Abstract

Accelerating sea level rise (SLR) and changing storm patterns will increasingly expose barrier islands to coastal hazards, including flooding, erosion, and rising groundwater tables. We assess the exposure of Cape Lookout National Seashore, a barrier island system in North Carolina (USA), to projected SLR and storm hazards over the twenty-first century. We estimate that with 0.5 m of SLR, 47% of current subaerial barrier island area would be flooded daily, and the 1-year return period storm would flood 74%. For 20-year return period storms, over 85% is projected to be flooded for any SLR. The modelled groundwater table is already shallow (< 2 m deep), and while projected to shoal to the land surface with SLR, marine flooding is projected to overtake areas with emergent groundwater. Projected shoreline retreat reaches an average of 178 m with 1 m of SLR and no interventions, which is over 60% of the current island width at narrower locations. Compounding these hazards is subsidence, with one-third of the study area currently lowering at > 2 mm/yr. Our results demonstrate the difficulty of managing natural barrier systems such as those managed by federal park systems tasked with maintaining natural ecosystems and protecting cultural resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

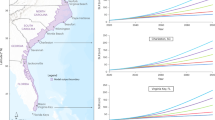

Sea level rise (SLR) poses a major threat to both the natural and built environment through increasing rates of coastal flooding, erosion, and shallow groundwater rise1,2,3. When storms occur in the future with elevated sea level, dynamic processes such as waves and storm surge will reach higher land elevations along the coast. Barrier islands, such as those that make up our study area, Cape Lookout National Seashore (CLNS) in North Carolina, U.S. (Fig. 1), buffer storm impacts for the mainland coast. However, the barrier islands themselves are at an increased risk compared to mainland coasts, as they can experience the hazards of SLR and storms on all sides. Vulnerable barrier islands can lead to more vulnerable mainland coastlines in the future4.

Map of study area. Panel (A) shows the current legislated area of Cape Lookout National Seashore (CLNS) in red. This boundary defines the extent of all data presented in this paper. Panel (B) shows rotated inset of boxed area shown in panel (A), with modeled flood results for the 0 m SLR, no storm case showing what we define as present day land (tan areas) and water (blue areas). Panel (C) shows sea level rise estimates from the U.S. Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flood Hazard Scenarios and Tools Interagency Task Force (Sweet et al., 2022), which projects higher than global rates of SLR for the study area (i.e., using the Beaufort tide gauge as a proxy) of 32–51 cm by 2050 and 54–210 cm by 2100. We created the maps using ESRI ArcMap 10.8.1 software http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

Global sea level has risen by 3.4 mm/yr during the satellite era (1993–2022)5 and the rate has increased by 29% to 4.4 mm/yr over the last decade (2013–2022)6, more than triple the 20th Century rate7. The U.S. East Coast north of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (just north of the study area) has been a hotspot for SLR, with a rate of increase 3–4 times higher than the global average from 1950–20098. South of Cape Hatteras, sea level also rose greater than 20 mm/yr from 2011–2015, linked to large-scale ocean dynamics such as the variability of the North Atlantic Oscillation9,10 and/or Florida current dynamics11,12. At the nearest tide gauge to CLNS, in Beaufort, North Carolina, the sea level has risen by 3.4 mm/yr from 1952–2022, with notable recent acceleration13. In line with higher observed rates along the North Carolina coast, the U.S. Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flood Hazard Scenarios and Tools Interagency Task Force projects higher than global rates of SLR for the study area (i.e., using the Beaufort, North Carolina, tide gauge as a proxy) of 32–51 cm by 2050 and 54–210 cm by 2100 (Fig. 1C). The observation-based projections in this ___location are currently following the intermediate-high emission scenario, which would yield a median SLR projection of 46 cm by 2050 and 160 cm by 210014.

Due to higher rates of SLR in the region, annual rates of high tide flooding have been increasing rapidly over the last several decades15 and are expected to increase by up to an order of magnitude by 205014. Recent hurricanes have had major impacts (i.e., extensive flooding, erosion, loss of habitats) on the region, including Matthew (2016), Florence (2018), and Dorian (2019). For coastal North Carolina, flood risk for extreme storm events doubles with just 5–10 cm of SLR16, and therefore, in the coming decades, hurricanes will likely cause more severe impacts than in the recent past.

Barrier islands can rapidly evolve in response to changing environmental conditions such as SLR and storms17. For example, barrier islands migrate landward as sea level rises, which can help these systems persist and thus continue protecting the mainland coasts behind them4,18. For developed barrier islands, natural responses are often managed to protect communities and infrastructure, but altering natural processes can be less sustainable for a barrier island in the long term4,19,20,21,22. On the barrier islands of CLNS—North Core Banks, South Core Banks, and Shackleford Banks (Fig. 1)—, natural processes such as island migration and overwash are typically allowed to occur23.

The many hazards that can arise from SLR and storms on CLNS, including flooding, groundwater rise, erosion, and island migration, make managing these islands challenging. There are numerous resources to manage on CLNS: e.g., historic villages, a historic (and still operational) lighthouse, camping facilities, ferry landings, and nesting and habitat areas for several federally protected and/or threatened species. Managers need the best possible long-term projections of potential changes from SLR and storms that affect their managed assets.

Study approach

To provide some of these long-term projections for CLNS, here we assess the exposure of this natural barrier island system (Fig. 1) to four different types of hazards: modeled projections of flooding, groundwater rise, and shoreline change caused by SLR and storms over the 21st Century, and vertical land motion from 14 years of historical observations. CLNS consists of the largely undeveloped barrier islands North Core Banks, South Core Banks, and Shackleford Banks, and the eastern end of developed Harkers Island (which is inland of the barrier islands and is not a barrier island), where the Visitor Center is located (Fig. 1). We show that the viability of this barrier island system will be compromised by increasingly severe flooding, rising groundwater, erosion, and land subsidence over the next century. As part of the National Park Service, these islands serve as a global proxy for a common coastal management dilemma in the face of significant present-day and future coastal hazards: protecting important cultural and archaeological resources while seeking to allow natural processes to continue, and/or favoring nature-based interventions for coastal sustainability.

The data used in this paper come from results from the Coastal Storm Modeling System (CoSMoS)24,25,26,27 approach and satellite observations applied to the U.S. Southeast Atlantic coast, which provide future coastal hazard data for the area from Norfolk, Virginia to Miami, Florida, from the coast to typically about 100 km inland to 10 m topographic elevation28,29. Thus, analyses like those presented in this paper could be performed along any other region in this area where this data is available, including along developed barrier island systems. The datasets used are available from Barnard et al.28 and detailed in the Data Availability section.

For each of the four hazards presented, we took the data for the full Southeast region and reduced it to just the data that falls within the boundaries of CLNS (Fig. 1, colored regions). Then we quantified areas and mapped patterns of the hazards within CLNS. The model results are presented for a range of SLR scenarios intended to encompass plausible projections by 2100 (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 3.0 m). The flood model projections also include a range of storm conditions across each SLR projection (no-storm, 1-year, 20-year, and 100-year return period storms). In this paper, we present results relative to SLR values, not time, to decouple the uncertainty of timing from future SLR. However, in the Discussion section, we relate results to time, using the SLR values closest to local estimates for the intermediate-high scenario for the years 2050 (0.46 m) and 2100 (1.60 m)14.

