Abstract

Oral Cancer screening through the detection of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders (OPMDs) reduces Oral Cancer mortality and the overall burden of Oral Cancer. However, the high cost and the low accessibility are the major barriers associated with Oral Cancer screening. The present study aims to optimize the screening and early diagnosis of Oral Cancer through the capacity building of Community Health Officers (CHOs) posted in Ayushman Arogya Mandir (erstwhile Health and Wellness Centers) in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. A quasi-experimental interventional study was conducted among CHOs of the Jodhpur district of Rajasthan, India. A total of 46 CHOs underwent one day of training on Oral Cancer screening through Oral Visual Examination (OVE). CHOs’ knowledge was assessed pre-training, post-training, and at a two-month follow-up. CHOs conducted screenings over eight months, and ENT specialists remotely validated their findings. This study evaluated the effectiveness of training CHOs in Oral Cancer screening and assessed their screening performance and diagnostic accuracy. The training on Oral Cancer screening resulted in significant and sustained knowledge gains among CHOs. CHOs with higher educational qualifications, previous job experience, and previous knowledge of Oral Cancer screening performed significantly better than others. The overall sensitivity and specificity of CHO screenings were 83.87% and 98.31%, respectively, with an overall diagnostic accuracy of 96.17%. Training CHOs in Oral Cancer screening significantly improved their knowledge and screening performance. CHO findings showed high diagnostic accuracy. The results of the study support the potential role of trained CHOs in community-based Oral Cancer screening programs. This can be a sustainable and effective implementation strategy to enhance Oral Cancer screening in resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral Cancer ranks second among the most common cancers in India, with an incidence rate of 10.4% and a mortality rate of 9.3%1. The associated risk factors of Oral Cancer are tobacco use (including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and chewing betel nut), chronic alcoholism, and the human papillomavirus (HPV)2,3. Tobacco consumption and alcohol usage are the most prevalent risk factors associated with Oral Cancer4,5.

Jodhpur is the second most populated district in Rajasthan, India, with a population of approximately 3.7 million6. While district or region-specific cancer registry data are limited, the prevalence of Head &Neck and Oral Cancer was reported to be 32.18% in Rajasthan, India7. As per National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) data of Rajasthan, India, 42% of men and 6.9% of women aged 15 years and above consume tobacco in any form8. In the Jodhpur district of Rajasthan, 43.6% of men and 6.9% of women aged 15 years and above consume tobacco in any form9. In Rajasthan, the most commonly consumed forms of tobacco include khaini, zarda, pan masala, mishri, bidi, gudakhu, cigarettes, chillum, and hookah10,11. According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2016–17, in Rajasthan, 22.0% of men, 5.8% of women, and 14.1% of all adults consume smokeless tobacco8.

As part of India’s flagship Ayushman Bharat initiative, the Government of India launched Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) to deliver Comprehensive Primary Health Care (CPHC) services, including preventive, promotive, and screening services for Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs). Screening and prevention of NCDs, including Oral Cancer, are among the twelve CPHC services of the Ayushman Bharat - Health and Wellness Centres (AB-HWCs) initiative12. These Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) have been recently renamed as Ayushman Arogya Mandirs, reflecting their expanded role in accessible community-based healthcare. Community Health Officers (CHOs) operate these centres and are instrumental in delivering front-line services, including oral cancer screening.

CHOs act as the link between the community and the healthcare system in providing twelve CPHC services, including preventive, curative, promotive, palliative, and rehabilitative care13. In India, CHOs are generally trained nurses or Ayurveda practitioners who undergo a six-month certificate programme in community health before being posted at Ayushman Arogya Mandir (erstwhile Health and Wellness Centers)12,14. CHOs have an educational background in nursing (BSc Nursing or GNM) or Ayurvedic medicine (BAMS)14. Their role is central to achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in India by bringing quality healthcare closer to rural and underserved populations12,14. Community Health Officers (CHOs) at Ayushman Arogya Mandir are supposed to contribute to Oral Cancer screening12,13. However, the lack of trained healthcare professionals and the lack of awareness in the community about the significance of oral health and Oral Cancer screening are the major causes of low Oral Cancer screening in India15,16.

In one randomized clinical trial in Kerela, India, Oral Cancer screening through the detection of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders (OPMDs) by Oral Visual Examination (OVE) resulted in a 34% reduction in Oral Cancer mortality17. OVE involves the examination of the oral cavity for the presence of most common OPMDs like Leukoplakia, Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF), and Erythroplakia18. Oral Cancer Screening through the identification of OPMDs has benefits but also barriers, like its associated costs and barriers to accessibility, even in the most advanced healthcare systems19. Previous studies from India and Sri Lanka have shown the successful utilization of trained Community Health Workers in Oral Cancer screening17,20,21,22,23,24. The lower cost, ease of accessibility, and the scalable option of Community Health Workers in Oral cancer screening may be a sustainable strategy for screening and detecting Oral Cancer in developing countries like India.

