Abstract

The rapid progress of the Internet has significantly boosted information exchange and aggregation. However, it has also heightened concerns regarding privacy issues such as personal data leakage and misuse. Previous studies have examined how demographic variables and personality traits affect Internet privacy concerns. Nevertheless, these factors are multi-dimensional and complex. Interpersonal factors and psychological characteristics such as social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy also deserve consideration. A structured questionnaire was utilized to survey 824 Chinese university students. Structural equation modeling was employed to explore the mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy-preserving self-efficacy in the relationship between personality traits and privacy concerns. Conscientiousness, privacy-preserving self-efficacy, and social anxiety positively forecast Internet privacy concerns among university students. Extroversion, agreeableness, and openness have significant negative impacts on privacy concerns. Social anxiety and privacy-preserving self-efficacy act as chain mediators in the relationship between agreeableness and privacy concerns, as well as between conscientiousness and privacy concerns. The findings offer new perspectives on the underlying mechanisms of Internet privacy issues and emphasize how offline activities influence Internet behavior. A comprehensive and multifaceted approach is required to address Internet privacy concerns among university students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internet privacy concerns are commonly understood as an individual’s overall perception of privacy risks within the online environment1. Early research on this topic can be traced back to the 1990s, when Smith et al.2. introduced a conceptual model for understanding information privacy concerns, focusing on examining the impact of consumer privacy concerns on the structure of the consumer market. Their work also explored how users perceive and protect network privacy and security. The model offered a theoretical framework distinct from traditional market contexts3. Over time, Internet privacy concerns have become an increasing interdisciplinary research focus4, gaining relevance in today’s digitally interconnected world. Especially in today’s networked society where individuals are consistently communicating, concerns surrounding Internet privacy are particularly important.

Studies have shown that Internet privacy concerns are closely tied to individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, emotional states, and interpersonal relationships regarding privacy5,6.Personality traits, defined as relatively stable psychological tendencies and behavioral patterns, significantly influence how individuals perceive and manage Internet privacy7, with different personality traits leading to varying degrees of concern regarding Internet privacy8. For instance, Bansal et al.’s study on online health information privacy found that emotional instability and agreeableness can increase sensitivity to privacy concerns. However, there has been limited research regarding how personality traits affect Internet privacy concerns specifically among Chinese university students. Yet, it is important to examine this population, given their extensive use of the Internet, lack of social experience, and susceptibility to external influences, all of which make them especially vulnerable to privacy issues.

Philosopher Schoeman (1984) emphasized that privacy plays a crucial role in facilitating interpersonal relationships, with communication being a fundamental component of human social behavior9. Under some circumstances, revealing personal information can reduce privacy concerns by fostering social utility and closeness between individuals10,11. Moreover, research has found that Internet privacy concerns are related to social anxiety. Adolescents with higher levels of social anxiety are more likely to worry about potential privacy risks12. People with social anxiety often think of themselves negatively, which correlates with lower self-efficacy in privacy protection13. There is also a negative correlation with self-efficacy14.

Privacy protection self-efficacy reflects individuals’ confidence in their ability to safeguard their privacy, with those possessing low self-efficacy being more vulnerable to privacy risks15. Research suggests that privacy protection self-efficacy is a key factor in shaping Internet privacy concerns16. Along with social anxiety, it can jointly influence risky Internet behaviors17. Research suggests that privacy protection self-efficacy affects Internet privacy concerns through a mediating effect18.Individuals with social anxiety are more likely to worry about their performance in interpersonal communication and social activities due to negative social experiences, which can undermine their confidence and ability to address privacy concerns. Given the relationship between social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy, it is evident that both factors should be considered together for their mediating roles, with the potential for a chain mediation effect.

The following research hypotheses are proposed:

-

(1)

Social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy have chain mediating effects on the influence of conscientiousness on Internet privacy concerns.

-

(2)

Social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy have chain mediating effects on the influence of extroversion on Internet privacy concerns.

-

(3)

Social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy play chain mediating roles in the influence of agreeableness on Internet privacy concerns.

-

(4)

Social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy play chain mediating roles in the influence of openness on Internet privacy concerns.

