Abstract

The development of thermoelectric devices provides an ideal solution for self-sustaining Internet of Things (IoT) applications. However, existing thermoelectric devices face issues such as low integration levels and poor stability. To address these challenges, this paper presents a novel method for fabricating flexible thermoelectric devices using Ag2Se/MgAgSb, which combines MEMS lithographic lift-off techniques to achieve precise control over the dimensions of the thermoelectric functional layer while also reducing fabrication costs. The optimal cell dimensions were identified through simulations. The device achieved an open circuit voltage of 0.49 mV at a temperature difference of 50 K. Additionally, the output power density of the Ag₂Se/MgAgSb flexible Y-type thermoelectric device reached 3.39 µW/m² at a temperature difference of 5 K. The device also demonstrated excellent flexibility; even after being bent 800 times around a glass rod with a diameter of 4 mm, its conductivity decreased by only 12%. Furthermore, it maintained stability under high humidity conditions. This work offers a novel strategy for the miniaturization and large-area controllable fabrication of flexible and reliable thermoelectric devices, as well as an enhancement in their reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rise and development of the Internet of Things (IoT), traditional battery power supply technologies are insufficient to ensure stable long-term operation of smart devices, necessitating urgent exploration of new energy supply methods1,2. Thermoelectric devices present a promising solution, as they can directly convert temperature differences into electrical potential without the need for specific conditions like solar panels or triboelectric nanogenerators. This capability positions thermoelectric technology as an ideal candidate for self-powered applications3,4.

The integration of IoT devices demands the miniaturization of energy supply methods. By leveraging MEMS technology, it is possible to achieve significant reductions in device size5,6. The structure of thermoelectric devices plays a critical role in determining their output performance. Generally, thermoelectric devices can be categorized into vertical (π-type)2,7,8, planar9,10 and annular11,12 structures based on the arrangement of thermoelectric materials and electrodes. However, these conventional structures often require thick layers of thermoelectric material, which limits their compatibility with micro-devices. And at the micro-scale, contact resistance can greatly affect the performance and overall reliability of flexible thermoelectric devices. This phenomenon is intrinsically linked to a variety of factors such as material properties, surface morphology, contact situation and environmental conditions. Y-type devices have been explored to address this challenge, offering enhanced temperature acquisition capabilities13.

Despite advancements, methods such as chemical vapor deposition for fabricating thermoelectric functional layers typically result in low density, slow deposition rates, and high costs14,15. In contrast, films produced by magnetron sputtering exhibit high quality, uniformity, rapid deposition rates, and scalability for large-area applications16,17. In addition, in order to pattern the functional layer, etching technology is often used in the existing research18,19. Existing research often employs etching technology for patterning functional layers; however, despite developments in ion etching20,21, laser etching22,23 and other processes24,25, etching processes tend to be slow and lack precision, making large-area fabrication problematic. Lift-off technology, which utilizes photoresist to remove excess materials, presents a cost-effective and straightforward alternative to etching, yet its application in thermoelectric devices remains underexplored26,27. Therefore, there is a pressing need to investigate efficient fabrication techniques for Y-type devices using magnetron sputtering and lift-off methods.

In this paper, a fabrication method of Y-type flexible thermoelectric device based on MEMS controllable peeling technology is proposed. The thermoelectric functional layer is the Ag2Se/MgAgSb material studied by our group in the early stage28. The materials have good thermoelectric properties and shows certain potential in the application of the Internet of things. The Y-type flexible thermoelectric device was successfully fabricated and systematically tested. The magnetron sputtering process was employed for preparing the thermoelectric functional layer, with its patterning achieved via peeling technology. This process is characterized by simplicity, low cost, and the ability for large-area fabrication. The designed Y-type thermoelectric device enhances the efficiency of thermoelectric temperature difference collection and can be customized according to specific requirements. The preparation method proposed herein offers an ideal solution for the miniaturization and large-area application of flexible thermoelectric devices.

Experiment

Materials

PDMS was sourced from Suzhou Ruicai Semiconductor Co., while 3-inch single silicon wafers were obtained from Suzhou Research Materials Micro-Nano Technology Co., Ltd. Photosensitive polyimide photoresist (PI JAPB-101), RDP-2100P photoresist, Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH), and acetone were procured from Nantong Jingai Microelectronics Technology Co., Ltd. Ag2Se and MgAgSb targets were purchased from Beijing Zhongnuo New Material Technology Co., Ltd. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was acquired from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co.

Design and optimize

The equivalent circuit of FTEG as a power supply with load resistance is shown in the Fig. 1. The matching of the internal resistance of the device and the load resistance is particularly important.

