Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and insomnia are the two most common sleep disorders. The coexistence of these conditions, termed comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA), has been increasingly recognized, with evidence suggesting a bi-directional relationship that exacerbates the severity of each disorder. This prospective recruited 170 consecutive patients with OSA, categorized into OSA alone and COMISA group. Among recruited patients, 68 (40%) were identified with COMISA. No significant differences were found in age, gender, or body mass index between COMISA and OSA alone groups. However, COMISA patients were more likely to have comorbid medical conditions, reported worse sleep quality, and exhibited higher levels of anxiety and depression. Sleep architecture and the distribution of the low arousal threshold endotype, a potential contributor to COMISA, did not significantly differ between patients with COMISA and OSA alone. Our results suggest that COMISA is prevalent among Asian patients with OSA and is associated with worse subjective sleep quality, adverse health conditions, and higher psychological distress. However, objective sleep architecture and arousal threshold endotypes do not significantly differ from OSA alone. Further research is needed to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying COMISA and optimize treatment approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and insomnia are the two most common sleep disorders. In recent years, the relationship between these two conditions has garnered increasing recognition within academic and clinical communities1. OSA involves recurrently transient closures (apnea) or narrowing (hypopnea) of the upper airway during sleep, leading to reduced oxygen levels, frequent arousals during sleep, and heightened sympathetic nervous system activities2. Insomnia, on the other hand, is characterized by dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity, accompanied by difficulty falling or maintaining asleep3. Both OSA and insomnia are recognized as being associated with increased risks of morbidity and mortality2,3.

Initially, OSA and insomnia were considered distinct sleep disorders. However, in the early 1970s, Guilleminault and colleagues introduced the concept of “insomnia with sleep apnea”, proposing that there might be a functional association between insomnia symptoms and apnea4. They suggested that respiratory function during sleep should be assessed in insomnia patients with frequent conscious arousals and heavy snoring .

Despite the early insight, this relationship between OSA and insomnia received little attention until the 21th centruy. Studies have revealed a high prevalence of OSA among patients with insomnia, and vice versa5,6. The concept of “comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea” (COMISA) was re-introduced by Sweetman and colleagues in 20177. Evidence indicates that patients with COMISA may experience not only reduced daytime functioning and diminished quality of life but also a higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared to those with either OSA or insomnia alone6,8,9,10,11. It is suggested that the two disorders maintain a bidirectional relationship1.

To date, the differences between OSA and COMISA patients in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, and polysomnography (PSG) features remained inconsistent. While previous studies have suggested that COMISA patients may tend to be older, female, and have a lower body mass index (BMI) than those with OSA alone6,12,13, substantial evidence has yet to identify significant differences in age, gender, or other sociodemographic characteristics14,15.

In addition to a higher prevalence of medical comorbidities, studies have demonstrated that patients with COMISA report higher rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental illnesses compared to patients with OSA alone5,16,17,18. However, a controlled study conducted in the United States found no association between COMISA and physician-rated psychiatric syndromes13. Moreover, the literature presents inconsistent findings when comparing sleep structure parameters derived from PSG between patients with COMISA and OSA alone. Some studies reported that COMISA patients exhibit lower apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE), and more sleep stage transition, along with significantly longer wake-after sleep onset (WASO) than OSA patients15,19. In contrast, Lichstein and colleagues found no statistically significant differences in sleep structure parameters between patients with COMISA and OSA alone14. Other studies also reported no differences in AHI, SE, and WASO between these two groups20.

Previous studies, primarily conducted on selected samples in Western countries, employing diverse methodologies, have yielded inconsistent results. The earlier study in Taiwan included only male subjects17. The inconsistencies may be partly attributed to racial and ethnic differences, selection bias, and the varying definitions used to identify OSA, insomnia, and COMISA. Furthermore, controversial findings regarding objective sleep architecture assessed by traditional PSG parameters suggest a need for a more detailed analysis of these biosignals21,22. It has been proposed that examining different OSA endotypes, particularly the low arousal threshold, may reveal important features distinguishing COMISA from OSA and insomnia23. The low arousal threshold may cause abrupt shifts to higher EEG frequencies in response to increased respiratory resistance resulting from the narrowing of the upper airway during sleep and simultaneously cause sleep fragmentation. This pathophysiological mechanism can operate bi-directionally, contributing to insomnia patients with OSA and potentially predisposing patients with insomnia to disordered breathing due to respiratory instability23.

