Abstract

We document majority support for policies entailing global redistribution and climate mitigation. Surveys on 40,680 respondents in 20 countries show strong majority support for a global carbon price funding equal cash transfers, called the Global Climate Scheme (GCS). Through our surveys on 8,000 respondents in the USA, France, Germany, Spain and the UK, we test several hypotheses that could reconcile strong stated support with scarce occurrences in public debates. Three quarters of Europeans and half of Americans support the GCS, even as they understand its cost to them. Using several experiments, we show that the support for the GCS is sincere and that political programmes that include it are preferred to programmes that do not. We document widespread support for other globally redistributive policies, such as increased foreign aid or a wealth tax funding low-income countries. In sum, global policies are genuinely supported by majorities, even in wealthy, contributing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Major sustainability objectives could be achieved by global approaches to mitigating climate change and poverty that woud involve transfers from high- to lower-income countries1,2,3,4,5,6. In particular, global carbon pricing is widely regarded by economists as the reference climate policy, as it would efficiently correct the carbon emissions externality. Specifically, a version of global carbon pricing as a system based upon tradable permits for carbon emissions is prominently discussed in environmental economics7,8,9,10,11,12,13. It would work as follows: A cap on carbon emissions to limit global warming below 2 °C is implemented. Emissions rights compatible with the carbon budget are auctioned each year to polluting firms and fund a global basic income, alleviating extreme poverty. These emission rights would be allocated equally among human adults, yielding redistribution from richer to poorer countries. It would combine long-term effectiveness, feasibility, equity and simplicity7. We call this approach to global carbon pricing the Global Climate Scheme (GCS). Although international negotiations have not yet led to ambitious globally redistributive policies, some recent prominent attempts are that the International Maritime Organization adopted a global carbon pricing mechanism on maritime fuel; the African Union calls for a global carbon taxation regime14, the United Nations (UN) are setting up a Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation15 and the G20 seeks global cooperation on the taxation of billionaires16.

We study a key factor for implementing global policies: the support of citizens. The first piece of evidence is a global survey on 40,680 respondents from 20 high- and middle-income countries. It reveals substantial support for global climate policies and, in addition, for a global tax on the wealthiest aimed at financing low-income countries’ development. Surprisingly, even in wealthy nations that would bear the burden of such globally redistributive policies, majorities of citizens express support for them. To better understand public support for global policies in high-income countries, the main analysis of this Article is conducted with surveys among 8,000 respondents from France, Germany, Spain, the UK and the USA. The focus of the Western surveys is to study how respondents react to the key trade-off between the benefits and costs of globally redistributive climate policies. In our survey, respondents are made aware of the cost that the GCS entails for their country’s people, that is, average Westerners would incur a net loss from the policy. Our main result is that the GCS is supported by three quarters of Europeans and more than half of Americans.

Furthermore, we test the robustness of this conclusion by a wide variety of methods. First, we control for social desirability bias using a list experiment. We find no evidence that people exaggerate their support in the direct question. Second, to assess whether the support would diminish in a context that approaches real stakes, we ask respondents whether they are willing to sign a petition in favour of the GCS, after informing them that the results of the survey question will be communicated to their head of state’s office. The support is sustained in an environment that approaches real stakes. Third, we carry out conjoint analyses to neutralize experimenter demand and investigate the priority given to global policies compared with other types of policy. Conjoint analyses reveal that a political platform is more likely to be preferred if it contains the GCS or a global tax on millionaires, and that global policies rank high in the prioritization of policies. Our randomized experiments also show that a candidate would not lose vote intentions by endorsing the GCS, and might even gain up to 11 points in France. Fourth, an analysis of open-ended fields indicates that the appeal of the GCS comes from its international nature and its impacts on climate, more than on global poverty. To put our main finding in context, we also test support for other global policies and examine whether people’s values are univeralistic. Support is very strong for a global tax on millionaires (69% in the USA, 84% in Europe), and the median respondent prefers to allocate 30% of the revenues of such a tax to low-income countries. Majorities are willing to increase foreign aid, but only if some conditions are respected, such as making sure the aid is well spent and other high-income countries also increase their contribution. Questions on universalistic values, including a donation experiment, confirm the congruence of underlying values with the support for specific policies. The diverse approaches summarized also help to understand what drives support for different policies. For instance, the evidence indicates that one key reason why increasing foreign aid is not as popular as global policies lies in its unilateral nature.

Overall, our results point to strong and genuine support for global climate and redistributive policies, as our experiments confirm the stated support found in direct questions. They contribute to a body of literature on attitudes towards climate policy, which confirms that climate policy is preferred at a global level17,18,19,20, where it is more effective and fair. While 3,354 economists supported a national carbon tax financing equal cash transfers in the Wall Street Journal21, numerous surveys have shown that public support for such policy is mixed22,23,24,25,26,27. Meanwhile, the GCS— the global version of this policy—is largely supported, despite higher costs in high-income countries. In the Discussion, we offer potential explanations that could reconcile the strong support for global policies with their lack of prominence in the public debate.

Literature

International surveys have shown widespread support for costly climate action23,28. For instance, representative surveys in 125 countries covering 96% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions show that 69% of the global population express willingness to contribute 1% of their income to fight global warming29. International surveys have also uncovered near consensus that “present economic differences between rich and poor countries are too large” (overall, 78% agree and 5% disagree) in each of 29 countries30.

Yet, few prior attitudinal surveys have examined global redistributive policies. A notable exception tests the support for six variants of a global carbon tax on samples in five countries, representative along gender and age31. For a given variant, the sample size is about 167 respondents per country. They find over 80% support for any variant in India, between 50% and 65% in Australia, the UK and South Africa, and 43% to 59% in the USA, depending on the variant. Notably, the support for a global carbon tax funding an equal cash transfer for each human is close to 50% in high-income countries.

Further evidence of the popularity of global redistribution is provided by the finding that 66% of Americans support providing “financial aid and technical support to developing countries that agree to limit their greenhouse gas emissions”32. In addition, 90% of Germans want some degree of global redistribution33. Besides, in surveys conducted in Brazil, Germany, Japan, the UK and the USA, support ranges from 55% to 74% for “a global democracy including both a global government and a global parliament, directly elected by the world population, to recommend and implement policies on global issues”, and similar support is found in surveys over 17 countries34,35.

The Supplementary Information contains a broader literature review including further attitudinal surveys on global policies; prior work on attitudes towards climate burden sharing, attitudes towards foreign aid, global carbon pricing, global redistribution, basic income and global democracy.

