Abstract

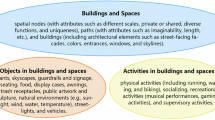

With the maturation and widespread adoption of digital technology, the integration of digital art into public spaces has emerged as a novel artistic design approach to enhance urban image. However, in the design and creation process, artists or designers often dominate, leading to a discrepancy between the artwork and the preferences or perceptions of the actual participants in public spaces, ultimately resulting in failure to achieve the desired outcomes. To design digital art installations in public spaces that attract user participation and interaction, it is essential to explore the mechanisms through which digital art influences public space design.To this end, the study first conducts a literature review to analyze the transformations under the mutual influences of digital art, public spaces, and users, thereby clarifying and defining the concepts and characteristics of digital art, public spaces, and users. Through this analysis, 15 design influence factors for digital art interventions in public spaces are identified, including scale, accessibility, and cultural-historical context. Subsequently, structural equation modeling (SEM) is employed to investigate the relationships and relative weights of the influences of public spaces, digital art, and users on users’ willingness to participate, as well as the correlations and weights among the 15 influencing factors, such as scale, accessibility, and cultural-historical context. The findings reveal that public spaces, digital art, and users all have positive effects on users’ willingness to participate. Furthermore, the 15 influencing factors, including scale, accessibility, and cultural-historical context, not only affect public spaces, digital art, and users but also directly influence users’ willingness to participate. This study uncovers the complex interactions among digital art, public spaces, and users, providing theoretical support for the design and implementation of digital art in public spaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Design oriented towards culture and art has become an important trend in the renewal of public spaces. With the widespread adoption and maturation of digital technologies, integrating digital art into public spaces has emerged as a novel method for enhancing urban imagery through artistic design. It was not until the late 1990s that digital art formally entered the realm of art. At that time, galleries and museums began to increasingly incorporate this art form into their exhibitions, dedicating entire exhibitions to showcasing digital artworks. However, most of these were still based on the “white cube” model. In public spaces, the environment of physical galleries/museums is no longer a symbol of identity. The intervention of digital art allows anyone to participate anytime and anywhere, without the need for museums to display or introduce the works to the public. After entering public spaces, digital art is no longer constrained by the physical boundaries of traditional public space artworks and can expand infinitely through virtual space, exhibiting a boundary—less characteristic1. This means that some participants are detached from the interpersonal connections within the physical public space, with weakened connections among participants and increased personal isolation. However, since individuals are active in different networks, a super—connection that transcends physical space is established. Overall, traditional public spaces have not been replaced but have been expanded and virtualized through the extension of their boundaries.

In this study, the term “public space” refers to the platforms or venues for the display of digital art. These carriers can be physical, such as paper, walls, physical spaces, or locations, or virtual, such as screens, mobile phones, computers, movies, or websites2. These constitute the basic medium for the creation of digital artworks. Although they all serve as fundamental platforms or media, the former are visible and tangible physical entities or spaces, while the latter are virtual spaces or venues based on screens, networks, or devices. This highlights the significant transformation of digital art in terms of spatial form. Digital art that intervenes in public spaces involves presenting digital artworks in public spaces and enabling real—time interaction with users. This art form emphasizes the mutual influence, communication, and participation between users and the artworks. After intervening in public spaces, digital art exhibits characteristics of publicity, variability, interactivity, and trans—mediality.

Firstly, digital art has the characteristic of publicity, meaning that this art form exists in public spaces and operates for the public good. Specifically, digital artworks can be presented and disseminated in public places and spaces, allowing more people to access and appreciate the art. Secondly, digital art emphasizes interactivity and participation. With the support of digital technology, users can interact with artworks in real—time and even manipulate and transform the works. This interactivity greatly enhances users’ sense of participation and immersion, making them part of the artistic creation process. Artists guide users to participate in the creative process by creating interactive digital artworks that offer personalized and enriched experiences. Thirdly, digital artworks exhibit significant variability. Because of their digital nature, the works can be easily modified, copied, and disseminated. Artists can adjust and refine their works at any time according to their needs, making their works more perfect. Lastly, digital artworks can transcend different media and integrate various art forms. The widespread application of digital technology enables digital art to cover and integrate numerous art forms such as painting, sculpture, music, drama, and film, creating new artistic experiences. The trans—mediality of digital art promotes communication and integration among different art forms and enriches its diversity and creativity. It can be seen that digital art in public spaces is no longer confined to traditional art forms. Through interaction and engagement, it incorporates users into the art, making them participants in creativity. This stimulates the integration of art and technology and brings greater possibilities for innovation and creativity. In this process, when digital art intervenes in public spaces, we need to explore not only the digital art itself but more importantly the participation of users. It is the organic coupling of digital art or technology, users, and public spaces that matters.

However, the design of digital art interventions in public spaces is typically dominated by artists or designers. This process can sometimes lead to inconsistencies between the artworks and the preferences or perceptions of the actual participants in the public space, resulting in outcomes that fail to meet expectations. How to design digital artworks for public spaces in a way that effectively attracts and engages users is an urgent issue today. The diversity and complexity of the environment, participants, and forms of digital art in public spaces lead to the complexity of factors influencing users’ willingness to participate. Meeting user needs is the core goal of design. However, user needs are diverse and constantly changing with market conditions and user demographics. Due to the diversity of user needs, designers often struggle to accurately identify the focus of the design. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the weights of design impacts in the early stages of the design process. By doing so, designers can better grasp the key elements, ensuring that the final product effectively addresses user problems and provides the desired functions and experiences3. In practice, when creating digital art for public spaces, designers often consider design impact factors based on personal experience. The weights of these elements usually come from the designers’ subjective judgments, which may lead to designs that do not align with users’ cognitive and behavioral habits, thereby reducing their willingness to participate4.

To address this issue, it is imperative to adopt a user - centered approach and utilize more objective and scientific methods to determine the weights of design impact factors. We have identified Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), also known as latent variable modeling or covariance structure analysis5. This method involves constructing a hypothetical causal model based on theoretical literature or empirical rules. Researchers then develop measurement scales for SEM based on the theoretical framework, collect relevant data through questionnaires, and analyze the data to verify the correctness and rationality of the hypothesized causal relationships. This process involves comparing the theoretical covariance structure with the actual sample covariance structure and attempting to minimize the discrepancy between them. SEM can directly observe measured variables, handle multiple dependent variables simultaneously, and account for measurement errors in the variables. Due to these characteristics, SEM has become an important data analysis tool in the design field, filling the gaps left by traditional statistical methods. After identifying the factors related to digital art interventions in public space design, SEM can be employed to analyze the impact weights of these factors on users’ willingness to participate, as well as to clarify the relationships between the factors. This will provide designers with necessary design priorities and directions. Consequently, designers can better understand user needs, grasp the key elements in the design process, and ensure that the product truly addresses user problems, providing the desired functions and experiences.

In summary, the study will focus on the weights of design impact factors for integrating digital art into public spaces. It will analyze relevant literature to identify key design impact factors and construct a survey questionnaire. Through questionnaire surveys and the application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), the study will explore the relationships and impact weights between public spaces, digital art, and users’ willingness to participate. Subsequently, discussions based on the results will reveal the underlying meanings of the data, providing valuable strategic recommendations for the future design of digital art in public spaces. The research process is illustrated in Fig. 1. These insights are particularly valuable for optimizing user experience and enhancing users’ willingness to engage with digital art in public spaces.