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of COMISA among Asian patients with OSA utilizing consecutive sampling within a clinical population. We hypothesize that the prevalence of COMISA among Asian OSA patients is similar to that previously reported in Western countries. We also expect that the clinical manifestations, objective sleep architecture, and the low arousal threshold of Asian patients with COMISA would be different from those with OSA alone.

Methods

The study prospectively recruited consecutive patients with excessive daytime sleepiness, heavy snoring, parasomnia or other distressing sleep-related complaints who were referred for overnight PSG at the Taipei Medical University Hospital sleep center, Taipei, Taiwan from middle July 2022 to Nov 2022. The study protocol was approved by the Taipei Medical University-Joint Institutional Review Board (TMU-JIRB No.: N202206040), and the subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations by TMU-JIRB. Among 249 patients referred for PSG during the study period, patients younger than 20 years (n = 21), those not referred for diagnostic PSG (n = 13), those who did not complete PSG (n = 2), those who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for OSA with an AHI of less than 5 events per hour (n = 38), and those who did not consent to participate (n = 5) were excluded from the study. Ultimately, 170 patients (136 males and 34 females) diagnosed with OSA were included in the final analysis.

Sleep study

An overnight laboratory-based PSG was performed on all participants using the EMBLA® N7000 system (Natus Neurology Incorporated). Participants were not permitted to consume caffeinated drinks or alcohol and were instructed not to take medications for insomnia on the day of the PSG study. The PSG included eight electroencephalogram channels, an electrocardiogram, an electrooculogram, electromyograms of the submental and bilateral anterior tibialis muscles, position sensors to record body position and movements, and respiratory monitoring which included pulse oximetry, oral and nasal airflow measurements, and thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort assessments. All PSG studies were manually scored by two experienced certificated sleep technicians independently according to the 2020 American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) criteria24. To reduce the inter-scorer difference, once a disagreement occurred between the two technicians, the third sleep technician would be involved, and the scoring agreed by any two sleep technicians was used as the final result.

Besides AHI, the results of PSG study provide the following data with sleep structures including TST, time in bed (TIB), sleep onset latency (SOL), WASO, SE, number of awakenings, the percentage of different sleep stages (stage N1, stage N2, stage N3, and rapid eye movement (REM) stage), number of sleep-stage transitions, and nadir oxygen saturation (SpO2). An arousal is scored when there is an abrupt shift of EEG frequency lasting at leat 3 s, provided that it is preceded by at least 10 s of stable sleep. This scoring criterion is based on the foundation definition established by the American Sleep Disorders Association (ASDA) in 1992, with minor modifications. The arousal index (AI, number of micro-arousals per hour of sleep) and spontaneous, movement-related, and respiratory-related arousal events were also calculated.

The assessment of OSA

To assess the presence and severity of OSA, AHI was calculated as the total number of sleep apnea and hypopnea per hour of sleep24. Apnea was defined as the complete cessation of airflow for at least 10 s, while hypopnea was defined as a reduction of at least 30% in airflow from the pre-event baseline for a minimum of 10 s, association with either at drop of least 3% arterial oxygen desaturation or arousal.

The assessment of insomnia

To assess insomnia, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted by a board-certificated psychiatrist. The evaluation focused on whether the patients reported dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity, characterized by difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, or experiencing early morning awakening at least three days per week for more than one month. Although current diagnostic criteria define insomnia disorder as symptoms persisting for at least three months, previous studies have largely relied on interviews or questionnaires assessing sleep complaints over the past month. Therefore, in this study, we adopted a criterion of insomnia symptoms persisting for more than one month for comparison purposes. Self-reported questionnaires were also used as supporting evidence.

The assessment of the low arousal threshold endotype

The assessment of the low arousal threshold was conducted using clinical predictors developed by Edwards and colleagues25. One point was allocated to each of the subsequent three criteria: (1) an AHI of less than 30 events per hour; (2) a nadir SpO2 surpassing 82.5%; and (3) a hypopnea fraction of total respiratory events exceeding 58.3%. A score of 2 or more may indicate a low arousal threshold, which has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity previously (80.4% and 88.0%, respectively).