It is important to note that the four hazard projections are not coupled. That is, neither shoreline change nor vertical land motion results are applied to the topobathymetry or morphology for the other products; present-day topobathymetry is used for flooding and groundwater modeling. Island morphological profile changes, including changes in dune height, due to SLR or storm impacts are not modeled, thus only present-day topography and bathymetry are used. The assumption of static morphology within the flooding and groundwater models implies that their results are most pertinent in the shorter term or near the Visitor Center on developed Harkers Island (the non-barrier island) (Fig. 1), where static morphology is more likely.

However, morphology will inevitably change over time. In the longer term, as sea level rises more and storms occur on the elevated sea level, natural barrier islands tend to migrate landward, as our shoreline change results suggest, with overwash tending to build interior elevation30 while the overall offshore profile roughly preserves its shape. However, recent studies suggest that barrier island retreat rates do not necessarily increase monotonically with SLR, due to the role of storms and biophysical interactions31,32,33. Despite the general tendency of storms to increase interior elevations with sea level rise, storms can sometimes cause volume loss, as seen with sound-side inundation due to Hurricane Dorian (2019) that led to elevation and volume loss through extensive erosional washout channels on North Core Banks34. While the shoreline change results indicate the barrier islands will migrate landward in the projected wave/storm climate, we cannot speculate on the exact morphological changes that will occur on CLNS. Additionally, the land subsidence demonstrated in our vertical land motion results will decrease land elevations on which all these processes occur.

Thus, results show the best estimates using present-day morphology and clearly demonstrate the vulnerability of this barrier island system. Specific locations of flooding or change in groundwater table depths will not be exact in the longer-term future, when the barrier island locations and morphology will have evolved in ways that depend on the coupling between the islands and their backbarrier marshes, on the timing and intensity of storm flooding, overwash events, waves, and winds, on dune structure and grasses, and on relative SLR21,22,30,34,35,36, processes that were not accounted for in the models.

Individual details on the data used for each of the four hazards—overland flooding, groundwater depths, shoreline change, and vertical land motion—are provided in the Materials and Methods section and in cited references that go into greater detail. The CoSMoS modeling approach applied was initially developed for use in California, with some modifications made for the U.S. Southeast coast. For flood modeling, modifications account for tropical cyclones and compound flooding common to the region, including pluvial, fluvial, and oceanic drivers37,38,39. Shoreline change modeling follows the same approach as Vitousek et al.78 using local satellite-derived shoreline observations and modified to include a range of transgression slopes, as befitting the additional uncertainty of a passive coastal margin setting40. Here, we present only the intermediate slope. Vertical land motion is derived from synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites. While uncertainties are not presented in this paper, they are included with the source data and references. For example, for shoreline change, potential storm erosion uncertainty bands were made for the same storm return periods used in the flood modeling; and though vertical land motion is not included in the topobathymetry used for the models of the other three products, it was included as part of the total uncertainty in the flood modeling (neither are presented here). See Materials and Methods for more information.

Results

Overland flooding

Within the boundaries of CLNS (an area of approximately 171.1 km2, indicated in red in Fig. 1A), the overland flood model results for no SLR and no storm (present-day, non-storm conditions) define approximately 77.6 km2 as present-day land (tan areas in panel B) and the remaining 93.5 km2 as water (blue areas in Fig. 1B), indicating the extent of high tide during a spring tide. In the model, water covering the land can come from tides, storm surge, wave setup, precipitation, and/or SLR. Inundation is used here to refer to water covering the land due to the maximum extent of the sea level with high tides, for SLR with no storms. Intermittent flooding is due to storms41.

For the 27 other SLR and storm combinations modeled (other than the no SLR, no storm scenario), 25 result in over 50% of the present-day land area covered in water (Fig. 2). On CLNS, fall and winter low pressure systems combined with large high tides have been known to cause flooding of the ocean beach into the dunes and of the salt marsh into the backroad on the North and South Core Banks at least once per year, likely approaching 50% of the area of these islands (J. Altman, Supervisory Biologist, CLNS, personal communication, April 30, 2024). For the 20- and 100-year return period storms modeled, any SLR value, including present-day sea level (0 m SLR)—and thus, applying to present-day morphology for the 0 m SLR case—results in over 85% of the land being flooded during the storm. Hurricanes Dorian (2019) and Florence (2018) were seen to flood roughly 85% of the land, as the 20-year return period model estimates (J. Altman, Supervisory Biologist, CLNS, personal communication, April 30, 2024). Additionally, Sherwood34, supports this extensive flooding during Hurricane Dorian with the over 80 erosional washout channels observed stretching from the marsh to the ocean on the 36 km of North Core Banks. For the 20- and 100-year storms modeled with SLR of 1 m or more, over 96% of the present-day land is flooded.

Histogram of projected flooding plus ponding over land areas of Cape Lookout National Seashore for each sea level rise (SLR, colors) and storm return period (x-axis) modeled, shown in both percent of land area (left side y-axis) and land area (km2, right side y-axis). No value is shown for the 0 SLR, No Storm scenario because it is used to define land versus water areas within Cape Lookout National Seashore and thus floods 0% of the land.

As discussed in the Study Approach section, the flooding areas and locations may be different due to the evolution of barrier island morphology from storms and SLR. Over the course of sea level rising by 1 m, the natural barrier islands are likely to migrate landward in position, with dunes generally decreasing in height relative to sea level and overwashing more frequently, leading to maintenance of interior island elevation relative to sea level as landward migration occurs. These potential increases in interior island elevation with SLR might prevent future flooding of some island interior areas. But because the model results for the 0 m SLR case show that a 20- or 100-year return period storm occurring today would flood over 85% of the land during the storm, it is likely that with 1 m of SLR and the accompanying unknown morphological changes, the flood area during these storms could be at least as great.

Compared to the more extreme storm return periods, the no-storm and 1-year return period storm model results have a broader range of flood areas across SLRs. For example, for 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 m of SLR with no storms, 25%, 47%, 73%, and 84% of the land area would be inundated, respectively. During 1-year storm events, flooded areas increase, with a smaller spread between SLR cases than the no-storm condition, to 51%, 64%, 74%, 85%, and 92% of the land flooded for 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 m of SLR, respectively. Again, with the unknown morphological changes that will increasingly occur over time as the barrier islands are allowed to naturally evolve, the flood areas and locations may be different. Thus, these results show us estimates over the present-day subaerial barrier island area and give a qualitative indication of variation between storm intensities and SLRs. Because of the relatively small range in total flood area between all modeled SLRs for 20- and 100-year storm return periods (Fig. 2), these results indicate that even with morphological changes to the islands over time, the 20- and 100-year storms will have a large flood impact. However, the larger ranges in total flood area between SLRs for the no storm and 1-year return period storm cases (Fig. 2) indicate the possibility for higher variability in actual inundated/flooded areas as the island morphology evolves.

