Abstract

Over the past five decades, China has witnessed rapid urbanization. Since the 1970s, Beijing’s population has grown 150%, its subway network expanded from a single line covering 10.7 kilometers to 27 lines spanning 836 kilometers, and its housing stock has increased by 95.3%. These significant urban changes have paralleled national economic and social transformations, notably after China opened its markets to international trade in 1978. This study examines the repercussions of these broad urban and socio-political changes on individual domestic spaces in Beijing. Analyzing floor plans of over 2000 apartments built between 1970 and 2020, we introduce a computer vision-aided methodology to quantitatively assess the distribution, intensity, and nature of domestic activities, employing isovist analysis while considering property size and age. This approach facilitates a nuanced understanding of changes in visual accessibility for specific room types, thereby shedding light on the evolution of social life as reflected in the spatial configurations of the pre- and post-housing privatization eras. Our findings show a trend in the isovist intensity of living rooms, dining rooms, and kitchens, indicative of shifts toward privacy and mixed-use spaces, shaped by household occupancy patterns. By harnessing numerous online home interior images, this study underscores the potential of integrating large-scale imagery data with computer vision technology to yield profound insights into architectural and domestic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 1978, China has experienced rapid urbanization. The urbanization rate rose to 39.5% by 2019, with projections indicating it could reach approximately 80% by 2050 (Song & Zhang, 2002; Hamnett, 2020). This transformation, which followed the country’s economic expansion (Gong et al., 2012; Yao et al., 2014), has been characterized by large-scale internal migration and a notable rise in living standards and incomes. To accommodate the burgeoning urban population, between 1996 and 2014 China witnessed the average annual increase of 9.3% in urban residential building floor space (Pan et al., 2020). This growth has led to a complex interplay of factors, such as rising housing prices, per capita disposable income, and per capita living space (Ren & Folmer, 2022).

Urban planning and design studies have primarily focused on the public sphere (Whyte, 1980; Nasar, 1990; Douglas et al., 2019; Miranda et al., 2021), whereas, we argue here, the study of domestic life and housing interiors holds equal importance. Housing, which is the fundamental unit of society and urban space in economic, cultural, and psychological terms (Josselyn, 1953; Scott, 1979), is pivotal in facilitating family activities. Previous studies have primarily examined housing physical attributes and housing prices (Palmquist, 1984; Sirmans et al., 2006; Zhang, 2022), leaving aside the understanding of how macro-urban development impacts private life, especially amid rapid urbanization.

This paper proposes to measure how the private ___domain of housing has been profoundly impacted by the major socio-political shifts in China since 1978, a period that also marked a significant turning point in the urban domestic landscape. This era was characterized by the introduction of Western lifestyles, household appliances, and the interplay between public and private spheres, bringing about transformative changes in urban apartments. During the pre-reform period, these apartments, primarily constructed before the 1990s, were designed, built, and allocated through the work-unit system, also known as Danwei (Bray, 2005). This system was integral to China’s economic, social, and spatial organization, influencing the organization of workers’ social lives within the unit (Wu, 2018).

In Chinese cities, apartments are the predominant housing typology for a growing urban population. Apartments’ functional layout shapes collective private lives and mirrors broader urban development (Saraiva et al., 2019). To explore the transformation of domestic activities and spatial configuration, we have compiled a dataset of over 2000 apartment floor plans in Beijing, built between 1970 and 2020. Our approach combines computer vision and isovist methods to analyze the distribution and intensity of six primary domestic functions: living room, dining room, kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, and balcony.

While previous computer vision research on housing floor plans primarily focused on efficiency improvement and automation in design practices (Wu, 2020; Carta, 2021; Rodrigues & Duarte, 2022), our study delves into how macro-scale housing policies influence the framework of domestic activities within urban homes. By integrating computer vision techniques with the architectural design significance of floor plans (Brooker & Stone, 2009; Mitton & Nystuen, 2021), we explore how domestic spatial configuration may reflect broader economic, social, and political shifts over time. Specifically, we study

-

How changes in urban apartment layouts respond to broader macro-scale urban policies and some societal transformations.

To answer this question, we investigate how apartment size, influenced by shifts between work-unit and market-oriented design decisions, impacts the distribution of visual accessibility within homes. We also explore design trends before and during housing reforms, with a focus on room types included during the ‘Danwei’ period. Finally, we examine how the transition in layout design after 2000 reflects changes in living culture in Beijing households. Through this lens, we seek to uncover the interaction between individual and community life during the work-unit period and to offer insights for sustainable home interior design in the future.

Material and method

Study area: Beijing

Chinese cities, especially Beijing, have undergone significant transformations in the past five decades. Characterized by planned and market-oriented approaches, they have dramatically influenced the post-socialist urban landscape (Yeh & Wu, 1999; Zhang, 2000; Wu et al., 2006). A critical factor in this transformation has been housing, which was heavily shaped by the Danwei, or work-unit system (Wu, 1998; Li & Gou, 2020). This system has not only molded the urban morphology of Chinese cities but also profoundly impacted the domestic life of urban residents (Bonino & De Pieri, 2015). Beijing’s rapid development post-2000 marked by socio-economic growth, cultural diversity, and a technology-led lifestyle, has changed neighborhood design and individual housing units.

By 2022, Beijing’s total completed residential space had reached 10.96 million square meters, a 384% increase from 1990 (Beijing Statistical Yearbook, 2023), with apartments being the predominant housing type. This construction boom was coupled with the city’s population growth to 21.9 million by 2020 (a 101% increase from 1990, according to the Beijing Statistical Yearbook, 2023). In addition, Beijing’s hosting of significant global events in the past two decades, such as the 2008 Summer Olympics and the 2022 Winter Olympics, has further influenced its urban landscape’s cultural and socio-economic development. By analyzing home interiors in Beijing, we can uncover how urban life transformations are revealed from a housing perspective over time, providing valuable insights for future developments.

Dataset

For this study, we sourced floor plan imagery data from BeikeFootnote 1, a leading online real estate platform in China. Established in 2010, Beike provides comprehensive information on both second-hand and new housing for sale or rent. The data utilized in this paper includes floor plans from second-hand apartments listed for sale, and includes information about building age, price, and ___location.

