mesh infection between the two groups. The highest incidence of related complications was seroma, with 23 cases (2.93%) reported in the TAPP group and 2 cases (0.79%) in the TEP group. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Among the TAPP group patients with seroma, two were classified as Grade III (Clavien-Dindo) and required puncture and drainage. The remaining cases did not require special treatment. Hematoma was the next most common complication, with 5 cases (0.63%) in the TAPP group and 2 cases (0.79%) in the TEP group. One patient with TAPP had an incision infection, who was diabetic. Among the delayed complications, one patient with TEP had recurrences. No significant difference in the incidence of chronic pain between the two groups was found. There were no cases of mesh infection in either group.

Gastrointestinal complications

Five patients (0.48%) experienced gastrointestinal complications, summarized in Table 2. No significant difference between the two groups was observed. One patient underwent TEP and developed diffuse peritonitis on the second postoperative day, later discovered to be gastric perforation and repaired laparoscopically. The other four cases occurred in patients undergoing TAPP surgery, including a sliding hernia causing colon injury during electrotome separation, intestinal obstruction due to herniated small intestine into incompletely closed peritoneum, intestinal adhesion and torsion caused by excessive barbed suture tail length, and intestinal adhesion and obstruction because of a vascular ligation clip.

Discussion

Laparoscopic surgery can completely cover the muscle in the pubic foramen, and can obtain better surgical results compared with open surgery. However, it may also lead to rare but serious visceral injuries, especially in the TAPP surgery5,6, which may cause more visceral injuries, and these complications are sometimes fatal7,8. Such complications can occur in every step of the surgery, from the puncture needle entering the abdominal cavity, peritoneal exfoliation, extensive adhesiolysis, hernia reduction, sac excision, mesh fixation, and peritoneal closure to the end of the operation. These complications are usually related to the improper use of mesh, tacks, clips, staples, trocars, and barbed sutures.

Gastrointestinal injuries during the laparoscopic hernia surgery infrequently occur but can lead to serious consequences such as intestinal obstruction and fistula formation. These complications may result in an acute abdomen and often require urgent surgical intervention to prevent further damage. The overall duration of hospitalization and associated healthcare expenses for patients with this situation may increase considerably. Additionally, in certain instances, it can potentially result in fatal outcomes.

Bowel obstruction

The incidence of intestinal obstruction after LIHR is relatively rare, with an overall incidence of 0.102%-0.28%, 0.114%-0.5% for TAPP, and 0.028%-0.07% for TEP9,10,11. These findings indicated that TAPP increases the risk of postoperative intestinal obstruction compared with open surgery, while TEP does not increase significantly. Intestinal obstruction after laparoscopic hernia repair can be classified into hernia-related intestinal obstruction and adhesion-related intestinal obstruction based on the underlying causes. Hernia-related intestinal obstruction typically occurred around 8 days after the operation, whereas adhesion-related obstruction appeared approximately 25 days after the operation12.

Use of barbed suture

The most common cause of intestinal obstruction associated with hernia is herniation of the intestine into the incompletely closed or ruptured peritoneum, which is more common in TAPP surgery. Peritoneal closure is a challenging step in TAPP, and can be accomplished using various methods such as sutures, tacks, clips, staples, and strap devices. Among these, sutures are the most cost-effective option, but they require the highest level of surgical skill. Based on our experience, a sleigh-shaped needle can be used to suture from the right side of the peritoneal incision to the left side, with a needle distance of about 5 mm, which can shorten the suture time and is safe and effective. The rapid release of carbon dioxide at the end of an operation may cause a sudden pressure difference between the abdominal cavity and the preperitoneal space, potentially resulting in the enlargement of the suture peritoneal hiatus and the subsequent development of preperitoneal hernia, as believed by some scholars. We have taken some measures to avoid this situation. When the peritoneal valve was closed, the pneumoperitoneum pressure dropped to 8 to 10 mmHg. At the end of the operation, an aspirator was placed in the preperitoneal space through the peritoneal suture space to suck out the gas and a small amount of exudation in this space, and then the carbon dioxide in the abdominal cavity was slowly released. The incidence of intestinal obstruction after TEP was lower than that of TAPP, and was comparable to that after open surgery. The majority of cases are associated with peritoneal rupture during the operation.