Maps of the modeled inundation/flood extent on present-day island morphology for SLRs 0 through 1.5 m (Fig. 3, panels A-E), for the no-storm condition (blue) and where additional flooding would occur due to the 1-year (maroon) and 20-year return period storms (magenta), indicate that inundation/flooding of the interior parts of the islands does not occur without a storm for SLR less than 1 m (panels A-C), but with SLR of 1 m or more, many interior island areas are inundated (panels D and E, blue areas), including Portsmouth Village at the northern end of North Core Banks (Fig. 1B). Changes in morphology may alter future inundation patterns, potentially resulting in less future interior inundation than reported in Fig. 3, due to overwash increasing interior elevations relative to present-day topography. However, the overwash flow and deposition that increase the interior elevation can cause damage to developed barrier island interior areas like the historic Portsmouth Village, which experienced significant damage from flooding during Hurricane Dorian (2019)42. The eastern end of Harkers Island, the ___location of the Park Headquarters and Visitor Center (Fig. 1B), maintains a mainly dry interior for model scenarios of no-storm conditions with up to 1 m of SLR, and flooding over interior areas is limited to storm conditions. Beginning with the 1.5 m SLR model scenario, some interior areas of this part of Harkers Island are projected to experience inundation (Fig. 3E), and total inundation here occurs when SLR > = 3 m (not shown). Because developed Harkers Island is not a barrier island, natural morphology changes like migration would not be occurring here, so it is likely that without further intervention, this area would experience these projected impacts.

Maps of modeled flood plus pond areas over present-day island morphology, for no storm (RP000, blue), 1-year return period (RP001, maroon), and 20-year (RP020, magenta) return period storms, for no SLR (A); 0.25 m SLR (B); 0.5 m SLR (C); 1 m SLR (D); and 1.5 m SLR (E). Layers are additive, in that both blue and maroon together show the inundation for the 1-year return period storm; blue, maroon, and magenta together show inundation for the 20-year return period storm. We created the maps using ESRI ArcMap 10.8.1 software http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

Groundwater depths

As sea level rises, saltwater tends to intrude into the subsurface, pushing the groundwater table upward, which can lead to surface flooding with emergent groundwater and the loss of fresh groundwater, which is a vital resource to plants and animals. Model results estimate the response of the water table depth to SLR, without identifying the salinity, which may be fresh, brackish, or saline. Model results project that much of the land area of CLNS has a shallow depth to groundwater under present conditions (Figs. 4 and 5). Modeled depths of the local, spatially variable groundwater table have been binned into areas with the groundwater table deeper than 2 m (non-hazard) and shallower than 2 m (denoted as groundwater hazard due to the risks from emergent groundwater flooding the land and the loss of fresh groundwater for plants and animals)43, with an additional bin for surface inundation due to marine/tidal influences (Fig. 4). Groundwater table depths were modeled over an approximately 170 km2 area of land and water combined, almost the entire CLNS boundary (see color areas in Fig. 5).

Maps of modeled groundwater depth groups for no SLR (A); 0.25 m SLR (B); 0.5 m SLR (C); 1 m SLR (D); and 1.5 m SLR (E) (no storms). We created the maps using ESRI ArcMap 10.8.1 software http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

For each SLR scenario without storm effects, the model results show more areas with a shallow depth to groundwater (0–2 m, Fig. 4B) than with a deep one (Fig. 4A), by an order of magnitude. As sea level rises, the groundwater table is pushed upward to shallower depths, decreasing the already small areas of deeper groundwater (Fig. 4A). Marine/tidal surface flooding inundates areas with seawater as quickly as SLR pushes groundwater upward, resulting in the decrease of shallow groundwater areas with increasing SLR (Fig. 4B, C and Fig. 5), rather than an increase from emerging groundwater. The National Park Service Supervisory Biologist of CLNS, J. Altman reports they do not see groundwater emerging at the surface, consistent with the model results that indicate marine inundation would occur at the same time, preventing visible emerging groundwater (personal communication, April 30, 2024). The areas and locations of future shallow groundwater may differ from those in Figs. 4 and 5, potentially with some groundwater depths maintained if interior elevations increase with SLR and storms.

Shoreline change

The modeled barrier shoreline of CLNS is projected to generally retreat over time with increasing SLR (Fig. 6), with average erosion values along the full region of 56 m, 92 m, 178 m, 238 m, 298 m, and 418 m for SLRs 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 3 m, respectively. However, there is significant spatial variability due to local erosion/accretion hotspots. For example, the modeled shoreline for 0 m SLR (Fig. 6, dark blue line) has accreted slightly in several locations compared to the initial reference shoreline ___location from the year 1990, when the model is initialized. Local accretion relative to the year 1990 occurs in a few locations in CLNS, primarily along dynamic spits and capes: e.g., for all modeled SLR scenarios at the northern extent around transect 25,000, near Portsmouth Village; and for all but 2 and 3 m SLR at Cape Lookout around transect 23,700. In these two regions, modeled shoreline retreat and accretion do not always occur in rank order of SLR (Figs. 6, 7A and 7E), due to strong local accretion trends in the area, most often due to gradients in longshore transport. For example, around transect 25,000, the modeled shoreline for 0 m SLR accretes less than all SLR cases but 3 m (driven by the persistence of accretionary trends over time), and shorelines for 0.25 and 0.5 m SLR accrete less than some higher SLRs, while just south of that accretion area, the 0 m SLR shoreline retreats more than for SLRs up to 1.5 m. Around Cape Lookout, the shoreline for 0 m SLR retreats more than for up to 1 m SLR and even retreats while they accrete. In all other areas, the retreat is greater for higher SLRs (Figs. 6, 7B–D,F).

Modeled shoreline change projections for each SLR. Panel (A) shows present-day modeled land and water areas, with the same transect numbers indicated as in the y-axis of panel (B). Panel (B) shows shoreline change (m) relative to an initial reference shoreline ___location from the year 1990 (represented by the vertical dashed line along 0 m, which would demonstrate no change). (0 m SLR shows change because it is relative to that reference ___location from 1990.) (In the shoreline change model, SLR values were modeled in time, with the levels relating to the following years: 0 m = 2005; 0.25 m = 2038; 0.5 m = 2062; and 1 m and above = 2100.) We created the map using ESRI ArcMap 10.8.1 software http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

Modeled shoreline change projections overlayed onto maps of some key areas of Cape Lookout National Seashore. Note that the reference shoreline position from 1990 is not shown. Panel (A) shows the shoreline near the historic Portsmouth Village, at the northern extent of the islands, including a ferry terminal. Panels (B) and (C) show camp areas Long Point and Great Island, respectively, each including a ferry terminal. Panel (D) shows the barrier island that is oceanward of Harkers Island, the Park Headquarters ___location. Panel (E) shows Cape Lookout, which includes a ferry terminal, the Cape Lookout Lighthouse, just north of transect 23,800, and a historic U.S. Coast Guard Station. Panel (F) shows the western end of Shackleford Banks, including a ferry terminal. We created the maps using ESRI ArcMap 10.8.1 software http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

In some areas of CLNS, shoreline retreat distances for the higher SLRs approach and often exceed the current island width (e.g., Fig. 7B–F), implying long-term barrier island rollover and recession landward, or the possibility of island breaching in areas with highly variable erosion rates. As sea level rises, the projected new shoreline locations show us the oceanward edge of the islands’ new locations. This landward barrier island migration indicates the flooding and groundwater results, especially for the higher SLRs with more migration, will occur in different locations than shown.

Vertical land motion

Satellite-derived vertical land motion (VLM) for the years 2007 to 2020 at CLNS is universally negative, with subsidence rates increasing in magnitude to the south (Fig. 8). Subsidence rates have been binned into < 2 mm/yr; 2 to 3 mm/yr; and > 3 mm/yr, the most extreme subsidence for the region. Across CLNS, 34% of the subaerial land is subsiding by more than 2 mm/yr, including the eastern end of Harkers Island, where the Park Headquarters is located. The southernmost part of the region is subsiding by as much as 4.0 mm/yr. The other 66% of the region is subsiding at rates between 1.5 and 2.0 mm/yr. This sinking of the land increases relative SLR, which can affect estimated timing of SLR scenarios and their impacts.