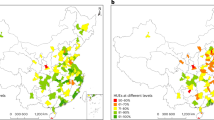

Our initial collection comprised over 4000 properties. We refined the dataset to include only properties with complete information, resulting in 2200 properties across 1436 communities, ensuring comprehensive spatial and temporal coverage in Beijing from 1970 to 2020 (Fig. 1). The sampled apartments exhibit spatial dependency on the main ring roads in Beijing, with older apartments typically found in the inner areas (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we categorized apartments into four distinct groups according to their square footage, utilizing quantile values as the basis for classification. Apartments occupying the uppermost 25% in terms of square footage were designated as “large,” while those in the lowest 25% were labeled as “small.” Notably, the inner-city district, which predominantly features residences from the pre-reform era, predominantly consists of comparatively petite living spaces (measuring under 59.07 square meters). Conversely, residences constructed after the year 2000, tend to occupy a larger footprint (exceeding 95.83 square meters) or fall into the mid-size range (spanning from 76.34 to 95.83 square meters). These newer apartments exhibit a more dispersed spatial distribution in comparison to their pre-reform counterparts, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

Despite the extensive coverage that Beike provides, we acknowledge the potential biases due to its commercial nature, as highlighted in previous studies (Zhang et al., 2022). To ensure the objectivity of our research, we concentrated on attributes less susceptible to market dynamics, such as the layout and age of the apartments. While biases related to the trading behavior of housing and the quality of indoor images might exist, we anticipate these to have a minimal impact on the isovist quantification of domestic spaces. Additionally, the quality of images as research data can be compromised by their commercial nature, including issues like logo overlays on floor plans, which highlight the general limitations of using non-research-specific image data.

Our study utilizes two attributes: the square footage and the construction year of the apartments. Over time, fewer small apartments were built, while there was an increase in the construction of larger apartments (Fig. 2). Although we collected data on price per square meter, this variable demonstrated limited relevance to the year of construction.

To address the primary objective of our study, which is to explore how interior housing design reflects Beijing’s macro-political movements, we analyze domestic spaces using isovist quantification. We control this analysis by square footage and age of the apartments, as critical variables directly linked to the evolving architectural trends and socio-political context.

Method

How floorplan and isovist cooperated in understanding socio-spatial meaning of space

Isovist analysis, mainly utilized in architectural and built environment research, represents all visible points from a given ___location in space, offering insights into how individuals might perceive and navigate architectural spaces (Benedikt, 1979; Turner et al., 2001). This method has been valuable in understanding the relationship between architectural form, vision, and human behavior (Batty, 2001; Ostwald & Dawes, 2013). Isovist is instrumental in establishing Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) as one of the space syntax tools, initially introduced by Braaksma and Cook (1980). VGA allows building and urban environments to be consistently represented from a visual accessibility perspective. The adjacency matrix, constructed based on isovists, is key in quantifying the visibility of a given space, enabling further comparisons. The distinctiveness of space utilization, analyzed through VGA, allows the relationship between culture and behavior to be established.

Hillier et al., (1987) investigated domestic patterns mirrored through home interiors. They discussed the configuration of 17 rural houses by relating the geometry of layout, behavior, and room functions. The impact of the physical setting of interior space on spatial configuration was examined, suggesting that these configurations may result in cultural practice differences in everyday life. A justified graph supported comparative studies, demonstrating how space could be studied through natural movement representation. It also points out how isovist could be introduced in the field of architectural interior research. Urban interiors play a vital role in people’s everyday living experiences and accommodate various types of interactions between both moving and stable objects, making isovist analysis an important tool for perceiving about the prototypes of these interactions. Batty (2001) posits that our perception of movement within isovist fields is influenced by their geometric properties. Isovist analysis reveals that visual fields have distinct forms within the morphologies of built environments. Various indoor spaces, including workplaces (Sailer et al., 2021), commercial spaces (Kwon & Sailer, 2015), museums and galleries (Wiener et al., 2007; Li & Huang, 2020), and houses, have been examined using isovist analysis. This method helps establish spatial-behavioral relationships that reflect the cultural and social meanings of these spaces. Furthermore, Benedikt and McElhinney (2019) emphasize how advancements in computing could enhance the application of isovists in generating building layouts in the future, aiming to improve the quality of space. By preserving the isovist’s capability to decode the interconnection between space and behavior, a more dynamic understanding of the built environment could be revealed, aiding in the creation of more sustainable spaces.

Previous research has predominantly focused on utilizing isovists in various public interior spaces. It is crucial to emphasize that collective home interior spaces occupy a significant portion of urban environments, and individuals typically spend over 90% of their time within indoor Klepeis et al., (2001). The isovist, which serves as a bridge between geometric features and social interactions within the home, may offer deeper insights to future development of design. With recent advancements in floorplan automatic generation (Merrell et al. 2010; Wu et al., 2019; Hieu and Thuy, 2024), large-scale isovist analysis can be enabled by advances in computer vision and deep learning technology, potentially leading to more spontaneous and effective strategies in the design and construction sectors.

In this study, we have taken a unique approach by combining classical computer vision techniques such as erosion, dilation, edge detection, and Hough line transformation. This combination has allowed us to extract the floor plan layout and identify room boundaries. Moreover, we have developed a novel algorithm to reconstruct isovist heat maps from the floor plan images. To delve deeper into the floor plan layout analysis, we have employed YOLOv8 object detection network to detect various layout sections, like bedrooms, living rooms, and kitchens. This has empowered us to thoroughly analyze changes in isovist values across different rooms designated for domestic functions over the years, as well as conduct a study on an urban scale (Fig. 3).

Pre-processing images

To reconstruct the isovist heatmap from floor plan we first removed any watermark logos in the image by detecting and analyzing the morphological structures associated with the logo. This was followed by extracting the floor plan’s outline by detecting all the contours within the layout plan. In this context, contours represent curves that connect continuous points along a boundary with the same color or intensity. For RGB floor plan images, we focused on the outline boundaries represented by a black color (RGB: (0, 0, 0)). We translated the RGB floor plan image into a binary image using an inverted binary operation with a threshold value of 230. Values below 230 were set to black based on empirical results from 10 floor plan images. The resulting binary image was then subjected to a contour detection algorithm, such as the one available in the OpenCV library (Bradski, 2000). Given that a floor plan can contain multiple contours representing room boundaries or other objects, we selected the most prominent contour as the outline of the apartment, the primary spatial boundaries of interest (Fig. 4).

The room boundaries are crucial to determine the visual fields within apartments. Two morphological operations are employed for this task: erosion and dilation. Initially, the erosion operation was applied to the image, aimed at gradually removing the foreground object’s boundaries, which in this case were the walls or room boundaries in the floor plan images. Erosion reduced the thickness of the room boundaries, simplifying the image and mitigating thickness variations in the walls, if present. Following the erosion step, we applied the dilation operation, which counteracts the effects of erosion by expanding the size of the foreground object. Through dilation, we reconstructed the primary structure of the eroded room boundaries while simultaneously filling in any gaps created during the erosion process. The resulting image, obtained after the sequential application of erosion followed by dilation, is shown in Fig. 5b.

In the image produced by the erosion-dilation operation, the Canny Edge Detector (Canny, 1986) plays a pivotal role in extracting all the present edges, as shown in Fig. 5c. Following this, the Hough Lines algorithm (Duda & Hart, 1972) is instrumental in identifying and obtaining the coordinates of the room boundaries.

