Abstract

Evidence shows that inflammatory responses play an essential role in the development of brain metastases (BM). The goal of this meta-analysis was to critically evaluate the literature regarding the use of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) to predict the prognosis of patients with BM to help clinicians institute early interventions and improve outcomes. We conducted systematic review and meta-analysis, utilizing data from prominent databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases. Our inclusion criteria encompassed studies investigating the studies that assessed the association between NLR and overall survival (OS). We included 11 articles, with 2629 eligible patients, to evaluate the association between NLR and OS. High NLR was significantly associated with shorter OS, with a pooled hazard ratio (HR) of 1.82 (95% CI 1.57–2.11). Subgroup analysis revealed that this association was consistent across different regions, with HRs of 2.03 (95% CI 1.67–2.46) in Asian populations and 1.58 (95% CI 1.35–1.84) in non-Asian populations. Additionally, in a subgroup analysis based on NLR cut-off values, patients with NLR ≥ 3 had an HR of 1.69 (95% CI 1.46–1.96), while those with NLR < 3 had an HR of 2.26 (95% CI 1.64–3.11). Sensitivity analysis confirmed that no single study significantly influenced the pooled effect size. Our meta-analysis confirmed the prognostic value of NLR in patients with brain metastasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain metastases (BM) represent the most prevalent form of central nervous system neoplasms in adult1, and their incidence is progressively increasing2. Treatment of BM ranges from supportive care to multimodal strategies considering surgery, fractioned radiotherapy, whole brain radiotherapy, stereotactic radiosurgery, or chemotherapy3,4,5. Despite advancements in treatment modalities, the prognosis for patients with BM remains grim3, underscoring the critical need for reliable prognostic markers to guide therapeutic decision-making and improve patient outcomes. Existing prognostic models, such as radiation therapy oncology group–recursive partitioning analysis, score index for radiosurgery, basic score for brain metastasis, and graded prognostic assessment, offer valuable insights but are not without limitations, often due to subjective scoring elements that introduce uncertainty6,7

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) emerges as a potential objective marker, routinely collected in clinical settings, that could overcome the subjectivity associated with traditional model8. Although prior meta-analyses have explored the prognostic value of NLR in lung cancer8 patients with BM, its applicability across other cancer types remains less understood. Our study aims to comprehensively assess the association between pre-treatment NLR and overall survival (OS) in patients with BM from various cancer origins, offering updated insights into its prognostic utility.

Materials and methods

Literature search

Articles on the prognostic significance of preconditioning NLR in cancer patients with BM were searched from the establishment of PubMed, the Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases until January 20, 2024. This systematic review was not prospectively registered due to time constraints. Despite the time limitations, we have conducted this review with rigorous methodology. Searches were conducted using the following keywords: brain metastasis, BM, leptomeningeal metastasis, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil/lymphocyte. Two investigators performed the search without mutual communication. When disagreements arose, a third reviewer discussed and made a final decision.

Selection criteria

A study was included if it met the following criteria: studies in patients with cancer with a clinical or histological diagnosis of BM; studies that assessed the association between NLR and OS; studies in which NLR, and their cut-off values were adequately and accurately defined; and NLR values must be recorded at the time of BM diagnosis or within one month prior to initial treatment, including any form of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery.

The following studies were excluded: (1) case reports, letters, conference abstracts, non-clinical studies, and reviews without available data; (2) duplicated publications; and (3) studies with insufficient information to evaluate Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Data extraction

A standardized form was used to extract the following information from the included studies: first author, sample size, average age, sex distribution, NLR cut-off values, cancer type, and outcome measures (e.g., HR and 95% CI). When available, we extracted the explicitly stated HR and 95% CI from each study.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

To ascertain the stability of our meta-analysis findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by sequentially excluding each study and recalculating pooled HRs and heterogeneity (I2). This allowed us to assess the influence of individual studies on the overall results. Stability was confirmed if no single study’s removal significantly altered the pooled HR or markedly affected heterogeneity.

Additionally, to explore the potential impact of different NLR cut-off values on prognostic outcomes, we conducted a subgroup analysis. Studies were divided into two groups based on their NLR cut-off values: NLR < 3 and NLR ≥ 3. For each subgroup, we calculated the pooled hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity within subgroups was assessed using the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test. The statistical significance of differences between subgroups was evaluated using a test for subgroup differences.

To address the potential impact of tumor heterogeneity, we also performed a subgroup analysis based on cancer types. Studies were categorized into two groups: “lung cancer only,” which included studies exclusively on lung cancer patients, and “mixed cancer types,” which included studies on patients with various types of cancer. For each subgroup, we calculated the pooled HR and its 95% CI. Heterogeneity within subgroups was assessed using the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test. The test for subgroup differences was employed to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between these two cancer type groups.

Statistical analysis

We used Review Manager software (version 5.4) for statistical analysis. The HR and its associated 95% CI were used as statistical effect size. Heterogeneity was tested using the Q-test and I2 statistics before the meta-analysis. When P > 0.1 or I2 < 50%, and heterogeneity was deemed insignificant, a fixed-effects model was applied for the analysis. When P ≤ 0.1 or I2 > 50%, significant heterogeneity was deemed to be present in the incorporated studies, a random-effects model was applied for the analysis. When significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, we conducted sensitivity analyses by sequentially excluding studies and performing subgroup analyses based on NLR cutoff values, as well as comparing Asian and non-Asian regions, to identify potential sources.

