Abstract

It has been shown that childhood trauma is associated with an increased risk of prodromal psychotic symptoms. However, research on the prevalence of prodromal psychotic symptoms among self-taught examination students and the relationship with childhood trauma remains limited. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of prodromal psychotic symptoms among self-taught examination students, explore the impact of childhood trauma on prodromal psychotic symptoms, and its underlying mechanisms. From January 5 to 18, 2024, a cross-sectional study was conducted on 670 self-taught examination students in Nantong University through the online survey platform “Wenjuanxing” (www.wjx.cn). These individuals completed the general information questionnaire, The childhood trauma questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF), The Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21). Data analysis was carried out using SPSS 25.0 and the PROCESS macro. (1) The prevalence of prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students was 20.6% (138/670); (2) The total effect of childhood emotional abuse and prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students was 2.9859. The mediating effect of anxiety (effect value: 1.4611), depression (effect value: 0.6201), social support (effect value: − 0.1214), and health conditions (effect value: 0.1954) in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and prodromal psychotic symptoms of self-taught examination students, accounts for 72.18% of the total effect. Childhood trauma can not only independently predict the risk of prodromal psychotic symptoms among self-taught examination students, but also predict the risk of prodromal psychotic symptoms indirectly by affecting anxiety, depression, social support, and health conditions. Targeted measures should be taken to reduce the prodromal psychotic symptoms in this neglected group of self-taught examination students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychotic experiences often involve positive symptoms like delusions and hallucinations1, as well as negative symptoms such as alogia, blunted affect, anhedonia, and avolition2. These occurrences can also arise in the general population and subclinical individuals3, with a prevalence of approximately 5% worldwide4. The onset of psychosis has a rough timeline with a series of stages, starting from the pre-symptomatic risk stage, followed by prodromal symptoms before psychosis, acute psychotic phase, and finally leading to chronic illness5. Prodromal psychotic symptoms are described as a period characterized by mental state features, representing the transition from premorbid functioning to the onset of clear psychotic features6,7. Investigations of prodromal psychotic symptoms have been conducted in studies of the psychosis experience in the general population8.Prodromal psychotic symptoms seen in the general population usually manifest mildly and possess biological attributes similar to those found in prevalent mental disorders, encompassing genetic predisposition, brain structure irregularities, and growth impairments9. Although experiencing psychotic episodes may not always lead to a clinical diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, they are linked to elevated distress and an increased risk of developing psychosis10. It’s widely recognized that college-aged students are a group particularly prone to experiencing stress and mental health challenges11. Two global surveys have shown that 20.3% and 35% of the surveyed university students have experienced at least one type of mental health disorder11,12. However, both surveys overlooked mental disorders or prodromal symptoms of mental illness, which peak in late adolescence and typically have lasting substantive effects on individuals13. In the university population, the prevalence of self-reported “prodromal syndrome” may be as high as 25%14.

Childhood trauma, defined as experiences of intense and distressing events during childhood that overwhelm a child’s ability to cope, has been linked to long-term negative effects on physical, emotional, and psychological well-being15. This includes forms of maltreatment such as emotional abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and sexual abuse16. It has been documented that childhood trauma is linked with a variety of mental health issues in adulthood17. Research has demonstrated a correlation between childhood trauma and heightened severity of clinical prodromal psychotic symptoms18. Moreover, the intensity of both the psychosis experience and symptoms tends to persist at elevated levels over time19,20, in clinical and subclinical populations, it is consistently associated with mixed psychopathology over the lifespan21,22,23.

The impact of childhood trauma on mental health outcomes, particularly depression, stems from the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors24. Adverse experiences during childhood can disrupt normal brain development, leading to alterations in stress response systems and emotional regulation, which in turn predispose individuals to depressive symptoms25. Experiencing childhood trauma can elevate a person’s chances of developing depression by four times26. In addition, the psychological scars left by childhood trauma, such as feelings of helplessness, worthlessness, and distorted self-perceptions, contribute to the vulnerability of college students to depression. Childhood trauma is an important predictor of depression among college students27,28. The consequences of childhood trauma can persist into adulthood and negatively impact an individual’s mental health29. Moreover, individuals who experienced childhood trauma may struggle with maintaining relationships30. Guo et al.31 found that individuals with higher levels of childhood trauma experienced increased levels of anxiety. Various studies have established that there is a significant positive correlation between childhood trauma and anxiety among college students32,33. In a study involving a community sample, it was discovered that 27% of adolescents and young adults exhibiting symptoms of anxiety/depression reported instances of prodromal psychotic symptoms34. Additionally, the study revealed that approximately 46% of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia experience moderate to severe symptoms of depression35, and a significant percentage of people with depression report experiencing prodromal psychotic symptoms at some point in their lives36, so depression and anxiety may increase the risk of developing prodromal psychotic symptoms. We hypothesize that depression and anxiety mediate between childhood trauma and prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students.

A birth cohort suggests that adverse experiences in childhood increase the risk of health outcomes because child maltreatment has harmful and lasting neurobiological effects on the developing brain, and the effects of this risk of health problems are not influenced by social or long-term changes37. A lot of research has shown that teens childhood trauma will increase the risk of health-related38,39,40. Physical health problems can also affect whether college students develop mental symptoms41. Studies has indicated a link between certain physical health issues like chronic diseases, neurological disorders, pain, sleep disturbances, and prodromal psychotic symptoms42,43,44. Childhood maltreatment also reduces social support and leads to the development of prodromal psychotic symptoms, and social support mediates childhood trauma and prodromal psychotic symptoms45. In addition, one study showed that social support of college students during COVID-19 mediated the overall impact of childhood trauma on mental health symptoms46.