Due to noises present in the image, particularly around complex features such as doors and steps, there have been some inaccuracies. We implemented a series of preprocessing techniques, including morphological operations such as erosion and dilation, to reduce noise and enhance the structural clarity of the floor plans. Our edge detection and contour algorithms are also best tuned to handle typical variations in floor plan images. Despite these efforts, certain complexities inherent in the public dataset/images may still result in minor inaccuracies.

Algorithm for isovist count

The algorithm reconstructs the isovist heatmap from the floor plan image and relies heavily on a grid-based approach. The floor plan is segmented into a size m x n grid, where m = 30 and n = 40 (Fig. 6). The selection of m and n values (m ≠ n) is based on empirical experiments. It eliminates redundant intersections, such as lines along diagonals, if m and n are identical.

The original resolution of all floor plan images is 1000 pixels × 750 pixels. For each grid in the floor plan, lines are drawn from the center point to every other center point. If a line intersects with a wall, it is terminated at that point (Fig. 4). This meticulous process guarantees that the lines accurately depict the unobstructed visual connections within the floor plan. Once the lines have been drawn from each grid, we count the number of intersections at different pixel values within the floor plan. This step enables us to measure the visibility and accessibility of each pixel within the floor plan. We apply a Gaussian filter to achieve a more refined representation of the isovist heat map. This filter effectively minimizes noise and enhances the overall quality of the reconstructed isovist visual map.

Isovist count in different sections of the floor plan

To investigate the variations in isovist intensity, which shows the total number of intersections of lines (Fig. 6) at different pixels in an apartment, among different sections of the apartment, such as a bedroom, living room, etc., we employ an object detection approach. Each apartment section, including the bathroom, kitchen, bedroom, living room, dining room, and balcony, is detected based on specific features in this approach. For instance, a bed icon in the image is used to detect a bedroom, while a couch icon is used as a feature to detect a living room.

To facilitate this detection process, we create a dataset consisting of 500 images, where each image is annotated with bounding boxes around the relevant features (e.g., bed, couch) along with their corresponding class labels. We trained a state-of-the-art object detection network, YOLOv8 (Jocher et al., 2023), pre-trained on the COCO dataset (Lin et al., 2014), using this dataset of 500 images. The choice of YOLOv8 was due to its proven efficiency and accuracy in object detection tasks. There is slight variation among these features when identifying room sections. For instance, beds may differ only slightly in terms of orientation, necessitating a limited number of images to achieve high accuracy.

Once the detector is trained, we utilize it to perform inference on the floor plan images. The isovist intersection values are then summed within the detected bounding boxes of each room section, such as the bedroom or living room. To have isovist values that are comparable across different room sections, regardless of their size, it is necessary to normalize the sum of the isovist values. This normalization is done by dividing the sum of isovist values by the area of the corresponding bounding box in square pixels. Additionally, when a layout contains multiple bedrooms, we calculate the average normalized value of the isovist count for these bedrooms. These normalized values serve as the basis for subsequent calculations and analysis (Fig. 7).

The Isovist Intensity Score (IIS) serves as the primary metric in this paper for elucidating the features and transformations of housing interiors. This score quantifies the normalized mean visual accessibility of rooms with design features such as openness, connectivity, and continuity. The floor plan, which symbolizes the assembly of these rooms, could also be understood consistently. The distribution of IIS within apartments clarifies the relationship between functions and rooms in terms of visually suggested potential natural movement. However, decoding the interior spatial system through isovist analysis may reflect collective individual life events within homes, providing a foundation for discussing the cultural and social meaning of these homes. The actual domestic activities and behaviors are not directly suggested through this approach.

Identifying the most significant layout design

The isovist map represents a floor plan by providing information about the visual accessibility of residents. This characteristic of the isovist map, which is a matrix representation of isovist intensity based on the geometric characteristics of the floor plan, allows computer vision to extract features more easily. This facilitates a more robust analysis of its significance. Therefore, this study utilizes the VGG16 model, trained on the ImageNet dataset (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014), to identify the most significant isovist maps. Features were extracted from these images, and a similarity matrix was constructed to create a graph representation. The well-established PageRank algorithm, proposed by Page et al. (1999), was then applied to calculate the representativeness scores of each image. Isovist maps with the highest representativeness scores for each construction period were calculated to identify the corresponding floor plans, regardless of the apartment’s square footage. Five-period clusters were defined based on different phases of housing reform, which are divided into before 1980, between 1981 and 1990, between 1991 and 2000, between 2001 and 2010, and after 2010.

The isovist heatmaps show the distribution of IIS within each apartment, with colors representing intensity values. We employed this analysis pipeline to examine the evolution of apartment floor plan layouts at 10-year intervals, from 1970 to the present. We overlay of the isovist map on the actual floor plan design, representing the IIS distribution among various spaces within an apartment. For instance, a dining room represented by a warm tone on the isovist map indicates a higher IIS value, suggesting more robust visual integration and connectivity within that space. Conversely, cooler tones indicate lower IIS values, suggesting less visual integration or connectivity.

Comparing IIS and floor plan designs over time offers a unique perspective on how domestic spaces have evolved. The focal point of each isovist map reveals the space with the highest potential for integration, typically characterized by less obstructed areas, whereas spaces with more winding and closed configurations suggest lower integration. By assigning domestic functions to these spaces, we can quantify the interrelationship between different functions based on visual accessibility. This comparison provides insights into the design trends and offers evidence of potential lifestyles during specific time periods.

Results and discussion

The emerge of diversified apartment in size

The late 20th century marked a pivotal shift in China’s housing development, driven by the marketization of land and housing privatization (Li, 2000), transitioning from the work-unit system to a market-oriented one. During the transformation period, Beijing experienced an increase in total residential building construction, which began in the 1980s and reached its peak in 2005 (Beijing Statistical YearBook, 2020). Particularly important for our analysis, there was a decrease in the construction of small apartments and an increase in the number of large and middle-size apartments (Fig. 8).

In addition to the changes in construction tendencies regarding apartment sizes, the IIS distribution among room types varies within large and small apartments, potentially resulting in a disparity in household spatial usage on a daily basis (Fig. 9). Room types where different essential domestic activities are performed stand out due to their different IIS performance, with the living room and dining room being the primary driving forces. In contrast, the statistical relationship of IIS in other room types—namely the kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, and balcony—demonstrates less variation with the apartment’s size. Notably, living rooms in the largest apartments exhibit a higher variation in IIS than dining rooms. A closer IIS distribution could be found in the smallest apartments, which the sole function of the living room or dining room could cause. In other words, a more blended domestic activity is typically observed in smaller apartments’ combined living-dining room space. Furthermore, the increase in the number of larger apartments after 2000, as illustrated in Fig. 8, indicates a potential for enhanced diversity and visual accessibility in living room utilization. Additionally, the mixed-use trend is more commonly observed in smaller apartments, which were likely built during the Danwei period.

