Abstract

The present study was aimed at showing the importance of HPV DNA status and the clinical history of the patients required by the cytologist for accurate reporting. A total of 1250 symptomatic women who attended the gynaecology outpatient department of the Mahavir Cancer Sansthan and Nalanda Medical College, Patna, for pap smear examinations were screened and recruited for the study. Due to highly clinical symptoms out of the negative with inflammatory smears reported, one hundred and ten patients were randomly advised for biopsy and HPV 16/18 DNA analysis by a gynaecologist to correlate negative smears included in the study. Pap smear reports revealed that 1178 (94.24%) were negative for intraepithelial lesions (NILM) with inflammatory smears, 23 (1.84%) smears showed low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), 12 (0.96%) smears showed high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, and 37 (2.96%) smears showed an atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASC-US). A biopsy of 110 out of 1178 (NILM) patients revealed that 15 (13.63%) women had cervical cancer, 29 women had CIN I, 17 women had CIN II + CIN III, 35 women had benign cervical changes, and 14 women had haemorrhages. On the other hand, HPV 16/18 DNA was detected as positive in 87 out of 110. The high positivity of HPV in biopsied cases where frank cervical cancer and at-risk cancer were also observed in the negative smear-screened patients reveals that the HPV status and clinical history of the patients will be quite helpful to the cytologist for accurate reporting, and suggests that a negative HPV DNA result may be a stronger predictor of cervical cancer risk than a negative Pap test.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pap cytology has been the cornerstone for screening cervical cancer since the past. This procedure is used to examine the changes in cervical cells which cause cervical cancer. Since Pap smear is simple and cost-effective test hence is widely used for early detection program, despite of that the cervical cancer burden is still high globally. As per GLOBOCAN 2020 statistics, globally 604,127 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer and 341,831 women died; in India alone, 1,23,907 new cases were diagnosed and 77,348 died1. In many studies, the sensitivity of the Pap smear was found to be < 70%2,3,4, and consequently, in some of the cases, cervical cancer was diagnosed as cervical dysplasia when screened by Pap smear method. Error in the sample collection is a big issue because it is difficult to reach an adequate level of coverage5,6,7, another issue is the optimal collection of samples & the lack of well-trained persons for drawing the sample8. Interpretation of cytology is very subjective despite the presence of abnormal cells9,10, therefore frequent repeated screening is recommended.

Cervical cytology screening in recent years has become challenging, as cytology screening programmes have shown a low success rate in reducing cervical cancer burden in developing countries11. In the United Kingdom, studies have also shown that Pap smears are imperfect and that 50% of invasive cancers are detected in women who have been adequately screened12. In Toronto, Ontario, a cancer screening performance report showed that a proportion of women presented with locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC) within three years after a negative Pap. In Thailand, the Pap test could not detect even a single case in 21 women with CIN 2 + lesions13. Therefore, they reviewed the cervical screening strategy and added HPV testing for screening for cervical neoplasia. It is well established from epidemiological, clinical, and experimental investigations that cervical cancer is caused by genital tract infection with the oncogenic form of human papillomavirus. Cervical cancer is thought to be caused by oncogene types 16 and 1814,15,16,17,18,19. Oncogenic high-risk types 16, and 18 are commonly detected in cervical malignancies worldwide20,21, and more than 80% of Indian women with cervical cancer contain HR-HPV strains 16 and 18. In India, HPV type 16 is more prevalent than HPV type 18, accounting for 90% of cervical cancer incidences of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. HPV 18 is extremely rare, with a frequency of just 3–5%22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

According to studies, the specificity of Pap smear is 86–100%31, whereas sensitivity ranges from 30–87%31,32, which explains why the chances of missing precancerous lesions in screening programmes are high. "European quality assurance guidelines recommended rescreening of those slides that were screened as negative cytology"33. In India, the presence of cervical cancer in an advanced center is found at stages III and IV despite routine Pap smear examinations. This shows a lot of constraints in Pap smear reporting, which might be errors in sampling, optimal collection, unable to reach the transformation zone, a lack of patient history at the time of reporting, and moreover, interpretation is very subjective.

The aim of this study was to highlight the importance of HPV DNA status and the clinical history of patients as supplements for cytologists while examining Pap smear slides. The current study also aimed to determine whether a negative HPV DNA result was a better predictor of cervical cancer risk than a negative Pap test.