Map of satellite derived binned vertical land motion rate in mm/yr, indicating subsidence along all of Cape Lookout National Seashore. We created the map using ESRI ArcMap 10.8.1 software http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

Discussion

For the present-day subaerial islands, focusing on the 0.5 m and 1.5 m SLR scenarios, those closest to the local estimated SLRs for the intermediate-high scenario for the years 2050 (0.46 m) and 2100 (1.60 m)14, respectively, the flooding model projects that close to half of the current land of CLNS will be inundated by 2050 and 84% by 2100. By 2050, annual storms could flood an additional 27% of land, for a total of 74% of the current land covered in water; and by 2100, 92% would be covered in water during an annual storm. Sound-side flooding of CLNS (Fig. 3) is a significant hazard, and it could drive further geomorphic changes not addressed in these studies34. The main concern with groundwater depths here is the projected loss of groundwater with SLR, including the loss of deep (> 2 m) groundwater areas, which are projected to decline from ~ 6 km2 presently to ~ 3 km2 in 2050 and ~ 1 km2 in 2100. Flooding from emergent groundwater here is not projected to be an extensive hazard in itself because marine/tidal inundation is projected to overtake most areas on CLNS where shallow groundwater would emerge. Average model estimates for shoreline retreat for the years 2050 and 2100 suggest that in narrower island regions, the retreat could be around 20–30% and 50–80% of the island width, respectively. The land subsidence of CLNS could accelerate the timing of each of these hazards. For example, a subsidence rate of 4 mm/yr in 100 years would raise relative sea level by 0.4 m, and therefore hazard exposure projections expected by 2100 could occur several decades earlier.

The projected shoreline positions and unmodeled changes in barrier island locations and morphology may increasingly change the patterns and total areas of flooding and groundwater depth categories with SLR. There have been successful attempts on modeling combined morphologic change and storm flooding on barrier islands44, but they were over short time scales. Modeling long-term morphologic change remains hindered by lack of long-term site-specific data and computational efficiency17.

The shoreline-change projections presented here do not explicitly parameterize processes related to long-term barrier-island migration, e.g., overwash, breaching, and inlet sediment dynamics, but instead captures these processes implicitly via the assumption of equilibrium-profile migration. As modeling advances are made, including changes in barrier island position and morphology in these projections will greatly improve estimates. A few very recent studies21,22 are getting closer to bridging the gap between idealized/exploratory and spatially-explicit/predictive models for barrier system dynamics. Future versions of CoSMoS-COAST are working toward explicitly including coupled beach-dune dynamics.

Modeling advances could also improve the groundwater modeling. The shallow groundwater levels calculated here used a simple representation of the geology and hydrology (see43 for details on model limitations), so a more detailed study incorporating additional hydrologic complexity, including salinity, could provide further understanding of fresh groundwater availability and the response of the water table. For example, increases in annual precipitation, from more severe storms, and from hurricanes45 are likely to lead to more groundwater recharge that is not included in the current models, and additional complexities associated with evapotranspiration, geologic heterogeneity, and salinization processes could diminish freshwater resources.

CLNS, while a largely undeveloped, natural system of barrier islands, still has many ecological, cultural, and historical resources to manage as the islands evolve. As the natural processes of barrier island migration are allowed to occur on CLNS, this will act to help preserve the barrier islands as well as some of the numerous ecological features there, including nesting areas and habitat for federally protected and/or threatened species such as piping plovers, American oystercatchers, and sea turtles, as well as the wild horses on Shackleford Banks. Preserving the barrier islands also means they will continue to be the first line of defense to the mainland coast against flooding and erosion. Although the barrier islands can naturally migrate landward due to SLR, the cultural and historic resources they contain cannot. There are culturally valuable features such as the historical Portsmouth Village at the north end of North Core Banks and the historical Cape Lookout Village. The Cape Lookout Lighthouse, while also a historic feature, is still an operational aid to navigation. There are two areas for cabin camping on the islands—Great Island cabins on South Core Banks and Long Point cabins on North Core Banks—and primitive tent camping is available along the beaches of the islands. There are several ferry landings to access these features.

Even at present-day sea level, storms are already severely impacting the islands of CLNS and its many resources34 (Fig. 2, dark blue boxes; Fig. 3A). In fact, the Long Point Cabins of CLNS were so severely damaged from Hurricane Dorian (2019) that the NPS has determined they cannot sustain the cabins at their current ___location and thus they plan to demolish the damaged structures34,42,46,47. The model results estimate that by 2100, the shoreline near the Long Point cabins may have retreated landward by over half the island width, to around the present-day ferry landing ___location on the sound side of the island (Fig. 7B). This would suggest significant morphological change and migration of the island landward, with the island potentially no longer present in the area of the damaged Long Point cabin infrastructure. Shackleford Banks appears to remain the most stable of the barrier islands across flooding, groundwater, and shoreline change hazards (Figs. 3, 5, 7F), however the increased rate of subsidence here could increase hazard exposure. The horses on Shackleford Banks rely on access to fresh drinking water from freshwater ponds and groundwater that they reach by digging46, so the aforementioned future model improvements would help provide further understanding of the fresh groundwater availability to the horses.

A challenge for the National Park Service is balancing its mission to protect cultural and historic structures and sites while allowing natural processes such as barrier island retreat and overwash to occur. For example, piping plovers have shown a preference for overwash habitats48, but overwash can threaten cultural and historic structures. Managing a diverse array of resources is a common challenge for the agencies tasked with managing barrier islands across the world, and just as on CLNS, requires a wide range of expertise, tools, and decisions to be made to balance the various hazard impacts and budgetary constraints of the agency. The challenge to implement sustainable coastal management practices in a dynamic coastal environment will become exacerbated due to accelerating SLR and storm impacts, and decisions about repairing damage to ecosystems and infrastructure would benefit by considering the combined increased future hazard risks from SLR and storms. Coastal land managers globally will increasingly grapple with the difficult decision to protect vs. relocate coastal resources in the coming decades.

Materials and methods

Overland flooding

Overland flood hazards were simulated with the open-source Super-Fast INundation of CoastS (SFINCS) model49. SFINCS is a computationally efficient reduced complexity model that approximates the shallow water equations, but at a lower computational expense than a traditional full-physics model50. For CLNS, the study area was modeled using one ~ 300 km × 200 km model ___domain from Norfolk to Wilmington in the north–south direction and from the approximate + 10 m NAVD88 landward elevation contour to the -5 m NAVD88 isobath. Remaining sections of the South Atlantic Coast were simulated with four additional overlapping model domains that were merged to create continuous outputs38. The model was run with a grid resolution of 200 m by 200 m in combination with subgrid lookup tables developed from a 1 m resolution topo-bathymetric dataset (Coastal National Elevation Database, CoNED)51,52. Dune heights in the baseline model grid were set to maximum elevations found in the CoNED data within a grid cell containing dunes and cross-checked with Doran et al.53.