Improper use of barbed sutures is a common cause of early adhesion-related intestinal obstruction after laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery. The barbed suture, which does not require knotting at the end of the suture, can repair peritoneal defects and significantly shorten operation time. In addition, the use of barbed sutures with self-anchoring capability is found to have superior strength compared to staples, absorbable tacks or extracorporeally knotted sutures. As a result, it is widely applied in digestive tract reconstruction, gynecological surgery, and other surgical procedures. However, it is noteworthy that improper use of barbed sutures can lead to serious complications. According to Guglielmo Stabile’s statistics, the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction in patients undergoing abdominal surgery using barbed suture during 2011–2020 was researched. In total, 6 out of 20 patients experienced this complication after hernia repair, accounting for 30% of all patients, followed by hysteromyomectomy (20%, n = 4)13. The high proportion undoubtedly warrants the attention of hernia surgeons.

During the operation, if the tail of the barbed sutures is too long, it can puncture the mesentery or intestine. Even if the retained tail of the barbed sutures is not extensive, the exposed sutures within the abdominal cavity will gradually elongate due to the intestinal tube’s peristalsis once they penetrate the intestinal wall. This may cause intestinal adhesion or volvulus, and eventually lead to intestinal obstruction. At this time, CT examination often shows volvulus or simple intestinal obstruction. According to most reports, conservative treatment is generally ineffective once mechanical intestinal obstruction and volvulus occur, and surgery is often necessary. In cases where the patient presents with acute abdominal symptoms that are related to barbed sutures, it is imperative that laparoscopy be performed as soon as possible. One of our patients suffered from intestinal obstruction after TAPP and had to be hospitalized again for surgery. During the operation, the indwelling barbed suture was found to be too long, which led to intestinal obstruction.

To prevent this situation, it is crucial to avoid direct contact between barbed sutures and the intestine. Any circumstance that leads to the exposure of the barbed sutures must be avoided, as clearly outlined in the manufacturer’s manual14. It is important to maintain proper suture spacing and moderate tension during the suture process to prevent exposure of the barb. Shortening thread tails and performing a few stitches backwards when ending a suture can ensure secure and neat closure of the wound. Additionally, walking a distance in the same direction in the peritoneum at the end of the suture and burying the tail of the suture in the medial umbilical fold may also be beneficial.

Use of spiral tack and ligation clips

It is also reported that some rare causes can lead to intestinal obstruction after laparoscopic hernia operation. Fitzgerald HL et al. reported a case of intestinal obstruction caused by a displaced spiral tack after TAPP. Spiral tacks were utilized during the surgery to fix the patch and close the peritoneum15. R. McKay reported that a patient experienced intestinal obstruction 48 h after TAPP surgery. Ligation clips were used during hernia repair to clamp the damaged peritoneum. During the reoperation, the intestinal canal had herniated into the peritoneal fissure between the two clips12. Another patient used surgical staples to fix the torn peritoneum during the TEP surgery, and developed intestinal obstruction 22 days after the operation. Upon re-operation, spiral tacks were found to be ectopic and had caused volvulus16.

One of the cases documented in our study indicated that during the surgical procedure, the omentum and small intestine were found adhered to the inguinal region. To control bleeding, a ligature clip was employed during the adhesiolysis; however, the adhesion between the intestine and omentum was not fully resolved. The patient experienced postoperative intestinal obstruction, which required reoperation 6 days after the initial operation. During the reoperation, the ligature clip had adhered to the intestine, causing the obstruction. Based on these experiences, it is recommended to exercise caution when using nails, clips, or other penetrating devices during peritoneal closure. Additionally, any medical apparatus and instruments that may come into contact with abdominal organs should be used with care.

Regrettably, the limited sample size prevented us from performing a meaningful statistical analysis on the occurrence of intestinal obstruction resulting from various surgical procedures. Nevertheless, our findings can serve as a valuable starting point for future research with larger sample sizes and more in-depth exploration of this crucial topic.

Bowel perforation

Intestinal injury is a rare but potential complication of LIHR. Intestinal injury may be indirectly caused by mesh infection and mesh displacement, or directly caused by the use of surgical instruments such as punctures and spiral tacks. Furthermore, the use of electrocautery during LIHR carries the potential risk of thermal tissue injury.

Use of electric knives

Sliding hernia and abdominal adhesions are frequently encountered in laparoscopic hernia repair. The operation on these patients is more complicated and requires more extensive adhesiolysis. However, extensive dissection during surgery inevitably increases the likelihood of intestinal damage. Especially the risk of inadvertent enterotomy (IE). Studies have shown that the overall incidence of intestinal rupture in complex abdominal hernia repair is 1.9%17.

