Abstract

Yoga is effective in binge eating disorder (BED) treatment, but it does not seem effective enough to improve low physical fitness. In contrast, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is effective in improving physical fitness but has never been studied in the context of BED. In the study, 47 young inactive females with mild to moderate BED were recruited and randomly assigned to a HIIT group (HIIT), a Yoga group (YG), or a control group (CG; age, 19.47 ± 0.74, 19.69 ± 0.874, and 19.44 ± 0.63 years; BMI, 21.07 ± 1.66, 21.95 ± 2.67, and 20.68 ± 2.61 kg/m2, respectively). The intervention groups participated in 8-week specific exercises, while the CG maintained their usual daily activity. Before and after the training, participants were evaluated for BED using the binge eating scale (BES) and for physical fitness. The obtained data were compared within groups and between groups, and a correlation analysis between BES and physical fitness parameters was performed. After the training, the YG presented significant improvements in BES (− 20.25%, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.408), fat mass (FM, − 3.13%, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.269), and maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max, 11.51%, p = 0.000, ηp2 = 0.601), whereas the HIIT showed significant improvements in body weight (BW, − 1.78%, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.433), FM (− 3.94%, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.285), and BMI (− 1.80%, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.428), but not in BES. Comparisons between groups revealed that both HIIT and YG had significantly higher VO2max levels than CG (HIIT 12.82%, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.088; YG: 11.90%, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.088) with no difference between HIIT and YG. Additionally, YG presented significantly lower BES than both HIIT (15.45%, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.03) and CG (11.91%, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.03). In conclusion, Yoga is an effective treatment for BED, but HIIT is not, despite its high efficacy in improving physical fitness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Binge eating disorder (BED) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating episodes which are not followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors1. The mean age of BED onset is between 20 and 25 years, and it is more common in women than men, with lifetime prevalences of 3.5% and 2.0%, respectively2. BED can occur in individuals who are normal-weight, overweight, and/or obese individuals, and it is generally associated with self-reported insufficient activity3.

Diet and cognitive behavior therapy are the most common treatments for BED4, yet individual susceptibility varies widely. People with BED are generally associated with inadequate physical activity and low physical fitness, often accompanies by depression and anxiety5. As a result, physical exercise has recently gained much attention for its potential benefits in improving both BED6 and physical fitness7,8. Yoga is a typical low- to moderate-intensity exercise9 that is scalable for many fitness levels and considered safe for special populations10. Yoga has been shown to significantly improve binge eating behaviors and reduce food preoccupation11,12. Recent studies have shown that Yoga could induce positive changes in various psychophysiological markers in individuals with obesity, alleviating physical limitations and chronic pain13,14. The influence of Yoga on BED is believed to be related to increased body awareness and body reactivity15. Consequently, Yoga has been preliminarily considered an additional treatment option in multimodal psychiatric treatment programs15. However, Yoga may be too low in intensity to improve physical fitness16 in individuals with BED, especially those with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is a form of high intensity physical exercise that involves repeated short bursts of intense exercise interspersed brief recovery periods17. Extensive evidence has shown the effectiveness of HIIT in improving physiological functions and physical fitness in both young and the elderly18, as well as in both healthy and sick individuals19. HIIT has also been shown to benefit appetite regulation20, promote spontaneous modulation of food choices, and regulate dietary intake21. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that HIIT might be helpful for individuals with BED in terms of both physical fitness and binge eating. However, evidence also suggests that moderate to vigorous physical activity is directly associated with increased food intake compared to general activity level22. This can perpetuate a cycle of binge eating and excessive exercise, contributing to overall physical and psychological distress.

Previous studies on overweight and obese adults have shown that HIIT could potentially offer comparable or greater benefits than moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in improving adherence, enjoyment, affective responses, quality of life, anxiety, and depression23. Yet, to our knowledge, no study to date has compared the effects of HIIT and Yoga on improving BED and physical fitness. The present study applied HIIT and Yoga in two groups of young inactive females with mild to moderate binge eating (BE). As the participants were young, with slightly lower physical fitness than average general and in the early stage of binge eating, we hypothesize that HIIT may be more effective than Yoga in improving physical fitness, such as body composition and aerobic capacity, and thereby reducing binge eating scores to a level comparable to that induced by Yoga. Thus, HIIT might be a potential alternative for the physical treatment of BE, comparable to Yoga.