Overview of relevant theories

Digital art intervention in urban space

The terminology surrounding technological art forms has continuously evolved within academia. The art form commonly referred to today as “digital art” has undergone several transformations: it was initially known as “computer art,” followed by “multimedia art” and “cyber art” from the 1960s to the late 20th century, and more recently, “New Media Art.” This sequence of terminological changes reflects the ongoing evolution and development of the field. In the 21st century, “digital art” has become an umbrella term encompassing a wide range of artworks and practices, but it does not describe a unified set of aesthetics. A crucial distinction exists between art that uses digital technologies to create traditional artifacts, such as photographs, prints, or sculptures, and computable art that is created, stored, and disseminated through digital technologies, where the artwork’s identity is intrinsically linked to its digital medium. The latter is generally understood as digital art and is the focus of this study. These two broad categories differ significantly in terms of expression and aesthetics, existing within hybrid fields that are unique forms of creative expression.

Regarding digital art interventions in urban spaces, scholars both domestically and internationally have conducted extensive research. From an urban renewal perspective, Li Meixuan discusses the role of digital media technology in revitalizing key buildings in historic districts6. Additionally, Chen Xi explores the application of digital museums in displaying historical buildings in Beijing’s old city, detailing how digital museums can merge physical and virtual realities to enhance the presentation of these structures7. From the viewpoint of digital media technology, Chen Lin examines how digital art constructs interfaces for urban perception, illustrating through case studies how digital media can enhance the urban experience8,9,10. These studies highlight the capabilities of digital art in urban interaction, revealing its creativity and richness as an interface that shapes urban perception and contributes to understanding urban culture in the digital age. This body of research provides valuable insights into the role of digital media technology in architectural contexts, offering lessons on its application and value in exploring architectural developments.

Beyond digital art in public spaces, digital technology has also significantly impacted public art, prompting numerous studies. For instance, Yu Lingliang discusses how virtual spaces can enhance the “public nature” of public art and improve its accessibility1. Wang Feng examines the role of digital technology in promoting innovation in urban public art and interactive design11. Pengcheng Pan’s work on “Digital Participation: Public Art in Virtual Space” explores the influence of digital participation on public art12. Dong Yu and Ding Wenxia analyze the application of digital media technology in public art design and its impact on public art practices13. Zheng Jing’s research delves into the transition from “non-solid” to “non-material” in public art, examining the implications of immateriality on the field14. Liu Jianwei, Wang Weijia, and Chen Tong explore how digital information technology has transformed urban public art15. Cai Shunxing’s study on the “field” of digital public art provides an in-depth analysis of how digital art influences public art spaces16. These studies collectively explore the application and impact of digital technology in public art from various perspectives, covering topics such as virtual spaces, public art design, urban public art, immateriality, and digital public art. They employ a range of research methods, including theoretical analysis, empirical research, and case studies.

Internationally, research centers such as the Interactive Art Centre in Tokyo, Japan, and the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne, Germany, have become hubs for exploring the intersection of digital technology and art in public spaces. These centers bring together artists and technologists to infuse new vitality into art through digital innovations while conducting in-depth research on the application of digital art in urban environments. For example, Littwin investigates the connection between smart cities and digital art17. Borysova et al. examine the impact of the digital revolution on contemporary art, focusing on technological change, interactivity, and virtual aesthetics18. Charlie Gullström explores the role of presence design in the expansion of architecture19. Bidarra presents an interactive installation called “Feel Opo,” designed to enhance users’ understanding and perception of urban space.

In the realm of digital art applications, Wagner explores how to enhance social interactions in urban public spaces through playful elements, demonstrating that such elements can promote communication and interaction, thereby increasing the appeal of these spaces20. Kuangfan Chen investigates the categorization of playable digital interventions in urban public spaces21. Enrico Nardelli proposes a framework for categorizing interactive digital artworks based on the ways they engage with users22. These studies offer practical insights into the use of digital art, examining its methods and patterns of application in contemporary contexts.

The aforementioned studies provide extensive theoretical and practical analyses of various aspects of digital art interventions in public spaces, laying a foundation for understanding the role of digital art in these settings. However, it is noteworthy that the user experience level has received comparatively less attention in these studies.Through a review of the literature, we have identified several key factors influencing the integration of digital art into public space design:

-

(1)

Aesthetic of Art: From a research perspective, the concept of aesthetic in digital art can be elucidated through three aspects: communication elements, modes of expression, and principles of artistic design. In terms of communication elements, digital art utilizes digital media as the medium, leveraging basic elements such as pixels, resolution, color, and shape to convey the artist’s creative intent23. These elements interact to construct a rich visual sense of depth and three-dimensionality, thereby endowing digital artworks with unique aesthetic value. Regarding modes of expression, digital art represents both a continuation and innovation of traditional artistic techniques such as painting, sculpture, and photography24. From the standpoint of artistic design principles, digital art adheres to traditional principles including contrast and harmony, symmetry and balance, rhythm and movement25.

-

(2)

Functional Elements: Functional elements in digital art refer to the various roles that digital art can play. Practical functionality, cognitive functionality, and aesthetic functionality hold significant positions in digital art. Digital art’s practical functionality is manifested in its wide application across various fields26. The cognitive functionality of digital art is primarily reflected in its impact on users’ cognition and thought processes27. Digital artworks can convey information, ideas, and emotions to users in visual and auditory forms. The aesthetic functionality of digital art is demonstrated by digital artists’ ability to create unique and aesthetically pleasing works using a variety of digital tools28. Digital artworks can express the artists’ feelings and thoughts through elements such as color, form, and lines, evoking emotional resonance from users.

-

(3)

Economic Elements: When creating digital art, creators need to analyze and evaluate factors such as market demand, target users, and competitive landscape, including resource allocation for creation, cost estimation, and potential profit analysis29. In the process of digital art creation, creators use digital tools and platforms to engage in real creation. At this stage, economic elements mainly include the investment in creation tools, skill training, and learning costs. Additionally, the creation process of digital artworks may bring about collaborative effects, such as cooperation, crowdfunding, and sponsorship30. These collaborative processes are beneficial for reducing production costs, enhancing the quality of the works, and expanding market influence.

-

(4)

Digital Technology: The perspective of digital technology is mainly discussed from three aspects: technological integration and innovation, technological elements, and technological aesthetics. Technological integration and innovation endow artworks with more technological content, enhancing user resonance31. Technological elements are an important part of digital art. Production technology determines whether an artwork can be created, product technology determines the presentation form and quality of the artwork, and operational technology determines whether the artwork can be effectively controlled and utilized32. From the perspective of technological aesthetics, digital art fully embodies technological aesthetics, which is mainly manifested in the application of technological elements and the interpretation of technological concepts in artworks8,9,10.

