Abstract

Earthquakes that cause extensive damage occur frequently in Japan, the most recent being the Noto Peninsula earthquake on January 1, 2024. To facilitate such a recovery, we introduce a community-based participatory research program implemented through cooperation between universities and local communities after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. In this project, the university and the town of Shichigahama, one of the affected areas, collaborated to hold annual workshops in the target area, which evolved into a climate monitoring survey. Even in Japan, where disaster prevention planning is widespread, various problems arise in the process of emergency response, recovery and reconstruction, and building back better when disasters occur. As is difficult for residents and local governments to solve these problems alone, it is helpful when experts participate in the response process. In this study, we interviewed town hall and university officials as representatives of local residents regarding this project and discussed their mutual concerns. The community-based participatory research framework developed in the Shichigahama project could be used in the recovery from the Noto Peninsula Earthquake as well as in future reconstruction and disaster management projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Japan is a country often subject to natural disasters. In the Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture, earthquakes (in the crust) have been on the increase since around 2018, and seismic activity has been active since December 2020, and became more active around May 2023. The area of earthquake occurrence has expanded with further increase in seismic activity. The largest earthquake to date was an M7.6 earthquake on January 1, 2024 (depth of 16 km, intensity 7 in Wajima City and Shiga Town, Hakui County)1. Support for victims in the affected areas is currently being provided by the government and medical personnel, among others. The reconstruction of the Noto Peninsula following the earthquake will be led by local governments2. The recovery process requires interventions that focus on the participation of the affected communities and the strengthening of local resources3.

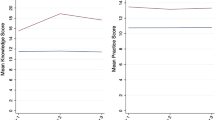

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has been identified as an important approach to promote recovery from and resilience after disasters4. Several regions have successfully identified and addressed disaster recovery issues through community-based approaches5. Globally, the importance of and need for community-based research is increasingly recognized in the context of disasters such as the Iraq War6, landslides7, floods8, hurricanes9,10,11, and bushfires12,13. In the Japanese context, awareness of the importance of CBPR has increased since the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake14,15 and has been reported in relation to the Kumamoto earthquake16 and floods17 (Fig. 1A). In general, recovery from natural disasters such as major earthquakes take about ten years18,19. The period from the time of the disaster to the year in which the CBPR was implemented is shown: Fig. 1b shows the survey for the non-Japan cases, and Fig. 1c shows the survey for the Japan cases. As can be seen in Figs. 1b,c, most studies were conducted within ten years of disasters and many were launched within a few years after the disaster. Conducting CBPR within a few years after a disaster is suitable for examining problems and the progress of reconstruction in the acute and mid-term post-disaster period, but a comprehensive evaluation of reconstruction is not possible because the affected area is still in the process of recovery.

(A): Examples of the use of community participatory surveys in disaster recovery. (B): Time elapsed between the occurrence of disasters around the world and the implementation of community participatory surveys. (C): Time elapsed between the occurrence of disasters in Japan and the implementation of community participatory surveys.

Here, we introduce the CBPR efforts conducted by the Tohoku University Core Research Cluster for Disaster Science in the town of Shichigahama, one of the areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, eight to nine years after the disaster. The Core Research Cluster of Disaster Science is a new discipline established at Tohoku University, a designated national university. The discipline was born in June 2017 in recognition of the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to hazards and recovery20. The research cluster is composed of eight institutions: the Graduate School of Arts and Letters; Graduate School of Natural Science; Graduate School of Environmental Science; Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer; International; Research Institute of Disaster Science; Center for Northeast Asian Studies; and the Hospital and School of Medicine21. The research cluster has two overall purposes: (1) to develop and systematize disaster science and (2) to contribute to support for recovery, reconstruction, and building back better in affected areas; disaster risk reduction and mitigation; and the development of human resources in international societies22.

