Abstract

With the exception of germ-line mutations in ovarian cancer susceptibility genes, genetic predictors for women destined for ovarian serous cancer cannot be identified in advance of malignancy. We recently showed that benign secretory cell outgrowths (SCOUTs) in the oviduct are increased in frequency with concurrent serous cancer and typically lack PAX2 expression (PAX2-null). The present study examined the relationship of PAX2-null SCOUTs to high-grade serous cancers by comparing oviducts from women with benign gynecologic conditions and high-grade serous cancers. PAX2-null SCOUTs were identified by immunostaining and computed as a function of ___location, frequency (F) per number of cross-sections examined, and age. Six hundred thirty-nine cross-sections from 35 serous cancers (364) and 35 controls (275) were examined. PAX2-null SCOUTs consisted of discrete linear stretches of altered epithelium ranging from cuboidal/columnar, to pseudostratified, the latter including ciliated differentiation. They were evenly distributed among proximal and fimbrial tubal sections. One hundred fourteen (F=0.31) and 45 (F=0.16) PAX2-null SCOUTs were identified in cases and controls, respectively. Mean individual case-specific frequencies for cases and controls were 0.39 and 0.14, respectively. SCOUT frequency increased significantly with age in both groups (P=0.01). However, when adjusted for age and the number of sections examined, the differences in frequency between cases and controls remained significant at P=0.006. This study supports a relationship between discrete PAX2 gene dysregulation in the oviduct and both increasing age and, more significantly, the presence of co-existing serous cancer. We propose a unique co-variable in benign oviductal epithelium—the PAX2-null SCOUT—that reflects underlying dysregulation in genes linked to serous neoplasia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Ovarian cancer affects >23 000 and kills >15 000 women each year in the United States.1 The majority of these tumors are high-grade serous cancers (‘serous cancer’). The absence of effective screening or risk prediction, coupled with the very high percentage presenting with advanced disease has resulted in a low cure rate and high mortality.2 Efforts to identify the source of serous cancers have revealed that the oviduct, particularly the fimbriated end, is responsible for a larger proportion of serous cancers than previously thought, both in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and the general population.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 A serous cancer precursor has been proposed to arise in the distal oviduct. It may begin with TP53 mutations in secretory cells, leading to a clonally derived population with altered expression of p53 in the setting of DNA damage (H2AX). This precursor, termed the ‘p53 signature,’ shares several attributes with serous cancer and has been demonstrated to exist in anatomic continuity with serous intraepithelial carcinoma, the earliest form of serous cancer.8, 9, 10 Serous intraepithelial carcinoma is the most common (∼80–85%) gynecologic malignancy detected in risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomies of women at genetic risk (BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations) and has been detected in approximately one-half of randomly selected women with advanced serous cancer.3, 7, 11 For this reason, the distal tube is now considered an important site of origin for serous cancer.

The existence of the p53 signature and its association with mutation or dysregulation of multiple genes (TP53, PAX2, HMGA2) is consistent with the disruption of multiple molecular pathways during serous carcinogenesis.12, 13 The precursor harboring these gene alterations is typically a discrete expansion of secretory cells. Recently, Chen et al14 described another secretory cell outgrowth (SCOUT) in the tube that stained strongly with BCL2 and, frequently, negative for PAX2 (PAX2-null). In contrast to the p53 signature, SCOUTs contained wild-type p53 by sequence analysis. SCOUTs were prevalent in equal frequency throughout the oviduct, and the authors concluded that molecular pathway disturbances leading to SCOUTs were not restricted to the distal tube.14

A compelling finding by Chen et al14 was the observation that SCOUTs were found in a significantly higher frequency in tubes from serous cancer patients, present in ∼30% of histologic sections of these oviducts vs <5% from women without malignancy. They concluded that the SCOUTs might signal, by their greater frequency, a greater likelihood of co-existing serous cancer.14 The purpose of this study was to further scrutinize the relationship between PAX2-null SCOUTs and serous cancers by including a more homogeneous control population, with attention to differences in age and tissue localization as potential confounders.

