Abstract

To investigate the potential association between body mass index (BMI) and the clinicopathological features of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). We retrospectively analyzed data from 2541 patients who underwent partial or radical nephrectomy for renal masses between 2013 and 2023 in a single institution. Patients were divided into normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups based on the Chinese BMI classification. Clinicopathological features, including pathologic tumor size, pathologic T (pT) stage, Fuhrman grade or WHO/ISUP grade, renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus were compared among the groups using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, and the chi-square or Fisher’s test for categorical variables. A total of 2541 ccRCC patients having a median BMI of 24.9 (interquartile range 22.7–27.0) were evaluated. No significant association was found between the pathological tumor diameter and BMI among the normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups (normal-weight vs. overweight, p = 0.31; normal-weight vs. obese, p = 0.21). There was no statistical difference in pT stage (normal-weight vs. overweight, p = 0.28; normal-weight vs. obese, p = 0.23). No statistically significant difference was observed in the distribution of Fuhrman/ISUP grade (p = 0.12), proportion of patients with renal capsular invasion (p = 0.49), perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion (p = 1.00), and vein cancerous embolus (p = 0.11) between the normal-weight and overweight groups. However, patients in the obese group tended to have low Fuhrman or WHO/ISUP grades (p < 0.001), and decreased rates of renal capsular invasion (p < 0.05), perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion (p < 0.05), and vein cancerous embolus (p < 0.05). Obesity was associated with less aggressive pathological features such as low tumor nuclear grade, low rate of renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus. This finding may provide clinicopathological evidence and explanations for the “obesity paradox” of RCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the most common tumors in the urinary system, with its incidence increasing annually1. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) accounts for approximately 80% of all RCC cases2. Typically, ccRCC is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of lipid droplets within tumor cells, which is closely related to the unique mechanism of lipid metabolism within these tumors3.

Obesity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to an individual’s health4. It is characterized by a high body mass index (BMI), a simple weight-for-height index commonly used to classify overweight and obese adults. In recent years, the number of individuals affected by obesity has increased globally. The increase in obesity rate is a significant public health concern because of its association with numerous health complications, including heart disease, diabetes, and certain types of cancer5.

Previous studies have highlighted obesity as a risk factor for developing RCC6,7,8,9. Recent cohort studies across different ethnic groups in epidemiology have demonstrated that the hazard ratio for the obese population versus the normal-weight population was 2.16 and 1.77, respectively6,10. However, it is paradoxical that many studies have found that obesity is associated with a better prognosis in patients with RCC11,12. Several researchers suggest that the “obesity paradox” may be associated with immunity, metabolism, epigenetic alterations, and tumor microenvironment reshaping7,13,14,15. However, the mechanism of the “obesity paradox” in RCC remains unclear.

Furthermore, although transcriptomic signatures related to the “obesity paradox” in patients with ccRCC have been documented16, and some studies have reported associations between BMI and general pathological features such as tumor stage and grade17,18,19, the specific relationship between BMI and detailed pathological indices, including renal capsular invasion, sinus fat invasion, and vein embolus, remains understudied. Therefore, in this study, we performed a detailed analysis of the potential associations between BMI and the clinicopathological features of clinically localized renal masses in a large cohort.

Patients and methods

Cohort

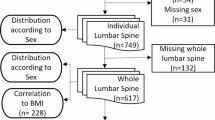

We reviewed the records of patients who underwent partial or radical nephrectomy for renal masses between 2013 and 2023 at Changhai Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University Ethics Committee waived the need of obtaining informed consent. Patients with pathological subtypes other than ccRCC, distant metastases, or incomplete data were excluded. A total of 2541 patients with pathologically confirmed ccRCC were included in the final cohort eligible for the current analysis.

The patients were divided into three groups based on the Chinese BMI classification20,21. The groups included normal-weight (BMI<24), overweight (24 ≤ BMI<28), and obese (BMI ≥ 28). The pathological variables compared among these groups included pathological tumor diameter, pathological T (pT) stage, Fuhrman, or WHO/ International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grades, renal capsular invasion, perirenal or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus. The pT stage was divided into eight categories, pT1a, pT1b, pT2a, pT2b, pT3a, pT3b, pT3c, and pT4. The Fuhrman and WHO/ISUP grades were merged into one variable, as almost all patients had one or the other grade to evaluate nuclear morphometry. Notably, patients in earlier years were more likely to have Fuhrman grades, while others tended to use the WHO/ISUP grades. The WHO/ISUP grade was preferred for inclusion if a patient had both grades. The variable representing vein cancerous embolus indicated the presence of either renal venous or vena cava thrombosis.