The research cluster recognizes the importance of the CBPR approach in the field of hazards and recovery. As Tohoku University has long had a research base in the town of Shichigahama, which faces Sendai Bay, the approach has been applied to studying seaweed producers and their lifestyles in the town for a year and a half23. Additionally, Plaza et al. analyzed the reproductive performance of female specimens of black sea bream collected from Shichigahama from October 2000 to March 200124. Following the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Disaster Psychiatry Department at Tohoku University and the International Research Institute of Disaster Science collaborated with the Shichigahama Town Hall over ten years to observe and improve community health25,26,27.

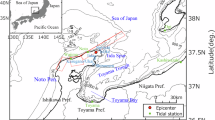

After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the Shichigahama Town–Tohoku University partnership was developed in the context of this larger movement utilizing CBPR approaches to intervention research in recovery and disaster prevention. Figure 2A shows earthquakes and affected prefectures in Japan as a whole, and Fig. 2B shows the town of Shichigahama in Miyagi Prefecture and the areas inundated by the Great East Japan Earthquake tsunami. The International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University, has been involved in mental health activities in the town of Shichigahama since the Great East Japan Earthquake28,29. Annual surveys were conducted over a ten-year period from November 2011, eight months after the disaster, to 2020 for residents of Shichigahama Town (2,282 adults; 106 minors) whose houses had been severely damaged or partially or entirely destroyed. The results of the posttraumatic stress reaction survey30,31,32,33 and psychological distress as indicators of mental disorder are shown in Fig. 2 (Panels C and D). The percentage of respondents with a posttraumatic stress reaction above a certain level (score of 25 or higher) on the Impact of Event Scale-Revised34 and the percentage of those with a relatively mild posttraumatic stress reaction (score of less than 25) are shown in Fig. 2C. The proportion of those showing a certain level of posttraumatic stress reaction peaked at 32% in FY2011 and 33% in FY2012, with a gradual improvement in FY2013 and a decrease to 6% in FY2020. Psychological distress was assessed using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale35. Figure 2D shows the percentages and trends for each of the four severity levels. The proportion of respondents who scored less than 5 points and were in relatively good mental health was 50% in FY 2011 and increased from FY 2012 to 2014; after leveling off in FY 2015–2017, it increased again from FY 2018 onward.

(A): Earthquakes in Japan and affected prefectures from 1995 to 2024. The base map was created with Frame illust, 2014 software, a free opensource software https://frame-illust.com/?cat=256, color-coding Japanese regions. (B): Damage to Shichigahama Town by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Left inset: Japan and the ___location of the epicenter of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Right inset: Areas of Shichigahama Town flooded by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Map background image source and license: Maps were created using ArcGIS Pro (ver. 3.3.1, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview) and the prefecture level boundaries of Japan in ArcGIS Hub. ArcGIS are the intellectual property of Esri and are used herein under license. Copyright (c) 2024 Esri Inc. All rights reserved. For more information about Esri software, please visit www.esri.com. Fukkou Shien Chosa Archive: Shichigahama town – Inundated Area, City Bureau of the Land, Infrastructure and Transportation Ministry of Japan and the Center for Spatial Information Science of the University of Tokyo (2012) (in Japanese) http://fukkou.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/, Accessed Aug 2023. (C,D): The results of the post-traumatic stress reaction survey and psychological distress as indicators of mental disorder (modified from Tomita et al. 2020 and Hamaie et al. 2022).

This study aimed to assess whether CBPR engaging affected communities and professionals improves their resilience to disasters long after the disaster has passed. This paper first introduces the Shichigahama Town project, a collaborative study with Tohoku University focusing on the town of Shichigahama after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Next, we present the results of the analysis of CBPR conducted after the disaster, a discussion of CBPR, and the conclusions of this study.

Method

Relationship between Shichigahama and academia

Overview of Shichigahama town

The town of Shichigahama faces the sea on three sides and is located on a peninsula. The population was 18,358 as of June 1, 2023. The fishing industry has flourished there since ancient times, with nori (seaweed) cultivation being a representative basic industry of the region. Abalone, sea urchins, and fish are abundantly available in the region.

