Abstract

Different jurisdictions have different criminal law attitudes towards the illegal use of personal information, i.e., no criminalisation, selective criminalisation based on specific conditions, or overall criminalisation. China should move from the first approach to a new approach. China’s criminal law has adopted a traditional privacy protection strategy focusing on information transfer. The existing crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information is limited to addressing the illegal acquisition and provision of personal information. Nevertheless, it fails to fully consider the core position of the right to use in the full life cycle of the autonomous operation of personal information. By doctrinal analysis, the urgent and precise risk of further damage to citizens’ personal lives, property, and social order contained in illegal use provides a solid basis for criminal law regulation. According to policy analysis, in jurisdictions where information technology such as big data and AI is widely available, for example, China, the illegal use of personal data particularly disrupts the community’s sense of security. Criminal law should expand its scope, but it must justify its reach. On the one hand, by categorizing the illegal use of personal information, a comprehensive judgement can be made about whether to criminalise certain behaviours according to the degree of infringement on personal information autonomy, the harm to other legal interests, and the level of personal danger posed by the perpetrator. On the other hand, the corresponding reasons for exceptional noncriminalisation should be determined in the respective private, personal, and social spheres to achieve a balance between protecting citizens’ autonomy in using personal information and highlighting the value of data circulation. This investigation process and the results can serve as references for member states of the GDPR and other jurisdictions seeking more rigorous protection of personal data in contemporary society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A decade ago, De Hert asserted that the drafted European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)Footnote 1was unwilling to coordinate civil compensation, administrative, and criminal sanctions and that this unwillingness is appalling and indefensible (De Hert 2014). The coordination of different sanctions in the GDPR framework has not been updated. Although criminal sanctions are necessary and feasible within a jurisdiction, they are coordinated with administrative sanctions and civil law sanctions (Dimitrova 2019, 2020; Shutova 2022). The second part of this paper shows that, over the past decade, various jurisdictions have made specific assessments and choices concerning the criminalisation of illegal acts, especially the illegal use of personal data,Footnote 2 with different approaches and to different degrees according to their respective legal systems, criminalisation needs, cultures and theories of personal data protection. The GDPR is retained in domestic law as the UK GDPR is, but the UK independently reviews the framework. The second part analyses how the UK chooses not to directly criminalise the illegal use of personal data, whereas Germany, as a member state of the GDPR, chooses to criminalise it.

In recent years, Chinese scholars have discussed the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information and agreed on the necessity and feasibility of criminalising the illegal use of personal information (Liu 2019; Liu 2020; Liu and Song 2022; Lu and Zhang 2023). However, there are still large differences in the conditions under which the use of personal information is criminalised (whether and how to specify the types of behaviour and determine the degree of illegality of the use of personal information) and the degree of criminalisation (how to determine the legalization of the use of personal information and the range of legal penalties). Therefore, this article aims to conduct a systematic study on the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information by comparing criminalisation models and summarizing key criminalisation issues (Part 3); considering the current situation and trend of China’s personal data legal system, practices, principles, and needs of criminal legislation (Parts 4 and 5); and showing how a specific jurisdiction such as China can improve its criminal protection system concerning personal data (Part 6). This investigation process and the results can be useful to member states of the GDPR and other jurisdictions seeking intensified protection of personal data in contemporary society.

Key definitions and theoretical context

Key definitions

Before beginning a formal study on the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information, it is necessary to define the illegal use of personal information. The definition of personal data can differ across jurisdictions and is not the focus of this study. For the purposes of this article, it is sufficient to cite the definition of personal information specified in current Chinese law. Article 4(1) of the 2021 Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) stipulates that personal information is information related to identified or identifiable natural persons recorded electronically or by other means, excluding information that has been anonymized.

Thus, we should seek a technical and legal definition of the possible uses of personal data. China’s PIPL does not define the use of personal information but only lists it as one of the ways personal information is processed in Article 4, paragraph 2. Article 3.6 of the 2019 departmental normative standard, ‘Internet Personal Information Security Protection Guide’, issued by the Network Security Bureau of the Ministry of Public Security jointly with the Beijing Network Industry Association and the Third Research Institute of the Ministry of Public Security, defines the use of personal information as any operation involving personal data by automated or manual means. These operations include recording, organizing, storing, adapting, retrieving, consulting, disclosing, disseminating, providing, adjusting, combining, restricting, deleting, etc.

However, this broad definition has been difficult to apply after the 2021 PIPL (Article 4, paragraph 2), which distinguishes the use of personal information from the collection, storage, processing, provision, disclosure, and deletion of personal information and lists them all as specific processing methods. We therefore follow the more authoritative rule of the 2021 PIPL. According to this rule, the use is different from the provision, such as selling. Correspondingly, the Explanations of Common Terms in the Data Field (Second batch) published in 2025 by the Chinese National Bureau of Data state the following: “Generally, the right of use is the right of the right holder to use the data for internal use without providing the data to the outside world.” Specifically, Article 7 of the national standard ‘Personal Information Security Code’ (GB/T 35273–2020) lists the use scenarios of personal information, including the display of personal information, the use of user portraits, the use of personalized displays, the convergence of personal information collected for different business purposes, the use of automatic decision-making mechanisms of information systems, etc. as specific types of personal information use. However, from this list, it is still difficult to extract a unified and clear definition.

The definition of ‘personal information’ in the Personal Information Protection Act can help us clarify the definition of the use of personal information to a certain extent. Article 4(1) of the PIPL stipulates that personal information is related to identified or identifiable natural persons. Therefore, the ‘use of personal information’ as the object of this study refers to the behaviour of directly exerting the effects of various information related to identified or identifiable natural persons, which directly determines the subject, object, time, method, occasion, and purpose of exerting the effects. It refers to the personal information controller/processor’s management and operation of personal information after collection, processing, polymerization, and analysis. Therefore, it has a particular purpose for fulfilling a particular function or service, particularly to optimize production and operation, form derivative data, etc. For example, creating a personal portrait or making a decision on the basis solely of the automated processing of personal information, which may have legal or other significant effects on the information subject, is a typical use of personal information (Fan 2023). Under normal circumstances, sales, exchange, disclosure, retrieval, consultation, disclosure, dissemination, other providing behaviours, adaptation or change, and other processing behaviours cannot directly play the role of personal information at a specific time, way, occasion and purpose but can provide conditions for the direct play of personal information, so they do not constitute the use of personal information.