The present study aims to optimize the screening and early diagnosis of Oral Cancer through the capacity building of Community Health Officers (CHOs) posted in Ayushman Arogya Mandir in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan, India. The training and workshop on Oral Cancer screening covering Oral Visual Examination (OVE) was provided to CHOs. The effectiveness of the training was evaluated through pre-, post-, and follow-up assessments of CHOs. The study also evaluated the association of screening performance of CHOs with their sociodemographic characteristics. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of CHO findings were determined.

Methods

Study design and settings

A quasi-experimental interventional study was conducted among Community Health Officers (CHOs) posted in Ayushman Arogya Mandir in the Jodhpur district of Rajasthan, India. The fifty CHOs posted at Ayushman Arogya Mandir in six different blocks (Balesar, Baori, Bilara, Bhopalgarh, Luni, and Mandore) of the Jodhpur district were nominated randomly for the study by the Chief Medical Health Officer (CMHO) of Jodhpur. In India, CMHOs supervise and coordinate medical activities at the district level. CHOs were selected using a convenience sampling method.

Study participants

Out of 50 nominated CHOs, 46 CHOs attended the training and participated in the study. Trained CHOs conducted opportunistic oral cancer screening at their respective Ayushman Arogya Mandirs. As this was an opportunistic screening conducted at Ayushman Arogya Mandirs, individuals were screened during their routine visits to the health centres. Community mobilization and routine outreach activities were used to raise awareness and encourage participation. The informal verbal communication regarding Oral cancer screening service was made by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and CHOs during their routine house-to-house visits. Individuals who visited the Ayushman Arogya Mandir for any reason and met the inclusion criteria, such as being above 30 years or between 18 and 30 years with tobacco and/or alcohol consumption habits, were invited to participate and enrolled after providing written informed consent. CHOs conducted Oral cancer screening at their respective Ayushman Arogya Mandir for eight months (May 2023- December 2023). Forty-six trained CHOs screened a total of 209 participants at their respective Ayushman Arogya Mandir.

Training intervention

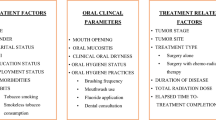

CHOs received a comprehensive training program on oral cancer screening conducted by a team of ENT and pathologists. One day of training and a workshop on Oral cancer screening by Oral Visual Examination (OVE) was given to CHOs at ICMR-NIIRNCD, Jodhpur. The training included theoretical and practical components, covering identifying OPMDs, oral visual examination techniques, informed consent procedures, and the use of mobile phones for clinical photography. The program included a hands-on practice session. The practical sessions focused on performing oral visual examinations (OVE), capturing high-quality intraoral cavity photographs using mobile phones, and using standard data collection formats. An oral cancer screening tool kit (tongue depressor, disposable mask and gloves, flashlight, hand sanitizers, wooden spatula, and red medical waste bag) was given to all CHOs. For conducting oral visual examination, CHOs were instructed to ask participants to rinse their mouths with water and remove any dentures, if present. CHOs were trained to conduct a thorough bilateral examination of the oral cavity and capture photographs of the oral mucosa with their mobile phones. CHOs were trained to take clear, well-lit images, minimizing reflections and obstructions. Any suspected OPMDs were documented, and the photographs of all screened participants were then forwarded to ENT specialists for remote validation.

An online group was created to provide technical support and resolve CHO queries. The monitoring visit was done at the respective Ayushman Arogya Mandir every three months to resolve their queries and replenish the oral cancer screening kit. The knowledge assessment test was conducted at three time points: before the training (pre-training), immediately after the training (post-training), and during a follow-up assessment after two months of training.

Data collection

Following the training, CHOs were assigned to conduct Oral cancer screening at their respective Ayushman Arogya Mandir for eight months (May 2023- December 2023). Forty-six trained CHOs screened a total of 209 participants. CHOs did OVE on the screened participants and documented the OPMD type, if any, which was later validated by an ENT specialist. The second-level validation of suspected OPMDs was conducted remotely by an ENT specialist. Oral cavity photographs taken by CHOs during the screening were reviewed by an ENT specialist, enabling expert evaluation without requiring participants to attend an in-person follow-up visit. The photographs of all the screened 209 participants were validated by ENT remotely.