-

(5)

Time: The concept of time in digital art refers to the temporal dimension involved in the creation and interaction of digital artworks. From a research perspective, it includes three aspects: interaction response time, interaction duration, and the temporal aspect of the artwork itself. Interaction response time refers to the speed at which a digital artwork responds to user input during the interaction process33. This is often a key element in digital art, as user experience is a crucial aspect of digital art. Interaction duration refers to the length of time that users interact with digital artworks34. This duration directly affects user experience and the presentation form of the artwork. The temporal aspect of the artwork refers to the time concept inherent in the digital artwork itself, including the time expressed by the artwork and the relationship between time and space.

User perspective

The user perspective is a user-centered approach that involves constructing usage scenarios and providing solutions by gaining a deep understanding of users’ needs and expectations. In this study, “users” primarily refer to individuals involved in the interaction with digital art in public spaces, including participants, creators, and viewers. Participants are those who actively engage with and interact with digital artworks. Creators are the individuals who produce these digital artworks, typically artists or designers. Viewers are those who observe the digital art without directly interacting with it. Despite their distinctions, these roles often overlap and transform into one another in various contexts. The participation of these individuals is crucial for the representation and experience of digital art in public spaces.

A well-designed system should exhibit behaviors and attributes tailored to specific conditions, making it both user-friendly and enjoyable for its target audience. Hongwei Zhu emphasizes the significant role of the user in product-service systems35. From a user perspective, sustainable design principles and methods are proposed, such as constraining interactions, providing feedback to users, and fostering environmentally friendly awareness. These principles aim to promote positive interactions between products and people, and to design solutions that are sustainable, human-centered, and effective.

Domestic scholars have increasingly focused on the user perspective, initiating research across various fields from the user’s point of view. For instance, evaluating archived websites with a user-centric approach has led to suggested improvements. Deng Jun found that user perception offers a comprehensive measure of website quality when assessing the service quality of archival websites36. Shen Hongzhou and colleagues developed an index system for assessing the quality of crowdsourcing websites from the customer’s perspective, continuously refining it to obtain the latest insights37. Yao Yao constructed an evaluation index system from the customer’s perspective, conducting surveys and data analyses on group-buying websites, and ultimately developed a reasonable evaluation framework38. Compared to foreign research, the exploration of the user perspective in domestic studies began relatively late, often drawing on international findings. Initially, research in digital art interventions in public spaces was more aligned with the creators’ experiences, focusing on self-expression by artists or government-led initiatives. However, as the user perspective has gained prominence, it has become clear that the novelty and engagement of digital artworks may not always resonate with users. This underscores the need for deeper understanding of user needs and closer alignment with real user demands.

International research on user perspectives began earlier, with different disciplines gradually recognizing the importance of users. In the context of website evaluation, foreign scholars have also emphasized user participation. For example, Tsiaousis and Giaglis focus on user experience in mobile website design, proposing a usability evaluation method that highlights the importance of user experience39. Carta et al. introduced a tool for remote user experience evaluation called Web Usability Probe, designed to help website designers understand and improve user needs and experiences by collecting feedback40. These studies emphasize the critical role of user feedback in website design, asserting that user experience is a key factor in a website’s success. They also highlight the importance of considering different device types, such as mobile users, to ensure that website design is both effective and engaging41.

The research from a user perspective has demonstrated the feasibility of theoretical analysis and practical application of user - centered design methods. Furthermore, the user - level factors can be categorized into the following aspects:

-

(1)

Psychological Expectations: Psychological expectations of users refer to the psychological experiences pursued based on different motivations when utilizing public spaces, mainly manifested in four aspects: celebration and gathering, leisure and entertainment, venting and release, and identity recognition. Celebration and gathering provide opportunities for the public to celebrate together, fulfilling social, cultural, and emotional needs, and enhancing social solidarity and a sense of identity42. Leisure and entertainment, as an important function of public spaces, offer recreational activities through parks, amusement venues, and performance halls, thereby improving the quality of life. Venting and release refer to the process where people relieve stress and alleviate tension through physical activities and expressions in public spaces, such as outdoor sports facilities43. Identity recognition is fostered through collective activities, social interactions, and shared experiences, enabling users to develop a sense of belonging and identity with public spaces, and promoting social connections and cultural exchanges44.

-

(2)

Visual Experience: Visual experience of users refers to the psychological experiences gained during the process of perceiving and interacting with visual images, which can be understood from five aspects: perceptual identification experience, emotional response experience, image interpretation experience, visual memory experience, and visual cultural experience. Perceptual identification experience involves recognizing the attributes of images such as color, shape, and texture through visual perception45. Emotional response experience refers to the emotional reactions triggered by images, such as preferences, aversions, excitement, or calmness. Image interpretation experience is the process of interpreting the subject, meaning, and symbols of images based on personal experiences, cultural background, and knowledge. Visual memory experience involves recalling and reproducing images, forming visual memories. Visual cultural experience is related to the cultural connotations carried by images, reflecting their significance within a cultural context. These experiences collectively constitute the comprehensive psychological experience of users with images46.

-

(3)

Aesthetic Ability: Aesthetic ability of users refers to an individual’s knowledge, skills, experience, and understanding of aesthetic values in the field of aesthetics. It is mainly reflected in three aspects: aesthetic judgment, aesthetic orientation, and aesthetic expression. Aesthetic judgment is the ability of users to evaluate the aesthetic value, style, and meaning of artworks, cultural products, or design works, which is the foundation for accurately recognizing aesthetic value and creating unique aesthetic experiences47. Aesthetic orientation represents the personalized preferences of users for beauty, which vary due to differences in aesthetic experiences, cultural backgrounds, and living environments, leading to diverse evaluations of the same work48. Aesthetic expression involves sharing aesthetic experiences and emotions with others through various means such as language, painting, music, and dance, thereby evoking resonance and communication.

-

(4)

Interpretation of Artworks: The interpretation of artworks by users refers to the process of cognition and interpretation of artworks by individuals, which can be academically described from three aspects: the concept of the work, the evaluation of its meaning, and its social value49. The interpretation of the concept of the work involves recognizing its inherent ideas (positive or negative humanistic connotations), emphasizing a unified way of understanding the subject and object. The evaluation of the work’s meaning involves judging the significance conveyed by the artwork. The social significance of digital artworks is regarded as a form of social utility evaluation, and its public opinion orientation directly affects public perception. The interpretation of the social value of the work focuses on its value at different levels, including value to others, collective value, self—value, social value, and existential value, such as the work’s role in personal self—discovery, expression, and the inspiration and resonance it brings to others.

-

(5)

Multi—Sensory Experience: Multi—sensory experience is an important way to enhance user experience, involving the combined effect of multiple senses such as vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell50. In terms of visual experience, elements such as clear interface composition, high—resolution images, reasonable color matching, and smooth animation playback can enhance visual appeal and interaction willingness. Auditory experience is enhanced through clear sounds, standard music, and appropriate sound effects, increasing user affinity and immersion. Tactile experience focuses on the touch feel of the interface and button feedback, affecting user satisfaction with the product. Although taste and smell experiences are not widely applied in public spaces, they provide unique immersive experiences in specific scenarios (such as digital art related to food and drink, or fragrance e—commerce) through aromatic and taste—related elements.

Public space

In this study, the term “public space” refers to a platform or medium for displaying digital art. This can be physical, such as paper, walls, or physical locations, or virtual, such as screens, mobile phones, computers, films, or websites. These serve as the fundamental media for the creation and presentation of digital artworks. While both physical and virtual spaces function as basic platforms, the former is a tangible, visible entity or space, whereas the latter exists in the digital realm, relying on screens, networks, or devices.

