Abstract

Sexual dysfunction (SD) is a common non-motor symptom in people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) yet underreported and undertreated specifically in many ethnic PD groups because of religious, social and personal perceptions. We conducted the first single-centre cross-sectional study in the United Arab Emirates of SD in 513 consecutive patients who agreed to complete the survey questionnaires. Data was collected on SD using the Nonmotor Symptoms Scale (NMSS), Index of Erectile Function, and Female Sexual Function Index. Our results show that the non-Emirati group had higher NMSS-SD scores than the Emirati group. SD was reported independent of ethnicity, race and disease stage (p < 0.001). SD correlated with worsening quality of life (p < 0.001) and anxiety ___domain, especially in young PD patients (p < 0.001). Our data concludes that there is no significant difference in SD between different ethnicity groups, contrary to common perception. SD appears to be underreported in this population and needs addressing using culturally sensitive bespoke counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic multisystem neurodegenerative disorder with classic features of motor problems (ranging from tremors to gait disorders) and nonmotor symptoms (NMS)1,2,3. Symptoms progress over time and increasingly impact the quality of life (QoL) with disease duration. Whilst motor symptoms remain the hallmark features of PD, NMS, including sleep disorders and autonomic dysfunction, are standard features, almost arising 15 years pre-diagnosis, known as the prodromal phase of symptoms1,2,3. Sexual dysfunction (SD) is a common NMS in PD, yet one of the most under-reported and most neglected NMS4.

Sexual health is a basic human need, fundamental to the overall health and well-being of individuals, couples, and families, forming a vital part of QoL5. SD in People with PD (PwP) is highly complex and multifaceted, encompassing a range of symptoms, including erectile dysfunction (ED), reduced libido, and issues relating to orgasm6. PwP reports that a healthy sexual life is often correlated with a good outlook and satisfaction in life7. Yet so many PwPs have their sexual health ignored and untreated due to the lack of open conversations about its impact. It is, therefore, not surprising that SD is standard amongst PwP, often linked to age, gender, and comorbidities6,8,9,10. The general population prevalence of SD is around 43% in women and 31% in men11, but this prevalence increases substantially in those with PD. Prevalence in PD men is as high as 79%, with erectile dysfunction (ED) being the most typical reported symptom6. The prevalence of SD in PD women is twice as high as the general population at 87%12.

The pathophysiology of SD in PD has been explored and encompasses a range of systems and causes (Fig. 1). These include dopaminergic depletion, endothelial dysfunction, alpha-synuclein deposits, vitamin (particularly vitamin D) levels, and anti-PD medication side effects (such as anticholinergics and dopamine agonists)13,14,15.

Ethnic differences in phenotypic expression of PD have been described16, and NMS, including SD, is a determinant of NMS17,18. However, delving into the ethnic differences in SD expression in PD patients remains lacking, with a handful of studies exploring SD in non-white PD populations such as the Middle East19,20,21. El-Sakka (2012) reviews articles on ED in Arab countries, concluding the amount of literature available, but the evidence remains lacking, with no controlled studies exploring ED in Arab men effectively. From the literature available, there was a suggestion of ED being more prevalent in Arab men, likely due to the higher prevalence of endothelial dysfunction risk factors in Arab men22. There has been more exploration of ED in men in Arab countries22,23; however, it falls short of exploring SD in women generally. Maaita et al. (2018) explore SD amongst Jordanian women, reporting SD is most significant for women with more than four children (83.3%, p < 0.02), with chronic diseases (76.7%, p < 0.02) and unemployed (76.7%, p < 0.02)24. Furthermore, they report that 64.7% of Jordanian women experience some level of SD, with lack of desire being the commonest complaint and age being the most significant risk factor.

We report data from a new survey, the EmPARK-SD project, part of the EmPark Study16, the first UAE longitudinal observational study exploring SD in Emirati-origin PD patients. We present the first set of data analyses of a much-needed topic for a population of PD patients.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

For this single-centre cross-sectional study, participants were recruited from the Movement Disorder Service at King’s College Hospital, Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), between January 2020 and January 2023. Participants underwent neurological and specific SD assessments administered by healthcare professionals. The study was approved by local ethical approval (K/D/REC/KD07/09/171) and by the UAE General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Furthermore, the study was endorsed by the UAE Parkinson’s expert group, Parkinson’s Association UAE.

