Abstract

Synthesizing isotopes located far away from the line of β-stability is the core research topic in nuclear physics. However, it remains a challenge due to their tiny production cross sections and short half-lives. Here, we report on the observation of a very neutron-deficient isotope 210Pa produced via the fusion-evaporation reaction 175Lu(40Ca, 5n)210Pa at a newly constructed China Accelerator Facility for Superheavy Elements. The measured α-particle energy of Eα = 8284(15) keV and half-life of \({T}_{1/2}=6.{0}_{-1.1}^{+1.5}\) ms of 210Pa allow us to extend the α-decay systematics and test the predictive power of theoretical models for heavy nuclei near the proton drip line. Based on its unhindered α-decay character, the spin and parity of 210Pa is proposed to be (3+), supported by the large-scale shell model and cranked shell model calculations. This isotope is discovered with substantial statics within ∼ 3 days using intensive 2 pμA beam, demonstrating the tremendous capability of the facility for the study of heavy and superheavy nuclei.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atomic nuclei are quantum many-body systems with a finite number of protons and neutrons. There are approximately 288 stable or long-lived nuclides on Earth forming a valley of stability at the center of nuclear landscape1. However, when one moves away from this valley, nuclei become unstable and short-lived radioactive, i.e., disintegrating by emitting charged particles (e.g., proton, α and β-particles) or splitting into smaller parts through spontaneous fission. Nuclear density functional theory predicts that there are about 7000 nuclides with proton numbers between Z = 2 and 120 while approximately 3365 nuclides have been identified so far1,2. Although important progress on the expanding the nuclei landscape has been made in the last decades reaching Z = 1183, the long-standing question of the limits for the existence of nuclei still remains.

At present most of our knowledge of the structure of atomic nucleus is based on the properties of nuclei close to the line of β-stability, where the theoretical calculations reproduce the experimental data well. However, nuclei far from the line of β-stability do not always follow the textbook behavior of known stable isotopes. For instance the vanishing of traditional shell closures and the emergence of new magic numbers, a central concept of nuclear structure4, were observed when going to extremes in the proton-to-neutron ratio5,6,7. Therefore, studying the decay properties of nuclei far from the line of β-stability is crucial for our understanding the nature of nuclei8.

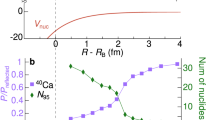

In the region ‘north-west’ of 208Pb (Z = 82, N = 126), the heaviest doubly magic nucleus, there is a vast territory of α-emitters. Alpha decay, although one of the oldest decay modes, remains an intriguing subject and has been proved as a powerful tool to identify heavy isotopes and to investigate the nuclear structure and masses of nuclei9,10,11,12,13. The obtained spectroscopic data from α decay can be used to test and modify the theoretical models for the nuclei with large Q-values and short half-lives, which is especially important for the synthesis and study of superheavy elements14. While several interesting nuclear-structure phenomena, e.g., shape coexistence and the sudden changes in deformation between neighboring nuclei are observed around the neutron-deficient lead region15,16,17, information about the nuclear structure towards higher Z nuclei close to the proton drip line is rather scarce, although some of them have been identified for a long time1. For the protactinium there are 29 known isotopes to date and the proton drip line has been already reached, with 214Pa being the first proton-unbound isotope18, albeit no proton decay has yet been observed. Prior to the present study the lightest protactinium isotope was 211Pa, which was produced in the complete-fusion reaction 181Ta(36Ar, 6n)211Pa at the gas-filled recoil separator RITU19. Based on only three correlated α-decay chains, the α-decay properties were determined to be Eα = 8320(40) keV and \({T}_{1/2}=3.{8}_{-1.4}^{+4.6}\) ms and the production cross section was measured as low as 20 pb.

Mapping the boundaries of nuclear chart in this region is exceptionally challenging owing to the tiny production cross sections and short half-lives of nuclei. Presently the heavy-ion induced fusion-evaporation reactions are used as one of the most effective methods for the production of neutron-deficient heavy nuclei in this region20,21. However, as the fission barriers of compound nuclei decrease rapidly with the increasing proton number, the production cross sections are often reduced to picobarn levels or even less, resulting in that nuclei are produced at a rate of only one nuclide every tens of days13,22. To meet the challenge connected with such low cross sections, powerful accelerators that deliver intense heavy-ion beams as well as efficient in-flight separators are needed. Recently the China Accelerator Facility for Superheavy Elements (CAFE2) that provides very intense heavy-ion beams for the production of heavy and superheavy nuclei has been constructed at the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences23,24. The schematic view of CAFE2 is shown in Fig. 1. A new gas-filled recoil separator SHANS2 (Spectrometer for Heavy Atoms and Nuclear Structure-2) was also built at the end of the beam line24. Their application allowed us to produce and identify heavy isotopes even with tiny production cross sections22,25.