While the living room and dining room in larger apartments built after 2000 generally have a much higher IIS compared to smaller apartments built before 2000, less disparity in the distribution of IIS is observed within bedrooms and balconies between small and large apartments, as well as between older and newly built apartments (Fig.10). Additionally, some large properties built before 2000 also demonstrate consistently lower IIS for the living room (Fig. 10a), dining room (Fig. 10b), kitchen, and bathroom (Appendix 1) when compared to large properties built after 2000. Furthermore, higher IIS can be found in bedrooms and balconies of small apartments built during the 1970s and 1980s, which coincides with the Danwei period.

Figure 11 illustrates how apartment size impacts the distribution of Isovist Intensity (IIS) among different room types, indicating potential influences of domestic activities shaped by housing reform policies. With an even sample size between the Danwei and Post-Reform periods for both large and small apartments, we observe that the large apartments (left plot) show a greater disparity in IIS values across different room types compared to the small apartments (right plot). Specifically, the IIS values for the living room and dining room are significantly higher in the large apartments built during the Post-Reform Period compared to those built during the Danwei period. In contrast, small apartments exhibit relatively consistent IIS values across room types, except for the dining room, regardless of the construction period.

A construction of larger apartments starts rise dramatically at 1998, indicating a significant shift in housing design and construction due to the implementation of various housing reform policies in Beijing. However, the function of specific rooms could potentially influence the intensity of this transformation, with living rooms and dining rooms showing greater variability compared to bedrooms and balconies (Fig. 10).

The construction of urban housing in Beijing responded sharply to national socio-economic movements, most notably in the size of the apartments being built. This shift has been followed by increasingly diversified interior layouts that are closely linked to individuals’ daily activities from a functional perspective. The varying sizes and relationships between room types illustrate how interior spaces, as the micro-scale manifestation of housing design, reflect the broader macro-scale movements in urban policies and social transformations. The physical environment of these homes becomes a mirror for the evolving urban domestic life, demonstrating the interplay between micro and macro urban development and how it shapes urban lifestyles.

Housing reform in China: a changing domestic landscape within urban homes

Following the 1978 opening policies by the central government, the housing reform in China primarily occurred in the 1980s and the 1990s. In 1988, after the launch of ‘The Urban Housing Reform Program’ and following several pilot experiments, a nationwide housing reform which used market mechanisms was initiated—specifically with the ‘Regulations on the Administration of Urban Real Estate’, introduced in 1991. This period also marked the starting point for foreign investment in the Chinese real estate market (Jiang et al., 1998). Meanwhile, a dual system for the housing market was introduced to facilitate the period of transitional decentralization (Huang, 2004).

The results from the previous section are sensitive to the time interval, particularly during the transition between the Danwei and post-reform periods, with the turning point in 1998. A growing number of housing constructions, accompanied by an increasing size of apartment constructions led by policy movements, have resulted in a transformation of interior layouts. This material alteration within homes serves as a bridge connecting individuals to the urban development process. It could be caused by the shift in housing construction stakeholders and ownership, which has not only influenced residential space at the urban scale but has also brought design diversity in housing interiors. The requirement imposed by the government for development companies to construct new housing in the public sector has led to the transfer of design responsibilities, resulting in an increased variety of architectural styles and interior designs (Yeh & Wu, 1996). With the growing size of household private space after the reform, the increasing visual integration among all room types is observed from the mean value of IIS in large apartments. A more heterogeneous housing type emerged due to implementation several important policies during the 1990s. These policies include the Urban Real Estate Management Law in 1991, which allowed land use rights to be obtained through market mechanisms; the comprehensive implementation of the housing provident fund system in 1994; and the official end of welfare housing allocation in 1998. These top-down actions in the Chinese housing sector significantly impacted the physical space of home interiors, deeply influencing people’s lives at that time and continuing to do so today.

Decoding home interior under “Danwei” system

The floor plan design in the 1970s exhibits homogeneity, highlighting that both architectural and interior housing designs during the work-unit period were standardized (Lin, 2014). Small living rooms are prevalent in floor plans predominantly constructed during the late 1970s, with a specific interior design term ‘Fangting’ (Quadrangle room). These rooms were not allocated specific domestic functions due to their limited size (Fig. 12a–c). Despite the floorplan data acquired in this study showing that ‘Fangting’ could be used as either a living room or dining room in contemporary times, it was not designed for hosting guests but served as a transitional space between the outside and inside of homes. Notably, the main bedrooms in these identified floor plans exhibit a high level of visual integration compared to the living rooms, where imply a higher concentration of internal social interaction for households. In Beijing during the 1970s, however, the main bedroom was a highly connected space within the home, also extended by a balcony. Despite the focal point for visual accessibility being in the transitional space, which lacks a specific function, the interior layout of this period can be characterized as a 3-branch structure.

a–c A unified room layout is observed during the 1970s, leading to a concentrated IIS distribution at the transitional space between the living room and bedrooms. d–f A similar room layout is observed in the 1980s, with comparable geometric characteristics, while the IIS distribution becomes more distinct across room types. g–i Increasing diversity in floorplan design in the 1990s, followed by more varied IIS heatmaps, influencing the distribution of IIS across room types. Please visit Appendix 2 for the top 5 most significant interior layout designs for the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s.

During the 1980s, layout designs commonly featured relatively larger living rooms than in previous periods. Both one-bedroom and two-bedroom layouts were prevalent at this time. The overall layout of the apartments typically presented a long and narrow geometric shape, a characteristic common across all identified layout designs, as depicted in Fig. 12d–f. The spatial relationship between the living room and bedroom demonstrated higher flexibility during the 1980s. This flexibility resulted in less uniformity in the layout of functions, even though the room layouts remained similar. In the 1980s, a typical layout consisted of two bedrooms connected by a small living room, often called the “glasses” apartment. A distinctive feature of the layout designs in the 1980s included a balcony attached to the main bedroom, a feature not commonly seen in floor plans from the 1970s. The most significant layout design identified clarifies what Fig. 10 illustrates regarding the IIS distributions in bedrooms and balconies of small apartments built before the 2000s. During the later Danwei period, balconies were frequently attached to main bedrooms, resulting in a high correlation in IIS (Fig. 13b), providing primary spaces for family gatherings. These areas accommodated various domestic activities such as dining, gathering, sleeping, and working (Lu, 2003). The findings, which identify significant layout designs as shown in some of the layouts in Appendix 2 (1970s), are coherent with existing literature and argue for the primary social function of the main bedroom in homes built during the Danwei period. For instance, in the most representative layout designs of the 1970s, despite the highest IIS being found in transitional spaces (both corridor and ‘Fangting’ areas), the main bedroom tended to be the space receiving the highest IIS where actual domestic functions were allocated.