Informed consent

All participants were given information on the EmPARK-SD project and ample time to consider participating. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were by the ethical standards of King’s College Hospital Dubai and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments ethical standards.

Study population

The study sample included 513 patients affected by PD according to the UK PD Society Brain Bank diagnostic criteria living in the UAE. Inclusion criteria were as follows: aged between 18 to 80 years old and HY stage 1–3. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of dementia or severe medical disorder and psychiatric disorder, as assessed by a healthcare professional, which might interfere with completing assessments. Furthermore, patients were excluded if they had severe motor fluctuations and were unresponsive to anti-PD medication or using advanced therapies, including Deep Brain Stimulation and infusion therapies. The eligibility criteria were designed to limit the variability introduced into the data by including advanced PwP (HY stage 4&5, infusion therapies, and DBS) with motor impairment, treatment side effects, and disease burden, potentially confounding the results.

Baseline, clinical, and sexual assessment

Baseline socio-demographic data was collected for all participants. This included age, PD motor subtypes, and ethnicity. We applied Ethnicity Coding as per the NHS Race and Health Observatory25 and National Clinical Coding Standards OPCS 26, with the ethnicity in our cohort defined as those identifying as either Emirati or non-Emirati. Emirati origin encompassed those from Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm Al Quwain. Non-Emirati origin was everyone else.

PD motor symptoms were assessed using the Hoehn & Yahr (HY) staging and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III. HY Stage, evaluated by the clinician, is a validated global staging system designed to assess the functional disability of PD-related motor symptoms27. HY staging is defined as 0 [no signs of disease], 1 [unilateral symptoms only], 1.5 [unilateral and axial involvement], 2 [bilateral symptoms, no impairment of balance], 2.5 [mild bilateral disease with recovery on pull test], 3 [balance impairment, mild to moderate disease, physically independent], 4 [severe disability, but still able to stand or walk unassisted], and 5 [needing a wheelchair or bedridden unless assisted at all times]. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part III is the original validated scale used to map the longitudinal course of PD28. UPDRS, a clinician-completed scale, encompasses 14 items, each scored between 0–4, with a possible total score of 56, with the higher scores associated with more symptomatic PD. PD patients had their motor symptoms evaluated for three types of PD motor subtypes: Akinetic dominant (AKD), Tremor dominant (TD), or mixed subtype, as determined by their physician after completing their UPDRS-III and neurological examination.

Neuropsychiatric status data was collected using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a patient-completed questionnaire29. HADS assessed both depression and anxiety, with each having seven questions, scored between 0 and 3, with the maximum score being 21 for anxiety and 21 for depression. Interpretation of the scoring is suggested as 0–7 (normal), 8–10 (mild), 11–15 (moderate), and 16–21 (severe).

Patient QoL is assessed using the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 8-Items (PDQ-8), the short patient-completed questionnaire30. This is an 8-item questionnaire; each question scored between 0 and 4, with the higher scores indicating poorer and more impacted QoL.

Sexual function was assessed using the three tools. Firstly, the Nonmotor Symptoms Scale Sexual Dysfunction Domain 8 (NMSS-SD), a clinician-completed scale, has nine domains, of which ___domain eight is SD-focused31. Domain 8 asks two questions, rated for severity (0-to-3) and frequency (1-to-4). We used the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) for men with PD, a validated patient-completed, multidimensional instrument widely considered the gold-standard tool for male SD, particularly ED32. IIEF is a 15-item questionnaire relating to sexual experiences over the preceding 4 weeks, with questions ranked on a 5-point scale and a cut-off of 25, with men scoring less than 25 classed as having ED. IIEF has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity. Lastly, for women with PD, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) is a validated patient-completed assessment of female SD33. FSFI has six domains, totalling 19 questions; each question is ranked on a 5-point scale; the higher the scores indicate, the greater the level of sexual functioning. As such, the cut-off score of < 26.55 is proposed as diagnosing female SD.