Data variables

CHOs’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, residence, marital status, place of posting, highest educational qualification, previous work experience, work experience as CHO, and previous knowledge of oral cancer screening, were collected at the time of training. These variables were used to find the association with the Oral cancer screening performance.

Statistical analysis

SPSS Version 28.0 was used for data analysis. One-way repeated measures ANOVA was done to compare pre-training, post-training, and follow-up knowledge scores. The independent samples t-test was employed to assess differences in the mean number of screened participants by CHO based on their sociodemographic variables. P-values < 0.001 and P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive prediction value, Negative prediction value, Positive likelihood ratio, Negative likelihood ratio, and overall diagnostic accuracy with 95% CI were determined.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute for Implementation Research on Non-Communicable Diseases (ICMR-NIIRNCD), Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. The approval number is IEC-NIIRNCD/2022/FR/002. The present study methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was taken from the study participants. No incentives were given to CHOs to conduct the oral cancer screening. There was no provision of incentive for the screened participants. Following Wilson and Junger screening guidelines25, the OPMD-suspected participants were referred to the tertiary health care centers where further clinical evaluation, including biopsy and treatment, could be undertaken.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of CHOs

Out of 50 nominated CHOs, 46 (92%) CHOs attended the training program and participated in the study. Table 1 represents the sociodemographic characteristics of the CHOs who participated in the study. The mean age of the study participants was 30.29 ± 3.97 years (Range: 24.6–43.6). Most of the participants were married (78.3%) and held a General Nursing Midwifery (GNM) educational qualification (67.4%). Only 15.2% resided in the same area as their posting. The mean work experience as CHO was 13.04 ± 2.55 months (Range: 11–23 months). Only 14 (30.4%) of CHOs have prior work experience. Although 93.5% had prior knowledge of Oral Cancer screening, only 2.2% had received training on Oral Cancer screening before this study.

Pre and post-training assessment

One-day training and workshop on Oral Cancer screening covering the theoretical and practical aspects of OVE was provided to CHOs. The impact of the training intervention on CHOs’ knowledge of Oral Cancer screening was assessed through pre-training, post-training, and follow-up evaluation. Table 2 shows the scores/marks obtained by CHO before and after the training intervention, out of a maximum of 10 marks. The mean marks before training were 5.93 ± 1.84. The mean marks immediately after the training were improved to 9.46 ± 0.83. After 2 months of follow-up, the mean marks retained to 7.6 ± 1.16. Figure 1 represents the box plot showing the comparison of CHOs’ scores on Oral Cancer screening pre-and post-training. One-way repeated measures ANOVA shows a significant difference (P < 0.001) in post-training and follow-up scores compared to pre-training scores.

Association of oral cancer screening performance of CHO with their sociodemographic characteristics

Oral Cancer Screening performance, defined as the number of participants screened, varied with CHO sociodemographic characteristics, as shown in Table 3. The independent samples t-test was employed to assess differences in the mean number of screened participants by CHO based on their sociodemographic variables. CHOs with a B.Sc. in Nursing (7.8 ± 10.3) educational qualification screened more participants than those with GNM qualifications (2.9 ± 4.0) (P < 0.05). CHOs with more than one year of previous work experience before joining as CHO had higher screening performance (with the highest screening count observed in those with > 6 years of experience, 12.6 ± 15.6) compared to those with less than one year of experience (2.9 ± 4.1). The statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the screening performance of CHOs with more than six years of experience compared to those with less than one year of experience was determined through independent samples t-test. Furthermore, CHOs with prior knowledge of oral cancer screening reported screening an average of 4.9 ± 7.1 participants, while those without any prior knowledge did not screen any participant (P < 0.001).

Diagnostic accuracy of CHO findings compared to ENT validation

Table 4 compares CHO findings with ENT validation for detecting OPMDs. CHOs screened a total of 209 participants, and all were subsequently validated by an ENT specialist remotely. Among those referred to as suspected OPMDs by CHO, three were later confirmed by ENT to have no visible mucosal lesions and were thus considered false positives. Additionally, five cases initially classified as OPMD negative by CHOs were later identified as having OPMDs during expert review by ENT, representing false negatives. The expert validation also confirmed 26 true positive and 175 true negative cases.

