Abstract

To explore the associations of central obesity indicators including waist circumference (WC), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), and weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) with the impairment of basic activities of daily living (BADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) among middle-aged and elderly population in China. This prospective study used baseline data from 2011 and follow-up data, involving 6440 and 9646 participants, respectively. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to assess the relationships. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) curve was also used to analyze the correlation trends. Stratified analyses were performed to identify potential differences. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted to evaluate the predictive value of each indicator. WC (OR = 1.01, 95% CI:1.01–1.02), WHtR (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.09–1.33), and WWI (OR = 1.10, 95% CI:1.02–1.19) were significantly associated with BADL impairment. Only WWI (OR = 1.16, 95%CI:1.09–1.23) was associated with IADL impairment. WC, WHtR and WWI were linearly associated with BADL impairment while WWI was linearly associated with IADL impairment. The risk association between WWI and BADL was stronger in drinking individuals and males. In the participants with a BMI less than 24 kg/m² and who had received a high school education or above, the increase in WWI was accompanied by a more significant risk of IADL impairment. The predictive ability of WWI is higher than that of WC and WHtR, with AUC values of 0.597 and 0.615. WWI, as a comprehensive indicator of central obesity, may be useful in comprehensively identifying the risk of early daily living activity impairment among middle-aged and elderly population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing aging of the global population has emerged as an irrefutable trend, bringing ongoing difficulties to public health systems globally. The issue of China’s aging population has gained greater visibility in light of its tremendous economic growth. The projected increase in the percentage of adults aged 60 and beyond in China will double from 15% in 2015 to 30% by 20501. In middle-aged and elderly individuals, the process of aging is frequently accompanied by reduction in physical abilities and the emergence of health problems, including diminished muscular strength, reduced joint flexibility, cognitive alterations, and metabolic diseases. These disorders can impede peoples’ capacity to carry out activities of daily living (ADL), which are frequently employed to evaluate functional limitations2. ADL assessments include evaluations of both basic activities of daily living (BADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). BADL denotes the ability to perform basic self-care activities, including feeding, hygiene, and mobility, without external assistance. IADL encompass increasingly intricate tasks essential for self-sufficient functioning within the community, including shopping, housework, and medication administration3. Impairments in BADL or IADL are often considered critical indicators of functional disability in the elderly, leading to a decrease in quality of life and an increase in healthcare costs4. Previous studies have highlighted the potential impact of ADL on health and quality of life, linking high ADL risk to diseases such as depressive symptoms5, sleep disorders6, and hypertension7. The identification of high-risk populations and the development of potential intervention strategies can be facilitated by the investigation of factors that are associated with an increased risk of functional impairment.

Obesity has become a significant risk factor leading to chronic diseases and a reduced quality of living. Excessive body weight increases physical burden, making daily activities slow and strenuous8. Central obesity particularly leads to various chronic diseases, including metabolic disorders and hypertension, further limiting physical capacity and endurance in daily activities, resulting in functional impairments9. In recent years, waist circumference (WC) has been proposed as a more reliable indicator of obesity-related disease risk10, as WC measurement more accurately reflects abdominal fat distribution and visceral obesity, with less influence from overall muscle mass11. However, WC fails to include variations in height, which might potentially lead to biased risk assessment among individuals of various heights12. In order to address this issue, some researchers have introduced the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and demonstrated its superior performance over WC in predicting cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes mellitus (DM)12. The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) is a newly introduced anthropometric measure, obtained by standardizing WC by weight. WWI reflects both fat and muscle mass composition, with higher WWI scores indicating higher levels of obesity13. WWI has been shown to effectively predict the risk of cardiometabolic diseases and mortality13. Recent studies have also found significant associations between WWI and type 2 DM14, cognitive impairment15, frailty16, and hypertension17.

However, there has been no prospective study conducted to evaluate the associations between central obesity indicators (WC, WHtR, and WWI) and BADL or IADL impairment in middle-aged and elderly populations (aged ≥ 45 years). Therefore, this study focuses on middle-aged and elderly populations, utilizing data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) to comprehensively evaluate the stable associations of WC, WHtR, and WWI with BADL or IADL, thereby providing evidence to support central obesity management strategies for preventing ADL impairment.