To avoid nonresponse and misunderstanding, all assessments were made available in either English or Arabic, as the patient preferred. Additionally, all assessments were completed in the clinic, with a healthcare professional reading, explaining, and translating for patients. Professional translators and Parkinson’s UAE provided Arabic translation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentages, mean and standard deviation) were calculated for the socio-demographic and clinical variables of the total sample. NMSS-SD scores were computed in the sample grouped by variables of interest: sex, age (by quartiles), disease duration (by the median), ethnic origin/nationality, HY stages and PD subtype, for comparisons between groups, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed. The association between the NMSS-SD scores and the rest of the continuous variables was analysed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients in the total sample and by sex and age groups. Finally, a multivariate linear regression model was run in the total sample, with the NMSS-SD score as the dependent variable, including sex, age, ethnic origin, UPDRS-3, HADS-A and HADS-D as independent variables. The same models were computed separately by sex, including the IIEF in the male subsample and the FSFI in the female subsample. All models were checked for collinearity and the linear regression model assumptions.

Results

Demographic and clinical features

513 patients diagnosed with PD were recruited from all ethnic backgrounds and grouped into either Emirati (207 patients) or non-Emirati (306 patients) cohorts. The patients’ mean age was 60.13 ± 8.12 years, with a mean disease duration of 4.66 ± 2.07 years. The Emirati cohort had 57% female patients, whilst non-Emirati had 25% female patients (Table 1).

The majority of the cohort was HY stage 2.5 and below (76.7%) and were primarily Akinetic dominant (AKD) motor subtype of PD (49.3%) (Table 2). Patients for the entire cohort were moderately symptomatic for their motor symptoms (20.94 ± 7.77), alongside bothersome SD as scored by NMSS-SD (12.45 ± 4.22). The mean FSFI score from women of the cohort suggests the diagnosis of female SD (14.71 ± 3.80, with cut-off < 27 diagnostic). However, the mean IIEF score from men was above the diagnostic criteria for ED (31.13 ± 10.69, with a cut-off < 26 diagnostics). The mean score for HADS-A suggests a moderate level of anxiety (12.05 ± 2.25), and the HADS-D mean score suggests a mild level of depression (10.45 ± 2.08) (Table 3).

Ethnicity characteristics

A Kruskal–Wallis H test showed there to be a statistically significant difference in age for the two ethnicity groups (Table 4), with Emirati PD patients being younger (p < 0.001) and having a higher proportion of women (p < 0.001) than the non-Emirati PD group. However, the two groups had no statistically significant difference in disease duration (p = 0.067).

Ethnicity differences in clinical assessments

A Mann–Whitney U test was run to determine if there were differences in clinical assessments between Emirati and non-Emirati PD patients in the EmPARK study. Mean NMSS-SD scores differed between the two ethnic groups, whereby the non-Emirati group had higher NMSS-SD scores than the Emirati group, but this was not statistically significant U = 344,389.000, z = 1.679, p = 0.093,. However, the mean HADS-A was significantly higher in the Emirati group compared to the non-Emirati group (HADS-A U = 26,183.000, z = -3.457,p < 0.001), whilst Non-Emirati had significantly higher mean HADS-D (U = 36,296.000, z = 3.005, p = 0.003) the mean results of other clinical assessment scores, UPDRS-III, PDQ-8, IIEF, and FSFI, were not statistically significant between the two ethnic groups (Table 5).

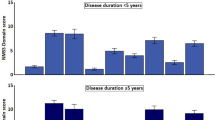

NMS scale sexual dysfunction ___domain variability

A Mann–Whitney U test determined there were no statistically significant differences in the median NMSS-SD scores between gender (U = 28,745, z = -1.411, p = 0.158) and ethnicity (U = 34,389, z = 1.679, p = 0.093). However, median NMSS-SD scores were higher, with longer disease duration equal to or more than 6 years (U = 33,834, z = 3.945, p < 0.001) (Table 6).

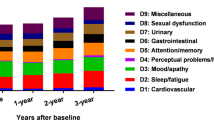

A Kruskal–Wallis H test was run to determine whether NMSS-SD scores differed between the participants’ HY stage, PD motor subtype, and age (Table 6). Participants were grouped into three possible groups of HY stages (HY stage [mild] 1–1.5, [moderate] 2–2.5, and [severe] 3–3.5); there were no participants with HY stage 4 or above. There was a statistically significant difference between all three groups in their median NMSS-SD scores, with the scores being higher with more severe HY stages (H (2) = 33.185, p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between mean NMSS-SD scores and the three types of PD motor subtypes (AKD, TD, and Mixed subtype) (H (2) = 2.105, p = 0.349). There was a statistically significant difference in mean NMSS-SD scores between age quartiles, whereby the NMSS-SD score increases with age, with the highest mean score (13.66) observed in the 67 and over age group. This group had the highest mean score and a relatively low SD (4.16), indicating a consistent trend in this category. There is a clear difference between age groups, driven mainly by the older age group (H (2) = 12.438, p < 0.006) (Fig. 2).