Methodology

Study subjects

A total of 1250 women were screened during the period of August 2022 to July 2023 who attended the gynaecology outpatient department of the Mahavir Cancer Sansthan and Research Centre and Nalanda Medical College Patna, (Bihar) India, between the age group of 22–75 years were included in the study. Presenting with various symptoms like chronic vaginal discharge with a foul smell, pelvic pain, heavy menstrual bleeding, post-menopausal bleeding and post coital bleeding.

Out of negative with inflammatory smears (NILM) reported, one hundred and ten were randomly advised due to highly clinical symptoms for colposcopy guided biopsy and HPV 16 and18 DNA analysis by a gynaecologist. The histopathological examination was done as the reference standard to correlate negative inflammatory Pap smear cases and HPV types 16 and18 results.

Specimen collection

Cervical scrapes were collected by scraping the cervix area using an Ayre’s spatula for Pap smear examinations and HPV testing. After smearing the slides for a Pap test, the remaining scraped cervical cells, along with the spatula, were transferred to sterile vials containing 10 ml of cold PBS and kept at − 20 °C for further DNA extraction as per the requirements of the study.

Pap test

A cervical smear was made with the help of an endocervical brush, an Ayre’s spatula, and a cotton swab by the gynaecologist. Smears were fixed immediately in 95% isopropyl alcohol and stained with Papanicolaou stain for observation. Reporting of Pap smears was done based on the revised Bethesda system of 2014 by the pathology department of the Mahavir Cancer Sansthan & Research Centre.

DNA extraction from cervical scrapes

DNA extraction was made using MyLab Discovery Solutions kit which was based on silica membrane technology and the whole process involved the steps of sample lysis, DNA binding to the silica columns, and washing elution.

DNA Isolation: 200 µl of cervical samples were taken from the sample collection tube and added to 20 µl of lysis enhancer buffer. After that, 20 µl of RNA out solution was added. After mixing and vortexing, the sample was incubated for 2 min at room temperature. A further 20 µl of lysis enhancer buffer was added and mixed by vertexing to get a homogeneous solution. Incubated the solution at 55 °C on a heat block for 10 min to promote protein digestion. Then 200 µl 96–100% ethanol was added and vortexed for 5 s to yield a homogeneous solution then proceeded for binding of DNA.

Binding and washing of DNA

Added 250 µL binding buffer, cap the tube, and mixed by vertexing it for 10 s. Added the content of the tube into the Spin membrane column and centrifuged it for one minute at 10,000Xg RPM at room temperature. Removed the collection tube containing the flow through and discarded it. After that placed the spin membrane column into a clean collection tube and added 500 µl of wash Buffer to spin column at the center. Centrifuged the spin column at 13,000 × g for 3 min at room temperature. Discarded the flow through from collection tube, repeated the washing step one more time, using a different collection tube for a second wash. In order to dry the column with attached DNA, centrifuged the spin column with the collection tube at 13000Xg for 1 min at room temperature and discarded the collection tube. Finally placed the spin column in a sterile 1.5 mL micro centrifuged tube and proceeded to Elution buffer of the DNA.

Elution Buffer of DNA: Added 50 µL of Elution Buffer to the Spin membrane column, incubated at room temperature for 01 min and centrifuged the spin column at 15000Xg for 1 min. The micro-centrifuge tube contains purified genome DNA and discarded the spin column from the micro-centrifuge tube. The eluted DNA is stored at − 20 °C until use for further processing.

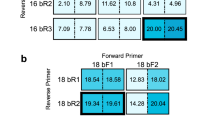

Amplification of specific E6/E7 region of HPV types 16 and 18

The HPV test was done using the MyLab Discovery Solutions kit. The test was based on Real Time PCR-based technology, for the amplification of specific conserved target sequence of E6/E7 region of HPV 16 as well as 18 and detection by target specific probe. Endogenous internal control is also detected as a housekeeping gene to check for extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition. The assay principle is based on Taqman technology which allows for higher specificity and sensitivity.