Methods

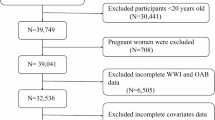

Study population

CHARLS is a nationwide survey sponsored by the National School of Development at Peking University and conducted by the Peking University Institute of Social Science Survey. This study aims to collect comprehensive data on Chinese adults aged 45 and older, covering a wide range of aspects such as health status, healthcare utilization, personal experience, economic conditions, and family structure. The survey was conducted in 2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2020 across 28 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities), 150 counties, and 450 communities (villages). All participants provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. This research was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015)18. In this study, the analyzed data were obtained from the 2011 to 2020 CHARLS data set. Participants were excluded if they met the following criteria: (1) age below 45; (2) missing BADL or IADL data; (3) missing data on weight, WC, or height; (4) missing demographic data; (5) participants with WC extreme values (WC < 40 cm or WC > 150 cm)19. The prospective study used baseline data from 2011 and follow-up data from 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2020, including 6440 and 9646 participants, respectively.

BADL/IADL impairment assessment

In this study, physical function was assessed using the ADL scale, which includes both BADL and IADL components. Each item on the scale has four response options: “no difficulty,” “some difficulty but can still perform,” “difficulty and needs help,” and “unable to perform”20. The ADL scale has been extensively utilized in both domestic and international research and has consistently shown strong reliability and validity in evaluating functional impairment. BADL comprises six aspects of personal care, including dressing, bathing, eating, getting out of bed, toileting, and incontinence. IADL consists of six tasks: housekeeping, cooking, shopping, medication management, using the telephone, and managing finances. Based on previous research findings, a dichotomous approach was adopted for the analysis: inability to independently perform any BADL or IADL task was defined as BADL or IADL impairment21.

Measurement of WC, WHtR and WWI

Following the acquisition of informed consent, proficient experts carried out meticulous assessments for each participant, encompassing measures of height (in meters), weight (in kilograms), and waist circumference (in centimeters). Participants’ height was measured in an upright position and without wearing shoes, using accurate tools. The weight was measured precisely, with participants taking off their shoes and heavy coats to eliminate any extra weight and ensure accuracy. WC was measured with participants standing and removing heavy clothing. A tape measure was positioned at the level of the umbilicus, and the measurement was recorded at the conclusion of exhalation to ensure accuracy. In order to conduct a more thorough analysis of the correlation between central obesity and ADL impairment, some crucial indicators were computed. WHtR was calculated by dividing WC by height, incorporating body shape into the assessment of central obesity. Finally, the WWI was derived by dividing WC by the square root of weight, reflecting excessive body fat buildup and the loss of muscular mass.

Covariates

Self-reported questionnaires were used to gather covariate data, which included sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, educational level, marital status, residence, smoking, and drinking. Specifically, educational level was divided into three categories: primary school or below, middle/high school, and college or above. Marital status was classified as married or unmarried. Residence was categorized as urban or rural. Smoking status was classified as no or yes based on current smoking status, while drinking was divided into no or yes based on current alcohol status. Age was categorized into two groups, 45–64 years and 65 years or older in the subgroup analysis and BMI was divided into two groups based on whether it is greater than or equal to 24 kg/m2.

Health status assessment

Hypertension diagnosis was based on physician diagnosis. The diagnostic criteria for DM included any of the following: fasting blood glucose ≥ 7 mmol/L, random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, glycated hemoglobin ≥ 6%, or physician-confirmed diagnosis22. Dyslipidemia was diagnosed based on any of the following criteria: total cholesterol ≥ 6.2 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥ 4.1 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥ 2.3 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <1 mmol/L, or physician-confirmed diagnosis23.

Statistical strategy

Participants were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of BADL or IADL impairment respectively. Mean ± standard deviation was used to represent continuous variables, whereas percentages were used to express categorical variables. Between-group differences were assessed using T-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. In order to examine the relationships between WC, WHtR, WWI and BADL/IADL impairment, multivariable logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI). To control for potential covariates, models were adjusted sequentially: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, and BMI; Model 2 further adjusted for smoking, drinking, residence, marital status, and educational level; Model 3 additionally adjusted for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and DM. Subsequently, the results of the models before and after adjustment were visualized. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) was performed find the trend of change, and subgroup analyses were conducted based on sex, marital status, residence, smoking, drinking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM, BMI, and age using logistic regression. Bonferroni correction was performed in subgroup analysis with significant interaction effects. Finally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to evaluate the diagnostic value of each indicator. In the continuous models, RCS, and subgroup analysis, WHtR was multiplied by a factor of 10 to facilitate the interpretation of OR. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and all statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.1.