Association of NMSS-SD scores

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was applied to find any association between NMSS-SD scores and variables, including age, disease duration, and clinical tools (Table 7). NMSS-SD scores have a moderate positive correlation with IIEF (rs = 0.356, p < 0.01) and FSFI (rs = 0.329, p < 0.01) scores. However, a weak positive correlation exists between NMSS-SD scores and UPDRS-III, PDQ8, age, and HY stages. The association with NMSS-SD scores, when grouped by gender, was like the total sample; however, the association of NMSS-SD scores with PDQ-8 was higher in women than in men. Association with NMSS-SD scores when groups by age limit of 60 yielded a higher correlation coefficient between NMSS-SD and FSFI in younger PD patients (rs = 0.42, p < 0.01). For older PD patients, the NMSS-SD correlation was higher with disease duration (rs = 0.30, p < 0.01) and IIEF scale scores (rs = 0.36, p < 0.01).

Multivariate linear regression analysis

A multiple regression was run to predict NMSS-SD scores from UPDRS-III, age, and HADS-A scores. The multiple regression model statistically significantly predicted NMSS-SD scores, F (3, 509) = 12.693, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.064. All three variables added statistically significantly to the prediction of NMSS-SD scores, p < 0.05 (Table 8). A further analysis was run with disease duration and UPDRS-III scores, which showed statistically significant predictive value for NMSS-SD scores, F (2, 510) = 21.062, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.073 (Table 9). Therefore, the main determinants of NMSS-SD scores for the total sample are age, UPDRS-III scores, and HADS-A. However, with the inclusion of disease duration in the models, age and HADS-A variables are not significant.

A further analysis was performed to explore the ability to predict NMSS-SD scores of men with PD in the cohort from IIEF, disease duration, UPDRS-III, and ethnicity groups. The variables were statistically significant in predicting NMSS-SD scores for the men cohort, F (4, 312) = 20.368, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.197 (Table 10). Lastly, the variables of FSFI score, UPDRS-III score, and disease duration were analysed for the women cohort, reporting these variables to be statistically significant in predicting NMSS-SD scores for the women cohort, F (3, 191) = 13.401, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.161 (Table 11).

Descriptive analysis against age and gender

There were statistically significant differences between men and women in their PDQ-8, HADS-A, and HADS-D scores, whereby men had higher scores for PDQ-8 and HADS-D, whilst women had higher scores for HADS-A. Additionally, the data finds UPDRS-III scores, NMSS-SD and HADS-D scores to be significantly higher in the older PD patients, whilst HADS-A were significantly higher in younger patients (Table 12). The IIEF scores showed no significant difference between age groups (p = 0.172), and there were no gender comparisons available for the measure. Similarly, FSFI did not show a significant difference between age groups (p = 0.809).

Discussion

This extensive survey of Emirati and non-Emirati PD patients attending a specialised UAE PD clinic shows the following key results:

-

NMSS SD ___domain can identify and signpost patients with SD in PD and underscores the need for using validated tools such as NMSS in clinical practice where possible

-

Mean NMSS-SD scores were higher in the non-Emirati group than in the Emirati group.

-

There were no statistically significant differences in the median NMSS-SD scores between gender and ethnicity. Still, median NMSS-SD scores were higher, with longer disease duration equal to or more than 6 years.

-

NMSS-SD scores were higher in patients with more severe HY stages, and the NMSS-SD score was higher in older patients.

-

NMSS-SD scores associated with PDQ-8 were higher in women than in men.

-

UPDRS-III, age, and HADS-A scores were statistically significant in predicted NMSS-SD scores.