To accurately represent the demographic characteristics of the included studies, we calculated a weighted average for variables such as patient age. This weighted average was derived by accounting for the sample sizes of each individual study, providing a more precise summary of the overall population. By incorporating this approach, we aimed to minimize potential bias introduced by disproportionate sample sizes and ensure a robust representation of the study population.

Result

Literature selection results

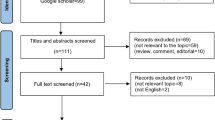

Based on the search strategy, 114 articles were identified. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 83 articles were excluded due to literature type, duplicate publications, unclear diagnosis, and poor relevance. After full-text screening, 20 articles were further excluded due to data unavailability. A total of 11 article 1,2,3,4,5,9,10,11,12,13,14 involving 2629 cases were included (Fig. 1). Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of the included studies. The included studies, published between 2017 and 2022, had sample sizes ranging from 65 to 1250 patients, with average ages between 52.7 and 67 years. They investigated the prognostic value of pre-treatment NLR in various cancers, with NLR cutoff values ranging from 2.43 to 7. The studies reported hazard ratios (HRs) for NLR ranging from 1.53 (95% CI 1.03–2.26) to 5.16 (95% CI 1.43–18.63).

Results of meta-analysis

Eleven studies reported on the association between NLR and OS among patients with BM from cancer, and a random-effects model was employed for analysis. The HR was 1.82 (95% CI 1.57–2.11, P < 0.001), suggesting a statistically significant association between NLR and OS in cancer patients with BM (Fig. 2).

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

The results for publication bias are shown in Fig. 3. The funnel plot does not exhibit apparent bias.

The sensitivity analysis involved sequentially removing individual studies, and the results are shown in Table 2. This analysis indicated that the overall HRs remained consistent, with a fixed-effect model value of 1.67 (95% CI 1.52–1.84) and an I2 value of 22%. The HRs after excluding individual studies ranged from 1.72 (95% CI 1.52–1.94) to 1.95 (95% CI 1.65–2.31), with I2 values ranging from 0 to 28%. These results suggest that the heterogeneity among the studies remained low to moderate, indicating the robustness of our meta-analysis results.

Subgroup analysis was conducted to further investigate the relationship between NLR and OS. The results suggested that patients with high NLR had shorter OS in both Asian and non-Asian populations, although a significant difference between the two regions indicates a potential regional influence (Fig. 4).

Additionally, a subgroup analysis based on NLR cut-off values (NLR < 3 vs. NLR ≥ 3) was performed to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. For NLR ≥ 3, the combined HR was 1.69 (95% CI 1.46–1.96) with an I2 value of 17%. For NLR < 3, the combined HR was 2.26 (95% CI 1.64–3.11) with an I2 value of 0%. The overall combined HR for all studies was 1.82 (95% CI 1.57–2.11) with an I2 value of 19% (Fig. 5). For the “lung cancer only” subgroup, the combined HR was 2.28 (95% CI 1.82–2.86) with an I2 value of 0%. For the “mixed cancer types” subgroup, the combined HR was 1.56 (95% CI 1.40–1.74) with an I2 value of 0%. The test for subgroup differences showed a significant difference (P = 0.003) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In this study, we scrutinized eleven studies that aligned with our inclusion criteria. Our meta-analysis revealed a significant association between elevated NLR and reduced OS in cancer patients with BM.

NLR is widely recognized as a prognostic marker in various cancers, as it reflects systemic inflammation that promotes tumor progression15. In patients with brain metastases, elevated NLR may have an especially strong prognostic impact due to the unique immune environment of the brain. This underscores NLR’s relevance across different cancer types while highlighting its specific significance in the context of brain metastases. Our findings are consistent with previous studies, which have identified inflammation, represented by NLR, as a critical factor in cancer progression and metastasis. Elevated NLR may reflect a systemic inflammatory response that fosters tumor growth and treatment resistance, leading to poorer patient outcomes16,17.

Previous meta-analyses have primarily focused on the prognostic value of NLR in patients with BM from lung cancer8. But these studies did not fully explore the implications of NLR for patients with BM from other cancer types, which limits the generalizability of their conclusions. Our meta-analysis addresses this gap by including a broader spectrum of cancers, such as breast, gastrointestinal, and renal cancers, offering a more comprehensive understanding of NLR’s prognostic significance. Furthermore, by incorporating recently updated data, we provide more current and robust insights. This allows our study to demonstrate the potential of NLR as a widely applicable biomarker, enhancing its relevance across various cancer types.

In our study, there are some limitations. First, detailed information of unknown pretreatment (i.e., physical conditions, comorbidities, infective symptoms, medication, hypertension, lifestyle habits, and diabetes mellitus) could influence the NLR value, thus weakening its actual relationship with cancer-specific endpoints. Second, the NLR cut-off points differed in some studies and the purpose of their study was different, increasing the heterogeneity among studies and making the clinical application more difficult. Third, although no significant deviation was observed in the funnel plot, we did not identify any negative results.