Result

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents the distribution of participants in the prospective study and the baseline comparison. The results indicated that 1,496 participants experienced BADL impairment during the follow-up period. Compared to participants without BADL impairment, those with BADL impairment were generally older, female, unmarried, had lower educational attainment, were more likely to have hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM and had higher WC, WHtR, and WWI. Additionally, 3,969 participants experienced IADL impairment. Compared to those without IADL impairment, participants with IADL impairment were generally older, female, unmarried, had lower educational attainment, lived in rural areas, did not smoke and drink, and had a higher likelihood of hypertension and DM. Although their weight and BMI were lower, their WHtR and WWI values were higher compared to those without IADL impairment.

Association of WC, WHtR, WWIwith ADL impairment in the prospective study

Table 2 shows the associations between WC, WHtR, WWI and the incidence of BADL impairment in the prospective study, based on logistic regression models. In the unadjusted model, WC (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.01–1.02), WHtR (OR = 1.38, 95%CI = 1.27–1.50), and WWI (OR = 1.47, 95%CI: 1.38–1.57) were significantly associated with a higher risk of BADL impairment. After adjusting for variables, WC (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.01–1.02), WHtR (OR = 1.21, 95%CI = 1.09–1.33), and WWI (OR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.02–1.19) remained significantly associated with BADL impairment risk. Additionally, when converting continuous variables into categorical variables, participants in the highest quartiles of WC (OR = 1.36, 95%CI: 1.13–1.64), WHtR (OR = 1.30, 95%CI = 1.07–1.58), and WWI (OR = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.03–1.53) exhibited a higher risk of BADL impairment compared to those in the lowest quartiles (Fig. 1A). Analyses based on standard deviations and interquartile ranges further confirmed a significant positive association between WC, WHtR, WWI and BADL impairment.

Table 3 presents the relationships between WC, WHtR, WWI and IADL impairment in the prospective study. According to the unadjusted model, WHtR (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.21–1.37) and WWI (OR = 1.65, 95%CI: 1.57–1.74) were significantly associated with a higher risk of IADL impairment, while WC was not. After adjusting for covariates, only WWI (OR = 1.16, 95%CI = 1.09–1.23) remained associated with IADL impairment. Further analysis by quartiles indicated that participants in the highest quartile of WWI (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.12–1.49) had a significantly increased risk of IADL impairment compared to those in the lowest quartile (Fig. 1B). Standard deviation and interquartile range analysis demonstrated that WC and WHtR were not significantly associated with IADL impairment, while WWI maintained a positive correlation with IADL impairment.

Logistic regression trend plot of the relationship between WC, WHtR, WWI and ADL impairment. A, Binary logistic regression trend plot of the relationship between WC, WHtR, WWI and BADL impairment. B, Binary logistic regression trend plot of the relationship between WC, WHtR, WWI and IADL impairment. OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; Q1, quartile 1; Q2, quartile 2; Q3, quartile 3; Q4, quartile 4.

RCS analysis in the prospective study

As shown in Fig. 2, the RCS results suggest there was a linear relationship between WC, WHtR, WWI and BADL impairment risk. Similarly, Fig. 3 indicates a linear correlation between WWI and IADL impairment risk.

RCS curves for WC, WHtR and WWI associated with BADL impairment after adjusting age, sex, smoking, drinking, residence place, marital status, education, hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM. A, RCS curve of WC related to BADL impairment; B, RCS curve of WHtR related to BADL impairment; C, RCS curve of WWI related to BADL impairment.

Subgroup analysis in the prospective study

Figure 4 presents the associations between WC, WHtR, WWI and the risk of BADL impairment across different subgroups, including sex, age, BMI, drinking, smoking, marital status, residence, DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Most subgroups did not significantly affect these associations after adjusting for covariates. However, WWI showed a stronger association with the risk of BADL impairment among individuals who consumed alcohol and males.