Statistical analysis

The retrieved variables included patient sex, age, height, weight, BMI, pathologic tumor size, pT stage, Fuhrman grade, WHO/ISUP grade, renal capsular invasion, perirenal or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA, while categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher’s test. Continuous variables were reported as the median and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were denoted as absolute numbers (n) with relative percentages (%). All tests were two-tailed, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.

All methods of this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

Of the 3856 available records, 2541 met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed after obtaining Institutional Review Board approval. The baseline characteristics of the entire cohort are presented in Table 1. The median age and BMI were 58 (50–67) years and 24.9 (22.7–27.0) kg/m2, respectively. The male-to-female ratio was 2.5:1. Moreover, 424 (16.7%) patients were smokers, 1119 (44.0%) had a diagnosis of hypertension, and 381 (15.0%) had a diagnosis of diabetes. Based on the Chinese BMI classification, 1000 (39.4%), 1096 (43.1%), and 445 (17.5%) patients were divided into normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups, respectively. Notably, the male-to-female ratio (p < 0.001) and smoking rate (p < 0.01) were higher, and comorbidities such as hypertension (p < 0.001) and diabetes (p < 0.01) were more prevalent in the overweight and obese groups than in the normal-weight group. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, used to assess preoperative fitness, showed no significant differences between the groups.

Correlation between BMI and pathological diagnosis in patients with ccRCC

Pathological parameters were compared among the three BMI groups, and the results are shown in Table 2. No significant association was found between pathological tumor diameter and BMI among the normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups (normal-weight vs. overweight, p = 0.31; normal-weight vs. obese, p = 0.21). No statistical difference was observed in the pT stage (normal-weight vs. overweight, p = 0.28; normal-weight vs. obese, p = 0.23). However, there were significant differences in the distribution of Fuhrman/ISUP grade, proportion of patients with renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus confirmed by pathology between the normal-weight and obese groups. However, there was no statistical difference in the distribution of Fuhrman/ISUP grade (p = 0.12), the proportion of patients with renal capsular invasion (p = 0.49), perirenal or renal sinus fat invasion (p = 1.00), or vein cancerous embolus (p = 0.11) between the normal-weight and overweight groups. Furthermore, patients in the obese group tended to have low Fuhrman or WHO/ISUP grades (p < 0.001), and decreased rates of renal capsular invasion (p < 0.05), perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion (p < 0.05), and vein cancerous embolus (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The incidence of RCC has increased in recent years, and obesity, a known risk factor for RCC, is becoming increasingly common. An intriguing paradox exists wherein obesity not only increases the risk of developing RCC but is also associated with a better prognosis in patients with RCC. The mechanism of this “obesity paradox” in RCC is poorly understood. However, the correlation between BMI and the characteristics of RCC remains controversial. Considering the confounding factors caused by different subtypes that usually correspond to varying degrees of malignancy22,23, we aimed to investigate the association between BMI and the clinicopathological characteristics of ccRCC, the most common RCC subtype. We compared pathological characteristics—including pathological tumor diameter, pT stage, Fuhrman or WHO/ISUP grade, renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus which are closely associated with the prognosis in patients with RCC treated with surgery, among the patients classified into normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups based on the Chinese BMI classification.

Notably, in our cohort, the mean age of the obese group was 55 years, which was lower compared to other groups. The overweight and obese groups also exhibited higher male-to-female ratios. Peired et al.24 revealed that males are twice as likely to develop kidney cancer as females. In our study, males accounted for over three times the number of females in both the overweight and obese groups and roughly twice the number in the normal-weight group. This suggests that RCC susceptibility to sex may be amplified by a high BMI. Sun et al.25 suggested that estrogen plays an important role in the etiology of RCC and may modify the association between obesity and RCC risk in women. Moreover, we found that the overweight and obese groups had a higher proportion of smokers than the normal-weight group. This trend extended to comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, with overweight and obese patients being more prone to smoking and these health conditions. However, no significant difference was observed in the ASA score, which was used to evaluate the preoperative fitness of patients.

