Abstract

Skipping breakfast is highly prevalent but it is not clear whether breakfast frequency is associated with metabolic syndrome in young adults. We aimed to assess the association between breakfast frequency and metabolic syndrome in Korean young adults. This cross-sectional study was based on health check-up data of university students aged 18–39 years between 2016 and 2018. Participants were stratified into three groups by breakfast frequency (non-skipper, skipper 1–3 days/week, skipper 4–7 days/week). Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of metabolic syndrome. Out of 12,302 participants, 56.8% skipped breakfast at least 4 days/week. Metabolic syndrome prevalence was higher in those skipping breakfast for 4 or more days/week compared to non-skipper. (3.1% vs 1.7%) In the age- and sex-adjusted model, individuals skipping breakfast for 4–7 days per week had a higher OR of metabolic syndrome (OR 1.73, 95% CI 1.21–2.49) compared to non-skipper. Although this association became insignificant (OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.99–2.23) after a fully adjusted multivariable model, trends of positive association between frequency of breakfast skipping and metabolic syndrome was significant (P for trend = 0.038). Frequent breakfast skipping was associated with higher odds of metabolic syndrome in young adults. Further longitudinal studies in the long term are needed to understand the association of meal patterns with metabolic syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past, breakfast, the very first meal after the longest fasts has been regarded as the most important meal of the day in terms of body metabolism and circadian rhythm1. As modern lifestyle is moving away from regular meals, skipping breakfast is increasingly a common meal pattern in the current society2. According to Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (2013–2018), 43.6% of participants reported eating breakfast less than 5 days/week3. In particular, more young adults (62.1%) did not have regular breakfast compared with middle-aged adults (33.9%).

Several previous studies reported that skipping breakfast has been associated with unfavorable health outcomes such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension4,5,6. For example, breakfast skipping was associated with higher glycemic responses after lunch compared to when breakfast was consumed in healthy young men7. A recent meta-analysis reported that skipping breakfast was associated with an increased risk of hypertension (hazard ratio = 1.20, 95% CI 1.08–1.33)8. This association was consistently observed across countries, study design, and definition of breakfast skippers. An Australian longitudinal study reported long-term detrimental effects of skipping breakfast during childhood (9–15 years old) on cardio-metabolic health later in adulthood (26–36 years old)9. A larger waist circumference and higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels in adulthood was noted among those who skipped breakfast in childhood. In addition, skipping breakfast was associated with higher calorie ingestion later in the evening10 and less optimal nutrient intake11, which may impact metabolic parameters.

Based on Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (2016–2018), the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 23% among Korean adults aged ≥ 19 years. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in men over 30 years of age has sharply increased12. A number of studies have demonstrated significant positive associations between skipping breakfast and metabolic syndrome3,6,13,14, while other studies found opposite association between skipping breakfast and metabolic syndrome15. However, some studies did not consider diet quality3,14,15 and other meal patterns (binge eating or irregularity of meal eating)6,13. Most of previous studies encompassed broad age groups without focusing on young adults. Early adulthood is a critical period of life transition, including leaving the parental home for further education or marriage, which may disrupt an individual’s pre-existing habits and make changes in diet and dietary behaviors16. Moreover, adopting and maintaining healthy lifestyle such as healthy diet in young adulthood could be linked to a lower risk of subsequent cardiovascular diseases in middle age17.

Therefore, investigating the association between skipping breakfast and prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in young adults can add evidence on the importance of healthy meal patterns in young adulthood. In this study, we primarily aimed to evaluate the association between skipping breakfast and metabolic syndrome in young adults. Additionally, we evaluated the association between general meal patterns and metabolic syndrome.