SD is a common under-recognised and under-reported significant NMS which has a great impact on PD patients QoL7,34. The lack of discussion around SD between clinicians and patients leads to this important NMS going unexplored35. Ethnicity poses a further problem, with cultural differences stigmatising the discussions and making the assessment and treatment of SD difficult. Other key elements impacting the evaluation of SD include the pathophysiology of SD, whereby PD patients are often more likely to experience SD with increasing age for both genders36. Furthermore, SD pathophysiology is complex, with multiple mechanisms being involved, ranging from autonomic dysfunction, dopaminergic deficiency and medication side effects13. The EmPark-SD project adds to the much-needed data on SD in different ethnic groups of PD patients, emphasising the ability to incorporate SD assessment in clinical practice.

The EmPark-SD encompasses the inclusion of patients from the Middle East, such as the UAE, whereby much of the socioeconomic, gender, and cultural factors which can impact SD assessment are imposed. The Emirati cohort of PD patients was found to be younger and had more women than the non-Emirati cohort. Our results show that non-Emiratis have higher NMSS-SD scores than Emiratis, but this was not statistically significant. This could be because SD may be underreported in our Emirati cohort for both men and women; this is likely due to the culturally sensitive nature of SD. Given SD is often associated with ED, much of the SD which women can face is frequently overlooked. Additionally, young PD patients find SD to be an essential aspect of their QoL, and not evaluating SD in PD patients fails their care and falls short of providing a holistic approach37,38,39. Previous studies have confirmed that SD within the PD population is more common and significantly impacts QoL than healthy controls7,34.

Our study shows that SD assessment readily applies to clinical practice using the validated NMSS, which incorporates SD questions (___domain 8). Our study confirms that NMSS-SD scores correlate with IIEF and FSFI. As such, simply adding NMSS to clinical practice allows for SD assessment in two easy, quick questions. Clinicians may avoid or feel uncomfortable assessing SD. However, PD patients report SD assessment to be core to their QoL and often would use the opportunity to discuss with a clinician their symptoms if given the option. Our regression analysis suggests the main determinants of NMSS-SD to be age, UPDRS-III, and HADS-A.

Previous studies have reported SD as a significant problem with increasing disease duration and age20,40. SD is often under-recognised in the older population, yet it significantly impacts QoL and psychological well-being. Lindau et al. (2007) show in their cohort that older patients rated their health as poor and were less likely to be sexually active41. Our study with evidence of NMSS-SD scores significantly higher in older patients and increased disease duration. We show that NMSS-SD and FSFI had a higher correlation in younger PD patients, whilst, in older patients, NMSS-SD was associated with longer disease duration and higher IIEF scores. This is not surprising as disease duration and SD burden have been described previously4,42, but more interesting is that our study provides a new insight into the impact of SD on younger patients.

Gender has been proposed to play a crucial part in SD, whereby women often underreport SD than men43. This becomes a great challenge as our study shows women to have slightly higher NMSS-SD scores than men. Women also had higher PDQ-8 scores than men in our overall cohort, suggesting that SD may have a more significant impact on women’s QoL than previously reported. Women in our study were found to have higher HADS-A scores, whilst men were found to have higher HADS-D and PDQ-8 scores. The association of NMS burden on PD QoL and disease severity has been well described7,35. Given the impact of mood on general QoL as assessed by the PDQ-8, the emergence of SD may be affecting worsening mood symptoms, anxiety for women and depression for men.

PD severity has been shown to correlate with SD in PD patients. Our study complements previous studies20,44, finding that NMSS-SD scores are higher in more severe HY stages and higher UPDRS-III scores. There is an important point to consider: better motor control of PD symptomology may help manage SD symptoms better. Our study also explored PD motor subtypes; our cohort had higher AKD subtypes. Previously, the Postural Gait and Instability Dominant (PIGD) subtype have been described as having severe motor symptoms with higher NMS burden, with SD being a common problem45. Our study did not have any patients identified as PIGD subtype, and our study had no patient’s HY stage greater than 3.5. As such, there is space to explore the correlation of motor subtypes and SD in a great PD population group. Further evaluation of the impact of treatment on SD is required to appreciate the potential side effects of anti-PD drugs but also the potential benefit of better motor control.

SD has yet to be extensively investigated in various cultures and a culturally bespoke manner. To date, there have been no studies published highlighting PD-related SD in the Middle East. We present the first UAE-based analysis of the ongoing EmPark-SD study, focusing on SD in the Middle East PD population. Our study adds to existing data showing a difference in SD for gender and ethnicity. The Middle East PD population is growing and provides an opportunity to ensure the integration of SD assessment in clinical practice as a standard format for care. Our study shows that the NMSS is a valid and valuable tool for effectively evaluating SD in clinical practice.