Third, which of these possible uses of personal data can be considered illegal? The illegal use of personal information refers to directly exerting the effects of personal information beyond a reasonable purpose, scope, extent, and manner. It involves the use of personal data in a way that violates the data protection rules. The illegal use of personal information usually takes three objective forms: unauthorized use, false use, and forgery and alteration (Lu and Zhang 2023). Notably, these three forms of illegal use correspond to Prosser’s summarization of privacy intrusion (Prosser 1960). Prosser lists four kinds of privacy intrusion: intrusion upon another’s seclusion or into another’s private affairs, public disclosure of another’s embarrassing private facts, publicity that represents another in a false light, and appropriation of another’s name or likeness for one’s own advantage. The first type of intrusion is pure intrusion, not the direct use of privacy. The latter three kinds of intrusion are not simple intrusions but further use privacy, and they correspond to and thus help us understand the features of the three forms of the illegal use of personal data. The public disclosure to embarrass is an unauthorized use; the false use of personal data can place others in a false light in the public eye, as can the publicity of others’ privacy, and the appropriation of others’ names or likeness, although not necessarily in the form of forgery and alteration, is usually for one’s own advantage, as is forgery and the alteration of others’ personal data.

The first type of behaviour is the false use of others’ personal data, which refers to violating the autonomy of using personal data and engaging in activities in the name of the data subject. At this time, the identity data of others are used mainly to attribute the effect of the activity to the data subject. Such identity data theft may cause others to suffer the consequences of failure or illegal activities (Ribet 2023). Examples are using others’ identity data to register a company so that others bear the risk of business failure and misusing other people’s data for false tax returns, illegal marketing or telecommunications network fraud activities so that the data subject or third party bears the risk of illegal and criminal behaviour. Another behavioural effect of identity data theft is to directly infringe on the interests of the data subject, such as fraudulently using other people’s identity data to vote or apply.

The second type is the unauthorized use of others’ personal data in activities undertaken in one’s name. For example, other people’s data can be used for a variety of purposes, such as personalized display, marketing, illegal automated decision-making, and personal portraits. At this time, the effect of the activity belongs to the actors, but they arbitrarily use others’ personal data to produce the desired effect.

The third type of behaviour involves falsifying or transforming other people’s personal data into data in other scenarios. An example is when the biometric data of others are spliced and transferred to obscene videos or spliced and transferred to records of indecent or illegal events such as prostitution or drug use. At this time, actors are still using others’ personal data without authorization, but they have forged or altered others’ personal data to produce the desired results.

These three types of behaviour make the illegal use of personal data typed and clear, more in line with the principle of nullum crimen sine lege, to meet the predictability needs of citizens. As Article 3 of the Chinese Criminal Law stipulates, “If an act is expressly prescribed as a crime by the law, it shall be convicted and sentenced by the law; if the law does not expressly provide that the act is a crime, it shall not be convicted and sentenced.” Under the basic principle, the legal nature of crime and the clarity of its constituent elements are inseparable (Liu 2010; Xiao 2012). The criminalisation of the illegal use of personal data should determine clear behaviour types of criminalisation, which is a technical requirement of criminal legislation based on the first principle of criminal law (nullum crimen sine lege).

Criminalisation context

The illegal use of personal data does not necessarily entail the use of personal data for criminal law purposes. For example, the use of personal data for longer than necessary (establishing the duration of use is a traditional data protection requirement or condition) is not necessarily a use that qualifies as criminal for criminal law purposes. Violating the rules of data protection processing does not itself constitute a crime.

Violating the rules of data use is necessarily a tort. This tort harms the use autonomy of the data subject (the ability to independently decide under what circumstances to use their personal information for what purpose, way and degree) and probably other legal interests. This article explains how examining violations of use autonomy helps explain the application of criminal law. Again, using personal data longer than required may violate privacy and harm the individual; however, does it justify the application of criminal law? There needs to be a distinction between torts and criminal law: something can be criminalised and not dealt with as a tort, and the reverse can also be true. Therefore, the relevance of discussing torts needs to be explained.

For the use of personal data to be criminalised, it first needs to be a tort, violating civil law and data protection rules. Only violations of civil law and data law can qualify as criminal behaviour. A behaviour that is legal according to civil law and data law cannot be criminal behaviour. Civil law and data law are preexisting laws of criminal law, and criminal law safeguards the enforcement of preexisting laws such as civil law and data law (Sun 2012; Wang 2015). Therefore, if there is no behaviour violating preexisting laws such as civil law and data law, criminal law does not need to intervene. In contrast, examining violations of civil law and data protection rules can preliminarily justify the use of criminal law (see the “legal order” in Part 4).

However, even if doctrinally, there is behaviour violating preexisting laws such as civil law and data law, criminal law is not necessarily applied. The intervention of criminal law as a last resort needs rationales other than that the behaviour infringes on a new theoretically recognizable interest that can be and has been recognized in preexisting legal order or that the new interest involves other interests traditionally recognized by criminal law (see Part 4). The additional rationales come mainly from criminal policy (Ma 2007), which can be analysed from the mature framework (see Part 5) in the Model Penal Code developed by the American Law Institute. The code has been translated and advocated by Chinese scholars (American Law Institute 2005). The rationales also concern the legislative technical feasibility (Zhao 2017) of prescribing illegal uses’ respective illegality extent, exceptional justifications for using personal data in criminal law and proportionate penalty ranges (see Part 6). These rationales (and limitations) of criminalisation as a context can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a jurisdiction’s approach.

Investigating the criminalisation of illegal use of personal data

Different jurisdictions have adopted different modes to address the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information, which suggests that this issue cannot be generalized and needs to be discussed based on the principle of criminalisation while considering the relevant situation of the legal system of personal data protection in specific jurisdictions.

All countries seem to have partially ‘criminalised’ the illegal use of personal information (and a general principle governing the use of personal information, although not necessarily in a criminal sense). In the case of the Chinese legal system and criminal law, only criminal law can prescribe offences; other laws can prescribe civil torts only such as the Civil Code does or administrative violations such as the PIPL does. Therefore, criminalisation refers to behaviour as a criminal offence with penal treatment in criminal law rather than treating the behaviour with civil compensation or administrative punishments.

No direct criminalisation

The first model does not directly criminalise the illegal use of personal data. China’s criminal law (Article 253) was amended in 2015 to stipulate the crime of “infringing on citizens’ personal information”, and it seems that all or at least most of the types of acts infringing on citizens’ personal information can be covered by this crime. However, this crime covers only the illegal acquisition, illegal sale, and provision of personal information and does not address other violations of personal information, such as illegal use. Compared with the relatively complete provisions on the rights of individuals in the processing of personal information in the PIPL issued in 2021, criminal law has not expanded the scope of the crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information.

It is difficult to obtain appropriate responses to existing criminal law norms. In the face of the possible criminalisation demand for the illegal use of personal information in criminal policy, the first issue to examine is whether judicial practice can be effective by adequate criminal law interpretation based on existing criminal law norms. Scholars have proposed that the illegal use of personal information after illegal acquisition can be punished under the provisions of Article 253, paragraph 3, of the Criminal Law on the illegal acquisition of personal information (Liu and Song 2022). At this stage, it is not possible to directly crack down on the illegal use of personal information; rather, we can address only on the illegal acquisition of upstream behaviour and then regard this behaviour as a serious circumstance.