From the perspective of developmental psychopathology47, childhood is crucial for an individual’s physical and mental development, and childhood trauma can deeply affect the psychological development trajectory. As the initial variable, childhood trauma like abuse or neglect can cause abnormal development in brain areas related to emotional regulation and cognitive processing. This makes individuals more likely to experience emotional dysregulation when facing stress, which first shows as depression and anxiety. Long-term depression and anxiety impair cognitive functions, affecting how individuals perceive and cope with their surroundings. Meanwhile, childhood trauma disrupts the social support system48. Trauma-experienced individuals often struggle with interpersonal communication, leading to a lack of social support48. Without it, they’re more vulnerable under stress. Moreover, childhood trauma can trigger physical symptoms. Prolonged psychological stress weakens the immune system, increasing the risk of physical problems like headaches and gastrointestinal discomfort49. These symptoms add to the psychological burden. Depression, anxiety, lack of social support, and physical symptoms interact and together lead to the emergence of prodromal symptoms of psychosis. Under long-term adverse psychological and physical states, an individual’s mental state becomes abnormal, showing symptoms like pre-experiences of hallucinations, delusions, and abnormal behaviors50. In summary, taking childhood trauma as the initial variable, manifested through intermediate variables such as depression, anxiety, lack of social support, and physical symptoms, ultimately converges to heighten the likelihood of the emergence of prodromal symptoms of psychosis, highlighting the need for in-depth research and proactive preventive measures.

To enter university, young people in China need to take the annual competitive National College Entrance Examination (CEE), commonly known as the Gaokao51. The Gaokao is defined as the most important event in the lives of Chinese students, as the scores achieved in this examination determine whether one can gain admission to university52. However, not all students succeed in gaining direct admission to universities after high school. Self-taught examination students are individuals of average learning ability who fail in the college entrance examination and are unable to enter undergraduate courses. After obtaining associate degree, they aim to further their education to meet societal demands, demonstrating a proactive attitude towards self-improvement. These students enroll in certain colleges or universities where they can receive assistance in their studies. They adopt a full-time learning mode, primarily focusing on self-study while receiving guidance from teachers, with the goal of obtaining a nationally recognized undergraduate degree within a 2-year period. Numerous studies in China have already shown the significance of focusing on this group’s mental health. For example, Lin53 found that the detection rate of psychological problems among self-taught students was 16.08%. Another study by He Hong54 indicated that the mental health problems of adult education self-taught students in Chongqing were more prevalent than the national norm. These studies highlight the existing mental health issues within this group, which are worthy of further in-depth exploration. Self-taught examination students constitute a distinct cohort. Based on the Stress-Vulnerability Model55, individuals with pre-existing vulnerabilities, especially those with a history of childhood trauma, are at an elevated risk of developing mental health problems under such long-term stress. Furthermore, self-taught examination students are an understudied and vulnerable group. Despite their unwavering commitment to academic success, their mental health requirements have been largely neglected. Currently, research on this group remains in its nascent stage. However, studying them holds substantial significance for the development of targeted mental health support mechanisms and for informing relevant policies.

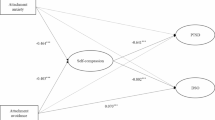

While previous research has found a strong relationship between childhood trauma and prodromal psychotic symptoms, the potential mechanisms through which childhood trauma influences prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students remain unclear. Therefore, this study aims to: (1) investigate the prevalence of prodromal psychotic symptoms in Chinese self-taught examination students, (2) propose the following hypothesis: anxiety, depression, physical conditions, and social support act as mediators in the influence of childhood trauma on prodromal psychotic symptoms. The research hypothesis model was shown in Fig. 1. The research findings can inform the development of targeted mental health interventions, helping to improve their mental health and strengthen the alternative education system in China.

Materials and methods

Participants

Jiangsu Province is the demonstration province of self-study examination in China, and Nantong University is the representative city of self-taught examination in Jiangsu, so the self-taught examination students of Nantong University are representative. From January 5 to 18, 2024, an online questionnaire survey was conducted at Nantong University in Nantong City, China using an online application (Wenjuanxing). Before administering the survey, we shared the survey link with faculty members, graduate students, and undergraduate students for a trial run and sought their input on the survey content and design. Following several revisions, the counselors sent the link and QR code to class leaders for students to complete the questionnaire autonomously. The questionnaire is filled out in class, and class leaders for students use uniform guidelines to guide students to fill out the questionnaire. In order to ensure the quality of the questionnaire, the questionnaire is completed as part of the course assessment. Prior to completing the questionnaire, all students were informed of the principles including the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, confidentiality, duration of the study, and data retention. All participants were self-taught examination students. Incomplete or obviously problematic questionnaires were excluded. A total of 685 students completed the survey, with 670 valid responses, representing an effective rate of 97.8%. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All participants were notified of their right to withdraw from the study at any point. Consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study. The procedures followed in this study adhere to the ethical standards established by pertinent national and institutional committees and align with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Sixth People’s Hospital of Nantong (NTLYLL2023016).

Measurement

General information questionnaire

Based on the research objectives and interviews with counselors and self-taught examination students, a general information questionnaire was designed. The survey was structured into two parts: the first part collected demographic data including gender, age, residence, monthly living expenses, only child, and personality; the second part focused on relevant academic and daily life information, such as major, work experience, grade, academic performance, weekly exercise frequency, physical conditions, number of friends, current relationship status, future planning, social support. Physical conditions were classified as healthy, general, or poor. Loneliness refers to the degree of isolation that self-taught examination students feel in their studies and daily life, including the sense of being alone when facing academic challenges and the lack of emotional support in their educational journey. Self-abasement specifically denotes the sense of inferiority that these students experience due to their self-taught status. Ratings were given on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 indicating “none” and 10 indicating “very high.” Social support is measured on a scale of 1–10, reflecting perceived support from family, school, friends, and significant others, with higher scores indicating less perceived social support.