Our study, the first analysis of the EmPark-SD project, has some limitations. The assessments fall short of evaluating the type of SD and particular SD symptoms experienced by the different ethnic groups and genders. FSFI and IIEF scales both assess patients with a partner and having regular intercourse four weeks before the completion of scales; as such, this fails to capture those without partners and non-sexually active. Our study would be enhanced by including the concerns and experiences of the patient’s partner, contributing to the overall understanding of how SD impacts PD relationships. Lastly, our data does not include the patient’s socioeconomic status, total NMS scale scores, and details of treatments. This should be included in future EmPark-SD study data set reports. Despite these limitations, our study adds to the field of PD to understand the importance of SD assessment and its impact on our PD patients.

This first dataset analysis of the UAE EmPark-SD project outlines that Emirati PD patients have more women and younger patients. The Emirati cohort likely has underreported SD compared to non-Emirati patients. Our data shows a higher rate of SD associated with higher disease severity, NMS burden, and older patients. Furthermore, we find the NMSS a useful clinical tool, with ___domain 8 assessing SD with two questions, which can apply to clinical practice in assessing SD in PD patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Storch, A. et al. Quantitative assessment of non-motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease using the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS). J Neural Transm (Vienna) 122(12), 1673–1684 (2015).

Prakash, K. M. et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the quality of life of Parkinson’s disease patients: A longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol 23(5), 854–860 (2016).

Tibar, H. et al. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and their impact on quality of life in a cohort of Moroccan patients. Front Neurol 9, 170 (2018).

Kinateder, T., et al. Sexual dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease and their influence on partnership-data of the PRISM Study. Brain Sci 12(2) (2022).

Coleman, E. Sexual health for the millennium: An introduction. International Journal of Sexual Health 20(1–2), 1–6 (2008).

Bronner, G. et al. Sexual dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Sex Marital Ther 30(2), 95–105 (2004).

Barone, P., Erro, R. & Picillo, M. Quality of life and nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 133, 499–516 (2017).

Zesiewicz, T. A., Helal, M. & Hauser, R. A. Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) for the treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 15(2), 305–308 (2000).

Celikel, E. et al. Assessment of sexual dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study. Eur J Neurol 15(11), 1168–1172 (2008).

Hand, A. et al. Sexual and relationship dysfunction in people with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 16(3), 172–176 (2010).

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A. & Rosen, R. C. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA 281(6), 537–544 (1999).

Varanda, S. et al. Sexual dysfunction in women with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 31(11), 1685–1693 (2016).

Batzu, L. et al. The pathophysiology of sexual dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: An overview. Int Rev Neurobiol 162, 21–34 (2022).

Metta, V., Sanchez, T. C. & Padmakumar, C. Osteoporosis: A hidden nonmotor face of Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 134, 877–890 (2017).

Taloyan, M. et al. Association between sexual dysfunction and vitamin D in Swedish primary health care patients born in the Middle East and Sweden. Sci Rep 14(1), 594 (2024).

Metta, V. et al. First two-year observational exploratory real life clinical phenotyping, and societal impact study of Parkinson’s disease in Emiratis and expatriate population of United Arab Emirates 2019–2021: The EmPark Study. J Pers Med, 2022. 12(8).

Rana, A. Q. et al. Impact of ethnicity on non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2(4), 281–285 (2012).

Sauerbier, A. et al. Clinical non-motor phenotyping of black and asian minority ethnic compared to white individuals with Parkinson’s disease living in the United Kingdom. J Parkinsons Dis 11(1), 299–307 (2021).

Elshamy, A. M. et al. Sexual dysfunction among Egyptian idiopathic Parkinson’s disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 35(6), 816–822 (2022).

Deraz, H. et al. Sexual dysfunction in a sample of Egyptian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci 45(3), 1071–1077 (2024).

Shalash, A. et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with Parkinson’s disease: Related factors and impact on quality of life. Neurol Sci 41(8), 2201–2206 (2020).

El-Sakka, A. I. Erectile dysfunction in Arab countries. Part I: Prevalence and correlates. Arab J Urol 10(2), 97–103 (2012).