Self-reported questionnaires

All participants completed the following questionnaires on this night of sleep study. The Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) was used to assess overall sleep quality, while the Chinese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) evaluated daytime sleepiness26. The severity of depression and anxiety was assessed using the Chinese versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The validity of these questionnaires has been tested to ensure accurate assessment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (USA). Clinical manifestations and sleep structure parameters were compared between patients with COMISA and OSA alone. Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. The normality of the distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the independent t-test and the Chi-square test (Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test value). All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Among 170 patients recruited with a diagnosis of OSA, 68 individuals (40%) met the criteria for COMISA. The socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 49.1 years, with the COMISA group averaging 49.4 ± 13.6 years and the OSA group averaging 48.9 ± 13.4 years. There was no significant difference in age between patients with COMISA and OSA alone (p = 0.82). Gender distribution also did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.18) despite the study sample consisting mostly of males (80%). The BMI in COMISA patients (25.2 ± 3.8 kg/m2) was lower than in OSA patients (26.6 ± 4.8 kg/m2), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Additionally, no significant differences were found in education, marital status, or socioeconomic status between patients with COMISA and OSA alone.

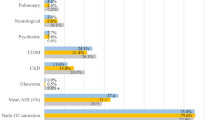

Medical comorbidities and results of self-reported questionnaires are detailed in Table 2. Overall, patients with COMISA were more likely to have comorbid medical conditions compared to those with OSA alone (p = 0.03). The prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and fatty liver was higher in patients with COMISA, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. There was no difference in the severity of daytime sleepiness, as indicated by the ESS scores, between the two groups (p = 0.21). However, patients with COMISA reported worse sleep quality and exhibited higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to those with OSA alone (The p-values for the PSQI, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 scores were all less than 0.001).

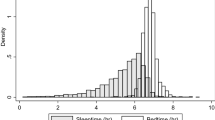

Although COMISA patients complained of worse sleep quality, all objective sleep architecture parameters derived from PSG showed no significant differences between patients with COMISA and OSA alone (Table 3). Arousal events and the clinical predictors for the low arousal threshold endotype are presented in Table 4. The total arousal events and the AI did not differ significantly between the two groups, but the number of spontaneous arousals was significantly higher in patients with COMISA (p = 0.03). In terms of the low arousal threshold endotype, the distribution was similar between patients with COMISA and those with OSA alone.

Discussion

In our study, 40% of patients with OSA also suffered from insomnia. This finding aligns with the earlier review by Luyster and colleagues, which reported that 39 to 58% of patients with OSA also had co-morbid insomnia27. Although previous studies have highlighted notable differences in the pathophysiology of OSA between Asian and Western populations28, our findings-despite employing more stringent criteria for diagnosing insomnia-demonstrate a similar high prevalence of COMISA.

While some studies suggest that elder and nonobese patients are more likely to have COMISA, our study found no significant differences in age, gender, BMI, or other sociodemographic variables between the two groups. These findings indicate that clinicians should routinely screen for insomnia symptoms among patients with OSA and should not rely solely on factors such as age, gender, and BMI, and vice versa.

Consistent with previous studies, patients with COMISA were more likely to have additional medical conditions compared to those with OSA alone8,11,14. However, the differences in individual medical conditions did not reach statistical significance. Given the cross-sectional study design and the predominance of middle-aged patients in the study cohort, it is possible that patients with COMISA may still experience adverse health outcomes during the follow-up period.

Moreover, in our study, COMISA patients were more anxious and depressed than those with OSA alone, reflecting the increased risk and severity of mood disturbances when both insomnia and OSA are present. This phenomenon is supported by a large population-based survey in the United States, where insomnia, OSA, and COMISA were all associated with depressive symptomology, with COMISA showing the highest odds ratio29. Although the study by Gupta and colleagues suggests that COMISA patients are not necessarily likely to be diagnosed with depressive or anxiety disorders, their reliance on a healthcare utilization database may have led to an underestimation of psychological consequences, potentially due to oversight by patients with sleep disturbances or their physicians13.

SOL and WASO were longer and SE was lower in patients with COMISA compared to those with OSA alone. Nonetheless, the differences in the sleep scoring data reported in standardized PSG did not reach statistical significance and the distribution of different sleep stages was also similar between the two groups, consistent with findings from previous studies14,15,17. Bianchi and colleagues proposed that the discrepancy between subjective perceptions of sleep and objective measurements of sleep, rather than variations in sleep architecture, may play a significant role in the development of insomnia19. These consistent findings suggest that objective sleep architecture parameters commonly used in routine practice may not effectively distinguish between COMISA and OSA, particularly among Asian patients.