-

(5)

Social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy play chain mediating roles in the influence of neuroticism on Internet privacy concerns.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study involved university students from several institutions located in Shaanxi and Fujian provinces, China. The survey was administered online via the Questionnaire Star platform, with teachers assisting by distributing electronic links to their respective students. Participation was voluntary, and students completed the survey anonymously using either mobile phones or computers. The survey required full completion, and questions could be skipped. Of the 1000 questionnaires distributed, 931 were returned, yielding a response rate of 93.10%. After removing invalid responses—such as incomplete or erroneous answers—824 valid questionnaires were retained, resulting in an effective response rate of 88.50%. The sample consisted of 305 males (37.01%) and 519 females (62.98%), with an average age of 20.28 ± 1.47 years. The participants included 240 freshmen (29.12%), 185 sophomores (22.45%), 224 juniors (27.18%), and 175 seniors (21.23%). A majority of the participants were Han Chinese (813 individuals, 98.66%), with 11 participants from ethnic minority groups (1.33%). Participants were compensated with extra class points and small gifts upon completing the survey.

Measures

Internet privacy concern scale for university students

The Internet Privacy Concern scale, developed by Cong Beile et al.19, measures university students’ concerns about Internet privacy across four dimensions: risk assessment, security intentions and behavior, emotional experience, and cultural values. The scale consists of 16 items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s α for the scale in this study was 0.89, indicating high internal consistency.

Brief version of China’s big five personality questionnaire (CBF-PI-B)

The brief version of China’s Big Five Personality questionnaire (CBF-PI-B), revised by Wang Mengcheng et al.20, assesses personality traits in five key areas: agreeableness, extroversion, neuroticism, openness, and conscientiousness. Each dimension includes 8 items, with 7 reverse-scored items and 33 forward-scored items, totaling 40 items. Responses are rated on a 6-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates “completely inconsistent” and 6 indicates “completely consistent”. Higher scores reflect stronger personality traits in the respective dimensions. The scale’s Cronbach’s α values were 0.78 for agreeableness, 0.81 for openness, 0.86 for neuroticism, 0.78 for extroversion, and 0.86 for conscientiousness.

Privacy protection Self-Efficacy scale

The Privacy Protection Self-Efficacy scale, originally developed by Thatcher et al.21and translated into Chinese by Xu Yiming et al.22, assesses individuals’ privacy protection self-efficacy enacted by the individual (3 items) and by external forces (4 items). Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “completely disagree” and 7 representing “completely agree”. The total score is calculated by summing the item scores. Cronbach’s α was 0.92 for internal privacy protection self-efficacy and 0.79 for external privacy protection self-efficacy.

Social anxiety scale

The Social Anxiety scale, developed by Fenigstein et al.and revised by Xiangdong Wang et al.23, measures individuals’ subjective social anxiety levels in social interactions. The scale consists of 6 items, with 5 positive-scoring items and 1 reverse-scoring item. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate greater levels of social anxiety. Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.72, reflecting acceptable internal consistency.

Data processing

SPSS24.0 was used for descriptive statistical analysis and hierarchical regression analysis, and Mplus7.0 software was employed to construct the structural equation model for assessing the relationships between the main variables.

Results

Common method Bias test

Given that the data for this study was collected using self-reported questionnaires, there is a potential risk of common method bias. To mitigate this, we employed several strategies during data collection, such as incorporating verification and reverse-coded questions, ensuring participant anonymity, and balancing the items in the questionnaire24. To test for common method bias, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test25. The results indicated that 9 eigenvalues exceeded 1, with the first factor accounting for 18.68% of the variance, well below the critical threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias is not a significant issue in this dataset.

Correlation analysis of variables

The analysis results in Table 1 show correlations among the five personality variables, except neuroticism. These personality variables (except neuroticism) are correlated with Internet privacy concerns, social anxiety, and privacy protection self-efficacy to varying degrees.