However, this line of thinking cannot combat the illegal use of legally obtained personal information. To this end, some scholars have proposed expanding the interpretation of illegal access: the illegal use and processing of facial recognition information can be included in the category of ‘illegal’ access under the crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information (Li 2022). In this case, even if the method of acquisition appears to be legal, it can still be considered illegal as long as it serves the purpose of illegal use at the time of acquisition. However, this interpretation faces the problem of how to prove an illegal use purpose when the actor obtains the information; it cannot address the situation in which there is no illegal use purpose when the actor obtains it or when the illegal use purpose occurs after the acquisition. The use of personal information to commit crimes can be addressed according to the crime committed. However, this approach can address only crimes that have been verified after the fact, such as dissemination after the use of other people’s facial information for obscene video synthesis, but synthesis cannot be prevented in advance. Moreover, cases in which personal information is used only to carry out illegal rather than criminal activities, no matter how serious the other circumstances are, cannot be treated as crimes.

The illegal use of citizens’ personal information is independent and cannot be included in the current crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information through interpretation. Moreover, owing to the different protectable interests of the law, the illegal use of citizens’ personal information cannot be covered by other crimes in criminal law. Therefore, although from a practical point of view, there are two ways to criminalise the illegal use of citizens’ personal information (judicial interpretation and criminal law amendment), from a reasonable point of view, to maintain the principle of nulla poena sine lege, it is more appropriate to criminalise the illegal use of citizens’ personal information through criminal law amendment (Liu 2019).

In this context, Chinese scholars have repeatedly proposed criminalising the illegal use of personal information (Liu 2019); however, whether this proposal should be implemented in the future amendment of criminal law, as well as the specific implementation plan, still needs to be fully discussed by comparing law and theory.

Let us first consider the UK. The UK, as a GDPR-related jurisdiction, adopts the same model of no direct criminalisation of illegal use of personal data as current China does, so it may be insightful to examine how and why it does so. The UK’s Data Protection Act 2018 harmonizes a set of principles for data protection and a set of rights for data subjects; however, among the crimes concerning personal data, only illegal acquisition and distribution, such as the processing of personal data (Article 170), reidentification of deidentified personal data (articles 171–172), and alteration of personal data to prevent disclosure to the data subject (article 173), are covered. The reasonable range of criminalisation of infringement of personal data could be considered comprehensively when the rights of personal data and the corresponding crimes of infringing on personal data rights are stipulated at the same time. However, although the United Kingdom has provided comprehensive personal data rights, it has provided only partial criminal law protection for these rights, especially since the illegal use of personal data has not been criminally punished. It seems that British lawmakers believe that the illegal use of personal data is not necessarily criminalised, but the specific reasons for this policy are still unknown.

The unlawful acquisition and publication offences under Section 170 above are old offences inherited from Section 55 of the Personal Data Protection Act 1998, whereas the offences under Sections 171 and 173 are new offences under the Data Protection Act 2018. These two types of new crimes are not stipulated in China’s criminal law, which shows that the scope of personal data protection in British criminal law is broader than that in China. The problem, however, is that the illegal use of personal data is still not covered by UK criminal law, in contrast to the crackdown on the two types of acts provided in Articles 171 and 173. This neglect of other acts such as illegal use of personal data seems to be ‘arbitrary’, and the legislation does not present a consistent rationale for distinguishing between ‘do criminalise’ and ‘do not criminalise’. The explanatory note to the Data Protection Act of 2018 mentions that the act replicates many criminal offences in the 1998 Act and has been amended in line with changes to the legal framework by the GDPR, introducing a small number of new offences to address emerging threats.Footnote 3 For example, the Section 171 offence responds to concerns about the security of deidentified data in online files. The UK’s National Guardian for Health and Care Data, in its Data Security, Consent and Opt-out Review, called on the government to introduce stricter sanctions to protect unidentified patient data. With the development of big data-driven biomedical research, there are increasing calls for criminal sanctions against the illegal reidentification of anonymized data (Phillips et al. 2017). The integration of law and information technology constitutes the guarantee of criminal law to deter attempts to revert to technologically deidentified personal data (Lin 2019).

However, the illegal use of personal data did not receive sufficient attention in the UK legislation; if the reason is simply that no one raised the threat of the illegal use of personal data during the legislation process, then did anything change between 2018 and the present? Unfortunately, no useful material has been found. However, this finding reminds us that there may be no strong policy reasons to specify the illegal use of personal data in the UK as an offence. Alternatively, from the perspective of legal techniques, some serious cases of the illegal use of personal data can be addressed by other existing offences, such as conspiracies to defraud or unauthorized access to computer systems. However, these reactions are ad hoc and piecemeal rather than coherent in capturing the breadth of illegal use activities or their extent of harm.

In summary, the current mode of treating the illegal use of personal information in China and the United Kingdom is a nonpenal governance mode that involves only civil compensation and administrative punishment. However, it is still necessary to discuss the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information. Although the GDPR does not harmonize criminal offences of illegal processing of personal data in Europe, relevant jurisdictions such as the UK and Germany (see ‘overall criminalisation’ below) have endeavoured to do so but in different models. The reasons for a given jurisdiction’s model are not obvious because of either the lack of relevant materials or the lack of rationality of the model itself. However, for China, we have enough information to choose a model, and we can rationally analyse the criminalisation issue being debated. The analysis process and the results can be valuable contributions to a topic that is often difficult to discuss.

In a 2020 official note on the draft of the Personal Information Protection Law, China stated that the ‘illegal collection and use of personal information not only harm the vital interests of the people but also endanger the security of transactions, disrupt market competition, and disrupt the order of cyberspace. Therefore, special laws should be formulated and promulgated to regulate personal information processing activities with strict systems, strict standards, and strict responsibilities and implement the legal obligations and responsibilities of personal information processors such as enterprises and organizations to maintain a sound environment in cyberspace.’ Here, the illegal collection of personal information and the illegal use of personal information are juxtaposed, but current criminal law makes a clear distinction between them. According to current criminal law, only when illegally used information is illegally obtained does it qualify as a crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information and is subject to punishment of the type of behaviour of illegally obtaining personal information towards collaterally cracking down on subsequent illegal use. In 2017, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate interpreted the 2015 amended Article 253 of criminal law and stipulated in Article 6 of the Interpretation of Several Issues concerning the Application of Law to Criminal Cases involving infringement of Citizens’ Personal Information that illegal purchase and acceptance of ordinary personal information for lawful business activities, under one of the following circumstances, shall be identified as ‘serious circumstances’ stipulated in Article 253 of the Criminal Law: Making a profit of more than 50,000 yuan by using citizens’ personal information that was illegally purchased or obtained. If the illegal use of illegally obtained personal information fails to meet the above profit standard, the provision of criminal law on illegal access to personal information should not be applied. Moreover, when illegally used personal information is obtained legally, it is more difficult to apply provisions for the crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information to regulate the illegal use of personal information.