Results

Data

We use unanalysed questions from a global survey conducted in 2021 that involved 40,680 respondents from 20 countries, representing approximately 72% of global CO2 emissions. This survey (henceforth global survey) serves as the basis for measuring stated support for various global policies worldwide, including the GCS. The questions on national policies of the global survey are analysed by Dechezleprêtre et al. (2025)23. To delve deeper into the sincerity and rationales behind support for the GCS and attitudes towards global policies, global redistribution and universalistic values, we conducted further surveys in 2023 (henceforth Western surveys). These surveys are based on a sample of 8,000 respondents from France, Germany, Spain, the UK and the USA. The European survey (Eu) comprises 3,000 respondents, while the US sample was collected in two separate waves: US1 with 3,000 respondents and US2 with 2,000 respondents. The survey questions in both the European and US surveys are almost identical (Fig. 1), except for an additional question in US2 that uses results from US1 to assess the bandwagon effect and variations in policy designs in some questions.

See also Supplementary Fig. 41 for the treatment branches.

The Western surveys ensured broad representativeness along key dimensions: gender, income, age, highest diploma and degree of urbanization. The Eu survey is also representative of its four countries in terms of population size, while the US1 and US2 surveys are representative in terms of region and ethnicity. Supplementary Tables 6 and 7 detail how our samples match population frequencies. More detail on data collection is given in the Methods. The questionnaires used in the surveys are provided in Supplementary Sections C and D.

Global support

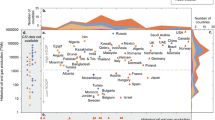

We find strong support for climate policies enacted at the global level when analysing the global survey (Fig. 2). When asked ‘At which level(s) do you think public policies to tackle climate change need to be put in place?’, 70% (in the USA) to 94% (in Japan) choose the global level. The next most popular choice is the federal or continental level, favoured by 52% of Americans and less than half of European respondents. Local policies receive the least support. This preference for climate policies implemented at the global scale is in line with earlier contributions18,19,36 and consistent with individuals’ concerns for the fairness and effectiveness of such policies, which have been identified as two of the three key determinants of support, besides self-interest22,23,37. It could also stem from a preference for conditional cooperation38, even if previous studies suggest that the support for climate policies does not depend on climate action abroad39,40,41.

The numbers represent relative support, that is, the share of ‘Somewhat support’ or ‘Strongly support’ among non-indifferent answers (in per cent, n = 40,680). Shares of indifferent answers range from 11% to 48%, with quartiles 20%, 27% and 33%. The colour blue denotes a relative majority. See Supplementary Fig. 4 for the absolute support (questions A–I). In Denmark, France and the USA, the questions with an asterisk were asked differently (c.f. question F).

Among the four global climate policies examined, three policies garner high support across all countries (Fig. 2). These policies include a global democratic assembly on climate change, a global tax on millionaires to finance low-income countries contingent on their climate action, and a global carbon budget of +2 °C divided among countries based on tradable shares (or ‘global quota’), with the allocation of country shares unspecified (see wording in Supplementary Section C). The three policies garner a majority of absolute support (that is, ‘somewhat’ or ‘strong’ support) in all countries (except in the USA for the global assembly, 48% absolute support). In high-income countries, the global quota policy obtains 64% absolute support and 84% relative support (that is, excluding ‘indifferent’ answers).

Following the support for the global quota, respondents are asked about their preferences for dividing the carbon budget among countries, as depicted in the third block of Fig. 2. Consistent with the existing literature (Supplementary Section A.1.2), an equal per capita allocation of emission rights emerges as the preferred burden-sharing principle, garnering absolute majority support in all countries and never below 84% relative support. Taking into account historical responsibilities or vulnerability to climate damages is also popular, albeit with less consensus, while grandfathering (that is, allocation of emission shares in proportion to current emissions) receives the least support in all countries.

A global carbon tax that funds a global basic income should produce the same distributional outcomes as a global tradable quota with equal per capita emission rights (to the extent that the carbon price is the same and provided that each country returns the revenues from emissions trading equally to its citizens). The support for the global carbon tax is also tested, and its redistributive effects—the average increase in expenditures along with the amount of the basic income—are specified to the respondents explicitly (see box on 'The Global Climate Scheme' and Supplementary Section D, p. 64). The support for the carbon tax is lower than for the quota (t(34,442) = −76, P < 0.001, difference −0.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.21 to −0.20), particularly in high-income countries (t(18,361) = −69, P < 0.001, difference −0.28, 95% CI −0.28 to −0.27), and there is no relative majority for the tax in Anglo-Saxon countries (consistently with the levels of support found in the only previous study that tested a global carbon tax31). Two possible reasons for this lower support are that distributive effects are specified explicitly in the case of the tax, and that people may prefer a quota, perhaps because they find it more effective than a tax to reduce emissions. The two reasons are consistent with the intermediate level of support for the GCS in the Western survey, which is based on a global quota but where the question specifies explicitly the distributive effects.

Stated support for the GCS

The Western surveys (US1, US2 and Eu) include a comprehensive exploration of citizens’ attitudes towards the GCS. We present to respondents a detailed description of the GCS and explain its distributive effects, including specific amounts at stake (as specified in the box below). Furthermore, we assess respondents’ understanding of the GCS with incentivized questions to test their comprehension of the expected financial outcome for typical individuals in high-income countries (loss) and the poorest individuals globally (gain), followed by the provision of correct answers (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

For comparison, the same approach is applied to a national redistribution (NR) scheme targeting top incomes with the aim of financing cash transfers to all adults, calibrated to offset the monetary loss of the GCS for the median emitter in their country. We evaluate respondents’ understanding that the richest would lose and the typical fellow citizens would gain from that policy. Subsequently, we summarize both schemes to enhance respondents’ recall. In addition, we present a final incentivized comprehension question and provide the expected answer that the combined GCS and NR would result in no net gain or loss for a typical fellow citizen. Finally, respondents are directly asked to express their support for the GCS and NR using a simple yes/no question.

Our main result is that stated support for the GCS is 54% in the USA and 76% in Europe, while the support for NR is very similar: 56% and 73%, respectively (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Supplementary Section F examines the sociodemographic determinants of support for the GCS as well as the beliefs correlated with the support for a global tax on GHG financing a global basic income. The strongest correlates are political leaning, trust in the government and perceptions that climate policies are effective at reducing emissions or in one’s self-interest.