As a result of the tsunami triggered by the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, 36.4% of the urban area was inundated and suffered enormous damage, and there were 99 fatalities (Fig. 2B). The maximum height of the tsunami inundation was 12.1 m. After this incident, the Shichigahama Town Earthquake Reconstruction Basic Policy was formulated on April 25, 2011, aiming to “create a comfortable and livable town in which people can live in harmony with nature, taking into account safety and security.” In addition, the Disaster Recovery Early Basic Plan (2011–2015) was formulated on November 8, 2011. Based on this, the policy and priority actions for recovery were formulated. On April 6, 2012, a policy on land use rules for the affected areas was formulated, dividing the town and use into four categories and presenting their reconstruction measures.

Shichigahama town workshop

A practical workshop was developed for Shichigahama Town Hall and the Tohoku University Disaster Science Designated National College Core Research Cluster. The first workshop was held on September 12–13, 2019, with twenty-three participants from Tohoku University and six from the town hall. This was followed by the second (September 24, 2020) and third (September 17, 2021) workshops, which were held remotely to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

The first workshop introduced Shichigahama Town Hall staff and Tohoku University researchers to the research related to Shichigahama Town that Tohoku University had conducted up to that point. On the morning of the second day, the staff of Shichigahama Town Hall presented the disaster prevention facilities. The Tohoku University researchers traversed Shichigahama Town to improve their understanding of the facilities by entering the shelters and checking the breakwater height. In the workshop that followed, the researchers discussed potential methods for improving Shichigahama Town's resilience to disasters. The content of the workshop was shared by the researchers and Shichigahama Town Hall (Fig. 3).

(A): Three layers of the Shichigahama Town Project. Overview of the Shichigahama Town project over a three-year period from 2019 to 2021. (B): Summary of findings related to the interview. Summary of the Shichigahama Town project findings identified using the grounded theory method coding paradigm. Green boxes indicate the period; light blue boxes indicate what was done during the period.

Procedure

To answer our research questions, we used a qualitative approach, specifically the grounded theory method (GTM) for data collection and analysis36,37. The GTM is an inductive approach commonly used with participant observation and interview data38. Interviews were the primary source of data: from January 12–March 28, 2022, the authors interviewed six officials from Shichigahama Town and the designated national college, the Core Research Cluster for Disaster Science, and staff from Tohoku University.Table 1 shows the roles of the interviewees, indicating their function within the project in the case of town officials and their specialty in the case of university faculty. Supplementary file 1 shows what they were doing at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake.

The interviews focused on the respondents’ satisfaction with the workshop in Shichigahama Town. We asked about the community’s general perception of what they expected from disaster preparedness and response, what information they needed, why they needed information and how they wished to receive it, and their thoughts about a future collaboration between the community and the university. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Qualitative analysis (including coding and note-taking) followed the axiality coding paradigm according to the GTM39.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods including experiments, analyses, and interviews were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University (approval number: 2021–039). All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University, and all human participants gave informed consent.

Results

Theme 1: first workshop as a collaboration between the community and academia

Regarding the first Shichigahama workshop, Tohoku University faculty members said, “From the very beginning, I thought Shichigahama was a bit of a mystery, and as I mentioned at the time, we were talking about Tohoku and Japan at the most. Even in Miyagi Prefecture, we were only talking about the Miyagi earthquake, and I did not know what we could talk about or what we could contribute at the municipal level” (Professor B, Tohoku University); “Shichigahama had a major tsunami disaster, but very few weather-related disasters, so it was difficult to find a connection in terms of what we could do” (Professor C, Tohoku University). A Shichigahama Town official said, “No, when we were first approached, one of the things we were wondering about was what we could do. It would be nice if we were in a situation where we could get some advice” (Shichigahama Town Official B).

Regarding the first Shichigahama town workshop, one participant said, “We met with everyone and had the mayor and other stakeholders with us, and we asked them, ‘What are you doing?’ We brainstormed about what we were doing and how we were going to work together, and we compiled a list of keywords” (Professor A, Tohoku University).

