Abstract

Several countries have introduced dedicated national climate ministries in the last two decades. However, we know little about the consequences of these ministries. We demonstrate that the introduction of climate ministries helps to reduce carbon emissions. A difference-in-differences analysis of a global sample of countries reveals robust and statistically significant evidence that introducing a dedicated climate ministry lowers carbon emissions substantially. At the same time, establishing such climate ministries does not significantly influence the introduction of new climate policies. This indicates that climate ministries primarily amplify climate action by improving the effectiveness of the governmental measures taken rather than by increasing the number of climate policies themselves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To effectively combat escalating climate change, governments must take decisive action to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In recent times, the discourse has shifted from the question of how to achieve international cooperation to the question of how to design national public institutions to foster climate actions1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Specifically, the role of establishing dedicated climate ministries has risen to the forefront of this scholarly debate8,9. Dedicated climate ministries are considered potential catalysts for driving comprehensive and concerted efforts toward climate action. The main argument is that climate ministries come with clearer responsibilities and increased administrative resources dedicated to addressing the issue of climate change.

Despite these supposed advantages of dedicated climate ministries, empirical evidence regarding their actual impact on climate policy ambitions and effectiveness remains scarce. We address this research gap by examining a comprehensive sample of 169 countries over a span of two decades (2000 to 2021). We use a difference-in-differences (DiD) design to investigate whether establishing a dedicated climate ministry makes a difference in terms of the quantity, type, and effectiveness of climate policies. We compare countries that have introduced a dedicated climate ministry to those that have not. Our analysis reveals that the establishment of dedicated climate ministries contributes to a reduction in carbon emissions. Yet, it does not significantly influence the introduction of new climate policy legislation. Instead, variations in carbon emissions appear to be driven largely by the enhanced effectiveness in the implementation and enforcement of existing climate policies.

The paper is structured as follows: First, we discuss the purported advantages of climate ministries in addressing climate change. Next, we conduct a comprehensive mapping of existing climate ministries and analyze the impact of their introduction on carbon emissions. Furthermore, we assess the mechanisms that link the establishment of a dedicated climate ministry with carbon emission reduction. Thereafter, we discuss our results. The final chapter presents our research design and methodologies.

The benefits of dedicated climate ministries

Dedicated climate ministry come with two central benefits. The creation of a dedicated climate ministry helps to ensure clear lines of responsibility5,10. Moreover, the creation of a dedicated climate ministry guarantees that specific administrative resources, in terms of both staff and budget, are allocated to addressing climate change issues. These advantages can enhance climate action through different mechanisms.

First, governments can leverage such specialized ministries to reduce CO2 emissions through policy formulation. This can be achieved through the proliferation of more, stricter, or better “designed” policies. A climate ministry crystallizes accountability, clearly delineating the responsibility for initiating and steering climate actions. In government structures without a dedicated climate ministry, climate-related policy responsibilities are often spread across various ministries or departments, such as those dealing with energy, environment, or industry11. It is thus often unclear who (exactly) needs to take the measures it needs to tackle climate change. In addition, even though comprehensive climate action still requires the collaborative effort of various government sectors, a climate ministry can drive cross-ministerial coordination, compelling other departments to take necessary steps12. Moreover, the augmented administrative capacities that come with climate ministry can empower governments to formulate more and “better” policies. As emphasized by Fernández-i-Marín et al., the creation of well-designed policies is not a straightforward task – it requires a substantial level of administrative capacity13. The establishment of a climate ministry, with its focused mandate and specialized workforce, can significantly contribute to the development and execution of these policies.