Percentage of somewhat or strong support, after excluding indifferent answers; *except for GCS: percentage of ‘yes’ in a ‘yes/no’ question, preferred share: percentage of answers ≥30%, and foreign aid: percentage of unconditional or conditional increase rather than decrease or stable aid. Shares of indifferent answers range from 10% to 40%, with quartiles 19%, 25% and 32% (Supplementary Section D, questions 20, 36, 43, 44 and 45; see Supplementary Fig. 26 for the absolute support).

Finding majority support for the GCS motivates the subsequent analysis of robustness and sincerity.

Robustness and sincerity of support for the GCS

We use several methods to assess the sincerity of the support for the GCS: a list experiment, a real-stake petition, conjoint analyses and an exercise involving the prioritization of policies. All methods suggest that the support is either completely sincere, or the share of insincere answers is limited.

List experiment

By asking how many policies within a list respondents support and varying the list among respondents, a list experiment allows identifying the tacit support for a policy of interest. For example, a first subsample faces the list of policies A, B and C, while a second subsample faces the list A, B, C and GCS. We do not need to know which policies each respondent supports to estimate the average (tacit) support for the GCS; we simply need to compute the difference in the average number of supported policies between the two random subsamples42. In our case, as shown in Table 1, the tacit support for the GCS measured through the list experiment is not significantly lower than the direct stated support. Hence, we do not find a social desirability bias in our study.

Petition

We ask respondents whether they are willing to sign a petition in support of either the GCS or the NR policy. We inform them that the petition results will be sent to the head of state’s office, highlighting the proportion of fellow citizens endorsing the respective scheme. Even when framed as a petition that might have real stakes, both policies continue to receive majority support. In the USA, we find no significant difference between the support expressed in the petitions question and the simple questions (GCS: t(3,044) = 1.0, P = 0.297, difference −0.02, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.02; NR: t(2,952) = 0.3, P = 0.760, difference −0.01, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.03). In Europe, the petition leads to a comparable lower support for both the GCS, at −7 percentage points (p.p.) (t(3,018) = 4.4, P < 0.001, difference −0.07, 95% CI −0.10 to −0.04]) and NR, at −4 p.p. (t(2,953) = 2.6, P = 0.008, difference −0.04, 95% CI −0.08 to −0.01). While some European respondents are unwilling to sign a petition for policies they are expected to support, this phenomenon is not specific to the GCS, and the overall willingness to sign a petition remains strong, with 69% expressing support for the GCS and 67% for NR.

Conjoint analyses

To assess the public support for the GCS in conjunction with other policies, we conduct a series of conjoint analyses. We ask respondents to make five choices between pairs of political platforms. Each choice is intended to test a different hypothesis about support for the GCS in relation to other policies or voting intentions.

The first conjoint analysis suggests that the GCS is supported independently of being complemented by the NR scheme and a national climate policy (C). The second analysis indicates majority support for the GCS and for C, which are seen as neither complement nor substitute (Methods). A minor share of respondents like a national climate policy and dislike a global one, but as many people prefer a global rather than a national policy. Besides, there is no evidence that implementing NR would increase the support for the GCS. In the third analysis, we present two random branches of the sample with hypothetical progressive and conservative platforms that differ only by the presence (or not) of the GCS in the progressive platform. Table 2 shows that a progressive candidate would not significantly lose voting share by endorsing the GCS in any country, and may even gain 11 p.p. in voting intention in France. Our last two analyses make respondents choose between two random platforms. In Europe, respondents are prompted to imagine that a left or centre-left coalition will win the next election and asked what platform they would prefer that coalition to have campaigned on. In the USA, the question is framed as a hypothetical duel in a Democratic primary, and asked only to non-Republicans (n = 2,218), that is, the respondents who declare as political affiliation Democrat, Independent, Non-Affiliated or Other.

In the fourth analysis, a policy (or an absence of policy) is randomly drawn for each platform in each of five categories: economic issues, societal issues, climate policy, tax system and foreign policy (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 3). In the UK, Germany and France, a platform is about 9–13 p.p. more likely to be preferred if it includes the GCS rather than no foreign policy. This effect is between 1 p.p. and 4 p.p. and no longer significant in the USA (among non-Republicans) and in Spain. Moreover, a platform that includes a global tax on millionaires rather than no foreign policy is 5–13 p.p. more likely to be preferred in all countries (the effect is significant and at least 9 p.p. in all countries but Spain). Similarly, a global democratic assembly on climate change has a significant effect of 8–12 p.p. in the USA (among non-Republicans), France and Germany (this echoes earlier findings on global democracy34). These effects are large, and not far from the effects of the policies most influential on the platforms, which range between 15 p.p. and 18 p.p. in most countries (27 p.p. in Spain), and all relate to improved public services (in particular healthcare, housing and education).

The fifth analysis draws random platforms similarly, except that candidate A’s platform always contains the GCS while B’s includes no foreign policy. In this case, A is chosen by 60% of Europeans and 58% of non-Republican Americans (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Overall, taking the USA as an example, our conjoint analyses indicate that a candidate at the Democratic primary would have more chances to obtain the nomination by endorsing the GCS, and this endorsement would not penalize her or him at the presidential election.

Prioritization

Towards the end of the survey, we ask respondents to allocate 100 points among six randomly selected policies from the previous conjoint analyses, using sliders. The instruction was to distribute the points on the basis of their level of support, with a higher allocation indicating greater support for a policy. As a result, the average support across policies is 16.67 points. In each country, the GCS ranks in the middle of all policies or above, with an average number of points from 15.4 in the USA to 22.9 in Germany.

Interestingly, in Germany, the most prioritized policy is the global tax on millionaires, while the GCS is the second most prioritized policy. The global tax on millionaires consistently ranks no lower than fifth position (out of 15 or 17 policies) in every country, garnering an average of 18.9 points in Spain to 22.9 points in Germany.

Pros and cons

We survey respondents to gather their perspectives on the pros and cons of the GCS, randomly utilizing an open-ended or a closed question. In the closed question format, respondents tend to consider every argument as important in determining their support or opposition to the GCS (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The open-ended question provides more insights into what people associate with the GCS when prompted to think about it. Analysing keywords in the responses (automatically translated into English), the most frequently mentioned topics are the international dimension and the environment, each appearing in approximately one-quarter of the answers (Supplementary Fig. 12). This is followed by discussions on the effects of the GCS on poverty and prices, each mentioned by about one-tenth of the respondents. We also manually classified each answer into different categories (Supplementary Fig. 11). This exercise confirms the findings from the automatic search: the environmental benefit of the GCS is the most commonly discussed topic, while obstacles to implementation or agreement on the proposal are relatively infrequently mentioned.