At the same workshop, Staff Member A said, “I accompanied the teachers on their site visit. I was glad to guide them and tell them that although the area was damaged at the time, it has recovered to what it is today.” Staff Member F said, “I was happy to be able to show them around the site and tell them that although the area was damaged at the time, it has now been restored. That was very reassuring. We were very grateful to be able to talk directly to people who specialize in this kind of research.” Staff Member B said, “At the time, we felt that we could not enter the site.”

During the first Shichigahama town workshop, Tohoku University teachers said: “We were able to hear many things directly from the staff at that time, weren’t we? It’s not often you get a chance to hear such real voices” (Professor D, Tohoku University) and “The local government officials gave presentations that gave me a sense of fulfillment that they had already done what they could do, and I felt both envious and distressed” (Professor B, Tohoku University).

Theme 2: one example introduced from the “weather observation equipment” workshop

After the first workshop, Professor B said, “Apparently, there is no Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System (AMeDAS) there. If there is an AMeDAS, we could check it. By contrast, since there is no AMeDAS, I thought it would be worthwhile to see,” and the weather observation equipment was installed in Shichigahama Town. According to data reported by the Fire and Disaster Management Agency of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the number of people transported to emergency hospitals for heat stroke in Japan during the period from June to September has increased significantly since 2010, with 92,710 in 2018, a particularly extremely hot summer, followed by 66,869 in 2019 and 64,869 in 2020. Although the town of Shichigahama has made progress in reconstruction after the Great East Japan Earthquake, this workshop found that the town had not been able to observe the recent weather disasters.

At the second and third Shichigahama Town symposiums, Professor C had a dialogue with town officials: “We made contacts to talk with local people. Then, on the third occasion, they told us many stories from the other side. When I explained that this is how the data shows the weather in Shichigahama Town, it did not appear unusual to them; but since it is my town’s weather observation, they were interested in it. Then they would mention all sorts of problems.” “At the third Shichigahama Town workshop, we were told that although there are no weather disasters, there are two problems: one is that high levees have been built, and the water rises inside, causing problems such as inland flooding. As for global warming, it seems that the types of fish that can be caught are changing rapidly.”

Shichigahama Town Staff Member A said of the weather observation equipment, “We had it installed on the rooftop. I was personally informed of this at the time, and the current department is the one that orders contractors to remove typhoon rains and snow, like today, and to spread snow-melting agents. So, we are using them for such things.”

Regarding the weather observation, Professor C said, “It would be great if the town of Shichigahama said they would maintain the weather measurement equipment in Shichigahama as well. The one for the sea is going to be discontinued. I wanted them to provide information to tourists and other visitors, but they did not raise awareness to that extent. Of course, there is the budget problem as well.” Professor D said, “That person has been there all along taking measurements and local data. In a sense, he must have a close relationship with Shichigahama, but I don’t see what kind of communication or involvement he has with the residents and the local government office.”

Theme 3: evaluation of the Shichigahama town project

Professor A said, “First of all, to listen to the real needs of the people in the town hall, we need to talk to them a little more frequently, rather than just meeting them at events, and it is still difficult to make progress without someone who understands the situation.” He continued, “Even now, people are looking for ways to make Shichigahama a better community. Even back then, we had several goals, such as valuing health and history, and because Shobuta-beach is so attractive, I wish I could have contributed a little more here.”

Professor E said, “There was talk of gender, and there was talk of weather; both are important, but I’m not sure where the integral part of what we are doing with Shichigahama lies. I think it would be fine to say that we are taking action with regard to both areas. I was a little unclear about that when I participated last year.”

The Shichigahama Town staff said: “Although we understand what we are doing now internally, I really feel that we need to let the residents know more about what we are doing” (Staff Member A); “I was hoping that people would learn more about the self-help part I mentioned earlier while listening to those workshops. I think it is difficult to connect with the public if they are not able to participate in the workshops” (Staff Member B).

Future development from the perspective of Shichigahama town and Tohoku university staff

Shichigahama Town Official F said, “Surprisingly, even if the administrative part can be organized at the government office, it is hard to have this kind of analytical ability.” “What about the review? We can compare with other municipalities, but I wonder if there is a part of the verification of recovery that can be done objectively; not immediately, but after 10 or 20 years,” said Shichigahama Town official E.