Second, climate ministries play a pivotal role in enhancing the effectiveness of a country’s climate policy through better enforcement and implementation practices. Climate ministers typically do not implement policies directly but delegate this task to governmental agencies or administrative bodies situated at different levels of government14. A key insight from the policy implementation literature is that during this process, things might not transpire as intended, since other levels of government might, for various reasons, fail to take the requisite action to render a policy effective. These reasons can include conflicting priorities, lack of clear guidance or insufficient expertise, political opposition, or challenges in coordination and communication across the multiple agencies involved15. Equipped with dedicated workforces and financial resources, a climate ministry can monitor various enforcement agencies to ensure they are executing policies as intended and assist subordinate levels of government in adhering to climate objectives. Steinebach, for instance, finds that clean air policies are more effective in reducing air pollutant emissions when the implementation process is overseen by a specialized central ministry16. Figure 1 summarizes these theoretical considerations.

Mapping dedicated climate ministries

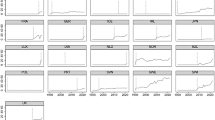

Figure 2 presents the number of countries with a dedicated climate ministry over time. The first ministry portfolio carrying “climate” in the organizational title was the “Minister of Climate Change Issues” created in New Zealand in 2005. Of the 38 countries that have introduced a climate ministry at some point in time, 30 still had a ministry in 2021. Interestingly, in only five countries, these ministries were solely responsible for climate matters. In most instances, the portfolio of these climate-centric ministries was merged with at least one other policy ___domain, typically either “environment” or “energy”.

Looking at the geographical distribution of climate ministries (Fig. 3), we can see that starting with Belgium and Denmark in 2007, many European countries have introduced dedicated climate ministries in the last two decades. However, climate ministries are not exclusively a Western phenomenon. Several countries in the “Global South” such as Gabon, India, and Papua New Guinea have established climate ministries as well (see also Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material).

Climate ministries and carbon emissions

In the next step, we conduct an econometric analysis to identify whether the introduction of a dedicated climate ministry affects carbon emissions. As detailed below in the method section, we use a difference-in-differences design to look at changes in carbon emissions up to 5 years before and after establishing a dedicated climate ministry. We then compare emission trajectories to countries that have not introduced a climate ministry in the same period and use a matching technique to only compare countries with similar covariate trajectories17.

As shown in Fig. 4, our empirical results strongly support dedicated climate ministries’ emission-reduction potential. In the year after the establishment of a ministry, emissions drop on average by more than 0.36 metric tons per capita (95% confidence interval of −0.71 to −0.04 metric tons per capita) compared to countries that have not introduced a climate ministry. This effect is statistically significant at the 5% level and increases further to around 1.06 metric tons per capita (95% confidence interval of −1.87 to −0.29 metric tons per capita) after 5 years. This effect not only proves to be statistically significant but also quite substantial. The emission savings after 5 years equates to roughly one-eighth (12.5 percent) of the average per capita emissions in OECD countries. In other words, establishing a climate ministry substantially reduces carbon emissions. In contrast, emission trajectories do not differ between countries before the establishment of a dedicated climate ministry. Thus, the parallel trend assumption holds, i.e., the identified effects on carbon emissions are not a continuation of diverging emission trajectories prior to the introduction of climate ministries.

What are the mechanisms driving this emission reduction?

As discussed above, climate ministries can help governments to achieve emission reductions in different ways. First, by formulating more, more ambitious, and “better” climate policies. Second, by enhancing the enforcement and application of existing climate policies.

To assess whether the establishment of climate ministries leads to more climate policies, we take the total number of climate mitigation policies from the Climate Policy Database18 and use the same econometric difference-in-differences technique to estimate the effect of dedicated climate ministries on climate policy outputs. The results show no statistically significant differences between countries that have introduced a dedicated climate ministry and those that have not (Fig. 5, left panel). On average countries do not levy more climate policies after establishing a ministry. Furthermore, there are no diverging trends in climate policy-making prior to the establishment of a climate ministry. Thus, the emission-reduction effect of establishing a climate ministry cannot be explained by a simultaneous increase in policies.