Spatiotemporally varying time-series of water levels, wave setup, fluvial discharges, and rainfall were applied at the boundaries of the SFINCS model for tens of thousands of emulated extratropical and tropical storms. In contrast to previous CoSMoS work27, no design event based on offshore conditions is used but flooding for extratropical and tropical simulations were combined on grid cell basis and thus provide a more accurate description of the flood hazards, as hazard and return period are assessed locally at each grid cell. Open boundary water levels (astronomic tides, storm surge, and wave setup) associated with tropical cyclones (TCs) (hurricanes) were derived from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Coastal Hazards System (CHS)54,55,56,57 database of TCs. For extratropical events, the Global Tide and Surge Model (GTSM)58,59,60 outputs and externally computed wave setup were used39.

The CHS is a hybrid probabilistic-dynamic model using the joint probability method and statistically/dynamically downscaled storm surge, tides, waves, and wave setup. Wave setup for all non-hurricane events were computed with the empirical Stockdon61 formulation using local foreshore beach slopes62 and WaveWatch3 (WW3) simulated waves63. The GTSM and WW3 models were forced by three global climate models (GCMs) from the High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP, 6th generation Coupled Model Intercomparison Project – CMIP6) that represent the ‘high’ emissions scenario SSP5-8.5 for the projection period (2020–2050). The HighResMiP models CMCC-CM2-VHR464, GFDL-CMC4C19265, and HadGEM366 were chosen because of the finer atmosphere and ocean grid resolutions (25–50 km) which better resolve coastal storm events compared to previous GCMs (O(100kms))67,68 and have a similar resolution to the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis-5 (ERA5)69. Rainfall was obtained directly from GCM outputs and for the TC runs were based on the Interagency Performance Evaluation Task Force Rainfall Analysis70 method.

Further information on model setup and validation is detailed in Nederhoff38. The physics-based hydrodynamic modeling used for the flood assessment can skillfully reproduce coastal water levels based on a comprehensive validation of tides, almost two hundred historical storms, and an in-depth hindcast of Hurricane Florence38. The validations nearest our study region have a mean-absolute-error (MAE) of 8.3 cm for tide and 14.7 cm for storms at the Oregon Inlet Marina, NC, and an MAE of 6.5 cm for tide and 9.7 cm for storms at Beaufort, NC38.

Groundwater depths

Groundwater levels were simulated using steady-state MODFLOW-NWT71 groundwater flow models after the methodology used in CoSMoS applied to California43. The response of the water table depth to SLR was modeled without identifying the salinity of the groundwater. For the CLNS, only one groundwater model ___domain spanned the full study area, whereas other regions of the full U.S. Southeast model ___domain included overlapping models that were merged to create continuous outputs. The groundwater model was developed using a 50 m by 50 m square grid cell size in the horizontal and a variable thickness set by a previous groundwater flow model in the area72, based on calibrated geologic structure which used an inverse process to adjust the aquifer thickness and hydraulic conductivity of the shallow aquifer to match observed well levels as closely as possible. The hydraulic conductivity in each grid cell was assigned by dividing the calibrated transmissivity by the saturated thickness modeled by Zell and Sanford72. The top model surface, the ground surface, was set to the topography, down-sampled from the 1-m elevation model used for the overland flood hazards51,52. This surface of the model had of two boundary conditions: 1) recharge prescribed by average annual recharge derived from 2000–2013 observations and empirical regression equations73,74 (RCH MODFLOW package), and 2) a drain condition with an elevation set to the topographic elevation of the grid cell and a conductance set by the grid cell size and the cell hydraulic conductivity (DRN MODFLOW package).

Full CoSMoS water level outputs were not available at the time of the groundwater modeling, so the marine boundary condition, set as a constant head cell (CHD MODFLOW package), was assigned the nearest elevation from the gridded NOAA VDATUM Mean Higher High Water dataset75 for present day and raised by a constant amount of SLR for higher sea level scenarios in separate model instances. Future research should directly include dynamic marine boundary conditions from CoSMoS flood modeling into the groundwater modeling, which would help determine the full transient nature of the groundwater hazard, such as during storms. This improvement would come at a significant cost in increased modeling complexity and has not yet been implemented. Water table depth was calculated at a 10 m by 10 m resolution using the modeled hydraulic heads subtracted from the DEM.

Shoreline Change

Shoreline change was modeled with CoSMoS-COAST76,77,78, which solves the one-dimensional conservation of sediment volume in the alongshore direction that is given by:

As discussed in Vitousek et al.78, Eq. (1) synthesizes several popular individual-process models including: {1} a ‘one-line’ model for longshore transport; {2} a cross-shore beach profile change model due to sea-level rise; {3} a long-term residual shoreline trend that represents sources and sinks of sediment, {4} a wave-driven cross-shore equilibrium shoreline change model, and finally {5} a noise term.

The South Atlantic model is comprised of roughly 34,000 transects (spaced every 50 m in the alongshore direction), which span open-coast sandy beaches on the U.S. South Atlantic Coast from Miami, Florida, to Cape Henlopen, Delaware. The portion of the model covering CLNS is comprised of 1,593 transects. The model was forced with daily hindcasted and projected wave conditions obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis and 7 future wave scenarios from the CMIP6 collection of GCMs, respectively, thus including stochasticity of storm dynamics. The model was calibrated via an ensemble Kalman filter using a 200-member model ensemble and 25 years of satellite-derived shorelines observations (from 1990–2015 and spanning the entire model ___domain) obtained using the CoastSat toolbox79, thus implicitly accounting for the effects of local dune dynamics on shoreline position. After the calibration period, the model was validated using 5 years of satellite-derived shoreline observations (from 2015–2020). The validation period assesses that the model achieves a median root-mean-square accuracy of 11.5 m across CLNS and 12.3 m across the entire South Atlantic ___domain, respectively.

The model currently only keeps track of one coastal feature (i.e., the Mean Sea Level shoreline contour; variable Y in Eq. (1)), and assumes that other morphologic features, e.g., dune toe and crest positions and back barrier shoreline, remain in equilibrium with this reference feature. Other long term coastal morphology models account for the coevolution of many components of barrier island systems (e.g., shoreface, barrier/dune, marsh, and lagoon; see review by Hoagland et al.17), with a small subset of models including all aforementioned barrier-island components32,80,81. But, these long-term barrier-island models, which were originally created to explore morphodynamics, have largely remained exploratory17. The limited availability of spatially and temporally dense observations of coastal features such as dune toe, dune crest, and back barrier shoreline, which are needed to understand and model how these features change over time, is a limiting factor for “predictive” rather than “exploratory” modeling of barrier islands, based on the definitions in Murray82. As datasets of coastal profile elevations, such as Doran et al.53, become more spatiotemporally dense, models can begin to assimilate and integrate these features into predictions.

Recent remote sensing methods79 have provided tremendous resources for historical shoreline positions, which represent the basis for the data-driven future projection modeling of the current application. Many modern barrier island migration models rely on equilibrium profile transgression17,83, which implicitly accounts for processes such as overwash. A limitation to this model, and to most long-term barrier island transgression models, is that it does not consider the effect of breaches, which are possible due to SLR in the future. If temporary breaches fill in over time34, then the model results presented here should be a robust estimate despite this unavoidable uncertainty. More information on the model and validation is detailed in40.