“Of course, the residents of the city are involved in this project. Nevertheless, I wondered if it would be possible to hold workshops or trainings for elementary and junior high school students instead of disaster preparedness or disaster education or teaching children the concept of disaster preparedness,” said Shichigahama Town Official A. “I still think it would be best if they looked at Shichigahama and then got that kind of advice,” said Shichigahama Town Official D. “I hope some of the content will be useful for residents, and I also hope there will be some advice for the government and county disaster management associations that run the evacuation centers,” said Shichigahama Town Official C.

Tohoku University Staff Member C said, “It will be very important to do so after a disaster has occurred to get into the community. Shichigahama’s experience was good. It was very interesting because it was an approach that I did not know much about.”

Discussion

The population of the four cities and towns in Okunoto40, which were severely damaged by the 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake, is as follows: Wajima City: 23,192 (December 1, 2023); Suzu City: 12,610 (November 30, 2023); Noto Town: 15,187 (January 1, 2024); Anamizu Town: 7326 (December 1, 2023). All of these cities and towns are recognized as “wholly depopulated” under the “Act on Special Measures Concerning Support for Sustainable Development of Depopulated Areas.” A municipality is considered depopulated if it meets the requirements below a certain level in terms of population decline rate, ratio of older adults, and financial strength index. Shichigahama Town had an estimated population of 17,429 on December 1, 2023, and had a day–night population ratio of 65.0% in the 2010 census, the lowest of any municipality in Japan. Thus, the population of the Noto earthquake-stricken area and the town of Shichigahama are similar, and we believe that CBPR targeting the Shichigahama town for reconstruction after the Great East Japan Earthquake may be helpful for Noto.

Flicker41 stated about CBPR, “It can (and often does) benefit everyone involved in the research process. But the benefits do not come without significant investment, nor are they necessarily equitably distributed.” This study evaluates CBPR conducted in Shichigahama and uses the GTM to analyze the data from twelve semi-structured interviews with CBPR recipients and implementers. Professor C, who participated in this survey, felt the need to convey academic knowledge to the general public in an easy-to-understand manner through the Shichigahama Town project and published a book intended for that population after the project was completed. The Shichigahama Town staff felt that having the support of university staff could make the explanations they provided to the general public more persuasive. However, questions remain regarding the sustainability of these and other effects. By contrast, the benefits secured by the new partnership between the university and the community may be seen as more sustainable.

Professor C and his colleagues in CBPR for the Shichigahama Town project found evidence that weather observations were not conducted in Shichigahama Town. This included problems such as not knowing the actual weather in Shichigahama Town because of the use of the nearby AMeDAS. Academic researchers have an ethical obligation to equip the community with the tools needed to sustain an intervention or become successful change agents beyond the project period42. During this project in Shichigahama Town, two meteorological instruments were adapted under a grant from the designated national college, the Core Research Cluster of Disaster Science. Unfortunately, the grant has since expired, and only one instrument was retained in Shichigahama Town. After establishing a community and academic partnership with a common goal, obtaining grants to fund the academic and community teams is necessary42. Academics have been made aware of the fact that community partner organizations often have little additional funding or resources to contribute to unfunded pilot projects, and this may be one such example.

There are no reports of cases in which CBPR has been used for post-disaster recovery and disaster prevention in Japan. In Nepal, community-led reconstruction activities have been conducted at various monuments immediately after earthquakes, and they have played an important role in preserving and maintaining cultural heritage43,44. Previous studies in Japan have used the CBPR approach to identify community health needs45,46 or to understand community perceptions of a particular health problem47. However, there are no reports of cases in which CBPR has been used for post-disaster recovery and disaster prevention in Japan.

One of the challenges for younger faculty actively involved in the community during CBPR is the time the process requires. This is particularly relevant for careers in CBPR, where it can (reportedly) take years to build and secure trust between academic and community partners48. Only one (Faculty F) of the three young faculty members on our academic team from the first term remained for the second and third terms.