Selective criminalisation

The second model selectively criminalises the illegal use of personal information. The legislation of some jurisdictions, such as the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, supports the criminalisation of the illegal use of citizens’ personal information (Liu 2019), but there are differences in the criminalisation conditions. The first condition is the violation of the notification or request of the competent authority for the protection of personal data concerning the reasonable use of personal information. Section 50 of the Hong Kong Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance applies to an enforcement notice: if, after completing an investigation, the Commissioner believes that the data user concerned is or has contravened a requirement under this Ordinance, the Commissioner may serve a written notice on the data user directing the data user to rectify the contravention and, if appropriate, to prevent the recurrence of the contravention. Section 50A applies to an offence related to an enforcement notice: a data user who does not comply with an enforcement notice commits an offence. On first conviction, he is liable to a fine at level 5 and to imprisonment for 2 years.

Similarly, Japan has stipulated legality requirements for data use, adopting the approach of charging the crime of refusing to comply with the data use security management obligation and criminalising the user if he refuses to comply with the security management obligation notified by the data protection authority. Article 19 of the Personal Information Protection Act amended in 2023 prohibits the improper use of personal information: Companies that process personal information must not use personal information in a way that incites or induces illegal or improper conduct. For example, providing personal information to another company suspected of engaging in illegal conduct, even if there is only the possibility of promoting illegal or improper conduct, is prohibited. Article 148 states the following: (1) if the Committee for the protection of personal information considers that an enterprise processing personal information has violated the provisions and needs to protect the rights and interests of individuals, it may recommend that the enterprise processing personal information or other related information stop illegal acts or take other necessary corrective measures; (2) if an enterprise that processes personal information or other related information receives the recommendations in the preceding paragraph and fails to take measures in accordance with the recommendations without justifiable reasons, the Committee may order the enterprise that processes personal information or other related information to take measures in accordance with the recommendations if it considers that the rights and interests of the individual will be seriously infringed upon; (3) if the Commission considers that an enterprise that processes personal information has violated the provisions of this article, it has seriously harmed the rights and interests of an individual and needs to take urgent measures, it may order the enterprise that processes personal information or other related information to stop illegal acts or take other necessary corrective measures. Article 178 provides for criminal responsibility: a person who violates an order in item (2) or (3) of Article 148 shall be sentenced to imprisonment of up to one year or a fine of up to 1 million yen.

The second type of criminalisation condition criminalises the illegal use of personal information by special groups in business, given their responsibility to protect personal information. For example, Article 179 of the Japanese Personal Information Protection Act states, “An enterprise with personal information, its employees or former employees who, for their own or a third party’s illegal interests, provide or misappropriate the personal information database or equivalent that they process in the course of business (including the personal information database or equivalent that has been copied or processed in whole or in part) shall be sentenced to imprisonment of not more than one year or a fine of not more than 500,000 yen.” Article 180 stipulates that anyone who provides or misappropriates personal information obtained by an administrative organ in the course of his or her career to seek illegal benefits for himself or herself or a third party shall be sentenced to imprisonment of up to one year or a fine of up to 500,000 yen.

However, the first type of limitation of the scope of criminalisation may require relevant actors to comply with the notice and thus avoid a criminal penalty, but there are other scenarios in which even the first-time violation is serious enough to be criminalised (see the illegality extent issue in Part 6). For the second type of limitation, special groups of actors do bear more duty to protect personal data, but other groups may also seriously infringe upon others (see the black industry chain in Part 5 and the illegality extent in Part 6). Therefore, these two types of criminalisation conditions should be valued, but they are inadequate from the perspective of legal techniques.

Overall criminalisation

The third type of criminalisation is that in which the illegal use of personal information is generally criminalised. For example, in addition to the crime of damaging reputation and credit and the crime of divulging secrets, to avoid incomprehensively protecting legal interests, the Personal Data Protection Act of Taiwan, China, also cites criminal means to compensate for the shortcomings of formal criminal law (Lu 2010). This act provides personal data comprehensive protection, which allows it to keep pace with technological developments. For example, in the criminalisation of deepfakes, the existing law already has provisions such as the crime of defamation and the protection act of personal data (Chen 2023). Article 41 of the Personal Data Protection Act of the Taiwan area of China states that in violation of either Article 6 (1) (no collection, processing or use of data relating to the medical records, health, genetic, sexual, medical and criminal records of natural persons, except in the exceptional circumstances listed), Article 15 (no collection or processing of other personal data by the government, Article 16 (governments shall not use other personal data except in the exceptional circumstances listed), Article 19 (nongovernmental organizations shall not collect or process other personal data except in the exceptional circumstances listed), or Article 20 (nongovernmental organizations shall not use other personal data except in the exceptional circumstances listed), causing damage to others; the actor shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of no more than five years and may be fined not more than NT $1 million.

Here, Taiwan prohibits the illegal use of special and other data by the government and nongovernmental organizations, thus cracking down on the illegal use of personal data in general. If the perpetrator violates the relevant provisions of the law without intent to act in the unlawful interests of himself or a third party or to harm the interests of others, it is sufficient to address civil damage and administrative penalties because of the low degree of culpability. Only when the perpetrator intends to violate the personal information law in the unlawful interests of himself or a third party or to harm the interests of others is the degree of blame high, in which situation a criminal penalty should be imposed. Considering the above intentions, Taiwan’s authoritative judicial ruling held that profit is limited to property interests, but damage to the interests of others is not limited to property interests and can include abstract personality interestsFootnote 4(Xue 2021). The interpretation of the profit from the illegal use of personal data can differ across jurisdictions. For historical reasons, e.g., East Germany Stasi, continental European countries are more alert to surveillance (Igo 2018, pp. 58–59).Footnote 5Germany has generally criminalised unauthorized processing of personal data that are not publicly available. This approach is coherent in addressing all kinds of processing methods for personal data in the same act. Article 42 (2) of the German Federal Data Protection Act 2017 provides for the unauthorized processing of personal data that are not publicly available, in exchange for payment or to profit oneself or others or harm others, with a penalty of up to two years in prison or a fine. Profit here is not limited to illegal interests but also includes the pursuit of legitimate interests, as long as there is no legitimate reason for the use of personal data, such as valid consent, which may limit the rampant use of internet browsing records (Liu 2022).