Cortical arousal, which leads to sleep disruption, is recognized as a significant contributing factor to the adverse health consequences associated with both sleep apnea and insomnia. In our study, there were no significant differences in the total number of arousals or the arousal index between the two groups, although patients with COMISA exhibited more spontaneous arousals on the study night. In addition to arousal frequency, arousal intensity, indicated by heart rate fluctuations around arousal events, has been shown to have greater clinical relevance30,31,32. Consequently, further analysis baed on the concept of cardiac arousal may provide valuable insights into differentiating sleep archetecture between COMISA and OSA.

Furthermore, the distribution of the low arousal threshold endotype was similar between patients of COMISA and those with OSA alone in this study. Another study by Yanagimori and colleagues, using a type 3 home sleep apnea test, also failed to demonstrate different proportions of low arousal threshold between the two groups33. In an effort to improve the methodology, we utilized standardized PSG but still obtained similar results. However, some limitations may arise from the use of an algorithm instead of the standardized quantitative assessments typically performed in the physiological laboratory in both studies25. Recently, Brooker and colleagues successfully demonstrated that a low arousal threshold could be an overrepresented endotype in patients with COMISA by analyzing ventilatory flow patterns obtained from routine PSG signals22. Further studies are needed to definitively conclude whether a low arousal threshold is a characteristic feature of COMISA patients.

We acknowledge the recognizable limitations of the present study. First, it was conducted at a single sleep center using a cross-sectional study design, which may introduce sampling bias despite the use of consecutive sampling without selection. Second, while the determination of a low arousal threshold using an algorithm is feasible for clinical studies, potential misclassification may occur if the algorithm is not specifically developed for COMISA. Furthermore, although all patients were instructed to refrain from taking insomnia medications on the night of PSG study, residual effects may still have been present, potentially confounding the PSG measurements. Finally, the first-night effects of PSG could impact objective sleep architecture parameters; however, this effect would likely influence both groups equally and is therefore unlikely to affect the final results.

To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies focusing on COMISA in Asian populations. In conclusion, our study clearly demonstrates that COMISA is also commonly observed among Asian patients with OSA. Additionally, patients with COMISA are more likely to experience both adverse physical and psychological health outcomes. However, the results did not show significant differences in objective sleep architecture or the distribution of a low arousal threshold estimated by an algorithm. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of the low arousal threshold endotype in COMISA.

Data availability

The datasets generated in the current study are not publicly available due to their containing private information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sweetman, A., Lack, L. & Bastien, C. Co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA): prevalence, consequences, methodological considerations, and recent randomized controlled trials. Brain Sci. 12 (12), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9120371 (2019).

Gottlieb, D. J. & Punjabi, N. M. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: A review. JAMA 14 (14), 1389–1400 (2020).

Morin, C. M. & Buysse, D. J. Management of insomnia. N. Engl. J. Med. 18 (3), 247–258 (2024).

Guilleminault, C., Eldridge, F. L. & Dement, W. C. Insomnia with sleep apnea: a new syndrome. Science 31 (4102), 856–858. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.181.4102.856 (1973).

Krakow, B. et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest 120 (6), 1923–1929. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.120.6.1923 (2001).

Lichstein, K. L., Riedel, B. W., Lester, K. W. & Aguillard, R. N. Occult sleep apnea in a recruited sample of older adults with insomnia. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 67 (3), 405–410. (1999).

Sweetman, A. M. et al. Developing a successful treatment for co-morbid insomnia and sleep Apnoea. Sleep. Med. Rev. 33, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.04.004 (2017).

Draelants, L. et al. 10-Year risk for cardiovascular disease associated with COMISA (co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnea) in hypertensive subjects. Life (Basel) 13 (6), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13061379 (2023).

Cho, Y. W. et al. Comorbid insomnia with obstructive sleep apnea: clinical characteristics and risk factors. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 14 (3), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6988 (2018).

Lang, C. J. et al. Co-morbid OSA and insomnia increases depression prevalence and severity in men. Respirology 22 (7), 1407–1415. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13064 (2017).