An evaluation of CBPR efforts should include a community assessment49:

(1) Have new community structures or problem-solving mechanisms been introduced?; (2) Have new leaders emerged?; and (3) Is there evidence of a greater sense of community ownership or citizen participation?50,51,52. Suggestions for the future (disaster education for elementary and middle school students; direct communication with citizens) were made in this project, but the CBPR assessment scores indicate that they have not yet been achieved. One reason the suggestions have not been fully implemented may be related to COVID-19. During the second and third phases of the pandemic, scientists could not visit the communities directly, but were involved remotely.

Limitations

Our study used interviews with both Shichigahama Town officials and university faculty to test the effectiveness of CBPR in the Shichigahama Town workshop project. Although interviews with local residents would ensure the generalizability of our results regarding the effectiveness of CBPR, the second and third Shichigahama Town workshops and our interviews were conducted at a time when human contact was restricted to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, we focused on interviews with Shichigahama town officials who accepted the CBPR because they were unable to have contact with the general population. The fact that the evaluator was a town employee rather than a local resident could introduce bias, but we mitigated this by ensuring there was sufficient interview time. (Supplementary table)

Conclusions

The application of CBPR principles is essential to translate knowledge into sustainable community-level action through empowerment and collaboration. Further long-term research using the CBPR approach is needed to provide additional evidence of returns, which will facilitate investment and broader implementation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available owing to privacy and ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

04 October 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74238-2

References

Kanazawa Local Meteorological Office. “Seismic Activity and Disaster Prevention Matters Portal Site for the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake”. https://www.data.jma.go.jp/kanazawa/shosai/notojishinportal.html. Accessed July 7, 2024.

Pearce, L. Disaster management and community planning, and public participation: How to achieve sustainable hazard mitigation. Nat. Hazards 28, 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022917721797 (2003).

Cueto, R. M., Fernández, M. Z., Moll, S. & Rivera, G. Community participation and strengthening in a reconstruction context after a natural disaster. J. Prev. Interv. Community 43, 291–303 (2015).

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A. & Becker, A. B. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 19, 173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 (1998).

Sadiqi, Z., Trigunarsyah, B. & Coffey, V. A framework for community participation in post-disaster housing reconstruction projects: A case of Afghanistan. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 35, 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.11.008 (2017).

Shabila, N. P., Al-Tawil, N. G., Al-Hadithi, T. S. & Sondorp, E. Post-conflict health reconstruction: where is the evidence?. Med. Confl. Surviv. 29, 69–74 (2013).

Kabunga, A., Okalo, P., Nalwoga, V. & Apili, B. Landslide disasters in eastern Uganda: post-traumatic stress disorder and its correlates among survivors in Bududa district. BMC Psychol. 10, 287. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-01001-5 (2022).

Hakkim, A. & Deb, A. Empowering local response and community-based disaster mitigation through legislative policies: Lessons from the Kerala floods of 2018–19. J. Emerg. Manag. 21, 347–353 (2023).

Bushong, L. C. & Welch, P. Critical healthcare for older adults post Hurricane Ian in Florida. U. S. J. Public Health Policy 44, 674–684. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-023-00444-3 (2023).

Stukova, M. et al. Mental health and associated risk factors of Puerto Rico Post-hurricane María. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 58, 1055–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02458-4 (2023).

Engelman, A., Guzzardo, M. T., Muñiz, M. A., Arenas, L. & Gomez, A. Assessing the emergency response role of community-based organizations (CBOs) serving people with disabilities and older adults in Puerto Rico post-Hurricane María and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042156 (2022).

Watts, R. et al. Incidence and factors impacting PTSD following the 2005 Eyre Peninsula bushfires in South Australia—a 7 year follow up study. Aust. J. Rural Health 31, 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12909 (2023).

Fitzpatrick, K. M. et al. Health systems responsiveness in addressing indigenous residents’ health and mental health needs following the 2016 Horse river wildfire in Northern Alberta, Canada: Perspectives from health service providers. Front. Public Health 9, 723613. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.723613 (2021).