In the US2 survey, we divided the sample into four random branches. Two branches were presented the pros and cons questions (either in open or closed format) before being asked about their support for the GCS or NR. Another branch received information on the actual level of support for the GCS and NR (estimated in US1, see box 'Second-order Beliefs'), and one control group received none of these treatments. The objective of the pros and cons treatment was to mimic a campaign effect, which refers to the shift in opinion resulting from media coverage of the proposal43,44. To conservatively estimate the effect of a (potentially negative) campaign, we intentionally included more cons (6) than pros (3). Interestingly, the support for the GCS decreased by 11 p.p. (t(1,996) = −3.5, P < 0.001, difference −0.11, 95% CI −0.17 to −0.05) after respondents viewed a list of its pros and cons. Notably, the support also decreased by 7 p.p. (t(1,996) = −2.3, P = 0.020, difference −0.07, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.01) after respondents were asked to consider the pros and cons in an open-ended question. Despite some significant effects of pondering the pros and cons, approximately half of the Americans express support for the GCS across all treatment branches (Extended Data Table 1). Although support remains significant, these results suggest that the public success of the GCS would be sensitive to the content of the debate about it, and oriented by the discourse adopted by interest groups.

Stated support for global redistribution

We also assess support for a range of other international policies (Fig. 3) as well as unilateral foreign aid.

International policies

Most policies garner relative majority support in each country, with two exceptions: the ‘cancellation of low-income countries’ public debt’ and ‘a maximum wealth limit’ for each individual (Fig. 3). There is relative majority support for the latter in Europe but not in the USA, despite the cap being set at US$10 billion in the USA compared with €/£100 million in Europe. Notably, climate-related policies enjoy strong popularity, with ‘high-income countries funding renewable energy in low-income countries’ receiving absolute majority support in all countries surveyed. In addition, relative support for loss and damages compensation, as approved in principle at the international climate negotiations in 2022 (‘COP27’), ranges from 55% (USA) to 81% (Spain). Consistent with the results of the global survey, a ‘tax on millionaires of all countries to finance low-income countries’ garners relative support of 69% in the USA and 84% in Europe, only 3 p.p. lower than a national millionaires tax overall (t(4,243) = −2.2, P = 0.028, difference −0.03, 95% CI −0.05 to 0). In random subsamples, we also inquire about respondents’ preferences regarding the redistribution of revenues from a global tax on individual wealth exceeding US$5 million, after providing information on the revenue raised by such a tax in their country compared with low-income countries. We ask certain respondents (n = 1,283) what percentage of the global tax revenues should be pooled to finance low-income countries. In each country, at least 88% of respondents indicate a positive amount, with an average of one-third (Extended Data Fig. 4). To other respondents (n = 1,233), we inquire whether they would prefer each country to retain all the revenues it collects or that half of the revenues be pooled to finance low-income countries. Approximately half of the respondents opt to allocate half of the tax revenues to low-income countries, consistently with the other variant of the question.

Foreign aid

We provide respondents with information about the actual amount ‘spent on foreign aid to reduce poverty in low-income countries’ relative to their country’s government spending and gross domestic product. Less than 16% of respondents state that their country’s foreign aid should be reduced, while 62% express support for increasing it, including 17% who support an unconditional increase (Extended Data Fig. 5). Among the 45% who think aid should be increased under certain conditions, we subsequently ask them to specify the conditions they deem necessary (Extended Data Fig. 6). The three most commonly selected conditions are that ‘we can be sure the aid reaches people in need and money is not diverted’ (73% chose this condition), ‘recipient countries comply with climate targets and human rights’ (67%) and ‘other high-income countries also increase their foreign aid’ (48%). Meanwhile, respondents who do not wish to increase their country’s foreign aid primarily justify their view by prioritizing the well-being of their fellow citizens or by perceiving each country as responsible for its own fate (Extended Data Fig. 7). In response to an open-ended question regarding measures high-income countries should take to fight extreme poverty, a large majority of Americans expressed that more help is needed (Supplementary Fig. 39). The most commonly suggested form of aid is financial support, closely followed by investments in education.

We also inquire about the perceived amount of foreign aid. Consistent with prior research (Supplementary Section A.1.3), most people overestimate the actual amount of foreign aid (Supplementary Fig. 18). We then elicit respondents’ preferred amount of foreign aid, after randomly presenting them with either the actual amount or no information. Most of the respondents who learn the actual amount choose a bracket at least as high as the actual one, and most of those without the information choose a bracket at least as high as the perceived one (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). Finally, we ask a last question to the respondents who received the information. To those who prefer an increase of foreign aid, we ask how they would finance it: by far, the preferred source of funding is higher taxes on the wealthiest (Supplementary Fig. 23). To those who prefer a reduction, we ask how they would use the funds becoming available: in every country, more people choose higher spending on education or healthcare rather than lower taxes (Supplementary Fig. 24).

Universalistic values

We ask broad questions on people’s values to assess whether their core values are consistent with support for specific policies. When we ask respondents which group they defend when they vote, 20% choose ‘sentient beings (humans and animals)’, 22% choose ‘humans’, 33% select their ‘fellow citizens’ (or ‘Europeans’), 15% choose ‘My family and myself’ and the remaining 9% choose another group (mainly ‘My State or region’ or ‘People sharing my culture or religion’). Notably, a majority of left-wing voters choose humans or sentient beings.

Answers to this and other broad value questions are consistent with half of Americans and three quarters of Europeans supporting global policies like the GCS: people are as much willing to make a donation to poor Africans than to poor fellow citizens in a lottery experiment (except for Americans who voted for Trump or did not vote), most respondents find that global poverty and climate change are bigger problems than national inequality, and most respondents wish that their diplomats take into account global justice (see Methods for details).

Discussion

In our analysis, we have uncovered strong and genuine support for global redistributive policies.

We conclude by providing hypotheses to reconcile the scarcity of global policies in the public debate with our findings that they would be widely accepted. The first two are variations of pluralistic ignorance, and the last three represent complementary explanations.

First, there may be pluralistic ignorance among policymakers regarding universalistic values, support for the GCS or the electoral advantage of endorsing it. Second, citizens or policymakers may believe that globally redistributive policies are politically infeasible in some key (potentially foreign) countries such as the USA. Third, political discourse centrally happens at the national level, shaped by national media and institutions such as the voting system. National framing by political voices may create biases and suppress universalistic values. Fourth, many individuals, including policymakers, may be unaware of specific proposals or may perceive global redistributive policies as ill-defined or technically infeasible, ultimately dismissing them as unrealistic. Fifth, just as policy is disproportionately influenced by the economic elites45,46,47, public debate may be shaped by the wealthiest, who have vested interests in preventing global redistribution.