Histopathological examination

Randomly advised 110 women with negative inflammatory Pap smears were subjected to a punch biopsy with the help of colposcopy examination after the application of 5% acetic acid. A digital colposcope was used, and tests were performed using both Schiller and vinegar. The colpogram was assessed on a Reid score. The gynaecologist had taken the punch biopsy wherever it was necessary and sent it to the pathology department of the Mahavir Cancer Sansthan for histopathological examination.

Statistical analysis

The association of HPV 16/18 DNA with histopathological abnormalities was compared in Pap smear negative patients by statistical analysis using the Chi-square test with prism software.

Ethical approval

The informed consent was obtained from all recruited participants and the study was explained orally to all healthy women. The study was reviewed and approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee with IEC No. MCS/Admin/2018-19/1223dated 23/08/2018. The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines and principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Results

In the present study, 1250 Pap test results of symptomatic women were studied with reference to the smear findings and age group of the patients. Pap smear reports revealed that 1178 (94.24%) were Negative for Intraepithelial Lesion (NILM) with inflammatory smear, 23(1.84%) smears showed low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), 12 (0.96%) smears showed high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion(HSIL), and 37 (2.96%) smears showed Atypical Squamous Cell of Undetermined Significance (ASC-US). (Table 1). However, It was found that negative for Intraepithelial Lesion or malignancy (NILM) was observed in all age groups of patients, and inflammation was reported in most of them. Atypical Squamous Cell of Undetermined Significance (ASC-US) was reported maximum in the age group of 41–50, followed by age group of 51–60 years. Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) & high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) were also reported maximum in the age group of 41–50 (Table 2).

A biopsy of 110 randomly advised patients revealed that, 15 (13.63%) women had cervical cancer, of which 06 had a Keratinizing Squamous cell carcinoma, 05 had a Keratinizing Squamous cell carcinoma and 04 had an Adenocarcinoma. (Table 3). 29 women had CIN I, 17 women had CIN II + CIN III, 35 women had benign cervical changes, and 14 women had haemorrhages. On the other hand, HPV 16/18 DNA was detected as positive in 87 out of 110. Further, the high prevalence of HPV positive women was correlated with histopathological reports to correlate the HPV types 16/18 results in negative inflammatory Pap smear cases. HPV 16/18 was detected (15/15)100% in cervical cancer cases, (27/35) 77.14% in benign cases, (20/29) 68.96% in CIN I, (14/17) 82.35% in CIN II + CIN III cases, and (11/14) 78.57% in haemorrhagic cases. The association of HPV 16/18 DNA with histopathological abnormalities was compared in Pap smear negative patients and the association was found to be significant. X2—3.63, df = 1, p < 0.05. (Table 4).

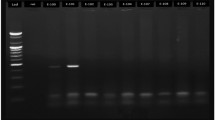

After the histopathological examination, a case of Pap smear slide was rescreened, which was reported to be negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) with inflammation (Fig. 1), and a cluster of abnormal cells was observed in one focus only that was missed in screening (Fig. 2), and found to be adeno carcinoma (Fig. 3). In addition, HPV 16/18 DNA status was detected as positive in them.

The association of HPV 16/18 DNA with histopathological abnormalities were compared in Pap smear negative patients and the association was found to be significant. X2—3.63, df = 1, p < 0.05.

Discussion

The intention of the present study was to demonstrate that negative Pap test results are caused by not only inaccurate sample collection and preparation but also incorrect interpretation, which may be the vital reasons for negative Pap test results for cervical lesions in symptomatic women. Pap test smears remain controversial in pathology as it is difficult to interpret different cytologic patterns like abnormal glandular cell groups, hyperchromatic crowded cell groups, and abnormally immature metaplastic squamous cells. In the light of negative Pap test results Austin et al.34 explained in their study with examples of a case. A case of postmenopausal woman who visited a primary care physician with a complaint of abnormal bleeding. The patient already had a history of uterine cancer but the patient still had a cervix & uterus hence Pap test was sent to the laboratory with mentioning the history of abnormal bleeding in Pap requisition but did not mention the history of cancer. The Pap test was elucidated as negative because abnormal cell clusters were undetected. The patient further consulted to general surgeon as the bleeding continued. The surgeon examined her, but a biopsy was not performed. At last, after 20 months patient was examined by a gynaecologist who made a biopsy and diagnosed her with recurrent cervical cancer. The negative Pap test result represented to fails the chance of an early diagnosis.