The complexity of public space, its multidisciplinary nature, and its deep roots in urban history have long attracted scholarly attention. Researchers have explored various aspects such as vitality, systems, qualities, forms, and squares41. However, the study of public space as a core topic in urban research is still relatively nascent, particularly since the 1960s when Europe’s economic crisis led to a social crisis that prompted a critical rethinking of modernist urban planning, which had been dominated by functional zoning. In response to the evolving meanings of public space, Western scholars have developed a range of theoretical frameworks, with the field’s development broadly divided into four stages: the formation stage, the development stage, the refinement stage, and the data era.

The formation stage occurred around the 1950s, primarily within socio-philosophical-political discourse. Following the “Second Industrial Revolution,” Western societies experienced a rise in self-awareness, leading to increased public participation and civic engagement. In 1958, Hannah Arendt introduced the concept of the “public sphere,” while Habermas defined it as the space and time between the private interests of civil society and the sphere of state power51. Subsequently, Lewis Mumford formally incorporated the concept of public space into urban studies52.

The development stage, spanning the 1960s and 1970s, focused on the humanistic dimension of public space. Influential scholars emerged during this period. For instance, Scaringe advocated for urban perception as a means to create uniquely attractive urban images (Scaringe, 2001). Manfredin emphasized designing comfortable public spaces, particularly highlighting the importance of streets and squares (Clive Munfordin, 2004). Oscar Newman introduced the concept of defensible space, emphasizing the relationship between urban design, community stability, and quality of life53. Christopher Alexander proposed a human-centered approach to urban design, analyzing the impact of the urban environment on human behavior and emotions54. Similarly, Jan Gehl, a strong advocate of human-centered design, made significant contributions to the development of public spaces in Copenhagen55. Jane Jacobs critically examined urban development issues and challenged conventional urban planning approaches56.

The refinement stage, occurring in the 1970s and 1980s, brought a broader and more diversified understanding of public space. During this period, public space gained widespread recognition. William H. Whyte explored the sociological importance of public space in small cities, arguing that it serves as a vital area for socialization, communication, and interaction, which significantly impacts urban community development and quality of life. He emphasized that public space design should be people-centered, focusing on human needs and behavior patterns 57. Ashihara Yoshinobu, by observing and describing streets, proposed a theory that highlights the quality and experience of street spaces, arguing that streets are not merely transportation routes but crucial places for social interactions58. He emphasized the impact of elements such as scale, openness, and landscape on street experiences. Norberg-Schultz explored the concept of the "spirit of place," underscoring the importance of place in shaping human emotions and memories and the role of architecture in reflecting these characteristics59. These scholars collectively stressed the interactive relationship between urban spaces and people, advocating for a human-centered approach in the design and planning of public spaces, with a focus on perceptions, experiences, and needs.

The data era, from the 1980s to the present, has been characterized by multidisciplinary theoretical integration and the advancement of spatial quantitative research. The rise of the digital age has led scholars to incorporate multidisciplinary theories in their quantitative studies of public spaces, moving beyond perceptual analyses to delve into issues such as morphological features, vitality indicators, comfort, and the interpretation of openness and publicness. For example, Pryke reviewed the spatial redevelopment of the City of London, providing an in-depth analysis of how spatial matrix changes contribute to urban development (60. Hillier and Hanson applied a sociological approach to study human behavior and interactions within urban spaces61.

In terms of research methodology for public spaces, tools such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), traditional social surveys, and quantitative statistical analyses have been widely employed62. For instance, Bishop et al. used virtual environments to assess countryside walking path choices, analyzing human behavior and the factors influencing these choices63. Heeyeun analyzed the distribution of private public spaces in Manhattan, mapping their use and the development of public activities through fieldwork and data collection, and discussing the spatial analysis results in conjunction with empirical observations (Heeyeun Y, Sumeeta S, 2015). Nemeth and Schmidt conducted empirical research on the use of public space after privatization and its impact on urban residents’ activities and interactions64. Smith, through case studies, examined the phenomenon of public space privatization and its impact, discussing the creation of public spaces and the evolution of urban spatial structures, and analyzing how privatization affects urban residents’ lives65.

The research on public spaces integrates empirical studies, mathematical modeling, and spatial analysis, proposing corresponding recommendations and strategies. These studies provide significant theoretical support and practical references for the research methods of digital art interventions in public spaces. Through a review, we have identified several key factors at the public space level:

-

(1)

Scale: The scale of public spaces refers to the impact of spatial size on human perception and utilization, which can be described from three aspects: planar scale, vertical scale, and visual scale66. Planar scale refers to the ground area, where smaller spaces can make people feel crowded and uneasy, while larger spaces provide a sense of spaciousness and freedom, such as the contrast between a large lawn in a park and a small square. Vertical scale refers to the three—dimensional dimensions of space (height, width, depth), where smaller spaces can be oppressive and constraining, while larger spaces offer freedom and comfort, such as the difference between a high—ceilinged shopping mall and a low—ceilinged corridor. Visual scale refers to the range of scenery visible within the space, where a good view can make people feel comfortable and relaxed, while a narrow view can be oppressive and tiring, such as the contrast between an open city square and a blocked—off line of sight67. The scale of public spaces significantly affects human cognition and utilization. During design, it is necessary to plan the spatial size and form reasonably according to human needs to create a comfortable and pleasant environment.

-

(2)

Accessibility: The accessibility of public spaces refers to the ability of people to conveniently enter and use these spaces68, which is mainly measured from three aspects: spatial connectivity, foot traffic, and population density. Spatial connectivity is an important indicator of accessibility and can be measured by the degree of road network development, the convenience of public transportation, and walking distance69. Public spaces with well—developed roads, convenient transportation, and short walking distances have stronger accessibility. Foot traffic is also a key measure of accessibility. Public spaces with high foot traffic indicate strong attractiveness and good accessibility, which can be obtained through surveys and statistics. Population density is equally important. Public spaces in densely populated areas are more likely to be used and have better accessibility. Only with good spatial connectivity, high foot traffic, and population density can public spaces better serve urban residents70.

-

(3)

Cultural and Historical Context: The cultural and historical context of public spaces is mainly studied from three aspects: cultural environment, temporal influence, and natural scenery. In terms of cultural environment, public spaces are the main venues for displaying traditional customs,Local flavor, and architectural styles, reflecting the unique culture of a place71. From the perspective of temporal influence, public spaces not only record the trajectory of cultural evolution but are also deeply affected by factors such as wars, social unrest, and celebrity culture72. In terms of natural scenery, public spaces interact with the surrounding natural environment, and natural landscapes become an important part of them, providing spaces for people to enjoy, relax, and entertain73. Studying the cultural and historical context of public spaces can reveal their diverse cultures and historical connotations, promote the inheritance of historical culture, and provide references for urban planning and design to better protect and utilize their historical and cultural value.