Certainly, evaluating the influence of climate ministries on the overall count of policies overlooks the distinctions in the various types of policies that governments can use to address climate change. Governments have an array of both “soft” and “hard” climate policy instruments at their disposal19,20. Notably, regulatory and market-based instruments—particularly carbon trading and taxes – are considered more ambitious measures in climate policy21. However, we do not find a statistically significant effect of climate ministries on these ambitious climate policies either (Fig. 5, middle panel). On average, countries that established a climate ministry do not have a statistically higher likelihood of introducing more ambitious regulatory or market-based climate policies.

Furthermore, it might be the case that the establishment of a climate ministry leads to better designed policies. Government might make use of a more diverse range of climate policies to demand-tailor policies to tackle climate issues. To test this, we look at the impact of the establishment of a climate ministry on the average instrument diversity (AID) of climate mitigation policies. This measure, as proposed by Fernández-i-Marín et al., measures the policy design quality based on the degree to which governments use different instruments and instruments combinations across the various policy targets and sectors they address13. The underlying logic is that a greater instrument diversity reflects a greater effort of the government to find “tailor-made” solutions to the different policy problems they address. We do not find a statistically significant effect of the establishment of a climate ministry on instrument diversity (Fig. 5, right panel).

We run several additional models to check for the sensitivity of our data and the accuracy of our model choice. First, we run our models without using the matching algorithm (Fig. S5), by additionally matching on leadership changes (Fig. S6) as well as on green party government participation (Fig. S8), and by only looking at ministries where the climate minister is the head of the ministry (Fig. S7). Findings are robust. Furthermore, instead of running a difference-in-differences analysis, we test for the influence of climate ministries on carbon emission in an ordinary time-series cross-section-analysis (Table S1). In this analysis, the presence (or absence) of climate ministries is quantified using a binary dummy variable. Again, our analysis shows that having a climate ministry is a statistically significant and robust predictor of bigger reductions in CO2. In the full model that includes various control variables and a lagged dependent variable, CO2 emissions per capita decrease by 0.16 metric tons more for each year a country has a dedicated climate ministry.

In sum, these findings indicate that introducing a climate ministry does neither lead to more nor to more ambitious or better-designed policies. This renders the improved implementation and enforcement of existing climate policies as the most plausible explanatory factors for the observed differences. The key argument here is that the clearer delineation of responsibilities and the provision of extra administrative resources within these ministries improve the government’s capacity to supervise the implementation authorities16.

We probe this argument in three additional analyses. First, we differentiate between specialized and general ministries. We define general ministries as those that focus on at least three additional issue areas next to climate change, while more specialized ministries are defined as dealing with a maximum of two additional issues. The heterogeneity of ministries’ portfolios should come at the cost of undermining the observed effects on improved implementation as responsibility gets blurred and additional (specialized) administrative resources are less plentiful8. In line with this theoretical expectation, we do not find any effect of these ministries that deal with climate as one of several topics on carbon emissions (Fig. S2 left panel). In contrast, we do find a strong effect of establishing a more specialized climate ministry (Fig. S2 right panel).

Second, we look at the effect of general environmental ministries on carbon emissions. In contrast to climate ministries, environmental ministries are not solely focused on climate action but typically deal with various topics such as air pollution in general, water pollution and nature conservation. Using the same econometric technique, we find no robust statistically significant effect of establishing a general environmental ministry on carbon emissions per capita (Fig. S3). This further supports the argument that the specialization of dedicated climate ministries is key for reducing carbon emissions.

Finally, we check whether the effect of having a climate ministry varies between countries. In line with our arguments about the importance of implementation effectiveness, we would expect that new climate ministries are less likely to improve policy implementation in countries with lower overall state capacity. In other words, a lack of general state capacity undermines the effect of establishing new institutional structures. Overcoming disjointed responsibilities and making sure additional resources are used for implementation purposes is harder when the state generally lacks power and authority. This is well in line with previous research indicating that general state capacity is a crucial determinant of a country’s capability to build up more effective administrative structures to tackle climate change22.