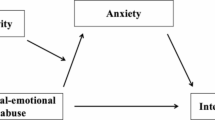

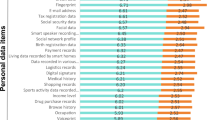

The effects of agreeableness on Internet privacy concerns: The chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy-preserving self-efficacy

Latent variable structural equation modeling was used to validate the chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy-protection self-efficacy in the influence of agreeableness on internet privacy concerns. Demographic variables such as age and grade were controlled. The model included agreeableness as the exogenous latent variable, social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy as the mediating latent variables, and Internet privacy concerns as the endogenous latent variable. The model was analyzed using the maximum likelihood method. The model fit indices were: χ2 = 187.33, df = 48, χ2/df = 3.90, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05, indicating an acceptable fit.

The path coefficients in Fig. 1 indicate that agreeableness has a significant negative effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = -0.12, p < 0.05) and a significant positive effect on self-efficacy for privacy protection (β = 0.15, p < 0.001). Moreover, agreeableness appears to exert a significant negative effect on social anxiety (β = -0.43, p < 0.001), while social anxiety has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Finally, Fig. 1 reflects the significant negative effect of social anxiety on privacy protection self-efficacy (β= -0.41, p < 0.001) and a significant positive privacy-preserving self-efficacy effect (β = 0.42, p < 0.001).

To further test the significance of the mediating effects, a bias-corrected nonparametric percentile bootstrap method was applied, using 5,000 repeated samples26,27. The results indicate that the 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of privacy-preserving self-efficacy is [-0.14, -0.04], which does not contain 0, indicating a significant mediating effect that accounts for 35% of the total effect. Also, the 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of social anxiety is [-0.20, -0.07], excluding 0 as well, so the mediating effect is notable and accounts for 51% of the total effect. The 95% confidence interval for the mediation effect of privacy protection self-efficacy is [-0.06, -0.02]. As the interval does not contain 0, the mediating effect is also significant and accounts for 14% of the total effect. See Table 2 for details.

he impact of openness on Internet privacy concerns: The chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy

The latent variable structural equation model was used to verify the chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy in the influence of openness on Internet privacy concerns. Controlling demographic variables such as age and grade, a structural equation model was constructed with openness as the exogenous latent variable, social anxiety and privacy self-efficacy as the intermediate latent variables, and Internet privacy concerns as the endogenous latent variable. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the model. The model’s fit indices were χ2 = 187.33, df = 48, χ2/df = 3.80, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05, indicating an acceptable model fit.

As shown in Fig. 2, the path coefficients indicate that openness has a significant negative impact on internet privacy concerns (β = -0.24, p < 0.05) but a significant positive effect on privacy protection self-efficacy (β = 0.42, p < 0.001). Openness has a significant negative effect on social anxiety (β = -0.62, p < 0.001), while the latter has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.22, p < 0.001) and a significant negative effect on privacy self-efficacy (β = -0.19, p < 0.001). Additionally, privacy protection self-efficacy has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.32, p < 0.001).

To further test the significance of the mediating effects, a deviation-corrected non-parametric percentile bootstrap method was applied, using a total of 5000 repeated samples. The findings in Table 3 demonstrate that the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of privacy protection self-efficacy is [-0.22, -0.08], and the interval does not contain 0, so the mediating effect is significant. The 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of social anxiety is [0.08, 0.22], and the interval does not contain 0, so the mediating effect is significant here as well. Furthermore, the 95% confidence interval of the chain mediated effect on self-efficacy of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy is [-0.12, 0.12], and since the interval contains 0, the chain mediated effect is not significant. For details, see Table 3.

The effects of conscientiousness on Internet privacy concerns: The chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy

The latent variable structural equation model was used to verify the chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy self-efficacy in the influence of conscientiousness personality traits on Internet privacy concerns. Similarly, demographic variables such as age and grade were controlled. A structural equation model was designed with conscientiousness as the exogenous latent variable, social anxiety and privacy self-efficacy as the intermediate latent variables, and Internet privacy concerns as the endogenous latent variable. The maximum likelihood method was employed, resulting in the fit indices: χ2 = 143.67, df = 48, χ2/df = 2.99, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.04. The model fit was deemed acceptable.