The load voltage of the device(VL) can be expressed as :

Where V0 is the open circuit voltage of the device, Rteg is the internal resistance of the device, RL is the load resistance of the device, Sn is the Seebeck coefficient of n-type materials, and Sp is the Seebeck coefficient of p-type materials. The output power of the device(PL) can be expressed as :

Where IL is the load current. When the internal resistance of the device is the same as the load resistance, the output power of the device is the largest, and the maximum output power(Pmax) can be expressed as :

The internal resistance of the device is affected by the resistance of the thermoelectric unit. The resistance of the thermoelectric unit is related to its size and can be expressed as

Where l is the length of the thermoelectric unit, S is the surface area of the thermoelectric device, ρn is the resistivity of the n-type materials, and ρp is the resistivity of the p-type materials. Therefore, the maximum output power of the device can be expressed as

Where n is the number of n/p thermoelectric unit groups. It can be seen from this formula that the output power of the device is affected by the length and width of the thermoelectric unit. Therefore, the Comsol software is used to simulate the length and width of the thermoelectric unit. The Fig. 2 shows the heat transfer simulation results of FTEG.

In a fixed space, increasing the size of the thermoelectric unit leads to an enhancement in the output power of the device. However, a simultaneous increase in both length and width results in higher resistance within the thermoelectric unit, which can decrease the overall integration of the device. Therefore, it is essential to consider the output power per unit weight of the device to determine its optimal dimensions. In the Fig. 3, analysis of the data reveals that when the length of the thermoelectric unit is set to 800 μm, the output power per unit weight reaches its maximum. Similarly, a width of 600 μm also yields the highest output power per unit weight. Consequently, the designed dimensions for the thermoelectric unit are 800 μm in length and 600 μm in width.The optimized design maximizes the output power per unit weight of the device, highlighting the importance of balancing size with resistance to achieve efficient energy conversion in the FTEG system.

FTEG fabrication

The overall flow chart of flexible thermoelectric devices prepared using the MEMS process is illustrated in Fig. 4. The fabrication process begins with the preparation of a 3-inch single-sided silicon wafer, followed by organic cleaning. Next, 300 nm of aluminum (Al) is sputtered onto the silicon wafer, serving as a metal sacrificial layer that can react with dilute hydrochloric acid.

Subsequently, photosensitive polyimide photoresist is spin-coated onto the Al sacrificial layer. The coating process involves low-speed rotation at 500 rpm for 10 s, followed by high-speed rotation at 3000 rpm for 45 s, achieving a film thickness of 6 μm. The coated wafer is then exposed under a UV lithography machine with an exposure dose of 200 mJ. TMAH (2.38%) developer is used to develop the pattern, resulting in the formation of the side electrode pattern.

The next step involves polyimide imidization, starting at a low temperature of 140 °C and gradually increasing to 320 °C, with intermediate steps at 180 °C and 250 °C—each held for 30 min. The final temperature of 320 °C is maintained for 3 h to achieve complete PI imidization.

Following this, a peeling pattern is created on the PI layer by spin-coating RDP-2100P photoresist. The spin-coating parameters are set to low-speed rotation at 500 rpm for 5 s and high-speed rotation at 3000 rpm for 60 s, resulting in a thickness of 6 μm. An exposure dose of 120 mJ is applied, and TMAH (1:6 with deionized water) is used for development over 70 s to form the thermoelectric functional layer pattern.

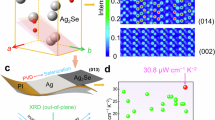

Next, the thermoelectric functional layer is prepared. DC sputtering is performed for Ag2Se with a power of 80 W, a pressure of 2.0 Pa, and a duration of 1 h, yielding a layer thickness of 1.2 μm. The thickness ratio of the Ag2Se layer to the photoresist layer exceeds 1:3, suitable for the lift-off process. After sputtering, the excess RDP-2100P photoresist and Ag2Se are removed using acetone, retaining only the Ag2Se in the desired pattern. The layer is then annealed in a vacuum at 300 °C for 30 min. The lithography and development processes are repeated for the photoresist before sputtering MgAgSb under similar conditions—80 W power, 3.7 Pa pressure, and 1 h duration, achieving a thickness of 1.2 μm. After sputtering, the excess photoresist and.

MgAgSb are stripped, followed by annealing at 350 °C for 30 min in a vacuum29,30.