Correlation matrix between domestic functions’ IIS during the 1970s (a), 1980s (b), and 1990s (c). a Negative correlation between living room and dining room IIS. b Continued negative correlation between living room and dining room, with a positive correlation between bedroom and balcony IIS. c Strong positive correlation between kitchen and bathroom IIS, indicating an increase in both areas’ IIS.

The increasing diversity in layout design, as shown in Fig. 12g–i, provides further evidence of the impact of the housing marketization in China during the 1990s. This diversity includes configurations such as one-bedroom, two-bedroom, and three-bedroom layouts, resulting in dynamic distributions of isovist intensity among domestic functions. In particular, the living room or living-dining combined room tends to exhibit the highest visual accessibility, indicating a greater potential for social integration within the household. The evolving character of living rooms in Beijing homes has also led to a structural transformation, wherein the living room tends to become the central hub for domestic functions, facilitating easy access to all other areas. Consequently, the transitional spaces that once served as terminals between functions are gradually fading away, giving rise to a more direct spatial connection between the living room and other domestic functions (Fig. 12h). While there may be fewer changes in layout design during the 1990s, a notable correlation can be observed between the kitchen and bathroom. (Fig. 13c).

An open space, typically located at the entrance of the apartment and referred to as ‘Fangting,’ was featured in layout designs from the 1970s. This area served as a transitional space between public and private life within the household. In modern living, this space is used either as a living or dining area, resulting in a strong negative correlation between these functions (Fig. 13a, b). The previously designated ‘Fangting’ functioned as a family sub-center at the entrance area, which also reflects a characteristic domestic setting in Beijing today. The relatively high positive correlation between bedrooms and balconies indicates a shift in design trends and a growing demand for quality private family life (Fig. 12b). Observing the living ___domain within homes from the perspective of Danwei highlights a movement between public and private living spaces encouraged by interior design. Home designs played a crucial role in balancing individual and institutional needs.

A significant development in home construction during the 1990s was driven by advancements in building technology, particularly installing water supply and drainage systems inside homes. The increase in IIS of kitchens and bathrooms significantly during this period could result from their more direct spatial relation with the living room (Fig. 12g–i), reflected through their strong positive correlation in Fig. 13c. This growing integration between service functions and residential life was promoted under broader social, technological, and political movements.

Apartment layout reflects and organizes the everyday living practices of urban dwellers. It has been a key indicator of the changes in Beijing’s urban homes from 1970 to 2000. The transfer of design and construction rights from work units to the private sector, a significant aspect of China’s housing reform, reshaped how rooms are connected and introduced new room types, such as the living room and bathrooms. These newly emerged spaces reorganized essential activities like gathering, dining, sleeping, and bathing, allowing the living culture rooted in the work-unit era to evolve. However, the living room is not entirely new but rather a potential evolution of the earlier Fangting found in pre-reform Beijing apartments, reflecting the essential need for gathering. This study posits an approach to how living culture is produced through the ongoing interplay between space and human needs, suggesting that living culture emerges through the spatial practice of essential everyday activities.

Departure from the unification of living

The ideology of the Danwei was implemented in both the working and living realms after the establishment of the People of Republic of China in 1949. Housing in Beijing under the work-unit system was considered a subsidy and was designed and constructed by the Danwei itself (Lu, 2003). The Danwei cared for all aspects of workers’ lives, including providing daily necessities and furniture. A uniform design of residential architecture for households was evident in the building facades and the layout of domestic functions. The design of a typical work-unit apartment featured a large bedroom and a “Fangting”. However, social life primarily occurred between the working and living spaces within the Danwei, and homes were not considered places for external social activities but for family gatherings (Bjorklund, 1986).

Conversely, a hierarchical functional structure was exhibited within a work-unit neighborhood, where major contemporary domestic activities were allocated to public areas, served by dining halls, bathhouses, and ballrooms. The new generation of work-unit residents also attended the same educational facilities. Shared life experiences were encouraged by the socialist setting of the work-unit neighborhood, where the home was instrumental in involving individual families in the community. The social and spatial setting of the Danwei supported the formation of the new geodemographic structure of modern Beijing. The relaxation of migration controls and economic liberalization in China during the early 1980s led to a greater mix of the urban population, resulting in the formation of new socio-spatial communities (Ma & Xiang, 1998). During this process, the Danwei were officially established communities hosting the newly immigrated population, typically skilled, governmental, and intellectual workers. While a social mix was promoted within work units among households with different backgrounds, social segregation resulted from the broader context of urban community reform in Beijing. While a social mix was promoted within work units among households with different backgrounds, social segregation resulted from the broader context of urban community reform in Beijing (Gu et al., 2006). However, a more complex migration process can be observed in the capital city, where not only rural migrants became new citizens (Wang & Zou, 1999), but also experts were strategically brought in and provided with relatively high-quality living environments during the 1990s.

During the last decade of the 20th century, a significantly higher diversity of home layouts emerged due to a more dynamic urban population on the demand side and the introduction of non-state institutional construction and design participants on the supply side. A cultural movement within individual households triggered a new willingness to adopt different ways of living, made possible by advancements in and the popularization of domestic technology. Kitchens and bathrooms, characterized by a high concentration of home appliances, significantly influence the everyday lifestyle of families (Vanek, 1978); kitchens, in particular, due to their spatial relationship to other rooms, foster integration and socialization within the housing (Charytonowicz & Latala, 2011). During the 1990s in Beijing, the number and types of household appliances per family increased rapidly (Beijing Statistical Yearbook, 1999). This surge was aligned with the electrification efforts initiated by the Chinese government, beginning with pilot projects in 109 counties in the mid-1980s and formally launching in 1991 (He, 2019). The introduction and popularization of household appliances in kitchens and bathrooms (Fig. 13c) also potentially signify a shift towards a modernized lifestyle, marking a departure from the Danwei lifestyle. The influence of Western lifestyles was introduced by mass media, where television plays a growing role in family entertainment, and by introducing foreign investment in the Chinese real estate market. Furthermore, this transformation is evident in the spatial organization of rooms within homes in Beijing and influenced behaviors related to food storage, grocery shopping, laundry practices, and leisure activities.

In the era of subsidized housing, customizing interior design to individual preferences was not a significant consideration. With the shift towards market-oriented housing, the significance of housing design, particularly room layout, has grown, potentially influencing the purchasing decisions of homebuyers (Gao et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the apartment’s ___location, floor, and orientation continue to play a pivotal role in the home purchasing process for Chinese households (Jiang & Chen, 2016). This transition also provides more opportunities for the individual living culture to be reflected and expressed through the physical environment of home interiors.