In our previous work26, the excitation functions of the fusion-evaporation reaction 40Ca+175Lu have been reported. Here, we report on the observation of a previously unknown isotope 210Pa, which was synthesized in the 175Lu(40Ca, 5n)210Pa reaction at CAFE2. The measured α-decay properties of 210Pa extend the α-decay systematics in this region, and allow us to test the predictive power of theoretical models for the heavy nuclei at and beyond the proton drip line. The successful discovery of the isotope with a very low production cross section was achieved at CAFE2 using a typical beam intensity of 2 pμA within only 76 h experimental run, which illustrates the high sensitivity of CAFE2 for the production of heavy and superheavy nuclei.

Results

Primary beam of 40Ca13+ with Elab = 212 MeV was generated by a chain of machines (see Fig. 1), including an Electron Cyclotron Resonance Ion Source (ECRIS), a Radio-Frequency Quadrupole (RFQ) accelerator, and a Superconducting Continuous Wave Linear Accelerator (SC-CW-Linac). Evaporation residues (ERs) were collected and separated from the primary beam and other unwanted reaction products by a newly commissioned gas-filled recoil separator SHANS2. After passing through a gas-counter system, the ERs were finally implanted into a double-sided silicon strip detector (DSSD) surrounded by six single-sided strip detectors (SSDs) at the focal plane of the separator, where their implantation and subsequent α decays were measured.

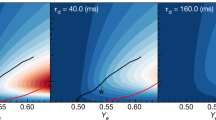

The identification of 210Pa was performed by searching for the position-time correlated α-decay chains with the help of known α-decay properties of its descendants. Figure 2a presents the energy spectrum for α particles following implanted residues in the same DSSD pixel within a time window of 30 ms. The α activities from Ac and Th isotopes, which were produced in the pxn and αxn evaporation channels, are clearly identified based on their known α-decay properties. Here, it should be noted that the presence of 213Rn and 214Fr nuclei can be explained as transfer reaction products due to the small contamination of 209Bi material (∼0.08%) in our targets. In Fig. 2b, a two-dimensional scatter plot showing the correlation between the parent and child α particles is presented. The searching time windows were 30 ms for the ER-α1 pair and 150 ms for α1-α2 pair. In the region where the parent α-particle energy is around 8.3 MeV and the child α-particle energy is around 7.8 MeV, the correlations are assigned to the decay of 210Pa, which was produced via the 5n evaporation channel.

a α particles following the implanted residues within a time window of 30 ms. Note that the isotopes of 213Rn and 214Fr were transfer products due to the small contamination of 209Bi material in our targets. b Two-dimensional scatter plot of parent and child α-particle energies for correlated ER-α1 − α2 events detected in the DSSD. The searching time windows were 30 ms for the ER-α1 pair and 150 ms for the α1-α2 pair. The decay events from 210Pa are indicated with red arrow.

Furthermore, a search for decay chains with four consecutive α decays (ER-α1-α2-α3-α4) was performed so as to identify 210Pa more reliably. Finally, 23 correlated α-decay chains were established for 210Pa and the measured α-particle energies and decay-time distributions for each chain member are displayed in Fig. 3. The α-particle energies detected by the DSSD only are marked in red in the left panel while the reconstructed events (DSSD+SSD) are marked in blue and not used to deduce the α-particle energy due to their relatively poor energy resolution. The half-lives were extracted using the maximum likelihood method described in ref. 27. In Table 1, the derived α-particle energies and half-lives for the descendants of 210Pa are compared with the literature values, which indicates a good agreement with the known ground-state decay properties. Therefore, we assign all the observed α-decay chains as originating from 210Pa. The α-particle energy and half-life of 210Pa were determined to be Eα = 8284(15) keV and T1/2 = \(6.{0}_{-1.1}^{+1.5}\) ms, respectively.