-

(4)

Management and Operation: The management and operation of public spaces cover four aspects: government policies, management regulations, operational services, and social willingness. Government policies guide the development and management of public spaces through regulations, involving urban planning, land use, economy, and environmental protection. Management regulations clarify the norms and responsibilities for space use, covering order maintenance, environmental cleanliness, and public safety. Operational services include facility maintenance, cleaning, safety management, and the organization of public activities, aiming to enhance the comfort and attractiveness of the space and promote community development. In terms of social willingness, encouraging citizen participation and feedback can enhance community cohesion and improve space utilization and satisfaction74.

-

(5)

Climate Conditions: The climate conditions of public spaces have an important impact on their use and comfort, mainly involving four aspects: wind, humidity, temperature, and precipitation75. The strength and direction of the wind directly affect people’s feelings. Strong winds can make people feel cold and uneasy, while moderate winds can bring a cool and pleasant atmosphere. Humidity affects people’s comfort. High humidity makes the air sticky and affects heat dissipation, while appropriate humidity enhances comfort. Temperature is a key factor in the utilization of public spaces. High or low temperatures can make people uncomfortable and reduce space usability, while suitable temperatures encourage people to participate in activities and leisure. The frequency and intensity of precipitation also affect the use of public spaces. Excessive precipitation can make spaces slippery and unfavorable for activities, while less precipitation is conducive to outdoor activities. These climate elements directly relate to the comfort and usage experience of public spaces. Through scientific understanding and optimized design, the planning and management of public spaces can be enhanced to provide better usage experiences for people.

User participation intention

User Participation Intention" is a key concept that describes the intrinsic tendency and subjective willingness of individuals to participate in specific activities or systems76. This concept is particularly important in studies related to user experience (UX), product design, and virtual communities. User participation intention not only reflects the positive attitude of individuals towards participation but also involves their expectations of benefits, perceived ease of use, and social impact of the participation behavior. Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes the influence of individual self—efficacy and outcome expectations on participation intention77. When users believe they can successfully complete a task and anticipate positive outcomes from it, their participation intention significantly increases. User participation intention is a multidimensional construct that can comprehensively reflect the psychological and behavioral characteristics of users in design activities. In empirical research, this variable is usually measured through scales and analyzed in conjunction with methods such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to reveal its relationships with other design variables (such as user satisfaction and design quality). In the field of design, understanding and enhancing user participation intention is of great significance for optimizing user experience, promoting product innovation, and enhancing user loyalty.

Research methods

Research idea

This study was conducted in the form of a questionnaire. The study was conducted in the form of a questionnaire survey. No human experimentation was involved in the research process. The human participation was limited to social surveys, and all participants were volunteers. Data collection was conducted anonymously. In addition, we confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and all experimental protocols have been approved by the author’s affiliated institution. In addition, in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study, and the anonymity and confidentiality of participants were ensured. Participation was entirely voluntary. Moreover, in February 2023, the National Health Commission, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Science and Technology, and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China jointly released the Regulations on Biomedical Research Involving Humans. Article 32 of these regulations stipulates that certain types of biomedical research involving humans may be exempt from ethical review if they involve the use of human information or biological samples without causing harm to individuals, do not involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests, and meet other specified conditions. Our study falls under the second category mentioned, which involves the use of anonymized information for research purposes. Therefore, our study does not involve any ethical violations. The first part of the questionnaire is to investigate the basic demographic information of the respondents45. The second part of the questionnaire primarily focuses on the influencing factors addressed in 2. the overview of relevant theories: public space, users and digital art, with 15 secondary indicators. Digital art is represented by five dimensions: artistic aesthetics, functional, economic, technology, and time.Users are represented in five dimensions: psychological expectations, image experience, aesthetic ability, work interpretation, and multi-sensory experience.Public space is characterised by five aspects: scale, accessibility, human history, management and operation, and climatic conditions.The questionnaire was set up using the Lietke 7-point scale.

Research hypothesis

User participation willingness refers to the degree of user involvement and interest in a product or service. In the design process, it is important to understand the elements and influences of users‘ willingness to participate, so as to help designers better understand users’ needs and expectations.

Combining the elements of influence of digital art intervention in public space, the study makes the following hypotheses:

-

H1:

Public space positively influences users’ willingness to participate.

-

H2:

Scale, accessibility, human history, management and operation, and climatic conditions affect public space.

-

H3:

Users themselves influence their participation experience.

-

H4:

Users themselves are influenced by psychological expectations, interpretation of the work, experience with images, aesthetic ability and multisensory experience.

-

H5:

Digital artworks positively influence users’ willingness to participate.

-

H6:

Artistic aesthetics, functional elements, economic elements, digital technology and time influence digital artworks.

Questionnaire survey

The study focuses on digital art projects that have been implemented and those that are planned for implementation, including public spaces, digital art or public art exhibitions, as well as relevant academic conferences. Therefore, the main survey includes artists and designers involved in the landing of digital art; users involved in digital artworks and experts and scholars related to the research direction. Especially in terms of users, the author conducted interviews and exchanges with users living in different city grades and different age groups by visiting the cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Wuhan and Wuxi.

The study employed a random sampling method for data collection. The survey process was designed to encourage active participation, and respondents were given a representative souvenir as a reward. The questionnaire survey started on 15 July 2023 and ended on 30 September 2023. The survey team distributed 330 questionnaires and collected 305 valid questionnaires. The questionnaire comprises 16 latent variables, including 15 independent variables and 1 dependent variable (participation willingness). Each latent variable is measured by a different number of observable variables, as detailed in Table 1. A Likert 7-point scale was used for measurement (1 = “Strongly Disagree,” 7 = “Strongly Agree”). After survey completion, items were aggregated into corresponding datasets for analysis. The effective sample size was 305. According to the study by Bentler and Chou78, the ratio of sample size to free parameters should be at least 10:1. Additionally, Jackson79 recommended through Monte Carlo simulation studies that the sample size should be at least 200. Therefore, the use of a sample size of 305 in this study is justified.

Table 1.

Findings of the study

Descriptive statistical analysis

Table 2 shows that the number of male and female respondents tends to be the same, with slightly more males. At the age level, the 18–44 age group dominates and accounts for the highest proportion, while the number of people in the 12–17 and 45–59 age groups tends to be similar, but the 45–59 age group is overrepresented, and people over 60 also account for an important proportion. At the level of city of residence, the first-tier population is the largest, followed by second- and third-tier cities.

Sample reliability and validity analysis

For the data collected using the scale, firstly, its reliability and validity (including convergent validity, discriminant validity, structural validity) need to be tested, i.e., the reliability and validity of the measurement model in the hypothetical model should be tested according to the collected data; secondly, if the reliability and validity are qualified, the data should be subjected to the test of common method bias and the analysis of the correlation between the variables, and then construct the structural model for Subsequent testing80. The software used in this study included SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) version 26.0 and AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures) version 27.0. The URL for these software products is https://www.ibm.com/spss.The data in this study contained both first order latent variables and second order latent variables and therefore needed to be stratified to test their reliability and validity.

Reliability analysis of first-order latent variables

Reliability analysis of first-order latent variables

Reliability analyses test the stability and consistency of the data in the scale. The reliability of the measurement model was calculated using Cronbach’s α coefficient in SPSS 26.0 software. Generally speaking, in basic research, when the Cronbach’s α coefficient value of each variable is greater than 0.7, it indicates that the survey data have good reliability. After the test, the overall reliability of the survey data is 0.976, and the Cronbach’s α value of each latent variable is above 0.7, which indicates that the reliability of the first-order latent variable research data is high, and it can be used for the next analysis.