Vertical land motion

We employed an advanced multitemporal synthetic aperture radar (SAR) processing algorithm to determine VLM using data obtained from the ascending orbit of Sentinel-1 A/B and ALOS-1 satellites. Initial steps involved the creation of line-of-sight (LOS) velocity maps for Sentinel-1 A/B and ALOS-1 satellites using a multitemporal wavelet-based InSAR (WabInSAR) algorithm84,85,86,87. We used GAMMA software88 to generate interferograms. Interferograms were corrected for the effect of topography using the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)89 30 m digital elevation model (DEM). Elite (i.e., less noisy) pixels were obtained by applying a threshold of 0.7 on the temporal averaged coherence of each pixel. To estimate the absolute phase change of elite pixels, we applied a minimum cost flow algorithm90, suitable for sparsely distributed pixels91. Next, we corrected unwrapped interferograms for the effect of orbital error92, topographically correlated atmospheric phase delay, and spatially uncorrelated DEM error77,78. We applied a reweighted least-squares optimization to resolve each pixel’s Line-of-Sight (LOS) time series and velocity85. To generate the 3D velocities tied to the International Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) Service reference global frame of 2014 IGS14, we used a stochastic model93 to combine the LOS velocities with the observation of GNSS. The validation test against independent GNSS measurements yields an accuracy better than 1 mm/yr for the VLM rate within the IGS14 reference frame94. Ohenhen94 has published VLM data from 2007 to 2020, encompassing the study area with continuous spatial coverage at a 50-m resolution.

Data availability

All data used in this publication are available from: Barnard, P.L., Befus, K.M., Danielson, J.J., Engelstad, A.C., Erikson, L.H., Foxgrover, A.C., Hardy, M.W., Hoover, D.J., Leijnse, T., Massey, C., McCall, R., Nadal-Caraballo, N., Nederhoff, K.M., Ohenhen, L., O'Neill, A., Parker, K.A., Shirzaei, M., Su, X., Thomas, J.A., van Ormondt, M., Vitousek, S.F., Vox, K., and Yawn, M.C., 2023, Future coastal hazards along the U.S. North and South Carolina coasts: U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5066/P9W91314. Each of the datasets shown in this publication were downloaded from the above source, and then reduced to just present the CLNS region (Fig. 1) for the following specific products: projections of coastal flood hazards and flood potential; projected groundwater emergence and shoaling; projections of shoreline change of current and future (2005–2100) sea-level rise scenarios (case 4, shoreline positions are allowed to move landward without limitation, and the model assumes recent historical accretion rates continue into the future; slope B, intermediate slope); and vertical land motion rates for the years 2007 to 2020. The boundary for Cape Lookout National Seashore came from the National Park Service nps boundary ArcGIS open dataset at https://public-nps.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/nps::nps-boundary-1/explore.

Change history

19 January 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: Reference 40 has been updated.

References

Hinkel, J. et al. A global analysis of erosion of sandy beaches and sea-level rise: An application of DIVA. Glob. Planetary Changehttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.09.002 (2013).

Rotzoll, K. & Fletcher, C. H. Assessment of groundwater inundation as a consequence of sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Changehttps://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1725 (2013).

Vitousek, S. et al. Doubling of coastal flooding frequency within decades due to sea-level rise. Sci. Rep.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01362-7 (2017).

Oost, A. P. et al. Barrier island management: Lessons from the past and directions for the future. Ocean Coast. Manag. 68, 18–38 (2012).

Beckley, B. et al. Global Mean Sea Level Trend from Integrated Multi-Mission Ocean Altimeters TOPEX/Poseidon, Jason-1, OSTM/Jason-2, and Jason-3 Version 5.1. NASA Physical Oceanography DAAC. 10.5067/GMSLM-TJ151 (2021).

Guérou, A. et al. Current observed global mean sea level rise and acceleration estimated from satellite altimetry and the associated measurement uncertainty. Ocean Sci. 19(2), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-330 (2023).

Hay, C. C., Morrow, E., Kopp, R. E. & Mitrovica, J. X. Probabilistic reanalysis of twentieth-century sea-level rise. Nature 517(7535), 481–484. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14093 (2015).

Sallenger, A. H., Doran, K. S. & Howd, P. A. Hotspot of accelerated sea-level rise on the Atlantic coast of North America. Nat. Clim. Changehttps://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1597 (2012).

Ezer, T., Atkinson, L. P., Corlett, W. B. & Blanco, J. L. Gulf Stream’s induced sea level rise and variability along the U.S. mid-Atlantic coast. J. Geophys. Res. Oceanhttps://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20091 (2013).

Valle-Levinson, A., Dutton, A. & Martin, B. Spatial and temporal variability of sea level rise hot spots over the eastern United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7876–7882. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL07392 (2017).

Yin, J., & Goddard, P. B. Oceanic control of sea level rise patterns along the East Coast of the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5514–5520; https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL057992 (2013).

Domingues, R., Goni, G., Baringer, M. & Volkov, D. What Caused the Accelerated Sea Level Changes Along the U.S. East Coast During 2010–2015?. Geophys. Res. Lett.https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL081183 (2018).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Sea Level Trends. https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=8656483#tab50yr (2023).

Sweet, W.V. et al. Global and regional sea level rise scenarios for the United States: updated mean projections and extreme water level probabilities along U.S. coastlines. NOAA Technical Report NOS 01. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service, Silver Spring, MD, 111 pp., https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/hazards/sealevelrise/noaa-nos-techrpt01-global-regional-SLR-scenarios-US.pdf (2022).

Sweet, W. V., Dusek, G., Obeysekera, J., & Marra, J. J. Patterns and projections of high tide flooding along the U.S. coastline using a common impact threshold. NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 086. Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services. https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/publications/techrpt86_PaP_of_HTFlooding.pdf (2018).

Taherkhani, M. et al. Sea-level rise exponentially increases coastal flood frequency. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 6466 (2020).

Hoagland, S. W. et al. Advances in morphodynamic modeling of coastal barriers: A review. J. Waterway Port Coastal Ocean Eng. 149(5), 03123001 (2023).

Murray, A. B. & Moore, L. J. Geometric constraints on long-term barrier migration: from simple to surprising. In Barrier dynamics and response to changing climate (eds Moore, L. J. & Murray, A. B.) (Springer, 2018).

Davis, R. A. Jr. & Barnard, P. L. Morphodynamics of the barrier-inlet system, west-central Florida. Marine Geol. 200(1–4), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(03)00178-6 (2003).

Stutz, M. & Pilkey, O. The relative influence of humans on barrier islands: Humans versus geomorphology. Rev. Eng. Geol., https://doi.org/10.1130/2005.4016(12) (2005).

Anarde, K. A., Moore, L. J., Murray, A. B., & Reeves, I. R. B. The future of developed barrier systems—Part I: Pathways toward uninhabitability, drowning, and rebound. Earth’s Future 12, e2023EF003672; https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003672 (2024).

Anarde, K. A., Moore, L. J., Murray, A. B., & Reeves, I. R. B. The future of developed barrier systems—Part II: Alongshore complexities and emergent climate change dynamics. Earth’s Future 12, e2023EF004200; https://doi.org/10.1029/2023E (2024).

National Park Service. Coastal Storm Response--Hurricane Isabel. Geologyhttps://www.nps.gov/subjects/geology/coastal-storm-response-hurricane-isabel.htm (2019).

Barnard, P. L. et al. Development of the Coastal Storm Modeling System (CoSMoS) for predicting the impact of storms on high-energy, active-margin coasts. Nat. Hazards 74(2), 1095–1125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1236-y (2014).

Barnard, P. L. et al. Dynamic flood modeling essential to assess the coastal impacts of climate change. Sci. Rep.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40742-z (2019).