As shown in Table 4, the overall sensitivity of CHO findings was 83.87% (95% CI: 70.92 − 96.81%), and the specificity was 98.31% (95% CI: 96.42 − 100%). The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were 89.66% (95% CI: 78.57 – 100%) and 97.22% (95% CI: 94.82 – 99.62%) respectively. The positive likelihood ratio was 49.76, while the negative likelihood ratio was 0.16. The overall diagnostic accuracy of CHO findings in detecting OPMD was 96.17% (95% CI: 93.57-98.77%).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that our structured training intervention significantly improved the knowledge and screening performance of Community Health Officers (CHOs) in detecting Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders (OPMDs). According to National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) data, 1.2% of men and 0.9% of women have ever undergone oral cancer screening in India8. In Jodhpur, the oral cancer screening rate is only 0.3%9. The present study aimed to optimize the Oral Cancer screening rate by capacity building of CHOs. According to the Wilson and Jungner criteria for screening, a screening program should not only detect disease early but also ensure that diagnostic confirmation and treatment facilities are accessible25. In our study, participants with suspected OPMDs were referred to tertiary health care centres where further clinical evaluation, including biopsy and further treatment, could be undertaken.

The significant improvement in CHOs’ knowledge following training (mean scores: 5.93 ± 1.84 pre-training to 9.46 ± 0.83 post-training, P < 0.001) suggests that even a short, well-structured training module can effectively enhance screening competencies. While follow-up scores showed a slight decline (7.60 ± 1.16), they remained significantly higher than pre-training levels, indicating knowledge retention over time. Similar studies from India, Sri Lanka, and Florida, USA, have reported that community health workers can be effectively trained for non-specialist cancer screening roles, leading to improved detection rates and community engagement in early diagnosis efforts17,20,21,26.

The variation in screening performance based on CHOs’ sociodemographic characteristics is an important finding. CHOs with a B.Sc. in Nursing screened more participants than those with GNM qualifications (P < 0.05), suggesting that higher educational qualifications may enhance screening performance. Additionally, prior work experience and oral cancer screening knowledge were associated with better oral cancer screening performance. The study results align with the previous studies from India and Brazil, where previous work experience, educational qualifications, and training directly impact the competency of community healthcare workers20,27.

Our study demonstrated that oral cancer screening conducted by trained Community Health Officers (CHOs) using oral visual examination (OVE) achieved a sensitivity of 83.87% and a specificity of 98.31%. These findings are comparable to those of Birur, N. P. et al.21, where trained community health workers screened individuals through mobile phone-based photography of the oral cavity, and the images were remotely assessed by oral medicine specialists. Previous studies have reported sensitivity ranging from 59 to 96.6% and specificity between 98.6% and 99.3% for similar screening approaches20,28,29. We observed that the overall diagnostic accuracy of CHO in identifying OPMD was 96.17%, which aligns closely with findings from Birur, N. P. et al.21 (96.4%) and Thampi, V. et al.20 (98.29%).

The study findings highlight the feasibility of utilizing CHOs for oral cancer screening in primary healthcare settings, which could bridge the existing gap in early detection and reduce oral cancer mortality in resource-limited regions like India.

Study limitations

As the study was conducted in only one district of Rajasthan, the study results limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions and settings. However, the results are applicable in similar resource-limited settings. In the present study, trained CHOs conducted opportunistic oral cancer screening at their respective Ayushman Arogya Mandirs. Although community mobilization and routine outreach activities were used to raise awareness and encourage participation, the compliance rate for the initial screening was not systematically documented across all Ayushman Arogya Mandir. Additionally, the number of participants confirmed to have oral Cancer following referral was not documented since the study did not include active follow-up after referral for biopsy at tertiary health care facilities. While the study results demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of CHOs in Oral Cancer screening, future research is required to assess CHO competency in the timely referral of patients for further confirmation and treatment of Oral Cancer.

Conclusion and recommendations

The training on Oral Cancer screening resulted in significant and sustained knowledge gains among CHOs. The overall sensitivity and specificity of CHO screenings were 83.87% and 98.31%, respectively, with an overall diagnostic accuracy of 96.17%. The study results support Community Health Officers’ potential role in community-based Oral Cancer screening programs. Integrating CHOs in community-based Oral Cancer screening can be a sustainable and effective implementation strategy to enhance Oral Cancer screening in resource-limited settings.

Data availability

The study data is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Coletta, R. D., Yeudall, W. A. & Salo, T. Current trends on prevalence, risk factors and prevention of oral Cancer. Front. Oral Health. 5, 1505833. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2024.1505833 (2024).

Thakral, A. et al. Smoking and alcohol by HPV status in head and neck cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. Nat. Commun. 15, 7835. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51679-x (2024).

Jun, S. et al. The combined effects of alcohol consumption and smoking on Cancer risk by exposure level: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 39, e185. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e185 (2024).