Uncovering evidence to support the above hypotheses could shift the perceived boundaries of political realism on this issue. Their confirmation would further support the conclusion that there exists substantial public support for global policies addressing climate change and global inequality, even in high-income countries.

Methods

Preregistration

The project is approved by Economics and Business Ethics Committee at the University of Amsterdam (EB-1113) and was preregistered in the Open Science Foundation registry on 10 January 2023 (osf.io/fy6gd). The study did not deviate from the registration: the questionnaires and the hypotheses tests used are the same as the ones given ex ante. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents, randomized treatment branches were unkown to the respondents, and our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. Respondents were compensated with gift certificates for a value of €1 after participation. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes match those reported in similar publications17,18,19,22,23.

Data collection

The article utilizes two sets of surveys (with blinding): the global survey and the Western surveys. The global surveys consist of two US surveys, US1 and US2, and one European survey, Eu. The global survey was conducted from March 2021 to March 2022 on 40,680 respondents from 20 countries (with 1,465–2,488 respondents per country). US1 collected responses from 3,000 respondents between January and March 2023, while US2 gathered data from 2,000 respondents between March and April 2023. Eu included 3,000 respondents and was conducted from February to March 2023. We used the survey companies Dynata and Bilendi. To ensure representative samples, we used stratified quotas based on gender, age (5 brackets), income (4), region (4), education level (3) and ethnicity (3) for the USA. We also incorporated survey weights throughout the analysis to account for any remaining imbalances. These weights were constructed using the quota variables as well as the degree of urbanization, and trimmed between 0.25 and 4. Stratified quotas followed by reweighting is the usual method to reduce selection bias from opt-in online panels, when better sampling methods (such as compulsory participation of random dwellings) are unavailable48. By applying weights, the results are fully representative of the respective countries along the above-mentioned dimensions. Results at the European level apply different weights which ensure representativeness of the combined four European countries. Supplementary Section G shows how our samples compare with actual population frequencies. They match the actual frequencies, except for some imbalances in specific quota demographics—such as gender in the UK (43% of women instead of 50%) or urbanity in Spain (15% rural instead of 26%)—that are corrected through our survey weights, and in the US vote (which does not affect our results, as shown by the results reweighted by vote in the ‘Support for the GCS’ section below). Supplementary Section I shows that the treatment branches are balanced. Supplementary Section J runs placebo tests of the effects of each treatment on unrelated outcomes. We do not find effects of earlier treatments on unrelated outcomes arriving later in the survey.

Data quality

The median duration is 28 min for the global survey, 14 min for US1, 11 min for US2 and 20 min for Eu. To ensure the best possible data quality, we exclude 14% inattentive respondents who fail an attention test or rush through the survey (that is, answer in less than 11.5 min in the global survey, 4 min in US1 or US2, and 6 min in Eu). Indeed, responses of excluded respondents may be unreliable. Supplementary Section K shows that our results are unchanged when including inattentive respondents. At the end of the survey, we ask whether respondents thought that our survey was politically biased and offer to provide some feedback. Sixty-nine per cent of the respondents found the survey unbiased. Twenty-four per cent found it left-wing biased, and 8% found it right-wing biased.

Statistical tests

All t-tests are two-tailed and without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Table 2 and Extended Data Table 3 report 95% CIs.

Questionnaires and raw results

The raw results are reported in Supplementary Section B, while the surveys’ structures and questionnaires are given in Supplementary Sections C and D. Details on the other questions of the global survey, analysed by Dechezleprêtre et al. (2025), can be found in the appendix of that paper23. Country-specific raw results are also available online (US, EU, FR, DE, ES and UK).

Incentives

To encourage accurate and truthful responses, several questions of the Western surveys use incentives. For each of the three comprehension questions that follow the policy descriptions, we randomly select and reward three respondents who provide correct answers with a US$50 gift certificate. Similarly, for questions involving estimating support shares for the GCS and NR, three respondents with the closest guesses to the actual values receive a US$50 gift certificate. In the donation lottery question, we randomly select one respondent and split the US$100 prize between the NGO GiveDirectly and the winner according to the winner’s choice. In total, our incentives scheme distributes gift certificates (and donations) for a value of US$850. Finally, respondents have an incentive to answer truthfully to the petition question, as they are aware that the results for that question (the share of respondents supporting the policy) will be transmitted to the office of their head of state.

Absolute versus relative support

In most questions, support or opposition for a policy is asked using a 5-point Likert scale, with compulsory response and ‘Indifferent’ as the middle option. We call absolute support the share of ‘Somewhat’ or ‘Strong support’. We generally favour the notion of relative support, which reports the share of support after excluding ‘Indifferent’ answers. Indeed, the relative support is better suited to assess whether there are more people in favour versus against a policy.

Support for the GCS

The 95% CIs are 52.4% to 56.0% in the USA and 74.2% to 77.2% in Europe. The average support is computed with survey weights, using weights based on quota variables, which exclude vote. Another method to reweigh the raw results involves running a regression of the support for the GCS on sociodemographic characteristics (including vote) and multiplying each coefficient by the population frequencies. This alternative approach yields similar figures: 76% in Europe and 52% or 53% in the USA (depending on whether individuals who did not disclose their vote are classified as non-voters or excluded). The average support among voters is 54% in the USA, with 74% support among Biden voters versus 26% among Trump voters (Supplementary Fig. 40).

Although the level of support for the GCS is significantly lower in swing states (at 51%) that are key to win US elections, the electoral effect of endorsing the GCS remains non-significantly different from zero (at +1.2 p.p.) in these states. Note that we define swing states as the eight states with less than 5 p.p. margin of victory in the 2020 election (MI, NV, PA, WI, AZ, GA, NC and FL). The results are unchanged if we use the 3 p.p. threshold (that excludes FL) instead.

List experiment

List experiments have been used to reveal social desirability bias, silencing either racism in the Southern USA49 or opposition to the invasion of Ukraine in Russia50. In our case, the question reads: “Beware, this question is quite unusual. Among the policies below, how many do you support?” The list of policies randomly varies across respondents and includes a subset of GCS, NR, C (‘Coal exit’ in the USA, ‘Thermal insulation plan’ in Europe) and O (‘Marriage only for opposite-sex couples’ in the USA, ‘Death penalty for major crimes’ in Europe). There are four branches: GCS/NR/C/O, GCS/C/O, NR/C/O and C/O. To estimate the tacit average support for the GCS and NR, we regress the number of supported policies on indicators that the list includes GCS and NR. We utilize the difference-in-means estimator, and CIs are computed using Monte Carlo simulation with the R package ‘list’42.