The α-particle energies detected by the DSSD only are marked in red in the left panel while the reconstructed events (DSSD+SSD) are marked in blue. The solid curves in the decay-time distributions are drawn using the deduced mean lifetime for 210Pa obtained in the present work and the literature values for the ground-states of 206Ac39, 202Fr47, and 198At50.

A thorough search for the proton-decay events of 210Pa was also conducted, but no candidate events were found.

Using a transmission efficiency of 47% of SHANS224, the production cross section for 210Pa at the center-of-target energy of 209 MeV was determined to be \({7}_{-2}^{+3}\) pb, in which the errors only represent the statistical ones estimated by the method in ref. 27.

Discussion

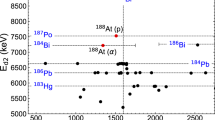

Based on the obtained results, the observed α decay of 210Pa can be assigned as the ground-state to ground-state transition. The α-particle energy and half-life allow us to extend the α-decay systematics and provide a rigorous test of nuclear models for the nuclei in this region. Figure 4 shows the systematics of experimental α-decay Qα values, partial α-decay half-lives \({T}_{1/2}^{\alpha }\), and proton separation energies Sp for the ground-states of neutron-deficient Fr, Ac, and Pa isotopes. The measured 210Pa values from this work are marked by solid triangles and the values of 203,204Ac from our recent works22,25 are also indicated. For 210Pa, a 100% α-decay branching ratio was assumed for the calculation of \({T}_{1/2}^{\alpha }\). The mass excess of 210Pa was determined to be 24355(67) keV by adding the α-decay energy and the known mass of the α particle to that of the daughter nucleus 206Ac18, and it was used to extract the Sp value of 210Pa. One can see that the measured Qα, \({T}_{1/2}^{\alpha }\), and Sp values of 210Pa fit well with the systematic trends.

a α-decay Qα values, b partial α-decay half-lives \({T}_{1/2}^{\alpha }\) of the ground-state to ground-state transitions, and (c) proton separation energies Sp for neutron-deficient Fr, Ac, and Pa isotopes as a function of neutron number. Open symbols refer to the literature values taken from refs. 18,19,22,25. The 210Pa values from this work are marked by solid triangles and the values of 203,204Ac from our recent works22,25 are also indicated. The dotted lines represented the theoretical predictions taken from refs. 28,30.

The experimental data are also compared with the selected theoretical model calculations, which are shown by the dotted lines in Fig. 4. The theoretically predicted Qα and Sp values were obtained by the WS4 global mass model with corrections of surface diffuseness effect and radial basis function28. For this macroscopic-microscopic model, the systematic improvements for the masses of unstable nuclei were achieved with the best accuracy ever found within the mean-filed approximation29. As one can see in Fig. 4a, c, the accurate description for known nuclei and predictions for 210Pa were obtained. In the present work, the measured α-decay energy Qα = 8.445(15) MeV of 210Pa was reproduced well by the predicted Qα = 8.525 MeV.

The partial α-decay half-lives \({T}_{1/2}^{\alpha }\) of Fr-Pa isotopes were calculated from the experimental Qα values according to a new Geiger-Nuttall law proposed by Ren et al.30, see Fig. 4b. In this calculation, the effects of the quantum numbers of α-core relative motion were taken into account in the Geiger-Nuttall law, which makes it valid for the ground-state α decay of heavy nuclei around N = 126 without any change of parameters. As compared in Fig. 4b, we can find a good agreement between the predicted and experimental values even if the half-lives vary up to 10 orders of magnitude along the isotopic chains.

For the proton separation energy Sp, while a good agreement between the calculations of WS4 mass model and existing experimental data can be found, the predicted value of Sp = −395 keV was slightly higher than the measured Sp = −670(123) keV of 210Pa. Another two mass models, finite-range droplet model (FRDM)31 and Hartree-Fock-BCS method (HFBCS)32, were also selected to reproduce the Sp of 210Pa. Values of Sp = −481 and −700 keV were predicted by the FRDM and HFBCS, respectively. It appears that HFBCS reproduced reasonably well the Sp value of 210Pa. As the Sp value of 210Pa is negative, it is energetically plausible for the proton emission. However, as we mentioned earlier, no proton-decay events of 210Pa were observed in the present work. To investigate further of this, we have calculated the proton-decay half-life of 210Pa using the semiempirical universal decay law33. Assuming the present Sp(210Pa) value together with l = 5 proton emission from the π h9/2 ⊗ ν f5/2 ground state of 210Pa (see the text below), the proton-decay half-life of 210Pa was calculated to be ∼ 1015 s, which is far too slow to compete with its α decay.