Validity analysis of first-order latent variables

Validity generally refers to the degree to which a measurement scale can correctly measure the trait being measured, i.e., characterising the deviation between the data measured by the scale and the true value, including convergent validity, discriminant validity and structural validity. Using SPSS26.0 to test the survey data, the KMO value is 0.987, and the approximate chi-square value of Bartlett’s test of sphericity is 6590.745 and the result is significant, so it can be seen that the survey data have good validity as a whole.

Structural validity analysis

For the constructed hypothetical model of validated factor analysis, the structural validity should be tested first, to check whether the model is fitted or not, and if it cannot be fitted, the path and correlation should be re-assumed. The model fit test should simultaneously consider the absolute fit, value-added fit, and parsimony fit in several aspects of the fit index. The cardinal degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) of 1–3 indicates that the model fit is acceptable; the square root of the asymptotic residual sum of squares (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)) < 0.05 indicates that the model fit is acceptable; the three fit indicators of value-added fit, the Modified Fit Index ( Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Fit Index (TLI) of value-added fit are all > 0.9, indicating a good model fit; Parsimony Fit Index (Parsimony) is a good model fit; Parsimony Fit Index (PFI) is a good model fit; Parsimony Square Error of Approximation (PSEA) is a good model fit; Parsimony Square Error of Approximation (PSEA) is an acceptable model fit. Parsimony Goodness of Fit Index (PGFI), Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) are > 0. 5, indicating a better model fit. The test results are shown in Table 3, the main fitting indexes are all within the standard value range, indicating that the model fit is good.

Analysis of convergent validity

Most studies have used combined reliability (CR) and mean variance extraction to measure the convergent validity of the model. The results of the convergent validity test of each latent variable are shown in Table 4, the factor loading values of the topics corresponding to each latent variable are all greater than 0.7, indicating that the topics corresponding to each latent variable are representative, and at the same time, the AVE values of the mean variance coefficient of variation (AVE) of the latent variables are all greater than 0.5, and the CR of the combination is all greater than 0.8, which indicates that the effect of convergence is more satisfactory and has a better internal consistency.

For the purpose of data analysis, the study defined Human History as HH, Management and Operation as MO, Climatic Conditions as CC, Psychological Expectations as PE, Image Experience as IE, Aesthetic Ability defined as AA, Work Interpretation defined as WI, Multisensory Experience defined as ME, Willingness to Participate defined as WP, Public space defined as PC, Digital Art is defined as DA.

Discriminant validity analysis

The survey data should also be tested for discriminant validity after having good reliability and convergent validity to prove that there is a link between the variables and good internal consistency along with differentiation. Generally, the discriminant validity of a model is measured by comparing the correlation coefficients between the AVE values of the variables after square rooting them. If all the values of AVE after square rooting are greater than the correlation coefficients between the variables, it means that the data have good discriminant validity. After the test, from the results of Table 5, it can be seen that the AVE open square root values of each latent variable are greater than the correlation coefficients between the variables, which indicates that there is a certain degree of variability between the latent variables, and that the survey data have good discriminant validity.

Reliability analysis of second-order latent variables

Adopting the same method described above, the hypothesis model of validated factor analysis of second-order latent variables was constructed. After that, the reliability and validity tests were carried out in turn, and the results are shown in Tables 6, 7, 8 and 9. According to the test results, it can be seen that the reliability of the survey data of the second-order latent variables is good, and the reliability is high. At this point, all the data obtained from this research have been tested, and according to each test criterion, it can be seen that the data reliability and validity test passed, and can be analysed in the next step.

Tests for common method bias

Common method bias is an artificial covariation between predictor and target variables due to the same data sources or raters, the same measurement environment, the context of the item, and the characteristics of the item itself.On the basis of procedural controls such as anonymous completion, the common method bias was examined by ‘controlling for unmeasured single-method latent factors’, i.e., adding the common method factors for validation factor analysis, as shown in Table 10. The new model was constructed by adding the latent variables containing all the method factors to the validity analysis model described above, and the fit indices of the two models before and after the addition of the common method factors were compared: △X2/ df = 0.047, △CFI = 0. 007, △IFI = 0. 007, △TLI = 0. 006, △RMSEA = 0.002, △SRMR = 0.0184. 0.0184. It can be seen that there is no significant improvement in the model after the addition of the common method factor, and the changes in RMSEA and SRMR do not exceed 0.05, and the changes in CFI and TLI do not exceed 0.1, which proves that there is no serious common method bias.

Analysis of factors influencing willingness to participate

As can be seen from Table 11, it is assumed that all the paths in the model all positively and significantly affect the dependent variable willingness to participate, i.e., the P-value of the influence of public space, digital art, and user on willingness to participate is less than 0.05 (in AMOS, when the P-value is less than 0.001, it is shown as ***). In addition to this, the second-order latent variables under each of the three first-order latent variables of venue, digital art, and user have a positive and significant influence, and the degree of influence can be analysed based on their regression coefficients.

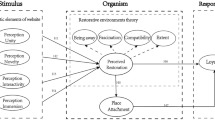

The results of the study show that there is a positive relationship between public space, digital art and users on users’ willingness to participate. In the above analyses, a potential mediating relationship has been formed between the first-order latent variables, the second-order latent variables, and the dependent variable participation willingness, as shown in Fig. 2. For example, the variable scale indirectly affects the willingness to participate through the variable.

In the data analysis stage, the combination of the qualifying ranges of each indicator indicates that the hypothesis of the influence relationship of each indicator is valid and that there is a strong explanatory power of each indicator. In the structural model, the influence of public space, users and digital art on the willingness to participate is in the following order: 0.557, 0.224 and 0.253. It shows that public space has the strongest influence on users’ participation in digital art in public space, and that the influence of users and digital art on the willingness to participate is weaker but more balanced. among the three extrinsic latent variables constituting the model, the variable of public space is composed of five indicators: scale, Accessibility, human history, management and operation, and climatic conditions, and the factor relationship between the indicators and the latent variables is 0.303, 0.211, 0.163, 0.128, and 0.120, indicating that the influence of public space on the digital art intervention in public space is more in the aspect of scale, but the explanatory power of accessibility and human history is not weak, and the influence of management and operation and climatic conditions is weaker. The user variable also consists of five indicators: psychological expectation, interpretation of works, multi-sensory experience image experience, aesthetic ability and multi-sensory experience, and the factor relationships between the indicators and the latent variables are, in order, 0.130, 0.247, 0.166, 0.179, and 0.248. It indicates that the influence of users on digital art interventions in public space is more reflected in the multi-sensory experience of individual users, and the influence of psychological expectations are relatively weak. The variables of digital art itself are composed of artistic aesthetics, functional elements, economic elements, digital technology and time. The factor relationships between the indicators and the latent variables are 0.203, 0.152, 0.557, 0.149 and 0.134, indicating that the influence of digital art itself on interventions in public space is more in the economic aspect, followed by the artistic aesthetic aspect. The three influences of function, digital technology and time are weaker, but the indicators are very close to each other, implying that the three indicators have a more balanced influence on digital art interventions in public space.