Methods

Participants

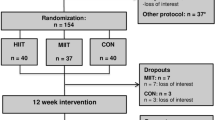

A total of 384 young female university students were recruited through campus posters. The reason of only including females in the study is that BED occurs more often in female than in male. The inclusion criteria were: (1) volunteer participation in the study; (2) a mild to moderate binge eating problem, defined as a binge eating score (BES) of 18 < BES < 27 (evaluated by a clinician); (3) the BE problem was not being treated by a clinical physician or psychiatrist; and (4) physically inactive, defined as metabolic equivalent minutes (MET) < 600 MET/week (assessed with an accelerometer, New Lifestyles NL-2000). The exclusion criteria were: (1) several binge eating problems, BES > 27 (7 students were excluded); (2) physically active, MET > 600 MET/week (272 students were excluded); (3) the binge eating problem was treated by a clinical physician or psychiatrist (10 students were excluded); (4) other acute or chronic diseases such as cardiorespiratory disease or diabetes (3 students were excluded); and (5) inability to complete the study (45 students were excluded).

According to Cohen classification, effect size (d) of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 is medium, and larger than 0.8 is large24. Additionally, according to Serdar25, the larger the effect size, the smaller the required sample size. In the present study, a medium effect size of 0.52 was selected to achieve a medium sample size, which was deemed appropriate considering both the time-consuming process of recruiting enough participants and financial constraints, as well as ensuring statistical reliability in the outcomes. Accordingly, with the effect size of 0.52, a calculated sample size of 39 with α = 0.05 and power = 0.8 was obtained. Ultimately, 47 individuals completed the study, exceeding the calculated sample size.

Using a R software (version 4.0.0, https://www.r-project.org/), the 47 participants were randomly assigned to the HIIT group (HIIT, n = 15), the Yoga group (YG, n = 16), and the control group (CG, n = 16, Table 1). Anthropology data of the participants, including height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), and BES as well as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) were measured and statistically analyzed. No significant difference was observed in any parameter between the groups.

This study was approved by the local Sports Science Experimental Ethics Committee at Beijing Sport University (BSU2021170H) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the participants provided their written informed consent, and the privacy of the participants was guaranteed.

Experimental procedures

The total experimental period was 11 weeks, and the procedures are shown in Table 2. In the first week, BES and physical activity level were evaluated, followed in the second week by measurements of the basic biometric data of all the participants, including height, body weight, body composition, BMI, fat mass, and VO2max. During 3–10 week, the HIIT and Yoga training programs were conducted. Participants were instructed to avoid participating in any forms of regular physical exercise for three months prior to the study. During the last week (week 11), biometric tests, BES, and VO2max were repeated for all participants.

Measurements

BES test: the test was conducted using the website of https://psychology-tools.com/binge-eating-scale/ in a quiet room. The BES was developed by Gormally26 and consists of 16 items, each with 3 to 4 options. Each option is assigned a score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 (0 indicates that there is no binge eating problem, 3 reflects a severe binge eating problem). The total score of the scale ranges from 0 to 46, with a higher total score indicating more severe in binge eating problems. No binge eating was defined as a BES score ≤ 17, mild to moderate binge eating as a BES score between 18 and 26, and severe binge eating as a BES score of 27 or higher27.

MET test: Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) level or activity level was evaluated over 6 consecutive days using an accelerator (New Lifestyles NL-2000, USA), worn for no less than 10 h per day from the moment of waking until going into bed, except during swimming and bathing. Participants needed to have an activity level of less than 600 MET.

Biometric test: the participants’ height was measured using a stadiometer (Jianmin, China), body weight was measured using a weight scale (Jianmin, China), and BMI was calculated as body weight/height2 (kg/m2). Body composition was measured using the dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar iDXA, GE Healthcare, USA). Weight and body composition measurements were performed in the morning after overnight fasting.