In summary, the choice and degree of criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information differ across jurisdictions. We need to consider whether China’s criminal law regulation of illegal use of personal information, if truly necessary and legitimate, must refer to the second model, represented by Hong Kong and Japan, of limiting the scope of criminalisation and moderating punishment after criminalisation or referring to the third model, represented by Taiwan and Germany, of overall criminalisation. For the second model, we should consider whether the way to limit the scope of criminalisation (see the ‘illegality extent’ issue in Part 6) is to set conditions such as ‘refusing to implement the notice of lawful use of personal information’ and ‘illegal use of personal information obtained by special groups in business’ or whether we should screen the types of behaviours worthy of criminalisation based on the potential harm of the types of behaviours of illegal use of personal information (Kröger et al. 2021; Privacy International 2018). For the third model, we still need to consider, from the perspective of legal techniques, whether there are exceptional legal reasons for using personal information and whether illegal use should be incorporated into the general term of ‘unlawful processing’ (Shutova 2022) or be listed separately. Specific comparisons and lessons between jurisdictions are further drawn in the following relevant parts. It is unlikely that the options and solutions of a particular jurisdiction would be suitable for any other jurisdiction, so we need to make a specific judgement based on the data theory and the legal system of civil law, data law and criminal law (Part 4) and the basis of legal policies of the personal data protection of a particular jurisdiction formed from the criminal situations of illegal use of personal data and other conduct (Part 5). Finally, we need to address the technical issues concerning criminalising the illegal use of personal data (Part 6).

Doctrinal legitimacy of the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal data

The illegal use of personal information causes nonnegligible harm in criminal law, which is an essential condition for criminalising the act. According to the theory of fair labelling, if an act commits unique harm, then the harm should be fully reflected in criminal law; otherwise, the characteristics of the act and the damage suffered by the victim are not fully reflected, which does not fulfil criminal justice (Chalmers and Fiona 2008). China should value this perspective of victimology and consider victims’ worth and need for protection as important factors in determining the worthiness and need for the penal treatment of an act (Hillenkamp 2018). Therefore, if the illegal use of personal information involves a unique infringement of legal interests compared with the existing offences of illegal acquisition and the illegal provision of personal information, this harm should be fully reflected in criminal law. This part concerns the outlying harms, particularly arising from big data and artificial intelligence (AI). There is a strong focus on use autonomy, but today, this issue also concerns the infringement of other legal interests, such as discrimination.

Independent protection of the use autonomy of personal data in data theory

The relationship between privacy protection and personal data protection is a legal issue that has a significant effect on civil rights and social development. To address this issue, scholars have proposed different views based on different legal cultures and social policies (De Hert and Gutwirth 2009; Gellert and Gutwirth 2013; Lynskey 2015, p. 90). Owing to length and subject matter, this article does not debate which position is correct on a macro level. This article proposes that the data theory that conforms to the current legal system of a jurisdiction is the desirable position of that jurisdiction. Both civil law and criminal law in China confused privacy and personal information protection in the early stage, leading to the continuation of the privacy protection mode of the personal information crime clause, which focused on information transfer but failed to examine criminal law needs for personal information protection from the perspective of the full life cycle of the processing of personal information.

Article 2 of the Tort Liability Law enacted in 2009 explicitly stipulates the right to privacy, which is protected by civil law as a civil right. Since then, civil law has explicitly recognized the right to privacy, and Chinese judicial organs have begun to protect this right on a large scale and to try to use it to protect personal information. Article 12 of the Provisions on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law to Civil Disputes Involving Infringement of Personal Rights and Interests through Information Networks issued by the Supreme People’s Court in 2014 stipulates: ‘Where network users or network service providers use the internet to disclose personal privacy and other personal information of natural persons, such as genetic information, medical records, health examination data, criminal records, home addresses, private activities, etc., causing damage to others, and the infringed party requests it to bear tort liability, the people’s court shall support it.’ According to this statement, personal privacy is personal information, and there is no substantive difference between the two. However, because the Tort Liability Law only explicitly stipulates the right to privacy, the infringement of other personal information is entitled to the relief rules of privacy. Importantly, the applicable privacy relief rules at this time are designed with respect to the situation of information disclosure, so the relief of personal information is also based on the premise of information disclosure. Article 1 of the 2012 Decision (a single piece of statutory law) of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on Strengthening the Protection of Online Information stipulates that ‘the state protects electronic information that can identify citizens’ identities and involve citizens’ privacy. No organization or individual may steal or otherwise illegally obtain the personal electronic information of citizens, sell or illegally provide the personal electronic information of citizens to others.’ There is still a gap between the concept of ‘citizens’ personal electronic information’ used here and the concept of citizens’ personal information. Although it is divided into electronic information that can identify a citizen’s personal identity and electronic information that involves a citizen’s privacy, judicial authorities generally consider both of them to be information worthy of protection without substantial differences and often hold that, according to this decision, the protection of both is limited to the scenarios of illegal acquisition and illegal disclosure; that is, both focus only on whether the information is transferred (Guo 2024).

Similarly, Chinese criminal law has taken the position of protecting personal information through information transfer. Since 1979, criminal law has protected some core privacy issues in terms of the crimes of trespassing, illegal search, and the divulging of communication secrets, but its stance is based on whether privacy is illegally obtained. Owing to this logic, the protection of personal information in criminal law adopts the perspective of whether personal information is illegally obtained or illegally sold. In 2009, the Seventh Amendment to the Criminal Law added the crime of selling and illegally providing citizens’ personal information and the crime of illegally obtaining citizens’ personal information, making it illegal for employees of state organs or financial, telecommunications, transportation, education, medical and other institutions to violate state regulations by transferring citizens’ personal information obtained in the course of performing their duties or providing services. The act of selling or illegally providing to others, when circumstances are serious, should be regulated. The reason is that ‘some state organs, telecommunications, financial and other units in the performance of official duties or the provision of services to obtain citizens’ personal information are illegally leaked from time to time, posing a serious threat to citizens’ personal, property security and personal privacy’ (Gao 2012, p. 477). At this time, the protection of personal information in criminal law adopts the protection mode of privacy, which is limited to whether the information is transferred from the right holder to the third party. In 2015, the Criminal Law Amendment (IX) expanded the scope of criminal subjects to include any person or unit that violates state regulations by obtaining, selling, or providing citizens’ personal information. Cases where the circumstances are serious and involve the commission of a crime and, in the course of performing duties or providing services to supply or sell citizens’ personal information to others, face heavier punishments. Accordingly, the charges are integrated into the crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information. Currently, the protection stance, which concerns only whether personal information is transferred, continues to hold.