Materials and methods

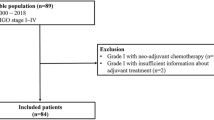

A series of consecutively identified cases from 2005 to 2010 were culled from pathology files of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Children's Hospital in Boston, MA. These studies were approved for human subjects study by their respective institutional review boards. The controls consisted of hysterectomies performed for benign disease (ie prolapse, leiomyomata). Advanced pelvic high-grade serous cancers were the cases. In both cases and controls, both fimbrial and proximal tubes were submitted for evaluation. All available sections of oviduct from each case were retrieved for PAX2 immunostaining.

Immunostaining for PAX2 was performed as previously described, reviewed by two observers (CMQ and JB) and discrepancies adjudicated by a third observer (CPC).14 The slides were scored for the absence of PAX2 (PAX2-null) in the setting of a SCOUT. Histologically, PAX2-null SCOUTs were defined as linear arrays of at least 30 consecutive cells that showed a population of predominately secretory cell phenotype, in which PAX2 was absent or conspicuously reduced in a homogenous fashion relative to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 1). Linear arrays of ciliated cells, which are typically PAX2 negative, were not counted.

(a) PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowth (H&E) occupies an entire plica in the center. (b) Note the sharp lines of demarcation between PAX2 positive and the PAX2-null epithelium along the plica (arrows). (c) At higher magnification, the stratified epithelium of the secretory cell outgrowth (lower) contrasts to the normal (upper) in the boxed area. (d) The boxed area shows loss of nuclear PAX2 staining (lower) relative to the uninvolved mucosa (upper).

Data were analyzed statistically by negative binomial regression analysis. For each slide, the number of cross-sections reviewed and total number of PAX2-null SCOUTs were recorded. Scoring was performed by two observers independently. The following were calculated: (1) frequency (F, in average number of SCOUTs per section) of PAX2-null SCOUTs in cases and controls; (2) distribution of SCOUTs in proximal and fimbrial cross-sections; (3) average frequencies of SCOUTs in cross-sections as a function of 10-year groups in cases and controls; and (4) statistical significance of frequencies of PAX2-null SCOUTs in cases and controls after correcting for age and number of sections examined. To account for age differences and the varying numbers of sections examined for each subject, the data were modeled on the assumption that the number of SCOUTs in each section follows a Poisson distribution, with Poisson rate depending on group and age, with an offset term used to account for the number of sections examined. The data were adjusted for age in the model, using 10-year groupings (26–35, 36–45, etc). The Poisson probability distribution is commonly used to model count data; it is a one-parameter distribution and it fixes the variance to be equal to the mean. As this is often overly restrictive, it may be extended by assuming variability of the Poisson parameter across subjects, which yields a negative binomial model. For comparisons as a function of patient age, the age data were stratified into 10-year groups (ie 26–35, 36–45, etc).

Results

PAX2-Null SCOUTs are Discrete Alterations in the Oviductal Mucosa Characterized by Variable Pseudostratification and Associated Ciliation

PAX2-null SCOUTs were visible by light microscopic examination and could usually be distinguished from the adjacent mucosa as a discrete population of cells ranging from cuboidal/columnar to pseudostratified, the latter showing variable cilia. Some exhibited pseudostratification and prominent cilia, suggesting that some retained the capacity for terminal (ciliated) differentiation. The loss of PAX2 staining was typically complete, or at the most equal to background cytoplasmic staining of adjacent stroma. The latter, which occurred in some staining runs, could be eliminated by further dilution of the primary antibody.

PAX2-Null SCOUTs are Evenly Distributed Between Fimbrial and Proximal Areas of the Oviduct

Two hundred sixty-five and 199 sections from cases and controls were designated specifically in the pathology reports as either fimbrial or proximal in ___location. Figure 2 graphically illustrates the differences in frequency of SCOUTs in these sections only. In all, 23% (9/39) of fimbrial and 27% (60/226) proximal sections from cases averaged a PAX2-null SCOUT in contrast to 18 (7/39) and 25% (40/160) of controls, respectively. Adjusting for subject and number of sections of each type examined, the difference in frequencies between fimbrial and proximal areas overall was not significant (P=0.24). This confirmed a prior report showing an equivalent distribution of SCOUTs between proximal and fimbrial sections.14

Graphical representation of the frequency distribution of PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowths in a subset of sections in cases and controls designated specifically as fimbrial or proximal in ___location. The differences in frequency between the two locations were not significant in either group or combined.