Eloranta, R. et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: effect of tobacco and alcohol on cancer ___location. Tob. Induc. Dis. 22. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/189303 (2024).

District Census Handbook 2011- Jodhpur, Census of India.

Aggarwal, V. P., Rao, D. C. L., Mathur, A., Batra, M. & Makkar, D. K. Prevalence of head and neck and oral Cancer in Rajasthan: an infirmary based retrospective study. Clin. Cancer Invest. J. 4, 339–343 (2015).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India (2021).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5, State and District Factsheets (IIPS, 2021).

Gupta, A. et al. Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of tobacco consumption among adolescents: an observational study from a rural area of Rajasthan. Indian J. Community Med. 48, 748–754. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_382_23 (2023).

11 Gupta, P. C. & Ray, C. S. Smokeless tobacco and health in India and South Asia. Respirology 8, 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00507.x (2003).

Tripathi, N. et al. Performance of health and wellness centre in providing primary care services in Chhattisgarh, India. BMC Prim. Care. 25, 360. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02603-1 (2024).

Kotwani, P., Pandya, A. & Saha, S. Community health officers: key players in the delivery of comprehensive primary healthcare under the Ayushman Bharat programme. Curr. Sci. 120, 607–608 (2021).

Ayushman Bharat Comprehensive Primary. Health Care Through Health. And Wellness Centres: Operational Guidelines.

Gambhir, R. S. & Gupta, T. Need for oral health policy in India. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 6, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.4103/2141-9248.180274 (2016).

Kakatkar, G. et al. Barriers to the utilization of dental services in Udaipur, India. J. Dent. (Tehran). 8, 81–89 (2011).

Sankaranarayanan, R. et al. Effect of screening on oral cancer mortality in Kerala, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365, 1927–1933. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66658-5 (2005).

Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A comprehensive review on clinical aspects and management. Oral Oncol. 102, 104550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104550 (2020).

D’Cruz, A. K. & Vaish, R. Risk-based oral cancer screening - lessons to be learnt. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 471–472. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00511-2 (2021).

Thampi, V. et al. Feasibility of training community health workers in the detection of oral Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2144022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44022 (2022).

Birur, N. P. et al. Role of community health worker in a mobile health program for early detection of oral Cancer. Indian J. Cancer. 56, 107–113. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijc.IJC_232_18 (2019).

Warnakulasuriya, K. A. & Nanayakkara, B. G. Reproducibility of an oral cancer and precancer detection program using a primary health care model in Sri Lanka. Cancer Detect. Prev. 15, 331–334 (1991).

Warnakulasuriya, K. A. et al. Utilization of primary health care workers for early detection of oral Cancer and precancer cases in Sri Lanka. Bull. World Health Organ. 62, 243–250 (1984).

Mathew, B., Sankaranarayanan, R., Wesley, R., Joseph, A. & Nair, M. K. Evaluation of utilisation of health workers for secondary prevention of oral Cancer in Kerala, India. Eur. J. Cancer B Oral Oncol. 31B, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0964-1955(95)00016-b (1995).

Wilson, J. M. G. & Jungner, G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease (World Health Organization, 1968).

27 Rodriguez, N. M. et al. Community-based participatory design of a community health worker breast cancer training intervention for South Florida Latinx farmworkers. PLoS One 15, e0240827. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240827 (2020).

Kienen, N. et al. Cervical Cancer screening among underscreened and unscreened Brazilian women: training community health workers to be agents of change. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 12, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2018.0026 (2018).

Mathew, B. et al. Reproducibility and validity of oral visual inspection by trained health workers in the detection of oral precancer and Cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 76, 390–394. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1997.396 (1997).

Mehta, F. S. et al. Detection of oral Cancer using basic health workers in an area of high oral cancer incidence in India. Cancer Detect. Prev. 9, 219–225 (1986).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to CMHO, Jodhpur, Rajasthan for nominating CHOs for this study. We appreciate the efforts of all the nominated CHOs. We acknowledge the efforts of Mr. Dinesh Kumar in formatting and language editing the manuscript. Special thanks to Prof. Arun Kumar Sharma for his invaluable support in the development of the study. Our sincere gratitude to ICMR-NIIRNCD for funding and supporting the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JKG wrote the manuscript and prepared all the manuscript tables. P.K.A. helped in the preparation of Table No. 4 and reviewed the manuscript. BVB reviewed the manuscript thoroughly and helped finalize it. JKG communicated the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gautam, J.K., Anand, P.K., Chouhan, M. et al. Capacity building of community health officers for optimizing the screening and early diagnosis of oral cancer in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Sci Rep 15, 16027 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00225-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00225-w