We test for heterogenous treatment effects in two ways. First, we re-run the previous analyses but leave out individual countries that have established a dedicated climate ministry. The effect of climate ministries on emission after 5 years stays robust (Fig. S4). This ensures that our findings are not driven by extraordinary emission reductions in specific countries. The analysis further indicates that the observed effect on CO2 becomes markedly stronger when excluding countries with particularly low state capacity, such as India, Oman, Gambia, Zimbabwe, and Papua New Guinea. Given that these states may encounter more significant challenges in establishing effective administrative structures, despite potentially having the best intentions, this finding reinforces our assertion that the creation of climate ministries does indeed make a difference by enhancing administrative capacities.

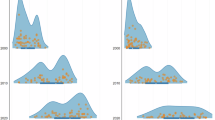

Second, we make use of the time-series cross-sectional analysis presented. This econometric set up allows us to conduct a statistical test which checks whether the effect of having a climate ministry varies by overall state capacity. To do this, we run a model with an interaction effect. More precisely, we use the full Model 4 in Table S1 and expand it by interacting the climate dummy with generate a general state capacity index developed by Hanson and Sigman23 who use Bayesian latent variable analysis covering a wide range of indicators related to different state capacity dimensions. To interpret the interaction effect, we present marginal effect plots24. Furthermore, we add a histogram to the plot and use a binning estimator developed by Hainmueller et al.25. The estimator splits the data into three different bins (high, medium, low) and estimates whether the effect of having a climate ministry varies between the different bins. As shown in Fig. 6, our results show that the effect of a climate ministry on carbon emissions is substantially stronger for countries with overall higher levels of state capacity. In contrast, the effect is indistinguishable from zero in countries with lower levels of state capacity. In sum, these findings show support for our argument about the crucial role of climate ministries in enhancing the effectiveness of climate policy. In countries with substantive state capacity, climate ministries help to lower emissions substantially, while lacking state capacity undermines the mechanism of increased implementation effectiveness fundamentally.

The figure present the effect of establishing a dedicated climate Ministries on per capita CO2 emissions for different levels of state capacity. Its plots show the estimated marginal effects using both the conventional linear interaction model and the binning estimator. The gray areas show the 95% confidence intervals. The histogram shows the distribution of the moderator variable by differentiating between countries with (red bars) and without (grey bars) a climate ministry in a respective year.

It is important to emphasize that our findings substantially dismiss the notion that the observed impacts of climate ministries are merely a “by-product” of an overarching rise in governmental climate ambitions. If the creation of these ministries were simply a reflection of an underlying process of increased governmental commitment towards climate action, we would expect to see ministry formation going hand in hand with adopting more, or more ambitious, policies. Similarly, given the absence of a trend before the creation of a climate ministry, we can rule out the possibility that climate ministries are established as a reaction to a significant surge in climate policies. Instead, our evidence suggests that climate ministries do have their own and tangible impact on policy outcomes, independent of the broader (previous) governmental initiatives or ambitions.

Likewise, one might contend that the observed effects are not attributable to enhanced enforcement, but rather to the signaling effect of the state’s commitment. For instance, Bayer and Aklin26 have shown that the rollout of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) impacted businesses’ behavior, even when carbon prices were insufficiently high to drive tangible changes in carbon emission levels. The authors conclude that the very establishment of a formal climate policy framework was enough to bolster the perception of the government’s resolution among businesses, prompting them to begin reducing their emissions. The same could be true for climate ministry creation. Certainly, we cannot completely discount the possibility that a portion of the emission reductions observed may stem from a reaction by the targeted groups that is entirely disconnected from the actual climate policies or their enforcement. Nevertheless, we consider the argument for improved policy implementation to be more compelling. This is for two reasons: First, if the impact were merely attributable to “signaling,” then the specificity of the term “climate” being used in isolation or in conjunction with other terms should not yield a markedly different outcome (see again our discussion on the level of “specialization” of climate ministries”). In both scenarios, the signal sent by the government—its professed priority of addressing climate concerns—is essentially the same. Second, if it were merely about signaling, with the government failing to take substantive action thereafter, we would expect to observe a more “abrupt” effect that potentially fades as citizens and businesses come to realize that the government’s intentions are not followed by concrete measures. However, what we observe is quite the contrary; the impact steadily grows stronger over time, suggesting that there is indeed “real” action underpinning these changes.