Khalaf, I. M. & Levinson, I. P. Erectile dysfunction in the Africa/Middle East Region: Epidemiology and experience with sildenafil citrate (Viagra). Int J Impot Res 15(Suppl 1), S1-2 (2003).

Maaita, M. E. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of female sexual dysfunction among Jordanian women. J Family Med Prim Care 7(6), 1488–1492 (2018).

NHSRHO. Ethnicity Coding in English Health Service Datasets. 2021 [cited 2024 01/MAY/2024]; Available from: https://www.nhsrho.org/research/ethnicity-coding-in-english-health-service-datasets/.

OPCS, National Clinical Coding Standards OPCS-4 (2022). 2022.

Hoehn, M. M. & Yahr, M. D. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 17(5), 427–442 (1967).

Palmer, J. L. et al. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale-motor exam: Inter-rater reliability of advanced practice nurse and neurologist assessments. J Adv Nurs 66(6), 1382–1387 (2010).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6), 361–370 (1983).

Peto, V., Jenkinson, C. & Fitzpatrick, R. PDQ-39: A review of the development, validation and application of a Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire and its associated measures. J Neurol 245(Suppl 1), S10–S14 (1998).

van Wamelen, D. J. et al. The non-motor symptoms scale in Parkinson’s disease: Validation and use. Acta Neurol Scand 143(1), 3–12 (2021).

Rosen, R. C. et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 49(6), 822–830 (1997).

Wiegel, M., Meston, C. & Rosen, R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther 31(1), 1–20 (2005).

Santa Rosa Malcher, C.M., et al., Sexual Disorders and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease. Sex Med, 2021. 9(1): p. 100280.

Chaudhuri, K. R. et al. The burden of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease using a self-completed non-motor questionnaire: a simple grading system. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 21(3), 287–291 (2015).

Kim, H. S. et al. Nonmotor symptoms more closely related to Parkinson’s disease: Comparison with normal elderly. J Neurol Sci 324(1–2), 70–73 (2013).

Sandeep, M. et al. Sexual dysfunction in men with young onset Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 131(2), 149–155 (2024).

Wielinski, C. L. et al. Sexual and relationship satisfaction among persons with young-onset Parkinson’s disease. J Sex Med 7(4 Pt 1), 1438–1444 (2010).

Vela-Desojo, L. et al. Sexual dysfunction in early-onset Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional, multicenter study. J Parkinsons Dis 10(4), 1621–1629 (2020).

Raciti, L. et al. Sexual dysfunction in Parkinson disease: A multicenter Italian cross-sectional study on a still overlooked problem. J Sex Med 17(10), 1914–1925 (2020).

Lindau, S. T. et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 357(8), 762–774 (2007).

Vafaeimastanabad, M. et al. Sexual dysfunction among patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 117, 1–10 (2023).

Prabhu, S. S., Hegde, S. & Sareen, S. Female sexual dysfunction: A potential minefield. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS 43(2), 128–134 (2022).

Benigno, M. D. S., Amaral Domingues, C. & Araujo Leite, M. A. Sexual dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of the arizona sexual experience scale sexual dysfunction in parkinson disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 36(2), 87–97 (2023).

Deng, X. et al. Sexual dysfunction is associated with postural instability gait difficulty subtype of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 262(11), 2433–2439 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Parkinson’s Centre of Excellence King’s Dubai team (Therese Masagnay, Dr Hasna Hussein, Mr Afsal Nalarakettil, Mr Ehabadly Awad) and PD patients attending the King’s College Hospital Dubai. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank King’s College Parkinson’s Centre of Excellence London UK Research and Clinical team for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.M. conceptualised the project and the methodology. V.M. and K.R.C. led the data curation, and all other authors contributed to the data collection. C.R.B., V.M., and M.Q. analysed the dataset. V.M. and M.Q. wrote the first draft of the article. All authors were equally involved in the subsequent draft edits and reviews.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Metta, V., Ibrahim, H., Qamar, M.A. et al. The first cross-sectional comparative observational study of sexual dysfunction in Emirati and non-Emirati Parkinson’s disease patients (EmPark-SD) in the United Arab Emirates. Sci Rep 14, 28845 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79668-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79668-6