VO2max test: the test was conducted on a treadmill (H/P/Cosmos, Germany) with a Meta Max3B gas metabolism meter (Cortex, Germany). Participants followed a Modified Bruce protocol, and the test was stopped when any three of the four following criteria (exhaustion criteria)28 were met: (1) O2 uptake reached a plateau despite increased workload; (2) respiratory exchange ratio ≥ 1.15; (3) HR within ± 5% of age-predicted maximum (207–0.7 × age), and (4) inability to continue exercising.

Interventions

HIIT module: the participants engaged in treadmill training under the supervision of an exercise physiologist. The HIIT protocol began with a 5-min regular warm-up, followed by four repetitions of 3 min of brisk running at 90% VO2max intensity with 2 min of active recovery at 50% VO2max, and 5 min of cooling down between repetitions, totally about 30 min per day29. Participants were instructed to avoid any form of aerobic exercise outside of the specific exercise intervention. HIIT was conducted three times a week for 8 weeks.

Yoga module: Yoga practice was conducted under the instruction of two professional Yoga instructors. Each session lasted 60 min and was held three times a week. A session consisted of 5 min of meditation and breathing, 45 min of asanas, and 10 min of relaxation. If participants were unable to perform a specific pose, they were allowed to perform a similar but easier pose. Details of the Yoga practice are shown in Table 3.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, V.25.0, IBM Corporation, USA). Comparisons of variables before training between groups were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA).Body composition, VO2max, and BES were analyzed using 2 (Time: pre- and post-) × 3 (Conditions: HIIT, YG, and CG) repeated measures analysis of variance. Effect sizes were calculated for Time (M post-test − M pre-test/Pooled SD) and Condition (MYG − MHIIT/Pooled SD post-test; MYG − MCG/Pooled SD post-test; MHIIT − MCG/Pooled SD post-test). Correlation analyses were conducted using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to explore the relationship between BES and other parameters. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean (standard deviation) and/or ranges (minimum - maximum). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

After the specific training, the YG group presented significantly lower BES [F (2, 10.323) = 7.112, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.408] and fat mass [F (2, 5.525) = 3.025, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.269], whereas the group HIIT showed significant reductions in all three parameters of body composition, including body weight [F (2, 10.692) = 2.973, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.433], fat mass [F (2,5.598) = 3.025, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.285], and BMI [F (2, 10.486) = 3.011, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.428], but not in BES (Table 4). Additionally, after the training, both groups showed significant improvements in VO2max [HIIT: F (2, 37.646) = 10.666, p = 0.000, ηp2 = 0.729; YG: F (2, 22.588) = 10.666, p = 0.000, ηp2 = 0.601]; however, no significant difference was observed in VO2max between the two groups post training (Table 4).

Comparisons between groups revealed that the YG group had significantly lower BES scores than both the HIIT group [F (2, 44) = 3.829, p = 0.020, ηp2 = 0.030] and the CG group [F (2 ,44) = 3.829, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.030], whereas the HIIT group showed no significant difference in BES scores compared with the CG group. Moreover, no significant difference was observed in any parameter of body composition between the HIIT and YG groups (Table 4). Correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation only between BES and body weight in the HIIT group (r = 0,692, p = 0.004; Table 5).

Discussion

The study, for the first time, evaluated the effects of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on improving BED and physical fitness in young inactive females and compared these effects with those of Yoga. The results showed that while HIIT did not induce significant improvement in BED, it did significantly improve physical fitness. In contrast, Yoga led to significant improvements in both BED and VO2max. These results indicate that Yoga is an optimal treatment for BED, most likely through psychiatric regulation, whereas HIIT was not effective in improving BED through physical fitness, even in young females with mild to moderate BED.

HIIT is a time-efficient strategy that elicits physiological and psychological adaptations linked to improved physical fitness and metabolic health, making it particularly effective for individuals with overweight and obesity. It improves body composition, glucose and lipid metabolism, blood pressure, and cardiorespiratory fitness30,31. Consistent with previous observation, the 8-week high-intensity interval training program in this study led to significant improvement in physical fitness (VO2max) and body composition, including reductions in body weight, fat mass, and BMI. Evidence has also suggested a relationship between BED and body mass index (BMI) and obesity in both clinical and non-clinical populations32,33. This relationship holds true even in young inactive females with mild to moderate BE, who often have slightly higher body weight, fat mass34, and BMI35, but lower VO2max36 compared to age-matched healthy girls. HIIT has been shown to improve body composition in both healthy and BED patients37,38.