PAX2-Null SCOUTs are Significantly more Frequent in Oviducts of Women with Serous Cancer

PAX2-null foci of SCOUT varied in size, ranging from those meeting the minimum criteria (30 cells) up to involvement of entire plica (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the average number (frequency) of PAX2-null SCOUTs per cross-section in each group and Figures 3 and 4 are graphical displays. The overall frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs was 0.32 in cases of serous cancer and 0.16 in controls and the individual case-specific frequencies in the serous cancers and benign hysterectomies were 0.39 and 0.14 (P=0.006). In two additional control groups consisting of pediatric autopsy cases and tubal sterilizations from another study, the frequency approached zero (Figure 3).15

Graphical representation of the frequencies (in average number per cross-section examined) of PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowths in fallopian tubes from pediatric autopsies, post-partum sterilization specimens, benign hysterectomies, and serous carcinomas).15

Box-plot of the frequency distribution of PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowths in the oviducts associated with serous cancers and benign hysterectomies. The boxes denote the middle (25–75th percentile) quartile values, divided at the median with the short, horizontal line designating the mean. The upper and lower vertical lines signify the first and fourth quartiles, respectively. See Results.

PAX2-Null Foci Increase in Frequency as a Function of Age but are Independently Associated with Serous Cancers

Two key goals of this study were to determine (1) whether the increase PAX2-null SCOUTs in patients with serous cancer observed by Chen et al14 would be corroborated in a second data set and (2) whether the differences were independent of age. The latter question was prompted by the exceedingly low frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs in pediatric autopsy specimens and post-partum tubal sterilizations, two groups considerably younger on average than women undergoing surgery for benign disease and malignancies.15 We addressed these questions in a regression model that adjusted for age, as well as the number of cross-sections on the frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs by linear regression analysis. For cases and controls, each group was divided according to 10-year intervals (26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, etc) and the average frequencies for the intervals were compared (Figure 5). There were no significant differences in average frequency as a function of increasing age in either group. When both the cases and controls were combined to provide a greater number for comparison, a significant correlation was seen but was weak, with a determination coefficient of 0.064. This implies that only 6.4% of the increase in frequency could be attributed to age.

In a second approach, a negative binomial regression analysis was applied to the cases and controls to determine the impact of age in 10-year intervals on the frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs. To account for age differences and the varying numbers of sections examined. Serous cancer cases registered significantly more counts than benign controls (P=0.006), an average increase of 0.94 log counts for cases vs controls. This finding is independent of age, which was itself significantly associated with PAX2-null SCOUTs as well (P=0.01). Both analyses underscored a strong association between PAX2-null SCOUTs and serous cancers independent of age.

Discussion

We have shown previously that the distal oviduct harbors clonal expansions of secretory cells that are unique for strong immunostaining for p53, loss of TP53 function and a similarity to—and association with—high-grade serous cancer.8 These expansions, termed ‘p53 signatures’ are currently the most plausible precursor candidates to high-grade serous cancers developing in the oviduct.8, 10, 16 However, it is known that in addition to loss of TP53 function, numerous other disturbances in gene expression characterize high-grade serous cancers, and it is logical to presume that precursors contain some of these functional alterations.17, 18 One of these genes, PAX2, has been shown to be down-regulated in both high-grade müllerian (endometrioid or serous) pelvic carcinomas and in benign and neoplastic endometrium.16, 19, 20, 21 Recently, we identified a second form of SCOUT in the oviduct that exhibited normal TP53 genotype but on further analysis, frequently showed a loss or reduction of PAX2 immunostaining.14 In a comparison of serous cancers, benign controls, and benign tubes from women with germ-line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, a higher frequency of these foci appeared strongly associated with malignancy.14 However, SCOUTs were evenly distributed in the tube being no more prevalent in the fimbria than proximal segments.14, 15 From this, we concluded that SCOUTs reflected pathway disturbances that, while more prevalent in women with high-grade serous cancers, were not direct precursors to serous cancer. Nevertheless, loss of PAX2 staining was also highly prevalent in p53 signatures, secretory cell expansions with p53 mutations that are candidate precursors.8 The presence of two forms of secretory cell expansion showing PAX2 dysregulation in the oviduct underscored the need to understand the distribution of this phenomenon and its relationship to age and neoplasia.