Materials and methods

Study population

We used health check-up data of 15,381 Seoul National University students, including undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral students, from 2016 through 2018. All students were eligible to voluntarily have health check-up for free once a year, and the health screening included a self-reported questionnaire (health behavior), anthropometric measurements (height, weight, and waist circumference), and laboratory tests18. We excluded participants who (1) were under 18 years or over 40 years of age (n = 137), (2) declined to participate in the study (n = 638), (3) were taking medication for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia (n = 45), (4) were foreigners (n = 1094), (5) were pregnant (n = 19), or (6) had incomplete information (n = 1146). Ultimately, a total of 12,302 participants were included in this study. All individuals provided informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University (IRB number, C-1304–062-481). Research involving human research participants must have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Anthropometric and laboratory measurements

Weight and height were measured with participants in light clothing on the day of health check-up. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m2). Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the last rib and the top of the iliac crest. Blood pressure (BP) measurements were taken with the participant in a sitting position using an automatic BP measurement system after a rest period of at least 5 min. Blood samples were taken after at least 12 h of fasting.

Definition of metabolic syndrome

The definition of metabolic syndrome was taken from the modified National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines19. Subjects who met three or more of the following criteria were diagnosed with metabolic syndrome: (1) central obesity (waist circumference ≥ 90 cm for men or ≥ 85 cm for women); (2) hypertriglyceridemia with fasting plasma triglyceride levels ≥ 150 mg/dL; (3) decreased levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) with HDL-C levels < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women; (4) hypertension with systolic or diastolic BP ≥ 130/85 mmHg; and (5) hyperglycemia with fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL.

Assessment of breakfast eating, meal patterns and dietary intake

Using a self-administered questionnaire, participants were asked how often, on average, they consumed breakfast during the past year: “How often do you eat breakfast?” According to the answers, the participants were then categorized into three groups: having breakfast for 7 days per week (non-skipper), 4–6 days per week (skipper for 1–3 days), and 0–3 days per week (skipper for 4–7 days).

Using the question “How often do you overeat or binge?”, we divided participants into three groups based on frequency of binge eating per week: less than once per week (e.g., 2–3 times per month), 1–2 times per week, and ≥ 3 times per week.

To assess meal frequency per day, we categorized the participants into two groups, using the question “How many meals do you usually eat a day?”: regular (3 meals per day) and irregular (< 3 meals per day).

Overall meal pattern was defined by combination of three variables: breakfast frequency per week (> 3 days per week or ≤ 3 days per week), binge eating per week (< 3 times per week or ≥ 3 times per week), and meal frequency per day (3 meals per day or < 3 meals per day on average). An “unhealthy” meal pattern was defined if an individual had all the bad eating patterns; “fair” was defined if an individual had 1 or 2 bad eating patterns; and “healthy” was defined if a participant had no bad eating patterns. For example, someone had an unhealthy meal pattern if they had 0–3 days with breakfast per week, ≥ 3 times of binge eating per week, and < 3 meals per day.

We also evaluated dietary intake of various foods by asking consumption frequency of fruits, vegetables, milk and dairy products, high-fat meat, processed meat, and sugared beverages (< once a week, 1–4 times a week, ≥ 5 times a week).

Other variables

Alcohol consumption was classified into non-drinker, moderate drinker, and heavy drinker based on self-questionnaires. Moderate drinking was defined as consuming 14 or less standard drinks per week in men and 7 or less standard drinks per week in women, and heavy drinking was defined as more than these amounts (1 standard drink = 12 g of alcohol)20. Smoking status was categorized into never, ex-smoker, and current smoker based on self-questionnaires. Physical activity levels were evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and total physical activity levels (metabolic equivalent [MET]-min/week) were categorized into low (< 600 MET-min/week), moderate (600–2999 MET-min/week), and high (≥ 3000 MET-min/week) physical activity21.