Figure 5 displays the associations between WWI and the risk of IADL impairment in various subgroups after adjusting for covariates. The results showed that among the participants with a BMI less than 24 kg/m² and who had received a high school education or above, the increase in WWI was accompanied by a more significant risk of IADL impairment.

Forest plot of the relationship between WC, WHtR, WWI and BADL impairment in different subgroups after adjusting age, sex, smoking, drinking, residence place, marital status, education, hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM. A, Forest plot of the relationship between WC and BADL impairment in different subgroups; B, Forest plot of the relationship between WHtR and BADL impairment in different subgroups; C, Forest plot of the relationship between WWI and BADL impairment in different subgroups. OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

ROC curve of WC, WHtR and WWI on ADL impairment

ROC curve analysis is used to evaluate the diagnostic value of WC, WHtR and WWI in predicting ADL impairment. As shown in Fig. 6, the area under the curve (AUC) of the three indicators reflecting central obesity was greater than 0.5, indicating their potential in identifying ADL risk. It is worth noting that the predictive ability of WWI is higher than WC and WHtR, with AUC values of 0.597 and 0.615, respectively in BADL and IADL impairment.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between central obesity indicators (WC, WHtR and WWI) and BADL and IADL impairment in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. The results showed that higher levels of WC, WHtR and WWI significantly increased the risk of BADL impairment and the increase of WWI effectively reflected the increased risk of IADL impairment. These findings emphasize that central obesity, particularly as measured by WWI, may significantly affect functional health in middle-aged and older populations. This implies that greater emphasis should be placed on the use of WWI in health screening and risk assessment.

IADL and BADL are recognized as having a hierarchical longitudinal relationship24. IADL reflects initial stages of impairment, encompassing cognitive and social skills, while BADL represents an individual’s ability to perform basic daily activities, showing a more pronounced level of physical disability25. The risk of ADL impairment increases with age among obese individuals8. However, the relationship between obesity and the risk of physical impairment is not a simple linear one, and the risk of obesity leading to physical impairment remains controversial26. Some studies suggest that BMI may be a protective factor against ADL impairment27, while BMI is not a reliable measure of the ratio of fat to muscle, resulting in conflicting findings28. Thus, depending merely on BMI may be inadequate for evaluating the dangers linked to early central obesity and may fail to identify a segment of the potentially high-risk population29. Although the overall obesity indicators among the elderly population in China are relatively stable, the risks associated with central obesity are increasing30. Patterns of central obesity trajectories are closely related to changes in CVD risk, even among individuals who are not overweight, and this association is more pronounced in younger individuals31. Central obesity is believed to be associated with risks of dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and metabolic abnormalities32. WC is commonly used to assess the degree of abdominal fat accumulation and central obesity, and the association between WC and ADL impairment has been confirmed among the elderly population in China33. WHtR is the ratio of WC to height, which not only considers the absolute value of waist circumference but also accounts for the influence of height, thereby reducing the biases in obesity assessment due to body shape. Research has demonstrated that WHtR is particularly reliable in reflecting the degree of visceral fat34, and higher WHtR is closely related to the risks of dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular diseases35. A survey of 1,453 adults in the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008–2012) showed that compared to a complex combination of BMI and WC boundary values, a WHtR greater than 1/2 can identify more individuals at early health risk, while a WHtR greater than 0.6 is considered to be at high risk of obesity-related health issues35. WHtR can serve as a simpler and more predictive indicator of early cardiovascular health risks related to central obesity29.

IADL involves more complex cognitive and daily tasks, while BADL focuses on basic self-care abilities. The prospective study shows that WC and WHtR are only significantly associated with the risk of BADL impairment and not with IADL. This could be attributed to the fact that higher WC and WHtR may limit the range of motion and flexibility, making movements like bending and turning difficult, thereby affecting BADL activities such as dressing and personal hygiene. Additionally, excessive abdominal fat may increase the body’s burden and exert continuous pressure on the musculoskeletal system, affecting basic mobility. Furthermore, the abdominal obesity and metabolic abnormalities represented by WC and WHtR have cumulative effects on physical function, especially since metabolic diseases have long-term negative impacts on BADL. In contrast, IADL impairment involves complex cognitive and interpersonal abilities, which are more likely to be influenced by factors such as cognitive reserve, social support, education level, or other non-metabolic factors. These complex factors may partially buffer the long-term impact of fat distribution on IADL, thus underestimating the influence of WC and WHtR on IADL36.