Figure 3 highlights the significant positive effect of consciousness on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.31, p < 0.001) and social anxiety (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), while reflecting its significant negative effect on privacy protection self-efficacy (β = -0.36, p < 0.001). Social anxiety, in turn, has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) and a significant negative effect on privacy protection self-efficacy (β = -0.30, p < 0.001). Self-efficacy related to privacy protection has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.30, p < 0.001).

In order to further test the significance of the mediating effects, a deviation-corrected non-parametric percentile bootstrap method was used for testing, with a total of 5000 repeated samples. The results show that the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of privacy protection self-efficacy is [0.07, 0.18], and the interval does not include 0, so the mediating effect is significant, accounting for 20% of the total effect. The 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of social anxiety is [0.10, 2.00], and the interval does not contain 0, so the mediating effect is significant, accounting for 29% of the total effect. The 95% confidence interval of the chain mediating effects of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy is [0.36, 1.22]. As the interval does not contain 0 and accounts for 51% of the total effect, the chain mediating effect is significant (Table 4).

The effects of extroversion on Internet privacy concerns: The chain mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy-protecting self-efficacy

The latent variable structural equation model was used to measure the chain mediating effects of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy on the influence of extroversion on Internet privacy concerns. Demographic variables such as age and grade were controlled and a structural equation model was designed as follows: extroversion was used as the exogenous latent variable, social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy were mediating latent variables, and Internet privacy concerns were set as the endogenous latent variable. The model was estimated using the maximum likelihood method, yielding these fit indices: χ2 = 143.67, df = 48, χ2/df = 2.99, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.04. It was determined to be an acceptable fit.

Figure 4 denotes the path coefficients of the model, which show that extroversion has a significant negative impact on Internet privacy concerns (β = -0.36, p < 0.001). Moreover, extroversion positively affects privacy protection self-efficacy to a significant degree (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), while yielding a significant negative effect on social anxiety (β = -0.55, p < 0.001). Social anxiety, on the other hand, has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.20, p < 0.001) and a significant negative effect on privacy protection self-efficacy (β = -0.22, p < 0.001). The latter has a significant positive effect on Internet privacy concerns (β = 0.27, p < 0.001).

A deviation-corrected non-parametric percentile bootstrap method was employed to assess the importance of the mediating effects, with a total of 5000 repeated samples .The results denote that the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of privacy protection self-efficacy is [0.20, 0.07], which does not contain 0, suggesting an important mediating effect. Meanwhile, the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of social anxiety is [0.13, 0.30]. Similarly, the interval does not contain 0, so the mediating effect is significant. The 95% confidence interval of the chain mediating effects of privacy protection self-efficacy and social anxiety is [-0.06, 0.20]. Here, the interval contains 0, so the mediating effect is not significant. For details, see Table 5.

Discussion

This study provides important these findings are true for university students new insights into the complex mediating mechanisms linking the personality traits of university students with their Internet privacy concerns. Notably, previous research has often focused on the direct relationship between agreeableness and Internet privacy concerns without considering the mediating roles of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy. Our findings confirm that agreeableness influences social anxiety, which in turn affects privacy protection self-efficacy and ultimately impacts Internet privacy concerns, supporting hypothesis 3.

Additionally, conscientiousness was found to influence Internet privacy concerns through the chain mediation of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy, supporting hypothesis 1. However, this mediating pathway accounts for only a modest portion of the total effect, suggesting the presence of other potential mediating factors. For example, situational trust has been identified as an important mediator in the relationship between personality traits and privacy concerns28. This result indicates that the mechanisms underlying the relationship between conscientiousness and Internet privacy concerns are complex and warrant further investigation.

Conversely, the chain mediation effects of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy in the relationships between extroversion and Internet privacy concerns, as well as between openness and Internet privacy concerns, were not significant, contradicting hypotheses 2 and 4. This suggests that the relationship between openness, social anxiety, and privacy protection self-efficacy is more nuanced than previously thought. Prior research has suggested that emotional stability may moderate the influence of openness on privacy concerns29. However, they appear to have a relatively minor influence on privacy protection self-efficacy, limiting its mediating role.