In the seventh step, electrodes are prepared by spin-coating RDP-2100P photoresist corresponding to the PI pattern, following the same spin-coating and development process as before. A copper (Cu) metal seed layer with a thickness of 200 nm is sputtered to prepare for electroplating. Electroplating is conducted symmetrically on the 3-inch silicon wafer for four cycles at a current of 0.8 A for 5 s each cycle. Following electroplating, a lift-off process is carried out to remove excess photoresist and Cu, leaving only the patterned Cu metal intact. The process for preparing the other side electrode is identical, involving the selection of a different mask and following the same lithography and electroplating procedures.

Finally, PDMS encapsulation is performed. The PDMS is mixed with a curing agent at a 10:1 ratio, thoroughly stirred, and vacuum degassed. The mixed PDMS is then dropped onto the thermoelectric functional layer and spun at 1000 rpm for 30 s, resulting in a thickness of 100 μm. This is cured in a vacuum drying box at a constant temperature of 60 °C for one hour.

The last step involves device lift-off. The prepared silicon wafers are immersed in dilute hydrochloric acid with a molar ratio of 1:4, which corrodes the Al sacrificial layer while the PI and PDMS remain unaffected, thereby protecting the electrode and thermoelectric functional layer.

FTEG characterization

The surface and cross-section of the thermoelectric functional layer were characterized using electron microscopy. To evaluate the output performance of the flexible thermoelectric generator (FTEG), a dedicated test platform was constructed. The hot end of the FTEG is regulated by a heated stage, while the cold end is managed by a commercial Peltier device. The temperature control module (TCM-1030) ensures precise regulation of the Peltier temperature, achieving an accuracy of 0.01 °C. A sliding rheostat serves as the load resistance for the FTEG. A digital multimeter (GDM-9061) is used to record the load voltage of the device at various resistances and temperatures. The output power of the FTEG is subsequently calculated using the measured voltage and load resistance.

Result and discussion

The lift-off technology has excellent pattern control. The prepared flexible thermoelectric devices are shown in the Fig. 5 a. As shown the Fig. 5b, c, the surface of Ag2Se and MgAgSb. The diagram shows that Ag2Se and MgAgSb are in good condition and match the design dimensions. In the Fig. 5d, it can be seen from the cross section of the device that the thicknesses of Ag2Se and MgAgSb are 1.2 μm . Lift-off technology enables precise and accurate pattern lift-off of thermoelectric functional layers. During the annealing process, the grains of the material will be rearranged, and the internal stress will be released, which leads to the decrease of the thickness of the material. The mapping of the SEM image can be seen in Fig. 6, where Cu is used as an electrode on both sides of the film, and the Ag element is contained in a group of adjacent units because it is contained in both compounds, but the mapping colour of the Ag element in the Ag2Se unit is heavier because of the difference in the Ag at% ratio between Ag2Se and MgAgSb. The rest of the elements are uniformly distributed in their respective regions.

Figure 7a shows the open-circuit voltage test results of the device. It can be seen from Fig. 7b that the open circuit voltage of the device maintains a good linear relationship with the temperature. This indicates that the output voltage of the device follows the formula

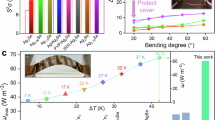

Where S represents the Seebeck coefficient, V denotes the voltage, and T signifies the temperature, thereby demonstrating the device’s capacity to generate voltage in response to temperature difference. These results confirm its effective performance in converting temperature difference into electrical energy. When the ΔT is 50 °C, the open circuit voltage of the device is 0.46 mV. Figure 7c is the test diagram of the output power density of the device. When the load resistance is the same as the internal resistance of the device, the output power of the device is the largest. Therefore, the internal resistance of the actual device is 28.9 KΩ. It is larger than the expected internal resistance. The reason may be due to the ohmic contact between the metal electrode and the thermoelectric material layer and the uncontrollable oxidation of the thermoelectric material layer. The dependence of the output power density of the device on temperature is shown in the figure. The output power of the device is calculated by the output voltage and load resistance of the device. When the temperature difference is 5 K, the maximum output power density of the device is 3.39 µW/m2. Due to the relationship of P = V2/R, and then according to Eq. (8), the output power is quadratically related to the temperature difference, which is shown in Fig. 7d as a function of the temperature difference. It shows that the output power of the device also increases nonlinearly according to the increase of temperature difference.