The prodromal questionnaire-brief (PQ-B)

The PQ-B56 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire designed to evaluate prodromal psychotic symptoms. Respondents use a “yes” or “no” format to indicate whether each symptom is present. The total score corresponds to the count of “yes” responses. If a symptom is affirmed, respondents are prompted to assess the level of distress it causes using a five-point Likert scale, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, in response to the question "When this occurs, I feel scared, worried, or it causes problems for me." The distress score is derived from the sum of Likert scale ratings for each item in the PQ-B. The total score, ranging from 0 to 105, is calculated by adding up the scores for each item. The Chinese version of PQ-B has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89757. Wu et al.57 proposed cutoff scores of 7 and 24 for the total score and distress score of the Chinese version of the PQ-B, respectively.

The childhood trauma questionnaire-short form (CTQ-SF)

The CTQ-SF questionnaire comprises 28 items assessing the intensity of five categories of childhood trauma: emotional abuse (EA), emotional neglect (EN), physical abuse (PA), physical neglect (PN), and sexual abuse (SA). It is utilized to recognize instances of abuse or neglect experienced during childhood58. Each question is rated on a five-point Likert scale and the total score reflects the overall traumatic experiences during childhood. If any of the five sub-scales reach a specific threshold (EA ≥ 13, EN ≥ 15, PA ≥ 10, PN ≥ 10, or SA ≥ 8), individual is considered to have childhood trauma. The Chinese version of the short-form CTQ-SF has been extensively employed and shown strong validity and reliability in diverse population groups59.

The depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21)

DASS-21 is a self-administered questionnaire designed to assess negative emotions through three subscales, each comprising 7 items: depression, anxiety, and stress60. Participants provide ratings using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not applicable to me at all) to 3 (very applicable to me most of the time), with higher scores indicating increased frequency of negative experiences within the previous week. Subscale scores are calculated by summing the responses to the individual items within each subscale. The total score of the three dimensions is multiplied by 2. The standard decibels for the evaluation of the three dimensions are the total score of stress > 14, the total score of anxiety > 7, and the total score of depression > 9. DASS-21 has been utilized in evaluating the mental well-being of individuals in China61.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and composition ratios, were employed to analyze general characteristics. Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used to examine variations among demographic groups. Pearson linear correlation analysis was utilized to analyze the relationship between quantitative data, while Spearman rank correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation between rank data. The impact of each scale on psychological symptom scores was analyzed using multiple stepwise linear regression analysis. The relationships between variables were explored using parallel mediation models. Bootstrap method (5000 times) was used to test the mediation effects and provide a 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 25.0, IBM Corp) and SPSS PROCESS macro (version 4.1). All graphs were generated using R version 3.6.2. The significance level for all statistical analyses was set at P ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed) to control for Type I errors.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The final analysis included a total of 670 self-taught examination students. The mean age between 18 and 30 years old was 21.10 ± 1.44, with 233 males (34.8%) and 437 females (65.2%). There were statistically significant differences in personality (P = 0.001), physical conditions (P < 0.001), mental state (P < 0.001), and non-suicidal self-injury (P < 0.001). The details were shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 2, 138 self-taught examination students (20.6%) presented with prodromal psychotic symptoms. In addition, the incidence rates of EA, PA, SA, EN, and PN were 3.1% (21 cases), 4.6% (31 cases), 5.8% (39 cases), 26.9% (180 cases), and 26.7% (179 cases), respectively. 8.1% (54 cases) had stress, 24.2% (162 cases) had anxiety, and 20.9% (140 cases) had depression.

Correlation analysis of variables

The pearson correlation between PQ-B and continuous variables was shown in Table 3. PQ-B is associated with stress (r = 0.632, P < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.696, P < 0.001), depression (r = 0.659, P < 0.001), DASS-21 (r = 0.693, P < 0.001), EA (r = 0.473, P < 0.001), PA (r = 0.317, P < 0.001), SA (r = 0.227, P < 0.001), EN (r = 0.151, P < 0.001), PN (r = 0.236, P < 0.001), CTQ-SF (r = 0.344, P < 0.001) were correlated. Among the correlations between CTQ-SF and PQ-B, the EA dimension of CTQ-SF was the most closely related to PQ-B (r = 0.473, P < 0.001).

The spearman correlation between PQ-B and continuous variables was shown in Table 4. PQ-B is associated with academic performance (r = 0.086, P < 0.05), weekly exercise (r = − 0.093, P < 0.05), physical conditions (r = 0.312, P < 0.001), self-abasement (r = 0.277, P < 0.001), loneliness (r = 0.340, P < 0.001), social support (r = − 0.242, P < 0.001) were correlated.

Results of multiple stepwise linear regression analysis on PQ-B

The variables that are meaningful for single factor analysis with PQ-B are included in the multiple linear regression model, as shown in Table 5, anxiety (95% CI 0.868–1.130, P < 0.001), EA (95% CI 0.434–1.228, P < 0.001), physical conditions (95% CI: 1.620–4.894, P < 0.001), depression (95% CI 0.184–0.656, P = 0.001), and social support (95% CI − 1.394- − 0.156, P = 0.014) were statistically significant. In the childhood trauma questionnaire, only the emotional abuse dimension entered the multiple stepwise linear regression model. This suggests that, in our dataset, EA has a unique and significant impact on prodromal psychotic symptoms, independent of other types of childhood trauma. The absence of multicollinearity in our model is confirmed by Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values all being less than 5, indicating that each predictor variable is sufficiently independent and not unduly influenced by others in the model62.