Emerging interior design for urban homes

Floor plans of the 2000s (Fig. 14a–c) and 2010s (Fig. 14d–f) demonstrate a greater diversity in design choices and a reduced level of standardization in visual configurations generated by the layout, in comparison with the unified interior layouts prevalent in the 1970s and 1980s. Furthermore, the weaker correlation between domestic functions during these periods suggests a higher degree of customization and individual preferences in interior design (Appendix 3). The transition from a centrally controlled housing system to a market-oriented one has allowed for more varied design expressions and a greater emphasis on individuality and personalization.

a–c 2000s layouts with heatmap visualizations exhibit a relatively more centralized distribution, with bedrooms arranged in a more compact manner. d–f 2010s layouts with heatmap visualizations highlight areas of interest as transition spaces rather than specific rooms, showing a trend toward more scattered distribution of bedrooms in the floorplan design.

Based on the study period with the smallest sample size, the 1970s (comprising 80 apartments), a random sample of 80 apartments from the each of the 5 study periods was selected. These samples form a dataset for calculating the mean isovist values for each year between 1970 and 2020. The aim is to obtain the mean isovist intensity for each year. Based on the p-values and R-squared values, the primary domestic focus functions in studying the distribution of isovist intensity for homes in Beijing are the living room and dining room. At the same time, the kitchen and bathroom are considered secondary functions. The results in Fig. 15 examine the correlation between the year of construction and the mean IIS for each domestic function to get a development trend for different functions by controlling the square footage of the apartments in Beijing. However, regarding the transformation pattern, both square footage and the price of apartments display significance for certain domestic functions in the correlation between IIS and time (Appendix 4).

Correlation between the year of construction and mean IIS per year for small and large apartments in Beijing, by room type: living room (a), dining room (b), kitchen (c), and bathroom (d), since 1970. a The dining room in small apartments shows an increasing IIS, whereas a decreasing IIS is observed in large apartment dining rooms. b The kitchen in large apartments shows a slight increase in IIS. c A sharp drop in IIS is observed in the bathroom of small apartments. d An increase in IIS is observed in the balcony of small apartments. Please find Appendix 4 for the complete correlation illustration between the year of construction and mean IIS per year controlled by price and functions of bedroom and balcony.

The selection of living rooms, dining rooms, and kitchens as focal points for this section is informed by their significant role in developing IIS trends since 1970 (Table 1). An analysis of design trends in smaller apartments (less than 59 m²) indicates a notable temporal correlation: more recent constructions typically demonstrate a reduction in the visual accessibility of living rooms while concurrently exhibiting enhanced visual accessibility in dining rooms. This pattern is evident in small to median-sized apartments (59–76 m²), where dining rooms and kitchens display increased visual accessibility. Larger apartments (more than 96 m²), generally show a less obvious development trend mainly caused by less restriction by the room layout design.

Living room

Regression analysis indicates a positive correlation between the year of construction and the IIS in living rooms—for small apartments, it has a p-value of 0.000. Figure 15a illustrates a contrasting trend in the visual accessibility of living rooms between small and large apartments. While there is a slight decrease in visual accessibility for living rooms in small apartments, visual accessibility in living rooms for large apartments is on the rise. However, given the earlier argument regarding the mixed living and dining function in small apartments, the differences in the design of living rooms and dining rooms between large and small apartments suggest that the arrangement of domestic functions may be influenced by the apartment size.

During the Danwei period, living rooms were often omitted from the interior design, reflecting a perception that they were not essential for domestic life. In contrast, bedrooms were designed to facilitate a higher activity level, fulfilling more than its primary function (sleeping space). This led to a prevalent mixed-use concept in dwellings before the reform period. However, the contemporary trend of frequently including beds in Beijing’s living rooms reflects a continuation of private living culture, a practice less likely to be observed in Shanghai homes (Yao, 2024). This suggests an internal cause for the potential decrease in the visual accessibility of living rooms.

Dining room

The p-value indicates a significant overall correlation between the IIS in the dining room and the age of the homes in Beijing, with an increasing IIS in the dining rooms of newer-built apartments over time. These dining rooms are designed to be more visually integrated, potentially encouraging household social encounters. Considering the historical context during the work-unit system period, where public dining halls were commonly built within a Danwei, there was less demand for private dining spaces within individual homes. However, from a cultural perspective, the dining space in Chinese homes has traditionally played a vital role in building social networks and creating a sense of belonging (Cheung, 2001; Ma, 2015). The growing visual accessibility of the kitchen, which brings family gatherings, manifests this privatization of domestic space in the sense of culture. The dining hall, however, was the production of collective living supported by Danwei; it can still be seen as how space responds to culture, which is later reflected through the home interior. A general developing trend happened inside an individual’s home, suggesting the broader socio-political landscape at the individual level and within the private sphere after the Danwei period. Although local living culture remains profoundly influential on the space around individuals, it creates the space for everyday life.

Kitchen

Regarding the kitchens, middle-size apartments (59–96 m2) in Beijing show a growing trend in the IIS, whereas smaller apartments show a more significant pattern. During the work-unit system period, the kitchen was officially included in the public dining hall; its cultural significance remained evident from the arraignment of the physical environment; its unique cultural significance was embedded in daily routine. Technological limitations and public dining culture meant it was not considered an essential domestic function within the home. However, cooking as part of the dining process held a profound cultural importance for Chinese families, a tradition also prevalent during the Danwei period. An alternative cooking place was developed spontaneously by families living in a typical “Tong Zi Lou” (tube-shaped apartment) designed to accommodate a new immigrant population to Beijing during the 1980s and 1990s. This cultural practice of cooking in the hallway emerged from the collective lifestyle, transforming the semi-public hallway into a significant space for social interactions. This characteristic of cooking space during the Danwei period intensified the idea that dining is critical for the Chinese household that forms social spaces. It could influence the increasing visibility and openness of kitchens in Beijing’s contemporary apartments, encouraging the integration of kitchens and dining rooms to accommodate social activities within homes.

On the other hand, the growth of IIS could be attributed to the introduction of Western-style open kitchens. The Chinese-style kitchen, deeply influenced by cultural practices and cooking styles, tends to be more isolated. This difference in cooking style, rooted in cultural practices, may be one of the critical reasons for the divergence between Chinese and Western kitchen arrangements. Where separated or integrated kitchens appear. In middle or smaller size apartments, the signal regarding the kitchen could be more assertive, suggesting the potential absence of a separate kitchen space in such units, where a more flexible space arrangement emerges compared with large or small apartments there, where the kitchen has enough space to be separated or the space is too limited for alternative design for arranging kitchen and living-dining space.