The obtained Sp value of 210Pa also allows us to investigate the Thomas-Ehrman effect in heavy nuclei34,35, which was explained as a reduction of Coulomb energy for proton-unbound states where the single particle wave function is pushed out of the nuclear interior. In ref. 36, the manifestation of the Thomas-Ehrman effect for 11 beyond proton drip-line nuclei between 4Li and 39Sc were claimed. For these nuclei, an average deviation between the experimental and calculated masses was found to be −576.5 keV, significantly larger than 3.4 keV for proton-bound nuclei. According to ref. 37, we adopt the liquid-drop model function of Sp = a + bA−1/3 + cA−1 to fit the Sp data of proton-bound protactinium isotopes and then check the deviations between the extrapolated fit and the measured Sp values of proton-unbound protactinium isotopes. A satisfactory agreement between the two was found and an average deviation of 48 keV was deduced, which indicates that there is no Thomas-Ehrman shift in proton-unbound protactinium isotopes up to 210Pa.

In order to gain further information on the structure of the ground state of 210Pa, the α-decay reduced width δ2 was calculated from the experimental Qα and \({T}_{1/2}^{\alpha }\) data using the method of Rasmussen38. Assuming a Δ L = 0 transition a value of δ2(210Pa) = \(2{8}_{-5}^{+7}\) keV was deduced, which is comparable to that of the neighboring even-even nucleus 210Th [(56(13)keV)]. This indicates an unhindered α decay of 210Pa, which happens almost exclusively between members of the same proton-neutron configuration in parent and child nuclei. Since the spin and parity of (3+) was proposed for the ground state of 206Ac in ref. 39, the same spin and parity of (3+) is tentatively assigned for the ground state of 210Pa.

To further justify these conclusions we have performed calculations using two theoretical approaches, namely, large-scale shell model and cranked shell model with monopole and quadrupole pairing treated by a particle-number-conserving method (PNC-CSM). In the large-scale shell model calculations, taken 164Pb as a core, six proton orbitals 0h9/2, 1f7/2, 0i13/2, 2p3/2, 1f5/2, and 2p1/2 and six neutron orbitals 0h9/2, 1f7/2, 0i13/2, 2p3/2, 1f5/2, and 2p1/2 are taken into account. The p − p, n − n, and p − n parts of two-body interactions are taken from the Kuo-Herling particle interaction40, Kuo-Herling hole interaction41, and monopole based universal interaction42 plus M3Y spin-orbit interaction43, respectively. The calculation results show that in both 206Ac and 210Pa the states have a rather pure shell-model character and there are four lowest states with spin and parity of 3+, 5+, 6+, and 7+ within only 50 keV. For both 3+ states of 206Ac and 210Pa, the proton-neutron configuration is very similar with the dominant contribution from π h9/2 ⊗ ν f5/2.

In the PNC-CSM method, the ground state and low-lying pair-broken excited states are obtained by diagonalizing the cranked shell model Hamiltonian in a truncated many-particle configuration (MPC) space, which is constructed in the proton and neutron N = 4, 5, 6 major shells. The particle number is conserved and the Pauli blocking effect can be taken into account simultaneously in the PNC-CSM calculations, by which the properties of odd-odd nucleus can be treated appropriately44,45. The results show that the ground-state spin and parity is assigned as 3+ for 210Pa, 206Ac, 202Fr, and 198At. The dominant contribution from proton and neutron configuration is πh9/2 ⊗ νf5/2 for the first three nuclei and is πh9/2 ⊗ νp3/2 for the last one. The first and second excited states for 210Pa are 5+ and 4+, with about 77 and 260 keV, respectively. One can see that both results of the two theoretical approaches are consistent with the observed unhindered nature of the α decay of 210Pa.

In conclusion, for the first time, we have produced and identified the α-emitting isotope 210Pa, which represents the most neutron-deficient protactinium isotope known so far. Good agreement between the measured ground-state decay properties and the theoretical predictions was obtained. The Thomas-Ehrman effect was investigated in the proton-unbound protactinium isotopes, but no evidence of its presence was found. Based on the analysis of α-decay width, a spin and parity of (3+) was proposed for the ground state of 210Pa, supported by the large-scale shell model and PNC-CSM calculations.