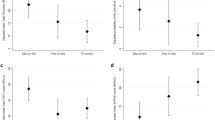

Mediation analyses

In mediation models, the R2 value reflects the proportion of variance in the outcome variable (PQ-B scores) explained by the model. The range of R2 values is from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger explanatory power of the model for the data63. In accordance with our initial mediation hypothesis model, we included variables that were significant for multiple stepwise linear regression analysis. In the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, only the emotional abuse (EA) dimension entered the multiple stepwise linear regression model. Moreover, the EA model demonstrated the highest explanatory power, with an R2 value of 0.528, which indicates that it better explains the variance in prodromal psychotic symptoms compared to other dimensions of childhood trauma. Therefore, we refined our model by using EA as the X variable and psychiatric symptoms as the Y variable, which allows for a more accurate representation of the relationship between childhood trauma and psychiatric symptoms. The constructed model is shown in Fig. 2. In mediation analysis, the effect value measures the strength and direction of the relationship between variables, with three key types: the total effect (overall impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable without considering the mediator), the direct effect (impact when holding the mediator constant), and the indirect effect (impact through the mediator). A positive effect value indicates a positive relationship, while a negative value indicates a negative relationship. A significant indirect effect, regardless of its sign, demonstrates that the mediator influences the relationship between the independent and dependent variables64. As shown in Table 6, the total effect of emotional abuse to PQ-B was 2.9859 (β = 0.2151, 95% CI 2.5637–3.4082), and the direct effect was 0.8307 (β = 0.2151, 95% CI 0.4337–1.2277), the indirect effect was 2.1552 (β = 0.3049, 95% CI 1.6051–2.7844), the indirect effect accounted for 72.18%. In the four indirect effects, Emotional abuse → Anxiety → Prodromal psychotic symptoms was 1.4611 (β = 0.2880, 95% CI 0.9329–2.0671), accounting for 43.98% of the total effect. Emotional abuse → Depression → Prodromal psychotic symptoms was 0.6201(β = 0.2338, 95% CI 0.1846–1.1134), accounting for 18.67% of the total effect. Emotional abuse → Social Support → Prodromal psychotic symptoms was − 0.1214 (β = 0.0503, 95% CI − 0.2278 to − 0.0264) accounted for 3.65% of the total effect. Emotional abuse → Physical conditions → Prodromal psychotic symptoms was 0.1954(β = 0.0798, 95% CI 0.0586–0.3721) accounted for 5.88% of the total effect.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that the incidence of prodromal psychotic symptoms among self-taught examination students was 20.6% (138/670). This incidence rate is lower than that reported in other studies on college students, where the incidence of prodromal psychotic symptoms was found to be 28%65. This may be because self-taught examination students are usually adult individuals with certain work experience or social experience, which may give them stronger psychological coping abilities when facing challenges. In addition, self-taught examination students require strong self-discipline and self-management skills, indicating that they may possess better psychological stability and resilience.

Our results show that emotional abuse in childhood can directly predict prodromal psychotic symptoms, which is consistent with previous findings18. Adversities in childhood are associated with a decrease in the volume of the hippocampus66. Childhood adversities in psychiatric patients have been linked to a blunted response in the HPA axis67. Hypervigilance, an abnormal state of heightened alertness resulting from trauma or severe stress, is characterized by increased levels of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, as well as alterations in the quantity or responsiveness of stress hormone receptors68. These changes may contribute to long-term dysregulation of the stress response system and increased vulnerability to mental health disorders69,70. The brain becomes sensitive to threats after experiencing trauma. When faced with a new source of stress, the body “remembers” past events and reacts excessively71. The neurodevelopmental model resulting from trauma delineates a neurobiological pathway connecting early trauma to negative symptoms via hypervigilance and the biological stress system72,73. All these factors and behaviors are considered potential symptoms of mental illness.

Childhood emotional abuse can also indirectly predict prodromal psychotic symptoms through anxiety. Childhood emotional abuse not only has a direct negative impact on individuals but can also exacerbate the development of prodromal psychotic symptoms through the triggering of persistent psychological stress responses, such as anxiety74. Specifically, anxiety may act as a mechanism through which early negative emotional experiences affect the formation and development of later psychopathology75. This impact is particularly pronounced in the specific group of self-studying students. Due to the pressures of study and employment faced by self-studying students, they may be more susceptible to experiencing anxiety provoked by early emotional abuse76, which in turn affects their prodromal psychotic symptoms. Given that self-taught examination students often need to study independently without the support of a traditional educational environment, this mode of learning may exacerbate their feelings of loneliness, thus exacerbating the mental health problems caused by emotional abuse in childhood50. Therefore, understanding the complex relationship between emotional abuse and mental health issues within this specific group is crucial for developing targeted psychological interventions77. Some self-taught exam candidates may experience emotional abuse in their childhood, such as family conflicts and strained parent–child relationships, which can lead to the emergence of anxiety74. Under China’s educational system, self-taught exam candidates face enormous academic pressure and societal expectations for their future success, which can exacerbate anxiety, especially in the context of childhood emotional abuse. This anxiety may serve as a catalyzing factor for the onset of early mental health symptoms74, exacerbating potential mental health issues in self-taught exam candidates.