Frable et al.35 observed in their study that negative Pap test results claim errors in clinical management of patients having abnormal signs & symptoms. It delays the further diagnostic test like colposcopy or biopsy, consequently with delayed tests, dysplasia changes into neoplasia. The study of Zhao et al.36 also observed negative Pap test results findings in women suffering from endometrial neoplasia: thus, they mentioned in their study that Pap test has low sensitivity to detect endometrial neoplastic changes.

It was observed in our present study that more than 70% of patients came with the most common complaint of chronic per vaginal discharge with foul smelling and pain in the pelvic area. The second most common problem was heavy menstrual bleeding and post-menopausal bleeding, and the least common was post coital bleeding. It was also observed that all patients were referred to an advanced centre to rule out cervical malignancy as their primary screening was already done at the local level, despite the fact that 94.24% of smears were reported as Negative for Intraepithelial Lesions (NILM) with inflammation in an advanced centre. The high incidence of vaginal discharge cases in our study population were reported as inflammatory smears but since lesions were not observed by a cytologist, a biopsy was advised by a gynaecologist to correlate negative smears. A biopsy revealed that, 15 (13.63%) women had cervical cancer, of which 06 had a Keratinizing Squamous cell carcinoma, 05 had a Keratinizing Squamous cell carcinoma and 04 had an Adenocarcinoma. 29 women had CIN I, 17 women had CIN II + CIN III, 35 women had benign cervical changes, and 14 women had haemorrhages. After the histopathological examination, a case of Pap smear slide was rescreened, and a cluster of abnormal cells was observed in one focus only that was missed in screening and found to be adenocarcinoma. Thus, in our study, we have also observed that the negative Pap test result represents a failure of the chance of early diagnosis, which is in fair agreement with the studies of Austin et al. and Frable et al. Our present study supports the work of the mentioned authors and suggests that a complete patient history is important to evaluate shuttle change in smears.

On the other hand, there is a strong relation between chronic inflammation and cancer in which autocrine and paracrine signals are arbitrated by oncogenic activity, which gives rise to changes in somatic cells with the impact of epigenetic factors or the microbial genome. Among the infectious agents that are responsible for cancer of the human papillomavirus is well established. Fernandes et al.37 observed in their study that human papillomavirus is responsible as an invading agent against inflammatory response which activates stimulus for the release of cytokines and chemokines. These mediators act together to employing the effector cells on the wound for healing and removes the stimulus to disable inflammation. Even so if, stimulus continues inflammation changes into chronic and strongly linked with the development of cervical cancer. Deivandran et al.38 and Hemmat et al.39 both have also observed in their study that human papillomavirus (HPV) is responsible for acceleration of inflammation and changes into chronic inflammation involved in the process of cervical cancer.

In our present study, HPV 16/18 DNA was detected as positive in 87 out of 110 who reported inflammatory smaers. Further, the high prevalence of HPV positive women was correlated with histopathological reports to correlate the HPV types 16/18 results in negative inflammatory Pap smear cases. HPV 16/18 was detected (15/15)100% in cervical cancer cases, (27/35) 77.14% in benign cases, (20/29) 68.96% in CIN I, (14/17) 82.35% in CIN II + CIN III cases, and (11/14) 78.57% in haemorrhagic cases. The association of HPV 16/18 DNA with histopathological abnormalities was compared in Pap smear negative patients and association was found to be significant. X2—3.63, df = 1, p < 0.05. Thus, our study supports the work of Deviandran et al. and Hemmat et al. that inflammation should not be ignored, especially when it persists, as it is the key process involved in the progression of cervical cancer.

The study of Koliopoulos et al.40 also supports our present study that HPV tests were shown to be statistically significantly more sensitive for CIN2 + detection than both conventional cytology and LBC, with relative sensitivities of 1.52 and 1.18, respectively. Specificity was significantly lower for HPV testing (with relative specificities of 0.94 for the Pap test and 0.96 for LBC).

Conclusion

The investigation done on the Pap test results of symptomatic women revealed that the interpretation of the smear by the cytopathologist is quite crucial. Microbial and epigenetic factors are responsible for making changes in cervical cells, and HPV is proven to be a causative agent for the development of cervical cancer. Therefore, the HPV status of the patients will be very helpful for the cytopathologist to interpret the changes in cervical cells, and it could be suggested that a negative HPV DNA result is a better predictor of cervical cancer risk than a negative Pap test.