In addition, as a flexible thermoelectric device, the flexibility of the device should also be considered. As shown in the figure, the device is bent on a glass rod with a radius of 4 mm. After 800 bending cycles, the conductivity of the device decreased to 88% of the original, which may be due to the fracture of the ohmic contact between the electrode and the thermoelectric functional layer. The environmental adaptability of the device was tested. In the glove box, the device was tested in high humidity environment. The resistance and output performance of the device were tested by using a humidifier to humidify and simulate different humidity environments. As shown in the Fig. 8b, the resistance of the device remains basically unchanged in high humidity environment. At 80 humidity, the conductivity of the device decreases, which may be due to the oxidation of the external electrode, resulting in the increase of the overall resistance of the device. In addition, the high temperature service characteristics of the device in the air environment were also studied. The resistance of the device in an air environment was also investigated as a function of temperature, and the conductivity of the device was tested by holding it at different temperatures for 30 min. As shown in Fig. 8c, the overall internal resistance of the device decreases with increasing temperature. the conductivity of Ag2Se and MgAgSb is dependent on temperature, with the conductivity increasing with increasing temperature29,30. An increase in the conductivity of the thermoelectric functional layer leads to a decrease in the overall resistance of the device. In summary, the FTEG shows strong performance and adaptability under a variety of conditions, maintaining conductivity under high humidity conditions, and resistance reduction at elevated temperatures will show higher efficiency.

Conclusion

This paper presents a method for fabricating flexible Y-type thermoelectric devices that leverage MEMS-controlled lift-off technology. The thermoelectric unit, composed of Ag2Se/MgAgSb, features a functional layer created through magnetron sputtering, resulting in a dense film. This lift-off technique offers several advantages over traditional etching methods, such as ease of use, reduced fabrication costs, and the ability to produce large-area components. Through COMSOL simulations, the optimal dimensions for the thermoelectric unit were identified as 800 nm in length and 600 nm in width. The innovative Y-type structure effectively enhances the integration and collection of larger temperature gradients within flexible thermoelectric devices. At a temperature difference of 50 K, an output voltage of 0.49 mV was achieved, while an output power density of 3.39 µW/m² was obtained at a specified temperature difference of 5 K. Moreover, the device demonstrates impressive flexibility; even after being bent 800 times around a glass rod with a diameter of 4 mm, its conductivity decreases by only 12%. It also exhibits excellent stability under harsh environmental conditions. The successful integration of MEMS lift-off miniaturization and large-area applications in the field of thermoelectrics, paving the way for future advancements in this area.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during thecurrent study available from the corresponding authoron reasonable request.

References

Xie, H., Zhang, Y. & Gao, P. Thermoelectric-powered sensors for internet of things. Micromachines (Basel) 14 (1), 31 (2022).

Guo, R. et al. A novel PDMS-Based flexible thermoelectric generator fabricated by Ag(2)Se and PEDOT:PSS/Multi-Walled Carbon nanotubes with high output performance optimized by embedded Eutectic Gallium-Indium electrodes. Nanomaterials (Basel) 14 (6), 542 (2024).

Wu, P. et al. A review on flexible Thermoelectric Technology: material, device, and applications. Int. J. Thermophys. 42 (8), 111 (2021).

Jaziri, N. et al. M. A comprehensive review of Thermoelectric generators: technologies and common applications. Energy Rep. 6, 264–287 (2020).

Wei, L. et al. Optimization and fabrication of MEMS suspended structures for nanoscale thermoelectric devices. Nanotechnology. 33, 32 (2022).

Peng, S. W., Shih, P. J. & Dai, C. L. Manufacturing and characterization of a Thermoelectric Energy Harvester using the CMOS-MEMS technology. Micromachines. 6 (10), 1560–1568 (2015).

Trung, N. H., Van Toan, N. & Ono, T. Fabrication ofπ-type flexible thermoelectric generators using an electrochemical deposition method for thermal energy harvesting applications at room temperature. J. Micromech. Microeng. 27 (12), 125006 (2017).

Zhou, W. et al. High-performance and compact-designed flexible thermoelectric modules enabled by a reticulate carbon nanotube architecture. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 14886 (2017).

Chang, P. S. & Liao, C. N. Screen-printed flexible thermoelectric generator with directional heat collection design. J. Alloys Compd. 836, 155471 (2020).

Werner, R., Matejka, J. S., Schönauer-Kamin, D. & Moos, R. From Thermoelectric Powder directly to Thermoelectric generators: flexible Bi2Te3 films on Polymer sheets prepared by the Powder Aerosol Deposition Method at Room temperature. Energy Technol. 10 (5), 2101091 (2022).

Kuang, N., Zuo, Z., Wang, W., Liu, R. & Zhao, Z. Optimized thermoelectric properties and geometry parameters of annular thin-film thermoelectric generators using n-type Bi2Te2.7Se0.3 and p-type Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3 thin films for energy harvesting. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 332, (2021).