The relationship between extroversion and Internet privacy concerns has also been debated in the literature, yielding mixed findings. Some studies suggest that extroversion may reduce privacy concerns in low-sensitivity contexts, while others argue that its influence is diminished in high-sensitivity scenarios30.Our findings further reinforce that the effects of extroversion on privacy concerns vary based on context. Interestingly, we found no correlation between neuroticism and Internet privacy concerns among university students, contradicting hypothesis 5. Previous studies have produced mixed results regarding its influence on privacy concerns, with some suggesting a positive correlation and others reporting a negative association31.These discrepancies highlight the need for more nuanced measurements and methodologies when investigating the role of neuroticism in privacy concerns. It is possible that the unique characteristics of Chinese university students, such as heightened privacy awareness, influenced their responses. Future research should consider exploring the interaction between neuroticism and environmental factors to better understand its impact on privacy concerns.

In sum, while the chain mediation effects of social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy were not significant for openness, extroversion, and neuroticism, these personality traits still directly influenced Internet privacy concerns. This underscores the need for continued research on the role of personality in shaping Internet privacy concerns and the mediating variables that may influence this relationship.

Conclusion

This study explored the influence of personality traits, interpersonal factors, and privacy protection self-efficacy on Internet privacy concerns among Chinese university students. The findings indicate that social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy play a chain mediating role in this relationship. Overall, these results suggest that efforts to enhance privacy protection among university students should focus on both psychological factors and personality traits.

Specifically, the study found that social anxiety and privacy protection self-efficacy significantly mediated the relationship between conscientiousness, agreeableness, and Internet privacy concerns, while the mediation effects for openness, extroversion, and neuroticism were not significant. This highlights the complexity of the relationship between personality traits and privacy concerns and the need for a multifaceted approach to address these issues.

In practice, the findings suggest that universities and educators should prioritize the mental health of students, particularly regarding social anxiety, which can influence privacy-related behaviors. Improving students’ privacy protection self-efficacy, along with fostering traits such as openness and conscientiousness, may help reduce privacy concerns. Future research should continue exploring the nuances of how personality traits interact with psychological factors to influence Internet privacy-related behaviors. The limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which lacks a dynamic, longitudinal view of the changing trends related to college students’ Internet privacy concerns. Future research can adopt a longitudinal approach, using cross-lag analysis and other research methods to explore the development trends and influencing factors of Internet privacy concerns.

The limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which lacks a dynamic, longitudinal view of the changing trends related to university students’ Internet privacy concerns. Future research can adopt a longitudinal approach, using cross-lag analysis and other research methods to explore the development trends and influencing factors of Internet privacy concerns.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the need to protect individual privacy.

References

Zeng, F., Ye, Q., Yang, Z., Li, J., & Song, Y. A. Which privacy policy works, privacy assurance or personalization declaration? An investigation of privacy policies And privacy concerns. J. Bus. Ethics. 176(1), 781–798 (2020).

Smith, H. J., Milberg, S. J., & Burke, S. J. Information privacy: Measuring individuals’ concerns about organizational practices. MIS Q., 167–196. (1996).

Sheehan, K. B., & Hoy, M. G. Dimensions of privacy concern among internet consumers. J. Public. Policy Mark. 19(1), 62–73 (2000).

Wang, Q., Zhang, W., & Wang, H. Privacy concerns toward short-form video platforms: scale development and validation. Front. Psychol. 13(05), 954964–954964 (2022).

Qin, K. (ed Yuan, Q.) The quantitative analysis of doctoral dissertations on internet privacy at home and abroad. Mod. Inform. 38 2 10 (2018).

Wang, L., Li, Q., Qiao, Z., & Liu, S. Impact of protection motivation on privacy concerns and privacy security protection behaviors of SNS. Users J. Intell. 38(10), 7 (2019).

Shen, Q. Internet information privacy concerns and privacy protection behavior of university students in Shanghai. Chin. J. Journalism Commun. 2, 120–129 (2013).

Bansal, G., & Gefen, D. The impact of personal dispositions on information sensitivity, privacy concern and trust in disclosing health information internet. Decis. Support Syst. 49(2), 138–150 (2010).