Statistical analysis

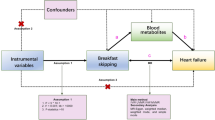

Data were expressed as the mean with standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables or as number with percentages for categorical variables. χ2 and the analysis of variance for categorical and continuous variables were used to compare general characteristics of the study population by breakfast consumption status. Logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of metabolic syndrome, with adjustment for various lifestyle and dietary factors. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex, and model 2 was adjusted for alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical activity, and BMI in addition to the covariates of model 1. Model 3 was adjusted for dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, milk and dairy products, high-fat meat, processed meat, and sugared beverages in addition to the covariates of model 2. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata ver. 16.0 for Windows (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of study population

Table 1 shows general characteristic differences across the three groups by breakfast frequency. The mean age was 24.0 ± 3.9 years. Breakfast skippers for 4–7 days/week tended to be older (24.1 years), male (55.9%), heavy drinkers (18.3%), current smokers (9.4%), and physically inactive (19.5%). The prevalence of obesity was higher in breakfast skippers for 4–7 days/week than non-skippers (16.2% vs. 13.7%). The participants who had binge eating for 3 times or more per week (7.8%) and irregular meal (86.5%) were more prevalent among those who skipped breakfast for 4–7 days/week than other groups. Non-skippers more frequently consumed brown rice, multigrain rice, beans, fruits, vegetables, milk and dairy products, egg, and coffee, and less frequently consumed bread/toast, pizza, hamburger or sandwich, rice cake/Tteokbokki, instant noodles or cup ramen, and sugared beverages (Supplementary Table 1).

Prevalence of abnormal metabolic parameter by breakfast consumption status

The mean value or prevalence of abnormal metabolic parameters are presented in Table 2. Each component of metabolic syndrome as well as hyperuricemia were more prevalent among participants skipping breakfast more frequently. Participants who frequently skipped breakfast for 4–7 days/week were more likely to have metabolic syndrome compared with non-skipper (3.1% vs. 1.7%; p < 0.001).

Association between breakfast consumption status and metabolic syndrome

The associations of breakfast consumption with metabolic syndrome and its components are shown in Table 3. In model 2, frequent breakfast skipping for 4–7 days/week was associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.09–2.36) compared to non-breakfast skipping. After additional adjustment for dietary intake in model 3, the association between frequent breakfast skipping for 4–7 days/week and metabolic syndrome was no longer significant (OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.99–2.33). However, there was a significant positive trend of the association between frequency of skipping breakfast and metabolic syndrome (P trend = 0.038). Among components of metabolic syndrome, breakfast skipper for 4–7 days/week had higher OR of high BP than non-skipper (OR: 1.34, 95% CI 1.09–1.65). The association between frequency of skipping breakfast and metabolic syndrome was consistent with main results when we applied to International Diabetes Federation- and World Health Organization-defined metabolic syndrome (Supplementary Table 2).

In stratification analyses by sex and physical activity, there was no significant interaction with skipping breakfast. (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Association between overall meal patterns and metabolic syndrome

Table 4 shows the association between overall meal patterns and metabolic syndrome. The ORs of metabolic syndrome increased as the group had unhealthier meal patterns compared to the group with a healthy meal pattern (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.02–3.19 for unhealthy; OR 1.55, 95% CI 0.90–2.66 for fair meal pattern, P for trend = 0.055).

In the case of binge eating, the OR of metabolic syndrome increased as the frequency of binge eating per week increased, but there was no statistical significance when fully adjusted (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.87–1.49 for 1–2 times of binge eating/week; OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.80–1.74 for ≥ 3 times of binge eating/week) (Supplementary Table 5). Compared to the group who had three meals per day, the OR of metabolic syndrome increased in the case of irregular meals, with marginal statistical significance when fully adjusted (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.97–1.64, p = 0.084 for irregular meals per day) (Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study among Korean young adults, we found a significant positive trend between breakfast skipping frequency and metabolic syndrome (P for trend = 0.038) and its components, especially high BP. Overall unhealthy meal pattern (defined by combination of breakfast skipping, binge eating, and irregular meal) was associated with higher odds of metabolic syndrome compared with healthy meal pattern.