However, despite the significant improvement in physical fitness observed in this study, HIIT did not lead to a corresponding improvement in BED. Additionally, correlation analysis revealed that in the HIIT group, BES did not present significant correlation with most physical fitness parameters. These results suggest that BED cannot be rectified solely through improvement in physical fitness. This may be due to the adverse effects of HIIT on eating habits, as vigorous physical activity is directly associated with binge eating and increased appetite. Previous study, have indicated that while high-intensity exercise can increase energy expenditure and improve metabolic health, potentially aiding in weight management (a concern for individuals with BED39), HIIT does not to induce compensatory increase in energy intake compared to moderate-intensity exercise40.

Evidence has shown that high-intensity exercise is associated with mood improvements and reductions in depressive symptoms, common co-occurring factors in BED41. Intense physical activity can serve as a stress-relieving outlet, potentially reducing the likelihood of using binge eating as a coping mechanism for stress and negative emotions42. However, this study revealed that HIIT did not significantly improve BED. Although psychiatric parameters such as mood, self-esteem, self-image, depression, binge eating frequency were not individually evaluated, self-image and food intake behavior were assessed through the integrative BES parameter. In the HIIT group, BES was only significantly correlated with body weight and not with any other physical fitness parameter. These results indicate that high-intensity interval training did not function as a stress- or depression-relieving outlet in this context.

The 8-week Yoga intervention significantly improved BED, consistent with previous studies where Yoga led to significant reductions in BES43 and the frequency of binge eating episodes12. Individuals with BED are often accompanied by anxiety, depression, and guilt44,45, and low- to moderate intensity physical exercise has been shown to reduce the severity of anxiety and depression46,47. Yoga is believed to enhance body awareness, body image, body connection, and other aspects that are particularly helpful in reducing binge eating48. In this study, despite significant improvement in BES and a reduction in fat mass, no significant correlation was observed between BES and any physical fitness parameter. These results suggest that the significant improvement in BES induced by Yoga, a typical low- to moderate intensity exercise, is not associated with physical fitness improvement but with psychiatric regulation. However, the study did not demonstrate a direct correlation between BES and fat mass or any other physiological parameters in the Yoga group, reinforcing the notion that BED is primarily a psychiatric disorder15.

Conclusions

This present study revealed that HIIT cannot effectively improve binge eating, while Yoga can. In contrast, Yoga only induced significant improvement in VO2max, whereas HIIT significantly improved all physical fitness parameters. We concluded that Yoga, rather than HIIT, is the optimal physical treatment for the psychiatric disorder of BED.

Limitations

The interpretation of the current results should be approached with caution due to several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small, and the participants were limited to young inactive young females. Secondly, the 8-week physical training may not capture long-term training effects. Additionally, the study did not include diet control, which could be a confounding factor. Finally, the study did not assess mood along with BED symptoms, making it difficult to fully interpret some results, particularly the findings of the correlation analysis between BED and body composition. Future research should include a more diverse sample, extend the training period, use objective measures of dietary intake and physical activity, and assess mood to further examine the risks and potential benefits of HIIT for BED, the conditions for its application, even the possibility of combining Yoga with other therapeutic interventions for a holistic approach to managing BED.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request ([email protected]).

Change history

05 November 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78279-5

References

Ágh, T. et al. Epidemiology, health-related quality of life and economic burden of binge eating disorder: a systematic literature review. Eat. Weight Disord. 20, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0173-9 (2015).

Kornstein, S. G. Epidemiology and Recognition of Binge-Eating Disorder in Psychiatry and Primary Care. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 78 (Suppl 1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.sh16003su1c.01 (2017).

Freizinger, M. et al. Binge-eating behaviors in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Eat. Disord. 10, 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00650-6 (2022).

Hilbert, A. Psychological and medical treatments for binge-eating disorder: a research update. Physiol. Behav. 269, 114267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2023.114267 (2023).