Petition

The respondent is randomly assigned a branch where the petition relates to the GCS or the NR scheme. The question reads: “Would you be willing to sign a petition for the [Global climate / National redistribution] scheme?

As soon as the survey is complete, we will send the results to [the U.S. President’s office], informing him what share of [American] people are willing to endorse the [Global climate / National redistribution] scheme. (You will NOT be asked to sign, only your answer here is required and remains anonymous.)”.

Paired weighted t-tests are conducted to test the equality in support for a policy among respondents who were questioned about the policy in the petition.

Conjoint analyses

The first conjoint analysis suggests that the GCS is supported independently of being complemented by the NR scheme and a national climate policy (‘Coal exit’ in the USA, ‘Thermal insulation plan’ in Europe, denoted C). Indeed, 55% of US respondents and 74% of European ones prefer the combination of C, NR and the GCS to the combination of C and NR alone, indicating similar support for the GCS conditional on NR and C than for the GCS alone (Supplementary Fig. 8).

In the second conjoint analysis, results from the first branch show that the support for the GCS conditional on NR, at 55% in the USA (n = 757) and 77% in Europe (n = 746), is not significantly different from the support for the GCS alone. This suggests that rejection of the GCS is not driven by the cost of the policy on oneself. The second branch indicates that the GCS, C or their combination are all similarly supported. This branch shows that the support for C conditional on NR is somewhat higher than the support for the GCS, at 62% in the USA (n = 751) and 84% in Europe (n = 747). However, the third one shows no significant preference for C compared with GCS (both conditional on NR), neither in Europe, where GCS is preferred by 52% (n = 741) nor in the USA, where C is preferred by 53% (n = 721). The fourth branch shows that 55% in the USA (n = 771) and 77% in Europe (n = 766) prefer the combination of C, NR and the GCS to NR alone.

The effects reported in the fourth analysis are the average marginal component effects51. The policies studied are progressive policies prominent in the country. Except for the category foreign policy, which features the GCS 42% of the time, they are drawn uniformly.

The results from the fourth and fifth analyses, suggesting an electoral advantage for candidates who support global policies, relate to the finding by Ghassim (2020) that 12% of Germans shift their voting intention from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and Christian Democratic Union (CDU)/Christian Social Union (CSU) to the Greens and the Left when they are told that the latter parties support global democracy34.

Prioritization

The prioritization allows inferring individual-level preferences for one policy over another, including their intensity. This somewhat differs from a conjoint analysis, which only allows inferring individual-level preferences for one platform over another or collective-level preferences for one policy over another. Also, by comparing platforms, conjoint analyses may be subject to interaction effects between policies of a platform (which can be seen as complementary, substitute or antagonistic), while the prioritization frames the policies as independent.

This question sheds light on a potential discrepancy between the policy priorities of the public and those enacted by legislators. For instance, while the European Union and California have enacted plans to phase out new combustion-engine cars by 2035, the proposal to ‘ban the sale of new combustion-engine cars by 2030’ emerged as one of the three least prioritized policies in each country, with an average allocation of 7.8 points in France to 11.4 points in the UK.

Open-ended question on the GCS

Around one in four respondents explicitly cites pros or cons. Few individuals explicitly express support or opposition, and misunderstandings are rare. Only 11% of the responses are empty or express a lack of opinion, although one-quarter are unclassifiable due to the rarity, nonsensical nature or irrelevance of the conveyed idea.

Pros and cons

In the closed question, the least important aspect was the negative impact on their household, with 60% in Europe (n = 1,505) and 75% in the USA (n = 493) finding it important. The most important elements differ between Europe and the USA. In Europe, the key factors are the GCS’s potential to limit climate change and reduce poverty in low-income countries, both deemed important by 85% of respondents. In the USA, having sufficient information about the scheme ranks highest at 89%, followed by its potential to foster global cooperation at 82%.

Surprisingly, the support for NR also decreased by 7 p.p. following the closed question about the GCS. This suggests that some individuals may lack attention and confuse the two policies, or that contemplating the pros and cons alters the mood of some people, moving them away from their initial positive impression.

Universalistic values

When asked what their country’s diplomats should defend in international climate negotiations, only 11% prefer their country’s ‘interests, even if it goes against global justice’. By contrast, 30% prefer global justice (with or without consideration of national interests), and the bulk of respondents (38%) prefer their country’s ‘interests, to the extent it respects global justice’.

Furthermore, when we ask respondents to assess the extent to which climate change, global poverty and inequality in their country are problems, climate change is generally seen as the most important problem (with a mean score of 0.58 after recoding answers between −2 and 2). This is followed by global poverty (0.40) and national inequality (0.35).

Finally, we conduct a lottery experiment. Respondents were automatically enrolled in a lottery with a US$100 prize and had to choose the proportion of the prize they would keep for themselves versus give to a person living in poverty. The charity donation is directed either to an African individual or a fellow citizen, depending on the respondent’s random assignment. In Europe, we observe no significant variation in the willingness to donate based on the recipient’s origin (in line with an earlier study52). In the USA, the donations to Africans are 3 p.p. lower, but the slightly lower donations to Africans are driven entirely by Trump voters and non-voters (Extended Data Table 2).

Global wealth tax estimates

A 2% tax on net wealth exceeding US$5 million would annually raise US$816 billion, leaving 99.9% of the world population untaxed. More specifically, it would collect €5 billion in Spain, €16 billion in France, £20 billion in the UK, €44 billion in Germany, US$430 billion in the USA and US$1 billion collectively in all low-income countries (28 countries, home to 700 million people). These figures come from Kappeler et al. (2021)53 (for European countries) and the World Inequality Database wealth tax simulator (https://wid.world/world-wealth-tax-simulator/; for the USA and low-income countries)54.

Design choices

As global survey results indicated strong support for global redistributive policies worldwide, we conducted our Western surveys to further investigate the surprisingly high support. Among the eight largest high-income countries, we selected the five ones with a relatively low level of support for global redistributive policies as observed in the global survey. We also focus on the GCS as its costs are less concentrated on the very rich, compared with other global redistributive policies, so we expected lower (or less genuine) support. By selecting countries that would lose from global redistribution, are less supportive than others and are focusing on less consensual policies, we aimed at conservatively assessing the level of support of world citizens for global redistribution.