Schoeman, F. Privacy: philosophical dimensions of the literature (American Philosophical Quarterly, Cambridge University Press, 1984).

Yan, L. Wechat: A new species of media survival. Mod. Commun. 38(2), 4 (2016).

Xiong, H. & Guo, Q. Study on influencing factors of quitting behavior in friends circle. Press. Circles 10, 10 (2019).

Liu, C., Ang, R. P. & Lwin, M. O. Cognitive, personality, and social factors associated with adolescents’ internet personal information disclosure. J. Adolesc. 36(4), 629–638 (2013).

Chen, X. & Wang, Z. Self-Attitudes and intervention of social anxious people. Adv. Psychol. 10(8), 6 (2020).

Fu, M., Ge, M., & Sang, Q. Self-Efficacy and social anxiety of university students. Chin. Mental Health J. 19(7), 2 (2005).

Allen, M. S., Jones, M. V. & Sheffield, D. The influence of positive reflection on attributions, emotions, and self-efficacy. Sport Psychol. 24(2), 211–226 (2010).

Ren, Z., & Jiang, L. The impact of value perception and user participation on the intention of APP continuous use. Enterp. Econ. 4, 91–98 (2020).

Chen, H. T., & Chen, W. Couldn’t or wouldn’t? The influence of privacy concerns and self-efficacy in privacy management on privacy protection. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Social Netw. 18(1), 13–19 (2015).

Chen, H. T. Revisiting the privacy paradox on social media with an extended privacy calculus model: the effect of privacy concerns, privacy self-efficacy, and social capital on privacy management. Am. Behav. Sci. 62(10), 1392–1412 (2018).

Cong, B. Internet Privacy Concerns of University Students: Structure, Influencing Factors, and Roles Unpublished doctoral thesis, Fujian Normal University (2024).

Wang, M., Dai, X., & Yao, S. Development of the Chinese big five personality Inventory(CBF-PI):Psychometric properties of CBF-PI brief version. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 18(5), 545–548 (2011).

Thatcher, J. B., Zimmer, J. C., Gundlach, M. J. & Mcknight, D. H. Internal and external dimensions of computer self-efficacy: an empirical examination. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 55(4), 628–644 (2008).

Xu, Y., Li, H. & Yu, L. Research on the influence of Self-efficacy of privacy protection on privacy behaviors of social network users. Libr. Inform. Service. 63(17), 128–136 (2019).

Wang, X, Wang, X. & Ma, H. Mental Health Rating Scale Manual (updated edition) (Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 1999).

Zhou, H., & Long, L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 6, 942–950 (2004).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(5), 879–903 (2003).

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods. 11(2), 296–325 (2008).

Preacher, K. J. Advances in mediation analysis: a survey and synthesis of new developments [Journal Article; Review]. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 66, 825–852 (2015).

Bansal, G., Zahedi, F. M., & Gefen, D. Do context and personality matter? Trust and privacy concerns in disclosing private information internet. Inf. Manag. 53(1), 1–12 (2016).

Ben-Dyke, A., Cusack, M., Hoare, P., Lycett, M., & Paul, R. J. Information technology. Emerald Manage. Rev. 32(5), 32 (2003).

Schyff, K. V. D., Flowerday, S., & Lowry, P. B. Information privacy behavior in the use of Facebook apps: a personality-based vulnerability assessment. Heliyon 6(8), 1–13 (2020).

Bawack, R. E., Wamba, S. F., & Kevin Daniel André Carillo. Exploring the role of personality, trust, and privacy in customer experience performance during voice shopping: evidence from Sem and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 58(4), 1–42 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the Social Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. FJ2023BF002) awarded to Ziqing Ye.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: BC, ZY, and QJ. Data collection, analysis, and interpretation: YF, ZY and ML. Writing–original draft: TF, QYand BC. Writing– revision and edit: BC, ZY, BL and ZW. All of the authors have approved the publication of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Air Force Military Medical University.The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cong, B., Ye, Z., Jia, Q.n. et al. Personality traits Influence Internet Privacy Concerns through Social Anxiety and Privacy-Preserving Self-Efficacy. Sci Rep 15, 17414 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01737-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01737-1