Although it is essentially reasonable for privacy protection to focus only on whether the information is transferred from the perspective of contemporary jurisprudence, this focus is unreasonable for personal information protection. The right to privacy is closely related to human dignity and is primarily a right of passive defence that can be claimed when violated by others, whereas personal information is a more active right that can be actively controlled and used by both the right holder and others according to established rules (Zhou 2018). Traditionally, privacy infringement is an intrusion. The main infringement methods of private activities, private space, and private information are entering, shooting, snooping, eavesdropping, and making information public. As long as private activity information, private space information, and private information are illegally obtained (the information does not even need to be illegally disclosed), a direct violation of the basic dignity of the right subject as a natural person has occurred. Therefore, Article 1032 of the Civil Code stipulates that the content of privacy can be addressed only if the privacy subject explicitly consents or if the law passed by the National People’s Congress and its standing committee otherwise allows.

Personal information must be used; if is not allowed, it loses value (Lynskey 2015, pp. 47–50; Guo 2024). The protection of personal information is based on personal information self-determination. Individuals have reasonable control over the entire life cycle of their personal information. With respect to openness and sharing, the ownership and control of personal information in the information network era have been normally separated. This separation is often legal; that is, based on individual sharing, transfer, authorization, or legal provisions, others can legally control the information, but the information subject still enjoys legal protection. In terms of processing stages other than disclosure and sharing, the use of personal information is becoming increasingly technically feasible and economically beneficial in the era of big data (Hilbert 2016; Loideain 2019). In that case, it is necessary to control or safeguard ‘on what data is shared, whom it is shared with, or for what purposes data is used or reused’. The value of this type of use possesses characteristics not of personality or exclusiveness, such as privacy, but rather of multiparty sharing and exchange. The right regarding personal information is not limited to passively preventing others from obtaining and disclosing one’s personal information but also includes the ability to independently decide under what circumstances others can obtain and disclose one’s personal information in what purpose, way, and degree and to independently decide under what circumstances to use one’s personal information in what purpose, way and degree (use autonomy). The transfer power to decide that others can obtain and disclose personal information is the preliminary power, whereas the use power to decide that others can use personal information is the core power, which determines the motivation and direction of the exercise of the transfer power (Li 2019). In the era of the development of the digital economy and artificial intelligence, the status of the right to use is increasingly important in the full life cycle of the autonomous operation of personal information.

Independent protection of the use autonomy of personal data in the legal order

The unified regulation of the illegal use of personal information by criminal law can contribute to the expression function of coherent rules in the whole legal order of civil law, data law and criminal law. In principle, criminal law as a last resort serves as a guarantee of the preceding civil and administrative laws (Sun 2012), such as the Chinese Civil Code and the Personal Information Protection Law. If the mode of personal information protection in the preceding law has changed significantly, then the mode of personal information protection in criminal law should also change accordingly to achieve the coherent purpose of an overall legal order. Otherwise, not only can we not effectively regulate personal information infringement behaviour, but we may also damage the overall legal structure of personal information protection.

From the perspective of the overall legal structure of personal information protection, criminal law should be updated according to the preceding laws. The preceding laws of criminal law have begun to cultivate systematic security thinking for the acquisition, storage, and use of personal information. In China’s criminal legal system, the protection of personal information should not be limited to the mode of privacy protection that focuses on information transfer. The scope and intensity of protection of personal information should also be explored from the perspective of the whole cycle of personal information processing. The General Provisions of the Civil Law enacted in 2017 refer to the right to privacy and personal information in Articles 110 and 111, respectively, which conceptually indicates to the judicial authorities that the two, although closely related, have different rights and interests. However, the law does not clearly define the contents of the two, which makes it possible for judicial organs to still use the right to privacy to protect personal information or personal information to protect privacy in practice. Fortunately, Article 76 of the Cybersecurity Law enacted in 2016 stipulates that personal information refers to all kinds of information recorded electronically or in other ways that can identify a natural person’s identity alone or in combination with other information, including but not limited to the natural person’s name, date of birth, ID number, personal biometric information, address, and telephone number. This article explicitly states that the judicial authorities shall apply the provisions of personal information to protect the case by the definition of personal information; only in cases that do not meet the definition of personal information can we consider applying the terms of privacy protection. This statement establishes the dual protection of privacy and personal information at both the legislative and judicial levels. In addition, the Civil Code enacted in 2020 systematically provides ‘protection of privacy and personal information’ in Chapter VI. Article 1032 defines privacy as follows: ‘Privacy is the private space, private activities, and private information that a natural person has in his or her private life and is unwilling to be known to others.’ Article 4 of the Personal Information Protection Act 2021 defines the definition and type of processing of personal information as follows: ‘Personal information is information recorded electronically or by other means relating to an identified or identifiable natural person, excluding information that has been anonymized. The processing of personal information includes the collection, storage, use, processing, transmission, provision, disclosure and deletion of personal information.’ These provisions clarify once again that the protection of privacy and personal information should, in principle, be binary and parallel. Personal information should have its own independent and complete protection mode.

From the perspective of effectively regulating personal information infringement behaviour, criminal law should be updated according to the preceding laws. Current criminal law focuses only on the illegal acquisition, sale, and transfer of personal information, adopting a piecemeal, ad hoc, and reactive approach that currently fails to match the scope and extent of the illegal infringement of personal information. A lack of agreement concerning the definition and liability of the illegal use of personal information makes it difficult to enforce legal compliance, and most information users choose to create their form of best practice rather than follow explicit industry advice. Therefore, we should fully express society’s condemnation of illegal phenomena and its demand for justice, redress, and change through a coherent legal response (McGlynn and Rackley 2017). Like behaviour in general, law has an expressive function (Sunstein 1996). This function can be used to promote cultural change. Law conveys, affirms, solidifies, and restores existing social norms, commitments, and beliefs while clarifying new ones and plays a key role in protecting our rights to be treated as members of society with a good and civilized capacity (Waldron 2012; McGlynn and Rackley 2017). This combination of identification and formation has played a key role in addressing the issue of information technology-based personal information infringement (illegal use), enabling the law to be enforced. A coherent, and therefore clear, widely known and understood framework of criminal law provisions and judicial interpretation can create an important cultural climate of respect for personal information and trust in legal protection in the information technology environment to prevent the approval and establishment of an industry and culture that uses information technology solely as an object of exploitation.

Independent protection of the use autonomy of personal data for substantive interests

From the perspective of criminal law doctrine, whether an act should be considered criminal depends first on the threat of infringement to the interests protected by criminal law and requires comprehensive consideration of the possibility of harm (Feinberg 1984, p.216) and the urgency of such harm (Guo 2023). The urgency of harm affects the ability of the victim and the public authority to intervene in time to reduce and eliminate the possibility of harm. The illegal use of personal information is more urgent than the unlawful acquisition and provision of personal information. The act of illegally obtaining and providing personal information obviously infringes only on the right to transfer personal information in an abstract sense and cannot directly infringe on the substantive rights and interests of the information subject, such as personal safety and property safety, and the substantive harm to the information subject is still far removed. A hacker can obtain bank details, but the money is still in the account. Illegal uses of personal information, such as creating personal portraits, further telecommunications network marketing, and travel tracking, cause direct harm to the substantive rights and interests of the personal information subject. For example, harassing marketing will directly infringe on the peace of the personal information subject; discriminating against familiar guests based on the big data of customers and the personal data of familiar guests will directly infringe on the right to fair trade; and precise fraud via personal information will directly infringe on the property of the personal information subject and even lead to suicide, self-harm, and other personal harm consequences.