Tests for mediating effects

In the model constructed above, a potential mediating relationship has been formed between the first-order latent variables, the second-order latent variables, and the dependent variable willingness to participate, such as the variable scale indirectly affecting willingness to participate through the variable. While the correlation analysis between variables in the above model can only obtain the trend of covariance, how the variables interact with each other, whether the second-order latent variables can directly affect the willingness to participate and to what extent need to be tested by the mediation model. Therefore, the mediation model was constructed by combining all the second-order latent variables and the affiliated first-order latent variables with the dependent variable, willingness to participate. Model4 in the SPSS macro program PROCESS was used for the analysis, and the bias-corrected non-parametric percentile Bootstrap (repeated sampling 5000 times) was used for the mediation test.

Combined with the results of the mediated effects analysis, this is shown in Fig. 3. The direct effects of scale, accessibility, human history, management and operation, climatic conditions, psychological expectations, work interpretation, multisensory experience, image experience, aesthetic ability, artistic aesthetics, functional elements, economic elements, digital technology, and time on the willingness to participate were, in order, 0.308, 0.258, 0.202, 0.303, 0.225, 0.251, 0.209, 0.264, 0.218, 0.357, 0.278, 0.228, 0.204, 0.213, and 0.186. suggesting that aesthetic competence has the highest direct effect on willingness to participate, followed by scale aspects. The direct effects of accessibility, psychological expectations and multisensory experience were more balanced.

Discussion

Analysis of influencing elements of digital Art

The influence of digital art and users on the willingness to participate is relatively balanced; however, the influence of digital art is slightly higher. Based on the results, the following conclusions can be drawn: Hypotheses H3 and H5 are supported. Among the elements influencing digital art, economic factors are the most significant, followed by artistic aesthetics. Functionality, digital technology, and time have a lesser impact. These elements also mediate users’ willingness to participate, with artistic aesthetics having the greatest total effect, followed by functionality and economic factors. Digital technology and time had a smaller impact. These results also confirm the validity of Hypothesis H6.

Data from the cities studied indicate that the implementation of digital art in public spaces is more prevalent in first-tier cities, with second- and third-tier cities lagging behind. Many new techniques and displays of digital art in public spaces are often first introduced in first-tier cities. Additionally, the implementation of digital artworks frequently requires substantial human and material resources. Therefore, economic considerations should be a priority when planning digital art in public spaces. Moreover, the alignment of the communication elements of digital artworks with their themes, and whether the presentation and interaction effectively engage users’ curiosity and enthusiasm, greatly affect users’ willingness to participate and the fulfillment of the artwork’s intended functions. Designers must skillfully leverage their imagination during the creation stage, fully consider human-computer interaction, and design digital artworks in public spaces that meet the required standards.

Analysis of user influence elements

While the influence of users on the willingness to participate is less than that of public space and digital art, users remain a crucial factor. Among users, the most significant influence comes from multi-sensory experiences, followed by the interpretation of the work and aesthetic ability. Psychological expectations and image experience have less influence. However, when considering the mediating effects of these five elements on willingness to participate, aesthetic ability has the greatest impact, followed by multi-sensory experience and psychological expectations. Work interpretation and image experience have a lesser effect, indicating that research should focus more on how users’ multi-sensory experiences and aesthetic abilities influence their participation intentions. These results also provide evidence for the acceptance of Hypothesis H4.

Multi-sensory experience is the result of the combined action of multiple senses, including vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. In the creation phase, designers should ensure that the interface of digital art in public spaces features clear composition, well-organized layouts, and high-resolution images to provide users with a comfortable and pleasant visual experience. Additionally, incorporating dazzling animations, realistic video effects, and smooth playback can enhance visual enjoyment, encouraging users to pause and interact. From an artistic practice perspective, appropriate background music and sound effects can enhance auditory enjoyment and contribute to a heightened sense of immersion. The tactile experience involves the interaction between the user and interface elements. While taste is an important aspect of art, it is not commonly incorporated into digital art in public spaces. However, some food-related digital artworks have begun to integrate gustatory elements, such as aroma, to create a richer sensory experience.

Aesthetic ability reflects a user’s capacity for aesthetic judgment, preference, and expression. A strong aesthetic ability enables users to recognize aesthetic value and create unique aesthetic experiences. Therefore, in the context of digital artworks in public spaces, users need a certain level of aesthetic ability to fully engage with the art.

Analysis of public space influence elements

The direct impact of public space on users’ willingness to participate in digital art interventions is significant, with a parameter estimate of 0.557, which is higher than the impact of digital art and user influence, thereby supporting Hypothesis H1.Among the factors influencing public space, scale has the largest impact, followed by accessibility. Human history, management and operation, and climatic conditions have smaller but relatively balanced influences. These elements also mediate users’ willingness to participate—partly through public space itself and partly through direct influence on public space. These results support the acceptance of Hypothesis H2.

Mediation analysis shows that scale has the greatest influence, followed by management and operation, and accessibility. Therefore, when integrating digital art into public spaces, it is crucial to first consider the scale of the space. Designers should evaluate scale from multiple perspectives and tailor it to local conditions to promote positive participation. Accessibility is also a critical factor; as C. Alexander noted, the first element of space is accessibility (C. Alexander, 2004). Hence, when implementing digital art in public spaces, designers must consider the convenience of access based on the intended exhibition effect. Effective participation requires strong management and operation, so designers should consider these aspects during the site selection and creation phases to ensure that digital art in public spaces can be sustained through continued user engagement.

Conclusion

Based on the design influence elements of digital art intervention in public space discussed in the previous chapter, this study approaches the analysis from the perspective of willingness to participate. Using Amos 24.0 software, a structural equation model was established to explore the relationships between public space, digital art, users, and their influence on the willingness to participate. The model also assessed the influence and relative weight of 15 specific elements, including scale, accessibility, and cultural history, on participation willingness. The results indicate that Hypotheses H1–H6 are all supported, and the relationships between the factors are significantly positive. Additionally, the mediating effects of these 15 elements on willingness to participate were examined. Our analysis reveals that accessibility and economic factors significantly drive willingness to Participate more than the aesthetic elements emphasized in prior literature. This finding addresses the traditional neglect of economic factors in art intervention studies, aligns with Bishop’s critical discussion on the capitalization of public art, and engages with Moreno’s participatory design theory. The research offers a novel theoretical framework for understanding public space governance in the digital age and provides empirical support for urban digital inclusion policies. However, limitations exist: the sample is predominantly from eastern developed cities (62% coverage), which may limit the generalizability of the conclusions, and cross-sectional data cannot capture the dynamic evolution of user behavior. Future research should extend to county and rural spaces, establish long-term tracking databases, and delve deeper into issues of technological ethics and the digital divide.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the follow-up work of the research topic involved has not been completed yet, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yu, L. Discussing the publicness of public Art aided by virtual spaces. J. Southwest. Univ. (Social Sci. Edition). 47(06), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2021.06.021 (2021).

Chen, X. L. From audience to user: grasping three dimensions. Media Forum 3(16), 127–129 (2020).