From privatization of housing to individual domestic culture

Despite the relative lack of extensive data for larger apartments over time, the study suggests a discernible shift in the design of small apartments, influenced by political and lifestyle factors (Table 1). Small apartments built in different periods in Beijing exhibit a decreasing use of the living room as a gathering space and an increase in the role of the dining room as a social hub for households by considering modern apartments as a non-local housing type in Beijing, but a “living machine” driven by functionalism contemporarily (Corbusier, 2013). The way living space within the home evolves exhibits a process of indigenizing urban apartments in China. The shift in functions, from external to internal home spaces—encompassing dining, cooking, socializing, and entertaining—aligns with housing modernization, underpinned by broader urban and social developments. Consequently, housing, as a material culture (Miller, 2021), becomes pivotal in exhibiting local identities, even in contemporary apartment-style living.

During the reform period, the internal dynamics of family living also changed, and this shift has further intensified through the housing movement in Beijing. Urban housing communities in China started to adopt “foreign inspired” architectural designs and domestic lifestyles, resonating with the aspirations of the rapidly growing middle class (Pow & Kong, 2007). Furthermore, the domestic sphere has played a crucial role in transforming China’s urban consumption landscape (Davis, 2000). Appliances such as TVs, washing machines, and refrigerators have become commonplace in homes, mirroring the trend of home privatization. This dual privatization process, both at social and individual levels, has contributed to transforming urban Chinese life from a housing perspective. Here, housing interiors have functioned not merely as a supportive element during this transition but as an active ___domain where individuals can express their cultural identities, adapting to broader social and technological changes.

Conclusion

This paper investigates how urban apartment layouts in Beijing responded to major urban policies, particularly before and after housing reform, potentially triggering a transformed interplay of function and social activities within and outside urban homes. These findings highlight the profound impact of urban policies on domestic life, shaping cultural norms and behaviors within the home. The study establishes a relationship between apartment size, construction year, and spatial configuration, demonstrating how macro-level policies influence individual living environments. This underscores the importance of interior spaces in understanding urban social and political movements.

Future research should explore diverse regional contexts and integrate indoor/outdoor imagery datasets, including private and public sources, for a more holistic view of urban living. The dynamic interaction between individuals and micro-scale urban spaces, such as home interiors, occurring at shorter time scales, presents complexities involving both physiological and psychological factors. Future studies could benefit from a high-resolution research paradigm that fosters a closer examination of the relationship between individuals and macro-level urban space. Investigating the impact of evolving household objects on interior design is also crucial for urban studies, promoting a more interdisciplinary approach.

While this research provides valuable insights, it also has limitations. The home space reflects local identity, and our findings may have been influenced by the climate, demographics, socio-economic factors, and historical factors specific to Beijing. These findings could vary across different regions in China and globally. Additionally, using commercial platform data for imagery analysis may introduce biases. Future work could benchmark findings against alternative machine learning datasets, such as RPLAN and CubiCasa5K.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the “Beijing’s Urbanization Reflected in Apartment Layouts” repository, that can be accessed at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/GVIRPX.

Notes

References

Batty M (2001) Exploring isovist fields: space and shape in architectural and urban morphology. Environ Plan B Plan Des 28(1):123–150

Beijing Statistical Yearbook (1999, 2020, 2023)

Benedikt ML (1979) To take hold of space: isovists and isovist fields. Environ Plan B Plan Des 6(1):47–65

Benedikt ML, McElhinney S (2019) Isovists and the metrics of architectural space. Proceedings 107th ACSA Annual Meeting; Ficca, J, Kulper, A, eds

Bjorklund EM (1986) The Danwei: socio-spatial characteristics of work units in China’s urban society. Econ Geogr 62(1):19–29

Bonino M, De Pieri F (2015) Beijing danwei: industrial heritage in the contemporary city. Jovis

Braaksma JP, Cook WJ (1980) Human orientation in transportation terminals. Transport Eng J ASCE 106(2):189–203

Bradski G (2000) The openCV library. Dr Dobb’s J Softw Tools Prof Progr 25(11):120–123

Bray D (2005) Social space and governance in urban China: The danwei system from origins to reform. Stanford University Press

Brooker G, Stone S (2009) Basics Interior Architecture 04: Elements/Objects (Vol 4). AVA Publishing

Canny J (1986) A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, (6), 679–698

Carta S (2021) Self-Organizing Floor Plans. Harvard Data Science Review, 3. https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.e5f9a0c7

Charytonowicz J, Latala D (2011) Evolution of domestic kitchen. International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction.Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg

Cheung SY (2001) The Importance of Food in Understanding Chinese Culture. In E Tan (ed), Food and Foodways in Asia: Resource, Tradition, and Cooking (pp 9–18). London: Routledge

Corbusier L (2013) Towards a new architecture. Courier Corporation

Davis D (ed) (2000) The consumer revolution in urban China (Vol 22). University of California Press

Douglas O, Russell P, Scott M (2019) Positive perceptions of green and open space as predictors of neighbourhood quality of life: implications for urban planning across the city region. J Environ Plan Manag 62(4):626–646

Duda RO, Hart PE (1972) Use of the Hough transformation to detect lines and curves in pictures. Commun ACM 15(1):11–15

Gao X, Asami Y, Zhou Y, Ishikawa T (2013) Preferences for floor plans of medium-sized apartments: a survey analysis in Beijing, China. Hous Stud 28(3):429–452

Gong P, Liang S, Carlton EJ, Jiang Q, Wu J, Wang L, Remais JV (2012) Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet 379(9818):843–852

Gu C, Chan RC, Liu J, Kesteloot C (2006) Beijing’s socio-spatial restructuring: Immigration and social transformation in the epoch of national economic reformation. Prog Plan 66(4):249–310

Hamnett C (2020) Is Chinese urbanisation unique? Urban Stud 57(3):690–700

He X (2019) China’s electrification and rural labor: analysis with fuzzy regression discontinuity. Energy Econ 81:650–660

Hieu PQ, Thuy NTB (2024) Data-Driven Interior Plan Generation for Residential Buildings in Vietnam. In: Das, S, Saha, S, Coello Coello, CA, Bansal, JC (eds) Advances in Data-Driven Computing and Intelligent Systems. ADCIS 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 893, Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-9518-9_5

Hillier B, Hanson J, Graham H (1987) Ideas are in things: an application of the space syntax method to discovering house genotypes. Environ Plan B Plan Des 14(4):363–385

Huang Y (2004) Housing markets, government behaviors, and housing choice: a case study of three cities in China. Environ Plan A 36(1):45–68

Jiang H, Chen S (2016) Dwelling unit choice in a condominium complex: analysis of willingness to pay and preference heterogeneity. Urban Stud 53(11):2273–2292