The utilization of an electric knife can potentially result in the direct incision of the intestine or induce intestinal damage as a consequence of the thermal impact caused by the procedure. Although intestinal rupture was not observed during the operation, the occurrence of an intestinal fistula subsequently manifested post-surgery. Binenbaum SJ et al.18 show that 6 out of 312 patients who underwent inguinal hernia repair had inadvertent enterotomy. Among the 6 patients, 5 patients were found to have inadvertent enterotomy during the operation, and 1 patient underwent reoperation and was diagnosed with an unrecognized IE. Similarly, Swank DJ et al.19 document 11 instances of inadvertent enterotomy, among which 4 cases underwent reoperation and subsequently were diagnosed with unrecognized IE. Unfortunately, 1 of the 4 patients died the day after the second operation.

Therefore, the presence of visceral injury discovered intraoperatively necessitates prompt correction, with conversion to open treatment if deemed necessary, while the application of a mesh should be postponed17. To avoid the potential thermal effect caused by the electrotome on the intestine, scissors can be used to separate it near the intestine. At the same time, for patients with postoperative fever, abdominal pain, vomiting and other symptoms, abdominal X-ray or CT examination should be performed in time to rule out the possibility of intestinal injury.

In our study, a patient undergoing tapp surgery found adhesions between the sigmoid and the groin region during the procedure. Unfortunately, while trying to separate the adhesions, the electrotome accidentally injured the colon causing a rupture of the colon. Due to unforeseen circumstances, we were unable to place the mesh during the operation, and in addition to the high ligation of the hernia sac, we had to perform a colostomy. It also reminds us that the choice of surgical technique is crucial, especially when dealing with special cases, such as abdominal adhesions or slippery hernias.

Use of Veress needle and trocars

Veress needle and trocars have the potential to induce significant complications. While the rate of occurrence is relatively low, they can lead to severe visceral injury or damage to the vascular system20. Abdominal wall bleeding is a frequently encountered complication among these cases, whereas great vessel injury and intestinal injury are comparatively rare. It is worth mentioning that most studies exploring methods to mitigate these complications have excluded patients with a prior surgical history, resulting in limited case numbers and a lack of reliable data. Studies show that the puncture site bleeding and overall complications of blunt-tipped laparoscopic trocars are lower than those of bladed-tipped laparoscopic trocars. The incidence of puncture devices in the blunt-tipped laparoscopic trocars group stood at 3%, whereas the bladed laparoscopic trocar group experienced a higher incidence of 10%20,21.

Other complications

In our research, a patient returned to the doctor on the third day after TEP because of abdominal pain. He was suspected of having acute intestinal obstruction when he was admitted to the hospital. However, further tests indicated a perforation in the digestive tract. The patient took aspirin orally for a long time. Finally, it could be diagnosed that stress ulcer caused digestive tract perforation, and laparoscopic gastric perforation repair was conducted. Although there is evidence that it is safe to use antiplatelet agents in laparoscopic hernia repair, we recommend that acid suppression therapy be given to patients at high risk of developing digestive tract ulcers22.

The experience of this patient showed that all kinds of unexpected complications may occur during and after the operation. Once acute abdomen occurs after the operation, it is very important to make a clear, timeous, diagnosis to avoid misdiagnosis.

These observations may offer valuable insights and guidance for the creation and execution of treatment plans. However, our study has some limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The limited sample size included in the statistics hinders the possibility of conducting a detailed analysis on the intestine-related complications resulting from TAPP and TEP hernia repair techniques, especially when considering the vast number of operations performed worldwide annually. Furthermore, the follow-up period was relatively short, patients presenting with bowel erosion following inguinal hernia mesh repair often experience this complication several years, or even decades, after the initial surgery. Therefore, further research is essential to investigate this matter in greater depth.

Conclusion

The gastrointestinal complications of laparoscopic hernia repair may occur during all stages, from the insertion of the puncture needle into the abdominal cavity to the fixation of the patch and finally the closure of the peritoneum. Complications may occur due to inappropriate use of instruments, such as tacks, clips, staples, and barbed sutures during the operation. Reoperation is often necessary for most cases, and some complications can even be fatal. Although rare, complications such as intestinal obstruction and intestinal fistula after laparoscopic hernia repair should not be ignored due to the large number of operations performed worldwide each year. Attempting non-operative management of such complications may lead to disastrous consequences. To prevent these complications, it is important to have experienced surgeons perform the surgical treatment and ensure the appropriate selection and use of each instrument during the operation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Beard, J. H. et al. Outcomes after inguinal hernia repair with mesh performed by medical doctors and surgeons in Ghana. JAMA Surg. 154, 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.1744 (2019).