Jiang, X., Wang, F. & Jiang, Z. Study on the path of continuous participation of digital Art in public space in 6G IoT communication. Wirel. Commun. Mobile Comput. 1109922, 12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1109922 (2022).

Lee, J. W. & Lee, S. H. User participation and valuation in digital Art platforms: the case of Saatchi Art. Eur. J. Mark. 53, 1125–1151. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-12-2016-0788 (2019).

Anderson, J. C. & Gerbing, D. W. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 (1988).

Li, M. X. Research on the revitalization and utilization of key buildings in historical and cultural blocks based on digital media technology (Doctoral dissertation). North China Univ. Technol. (2021). https://doi.org/10.26926/d.cnki.gbfgu.2021.000268.

Chen, X. Combination of points and surfaces, virtual and real intersection: application of digital museums in the display of historical buildings in Beijing’s old city. In Proceedings of the Beijing Digital Museum Seminar. Beijing Association for Science Popularization (2019). https://doi.org/10.26914/c.cnkihy.2019.059723.

Chen, L. Art in the digital age: constructing interfaces for urban perception. Explor. Free Views. 08, 130–140 (2021).

Chen, W. Q. Application Research of Experiential Interactive Media Landscape Devices in Urban Public Spaces Based on Intelligent Technology (China University of Mining and Technology, 2021).

Chen, X. G. Aesthetic transformation and theoretical expansion of new media Art under digital technology. Social Sci. Front. 4, 180–188 (2021) (In Chinese).

Wang, F. Research on the interaction design of urban public art in the context of digitalization (Master’s thesis). Jiangnan University (2010).

Pan, P. C. Digital participation: public Art in virtual spaces. Public. Art 3, 103–107 (2021).

Dong, Y. & Ding, W. X. Application of digital media technology in public Art design. J. Nanchang Normal Univ. 39(06), 50–52 (2018).

Zheng, J. From non-solid to non-material (Doctoral dissertation). China Academy of Art (2018).

Liu, J. W., Wang, W. J. & Chen, T. The impact of digital information technology on urban public Art. Art Criticism 9, 100–102. https://doi.org/10.16566/j.cnki.1003-5672.2014.09.003 (2014).

Cai, S. X. Research on the field nature of digital public art (Doctoral dissertation). Shanghai University (2011).

Littwin, K. & Stock, W. G. Signaling smartness: smart cities and digital Art in public spaces. J. Inform. Sci. Theory Pract. 8(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1633/JISTaP.2020.8.1.2 (2020).

Borysova, S. et al. Analysis of the impact of the digital revolution on creativity in contemporary art: technological changes, interactivity, and virtual aesthetics. Synesis 16(1), e2951 (2024).

Gullström, C. et al. Presence design mediated spaces extending architecture (Doctoral dissertation). Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden (2010).

Wagner, T. & Praxmarer, R. Urban playfulness: fostering social interaction in public space. Mensch & Computer–Tagungsband.. https://doi.org/10.1524/9783486781229.201 (2013).

Chen, K. et al. Towards a typology for playable digital interventions in urban public spaces. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct) (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISMAR-Adjunct.2019.00123.

Nardelli, E. A classification framework for interactive digital artworks. User Centric Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-35145-7_12 (2010).

Chang, L. M. On digital media Art and its expressive elements. Wisdom 7, 236 (2013).

Wang, F. & Guo, W. M. Interaction concept and digital public Art in cities. Art Hundred Schools. 26(S2), 97–100 (2010).

Luo, D. Research on the application of digital information in urban public Art design (In Chinese). Beauty Times (Urban Edition). 11, 61–62 (2020).

Huang, M. F. New paradigm of narrative art: the cultural communication function of contemporary digital games. Media Forum. 7, 13. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2096-5079.2024.13.001 (2024). (In Chinese).

Qin, C. Research on the cultural value of digital media Art. Art Apprec. 3, 175–176 (2016).

Wei, H. L. Discussing the aesthetic characteristics of design in the digital Art era. Art Des. (Theory). 2(5), 98–100. https://doi.org/10.16824/j.cnki.issn10082832.2013.05.025 (2013).

Ruan, P. J. & Liang, J. L. Economic value assessment of digital media Art in the new era. Fortune Times 12, 163. (2019).

Poposki, Z. Corpus-based critical discourse analysis of NFT Art within mainstream Art-market discourse and implications for the political economy of digital Art. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1296. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03827-3 (2024).

Jiang, L. On immersive Art in the digital technology scenarios of the 5G era. J. Shandong Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 6, 47–57 (2019). (In Chinese).

Li, Z. Technology as a new tool and medium for art: a review of experimental art, digital art, and animation at the 14th National Art exhibition. Art Observation. 11, 33–35 (2024).

Wang, Y. Z. On the impact of virtual photography technology on viewer’s time perception. Mod. Film Technol. 12, 30–37 (2018).

Zhong, Y. Q. Immersion and distance: aesthetic illusion in digital Art. Acad. Res. 8, 170–176 (2019).

Zhu, H. W. Research on sustainable design principles and methods based on user perspectives. Sci. Technol. Vis.(16), 224–225. https://doi.org/10.19392/j.cnki.1671-7341.201916200 (2019).

Deng, J., Wang, R. & Sheng, P. P. Research on the influencing factors of archive website service quality from the perspective of user perception. Archives Sci. Res. 04, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.16065/j.cnki.issn1002-1620.2018.04.011 (2018).

Shen, H. Z., Yuan, Q. J. & Xiao, G. F. Quality evaluation of Chinese crowdsourcing websites from the perspective of users. Mod. Inform. 37(11), 10–16 (2017).

Yao, Y. Research on the evaluation system of group-buying websites based on customer satisfaction (Master’s thesis). Xidian University (2012).

Tsiaousis, A. S. & Giaglis, G. M. Mobile websites: usability evaluation and design. Int. J. Mobile Commun. 12(1), 29 (2014).

Carta, T., Paterno, F. & Santana, V. F. D. Web Usability Probe: a tool for supporting remote usability evaluation of websites. In Proceedings of the Ifip Tc 13 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 46 349–357 (2011).

Liu, Y. X. Research on the evaluation index system of graduate website from the user’s perspective (Master’s thesis). Hebei University (2019).

Roberts, B. Entertaining the community: the evolution of civic ritual and public celebration, 1860–1953. Urban History. 44(3), 444–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926816000511 (2017).

Bellisario, S. The artist as ritual maker, creatrix and magical healer: symbolic artmaking and participation for the purpose of cathartic release. Peace Rev. 35(2), 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2023.2190839 (2023).

Stets, J. E. & Burke, P. J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychol. Q. 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870 (2000).

Zhao, H. & Zhang, W. Research on the perception of cloud computing among accounting practitioners in Township enterprises. Chin. Townsh. Enterp. Acc. 8, 249–250 (2015).

Wang, Q., Liu, Z. & Hu, J. Effects of color tone of dynamic digital Art on emotion arousal. In Entertainment Computing – ICEC 2022. ICEC 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13477 (eds Göbl, B., van der Spek, E., Hauge, B. & McCall, J. R.) (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20212-430.

Jiang, Z., Jiang, X., Jin, Y. & Tan, L. A study on participatory experiences in cultural and tourism commercial spaces. Heliyon 10, e24632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24632 (2024).