Prior studies found similar results that skipping breakfast was associated with poorer cardio-metabolic health22. A recent meta-analysis based on observational studies reported that individuals having breakfast 3 times/week or more had lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, low LDL-C, and metabolic syndrome22. In a longitudinal study of Health Professionals Follow-up study (26,902 men with 16 years of follow-up) reported that those who skipped breakfast had a 27% higher risk of coronary heart disease compared with non-skippers23.

Several biological mechanisms underlying the positive association between skipping breakfast and metabolic syndrome could be suggested. First, skipping breakfast can impair insulin sensitivity. In a randomized crossover trial among healthy women, skipping breakfast impaired postprandial insulin sensitivity24. After skipping breakfast, the curve of serum insulin responses rose, whereas it fell significantly after eating breakfast. The ‘second-meal phenomenon’ could be related to impaired insulin sensitivity after breakfast skipping, which means prior meal can influence glycemic responses to a subsequent meal7. Plasma glucose after lunch rose less when breakfast was taken via suppressed free fatty acids and muscle glycogen syntheses25. Second, elevated insulin levels related to breakfast skipping can cause weight gain. A prospective cohort study in the US reported that eating breakfast was associated with lower risk of weight gain after 10 years of follow-up26. Third, insulin stimulates hydroxy methyl glutaryl (HMG) Co-A reductase, one of the rate-limiting enzymes in cholesterol syntheses by increasing rates of transcription27. Thus, skipping breakfast might induce higher LDL-C, which leads to atherosclerosis and eventually increases cardiometabolic risk9.

On the other hand, skipping breakfast can cause unhealthy eating habits at lunch or dinner. Individuals frequently skipping breakfast tended to eat a large amount at once during the rest of the day28. In a randomized controlled trial among obese people, those with morning fasting compared to having breakfast tended to have compensate calories throughout the rest of the day29. In addition, individuals who skipped breakfast rated higher appetite and hunger, less fullness, and increased ghrelin levels than those who consumed breakfast30,31. These changes in eating patterns can be related to overeating resulting in weight gain and insulin resistance.

In our study, breakfast skippers showed low overall diet quality; they were more likely to consume fast foods and foods containing high simple sugars but less likely to consume foods with high dietary fiber and micronutrients such as fruits and vegetables. Several prior studies reported that breakfast skippers consumed a significantly higher proportion of energy from fat32. A study using the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data demonstrated that Healthy Eating Index was higher in young adults who consumed breakfast than breakfast skippers33. In our study, we adjusted for various established risk factors, including dietary intake of various healthy and unhealthy foods, as confounding factors. Association between breakfast skipping and metabolic syndrome was attenuated by adjusting for dietary intake of in model 3. Thus, we assumed that dietary quality acts as one of the meaningful causal factor in the relationship between the frequency of breakfast and metabolic syndrome. Moreover, skipping breakfast may partially be correlated with unhealthy behaviors including smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, and low physical activity, although we adjusted for these factors in our analyses.

We found that overall unhealthy meal patterns such as binge eating and having irregular meal were associated with metabolic syndrome, which was in line with prior studies. Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health study suggested that binge eating was associated with increased odds of metabolic syndrome (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.44–1.75) as well as its components (hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia) through weight gain34. Having irregular meal was associated with insulin insensitivity by disturbing regular circadian variations of insulin secretion35.

Of the metabolic syndrome components, skipping breakfast was prominently associated with high BP. An experimental study in women aged 18–45 years (n = 65) found that breakfast skippers had higher circulating cortisol than breakfast eaters through stress-independent hyperactivity in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis36. Increased cortisol levels were found as a contributing factor to the development of hypertension (hazard ratio 1.23, 95% CI 1.04–1.44)37, which was stronger among younger individuals with a significant age interaction.