Along with this, at the time of the smear examination, the cytopathologist must know the clinical history of the patient in order to evaluate changes in the cell. In our study, the data reveals that more than 90% of Pap test results were reported as inflammatory smears. If the cytopathologists knew the HPV status and clinical history of the patients, then the interpretation of the smear would have been conclusive. Thus, the study concludes with the finding that a Pap smear study must be done by the cytopathologists in light of the clinical history of the patients and HPV status to detect cervical cancer and its precursors, CIN 2 and CIN 3 lesions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H., Ferlay, J. & Siegel, R. L. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71(03), 209–249 (2021).

Bhattacharyya, A. K., Nath, J. D. & Deka, H. Comparative study between pap smear and visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) in screening of CIN and early cervical cancer. J. Midlife. Health 6, 53–58 (2015).

Bobdey, S. et al. Cancer screening: should cancer screening be essential component of primary health care in developing countries?. Int. J. Prev. Med. 6, 56–65 (2015).

Karimi-Zarchi, M. et al. Comparison of Pap smear and colposcopy in screening for cervical cancer in patients with secondary immunodeficiency. Electron. Phys. 7, 1542–1548 (2015).

Nayar, R. & Wilbur, D. C. The Pap test and bethesda 2014. Acta Cytol. 59, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381842 (2015).

Ruba, S., Schoolland, M., Allpress, S. & Sterrett, G. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: Screening and diagnostic errors in Papanicolaou smears. Cancer 102, 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20600 (2004).

Schoolland, M., Allpress, S. & Sterrett, G. F. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Cancer 96, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10313 (2002).

Castanon, A., Landy, R. & Sasieni, P. D. Is cervical screening preventing adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix?. Int. J. Cancer. 139, 1040–1045. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30152 (2016).

Bulk, S. et al. High-risk human papillomavirus is present in cytologically false-negative smears: An analysis of “normal” smears preceding CIN2/3. J. Clin. Pathol. 61, 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2006.045948 (2008).

Komerska, K. et al. Why are Polish women diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer after negative cytology in the organized screening programme—A pilot reevaluation of negative Pap smears preceding diagnoses of interval cancers. Pol. J. Pathol. 72, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.5114/pjp.2021.112832 (2021).

Sankaranarayanan, R. Screening for cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. Global Health 80(5), 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2014.09.014 (2014).

Brinkmann, D., Gladman, M. A., Norman, S. & Lawton, F. G. Why do women still develop cancer of the cervix despite the existence of a national screening programme?. Eur. J. Obstetrics Gynecol. Reproductive Biol. 119(1), 123–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.07.021 (2005).

Khuhaprema, T. et al. Organization and evolution of organized cervical cytology screening in Thailand. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Feder. Gynaecol. Obstetrics 118(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.031 (2012).

Reeves, W. C., Brinton, L. A., Garcia, M. & Brenes, M. M. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer in Latin America. N. Engl. J. Med. 320(22), 1437–1441 (1989).

Bosch, F. X. et al. Risk factors for cervical cancer in Columbia and Spain. Int. J. Cancer 52, 750–758 (1992).

Eluf-Neto, J. et al. Human papillomavirus and invasive cervical cancer in Brazil. Br. J. Cancer 69, 114–119 (1994).

Kouri, M. T. et al. HPV prevalence among Mexican women with neoplastic and normal cervices. Gynaecol. Oncol. 70, 115–120 (1998).

Chinchareon, S. et al. Risk factors for cervical cancer in Thailand: A case control study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90(1), 50–57 (1998).

Bosch, F. X., Munoz, N. & Sanjose, S. D. Human papillomavirus and the other risk factors for cervical cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 51, 268–275 (1997).

Walboomers, J. M., Jacobs, M. V. & Manos, M. M. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 189, 12–19 (1999).

Bosch, F. X. & de Sanjose, S. Chapter 1: human papillomavirus and cervical cancer-burden and assessment of causality. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 31, 3–13 (2003).