Additionally, leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) and brain parenchymal metastasis (BPM) are associated with different prognostic outcomes, potentially due to variations in their underlying inflammatory mechanisms. While our meta-analysis did not specifically separate these two types of metastasis, some included studies grouped LM and BPM together, which could obscure differences in the prognostic value of NLR between them. Future research with more detailed stratification is needed to determine whether NLR has distinct significance in these subgroups.

Furthermore, existing prognostic models offer valuable insights but are not without limitations, often due to subjective scoring elements that introduce uncertainty. The accuracy of these models can vary, and our study demonstrates that NLR, a simpler and more objective marker, provides a reliable prognostic value for patients with BM. This suggests that NLR could complement existing models by adding a quantifiable and reproducible parameter, enhancing the overall prognostic accuracy and aiding in better patient management and treatment decisions.

The clinical relevance of our findings lies in the potential for physicians to use NLR as an auxiliary tool in prognostic evaluation, guiding treatment decisions. Patients with elevated NLR may benefit from more aggressive therapeutic approaches and closer monitoring to improve their prognosis. Furthermore, our results suggest potential areas for future research, such as examining the association of NLR with prognosis in different cancer types and treatment contexts, which may provide valuable insights for improving patient management. In summary, our study not only reinforces the value of NLR in assessing the prognosis of patients with BM but also provides clinicians with a useful marker for better managing and treating this patient group.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis confirmed the prognostic value of NLR in patients with BM. NLR could serve as a reliable prognostic indicator for unfavorable outcomes in patients with BM, with variations observed across different geographic regions and cancer types.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the PubMed, Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Change history

06 November 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78599-6

References

Cui, H. et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (preNLR) for the assessment of tumor characteristics in lung adenocarcinoma patients with brain metastasis. Transl. Oncol. 22, 101455 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Pre-stereotactic radiosurgery neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of the prognosis for brain metastases. J. Neurooncol. 147(3), 691–700 (2020).

Chowdhary, M. et al. Post-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts for overall survival in brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. J. Neurooncol. 139(3), 689–697 (2018).

Li, H. et al. The clinical prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer-Harboring EGFR mutations. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 5659–5665 (2020).

Picarelli, H. et al. The preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predictive value for survival in patients with brain metastasis. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 80(9), 922–928 (2022).

Paravati, A. J. et al. Radiotherapy and temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma and anaplastic astrocytoma: validation of radiation therapy oncology group-recursive partitioning analysis in the IMRT and temozolomide era. J. Neurooncol. 104(1), 339–349 (2011).

Nieder, C. & Mehta, M. P. Prognostic indices for brain metastases–usefulness and challenges. Radiat. Oncol. 4, 10 (2009).

Li ZW, Zhang S, Wu W. Prognostic Value of Pre-Treatment Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-To-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients With Brain Metastasis From Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.16.017

Starzer, A. M. et al. Systemic inflammation scores correlate with survival prognosis in patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases. Br. J. Cancer 124(7), 1294–1300 (2021).

Naresh, G. et al. Assessment of brain metastasis at diagnosis in non-small-cell lung cancer: A prospective observational study from North India. JCO Glob. Oncol. 7, 593–601 (2021).

Kasmann, L. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts outcome in limited disease small-cell lung cancer. Lung 195(2), 217–224 (2017).

Hong, Y. et al. Systematic immunological level determined the prognosis of leptomeningeal metastasis in lung cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 14, 1153–1164 (2022).

Doi, H. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival after whole-brain radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. In Vivo 33(1), 195–201 (2019).

Ren BX. Analysis of survival and prognostic factors of patients with brain metastases from lung cancer after whole brain radiotherapy [Master’s thesis]. Suzhou University, 2020. https://doi.org/10.27351/d.cnki.gszhu.2020.001838

Stefaniuk, P., Szymczyk, A. & Podhorecka, M. The neutrophil to lymphocyte and lymphocyte to monocyte ratios as new prognostic factors in hematological malignancies—A narrative review. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 2961–2977 (2020).

Kim, H. J. et al. Prognostic significance of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in neuroendocrine carcinoma. Chonnam Med. J. 58(1), 29–36 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Prognostic value of the pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in cervical cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Oncotarget 8(8), 13400–13412 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept: YZ. Design: KZ, JW, YL, YY, XJ, HL, QL, XY and SZ. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: KZ, YL, YY, XJ, HL and QL. Statistical analysis: YY, YL and KZ. Drafting of the manuscript: KZ and XJ. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Affiliation 1 and 2 were not listed in the correct order. The correct affiliations are listed here. Affiliation 1: Center for Evidence-Based Medicine, Clinical Research Center, Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China. Affiliation 2: School of Preclinical Medicine / School of Nursing, Chengdu University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China. Additionally, the original version of this Article omitted an affiliation for Ken Zhou.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, K., Wan, J., Li, Y. et al. Prognostic value of pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with brain metastasis from cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 14, 24789 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76305-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76305-0