Potluri, T. et al. An estrogen-sensitive fibroblast population drives abdominal muscle fibrosis in an inguinal hernia mouse model. JCI Insight 7, e152011. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.152011 (2022).

McKernan, J. B. & Laws, H. L. Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias using a totally extraperitoneal prosthetic approach. Surg. Endosc. 7, 26–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00591232 (1993).

Sanford, Z. et al. Morgagni hernia repair: A review. Surg. Innov. 25, 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350618777053 (2018).

McCormack, K. et al. Transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair: A systematic review. Hernia J. Hernias Abdominal Wall Surg. 9, 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-004-0309-3 (2005).

Felix, E. L., Michas, C. A. & Gonzalez, M. H. Jr. Laparoscopic hernioplasty. TAPP vs TEP. Surg. Endoscopy 9, 984–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00188456 (1995).

Azevedo, J. L. et al. Injuries caused by Veress needle insertion for creation of pneumoperitoneum: A systematic literature review. Surg. Endoscopy 23, 1428–1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0383-9 (2009).

Schäfer, M., Lauper, M. & Krähenbühl, L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg. Endoscopy 15, 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004640000337 (2001).

Bringman, S. & Blomqvist, P. Intestinal obstruction after inguinal and femoral hernia repair: A study of 33,275 operations during 1992–2000 in Sweden. Hernia J. Hernias Abdominal Wall Surg. 9, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-004-0305-7 (2005).

Sartori, A. et al. Rare intraoperative and postoperative complications after transabdominal laparoscopic hernia repair: Results from the multicenter wall hernia group registry. J. Laparoendoscopic Adv. Surg. Tech. Part A 31, 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2020.0459 (2021).

Thalheimer, A., Vonlanthen, R., Ivanova, S., Stoupis, C. & Bueter, M. Mind the gap—Small bowel obstruction due to preperitoneal herniation following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair—A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 88, 106532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106532 (2021).

McKay, R. Preperitoneal herniation and bowel obstruction post laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: Case report and review of the literature. Hernia J. Hernias Abdominal Wall Surg. 12, 535–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-008-0341-9 (2008).

Stabile, G. et al. Case report: Bowel occlusion following the use of barbed sutures in abdominal surgery. A single-center experience and literature review. Front. Surg. 8, 626505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.626505 (2021).

Filser, J. et al. Small bowel volvulus after transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair due to improper use of V-Loc™ barbed absorbable wire - do we always “read the instructions first”?. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 8c, 193–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.02.020 (2015).

Fitzgerald, H. L., Orenstein, S. B. & Novitsky, Y. W. Small bowel obstruction owing to displaced spiral tack after laparoscopic TAPP inguinal hernia repair. Surg. Laparoscopy Endoscopy Percutaneous Tech. 20, e132-135. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181dfbc05 (2010).

Withers, L. & Rogers, A. A spiral tack as a lead point for volvulus. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendoscopic Surg. 10, 247–249 (2006).

Krpata, D. M. et al. Impact of inadvertent enterotomy on short-term outcomes after ventral hernia repair: An AHSQC analysis. Surgery 164, 327–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2018.04.003 (2018).

Binenbaum, S. J. & Goldfarb, M. A. Inadvertent enterotomy in minimally invasive abdominal surgery. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendoscopic Surg. 10, 336–340 (2006).

Swank, D. J. et al. Complications and feasibility of laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain. A retrospective study. Surg. Endoscopy 16, 1468–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-002-0008-z (2002).

Ahmad, G., Baker, J., Finnerty, J., Phillips, K. & Watson, A. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD006583. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006583.pub5 (2019).

Antoniou, S. A., Antoniou, G. A., Koch, O. O., Pointner, R. & Granderath, F. A. Blunt versus bladed trocars in laparoscopic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Surg. Endoscopy 27, 2312–2320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-2793-y (2013).

Balch, J. A. et al. Safety of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in the setting of antithrombotic therapy. Surg. Endoscopy 36, 9011–9018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09360-1 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank each patient and their families for their participation and allow us to publish this report.

Funding

This study was funded by Shanxi Province “136 Revitalization Medical Project Construction Funds”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Y. and Y.W. contributed equally to this work. Y.W. designed the research and provided critical revision of the article. B.Y. and Y.L. collected and analyzed patients' data and wrote this article. C.X.and Y.L. discussed the clinical features of the patients.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, B., Xie, CH., Lv, YX. et al. Rare but important gastrointestinal complications after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a single-center experience. Sci Rep 15, 2593 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87188-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87188-0