We split the US survey into two waves to test the effect on the support of providing the information on the actual support, and merged the Eu survey in one wave to get larger sample sizes and more power in the analyses.

To select the policies tested, we spanned three key areas for global redistribution: climate change, inequality and global governance. We selected policies that are either on the agenda of international negotiations (international transfers for mitigation; adaptation; or loss and damages; cancellation of public debt; reform of voting rights at the UN or International Monetary Fund; global wealth tax) or advocated by prominent non-governmental organizations or scholars (global asset registry55; limits on wealth56,57; democratic climate governance58; global minimum wage59; fair trade60; carbon pricing6; increased foreign aid61).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data as well as figures of the Article are available via GitHub at github.com/bixiou/international_attitudes_toward_global_policies. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The Article’s replication requires R and RStudio (R 4.3.1, RStudio 2024.04.1 were used). All code is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11202245 (ref. 62) and via GitHub at github.com/bixiou/international_attitudes_toward_global_policies.

References

Budolfson, M. et al. Climate action with revenue recycling has benefits for poverty, inequality and well-being. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 1111–1116 (2021).

Franks, M., Lessmann, K., Jakob, M., Steckel, JanChristoph & Edenhofer, O. Mobilizing domestic resources for the Agenda 2030 via carbon pricing. Nat. Sustain. 1, 350–357 (2018).

Dennig, F., Budolfson, M. B., Fleurbaey, M., Siebert, A. & Socolow, R. H. Inequality, climate impacts on the future poor, and carbon prices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15827–15832 (2015).

Soergel, B. et al. Combining ambitious climate policies with efforts to eradicate poverty. Nat. Commun. 12, 2342 (2021).

Bauer, N. et al. Quantification of an efficiency–sovereignty trade-off in climate policy. Nature 588, 261–266 (2020).

Cramton, P. C., MacKay, D. J. C. & Ockenfels, A. Global Carbon Pricing: The Path to Climate Cooperation (MIT Press, 2017).

Grubb, M. The greenhouse effect: negotiating targets. Int. Affairs 66, 67–89 (1990).

Hoel, M. Carbon Taxes: An International Tax or Harmonized Domestic Taxes (CICERO, 1991); https://pub.cicero.oslo.no/cicero-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/192280/CICERO_Working_Paper_1991-01.pdf?sequence=1

Agarwal, A. & Narain, S. Global Warming in an Unequal World: A Case of Environmental Colonialism (India Centre for Science and Environment, 1991); https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199498734.003.0005

Bertram, G. Tradeable emission permits and the control of greenhouse gases. J. Dev. Stud. 28, 423–446 (1992).

Baer, P. et al. Equity and greenhouse gas responsibility. Science 289, 2287–2287 (2000).

Jamieson, D. Climate Change and Global Environmental Justice (MIT Press, 2001); https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1789.003.0012

Blanchard, O. & Tirole, J. Major Future Economic Challenges 444 (République Française, 2021).

The African Leaders Nairobi Declaration on Climate Change and Call to Action (African Union, 2023); https://media.africaclimatesummit.org/NAIROBI+Declaration+FURTHER+edited+060923+EN+920AM.pdf

Promotion of inclusive and effective international tax cooperation at the United Nations: resolution adopted by the General Assembly. United Nations Digital Library https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4032838?v=pdf (2023).

The Rio de Janeiro G20 Ministerial Declaration on International Tax Cooperation (G20 Brazil, 2024); https://www.gov.br/fazenda/pt-br/assuntos/g20/declaracoes/1-g20-ministerial-declaration-international-taxation-cooperation.pdf

International Social Survey Programme: Environment III (ISSP, 2010); https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13271

Beiser-McGrath, L. F. & Bernauer, T. Could revenue recycling make effective carbon taxation politically feasible? Sci. Adv. 5, eaax3323 (2019).

Sivonen, J. Attitudes toward global and national climate policies in Finland—the significance of climate change risk perception and urban/rural-domicile. GeoJournal https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10750-0 (2022),

Meilland, A., Kervinio, Y. & Méjean, Aurélie International Climate Justice: what the people think. Environ. Resour. Econ. 88, 225–247 (2025).

Economist’s statement on carbon dividends. The Wall Street Journal https://www.clcouncil.org/media/EconomistsStatement.pdf (2019).

Douenne, T. & Fabre, A. Yellow vests, pessimistic beliefs, and carbon tax aversion. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 14, 81–110 (2022).

Dechezleprêtre, A. et al. Fighting climate change: international attitudes toward climate policies. Am. Econ. Rev. 115, 1258–1300 (2025).

Carattini, S., Carvalho, M. & Fankhauser, S. Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Change 9, e531 (2018).

Maestre-Andrés, S., Drews, S. & van den Bergh, J. Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: a review of the literature. Clim. Policy 19, 1186–1204 (2019).

Mildenberger, M., Lachapelle, E., Harrison, K. & Stadelmann-Steffen, I. Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 141–147 (2022).

Sommer, S., Mattauch, L. & Pahle, M. Supporting carbon taxes: the role of fairness. Ecol. Econ. 195, 107359 (2022).

Leiserowitz, A., Carman, J. & Rosenthal, S. International Public Opinion on Climate Change (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2022); https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/international-public-opinion-on-climate-change-2022a.pdf

Andre, P., Boneva, T., Chopra, F. & Falk, A. Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 253–259 (2024).

International Social Survey Programme ISSP 2019 – Social Inequality V. (ISSP, 2019); https://www.gesis.org/en/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/social-inequality/2019

Carattini, S., Kallbekken, S. & Orlov, A. How to win public support for a global carbon tax. Nature 565, 289 (2019).

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S. & Kotcher, J. Public Support for International Climate Action (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2021); https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/public-support-international-climate-action-september-2021.pdf

Fehr, D., Mollerstrom, J. & Perez-Truglia, R. Your place in the world: relative income and global inequality. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 14, 232–268 (2022).

Ghassim, F. Who on Earth Wants Global Democracy—and Why (Not)? A Theoretical and Experimental Study of International Public Opinion. PhD thesis, Univ. Oxford (2020); https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:5d63ad08-7e5d-4287-8d0f-9f5eab58d38d

Ghassim, F. & Pauli, M. Who on Earth wants a world government, what kind, and why? An international survey experiment. Int. Stud. Quart. 68, sqae105 (2024).

Bechtel, M. M. & Scheve, K. F. Mass support for global climate agreements depends on institutional design. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13763–13768 (2013).