We have recently shown that PAX2-null SCOUTs are virtually absent in oviducts from the pediatric population and oviducts from post-partum sterilizations (Table 1).15 It is important to emphasize that PAX2-null SCOUTs with normal p53 expression appear to be distributed equally in fimbrial and proximal oviductal sections, shown by Chen et al14 and confirmed in this report. Thus, the absence of PAX2-null SCOUTs in pediatric and post-partum sterilization tubal sections is significant despite the limited sampling of the tubes in these populations. Whether the near absence of PAX2-null SCOUTs in these two groups reflects a direct or indirect relationship to concurrent ovulatory cycles is unclear. Pre-pubertal and post-partum states are characterized by absent ovulation, but the same can be said for post-menopausal women, who harbor a higher frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs. The association of PAX2-null SCOUTs with age coincides with a recent report showing that the frequency of p53 signatures is also increased in older women.22 These findings suggest that increasing age—or the onset of menopause—elevates the odds that molecular perturbations will occur in the oviduct. However, this association has not been universally confirmed; a prior report by us finding minor and non-significant differences in mean age between women with and without p53 signatures.8 Moreover, it is increasingly clear that the tabulation of p53 signatures (or SCOUTs) is influenced by sampling opportunity.23 In this study, we estimated that increasing age accounted for a relatively small increase in the frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs (Figure 5). Furthermore, negative binomial regression analysis showed a strong association between PAX2-null SCOUTs and serous cancers after age was accounted for. Thus, resolving the potential role of age and hormonal influences will require further study.14

The high frequency of PAX2-null SCOUTs in 6-μm sections derived from the oviducts of women with serous cancer suggests that the oviducts of these individuals could harbor literally thousands of discrete foci with PAX2 gene dysregulation. What remains unclear is whether this widely distributed, multifocal loss of PAX2 function in the oviduct with normal TP53 expression is related to the spatially restricted loss of PAX2 staining associated with TP53 mutations in the fimbria in the form of p53 signatures and tubal intraepithelial carcinomas.14, 16 We have recently found that borderline serous tumors, which are not associated with loss of p53 function, also show an increase in PAX2-null secretory outgrowths in their oviducts and also display focal loss of PAX2 immunostaining.15 Such associations emphasize the need for more study to resolve the significance of SCOUTs in pelvic epithelial tumorigenesis. What is clear is that although they are discrete in appearance, PAX2-null SCOUTs, like p53 signatures, do not harbor a marked increase in proliferative index (Ning G, unpublished data).

The association between PAX2-null SCOUTs and ovarian cancer is intriguing in light of the link between benign mucosal proliferations and cancers in other sites, such as the colon and pancreas.24, 25 In one proposed model, PAX2-null secretory outgrowths are increased in frequency in the fallopian tubes of women with high-grade serous cancer yet are separable geographically by their TP53 mutation status, association with DNA damage and ___location (Figure 6). Further analysis of SCOUTs for these and other gene perturbations might yield new insights into the pathogenesis of serous cancer. A second and increasingly obvious avenue of investigation worthy of attention is the varied level of ciliated cell differentiation. This suggests that ‘secretory’ cell outgrowths, with their differences in ciliation, might signify different lineages derived from altered oviductal stem cells.

A schematic of discrete epithelial changes in the fallopian tube associated with dysregulation of PAX2. PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowths are widespread (green dots) but a subset with p53 mutations and evidence of DNA damage repair response (H2AX; p53 signatures) are more regionally restricted, localizing to the distal fallopian tube. The latter co-segregate with much rarer malignancies (serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas).

References

Cannistra SA . Cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1550–1559.

Partridge E, Kreimer AR, Greenlee RT, et al. Results from four rounds of ovarian cancer screening in a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:775–782.

Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol 2005;100:58–64.

Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:230–236.

Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:161–169.