Discussion

The challenging task of addressing climate change demands careful coordination and a comprehensive transformation of existing institutional arrangements. Our research into the establishment of dedicated climate ministries offers important insights into the concrete ways in which institutional change can bolster climate action. Our empirical findings suggest that creating designed climate ministries leads to significant reductions in carbon emissions. This is pivotal, considering that a drop in carbon emissions is a direct metric reflecting the tangible impact of climate policies. This positive outcome becomes even more noteworthy when we consider that this reduction is achieved without a simultaneous increase in the number or stringency of climate policies.

The presence of a dedicated climate ministry, as indicated by our analysis, paves the way for a more coherent approach to climate action, eliminating the potential pitfalls that arise from blurred or disjointed responsibilities. By ensuring clear demarcation of responsibility and dedicating resources specifically towards climate policy issues, climate ministries enhance the effectiveness of existing climate policies. This finding refutes the notion that merely increasing policy numbers or intensifying ambitiousness is the only path forward. Instead, it underscores the importance of having a dedicated body with clear responsibilities that can steer climate action in a focused manner.

Yet, it is equally essential to recognize the limitations and nuances within this broader observation. As revealed by our supplementary analyses, mere nomenclature, or the cursory inclusion of “climate” within a ministry’s name is not enough. The real impact comes from a genuine specialization, where climate action is prioritized and not diluted amidst other responsibilities. Our study also throws light on the significance of having the right kind of institutional architecture. When climate action is situated within broader (environmental) ministries, the specificity required for targeted climate action could be compromised. Thus, while environmental concerns are undoubtedly paramount, there is a pressing need for focused attention on climate issues, given the scale and urgency of the climate crisis. In light of the findings presented, two straightforward policy recommendations can be made: First, governments should consider establishing stand-alone ministries with a sole focus on climate change. Second, optimally, these should be standalone climate ministries, free from the dilution of attention and resources that often accompanies broader environmental or multi-focus portfolios.

The formation of dedicated climate ministries and their impact on carbon emissions presents a compelling argument, revealing the importance of specialized institutional structures for effective climate action5,6,7. However, the broader “ecosystem” within which these ministries operate is characterized by inter-ministerial dynamics and coalition politics. Both these aspects can profoundly influence the effectiveness of climate ministries in practice, and thus, merit closer examination in future research. First, in any governmental structure, ministries do not operate in isolation. Their actions, decisions, and policy formulations often intersect with the mandates of other ministries. This intersection can either foster synergies or lead to competition for resources, policy dominance, or even bureaucratic turf wars27,28 Future research could further investigate how the effectiveness of climate ministries is influenced by the presence (or absence) of other ministries. Second, the distribution of ministerial portfolios among coalition partners is a strategic exercise, often reflecting the power dynamics and priorities of the involved parties. It would therefore be intriguing to explore how the influence of climate ministries varies, for instance, based on whether the ministry is led by the senior or the junior partner in a coalition. Finally, the effect of a climate ministry might depend on broader socio-economic and political characteristics. For example, our sensitivity analysis suggests that the effect of establishing a climate ministry might be stronger in richer countries with higher overall administrative capacities. The rapid diffusion of climate ministries will allow future analyses to have a closer look at factors that might serve as moderators.

In conclusion, as countries grapple with the urgent task of climate mitigation, creating dedicated climate ministries stands out as an actionable, impactful step. Coupled with robust execution, these institutional changes could become pivotal in the global battle against climate change.