This study has some limitations. First, since the current study was cross-sectional, a causal relationship between breakfast frequency and metabolic syndrome could not be definitively established. Second, calorie intake was unknown due to a lack of information about the serving size of each food item. Third, our results are limited in generalizability to other ages or social groups because our study was performed among young university students. In addition, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was low (2.6%) in our study. This can be attributed to the specific characteristics of our participants, who are highly educated young adults with a higher socio-economic status. Lastly, the information on meal patterns and dietary intake were obtained using self-reported questionnaire. Thus, there could exist inaccurate recall of their dietary behaviors.

In conclusion, higher frequency of skipping breakfast was positively associated with metabolic syndrome and its components (especially high BP). Our findings indicate that eating breakfast might be an important factor to reduce risk of metabolic syndrome in young adults. Further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm this association.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data and if requested, it can be anonymized and provided.

References

Gibney, M. J. et al. Breakfast in human nutrition: The International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10050559 (2018).

Lazzeri, G. et al. Trends from 2002 to 2010 in Daily breakfast consumption and its socio-demographic correlates in adolescents across 31 countries participating in the HBSC study. PLoS ONE 11, e0151052. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151052 (2016).

Heo, J., Choi, W. J., Ham, S., Kang, S. K. & Lee, W. Association between breakfast skipping and metabolic outcomes by sex, age, and work status stratification. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 18, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-020-00526-z (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Skipping breakfast is associated with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 14, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2019.12.002 (2020).

Ballon, A., Neuenschwander, M. & Schlesinger, S. Breakfast skipping is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Nutr. 149, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxy194 (2019).

Odegaard, A. O. et al. Breakfast frequency and development of metabolic risk. Diabetes Care 36, 3100–3106. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0316 (2013).

Ogata, H. et al. Association between breakfast skipping and postprandial hyperglycaemia after lunch in healthy young individuals. Br. J. Nutr. 122, 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114519001235 (2019).

Li, Z., Li, H., Xu, Q. & Long, Y. Skipping breakfast is associated with hypertension in adults: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Hypertens. 2022, 7245223. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7245223 (2022).

Smith, K. J. et al. Skipping breakfast: Longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 92, 1316–1325. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.30101 (2010).

Sievert, K. et al. Effect of breakfast on weight and energy intake: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 364, l42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l42 (2019).

Nicklas, T. A., Myers, L., Reger, C., Beech, B. & Berenson, G. S. Impact of breakfast consumption on nutritional adequacy of the diets of young adults in Bogalusa, Louisiana: Ethnic and gender contrasts. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 98, 1432–1438. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00325-3 (1998).

Huh, J. H., Kang, D. R., Kim, J. Y. & Koh, K. K. Metabolic syndrome fact sheet 2021: Executive report. Cardiometab. Syndr. J. 1, 125–134 (2021).

Katsuura-Kamano, S. et al. Association of skipping breakfast and short sleep duration with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the general Japanese population: Baseline data from the Japan Multi-Institutional Collaborative cohort study. Prev. Med. Rep. 24, 101613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101613 (2021).

Chung, S. J., Lee, Y., Lee, S. & Choi, K. Breakfast skipping and breakfast type are associated with daily nutrient intakes and metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Nutr. Res. Pract. 9, 288–295. https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2015.9.3.288 (2015).

Jung, J., Kim, A. S., Ko, H. J., Choi, H. I. & Hong, H. E. Association between Breakfast Skipping and the Metabolic Syndrome: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017. Medicina (Kaunas) https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina56080396 (2020).

Winpenny, E. M. et al. Changes in diet through adolescence and early adulthood: Longitudinal trajectories and association with key life transitions. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 15, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0719-8 (2018).

Liu, K. et al. Healthy lifestyle through young adulthood and the presence of low cardiovascular disease risk profile in middle age: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation 125, 996–1004. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060681 (2012).

Joh, H. K., Lim, C. S. & Cho, B. Lifestyle and dietary factors associated with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in Korean young adults. J. Korean Med. Sci. 30, 1110–1120. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.8.1110 (2015).

Kim, B. Y. et al. 2020 Korean society for the study of obesity guidelines for the management of obesity in Korea. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 30, 81–92. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes21022 (2021).