Regarding pathological diagnosis, our study did not reveal significant differences in pathological tumor diameter or pT stages among the normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups, which is consistent with the findings of Tsivian et al.18 However, Choi et al.26 revealed that overweight and obese patients had smaller tumors in a clinical cohort of 1543 patients with RCC. Jeon et al.19 reported that these patients had a lower pT stage than normal-weight patients. In addition, we demonstrated a significant difference in the distribution of tumor nuclear grades, as evaluated by the Fuhrman or WHO/ISUP grades. Specifically, high BMI was associated with low nuclear grade in patients with ccRCC. The obese group had a significantly higher rate of low nuclear grade than the normal-weight group, whereas the overweight group exhibited a higher rate of low nuclear grade, though this difference was not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with Tsivian et al.’s study, that included all kidney cancer subtypes18. They revealed that a higher BMI was associated with a lower Fuhrman grade of RCC in clinically localized renal masses, and partly explained the better survival rates in patients with higher BMI. Although Seon et al.27 did not find any significant association between nuclear grade and BMI in a cohort of 2329 patients who underwent curative surgery for RCC, they reported that 55.6% of patients with Fuhrman grade 1–2 were in the normal-weight group, 58.8% in the overweight group, and 61.6% in the obese group (p = 0.062). Furthermore, we found that the rates of renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus were significantly lower in the obese group than in the normal-weight group. No significant difference was observed between the overweight and normal-weight groups. According to available research28,29,30,31,32,33, the presence of renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, or vein cancerous embolus is strongly associated with RCC prognosis after surgery, especially in terms of overall survival and postoperative local recurrence or distal metastasis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report an association between BMI and renal capsular invasion, sinus fat invasion, and vein embolus, which are key pathological indices influencing the prognosis of patients with RCC. Many studies have shown that obese patients with RCC have longer overall survival and cancer-specific survival6,11,27,34, including those with metastatic RCC35,36. A prospective trial conducted by Donin et al.37 revealed that obese patients had significantly improved overall survival compared with normal-weight patients in a cohort of high-risk patients with RCC from 14 countries. Nevertheless, the mechanism of the “obesity paradox,” where obesity increases the risk of developing RCC while being associated with a better prognosis, remains unclear. Our findings may partly explain the better prognosis in patients with higher BMI and “obesity paradox” in RCC. Obese patients showed less aggressive pathological features, such as low tumor nuclear grade and low rates of renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus, and therefore presented better overall survival and cancer-specific survival outcomes.

The results of our study should be carefully interpreted and prospectively validated because of some limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study could have introduced an inherent selection bias. For instance, 3856 records of patients with ccRCC were available; however, 1315 records were excluded because of incomplete data. In addition, the BMI data was preoperative, and we did not consider BMI changes in the early years of surgery or postoperative BMI changes. Second, our cohort spanned over ten years, which could have introduced unintended errors in data collection and inconsistencies in recording indices. For example, the Fuhrman grade was preferred to evaluate tumor nuclear grade in early years, while the WHO/ISUP grade was preferred in recent years. Third, the differences in background characteristics such as age, sex, smoking status, and comorbidities between the groups may confound the causal relationship between obesity and pathological features to some extent. Last, some noteworthy pathological variables, such as sarcomatoid differentiation, tumor necrosis, and pathological nodal stage, were not included in our analysis for various reasons, potentially limiting our conclusions.

Conclusions

Our study found that obesity was associated with less aggressive pathological features in a large cohort of patients with ccRCC, such as low tumor nuclear grade, low rate of renal capsular invasion, perirenal fat or renal sinus fat invasion, and vein cancerous embolus. This finding may provide clinicopathological evidence and explanations for the “obesity paradox” of RCC.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Young, M. et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00917-6 (2024).

Tan, S. K., Hougen, H. Y., Merchan, J. R., Gonzalgo, M. L. & Welford, S. M. Fatty acid metabolism reprogramming in ccRCC: Mechanisms and potential targets. Nat. Rev. Urol. 20, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-022-00654-6 (2023).

Schulze, M. B. & Stefan, N. Metabolically healthy obesity: From epidemiology and mechanisms to clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-024-01008-5 (2024).

Renehan, A. G., Tyson, M., Egger, M., Heller, R. F. & Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371, 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X (2008).

Graff, R. E. et al. Obesity in relation to renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival in three prospective studies. Eur. Urol. 82, 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2022.04.032 (2022).

Venkatesh, N., Martini, A., McQuade, J. L., Msaouel, P. & Hahn, A. W. Obesity and renal cell carcinoma: Biological mechanisms and perspectives. Semin. Cancer Biol. 94, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.06.001 (2023).

Johansson, M. et al. The influence of obesity-related factors in the etiology of renal cell carcinoma-A mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 16, e1002724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002724 (2019).

Capitanio, U. et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 75, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.036 (2019).

Nam, G. E. et al. Obesity, abdominal obesity and subsequent risk of kidney cancer: A cohort study of 23.3 million East asians. Br. J. Cancer. 121, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0500-z (2019).

Turco, F. et al. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC): Fatter is better? A review on the role of obesity in RCC. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 28, R207–R216. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-20-0457 (2021).