Methods

Our analysis relies on panel data for 169 countries between 2000 and 2021, and a list of countries can be found in the Supplemental Material. Our data is structured in country-years. Our central independent variable is climate ministry creation. We then look at the effect of establishing a dedicated climate ministry on CO2 emissions as well as on the number, type, and design of policies.

We retrieved the ministry names (in English) and the dates of their creation from the WhoGov dataset. Although the WhoGov dataset is primarily designed to provide bibliographic details such as gender and party affiliation of cabinet members across all countries, it can be restructured to reveal the names of the organizations these cabinet members helm (Nyrup & Bramwell 2020). A ministry’s portfolio can be identified in two ways: first, by dissecting the ministry’s structure to understand the subjects its organizational units handle and, second, by referring to the given name of the ministry. Therefore, we code a country as having established a dedicated climate ministry when the word “Climate” appears in a ministry name for the first time. Moreover, we validated all the identified ministries against secondary sources, and we checked whether there were any ministries not identified by WhoGov by conducting systematic internet searches. Although a ministry can hold responsibility for a specific policy area even without its name explicitly referencing this area (for discussion, see Klüser, et al.29), the inclusion of a policy area within a ministry’s name substantially signifies its place within the ministry’s policy portfolio30. The names of ministerial portfolios and ministries are not always synonymous. For example, in New Zealand, the minister for Climate Change operates in the Ministry for the Environment. To take this into account we rerun the main analysis in the Appendix (Fig. S7) where we exclude ministries with multiple ministers.

Policy data were extracted from the Climate Policy Database18. Today, this database includes over 5000 national climate policies worldwide. The database conceives of policies as the combination of certain sectors (what is addressed?) and policy types/instruments (how is it addressed?). The included sectors encompass Agriculture and Forestry, Buildings, Electricity and Heat, General, Industry, and Transport. The array of policy instruments encompasses, among others, economic instruments, information and education, regulatory instruments, and research & development and deployment. We specifically distinguish between regulatory and market-based instruments, typically viewed as more ambitious, and other policy measures. The latter group includes initiatives related to information and education, research & development and deployment, and voluntary approaches. Data on CO2 emissions comes from the World Bank, which sourced data from the Climate Watch Historical GHG Emissions Database31.

In our analysis, we also consider a range of different time-variant variables to ensure a comprehensive examination of the relationships at hand. These variables include the annual GDP growth rate per capita, which provides a measure of the economic output per person. Data come from the World Bank31. By incorporating this variable, we account for the economic development of each country and its potential influence on the relationship being studied32. Furthermore, we include the size of the industrial sector as a share of GDP in our analysis to account for potential changes in economic structure that could affect both the policy measures taken and the emissions profile. A decrease in a country’s industry share may suggest both lower emissions and a reduced level of political protectionism towards the respective economic branches32. In addition, we account for a selection of political factors. Previous research has shown that democracies exhibit stronger commitments to mitigate climate change and are more inclined to cooperate in international treaties33,34. Here, we use a binary variable that measures whether a country was a democracy in a respective year to account for democratization processes that might affect our result. The variable codes a country as a democracy if it fulfills conditions for contestation and participation35. In addition to these variables, we also account for climate policies using the data from the Climate Policy Database when looking at CO2 emissions and vice versa, as both are likely to affect one another. By including these control variables in our analysis, we aim to enhance the robustness and accuracy of our findings by considering important economic as well as political factors that may have an impact on the relationship under scrutiny.