Criminal law does not consider trivial matters; otherwise, it would violate the principle of proportionality, and ultimately, the gain is not worth the loss (Baker 2011, Chapter 3). Therefore, all types of infringement of personal information to be combated by criminal law can cause serious harm. The illegal use of personal information is precise in terms of the damage it causes, whereas the unlawful acquisition and provision of personal information tends to be more large scale. Personal information is identifiable, but this characteristic is often reflected only as a possibility under circumstances of illegal acquisition and illegal provision; that is, the actor may identify a large number of victims, but if the actor has no purpose of directly using personal information, the actor often will not take time and effort to convert this possibility into reality. In the case of illegal use, the perpetrator will spend the necessary time and energy to link each piece of personal information to a specific subject and then carry out marketing, identity theft, or telecommunications network fraud and other personal information use activities against the particular subject (Liu and Song 2022). The harm of illegally obtaining and illegally providing personal information is cumulative, i.e., the infringement on the personal information transfer power of a large number of individuals has reached the criminal requirements of serious harm. The illegal use of personal information can easily have a significant effect on the rights and interests of specific individuals; thus, the amount of illegally used personal information likely does not need to be very large to meet the requirements of serious harm required for criminal law intervention.

Policy necessity of criminalising the illegal use of personal data

Another necessary condition of criminalisation is compliance with criminal policy. From the perspective of criminal policy, behaviour that interferes with use autonomy and other legal interests can be a candidate for criminalisation, but the criminal law system would adopt either a stern or a lenient standing towards conduct according to policy considerations (Ma 2007). These policy considerations can vary and be vague in different jurisdictions, but we can refer to a mature framework. According to the legislative rationale specified in the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code, criminal law should combat harmful conduct that disrupts the sense of security of the community, which either is particularly harmful or is less harmful but more likely to be inflicted on others by those who clearly have no respect for the rights of others.Footnote 6 In jurisdictions where information technology such as big data and AI is widely available, such as China, the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal information generally meets both criminal policy grounds. When a tort meets criminal policy grounds, it can be considered criminal law.

Egregious nature of the illegal use of sensitive personal data

The illegal use of sensitive personal information is likely to cause particularly serious harm. Sensitive personal information is defined in Article 28 of China’s Personal Information Protection Law as ‘personal information that, once leaked or illegally used, is likely to lead to the violation of the human dignity of natural persons or harm the personal or property safety, including biometric information, religious beliefs, specific identities, medical and health information, financial accounts, whereabouts, etc., and personal information of minors under 14 years of age.’ This definition reveals that the illegal use of sensitive personal information can easily lead to serious harm to human dignity or personal or property safety. If this type of behaviour is one-time and accidental, the nature of its harm generally does not reach the particularly serious degree of murder, arson, rape, or pillage; however, if a certain amount and time limit are superimposed, the overall degree of harm will be particularly serious and should receive attention from criminal law.

In recent years, Chinese scholars have begun to examine the illegal use of special types of personal information. For example, facial information is an example of sensitive biometric information. Technically, a deep fake also involves the use of personal biometric information. The front-end liability thinking of citizens’ personal information protection, which focuses on illegal acquisition behaviour, ignores the independence of legal interest in infringing on deepfake behaviour and the special need for personal biometric information protection. It is argued that the normative nature of deepfakes is identity theft, so it is necessary to introduce the concept of identity theft in criminal law to compensate for the gap in criminal law evaluation concerning the ‘legal acquisition + illegal use’ of personal information (Li 2020). Identity theft causes harm different from, but more serious than, the simple illegal acquisition of personal information (Ribet 2023). Some scholars have proposed that in addition to the general characteristics of personal information, personal financial information has outstanding characteristics, such as a significant economy and considerable credit, because it occurs in financial activities. The illegal use of personal financial information seriously infringes on individuals’ privacy and individuals’ property rights, promotes many downstream crimes, such as money laundering and telecom fraud, damages the reputation of financial institutions, hinders the development of the financial industry, and has many negative effects on financial stability and the financial environment. At the legislative level, the crime of the illegal use of personal financial information should be added (Li 2019). In this context, the use of some sensitive personal information violates the personal dignity of an individual, a particularly important personal right, because some sensitive personal information involves private information in personal privacy, which requires more legal regulation than does the ordinary infringement of personal information that does not involve private information.

Worse situation of the large-scale illegal use of ordinary personal data

Although the illegal use of ordinary personal information is less harmful than the illegal use of sensitive personal information, it is more likely to be imposed on ordinary citizens by criminals who clearly do not respect the personal information of ordinary citizens. Scholars have noted that the illegal use of personal information has become increasingly fierce, driven by excessive profits. The crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information has gradually formed a complete data transaction black industrial chain of ‘provider - middleman - illegal user’, with a clear division of labour and tight organization with respect to each link. That is, personal information is clearly priced, upstream ‘middlemen’ are responsible for illegally obtaining, selling, and providing personal information, and downstream demand groups buy and use personal information to carry out various illegal and criminal activities. These phenomena include using other people’s personal information to maliciously register internet accounts, fraudulently using personal information to apply for credit loans or tax evasion, stealing personal information to hack the identity authentication system, abusing personal information to make harassing false marketing calls, pushing harmful information, and causing illegal debt collection to become increasingly serious (Cao 2019; Liu 2020). The industry model of making profits by illegally using personal information to carry out criminal activities is the root cause of personal information leakage and the proliferation of illegal transactions. The illegal use of personal information is a downstream behaviour, causing great damage to or threats to citizens’ personal and property safety and social management order. Compared with the upstream illegal transfer of personal information, the illegal use of personal information involves more serious infringement of legal interests, which manifests as the root, direct, and precise infringement of legal interests (Liu and Li 2022). In 2023, the Beijing Higher People’s Court issued the White Paper on the Trial of Crimes of Infringing Citizens’ Personal Information, which noted that crimes infringing on citizens’ personal information are frequent and that nearly 40% of these crimes are used for illegal and criminal activities (Lin 2023). In the eyes of the actors involved in the personal information black industry chain, the subject of personal information is only the object of their profit-making illegal and criminal activities, and they do not consider the subject status of the other party. This black industrial chain subculture atmosphere that does not respect the subject status of others’ personal information should receive attention and be managed; otherwise, it will be interfere with the need to promote the development of information networking in a country. By definition, criminals cannot care less about their victims’ personal data. However, this kind of personal character disrupts the sense of security of the community and should be targeted by criminal law.