Das, B. C., Gopalkrishna, V. & Das, D. K. Human papillomavirus DNA sequences in adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix in Indian women. Cancer 72(1), 147–153 (1993).

Iwasawa, A., Nieminen, P., Lehtinen, M. & Paavonen, J. Human papillomavirus DNA in uterine cervix squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma detected by polymerase chain reaction. Cancer 77(11), 2275–2279 (1996).

Das, B. C., Sharma, J. K., Gopalakrishna, V. & Luthra, U. K. Analysis by polymerase chain reaction of the physical state of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in cervical preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions. J. Gen. Virol. 73, 2327–2336 (1992).

Kailash, U., Soundararajan, C. C. & Lakshmy, R. Telomerase activity as an adjunct to high-risk human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 and cytology screening in cervical cancer. Br. J. Cancer 95(9), 1250–1257 (2006).

Pande, S., Jain, N. & Prusty, B. K. Human papillomavirus type 16 variant analysis of E6, E7, and L1 genes and long control region in biopsy samples from cervical cancer patients in north India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46(3), 1060–1066 (2008).

Bhatla, N., Dar, L. & Rajkumar, P. A. Human papillomavirus-type distribution in women with and without cervical neoplasia in north India. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 27(3), 426–430 (2008).

Bhatla, N., Dar, L. & Patro, A. R. Human papillomavirus type distribution in cervical cancer in Delhi. India. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 25(4), 398–402 (2006).

Franceschi, S., Rajkumar, T. & Vaccarella, S. Human papillomavirus and risk factors for cervical cancer in Chennai, India: A case–control study. Int. J. Cancer. 107(1), 127–133 (2003).

Sowjanya, A. P., Jain, M. & Poli, U. R. Prevalence and distribution of high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) types in invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and in normal women in Andhra Pradesh. India. BMC Infect. Dis. 5, 116 (2005).

Nanda, K. et al. Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 132, 810–819. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00009 (2000).

Mustafa, R. A. et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the accuracy of HPV tests, visual inspection with acetic acid, cytology, and colposcopy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 132, 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.07.024 (2016).

Anttila A., Arbyn M., De Vuyst H., Dillner J., Dillner L., Franceschi S., Patnik J., Ronco G., Segnan N. & Suinio E. European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. 2nd ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: (2008). [Google Scholar]

Austin, R. M. & Zhao, C. Observations from Pap litigation consultations. Pathol. Case Rev. 16(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCR.0b013e31820fff8a (2011).

Frable, W. J. Error reduction and risk management in cytopathology. Semin. Diagnostic Pathol. 24(2), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2007.03.006 (2007).

Zhao, C., Florea, A., Onisko, A. & Austin, R. M. Histologic follow-up results in 662 patients with Pap test findings of atypical glandular cells: Results from a large academic womens hospital laboratory employing sensitive screening methods. Gynecol. Oncol. 114(3), 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.019 (2009).

Fernandes, J. V. et al. Link between chronic inflammation and human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis (Review). Oncol. Lett. 9(3), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2015.2884 (2015).

Deivendran, S., Marzook, K. H. & Pillai, M. R. The role of inflammation in cervical cancer. InInflammation and cancer 377–399 (Springer, Basel, 2014).

Hemmat, N. & Bannazadeh, B. H. Association of human papillomavirus infection and inflammation in cervical cancer. Pathogens Dis. 77(5), ftz048 (2019).

Koliopoulos, G. et al. Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD008587. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008587.pub2 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Mahavir Cancer Sansthan & Research Centre, Patna for his valuable inputs and support.

Funding

The financial support/funding for the study was provided by Mahavir Cancer Sansthan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A Conceptualized the entire work, M.A had the major contributions in writing the manuscript but support was also provided by M.I.. Sh.K.,A.K., A.G., literature search was done by S.K.,and Sh.S., data were collected by A.K., S.K., Sh.S, experimental work and data analysis were done by M.A, S.K, and A.K., data interpretation was carried out by M.A, S.K., A.G., A.K., and M.S., R.S and A.K done pathological work beimg a pathologist final figures were designed by M.A.. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, M., Sinha, R., kumar, A. et al. HPV DNA status and clinical history of patients are supplements for accurate reporting of the cytological Pap smear. Sci Rep 14, 17486 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68344-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68344-4