We use an econometric technique that leverages variation in the timing of the establishment of dedicated climate ministries. In our models, we use the approach by Imai et al. which combines matching methods with a difference-in-differences estimator17. We compare countries that have established a dedicated climate year in a respective year with those countries that have a similar pre-treatment trajectory in terms of treatment history (i.e., whether a country has had a previous climate ministry that had been closed again) and time-variant covariates. This allows us to look at the development of the effect of establishing a climate ministry over time. Formally, the average treatment effect on the treated takes the following form:

Parameter F enables us to estimate the cumulative treatment effect over time. Due to the time coverage of our data, we set F = 5. Thus, we measure the treatment effect of establishing a climate ministry for up to 5 years after. Furthermore, we adjust for treatment history up to 5 years before the introduction of a ministry by setting \(L=5\). Country \(i\) that establishes a ministry in year t is the treated unit. Put differently, \({X}_{{it}}=1\) as well as \({X}_{i,t-1}=0\). For these countries, \({Y}_{i,t+F}\left({X}_{{it}}=1,{{X}}_{i,t-1}=0,\,\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{{{\ell}}{\mathscr{=}}2}^{L}{X}_{i,t{\mathscr{-}}{{\ell}}}\right)\) is the potential outcome. Since we cannot observe the counterfactual outcome had a country not introduced a climate ministry, we look at the potential outcome of those countries that have not introduced a climate ministry in a respective year, namely:

As the introduction of climate ministries is not randomly assigned, we have to account for observed as well as unobserved confounders (\(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{k=1}^{K}({X}_{{kit}})\)). To account for time-invariant confounders, we use a difference-in-differences estimator that solely looks at changes in the dependent variable. Furthermore, we use Mahalanobis matching to ensure that we only compare countries that are similar on a set of time-varying confounders. The difference-in-differences estimator accounts for unobserved time-invariant confounders under the condition that the parallel trend assumption holds. Only comparing units during the same time periods and additionally accounting for GDP growth trajectories via the matching approach also ensure that our results are not driven by common economic chocks such as the 2007 to 2008 financial crisis.

Standard errors are computed by using the block-bootstrap procedure introduced by Imai et al.17. In contrast to standard bootstrapping, this procedure uses the weight each observation gets when matching and uses it as a conditional factor instead of recomputing it in the bootstrapping procedure.

In addition to the difference-in-differences analysis, we also run a time-series cross-sectional data analysis with carbon emissions per capita in metric tons as our dependent variable. Since we are interested in changes in carbon emissions, we include country fixed effects in our models. We use a stepwise approach to ensure that our results are not driven by covariate choices. We start by solely including the existence of a climate ministry each year plus country fixed effects. Subsequently, we add year fixed effects, our control variables, and lagged levels of CO2 emissions. We use standard OLS standard errors.

Data availability

All data used in this article are available upon request.

References

Hovi, J., Sprinz, DF., Sælen, H. & Underdal, A. The club approach: a gateway to effective climate co-operation? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 1071–1096 (2019).

Linsenmeier, M., Mohommad, A. & Schwerhoff, G. Global benefits of the international diffusion of carbon pricing policies. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 679–684 (2023).

Caballero, R. & Huber, M. State-dependent climate sensitivity in past warm climates and its implications for future climate projections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14162–14167 (2013).

Dannenberg, A., Lumkowsky, M., Carlton, E. K. & Victor, D. G. Naming and shaming as a strategy for enforcing the Paris Agreement: The role of political institutions and public concern. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, 2023 (2023).

Guy, J., Shears, E. & Meckling, J. National models of climate governance among major emitters. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 189–195 (2023).

Dubash, N. K. et al. National climate institutions complement targets and policies. Science 374, 690–693 (2021).

Mildenberger, M. The development of climate institutions in the United States. Environ. Polit. 30, 71–92 (2021).

Tosun, J. Investigating ministry names for comparative policy analysis: lessons from energy governance. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 20, 324–335 (2018).

Schmidt, N. M. Late bloomer? Agricultural policy integration and coordination patterns in climate policies. J. Eur. Public Policy 27, 893–911 (2020).

Bauer, A., Feichtinger, J. & Steurer, R. The Governance of Climate Change Adaptation in 10 OECD Countries: Challenges and Approaches. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 14, 279–304 (2012).

Boasson, E. L. National climate policy: a multi-field approach (Routledge, 2014).

von Lüpke, H., Leopold, L. & Tosun, J. Institutional coordination arrangements as elements of policy design spaces: insights from climate policy. Policy Sci. 56, 49–68 (2023).