Qu, D., Huang, X., Li, X., Wang, H. & Chen, G. Annular flexible thermoelectric devices with integrated-module architecture. npj Flex. Electron. 4 (1), 1 (2020).

Nguyen Huu, T., Nguyen Van, T. & Takahito, O. Flexible thermoelectric power generator with Y-type structure using electrochemical deposition process. Appl. Energy. 210, 467–476 (2018).

Hsin, C. L., Huang, C. W., Wu, M. H., Cheng, S. Y. & Pan, R. C. Synthesis and thermoelectric properties of indium telluride nanowires. Mater. Res. Bull. 112, 61–65 (2019).

Tynell, T., Aizawa, T., Ohkubo, I., Nakamura, K. & Mori, T. Deposition of thermoelectric strontium hexaboride thin films by a low pressure CVD method. J. Cryst. Growth. 449, 10–14 (2016).

Mukherjee, S. K., Joshi, L. & Barhai, P. K. A comparative study of nanocrystalline Cu film deposited using anodic vacuum arc and dc magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 205 (19), 4582–4595 (2011).

Zhou, Y., Li, L., Tan, Q. & Li, J. F. Thermoelectric properties of Pb-doped bismuth telluride thin films deposited by magnetron sputtering. J. Alloys Compd. 590, 362–367 (2014).

Dimaggio, E., Narducci, D. & Pennelli, G. Fabrication of Silicon Nanowire Forests for thermoelectric applications by metal-assisted Chemical etching. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 27 (12), 6279–6285 (2018).

Xu, B., Li, C., Myronov, M. & Fobelets, K. n-Si–p-Si1 – xGex nanowire arrays for thermoelectric power generation. Solid State Electron. 83, 107–112 (2013).

Sökmen, Ü. et al. Shallow and deep dry etching of silicon using ICP cryogenic reactive ion etching process. Microsyst. Technol. 16 (5), 863–870 (2010).

Kim, E. H., Xiao, Y. B., Kong, S. M. & Chung, C. W. Investigation on etch characteristics of MgO thin films using a HBr/Ar plasma. Thin Solid Films. 519 (20), 6820–6823 (2011).

Lin, H. K., Lin, R. C. & Li, C. H. Etching processes of transparent carbon nanotube thin films using laser technologies. Thin Solid Films. 518 (24), 7253–7257 (2010).

Huang, L. et al. Improving optical and electrical performances of aluminum-doped zinc oxide thin films with laser-etched grating structures. Ceram. Int. 47 (6), 7994–8003 (2021).

Loghina, L., Palka, K., Buzek, J., Slang, S. & Vlcek, M. Selective wet etching of amorphous As2Se3 thin films. J. Non-cryst. Solids. 430, 21–24 (2015).

Mani, A. et al. Wet-chemical etching of SrMoO3 thin films. Mater. Lett. 184, 173–176 (2016).

Liu, H. F., Lim, E. S., Tung, P. K. H. & Xiang, N. Fabrication and transfer of nanoporous alumina thin films for templating applications: metal dots array deposition and porous ZnO film growth. Thin Solid Films. 519 (10), 3050–3054 (2011).

Zhang, J., Irannejad, M., Yavuz, M. & Cui, B. Gold nanohole array with Sub-1 nm roughness by annealing for sensitivity enhancement of extraordinary Optical Transmission Biosensor. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 10 (1), 238 (2015).

Zhao, Y. et al. Preparation and characterization of the Ag2Se flexible films tuned by PVP for wearable thermoelectric generator. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 32 (15), 20295–20305 (2021).

Zang, J. et al. Effect of post-annealing treatment on the thermoelectric properties of Ag2Se flexible thin film prepared by magnetron sputtering method. Results Phys. 106222, 2211–3797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2023.106222 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. Effect of annealing conditions on the thermoelectric properties of magnetron sputtered MgO-Ag3Sb-Sb2O4 flexible thin films. J. Inorg. Mater. (in Chinese). 37, 12 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62371425, 62001428), the Research Project Supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (2022 − 144), the Subject Reserve young talent support program of North University of China, the special fund for Science and Technology Innovation Teams of Shanxi Province (202304051001030) .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. G.and S.W.:Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft; G.R. and G.R.: Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft; Z.W.: Visualization, Investigation; L .D.(Corresponding Author): Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.X.C.:Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, G., Shi, W., Guo, R. et al. Facile Y-type Micro Ag2Se/MgAgSb flexible thermoelectric device based on lift-off technology. Sci Rep 14, 28247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78925-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78925-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical bonding and metallurgical bonding synergistically optimize the shear properties of the Ni/Bi2Te3 joint interface

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2025)