Björnsdóttir, E. et al. Insomnia in untreated sleep apnea patients compared to controls. J. Sleep. Res. 21 (2), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00972.x (2012).

Krell, S. B. & Kapur, V. K. Insomnia complaints in patients evaluated for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 9 (3), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-005-0026-x (2005).

Gupta, M. A. & Knapp, K. Cardiovascular and psychiatric morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with insomnia (sleep apnea plus) versus obstructive sleep apnea without insomnia: a case-control study from a nationally representative US sample. PLoS ONE 9 (3), e90021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090021 (2014).

Lichstein, K. L., Justin Thomas, S., Woosley, J. A. & Geyer, J. D. Co-occurring insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 14 (9), 824–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2013.02.008 (2013).

Wulterkens, B. M. et al. Sleep structure in patients with COMISA compared to OSA and insomnia. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 19 (6), 1051–1059 (2023).

Chung, K. F. Insomnia subtypes and their relationships to daytime sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Respiration 72 (5), 460–465. https://doi.org/10.1159/000087668 (2005).

Yang, C. M., Liao, Y. S., Lin, C. M., Chou, S. L. & Wang, E. N. Psychological and behavioral factors in patients with comorbid obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia. J. Psychosom. Res. 70 (4), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.12.005 (2011).

Björnsdóttir, E. et al. The prevalence of depression among untreated obstructive sleep apnea patients using a standardized psychiatric interview. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 12 (1), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5406 (2016).

Bianchi, M. T., Williams, K. L., McKinney, S. & Ellenbogen, J. M. The subjective-objective mismatch in sleep perception among those with insomnia and sleep apnea. J. Sleep. Res. 22 (5), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12046 (2013).

Ma, Y., Goldstein, M. R., Davis, R. B. & Yeh, G. Y. Profile of subjective-objective sleep discrepancy in patients with insomnia and sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 1 (11), 2155–2163. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.9348 (2021).

Eckert, D. J., White, D. P., Jordan, A. S., Malhotra, A. & Wellman, A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 15 (8), 996–1004. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201303-0448OC (2013).

Brooker, E. J. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is a distinct physiological endotype in individuals with comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 20 (10), 1508–1515. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202304-350OC (2023).

Meira, E. et al. Comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea: mechanisms and implications of an underrecognized and misinterpreted sleep disorder. Sleep. Med. 84, 283–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.05.043 (2021).

Berry, R., Quan, S. & Abreu, A. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.6 (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2020).

Edwards, B. A. et al. Clinical predictors of the respiratory arousal threshold in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1 (11), 1293–1300. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201404-0718OC (2014).

Chen, N. H. et al. Validation of a Chinese version of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Qual. Life Res. 11 (8), 817–821. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020818417949 (2002).

Luyster, F. S., Buysse, D. J. & Strollo, P. J. Jr. Comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea: challenges for clinical practice and research. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 15 (2), 196–204 (2010).

Li, K. K., Kushida, C. A., Powell, N. B., Riley, R. W. & Guilleminault, C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a comparison between far-East Asian and white men. Laryngoscope 110 (10), 1689–1693. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200010000-00022 (2000).

Hayley, A. C. et al. The relationships between insomnia, sleep Apnoea and depression: findings from the American National health and nutrition examination survey, 2005–2008. Aust. N. Z.. J. Psychiatry 49 (2), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414546700 (2015).

Noda, A. et al. Effect of aging on cardiac and electroencephalographic arousal in sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 43 (9), 1070-1. (1995).

Noda A, Okada T, Katsumata K, Yasuma F, Nakashima N, Yokota M. Suppressed cardiac and electroencephalographic arousal on apnea/hypopnea termination in elderly patients with cerebral infarction. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 14 (1), 68–72. (1997).

Azarbarzin A, Ostrowski M, Hanly P, YounesSep M. Relationship between arousal intensity and heart rate response to arousal. Sleep 37 (4), 645–53. (2014)

Yanagimori, M. et al. Respiratory arousal threshold among patients with isolated sleep apnea and with comorbid insomnia (COMISA). Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 7638. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34002-4 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. contributed to conceptualization and methodology. T.H. contributed to data curation and formal analysis and wrote the main manuscript. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoc, T.V., Lee, HC. Clinical and polysomnographic characteristics of Asian patients with comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Sci Rep 15, 11529 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96825-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96825-7