Fernández-i-Marín, X., Knill, C. & Steinebach, Y. Studying policy design quality in comparative perspective. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 115, 931–947 (2021).

Wagner, P. M., Torney, D. & Ylä-Anttila, T. Governing a multilevel and cross-sectoral climate policy implementation network. Environ. Policy Gov. 31, 417–431 (2021).

Fransen, T. et al. Taking stock of the implementation gap in climate policy. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 752–755 (2023).

Steinebach, Y. Instrument choice, implementation structures, and the effectiveness of environmental policies: a cross-national analysis. Regul. Gov. 16, 225–242 (2022).

Imai, K., Kim, I. S. & Wang, E. H. Matching methods for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data. Am. J. Political Sci. 67, 587–605 (2023).

Nascimento, L. et al. Twenty years of climate policy: G20 coverage and gaps. Clim. Policy 22, 158–174 (2022).

Henstra, D. The tools of climate adaptation policy: analysing instruments and instrument selection. Clim. Policy 16, 496–521 (2016).

Blanchard, O., Gollier, C. & Tirole, J. The portfolio of economic policies needed to fight climate change. Annu. Rev. Econ. 15, 689–722 (2023).

Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S. & Seubert, S. Toward a comparative measure of climate policy output. Policy Stud. J. 43, 257–282 (2015).

Steinebach, Y. & Limberg, J. Implementing market mechanisms in the Paris era: the importance of bureaucratic capacity building for international climate policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 29, 1153–1168 (2022).

Hanson, J. K. & Sigman, R. Leviathan’s latent dimensions: measuring state capacity for comparative political research. J. Politics 83, 1495–1510 (2021).

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R. & Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Political Anal. 14, 63–82 (2006).

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J. & Xu, Y. How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple Tools to improve empirical practice. Political Anal. 27, 163–192 (2019).

Bayer, P. & Aklin, M. The European Union Emissions Trading System reduced CO2 emissions despite low prices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8804–8812 (2020).

Senninger, R., Finke, D. & Blom-Hansen, J. Coordination inside government administrations: Lessons from the EU Commission. Governance 34, 707–726 (2021).

Nyrup, J. & Bramwell, S. Who governs? A new global dataset on members of cabinets. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 114, 1366–1374 (2020).

Klüser, K. J. From bureaucratic capacity to legislation: how ministerial resources shape governments’ policy-making capabilities. West Eur. Polit. 46, 347–373 (2023).

Mortensen, P. B. & Green-Pedersen, C. Institutional effects of changes in political attention: explaining organizational changes in the top bureaucracy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 25, 165–189 (2015).

World Bank World. Development Indicators (WDI) (The World Bank, 2023).

Jahn, D. The politics of environmental performance (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Povitkina, M. The limits of democracy in tackling climate change. Environ. Polit. 27, 411–432 (2018).

Bättig, M. & Bernauer, T. National Institutions and Global Public Goods: are democracies more cooperative in climate change policy? Int. Organ. 63, 281–308 (2009).

Boix, C., Miller, M. & Rosato, S. A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007. Comp. Political Stud. 46, 1523–1554 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions on how to enhance our manuscript. We also extend our thanks to the participants of the Policy, Bureaucracy, and Organization (PBO) workshop in Geilo, members of the Environmental Politics and Governance (EPG) Group (online), and attendees of the Research Colloquium at the Chair of Christoph Knill at the LMU Munich for their feedback. This research was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (ACCELZ Project, Grant No. 335073) and received Småforsk funding from the Department of Political Science at the University of Oslo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., Y.S. and J.N. have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the completed version, and are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. J.L., Y.S. and J.N. have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Limberg, J., Steinebach, Y. & Nyrup, J. Dedicated climate ministries help to reduce carbon emissions. npj Clim. Action 3, 70 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-024-00147-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-024-00147-9