The discovery of the isotope with a rather low production cross section of \({7}_{-2}^{+3}\) pb was achieved at CAFE2 using a typical beam intensity of 2 pμA within only 76 h experimental run. This corresponds to ∼30 fb observation limit for 1 event with the same beam intensity in one-month beam time, demonstrating the high sensitivity of CAFE2. The unique capabilities of CAFE2, including very intense heavy-ion beams and high transmission efficiency of SHANS2, make it an ideal facility for the study of heavy and superheavy nuclei. Future studies at CAFE2 include, e.g., synthesis of new elements, variety of nuclear and laser spectroscopy, mass measurements, and chemistry studies of the heaviest elements, which would contribute to advancements in nuclear physics and our understanding of the fundamental properties of matter.

Methods

The ions of 40Ca13+ were produced by an Electron Cyclotron Resonance Ion Source and accelerated by a Radio-Frequency Quadrupole accelerator and a Superconducting Continuous Wave Linear accelerator to an energy of 212 MeV. The typical beam intensity of 40Ca13+ was about 2 p μ A and the total irradiation time was 76 h. Twenty arc-shaped 175Lu targets with a thickness of 0.45 mg/cm2 were mounted on a rotating wheel of 50 cm diameter and the wheel was rotated at 2000 rpm during the irradiation. The target thickness was monitored by a plastic scintillator with Si-PM (Silicon PhotoMultiplier) mounted 45 degrees with respect to the incident beam direction, which counted elastically scattered projectiles. The beam energy at the center of the target was estimated to be 209 MeV, which corresponds to the expected maximum cross section for the 5n evaporation channel according to the calculation with the HIVAP code46.

The ERs recoiled out of the target and were separated from the primary beam and other unwanted reaction products by the gas-filled recoil separator SHANS224. The separator was filled with helium gas at a pressure of 100 Pa and the magnetic rigidity of the magnets were set to be 1.596 Tm to guide the evaporation residues to the center of the focal plane with an efficiency of 47%. The ERs surviving during the flight were implanted into a 300 μm-thick double-sided silicon strip detector (DSSD) with 128 vertical and 48 horizontal 1 mm-wide strips. To detect the α particles escaped from the DSSD, six single-sided strip detectors (SSDs) with sensitive areas of 120 × 63 mm2 were mounted perpendicular to the surface of the DSSD. Each SSD has a thickness of 500 μm and is divided into eight 15 × 63 mm2 strips. The total detection efficiency of the detector array was measured to be 86(8)%. Two multiwire proportional counters were installed in front of the DSSD allowing us to distinguish the decay events from the implantation ones. Behind the DSSD, three punch-through silicon detectors were mounted for the rejection of signals produced by energetic light particles. All the silicon detectors were cooled down to −30 °C to gain a better energy resolution using an alcohol cooling system. Waveform digitizers V1724 with 100 MHz sampling from CAEN S.p.A. were used for the data acquisition.

Energy calibrations of the DSSD and SSDs were performed using a three-peak (244Cm, 241Am, and 239Pu) α source and the known peaks from 205,206Rn, 208,209Fr and 207,208Ra produced in the present reaction. The typical energy resolution for the DSSD was 40 keV (full width at half maximum, FWHM) for 6–9 MeV α particles. The total energy of an escaped α particle was reconstructed by adding the deposited energies in the DSSD and SSDs and had an energy resolution of 80–120 keV.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper. The data that generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28882703.

Code availability

The analysis codes used for the experimental data analysis are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Thoennessen, M. Discovery of Nuclides Project webpage, https://people.nscl.msu.edu/thoennes/isotopes/index.html.

Erler, J. et al. The limits of the nuclear landscape. Nature 486, 509 (2012).

Oganessian, Y. & Utyonkov, V. Superheavy nuclei from 48Ca-induced reactions. Nucl. Phys. A 944, 62 (2015).

Mayer, M. G. On closed shells in nuclei. ii. Phys. Rev. 75, 1969 (1949).

Sorlin, O. & Porquet, M.-G. Nuclear magic numbers: New features far from stability. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 61, 602 (2008).

Otsuka, T., Gade, A., Sorlin, O., Suzuki, T. & Utsuno, Y. Evolution of shell structure in exotic nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 015002 (2020).

Nowacki, F., Obertelli, A. & Poves, A. The neutron-rich edge of the nuclear landscape: Experiment and theory. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 120, 103866 (2021).