Saito, Y. et al. Outpatient rehabilitation for an older couple in a repopulated village 10 years after the Fukushima nuclear disaster: an embedded case study. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.5387/fms.2023-01 (2023).

Tashiro, A. et al. Coastal exposure and residents’ mental health in the affected areas by the 2011 great East Japan earthquake and tsunami. Sci. Rep. 11, 16751 (2021).

Matsuoka, Y. et al. Does disaster-related relocation impact mental health via changes in group participation among older adults? causal mediation analysis of a pre-post disaster study of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. BMC Public Health 23, 1982. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16877-0 (2023).

Kitagawa, K. & Samaddar, S. Widening community participation in preparing for climate-related disasters in Japan. UCL Open Environ. 4, e053. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444/ucloe.000053 (2022).

Kates, R. W., Colten, C. E., Laska, S. & Leatherman, S. P. Reconstruction of New Orleans after hurricane Katrina: A research perspective. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 14653–14660. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0605726103 (2006).

Iwasaki, K. Damage, living environment, and reconstruction under the Great East Japan Earthquake. The 6th Survey of Nuclear Disaster Evacuees from Futaba, Fukushima, summary of results 2020. NLI Research Institute. https://www.nli-research.co.jp/report/detail/id=68303?pno=2&site=nli (2021).

Imamura, F. Mini special issue on establishment of interdisciplinary research cluster of disaster science. J. Disaster Res. 14, 1317. https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2019.p1317 (2019).

Okuyama, J. et al. WBF-2019 core research cluster of disaster science planning session as disaster preparedness: Participation in a training program for conductor-type disaster healthcare personnel. J. Disaster Res. 15, 900–912. https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2020.p0900 (2020).

Okuyama, J. et al. Establishment of a post-disaster healthcare information booklet for the Turkey-Syrian earthquake, based on past disasters. Sci. Rep. 14, 1558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52121-4 (2024).

Delaney, A. Setting Nets on Troubled Waters: Environment, Economics, and Autonomy among Nori Cultivating Households in a Japanese Fishing Cooperative. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh (2003).

Plaza, G., Katayama, S. & Omori, M. Spatiotemporal patterns of parturition of the black rockfish Sebastes inermis in Sendai Bay, Northern Japan. Fish. Sci. 70, 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1444-2906.2003.00799.x (2004).

Kunii, Y. et al. Review of mental health consequences of the Great East Japan earthquake through long-term epidemiological studies: The Shichigahama health promotion project. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 257, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.2022.J039 (2022).

Suzuki, T. et al. Impact of type of reconstructed residence on social participation and mental health of population displaced by disasters. Sci. Rep. 11, 21465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00913-3 (2021).

Akaishi, T. et al. Five-year psychosocial impact of living in postdisaster prefabricated temporary housing. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.214 (2021).

Tomita, H. A Study on the Changes in the Health Status of Disaster Victims in Shichigahama Town. Survey on the Health Status of the Victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in Miyagi Prefecture, FY2019 Summary and Subcommittee Research Report. Subsidy for Health and Labor Administration Promotion Research Project (Health Safety and Crisis Management Measures Comprehensive Research Project), 90–98 (2020).

Hamaie, Y., Kunii, Y. & Tomita, H. Anxiety-related symptoms, anxiety reactions, and coping strategies during disasters. Jpn J. Clin. Psychiatry 51, 989–996 (2022).

Fairbrother, G., Stuber, J., Galea, A., Fleischman, A. & Pfefferbaum, B. Posttraumatic stress reactions in New York city children after the september 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Ambul. Pediatr. 23, 304–311 (2003).

Bugge, I. et al. Physical injury and posttraumatic stress reactions. A study of the survivors of the 2011 shooting massacre on Utøya Island. Nor. J. Psychosom. Res. 79, 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.005 (2015).