Childhood emotional abuse can also indirectly predict prodromal psychotic symptoms through depression. When children encounter persistent emotional abuse, they might internalize negative messages about themselves and the world. Such negative cognitions can lay the groundwork for depressive thought patterns, characterized by persistent sadness, feelings of worthlessness, and a distorted view of self and others78. The learned helplessness that can emerge from this abuse often leads to a sense of a lack of control over one’s life, further contributing to depressive symptoms. Childhood trauma is associated with a 2–3 times increased risk of depression, and more than half of anxiety and depression cases worldwide may report experiences of childhood trauma79. The depressive state disrupts normal coping mechanisms and impairs the ability to manage life stressors effectively80. For self-taught examination students, the challenges of processing and overcoming the emotional scars left by childhood abuse are magnified if they lack a supportive and nurturing environment typically provided by educational institutions. The absence of such support can lead to increased feelings of isolation and helplessness, which intensify the symptoms of depression81. Consequently, without adequate intervention, the cycle of depression and related prodromal psychotic symptoms can persist and profoundly affect the psychological well-being of these individuals82. Experiences of emotional abuse during childhood can potentially result in permanent biological changes in the brain, which are closely linked to the development of depression and other psychiatric conditions83,84. Moreover, from the perspective of the biopsychosocial model, these early negative experiences can affect the way individuals process cognition, making them more prone to developing negative self-concepts and worldviews, thereby increasing the risk of depression85. Among self-taught examination students, this impact may be particularly pronounced due to the lack of social and emotional support traditionally offered by educational support systems. The absence of a supportive social network and stress management mechanisms might make it more challenging for these individuals to cope with the psychological trauma associated with early emotional abuse, thereby facilitating the development of depressive symptoms.

Childhood emotional abuse can indirectly predict prodromal psychotic symptoms through its impact on perceived social support. Self-taught examination students who experienced emotional abuse in childhood often report lower levels of perceived social support in adulthood, which is associated with an increase in prepsychotic symptoms. This relationship can be explained by several mechanisms. First, emotional abuse impairs interpersonal functioning, leading to difficulties in forming and maintaining supportive relationships86,87. Second, negative self-perceptions stemming from emotional abuse, such as feelings of unworthiness, hinder individuals from seeking or accepting social support88,89. Third, chronic stress from emotional abuse dysregulates the stress response system, further exacerbating social isolation90. Lower social support, in turn, increases stress sensitivity and vulnerability to prodromal psychotic symptoms, such as attenuated hallucinations and cognitive disturbances91,92,93. These findings highlight the importance of addressing social support deficits in interventions aimed at mitigating the mental health risks associated with childhood emotional abuse, particularly among vulnerable populations like self-taught examination students.

Childhood emotional abuse can also indirectly predict prodromal psychotic symptoms through physical conditions. Research has established a strong association between physical health and mental health94,95. Physical health issues such as chronic pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances have been shown to be intertwined with mental health conditions96. Therefore, the impact of childhood emotional abuse on physical health may serve as an early indicator of potential mental health implications among self-taught examination students. The biopsychosocial model is a widely used theoretical framework that explains the influences of biological, psychological, and social factors on health and disease97. Childhood emotional abuse may disrupt biological systems such as the neuroendocrine and immune systems, contributing to physical health challenges and increasing the vulnerability to mental health issues98. The model underscores the importance of considering the holistic well-being of individuals, particularly those with a history of childhood adversity. Childhood emotional abuse can trigger chronic stress responses and psychological trauma, leading to dysregulated stress response system 99.These psychophysiological changes may impact both physical health indicators and mental health symptoms, creating a complex interplay between stress, trauma, and overall well-being among self-taught examination students. Understanding the links between childhood emotional abuse, physical health indicators, and prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students highlights the importance of early intervention and comprehensive support strategies. Combining physical health assessments, screening for prodromal psychotic symptoms, and targeted interventions can help to predict and mitigate mental health challenges early, while also addressing the physical health needs of this vulnerable population.

There are some limitations in this study. First, data collection was predominantly sourced from a single university in China. This restricted sampling frame significantly constrains the representativeness of our sample. Self-taught examination students from diverse educational backgrounds, geographical regions, and age demographics are likely to have distinct experiences and characteristics. Second, the cross-sectional design employed in this study has inherent limitations when it comes to establishing causal relationships. A longitudinal study design would be essential to understand how these factors evolve and interact over the lifespan, providing a more accurate understanding of the underlying causal mechanisms. Third, there may be other factors, such as coping ability, that we did not include in this study but that could influence mental symptoms and thus affect our findings. Further exploration of these factors will be conducted in subsequent studies. Fourth, the interactions among the four hypothesized pathways from childhood trauma to prodromal psychotic symptoms have not been fully explored. For example, it remains unclear how depression and anxiety interact with each other and jointly contribute to the outcome, which undermines the comprehensiveness of the analysis. Fifth, the absence of a control group is a significant limitation. Including a control group, such as a sample of traditional university students, would have allowed for a more robust comparison and provided a clearer understanding of the unique impact of self-taught examination status on the prevalence of prodromal psychotic symptoms. Future research should consider including a control group to better understand the unique impact of self-taught examination status on the prevalence of prodromal psychotic symptoms. This would help in isolating the specific factors associated with self-taught examination students and provide a more robust comparison.

Conclusion

In conclusion, childhood trauma not only directly impacts the prodromal psychotic symptoms of self-taught examination students but can also indirectly affect prodromal psychotic symptoms through depression, anxiety, social support, and physical health. Preventing childhood trauma, reducing negative emotions such as depression and anxiety, enhancing social support, and maintaining physical health can reduce the occurrence of prodromal psychotic symptoms, providing theoretical and practical basis for the prevention and intervention of prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students.