Klenert, D. et al. Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 669–677 (2018).

Barrett, S. Self-enforcing international environmental agreements. Oxford Econ. Papers 46, 878–894 (1994).

Aklin, Michaël & Mildenberger, M. Prisoners of the wrong dilemma: why distributive conflict, not collective action, characterizes the politics of climate change. Global Environ. Polit. 20, 4–27 (2020).

Tingley, D. & Tomz, M. Conditional cooperation and climate change. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47, 344–368 (2014).

Stern, N. & Stiglitz, J. E. Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices (Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, 2017); https://static1.squarespace.com/static/54ff9c5ce4b0a53decccfb4c/t/59b7f2409f8dce5316811916/1505227332748/CarbonPricing_FullReport.pdf

Imai, K. Multivariate regression analysis for the item count technique. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 106, 407–416 (2011).

Gustafson, A. et al. The development of partisan polarization over the Green New Deal. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 940–944 (2019).

Anderson, S., Marinescu, I. & Shor, B. Can Pigou at the polls stop us melting the poles? J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 10, 903–945 (2023).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. Defeating Kyoto: the Conservative movement’s impact on U.S. climate change policy. Social Problems 50, 348–373 (2003).

Gilens, M. & Page, B. I. Testing theories of American politics: elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Polit. 12, 564–581 (2014).

Persson, M. & Sundell, A. The rich have a slight edge: evidence from comparative data on income-based inequality in policy congruence. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 54, 514–525 (2024).

Scherpenzeel, A. C. in Social and Behavioral Research and the Internet (eds Das, M., Ester, P. & Kaczmirek, L.) Ch. 5 (Routledge, 2010).

Kuklinski, J. H., Cobb, M. D. & Gilens, M. Racial attitudes and the ‘New South’. J. Polit. 59, 323–349 (1997).

Chapkovski, P. & Schaub, M. Solid support or secret dissent? A list experiment on preference falsification during the Russian war against Ukraine. Res. Polit. 9, 20531680221108328 (2022).

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J. & Yamamoto, T. Causal inference in conjoint analysis: understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit. Anal. 22, 1–30 (2014).

Cappelen, A. W., Moene, K. O., Sørensen, ErikØ. & Tungodden, B. Needs versus entitlements—an international fairness experiment. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 11, 574–598 (2013).

Kapeller, J., Leitch, S. & Wildauer, R. A European Wealth Tax (FEPS, 2021); https://feps-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/publications/a%20european%20wealth%20tax_policy%20study.pdf

Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E. & Zucman, G. World Inequality Report 2022 (World Inequality Lab, 2022); https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2023/03/D_FINAL_WIL_RIM_RAPPORT_2303.pdf

A roadmap for a global asset registry (ICRICT, 2020); https://www.icrict.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/GAR.pdf

Robeyns, I. Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth (Astra House, (2024).

Piketty, T. A Brief History of Equality (Belknap Press, 2022).

Dryzek, J. S. & Stevenson, H. Global democracy and earth system governance. Ecol. Econ. 70, 1865–1874 (2011).

Palley, T. I. From Financial Crisis to Stagnation: The Destruction of Shared Prosperity and the Role of Economics 1st edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Hickel, J. The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions (Heinemann, 2017).

Leaving No One Behind: Time for Implementation (CONCORD, 2019); https://concordeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CONCORD_AidWatch_Report_2019_web.pdf

Fabre, A., Douenne, T. & Mattauch, L. bixiou/international_attitudes_toward_global_policies: 0.1. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11202245 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from A Sustainable Future (ASF) at the University of Amsterdam, and TU Berlin. L.M. also thanks the Robert Bosch Foundation. A.F. received funding from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-24-CE03-7110). We thank A. Dechezleprêtre, T. Kruse, B. Planterose, A. Sanchez Chico and S. Stantcheva for their inputs for the project. We thank A. Meilland for feedback. We are grateful to R. Wildauer for providing estimates on wealth tax revenues.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F. collected and analysed the data, and drafted the questionnaire and the paper. T.D. and L.M. substantially revised the questionnaire and paper, and contributed to the conception and redaction.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.F. declares that he also serves as treasurer of Global Redistribution Advocates. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Farsan Ghassim and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Preferences for various policies in political platforms.

Preferences for various policies in political platform in the UK. Effects of the presence of a policy (rather than none from this ___domain) in a random platform on the likelihood that it is preferred to another random platform. (See non-translated versions in Suppl. Figure ED1; Question 29).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Influence of the GCS on preferred platform.

Influence of the GCS on preferred platform: Preference for a random platform A that contains the Global Climate Scheme rather than a platform B that does not (in percent). (Question 30; in the U.S., asked only to non-Republicans).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Beliefs about support for the GCS and NR.

Beliefs regarding the support for the GCS and NR (Questions 21 and 23).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Preferred share of wealth tax for low-income countries.

Percent of global wealth tax that should finance low-income countries (mean). ‘Imagine a wealth tax on households with net worth above [$]5 million, enacted in all countries around the world. (…) What percentage should be pooled to finance low-income countries (instead of retained in the country’s national budget)?’ (Question 36).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Attitudes on the evolution of foreign aid.

Attitudes regarding the evolution of [own country] foreign aid. (Question 45).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Conditions at which foreign aid should be increased.

Conditions at which foreign aid should be increased (in percent). [Asked to those who wish an increase of foreign aid at some conditions.] (Question 46).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Reasons why foreign aid should not be increased.

Reasons why foreign aid should not be increased (in percent). [Asked to those who wish a decrease or stability of foreign aid.] (Question 47).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Section A. Literature review. Supplementary Section B. Raw results. Supplementary Section C. Questionnaire of the global survey (section on global policies). Supplementary Section D. Questionnaire of the Western surveys. Supplementary Section E. Net gains from the GCS. Supplementary Section F. Determinants of support. Supplementary Section G. Representativeness of the surveys. Supplementary Section H. Attrition analysis. Supplementary Section I. Balance analysis. Supplementary Section J. Placebo tests. Supplementary Section K. Main results on the extended sample. Supplementary Section L. Effect of questionnaire framing. This includes Supplementary Figs. 1–44 and Supplementary Tables 1–20.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for supplementary figures.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2, 3 and Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1–7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Table 1

LaTeX table.

Source Data Extended Data Table 2

LaTeX table.

Source Data Extended Data Table 3

LaTeX table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fabre, A., Douenne, T. & Mattauch, L. Majority support for global redistributive and climate policies. Nat Hum Behav (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02175-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02175-9