Erikson, L. H. et al. Projected 21st century coastal flooding in the Southern California Bight. Part 2: tools for assessing climate change driven coastal hazards and socio-economic impacts. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse6030076 (2018).

O’Neill, A. C. et al. Projected 21st century coastal flooding in the Southern California Bight. Part 1: development of the third generation CoSMoS model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 6, 59 https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse6020059 (2018).

Barnard, P. L. et al., Future coastal hazards along the U.S. North and South Carolina coasts. U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/10.5066/P9W91314 (2023a).

Barnard, P. L. et al., 2023 Future coastal hazards along the U.S. the U.S. Southeast Atlantic coast. US Geological Survey data release: https://doi.org/10.5066/P9BQQTCI (2023).

Walters, D., Moore, L. J., Vinent, O. D., Fagherazzi, S. & Mariotti, G. Interactions between barrier islands and backbarrier marshes affect island system response to sea level rise: Insights from a coupled model. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 119, 2013–2031. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JF003091 (2014).

Durán Vinent, O. & Moore, L. Barrier island bistability induced by biophysical interactions. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2474 (2015).

Reeves, I. R. B., Goldstein, E. B., Anarde, K. A. & Moore, L. J. Remote bed-level change and overwash observation with low-cost ultrasonic distance sensors. Shore & Beachhttps://doi.org/10.34237/1008923 (2021).

Mariotti, G. & Hein, C. J. Lag in response of coastal barrier-island retreat to sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00980-9 (2022).

Sherwood, C. R. et al. Sound-side inundation and seaward erosion of a barrier island during hurricane landfall. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surfacehttps://doi.org/10.1029/2022JF006934 (2023).

Jay, K. R., Hacker, S. D., Hovenga, P. A., Moore, L. J. & Ruggiero, P. Sand supply and dune grass species density affect foredune shape along the US Central Atlantic Coast. Ecospherehttps://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4256 (2022).

Hovenga, P. A. et al. Quantifying the relative influence of coastal foredune growth factors on the US mid-Atlantic Coast using field observations and the process-based numerical model. Windsurf. Coast. Eng.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2022.104 (2023).

Leijnse, T. et al. Rapid modeling of compound flooding across broad coastal regions and the necessity to include rainfall-driven processes: a case study of Hurricane Florence. Coastal Sediments 2023 Conference Proceedingshttps://doi.org/10.1142/9789811275135_0235 (2023).

Nederhoff, K. et al. Tropical or extratropical cyclones: what drives the compound flood hazard, impact, and risk for the United States Southeast Atlantic coast?. Nat. Hazards.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-024-06552-x (2024).

Parker, K. et al. Relative contributions of water-level components along the US Southeast Atlantic Coast from a regional-scale water-level hindcast. Nat. Hazardshttps://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-05939-6 (2023).

Vitousek, S. et al. Scalable, data-assimilated models predict large-scale shoreline response to waves and sea-level rise, Sci. Rep., 14, 28029, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77030-4 (2024).

Flick, R. E., Chadwick, D. B., Briscoe, J. & Harper, K. C. Flooding” versus “inundation. Eos Trans.https://doi.org/10.1029/2012EO380009 (2012).

Dolce, C. Hurricane Dorian damaged historic structures and changed the coastline along parts of North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Weather Ungerground News & Blogshttps://www.wunderground.com/article/storms/hurricane/news/2019-09-10-cape-lookout-national-seashore-new-inlets-hurricane-dorian (2019).

Befus, K. M., Barnard, P. L., Hoover, D. J., Finzi Hart, J. A. & Voss, C. I. Increasing threat of coastal groundwater hazards from sea-level rise in California. Nat. Clim. Changehttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0874-1 (2020).

Sherwood, et al. Modeling the morphodynamics of coastal responses to extreme events: What shape are we in?. Ann. Rev. Marine Sci. 14(1), 457–492. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032221-090215 (2022).

Kunkel, K.E. et al. North Carolina Climate Science Report. North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies, 233 pp. https://ncics.org/nccsr (2020).

National Park Service. Cape Lookout National Seashore, North Carolina. https://www.nps.gov/calo/index.htm (2024).

Sherwood, C.R. Erosion and recovery: Sound-side inundation of Cape Lookout National Seashore during Hurricane Dorian. USGS Publications Warehouse. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/70221844 (2021).

Zeigler, S. L., Gutierrez, B. T., Hecht, A., Plant, N. G. & Sturdivant, E. J. Piping plovers demonstrate regional differences in nesting habitat selection patterns along the US Atlantic coast. Ecosphere 12(3), e03418. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3418 (2021).

Leijnse, T., van Ormondt, M., Nederhoff, K. & van Dongeren, A. Modeling compound flooding in coastal systems using a computationally efficient reduced-physics solver: Including fluvial, pluvial, tidal, wind- and wave-driven processes. Coastal Eng.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2020.103796 (2021).

Nederhoff, K. et al. Dynamic modeling of coastal compound flooding hazards due to tides, extratropical storms, waves, and sea-level rise: a case study in the Salish Sea, Washington (USA). Water 16(2), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16020346 (2024).

Danielson, J. J. et al. Topobathymetric elevation model development using a new methodology: Coastal national elevation database. J. Coastal Res. 76(sp1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI76-008 (2016).

Tyler, D. et al. Topobathymetric Model of the Coastal Carolinas, 1851 to 2020. U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/10.5066/P9MPA8K0 (2022).

Doran, K. S. et al. Lidar-derived beach morphology (dune crest, dune toe, and shoreline) for U.S. sandy coastlines (ver. 4.0, October 2020). U.S. Geological Survey data release. https://doi.org/10.5066/F7GF0S0Z (2017).

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Coastal & Hydraulics Laboratory. Coastal Hazards System, V2.0. https://chs.erdc.dren.mil/ (2023).

Nadal-Caraballo, N. C. et al. Coastal hazards system: A probabilistic coastal hazard analysis framework. J. Coastal Res. 95(sp1), 1211. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI95-235.1 (2020).

Nadal-Caraballo, N. C. et al. Coastal Hazards System–Louisiana (CHS-LA). Coastal and Hydraulics. ERDC/CHL TR 22–16. Vicksburg, MS: US Army Engineer Research and Development Center.https://doi.org/10.21079/11681/45286 (2022).

Massey, T.C. et al. Calibration and Validation of the Coastal Storm Modeling System (CSTORM-MS) Setup for the South Atlantic Domain of the South Atlantic Coastal Study (SACS). Coastal and Hydraulics Lab. ERDC/CHL LR-21–4. Vicksburg, MS: US Army Engineer Research and Development Center (2021).

Muis, S., Verlaan, M., Winsemius, H. C., Aerts, J. C. J. H. & Ward, P. J. A global reanalysis of storm surges and extreme sea levels. Nat. Commun. 7(May), 11969. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11969 (2016).

Muis, S. et al. Global sea level change time series from 1950 to 2050 derived from reanalysis and high resolution CMIP6 climate projections. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.a6d42d60 (2022).

Muis, S. et al. Global projections of storm surges using high-resolution CMIP6 climate models. Earth’s Futurehttps://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003479 (2023).

Stockdon, H. F., Holman, R. A., Howd, P. A. & Sallenger, A. H. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coastal Eng. 53(7), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2005.12.005 (2006).