WWI is an indicator that integrates weight and WC information, and higher WWI may indicate a higher body fat percentage. WWI enhances the association with WC while weakening the association with weight, thus more comprehensively reflecting fat distribution and muscle mass37. As a novel indicator explaining central obesity, WWI is more reliable than WC and WHtR in predicting CVD and all-cause mortality in diabetic patients38. Changes in fat and muscle mass are closely related to the decline in physical function, with fat content being positively correlated with impairment39. The decrease in muscle mass is often accompanied by an increase in body fat, especially among middle-aged and elderly population, and the combined changes of these two may more directly reflect the risk of functional impairment40. Research has demonstrated that dynapenic abdominal obesity is associated with an increased likelihood of ADL impairment in the elderly41. Moreover, through a stacked ensemble model, waist circumference has been determined to be a highly significant predictor of ADL impairment42. A cross-sectional study from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey showed that among the elderly population (aged over 65 years), BMI was not associated with ADL impairment, while WWI was positively correlated with fat content and negatively correlated with weight, indicating that it is an excellent indicator reflecting the risk of obesity-related ADL impairment40.

Compared to WHtR and WC, WWI is not only an indicator of weight management but is also related to overall metabolic status, muscle mass, and long-term changes in cognitive function15. Long-term obesity can affect not only physical activity but also brain function over time through mechanisms such as chronic inflammation, metabolic disorders, and impaired blood flow, gradually leading to cognitive decline and thus a decrease in IADL43. In the prospective studies, WWI shows a significant linear correlation with dysfunction in both BADL and IADL. This indicates that WWI, as a comprehensive indicator, has the potential to capture early signals of both basic instrumental activities impairments, making it advantageous in reflecting overall health status and predicting ADL functional decline at an earlier stage.

The data in this study were measured by trained professionals, reducing the bias brought by self-reporting. Additionally, this study provides a relatively comprehensive analysis of the relationship between central obesity indicators (WC, WWI, and WHtR) and BADL and IADL, with a particular focus on the association between central obesity and ADL impairment in the middle-aged population. Compared to WC and WHtR, WWI not only helps identify the risk of functional decline in middle-aged and elderly population but can also be used in daily health screening and risk assessment, indicating its potential application value in clinical evaluation.

Limitation

However, this study has some limitations. The study sample failed to capture the dynamic changes of the indicators, and there is a lack of control of confounding factors that may affect the results, such as physical activity, diet, mental state, and medication use. This may affect the accuracy of the analysis results.

Although the ROC analysis demonstrated that WWI has predictive ability for ADL impairment, this predictive power is relatively insufficient. This observation aligns with previous epidemiological studies40. Notably, our findings establish WWI as a clinically accessible predictor that may serve as foundational element for composite risk models. Future research can further explore machine learning algorithms (such as random forest and gradient boosting tree) or hierarchical modeling strategies, and improve the prediction accuracy by optimizing feature selection and combination, such as incorporating age, lifestyle, physical activity, diet, psychological state and metabolic indicators. Through multidimensional analysis, we can better understand the mechanisms by which central obesity contributes to functional health decline and provide more precise and early health management strategies for middle-aged and elderly population.

Despite certain limitations in the findings of this study, it can still offer valuable references for policy - making and public health interventions. In the field of public health management, the potential role of indicators such as WC, WHtR, and WWI in assessing the activities of daily living ability of the population should be emphasized. It is recommended to incorporate these indicators into the routine health monitoring system. Moreover, efforts should be made to actively promote the implementation of weight management programs suitable for different groups at the grassroots level, so as to prevent and reduce the incidence of ADL impairments.

Conclusion

WC, WHtR, WWI are all associated with BADL impairment while only WWI is significantly associated with IADL impairment among middle-aged and elderly population in China. WWI, as a comprehensive indicators of central obesity, may be useful in comprehensively identifying the risk of early ADL impairment among middle-aged and elderly population.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/).