Matsubara, C. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for post-traumatic stress reaction among resident survivors of the tsunami that followed the Great East Japan earthquake, March 11, 2011. Disaster Med. Public Health. Prep. 10, 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2016.18 (2016).

Okuyama, J., Funakoshi, S., Tomita, H., Yamaguchi, T. & Matsuoka, H. School-based interventions aimed at the prevention and treatment of adolescents affected by the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake: A three-year longitudinal study. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 242, 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.242.203 (2017).

Weiss, D. S. & Marmar, C. R. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD (eds Wilson, J. P. & Keane, T. M.) (Guilford Press, 1997).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 (2003).

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory 4th edn. (SAGE Publications Inc, 2015).

Harrison, S. E., Potter, S. H., Prasanna, R. & Doyle, E. E. H. ‘Sharing is caring’: A socio-technical analysis of the sharing and governing of hydrometeorological hazard, impact, vulnerability, and exposure data in Aotearoa New Zealand. Prog. Disaster Sci 13, 100213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2021.100213 (2022).

Mullen, P. D. & Reynolds, R. The potential of grounded theory for health education research: Linking theory and practice. Health Educ. Monogr. 6, 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817800600302 (1978).

Phillips, L. R. & Rempusheski, V. F. Caring for the frail elderly at home: Toward a theoretical explanation of the dynamics of poor quality family caregiving. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 8, 62–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198607000-00008 (1986).

Kato, A. Implications of fault-valve behavior from immediate aftershocks following the 2023 Mj6 5 earthquake beneath the Noto Peninsula. Central Jpn. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106444. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL106444 (2024).

Flicker, S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the positive youth project. Health Edu. Behav. 35, 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198105285927 (2008).

Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J. & Parker, E. A. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, 2nd edition (Springer, 2012).

Lekakis, S., Shakya, S. & Kostakis, V. Bringing the community back: A case study of the post-earthquake heritage restoration in Kathmandu valley. Sustainability 10, 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082798 (2018).

Tiwari, S. R. Community Participation in Heritage Affairs in Revisiting Kathmandu: Safeguarding Living Urban Heritage 189–197 (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2013).

Li, Y. et al. Community health needs assessment with precede-proceed model: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 9, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-181 (2009).

Velonis, A. J. et al. ‘One program that could improve health in this neighbourhood is ____?’ using concept mapping to engage communities as part of a health and human services needs assessment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2936-x (2018).

Crankshaw, T. L. et al. ‘As we have gathered with a common problem, so we seek a solution’: Exploring the dynamics of a community dialogue process to encourage community participation in family planning/contraceptive programs. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 710. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4490-6 (2019).

Springer, M. V. & Skolarus, L. E. Community-based participatory research. Stroke 50, e48–e50. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024241 (2019).

Minkler, M., Blackwell, A. G., Thompson, M. & Tamir, H. Community-based participatory research: Implications for public health funding. Am. J. Public Health 93, 1210–1213. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210 (2003).

Maltrud, K., Polacsek, M. & Wallerstein, N. Participatory evaluation work book for community initiatives (University of New Mexico, 1997).

Kreuter, M. W., Lezin, N. A. & Young, L. A. Evaluating community-based collaborative mechanisms: Implications for practitioners. Health Promot. Pract. 1, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/152483990000100109 (2000).

Minkler, M., Thompson, M., Bell, J. & Rose, K. Contributions of community involvement to organizational-level empowerment: The federal Healthy Start experience. Health Educ. Behav. 28, 783–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810102800609 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Shichigahama Town Hall in Miyagi Prefecture for their cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by Innovative Research Program on Suicide Countermeasure Grant Number JPSCIRS20220301.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: S.S., J.O., F.I.; Data cleaning: T.H., T.K.; Data analysis and interpretation: I.T., F.Y.; Drafting the article: S.S., J.O.: Critical revision of the article: M.T., I.K.; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the Affiliations. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seto, S., Okuyama, J., Iwasaki, T. et al. Linking affected community and academic knowledge: a community-based participatory research framework based on a Shichigahama project. Sci Rep 14, 19910 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70813-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70813-9