Salvador S, Rempel A, Soslow RA, et al. Chromosomal instability in oviduct precursor lesions of serous carcinoma and frequent monoclonality of synchronous ovarian and oviduct mucosal serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2008;110:408–417.

Przybycin CG, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM, et al. Are all pelvic (nonuterine) serous carcinomas of tubal origin? Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1407–1416.

Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal oviduct. J Pathol 2006;211:26–35.

Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE, et al. Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1283–1289.

Shaw PA, Rouzbahman M, Pizer ES, et al. Candidate serous cancer precursors in oviduct epithelium of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Mod Pathol 2009;22:1133–1138.

Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, et al. Primary oviduct malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3985–3990.

Wei JJ, Wu J, Luan C, et al. HMGA2: a potential biomarker complement to P53 for detection of early-stage high-grade papillary serous carcinoma in oviducts. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:18–26.

Mehra K, Mehrad M, Ning G, et al. STICS, SCOUTs and p53 signatures; a new language for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2011;3:625–634.

Chen EY, Mehra K, Mehrad M, et al. Secretory cell outgrowth, PAX2 and serous carcinogenesis in the Oviduct. J Pathol 2010;222:110–116.

Laury AR, Ning G, Quick CM, et al. Fallopian tube correlates of serous borderline tumors. Am J Surg Pathol (in press).

Roh MH, Yassin Y, Miron A, et al. High-grade fimbrial-ovarian carcinomas are unified by altered p53, PTEN and PAX2 expression. Mod Pathol 2010;23:1316–1324.

Marquez RT, Baggerly KA, Patterson AP, et al. Patterns of gene expression in different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer correlate with those in normal fallopian tube, endometrium, and colon. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:6116–6126.

Bowtell DD . The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:803–808.

Chivukula M, Dabbs DJ, O’Connor S, et al. PAX 2: a novel Müllerian marker for serous papillary carcinomas to differentiate from micropapillary breast carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2009;28:570–578.

Monte NM, Webster KA, Neuberg D, et al. Joint loss of PAX2 and PTEN expression in endometrial precancers and cancer. Cancer Res 2010;70:6225–6232.

Tung CS, Mok SC, Tsang YT, et al. PAX2 expression in low malignant potential ovarian tumors and low-grade ovarian serous carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2009;22:1243–1250.

Vicus D, Shaw PA, Finch A, et al. Risk factors for non-invasive lesions of the oviduct in BRCA mutation carriers. Gynecol Oncol 2010;118:295–298.

Mehra KK, Chang MC, Folkins AK, et al. The impact of tissue block sampling on the detection of p53 signatures in fallopian tubes from women with BRCA 1 or 2 mutations (BRCA+) and controls. Mod Pathol 2010;24:152–156.

Fornasarig M, Valentini M, Poletti M, et al. Evaluation of the risk for metachronous colorectal neoplasms following intestinal polypectomy: a clinical, endoscopic and pathological study. Hepatogastroenterology 1998;45:1565–1572.

Liszka L, Pajak J, Mrowiec S, et al. Precursor lesions of early onset pancreatic cancer. Virchows Arch 2011;458:439–451.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs Ross Berkowitz, Michael Muto, Colleen Feltmate, and Neil Horowitz at Brigham and Women's Hospital and to Dr Judy Garber at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute for their cooperation and support. This work was funded by grants from the National Institute of Health RO1-GM083348 (FDM), R21 CA12468 (CPC) and a grant from the Department of Defense, W81XWH-10-1-0289 (CPC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quick, C., Ning, G., Bijron, J. et al. PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowths in the oviduct and their relationship to pelvic serous cancer. Mod Pathol 25, 449–455 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.175

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.175

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasia: the concept and its application

Modern Pathology (2017)

-

PAX2 function, regulation and targeting in fallopian tube-derived high-grade serous ovarian cancer

Oncogene (2017)

-

LEF1 is preferentially expressed in the tubal-peritoneal junctions and is a reliable marker of tubal intraepithelial lesions

Modern Pathology (2017)

-

IMP3 as a cytoplasmic biomarker for early serous tubal carcinogenesis

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2014)

-

IMP3 signatures of fallopian tube: a risk for pelvic serous cancers

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2014)