Guerdjikova, A. I., Mori, N., Casuto, L. S. & McElroy, S. L. Update on binge eating disorder. Med. Clin. North. Am. 103, 669–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2019.02.003 (2019).

Raisi, A. et al. Treating binge eating Disorder with Physical Exercise: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 55, 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2023.03.010 (2023).

Galasso, L. et al. Binge eating disorder: what is the role of physical activity associated with dietary and psychological treatment? Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123622 (2020).

Batrakoulis, A. Psychophysiological adaptations to Pilates training in overweight and obese individuals: a topical review. Diseases. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases10040071 (2022).

Sivaramakrishnan, D. et al. The effects of yoga compared to active and inactive controls on physical function and health related quality of life in older adults- systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 16, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0789-2 (2019).

Newsome, A. N. M. et al. ACSM worldwide fitness trends: Future directions of the health and fitness industry. ACSM’s Health Fitness J. 28, 14–26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1249/fit.0000000000000933 (2024).

Carei, T. R., Fyfe-Johnson, A. L., Breuner, C. C. & Brown, M. A. Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. J. Adolesc. Health. 46, 346–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007 (2010).

Brennan, M. A., Whelton, W. J. & Sharpe, D. Benefits of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders: results of a randomized controlled trial. Eat. Disord. 28, 438–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1731921 (2020).

Batrakoulis, A. Role of mind-body fitness in obesity. Diseases. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11010001 (2022).

Batrakoulis, A. Psychophysiological adaptations to yoga practice in overweight and obese individuals: a topical review. Diseases. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases10040107 (2022).

Ostermann, T., Vogel, H., Boehm, K. & Cramer, H. Effects of yoga on eating disorders—A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 46, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.07.021 (2019).

Csala, B., Szemerszky, R., Körmendi, J., Köteles, F. & Boros, S. Is weekly frequency of yoga practice sufficient? Physiological effects of Hatha yoga among healthy novice women. Front. Public. Health. 9, 702793. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.702793 (2021).

MacInnis, M. J. & Gibala, M. J. Physiological adaptations to interval training and the role of exercise intensity. J. Physiol. 595, 2915–2930. https://doi.org/10.1113/jp273196 (2017).

Stern, G., Psycharakis, S. G. & Phillips, S. M. Effect of high-intensity interval training on functional movement in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open. 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-023-00551-1 (2023).

Lock, M., Yousef, I., McFadden, B., Mansoor, H. & Townsend, N. Cardiorespiratory fitness and performance adaptations to high-intensity interval training: are there differences between men and women? A systematic review with Meta-analyses. Sports Med. 54, 127–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01914-0 (2024).

Sim, A. Y., Wallman, K. E., Fairchild, T. J. & Guelfi, K. J. Effects of high-intensity intermittent exercise training on appetite regulation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 47, 2441–2449. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000687 (2015).

Donati Zeppa, S. et al. High-intensity interval training promotes the shift to a health-supporting dietary pattern in young adults. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030843 (2020).

Martinez-Avila, W. D. et al. Eating behavior, physical activity and exercise training: a randomized controlled trial in young healthy adults. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123685 (2020).

Batrakoulis, A. & Fatouros, I. G. Psychological adaptations to high-intensity interval training in overweight and obese adults: a topical review. Sports (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10050064 (2022).

Cohen, J. Things I have learned (so far). Am. Psychol. 45, 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.12.1304 (1990).

Serdar, C. C., Cihan, M., Yücel, D. & Serdar, M. A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 31, 010502. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2021.010502 (2021).

Gormally, J., Black, S., Daston, S. & Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 7, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7 (1982).

Marcus, M. D., Wing, R. R. & Hopkins, J. Obese binge eaters: affect, cognitions, and response to behavioural weight control. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 56, 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.3.433 (1988).

Prasad, V. K. et al. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness and submaximal systolic blood pressure among young adult men: a reversed J-curve pattern relationship. J. Hypertens. 33, 2239–2244. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000000715 (2015).

Mathisen, T. F. et al. The PED-t trial protocol: the effect of physical exercise -and dietary therapy compared with cognitive behavior therapy in treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 17, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1312-4 (2017).