Huyse, M. The why and how of radioactive-beam research, in https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-44490-9_1The Euroschool Lectures on Physics with Exotic Beams, Vol. I edited by J., Al-Khalili and E., Roeckl pp. 1–32 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004).

Hofmann, S. & Münzenberg, G. The discovery of the heaviest elements. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 733 (2000).

Andreyev, A. N. et al. Signatures of the Z=82 shell closure in α-decay process. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 242502 (2013).

Khuyagbaatar, J. et al. New short-lived isotope 221U and the mass surface near N=126. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 242502 (2015).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. New isotope 220Np: Probing the robustness of the N=126 shell closure in neptunium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 192503 (2019).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. New α-emitting isotope 214U and abnormal enhancement of α-particle clustering in lightest uranium isotopes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 152502 (2021).

Smits, O. R., Düllmann, C. E., Indelicato, P., Nazarewicz, W. & Schwerdtfeger, P. The quest for superheavy elements and the limit of the periodic table. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 86 (2024).

Heyde, K. & Wood, J. L. Shape coexistence in atomic nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1467 (2011).

Marsh, B. A. et al. Characterization of the shape-staggering effect in mercury nuclei. Nat. Phys. 14, 1163 (2018).

Barzakh, A. et al. Large shape staggering in neutron-deficient Bi isotopes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 192501 (2021).

Wang, M., Huang, W., Kondev, F., Audi, G. & Naimi, S. The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references*. Chin. Phys. C. 45, 030003 (2021).

Auranen, K. et al. Exploring the boundaries of the nuclear landscape: α-decay properties of 211Pa. Phys. Rev. C. 102, 034305 (2020).

Vermeulen, D. et al. Cross sections for evaporation residue production near the N=126 shell closure. Z. Phys. A 318, 157 (1984).

Heßberger, F. et al. Decay properties of neutron-deficient nuclei in the region Z = 86–92. Eur. Phys. J. A 8, 521 (2000).

Wang, J. et al. α-decay properties of new neutron-deficient isotope 203Ac. Phys. Lett. B 850, 138503 (2024).

Sheng, L. et al. Ion-optical design and multiparticle tracking in 3D magnetic field of the gas-filled recoil separator SHANS2 at CAFE2. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1004, 165348 (2021).

Xu, S. et al. A gas-filled recoil separator, SHANS2, at the China Accelerator Facility for Superheavy Elements. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1050, 168113 (2023).

Huang, M. et al. α decay of the new isotope 204Ac. Phys. Lett. B 834, 137484 (2022).

Zhang, M. M. et al. Experimental cross section study of 40Ca+175Lu: Searching for new neutron-deficient Pa isotopes. Phys. Rev. C. 109, 014608 (2024).

Schmidt, K. H., Sahm, C. C., Pielenz, K. & Clerc, H. G. Some remarks on the error analysis in the case of poor statistics. Z. Phys. A 316, 19 (1984).

Wang, N., Liu, M., Wu, X. & Meng, J. Surface diffuseness correction in global mass formula. Phys. Lett. B 734, 215 (2014).

Sobiczewski, A., Litvinov, Y. & Palczewski, M. Detailed illustration of the accuracy of currently used nuclear-mass models. Data Nucl. Data Tables 119, 1 (2018).

Ren, Y. & Ren, Z. New Geiger-Nuttall law for α decay of heavy nuclei. Phys. Rev. C. 85, 044608 (2012).

Möller, P., Sierk, A. J., Ichikawa, T. & Sagawa, H. Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations: FRDM (2012). Data Nucl. Data Tables 109, 1 (2016).

Goriely, S., Tondeur, F. & Pearson, J. A Hartree–Fock nuclear mass table. Data Nucl. Data Tables 77, 311 (2001).

Qi, C., Delion, D. S., Liotta, R. J. & Wyss, R. Effects of formation properties in one-proton radioactivity. Phys. Rev. C. 85, 011303 (2012).

Thomas, R. An analysis of the energy levels of the mirror nuclei, C13 and N13. Phys. Rev. 88, 1109 (1952).

Ehrman, J. B. On the displacement of corresponding energy levels of C13 and N13. Phys. Rev. 81, 412 (1951).

Comay, E., Kelson, I. & Zidon, A. The Thomas-Ehrman shift across the proton dripline. Phys. Lett. B 210, 31 (1988).

Novikov, Y. N. et al. Mass mapping of a new area of neutron-deficient suburanium nuclides. Nucl. Phys. A 697, 92 (2002).