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BADL:

-

Basic activities of daily living

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHARLS:

-

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- 95%CI:

-

95% Confidence interval

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- IADL:

-

Instrumental activities of daily living

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHtR:

-

Waist-to-height ratio

- WWI:

-

Weight-adjusted waist index

References

Zhong, Y., Wang, J. & Nicholas, S. Gender, childhood and adult socioeconomic inequalities in functional disability among Chinese older adults. Int. J. Equity Health. 16, 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0662-3 (2017).

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A. & Jaffe, M. W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of Adl: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185, 914–919. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 (1963).

Zhou, L., Wang, W. & Ma, X. The bidirectional association between the disability in activities of daily living and depression: a longitudinal study in Chinese middle-aged and older adults. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1884. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19421-w (2024).

Johnston, K. J., Wen, H., Hockenberry, J. M. & Joynt Maddox, K. E. Association between patient cognitive and functional status and medicare total annual cost of care: implications for Value-Based payment. JAMA Intern. Med. 178, 1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4143 (2018).

Yan, Y., Du, Y., Li, X., Ping, W. & Chang, Y. Physical function, ADL, and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly: evidence from the CHARLS. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1017689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1017689 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. The relationship between sleep duration and activities of daily living (ADL) disability in the Chinese oldest-old: A cross-sectional study. PeerJ 11, e14856. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14856 (2023).

Sugimoto, K. & Yamamoto, K. Hypertension, the decline of activities of daily living (ADL) and frailty. Hypertens. Res. 45, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00846-4 (2022).

Fayosse, A. et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of obesity with disability between age 50 and 90 in the SHARE study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 119, 105320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.105320 (2024).

Barbosa, F. S. Abdominal obesity and mobility disability in older adults: A 4-Year Follow-Up the international mobility in aging study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 22, 1228–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1100-y (2018).

Wang, N., Li, Y. & Guo, C. Waist-corrected BMI predicts incident diabetes mellitus in a population-based observational cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1186702. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1186702 (2023).

Gomez-Ambrosi, J. et al. Body mass index classification misses subjects with increased cardiometabolic risk factors related to elevated adiposity. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 36, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2011.100 (2012).

Browning, L. M., Hsieh, S. D. & Ashwell, M. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0.5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr. Res. Rev. 23, 247–269. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422410000144 (2010).

Park, Y., Kim, N. H., Kwon, T. Y. & Kim, S. G. A novel adiposity index as an integrated predictor of cardiometabolic disease morbidity and mortality. Sci. Rep. 8, 16753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35073-4 (2018).

Li, X., Zhao, D. & Wang, H. Association between weight-adjusted waist index and risk of diabetes mellitus type 2 in United States adults and the predictive value of obesity indicators. BMC Public Health 24, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19576-6 (2024).

Qiu, X., Kuang, J., Huang, Y., Wei, C. & Zheng, X. The association between Weight-adjusted-Waist index (WWI) and cognitive function in older adults: a cross-sectional NHANES 2011–2014 study. BMC Public. Health. 24, 2152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19332-w (2024).

Luo, J. et al. The weight-adjusted waist index and frailty: A cohort study from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 28, 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100322 (2024).

Huang, X., Huang, Y., Zhou, H. & Huang, Z. Relationship between weight-adjusted-waist index and blood pressure as well as incident hypertension among middle-aged and elderly Chinese: A longitudinal study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 34, 2095–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2024.06.006 (2024).

Sha, T., Cheng, W. & Yan, Y. Prospective associations between pulse pressure and cognitive performance in Chinese middle-aged and older population across a 5-year study period. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 10, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0355-1 (2018).

Du, P. et al. Prevalence of abdominal obesity among Chinese adults in 2011. J. Epidemiol. 27, 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2017.03.001 (2017).

Jin, X. et al. Associations between household solid fuel use and activities of daily living trajectories: A nationwide longitudinal study of middle and older adults in China. Environ. Int. 170, 107605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107605 (2022).

Feng, Z., Li, Q., Zhou, L., Chen, Z. & Yin, W. The relationship between depressive symptoms and activity of daily living disability among the elderly: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Public. Health. 198, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.06.023 (2021).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice. C. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 45, S17-S38, (2022). https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S002

Li, J. J. et al. Chinese guideline for lipid management. Front Pharmacol 14, 1190934, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1190934 (2023).

Barberger-Gateau, P., Rainville, C., Letenneur, L. & Dartigues, J. F. A hierarchical model of domains of disablement in the elderly: a longitudinal approach. Disabil. Rehabil. 22, 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/096382800296665 (2000).