An important reason why practitioners in the black industry chain apparently do not respect the autonomy of the use of personal information is that the current criminal justice system does not demonstrate effective crime prevention. The illegal use of personal information is more direct and results in even higher profit than does the unlawful acquisition and provision of personal information, so the temptation to commit this behaviour is greater. On the other hand, although this behaviour is easier to detect than the illegal acquisition and provision of personal information is, it is currently not punishable by criminal law. That is, it is difficult for citizens to discover that their personal information is illegally obtained, sold, and provided, and even if they make this discovery, it is difficult to find the perpetrator by themselves, while it is relatively easy for citizens to find that their personal information has been used. In this case, if the illegal use of personal information is not criminalised, citizens seeking public relief may not be accepted or may be rejected by public authorities (Tian 2023). Because the chain of behaviours of illegally obtaining, selling, and providing personal information is long and complex, it is difficult for victims and judicial organs to identify every specific perpetrator, whereas the nodes of illegal use of personal information are easier to detect, and it is thus easier for victims and judicial organs to identify the particular perpetrators of illegal use. If the easily identified actor is not deterred by a penalty, then the actor who directly uses personal information to make an enormous profit will naturally tend not to respect the autonomy of using personal information. The situation is that, where the commercial benefits of using personal data, for example, through targeted advertising, are substantial, the current milder sanctions against abuse often fail to deter it (Zharova and Vladimir 2017). Illegal use is thus more likely to be inflicted on data subjects, which exacerbates the subculture atmosphere that does not respect others’ subject status.

Technical feasibility of criminalising the illegal use of personal data

For scientific legislation, the criminalisation of the illegal use of personal data should balance the protection of personal data and the interests of relevant parties (Gaagouch 2024). Criminalisation might lead to further legal uncertainties in practice and create additional hurdles for data controllers, processors and collectors, which could hinder the usage of personal data as well as the free flow of such data, ultimately impacting innovation in general. However, a balance can be achieved, and the potential chilling effect of overly strict data protection regimes on the market can be avoided by criminal law techniques of setting high and clear illegality extent requirements for personal data use, requiring diversified and practical justifications for personal data use, and establishing proportionate and clear penalty ranges for the illegal use of personal data.

Illegality extent of personal data use in criminalisation

For criminalisation technology, we should be able to determine the extent of the illegality of various personal data use scenarios. Based on the argument of the necessity of criminalisation, we should distinguish the abuse of information from ordinary illegal use and include the abuse of information under the crime of infringing on citizens’ personal information (Li 2019; Gon and Li 2022). As summarized in the second part of this article, limiting the scope of criminalisation and differentiating criminalisable abuse of personal data from ordinary illegal use can be a way of setting criminalisation conditions such as ex post ‘refusal to perform official notice’ or belonging to ‘special groups of actors on duty’ in the laws of Japan and Hong Kong, but the types of behaviours that qualify as criminal should generally be screened according to the potential harm caused by the specific types of illegal use of personal information. More specifically, it should be determined whether the necessary severity for criminalisation is achieved according to the degree of infringement of the specific behaviour type on the autonomy of using personal information, the degree of harm to other legal interests, and the degree of personal danger to the perpetrator.

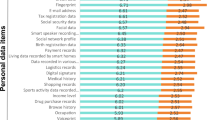

First, in terms of the extent of infringement of the freedom to use personal information, the illegal use of others’ personal information and the direct infringement of others’ major interests seriously infringe on the autonomy to use personal information and should be criminalised. (1) The illegal use of personal information to infringe on the types of interests already protected by criminal law can be used as a clear criminalisation threshold. For example, the 2020 amendment to the Criminal Law added Article 280, titled ‘crime of impostor’, to protect citizens’ admission qualifications for higher education, civil service employment qualifications, and employment placement treatment, which increased the types of interest protected by criminal law. In practice, such cases have occurred. By convincing candidates to enter their details in a ‘preregistration system’, the perpetrator illegally obtained the information used by candidates to log into the college choice registration system and then, against the wishes of candidates, arbitrarily filled in another application for college A, resulting in a total of 11 students being wrongly admitted to college A.Footnote 7 In this case, the degree of infringement on the use autonomy of personal information should be considered to have reached the threshold of crime. (2) The fraudulent use of personal information, unauthorized use of personal information, forgery, and alteration of personal information in other scenarios, if enough to cause the information subject to bear the consequences of crime or enough to prompt the perpetrator to commit criminal acts, should be considered to have reached the threshold of criminalisation. These situations include the misappropriation of other people’s information for telecommunications and network fraud, unauthorized use of other people’s information for illegal business activities, forgery, alteration of other people’s information for the production and dissemination of obscene materials, extortion, and fraud. (3) For the fraudulent use of multiple types of personal information, unauthorized use of multiple types of personal information, forgery, or the alteration of multiple types of personal information in other scenarios, although the interests of each individual are minor, the cumulative degree of infringement on the use of personal information autonomy is serious, so illegal use should be criminalised. The organizational and systematic use of personal information is the basic form of the illegal use of personal information (Jian 2022). Article 5, paragraph 1, items 3–7 of the Interpretation of Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in Handling Criminal Cases involving Infringement of Citizens’ Personal Information by the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate stipulate the quantitative conditions for illegally obtaining, providing, and selling multiple types of personal information and infringing on the autonomy of personal information transfer to a serious degree: illegally obtaining, selling or providing 50 or more items of whereabouts and tracking information and communication contents, credit information or property information; illegally obtaining, selling or providing 500 or more items of accommodation information, communication records, health and physiological information, transaction information and other personal information of citizens that may affect the safety of a person and property; illegally obtaining, selling or providing 5000 or more items of citizens’ personal information other than those provided for the items above; and illegal gains of 5000 yuan or more. The illegal use of personal information is a violation of personal information use autonomy that is no less serious than the illegal acquisition, provision, and sale of personal information. Therefore, the above criminalisation standards should apply to the illegal use of personal information, especially in the scenario of automated decision-making and personal portraits.

Second, in terms of the infringement of other interests, the illegal use of personal information obtained by special groups relying on business convenience not only infringes on the use autonomy of personal information but also infringes on the trust of users and the public in the legitimacy and security of special businesses and should be criminalised. When an organization or other unit authorized by a state organ, law, or regulation to manage public affairs uses, unlawfully uses, forges, or alters a citizen’s personal information obtained in the course of performing its duties or providing services, this behaviour should be criminalised. In addition, concerning the provisions of Article 5, paragraphs 1 and 8 of the above judicial interpretation, the criminal standards for the illegal sale and provision of personal information by special groups are halved, and those who illegally use the personal information of citizens obtained in the process of performing duties or providing services, the amount of which reaches more than half of the criminal standards for the above illegal use of multiple types of personal information, should also be criminalised.