Data availability

The raw data of the current study would be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shafer, A. & Dazzi, F. Meta-analytic exploration of the joint factors of the brief psychiatric rating scale: Expanded (BPRS-E) and the positive and negative symptoms scales (PANSS). J. Psychiatr. Res. 138, 519–527 (2021).

Kirkpatrick, B., Fenton, W. S., Carpenter, W. T. Jr. & Marder, S. R. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 32(2), 214–219 (2006).

Staines, L. et al. Psychotic experiences in the general population, a review; definition, risk factors, outcomes and interventions. Psychol. Med. 52(15), 1–12 (2022).

van Os, J., Linscott, R. J., Myin-Germeys, I., Delespaul, P. & Krabbendam, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: Evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol. Med. 39(2), 179–195 (2009).

Insel, T. R. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature 468(7321), 187–193 (2010).

Yung, A. R. & McGorry, P. D. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: Past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr. Bull. 22(2), 353–370 (1996).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. The psychosis high-risk state: A comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiat. 70(1), 107–120 (2013).

Johns, L. C. et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported psychotic symptoms in the British population. Br. J. Psychiatry 185, 298–305 (2004).

Kelleher, I. & Cannon, M. Psychotic-like experiences in the general population: Characterizing a high-risk group for psychosis. Psychol. Med. 41(1), 1–6 (2011).

Nelson, B., Fusar-Poli, P. & Yung, A. R. Can we detect psychotic-like experiences in the general population?. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18(4), 376–385 (2012).

Auerbach, R. P. et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Psychol. Med. 46(14), 2955–2970 (2016).

Auerbach, R. P. et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127(7), 623–638 (2018).

Sullivan, S. A. et al. A population-based cohort study examining the incidence and impact of psychotic experiences from childhood to adulthood, and prediction of psychotic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 177(4), 308–317 (2020).

Loewy, R. L., Johnson, J. K. & Cannon, T. D. Self-report of attenuated psychotic experiences in a college population. Schizophr. Res. 93(1–3), 144–151 (2007).

Felitti, V. J. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14(4), 245–258 (1998).

Zalsman, G. & Brent, D. A. Weersing VR Depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence: An overview—epidemiology, clinical manifestation and risk factors. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 15(4), 827–841 (2006).

Xie, P. et al. Prevalence of childhood trauma and correlations between childhood trauma, suicidal ideation, and social support in patients with depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia in southern China. J. Affect. Disord. 228, 41–48 (2018).

Varese, F. et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: A meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr. Bull. 38(4), 661–671 (2012).

Garcia, M. et al. Sex differences in the effect of childhood trauma on the clinical expression of early psychosis. Compr. Psychiatry 68, 86–96 (2016).

Trotta, A., Murray, R. M. & Fisher, H. L. The impact of childhood adversity on the persistence of psychotic symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 45(12), 2481–2498 (2015).

Hughes, K. et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2(8), e356–e366 (2017).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 197(5), 378–385 (2010).

van Nierop, M. investigators OUoP et al. Childhood trauma is associated with a specific admixture of affective, anxiety, and psychosis symptoms cutting across traditional diagnostic boundaries. Psychol. Med. 45(6), 1277–1288 (2015).

Heim, C. & Nemeroff, C. B. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biol. Psychiatry 49(12), 1023–1039 (2001).

Dehghan Manshadi, Z., Neshat-Doost, H. T. & Jobson, L. Cognitive factors as mediators of the relationship between childhood trauma and depression symptoms: The mediating roles of cognitive overgeneralisation, rumination, and social problem-solving. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 15(1), 2320041 (2024).

Felitti, V. J. et al. REPRINT of: Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 56(6), 774–786 (2019).

Wang, J., He, X., Chen, Y. & Lin, C. Association between childhood trauma and depression: A moderated mediation analysis among normative Chinese college students. J. Affect. Disord. 276, 519–524 (2020).

Chang, J. J., Ji, Y., Li, Y. H., Yuan, M. Y. & Su, P. Y. Childhood trauma and depression in college students: Mediating and moderating effects of psychological resilience. Asian J. Psychiatr. 65, 102824 (2021).

Wakuta, M. et al. Adverse childhood experiences: Impacts on adult mental health and social withdrawal. Front Public Health 11, 1277766 (2023).

O’Shields, J., Mowbray, O. & Cooper, Z. The effects of childhood maltreatment on social support, inflammation, and depressive symptoms in adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 340, 116481 (2024).

Guo, J., Fu, M., Liu, D., Zhang, B. & Wang, X. van IMH: Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 110(Pt 2), 104667 (2020).

Loewy, R. L. et al. Childhood trauma and clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 205, 10–14 (2019).

Euser, S., Alink, L. R., Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. A gloomy picture: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reveals disappointing effectiveness of programs aiming at preventing child maltreatment. BMC Public Health 15, 1068 (2015).

Wigman, J. T. et al. Evidence that psychotic symptoms are prevalent in disorders of anxiety and depression, impacting on illness onset, risk, and severity–implications for diagnosis and ultra-high risk research. Schizophr. Bull. 38(2), 247–257 (2012).

Subodh, B. N. & Grover, S. Depression in schizophrenia: Prevalence and its impact on quality of life, disability, and functioning. Asian J. Psychiatry 54, 102425 (2020).

Ohayon, M. M. & Schatzberg, A. F. Prevalence of depressive episodes with psychotic features in the general population. Am. J. Psychiatry 159(11), 1855–1861 (2002).

Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Giles, W. H. & Anda, R. F. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev. Med. 37(3), 268–277 (2003).

Wang, H., Wang, Z., Li, X. & Liu, J. Characteristics and risk factors of health-related risky behaviors in adolescents with depression. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 18(1), 34 (2024).

Counts, C. J. & John-Henderson, N. A. Childhood trauma and college student health: A review of the literature. J. Am. Coll. Health 72(8), 2783–2797 (2023).

Kleih, T. S. et al. Exposure to childhood maltreatment and systemic inflammation across pregnancy: The moderating role of depressive symptomatology. Brain Behav. Immun. 101, 397–409 (2022).

Oh, H., Banawa, R., Zhou, S., DeVylder, J. & Koyanagi, A. The mental and physical health correlates of psychotic experiences among US college students: Findings from the Healthy Mind Study 2020. J. Am. Coll. Health 72(3), 834–840 (2024).

Gerrits, M. M., van Marwijk, H. W., van Oppen, P., van der Horst, H. & Penninx, B. W. The role of somatic health problems in the recognition of depressive and anxiety disorders by general practitioners. J. Affect. Disord. 151(3), 1025–1032 (2013).

Choi, J., Kang, J., Kim, T. & Nehs, C. J. Sleep, mood disorders, and the ketogenic diet: potential therapeutic targets for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 15, 1358578 (2024).

Parker, A. et al. Injustice, quality of life, and psychiatric symptoms in people with migraine. Rehabil. Psychol. 68(1), 77–90 (2023).

Zhao, J., Peng, X., Chao, X. & Xiang, Y. Childhood maltreatment influences mental symptoms: The mediating roles of emotional intelligence and social support. Front. Psychiatry 10, 415 (2019).

Hong, W. et al. Home quarantine during COVID-19 blunted childhood trauma-related psychiatric symptoms in Chinese college students. Front. Public Health 11, 1073141 (2023).

Kwok, S., Gu, M. & Kwok, K. Childhood emotional abuse and adolescent flourishing: A moderated mediation model of self-compassion and curiosity. Child Abuse Negl. 129, 105629 (2022).

Ahouanse, R. D. et al. Childhood maltreatment and suicide ideation: A possible mediation of social support. World J. Psychiatry 12(3), 483–493 (2022).

Devi, S. et al. Heath WR et al Adrenergic regulation of the vasculature impairs leukocyte interstitial migration and suppresses immune responses. Immunity 54(6), 1219-1230e1217 (2021).

Strathearn, L. et al. Long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0438 (2020).

Zheng, M. & Ruan, C. The new college entrance examination reform investigation and research on comprehensive quality evaluation. Heliyon 10(19), e38269 (2024).

Chen, Y., Jiang, M. & Kesten, O. An empirical evaluation of Chinese college admissions reforms through a natural experiment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117(50), 31696–31705 (2020).

Lin, X. Investigation into the mental health of self-taught examinees and analysis of educational countermeasures. Chin. Adult Educ. 20, 126–128 (2010).

He, H. Coping styles and mental health of self-taught students in adult education in Chongqing city. J. Chongqing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 27(06), 86–88 (2010).

Mueser, K. T., Rosenberg, S. D., Goodman, L. A. & Trumbetta, S. L. Trauma, PTSD, and the course of severe mental illness: An interactive model. Schizophr. Res. 53(1–2), 123–143 (2002).

Loewy, R. L., Bearden, C. E., Johnson, J. K., Raine, A. & Cannon, T. D. The prodromal questionnaire (PQ): Preliminary validation of a self-report screening measure for prodromal and psychotic syndromes. Schizophr. Res. 79(1), 117–125 (2005).

Xu, L. et al. Psychometric properties of prodromal questionnaire-brief version among Chinese help-seeking individuals. PLoS ONE 11(2), e0148935 (2016).

Bernstein, D. P. et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 27(2), 169–190 (2003).

Qi, M. et al. The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 67(4), 514–518 (2020).

Lovibond, P. F. & Lovibond, S. H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33(3), 335–343 (1995).

Wang, K. et al. Cross-cultural validation of the depression anxiety stress scale-21 in China. Psychol. Assess. 28(5), e88–e100 (2016).

Schneider, A., Hommel, G. & Blettner, M. Linear regression analysis: Part 14 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 107(44), 776–782 (2010).

Alexander, D. L., Tropsha, A. & Winkler, D. A. Beware of R(2): Simple, unambiguous assessment of the prediction accuracy of QSAR and QSPR models. J. Chem. Inf. Model 55(7), 1316–1322 (2015).

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J. & Fritz, M. S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58, 593–614 (2007).

Saavedra, J. L. et al. The cascade of care for early psychosis detection in a college counseling center. Psychiatr. Serv. 75(2), 161–166 (2024).

Teicher, M. H., Anderson, C. M. & Polcari, A. Childhood maltreatment is associated with reduced volume in the hippocampal subfields CA3, dentate gyrus, and subiculum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109(9), E563-572 (2012).

Hakamata, Y., Suzuki, Y., Kobashikawa, H. & Hori, H. Neurobiology of early life adversity: A systematic review of meta-analyses towards an integrative account of its neurobiological trajectories to mental disorders. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 65, 100994 (2022).

Slopen, N., McLaughlin, K. A. & Shonkoff, J. P. Interventions to improve cortisol regulation in children: A systematic review. Pediatrics 133(2), 312–326 (2014).

Arcego, D. M. et al. A Glucocorticoid-sensitive hippocampal gene network moderates the impact of early-life adversity on mental health outcomes. Biol. Psychiatry 95(1), 48–61 (2024).