Doran, K. S., Long, J. W., & Overbeck, J. R. A method for determining average beach slope and beach slope variability for U.S. sandy coastlines. U.S. Geological Survey Open Report. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151053 (2015).

Erikson, L. H. et al. Ocean wave time-series data simulated with a global-scale numerical wave model under the influence of projected CMIP6 wind and sea ice fields. U.S. Geol. Survey Data Releasehttps://doi.org/10.5066/P9KR0RFM (2022).

Scoccimarro, E., Bellucci, A. & Peano, D. CMCC CMCC-CM2-VHR4 model output prepared for CMIP6 HighResMIP. Earth Syst. Grid Feder.https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.1367 (2017).

Guo, H., John, J. G., Blanton, C., & McHugh, C. NOAA-GFDL GFDL-CM4 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp585. Download 20190906. Earth System Grid Federationhttps://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.9268 (2018).

Roberts, M. MOHC HadGEM3-GC31-HM model output prepared for CMIP6 HighResMIP highres-future. Download 20191211. Earth System Grid. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.5984 (2019).

Roberts, M. J. et al. Projected Future Changes in Tropical Cyclones Using the CMIP6 HighResMIP Multimodel Ensemble. Geophys. Res. Lett.https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL088662 (2020).

Dullaart, J. C. M., Muis, S., Bloemendaal, N. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Advancing global storm surge modelling using the new ERA5 climate reanalysis. Clim. Dynam. 54(1–2), 1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-05044-0 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Interagency Performance Evaluation Task Force (IPET). Performance evaluation of the New Orleans and Southeast Louisiana Hurricane Protection System draft final report of the Interagency Performance Evaluation Task Force volume VIII – engineering and operational risk and reliability analysis. (2006).

Niswonger, R.G., Panday, S., & Ibaraki, M. MODFLOW-NWT, a Newton formulation for MODFLOW-2005. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods 6-A37, 32 (2011).

Zell, W. O. & Sanford, W. E. Calibrated Simulation of the Long-Term Average Surficial Groundwater System and Derived Spatial Distributions of its Characteristics for the Contiguous United States. Water Resourc. Res. 56, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026724 (2020).

Reitz, M., Sanford, W. E., Senay, G. B. & Cazenas, J. Annual estimates of recharge, quick-flow runoff, and ET for the contiguous US using empirical regression equations, 2000–2013. US Geol. Survey Data Releasehttps://doi.org/10.5066/F7PN93P0 (2017).

Reitz, M., Sanford, W. E., Senay, G. B. & Cazenas, J. Annual estimates of recharge, quick-flow runoff, and evapotranspiration for the contiguous U. S. using empirical regression equations. Journal of the American Water Resources Association (JAWRA)https://doi.org/10.1111/1752-1688.12546 (2017).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Estimation of vertical uncertainties in VDatum. https://vdatum.noaa.gov/docs/est_uncertainties.html (2018).

Vitousek, S., Barnard, P. L., Limber, P., Erikson, L. H. & Cole, B. A model integrating longshore and cross-shore processes for predicting long-term shoreline response to climate change. J. Geophys. Res.https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JF004065 (2017).

Vitousek, S. et al. The application of ensemble wave forcing to quantify uncertainty of shoreline change models. J. Geophys. Res.https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JF005506 (2021).

Vitousek, S. et al. A model integrating satellite-derived shoreline observations for predicting fine-resolution shoreline response to waves and sea-level rise applied across vast geographic scales. J. Geophys. Res.https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JF006936 (2023).

Vos, K., Splinter, K. D., Harley, M. D., Simmons, J. A. & Turner, I. L. CoastSat: A Google Earth Engine-enabled Python toolkit to extract shorelines from publicly available satellite imagery. Environ. Model. Softw. 122, 104528 (2019).

Lorenzo-Trueba, J. & Mariotti, G. Chasing boundaries and cascade effects in a coupled barrier-marsh-lagoon system. Geomorphologyhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.04.019 (2017).

Palalane, J. & Larson, M. A long-term coastal evolution model with longshore and cross-shore transport. J. Coastal Res. 36(2), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-17-00020.1 (2020).

Murray, A. B. Reducing model complexity for explanation and prediction. Geomorphologyhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.10.020 (2007).

Davidson-Arnott, R. G. & Bauer, B. O. Controls on the geomorphic response of beach- dune systems to water level rise. J. Great Lakes Res.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2021.05.006 (2021).

Lee, J. C. & Shirzaei, M. Novel algorithms for pair and pixel selection and atmospheric error correction in multitemporal InSAR. Remote Sens. Environ.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2022.113447 (2023).

Shirzaei, M. A wavelet-based multitemporal DInSAR algorithm for monitoring ground surface motion. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 10(3), 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2012.2208935 (2012).

Shirzaei, M. & Bürgmann, R. Topography correlated atmospheric delay correction in radar interferometry using wavelet transforms. Geophys. Res. Lett.https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049971 (2012).

Shirzaei, M., Manga, M. & Zhai, G. Hydraulic properties of injection formations constrained by surface deformation. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2019.03.025 (2019).

Werner, C., Wegmüller, U., Strozzi, T., & Wiesmann, A. Gamma SAR and interferometric processing software. Paper presented at Proc. Ers-envisat symposium, Gothenburg, Sweden, Citeseer. (2000).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys.https://doi.org/10.1029/2005rg000183 (2007).

Costantini, M. A novel phase unwrapping method based on network programming. Geosci. Remote Sens. IEEE Trans. 36(3), 813–821 (1998).

Costantini, M., & Rosen, P. A. A generalized phase unwrapping approach for sparse data. Paper presented at Proceedings of the IEEE 1999 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Hmburg (1999).

Shirzaei, M. & Walter, T. R. Estimating the effect of satellite orbital error using wavelet-based robust regression applied to InSAR deformation data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 49(11), 4600–4605. https://doi.org/10.1109/Tgrs.2011.2143419 (2011).

Blackwell, E., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C. & Werth, S. Tracking California’s sinking coast from space: Implications for relative sea-level rise. Sci. Adv.https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba4551 (2020).

Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M. & Barnard, P. L. Slowly but surely: exposure of communities and infrastructure to subsidence on the US east coast. PNAS Nexushttps://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad426 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the internal and external (anonymous and Laura J. Moore) reviewers for their constructive feedback for improving this paper. We appreciate the National Park Service staff members, Jon Altman, Supervisory Biologist for Cape Lookout National Seashore, and Jeffrey West, Superintendent for Cape Lookout National Seashore, for reading and commenting on this paper and providing empirical insight on hazards at Cape Lookout National Seashore. We appreciate the assistance of Ian Reeves, USGS, for additional internal review support. Support for this research project was provided by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Coastal and Marine Hazards and Resources Program, the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Act of 2019 (H.R. 2157), and the National Park Service. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each named author contributed to the writing and editing of this paper and to the generation of at least one of the data sets presented. J. A. Thomas, P. L. Barnard, L. H. Erikson, K. Parker, and K. Nederhoff all contributed to the generation of the flood modeling data set; K. Befus contributed to the groundwater modeling data set; S. Vitousek contributed to the shoreline change data set; and M. Shirzaei contributed to the vertical land motion data set.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, J.A., Barnard, P.L., Vitousek, S. et al. The projected exposure and response of a natural barrier island system to climate-driven coastal hazards. Sci Rep 14, 25814 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76749-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76749-4