Drinking levels defined. NIAAA Alcohol & Your Health website. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed 1 December 2022.

Chun, M. Y. Validity and reliability of Korean version of international physical activity questionnaire short form in the elderly. Korean J. Fam. Med. 33, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.3.144 (2012).

Li, Z. H., Xu, L., Dai, R., Li, L. J. & Wang, H. J. Effects of regular breakfast habits on metabolic and cardiovascular diseases: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 100, e27629. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027629 (2021).

Cahill, L. E. et al. Prospective study of breakfast eating and incident coronary heart disease in a cohort of male US health professionals. Circulation 128, 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001474 (2013).

Farshchi, H. R., Taylor, M. A. & Macdonald, I. A. Deleterious effects of omitting breakfast on insulin sensitivity and fasting lipid profiles in healthy lean women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn.81.2.388 (2005).

Jovanovic, A. et al. The second-meal phenomenon is associated with enhanced muscle glycogen storage in humans. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 117, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20080542 (2009).

van der Heijden, A. A., Hu, F. B., Rimm, E. B. & van Dam, R. M. A prospective study of breakfast consumption and weight gain among U.S. men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15, 2463–2469. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.292 (2007).

Ness, G. C. & Chambers, C. M. Feedback and hormonal regulation of hepatic 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase: The concept of cholesterol buffering capacity. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 224, 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22359.x (2000).

de Castro, J. M. The time of day of food intake influences overall intake in humans. J. Nutr. 134, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/134.1.104 (2004).

Chowdhury, E. A. et al. The causal role of breakfast in energy balance and health: A randomized controlled trial in obese adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 747–756. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.122044 (2016).

Kral, T. V., Whiteford, L. M., Heo, M. & Faith, M. S. Effects of eating breakfast compared with skipping breakfast on ratings of appetite and intake at subsequent meals in 8- to 10-y-old children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93, 284–291. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.000505 (2011).

Gwin, J. A. & Leidy, H. J. Breakfast consumption augments appetite, eating behavior, and exploratory markers of sleep quality compared with skipping breakfast in healthy young adults. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2, nzy074. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzy074 (2018).

Min, C. et al. Skipping breakfast is associated with diet quality and metabolic syndrome risk factors of adults. Nutr. Res. Pract. 5, 455–463. https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2011.5.5.455 (2011).

Deshmukh-Taskar, P. R., Radcliffe, J. D., Liu, Y. & Nicklas, T. A. Do breakfast skipping and breakfast type affect energy intake, nutrient intake, nutrient adequacy, and diet quality in young adults? NHANES 1999–2002. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 29, 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2010.10719858 (2010).

Solmi, F. et al. Longitudinal association between binge eating and metabolic syndrome in adults: Findings from the ELSA-Brasil cohort. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 144, 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13356 (2021).

Farshchi, H. R., Taylor, M. A. & Macdonald, I. A. Regular meal frequency creates more appropriate insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles compared with irregular meal frequency in healthy lean women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 58, 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601935 (2004).

Witbracht, M., Keim, N. L., Forester, S., Widaman, A. & Laugero, K. Female breakfast skippers display a disrupted cortisol rhythm and elevated blood pressure. Physiol. Behav. 140, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.12.044 (2015).

Inoue, K. et al. Urinary stress hormones, hypertension, and cardiovascular events: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension 78, 1640–1647. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17618 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.K., H.J.K., S.-M.J. and H.-K.J. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by S.-M.J. The first draft of the manuscript was written by H.M.K. and H.J.K. S.-M.J., D.H.L., H.-K.J. commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.M., Kang, H.J., Lee, D.H. et al. Association between breakfast frequency and metabolic syndrome among young adults in South Korea. Sci Rep 13, 16826 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43957-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43957-3

This article is cited by

-

Does breakfast skipping alter the serum lipids of university students?

BMC Nutrition (2025)