Jiang D, Chen JJ, Isaac D (1998) The effect of foreign investment on the real estate industry in China. Urban Studies, 35(11):2101–2110

Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Qiu J (2023) YOLO by Ultralytics (Version 8.0.0) [Computer software]. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics

Josselyn IM (1953) The family as a psychological unit. Soc Casework 34(8):336–343

Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, Robinson JP, Tsang AM, Switzer P, Engelmann WH (2001) The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 11(3):231–252

Kwon SJ, Sailer K (2015) Seeing and being seen inside a museum and a department store. A comparison study in visibility and co-presence patterns. In Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium (Vol. 10, p. 24). Space Syntax Laboratory, The Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London

Li S (2000) Housing consumption in urban China: a comparative study of Beijing and Guangzhou. Environ Plan A 32(6):1115–1134

Li R, Huang H (2020) Visual Access Formed by Architecture and its Influence on Visitors’ Spatial Exploration in a Museum. Interdisciplinary Journal of Signage and Wayfinding, 4(1)

Li Z, Gou F (2020) Residential segregation of rural migrants in post-reform urban China. In Handbook of Urban Segregation. Edward Elgar Publishing

Lin H (2014) Evolving Danwei housing: an alternative way to develop former public housing in Shenzhen, China

Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, … Zitnick CL (2014) Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Computer Vision-ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13 (pp 740–755). Springer International Publishing

Lu D (2003) Building the Chinese work unit: Modernity, scarcity, and space, 1949–2000. University of California, Berkeley

Ma G (2015) Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese society. J Ethn Foods 2(4):195–199

Ma LJ, Xiang B (1998) Native place, migration and the emergence of peasant enclaves in Beijing. China Q 155:546–581

Merrell P, Schkufza E, Koltun V (2010) Computer-generated residential building layouts. ACM SIGGRApH Asia 2010 papers. 2010:1–12

Miller, D (Ed) (2021) Home possessions: material culture behind closed doors. Routledge

Miranda AS et al. (2021) Desirable streets: Using deviations in pedestrian trajectories to measure the value of the built environment. Comput Environ Urban Syst 86:101563

Mitton M, Nystuen C (2021) Residential interior design: a guide to planning spaces. John Wiley & Sons

Nasar JL (1990) The evaluative image of the city. J Am Plan Assoc 56(1):41–53

Ostwald MJ, Dawes MJ (2013) Using isovists to analyse architecture: methodological considerations and new approaches. Int J Constr Environ 3(1):85–106

Page L, Brin S, Motwani R, Winograd T (1999) The PageRank citation ranking: Bringing order to the web. Stanford Infolab

Palmquist RB (1984) Estimating the Demand for the Characteristics of Housing. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 394–404

Pan L, Zhu M, Lang N, Huo T (2020) What is the amount of China’s building floor space from 1996 to 2014? Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(16):5967

Pow C-P, Kong L (2007) Marketing the Chinese dream home: gated communities and representations of the good life in (post-) socialist Shanghai. Urban Geogr 28(2):129

Ren H, Folmer H (2022) New housing construction and market signals in urban China: a tale of 35 metropolitan areas. J Hous Built Environ 37(4):2115–2137

Rodrigues RC, Duarte RB (2022) Generating floor plans with deep learning: a cross-validation assessment over different dataset sizes. Int J Archit Comput 20(3):630–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/14780771221120842

Sailer K, Koutsolampros P, Pachilova R (2021) Differential perceptions of teamwork, focused work and perceived productivity as an effect of desk characteristics within a workplace layout. PloS One 16(4):e0250058

Saraiva S, Serra M, & Furtado G (2019) Rethinking contemporary domestic space organization. Proceedings of the 12th Space Syntax Symposium

Scott JW (1979) The history of the family as an affective unit. Soc Hist 4(3):509–516

Simonyan K, Zisserman A (2014) Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556

Sirmans GS et al. (2006) The value of housing characteristics: a meta-analysis. J Real Estate Financ Econ 33(3):215

Song S, Zhang KH (2002) Urbanisation and city size distribution in China. Urban Stud 39(12):2317–2327

Turner A et al. (2001) From isovists to visibility graphs: a methodology for the analysis of architectural space. Environ Plan B Plan Des 28(1):103–121

Vanek J (1978) Household technology and social status: Rising living standards and status and residence differences in housework. Technol Cult 19(3):361–375

Wang F, Zuo X (1999) Inside China’s cities: Institutional barriers and opportunities for urban migrants. Am Econ Rev 89(2):276–280

Whyte WH (1980) The social life of small urban spaces

Wiener JM, Franz G, Rossmanith N, Reichelt A, Mallot HA, Bülthoff HH (2007) Isovist analysis captures properties of space relevant for locomotion and experience. Perception 36(7):1066–1083

Wu F (1998) The new structure of building provision and the transformation of the urban landscape in metropolitan Guangzhou, China. Urban Stud 35(2):259–283

Wu F (2018) Housing privatization and the return of the state: changing governance in China. Urban Geogr 39(8):1177–1194

Wu C (2020) Machine learning in housing design: exploration of generative adversarial network in site plan/floorplan generation. Dissertation. Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Wu F, Xu J, Yeh AG-O (2006) Urban development in post-reform China: State, market, and space. Routledge

Wu W, Fu XM, Tang R, Wang Y, Qi YH, Liu L (2019) Data-driven interior plan generation for residential buildings. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG), 38(6):1–12

Yao S, Luo D, Wang J (2014) Housing development and urbanisation in China. World Econ 37(3):481–500

Yao Y (2024) Spatial Analysis Method for Housing Interior Utilizing Image Big Data. Tsinghua University, Beijing

Yeh AG-O, Wu F (1996) The new land development process and urban development in Chinese cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res 20(2):330–353

Yeh AG-O, Wu F (1999) The transformation of the urban planning system in China from a centrally-planned to transitional economy. Prog Plan 51(3):167–252

Zhang T (2000) Land market forces and government’s role in sprawl: the case of China. Cities 17(2):123–135

Zhang H (2022) Consumer Cities: The Role of Housing Variety

Zhang S, Lee D, Singh PV, Srinivasan K (2022) What makes a good image? Airbnb demand analytics leveraging interpretable image features. Manag Sci 68(8):5644–5666

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. AK: Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. MM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. FD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. LS: Supervision, Funding. LS: Supervision, Funding. CR: Funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Fábio Duarte was a member of the Editorial Board of this journal at the time of acceptance for publication. The manuscript was assessed in line with the journal’s standard editorial processes, including its policy on competing interests. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not applicable for this study because it does not involve human participants or their data.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not applicable for this study because it does not involve human participants or their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Y., Kumar, A., Mazzarello, M. et al. Beijing’s urbanization reflected in apartment layouts: a computer vision and isovist analysis (1970–2020). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04768-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04768-1