Batrakoulis, A. et al. Comparative efficacy of 5 Exercise types on cardiometabolic Health in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis of 81 randomized controlled trials. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 15, e008243. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.121.008243 (2022).

Batrakoulis, A., Jamurtas, A. Z. & Fatouros, I. G. High-intensity interval training in metabolic diseases: physiological adaptations. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 25, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1249/fit.0000000000000703 (2021).

Mustelin, L., Bulik, C. M., Kaprio, J. & Keski-Rahkonen, A. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder related features in the community. Appetite. 109, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.032 (2017).

Duncan, A. E., Ziobrowski, H. N. & Nicol, G. The prevalence of past 12-month and lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders by BMI category in US men and women. Eur. Eat. Disord Rev. 25, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2503 (2017).

Database, N. P. F. A. H. http://cnphd.bmicc.cn/chs/cn/

(MOE), M. O. E. National Physical Fitness Standards for Students (Revised 2014). (2014).

Zehao, W. A Study on Cardiorespiratory Function of Non-physical Education Students—Regression Equation for Predicting Maximal Oxygen Uptake (Shandong Institute of P.E. and Sports, 2023).

Hu, M. et al. Interval training causes the same exercise enjoyment as moderate-intensity training to improve cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in young Chinese women with elevated BMI. J. Sports Sci. 39, 1677–1686. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1892946 (2021).

Guo, L., Chen, J. & Yuan, W. The effect of HIIT on body composition, cardiovascular fitness, psychological well-being, and executive function of overweight/obese female young adults. Front. Psychol. 13, 1095328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1095328 (2022).

Davis, C. A. et al. Dopamine for wanting and opioids for liking: a comparison of obese adults with and without binge eating. Obes. (Silver Spring). 17, 1220–1225. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.52 (2009).

Taylor, J. L. et al. High intensity interval training does not result in short- or long-term dietary compensation in cardiac rehabilitation: results from the FITR heart study. Appetite. 158, 105021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105021 (2021).

Herring, M. P., O’Connor, P. J. & Dishman, R. K. The effect of exercise training on anxiety symptoms among patients: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 170, 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.530 (2010).

Vancampfort, D. et al. Type 2 diabetes among people with posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 78, 465–473. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000297 (2016).

McIver, S., O’Halloran, P. & McGartland, M. Yoga as a treatment for binge eating disorder: a preliminary study. Complement. Ther. Med. 17, 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2009.05.002 (2009).

Peterson, R. E., Latendresse, S. J., Bartholome, L. T., Warren, C. S. & Raymond, N. C. Binge Eating Disorder Mediates Links between Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Caloric Intake in Overweight and Obese Women. J Obes 407103, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/407103 (2012).

Bittencourt, S. A., Lucena-Santos, P., Moraes, J. F. & Oliveira Mda, S. Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with and without binge eating disorder enrolled in weight loss programs. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 34, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1590/s2237-60892012000200007 (2012).

Jackson, M., Kang, M., Furness, J. & Kemp-Smith, K. Aquatic exercise and mental health: a scoping review. Complement. Ther. Med. 66, 102820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102820 (2022).

Mohammad, A. et al. Biological markers for the effects of yoga as a complementary and alternative medicine. J. Complement. Integr. Med.https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2018-0094 (2019).

Borden, A. & Cook-Cottone, C. Yoga and eating disorder prevention and treatment: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Eat. Disord. 28, 400–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1798172 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Lu Guo from School of Psychology at Beijing Sport University for her statistical support. This work was supported by the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (Grant Numbers: 2015YB001, 2024JNPD001) and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Number: 2022YFC3600201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: HML, CJL, CQY, JGY and SSM. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: HML, CJL, YHS, JGY and SSM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: HML, CJL. Administrative, technical, or material support: LZ, CQY and SSM. Study supervision: SSM.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article was incomplete. It now reads: We would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Lu Guo from School of Psychology at Beijing Sport University for her statistical support. This work was supported by the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (Grant Numbers: 2015YB001, 2024JNPD001) and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Number: 2022YFC3600201).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, HM., Liu, CJ., Shen, YH. et al. High-intensity interval training vs. yoga in improving binge eating and physical fitness in inactive young females. Sci Rep 14, 22912 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74395-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74395-4