Menke, A. et al. Childhood trauma dependent anxious depression sensitizes HPA axis function. Psychoneuroendocrinology 98, 22–29 (2018).

Herringa, R. J. Trauma, PTSD, and the developing brain. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19(10), 69 (2017).

Fisher, H. L. et al. Pathways between childhood victimization and psychosis-like symptoms in the ALSPAC birth cohort. Schizophr. Bull. 39(5), 1045–1055 (2013).

Isvoranu, A. M. et al. A network approach to psychosis: Pathways between childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Schizophrl. Bull. 43(1), 187–196 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal cohort studies on the impact of childhood traumas on anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 374, 443–459 (2025).

Yu, Y. et al. Linear and curvilinear association of pain tolerance and social anxiety symptoms among youth with different subtgroups of childhood trauma. J. Affect. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.03.087 (2024).

Wang, Z. J., Liu, C. Y., Wang, Y. M. & Wang, Y. Childhood psychological maltreatment and adolescent depressive symptoms: Exploring the role of social anxiety and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. J. Affect. Disord. 344, 365–372 (2024).

Panter-Brick, C., Goodman, A., Tol, W. & Eggerman, M. Mental health and childhood adversities: A longitudinal study in Kabul, Afghanistan. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50(4), 349–363 (2011).

Oymak Yenilmez, D. et al. Relationship between childhood adversities, emotion dysregulation and cognitive processes in bipolar disorder and recurrent depressive disorder. Turk. Psikiyatri. Derg. 32(1), 8–16 (2021).

Li, M., D’Arcy, C. & Meng, X. Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychol. Med. 46(4), 717–730 (2016).

Tartt, A. N., Mariani, M. B., Hen, R., Mann, J. J. & Boldrini, M. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: Pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol. Psychiatry 27(6), 2689–2699 (2022).

Gariepy, G., Honkaniemi, H. & Quesnel-Vallee, A. Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in Western countries. Br. J. Psychiatry 209(4), 284–293 (2016).

Dubovsky, S. L., Ghosh, B. M., Serotte, J. C. & Cranwell, V. Psychotic depression: Diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Psychother. Psychosom. 90(3), 160–177 (2021).

LeMoult, J. et al. Meta-analysis: Exposure to early life stress and risk for depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 59(7), 842–855 (2020).

Humphreys, K. L. et al. Child maltreatment and depression: A meta-analysis of studies using the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 102, 104361 (2020).

Seo, E. et al. Trait attributions and threat appraisals explain why an entity theory of personality predicts greater internalizing symptoms during adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 34(3), 1104–1114 (2022).

McKay, M. T. et al. Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 143(3), 189–205 (2021).

Dvir, Y., Ford, J. D., Hill, M. & Frazier, J. A. Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 22(3), 149–161 (2014).

Steenkamp, L. R. et al. Childhood trauma and real-world social experiences in psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 252, 279–286 (2023).

Shahar, B., Doron, G. & Szepsenwol, O. Childhood maltreatment, shame-proneness and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder: A sequential mediational model. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 22(6), 570–579 (2015).

Corrigan, F. M., Fisher, J. J. & Nutt, D. J. Autonomic dysregulation and the window of tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. J. Psychopharmacol. 25(1), 17–25 (2011).

Myin-Germeys, I. & van Os, J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: Evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 27(4), 409–424 (2007).

Veling, W., Pot-Kolder, R., Counotte, J., van Os, J. & van der Gaag, M. Environmental social stress, paranoia and psychosis liability: A virtual reality study. Schizophr. Bull. 42(6), 1363–1371 (2016).

Veling, W., Counotte, J., Pot-Kolder, R., van Os, J. & van der Gaag, M. Childhood trauma, psychosis liability and social stress reactivity: A virtual reality study. Psychol. Med. 46(16), 3339–3348 (2016).

Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E. & Sutton, M. The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 195, 42–49 (2017).

Barch, D. M. et al. Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 55–66 (2018).

Constantino, J. N. Bridging the divide between health and mental health: New opportunity for parity in childhood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 62(11), 1182–1184 (2023).

Bolton, D. A revitalized biopsychosocial model: Core theory, research paradigms, and clinical implications. Psychol. Med. 53(16), 7504–7511 (2023).

Tang, R. et al. Adverse childhood experiences, DNA methylation age acceleration, and cortisol in UK children: A prospective population-based cohort study. Clin. Epigenet. 12(1), 55 (2020).

Kaufman, J. et al. The corticotropin-releasing hormone challenge in depressed abused, depressed nonabused, and normal control children. Biol. Psychiatry 42(8), 669–679 (1997).

Funding

This work was supported by Major Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Association for Degrees and Graduate Education (JSSYXHZD2023-1) and Subproject of Jiangsu Provincial Association for Degrees and Graduate Education (JSYXHXM2023-ZYB21). The funding sources had no role to play in the study design, the collection and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or decision to submit this paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and D.W. conceived the manuscript. Y.W. and J.G. drafted the manuscript and made substantial contributions to the data analysis and interpretation. J.W. revised the article critically for important intellectual content. Y.C., X.C., and W.S. were involved in the data collection, and participated in the revision of the manuscript. J.G. and Q.X. jointly proposed the research idea. J.G. played a supervisory role and provided the final approval for the version to be published.All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of The Sixth People’s Hospital of Nantong (NTLYLL2023016). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki). All participants consented and participated voluntarily.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wu, D., Wang, J. et al. Mediational effect analysis of childhood emotional abuse on prodromal psychotic symptoms in self-taught examination students. Sci Rep 15, 19932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05062-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05062-5