Petrelli, F. et al. Association of obesity with survival outcomes in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e213520. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3520 (2021).

Ringel, A. E. et al. Obesity shapes metabolism in the tumor microenvironment to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Cell 183 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.009 (2020).

Bader, J. E. et al. Obesity induces PD-1 on macrophages to suppress anti-tumour immunity. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07529-3 (2024).

Gati, A. et al. Obesity and renal cancer: Role of adipokines in the tumor-immune system conflict. Oncoimmunology 3, e27810. https://doi.org/10.4161/onci.27810 (2014).

Sanchez, A. et al. Transcriptomic signatures related to the obesity paradox in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30797-1 (2020).

Parker, A. S. et al. Greater body mass index is associated with better pathologic features and improved outcome among patients treated surgically for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology 68, 741–746 (2006).

Tsivian, E. et al. Body mass index and the clinicopathological characteristics of clinically localized renal masses: An international retrospective review. Urol. Oncol. 35 459.e451–459.e455 (2017).

Jeon, H. G. et al. Prognostic value of body mass index in Korean patients with renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 183, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.004 (2010).

Chen, K. et al. Prevalence of obesity and associated complications in China: A cross-sectional, real-world study in 15.8 million adults. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 25, 3390–3399. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15238 (2023).

Pan, X. F., Wang, L. & Pan, A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9, 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00045-0 (2021).

Lee, W. K. et al. Prognostic value of body Mass Index according to histologic subtype in nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma: A large cohort analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 13, 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2015.04.012 (2015).

Shuch, B. et al. Understanding pathologic variants of renal cell carcinoma: distilling therapeutic opportunities from biologic complexity. Eur. Urol. 67, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.04.029 (2015).

Peired, A. J. et al. Sex and gender differences in kidney cancer: Clinical and experimental evidence. Cancers (Basel). 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184588 (2021).

Sun, L. et al. Impact of Estrogen on the relationship between obesity and renal cell carcinoma risk in women. EBioMedicine 34, 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.07.010 (2018).

Choi, Y. et al. Body mass index and survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: A clinical-based cohort and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer. 132, 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27639 (2013).

Seon, D. Y., Kwak, C., Kim, H. H., Ku, J. H. & Kim, H. S. Prognostic implication of body Mass Index on Survival outcomes in surgically treated nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma: A single-institutional retrospective analysis of a large cohort. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 27, 2459–2467. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08417-6 (2020).

Cho, H. J. et al. Prognostic value of capsular invasion for localized clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 56, 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2008.11.031 (2009).

Ha, U. S. et al. Renal capsular invasion is a prognostic biomarker in localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 8, 202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18466-9 (2018).

Bertini, R. et al. Impact of venous tumour thrombus consistency (solid vs friable) on cancer-specific survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 60, 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.029 (2011).

Bertini, R. et al. Renal sinus fat invasion in pT3a clear cell renal cell carcinoma affects outcomes of patients without nodal involvement or distant metastases. J. Urol. 181, 2027–2032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.048 (2009).

Wagner, B. et al. Prognostic value of renal vein and inferior vena cava involvement in renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 55, 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.053 (2009).

Kresowik, T. P., Johnson, M. T. & Joudi, F. N. Combined renal sinus fat and perinephric fat renal cell carcinoma invasion has a worse prognosis than either alone. J. Urol. 184, 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.010 (2010).

Ong, C. S. H. et al. The impact of body mass index on oncological and surgical outcomes of patients undergoing nephrectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 132, 608–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.16103 (2023).

Albiges, L. et al. Body Mass Index and metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Clinical and biological correlations. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 34, 3655–3663. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7311 (2016).

Ji, J., Yao, Y., Guan, F., Luo, L. & Zhang, G. Impact of BMI on the survival of renal cell carcinoma patients treated with targeted therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Cancer. 75, 1768–1782. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2023.2237220 (2023).

Donin, N. M. et al. Body mass index and survival in a prospective randomized trial of localized high-risk renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 25, 1326–1332. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0226 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82372883 to Linhui Wang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: Fu Z., Wu Z., Wang L. Acquisition of data: Fu Z., Bao Y., Dong K., Gu D., Wang Z., Ding J., He Z., Gan X., Wu Z., Yang C.Analysis and interpretation of data: Fu Z., Bao Y., Dong K., Gu D. Drafting of the manuscript: Fu Z. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Yang C., Wu Z., Wang L. Statistical analysis: Fu Z., Bao Y., Dong K., Gu D. Supervision: Wang L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Z., Bao, Y., Dong, K. et al. Association of body mass index with clinicopathological features among patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with surgery: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84684-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84684-7