Royall, D. R. et al. The cognitive correlates of functional status: a review from the committee on research of the American neuropsychiatric association. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 19, 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.2007.19.3.249 (2007).

Rejeski, W. J., Marsh, A. P., Chmelo, E. & Rejeski, J. J. Obesity, intentional weight loss and physical disability in older adults. Obes. Rev. 11, 671–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00679.x (2010).

Nair, S., Chen, S., Gupta, D., Smith, A. J. & McGregor, A. L. Higher BMI confers a Long-Term functional status advantage in elderly new Zealand European stroke patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 30, 105711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105711 (2021).

Antonopoulos, A. S., Oikonomou, E. K., Antoniades, C. & Tousoulis, D. From the BMI paradox to the obesity paradox: the obesity-mortality association in coronary heart disease. Obes. Rev. 17, 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12440 (2016).

Ashwell, M. & Gibson, S. Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of ‘early health risk’: simpler and more predictive than using a ‘matrix’ based on BMI and waist circumference. BMJ Open. 6, e010159. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010159 (2016).

Lao, X. Q. et al. Overall obesity is leveling-off while abdominal obesity continues to rise in a Chinese population experiencing rapid economic development: analysis of serial cross-sectional health survey data 2002–2010. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 39, 288–294. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.95 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. A prospective study of waist circumference trajectories and incident cardiovascular disease in China: the Kailuan cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa331 (2021).

Despres, J. P. & Lemieux, I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 444, 881–887. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05488 (2006).

Yang, M., Jiang, J., Li, H., Wu, H. & Dong, B. Association between waist circumference and self-reported disability among Chinese adults aged 90 years and older. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 15, 1249–1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12424 (2015).

Roriz, A. K. et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of anthropometric clinical indicators of visceral fat in adults and elderly. PLoS One. 9, e103499. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103499 (2014).

Alshamiri, M. Q. et al. Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR) in Predicting Coronary Artery Disease Compared to Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference in a Single Center from Saudi Arabia. Cardiol Res Pract 4250793, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4250793 (2020).

Ping, R. & Oshio, T. Education level as a predictor of the onset of health problems among China’s middle-aged population: Cox regression analysis. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1187336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1187336 (2023).

Zeng, P., Jiang, C., Cao, J., Li, M. & Lin, F. Longitudinal relationship between weight-adjusted waist index and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: A prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 363, 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.07.080 (2024).

Tao, Z., Zuo, P. & Ma, G. The association between weight-adjusted waist circumference index and cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes. Sci. Rep. 14, 18973. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69712-w (2024).

Hussain, S. M. et al. Fat mass and fat distribution are associated with low back pain intensity and disability: results from a cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 19, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1242-z (2017).

Sun, J. et al. Associations of body mass index, waist circumference and the weight-adjusted waist index with daily living ability impairment in older Chinese people: A cross-sectional study of the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 4069–4077. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15762 (2024).

Smith, L. et al. Dynapenic abdominal obesity and activities of daily living disability among older adults residing in low- and middle-income countries. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36, 212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02864-x (2024).

Yu, Q. et al. Predicting functional dependency using machine learning among a middle-aged and older Chinese population. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 115, 105124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.105124 (2023).

Whitmer, R. A., Gunderson, E. P., Barrett-Connor, E., Quesenberry, C. P. Jr. & Yaffe, K. Obesity in middle age and future risk of dementia: a 27 year longitudinal population based study. BMJ 330, 1360. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38446.466238.E0 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the subjects who participated in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the High Level Chinese Medical Hospital Promotion Project (NO.HLCMHPP2023082, NO.HLCMHPP2023011) and The Science and Technology Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (NO.CI2023C007YG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YD and WZ conceived and designed the study. YD, XZ conducted data organization and analysis. YD, XZ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. YW and WZ polished the English. YH and YW revised the manuscript and contributed to the conception and design of this article. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors listed approved it for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This research was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015). All participants were informed for the protocol of study and signed informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal.

relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Y., Zhang, W., Zhang, X. et al. Association between central obesity and ADL impairment among the middle-aged and elderly population in China based on CHARLS. Sci Rep 15, 13455 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95273-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95273-7