Rasmussen, J. O. Alpha-decay barrier penetrabilities with an exponential nuclear potential: Even-even nuclei. Phys. Rev. 113, 1593 (1959).

Eskola, K. et al. α decay of the new isotope 206Ac. Phys. Rev. C. 57, 417 (1998).

Warburton, E. K. & Brown, B. A. Appraisal of the Kuo-Herling shell-model interaction and application to A=210–212 nuclei. Phys. Rev. C. 43, 602 (1991).

Warburton, E. K. First-forbidden β decay in the lead region and mesonic enhancement of the weak axial current. Phys. Rev. C. 44, 233 (1991).

Otsuka, T. et al. Novel features of nuclear forces and shell evolution in exotic nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 012501 (2010).

Bertsch, G., Borysowicz, J., McManus, H. & Love, W. Interactions for inelastic scattering derived from realistic potentials. Nucl. Phys. A 284, 399 (1977).

Zeng, J., Jin, T. & Zhao, Z. Reduction of nuclear moment of inertia due to pairing interaction. Phys. Rev. C. 50, 1388 (1994).

He, X.-T. & Li, Y.-C. Insight into nuclear midshell structures by studying K isomers in rare-earth neutron-rich nuclei. Phys. Rev. C. 98, 064314 (2018).

Reisdorf, W. Analysis of fissionability data at high excitation energies: I. the level density problem. Z. Phys. A 300, 227 (1981).

Kalaninová, Z. et al. Decay of 201−203Ra and 200−202Fr. Phys. Rev. C. 89, 054312 (2014).

Uusitalo, J. et al. α decay studies of very neutron-deficient francium and radium isotopes. Phys. Rev. C. 71, 024306 (2005).

Enqvist, T. et al. Alpha decay properties of 200−202Fr. Z. Phys. A 354, 1 (1996).

Huyse, M. et al. Isomers in three doubly odd Fr-At-Bi α-decay chains. Phys. Rev. C. 46, 1209 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the accelerator crew of CAFE2 for providing the stable 40Ca13+ beams. This work was supported by the National Key R& D Program of China [Contract No. 2023YFA1606500 (Z.G.G. and Z.Y.Z.), No. 2024YFE0110400 (M.H.H)], the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research [Grant No. 2021B0301030006 (Z.G.G., Z.Y.Z., and H.S.X.)], the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences [Grant No. XDB34010000 (Z.G.G.)], the Gansu Key Project for Science and Technology [Grant No. 23ZDGA014 (Z.Y.Z.)], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grants No. 12105328 (M.M.Z.), No. 12475126 (L.M.), No. 12035011 (Z.Z.R.), No. 12422507 (H.B.Y.), No. 12475129 (C.X.Y.), No. 12075286 (Y.L.T), No. W2412040 (M.H.H.), No. 12475121 (X.T.H.), No. 12375118 (S.G.Z.), No. 12435008 (S.G.Z.), No. W2412043 (S.G.Z.)], the CAS Light of West China Program (2022-04) (Y.L.T.), the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (Grant No. YSBR-002) (Z.Y.Z.) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS [Grants No. 2023439 (H.B.Y), No. 2020409 (Z.Y.Z.)]. A.N.A. is grateful for financial support from the STFC and the Chinese Academy of Sciences President’s International Fellowship Initiative (Grant No. 2020VMA0017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.Z., J.G.W., L.M., Z.G.G., Z.Y.Z., M.H.H., H.B.Y., C.L.Y., Y.L.T., Y.S.W., J.Y.W., Y.H.Q., X.L.W., S.Y.X., Z.Z., X.Y.H., Z.C.L., H.Z., X.Z., G.X., L.Z., F.G., J.H.Z., L.C.S., Y.J.L., H.R.Y., L.M.D., Z.W.L., W.X.H., L.T.S., Y.H., H.S.X., Z.Z.R. and S.G.Z performed the experiment. M.M.Z., J.G.W., L.M., Z.G.G., Z.Y.Z., M.H.H. and A.N.A. performed the data analysis. C.X.Y., Y.F.N. and X.T.H. provided the theory support. M.M.Z., J.G.W., L.M., Z.G.G. and A.N.A. prepared the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript at all the stages.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Myung-Ki Cheoun, H.M. Devaraja and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M.M., Wang, J.G., Ma, L. et al. Discovery of the α-emitting isotope 210Pa. Nat Commun 16, 5003 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60047-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60047-2