Abstract

While negative risk-taking behavior in adolescents is a classic topic, extant research has long spent little attention to the positive aspects of adolescents’ development. One topic that started to gain more research focus is prosocial risk-taking behavior—defined as behavior where an individual takes a risk to help someone else. However, validated measures are still limitedly available. The goal of the study is to construct and validate a multifaceted measure to assess prosocial risk-taking in adolescents. A sample of 234 Dutch adolescents (149 girls) aged 14–17 filled in the unvalidated prosocial adolescent risk-taking questionnaire (PAR-Q) to perform iterative exploratory factor analyses to indicate initial factor structure. A separate data sample of 357 Dutch adolescents (208 girls) aged 14–17 filled in the PAR-Q to confirm this factor structure with iterative confirmatory factor analyses and additional questionnaires for convergent validity. In this sample, also test–retest reliability was assessed. The final two-factor structure, which represented Social and Material prosocial risk subscales, exhibited acceptable internal consistency and excellent test–retest reliability. The PAR-Q correlated positively with prosocial behaviors and empathy. The PAR-Q is a newly validated measure with adequate psychometric properties that can be used to gain more information on prosocial risk-taking behavior in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence is a period known for its high prevalence of risk-taking behavior1,2. Previous research has mainly focused on negative aspects of risk-taking behavior including traffic related risk-taking such as speeding, alcohol use and gambling. However, risk-taking behavior is generally defined as behavior with variable and uncertain outcomes3,4. This implies that risk-taking can be either beneficial or detrimental. Recently, the focus has shifted towards more positive forms of adolescent risk-taking. One positive form of risk-taking is prosocial risk-taking5. Gaining more knowledge about mechanisms that might promote prosocial risk-taking – in the future perhaps even learning how to stimulate this behavior over negative risk-taking – can be relevant from both a scientific and societal perspective. Developmentally, taking prosocial risks rather than negative or antisocial risks can contribute to healthy development in adolescence. Societally, promoting taking prosocial risks, especially in younger generations, can be beneficial for the society as a whole.

Prosocial risk-taking is defined as behavior where an individual takes a risk – social, physical or financial – to help someone else. Examples of prosocial risk-taking are standing up for someone being bullied with the risk of being a victim of bullying oneself or lending an item to a friend with the risk of receiving it damaged. Prosocial risk-taking behavior has been studied before in bullying literature6,7 and social psychology8,9,10. However, research in adolescence is limited. It is crucial for research in this area to develop solid measures of prosocial risk-taking. Currently only one instrument is available to assess prosocial risk-taking behavior in adolescents: the Prosocial Risk-Taking Scale by Armstrong-Carter and colleagues11. They were the first to develop a questionnaire on prosocial risk-taking behavior, providing an initial foundation for empirical research in this area9. This measure is novel and guided by theory5. However, the questionnaire focuses on social risks as well as on specific school contexts11. Here we aim to broaden the focus of the field by developing a questionnaire to investigate a broader representation of risks (e.g., including material risks) as well as a somewhat more extended array of contexts (e.g., school, sports, concerts). We refer to this assessment as the Prosocial Adolescent Risk-Taking Questionnaire (PAR-Q).

Defining prosocial risk-taking

Do and colleagues5 were first to suggest prosocial risk-taking as behavior on the intersection of prosocial and risk-taking behavior. Their theoretical framework suggests that prosocial risk-taking requires high scores on both the prosocial axis and the risk-taking axis and that these characteristics are key for displaying the behavior5. As prosocial risk-taking is considered a combination of prosocial and risk-taking behavior, both prosocial, as well as (negative) risk-taking behavior could influence prosocial risk-taking behavior5,11,12. However, empirical studies showing exactly how these concepts are related to prosocial risk-taking behavior are very limited. While little research has empirically assessed this, Armstrong-Carter et al. provided an initial attempt with their questionnaire on prosocial risk-taking behavior11.

Conceptually, prosocial risk-taking behavior could be seen as a variation of risk-taking behavior, similar to negative and antisocial, and, more recently defined, positive risk-taking behavior4. These variations of risk-taking behavior can be distinguished on the basis of valence of outcomes (positive versus negative) and the recipient of these outcomes (self, other, or both). For negative risk-taking behavior, for example binge drinking, the negative consequences are for the self. For antisocial risk-taking behavior, for example vandalism, the negative consequences are for the other. This could be similarly argued for prosocial risk-taking behavior, for example standing up for someone being bullied, where the positive outcome is for the other, even though the risk is still for the self. In positive risk-taking, for example asking someone out on a date or taking a difficult course in school, the positive outcome is for the self, as is the risk. If the authors’ proposed distinction is true, factors underlying negative risk-taking, could also be underlying prosocial risk-taking behavior, such as impulsivity13 and sensation-seeking14. For risk-taking behavior11,15, impulsivity15,16 and sensation seeking11,12,17 results that could suggest both negative and positive correlations with prosocial risk-taking behavior have been found.

These contradictory findings may result from the possibility that prosocial risk-taking behavior is a variation of prosocial behavior, rather than risk-taking behavior. Prosocial behavior is thought to be a very considerate process and has been related to self-regulation18 and effortful control19. Similar to prosocial risk-taking behavior, prosociality is considered a multidimensional construct20. It distinguishes between material and social or immaterial costs and benefits of prosocial behavior20. For prosocial behavior, a strong predictor is empathy21,22, which can be conceptualized in terms of cognitive12,23 and affective empathy11,22. These factors might also be related to prosocial risk-taking behavior. Conceptually, it is important to distinguish between prosocial risks and prosocial costs, which are often mentioned in the literature on prosocial behavior. Prosocial risks differ from prosocial costs in that they are explicitly probabilistic, whereas prosocial costs can be probabilistic. Although even prosocial costs, especially those in the future, have an element of chance, the consequences of prosocial risk-taking for the self are inherently unknown and uncertain.

As both prosocial and risk-taking behavior, prosocial risk-taking is a multifaceted construct and risks can pertain to different domains including reputational risks, financial risks and health-related risks (see also ref.20,24). How adolescents perceive risks might differ per ___domain. For example, adolescents might judge reputational and social risks differently than material or financial risks, as adolescents are known to highly value social rewards and standing24,25,26. Furthermore, prosocial risk-taking can be directed to and can occur in situations involving different people, broadly ranging from complete strangers to close friends. As adolescents are highly focused on peers and peer relationships, it is thought that social context can have a great influence on the decision-making process27,28.

Current study

The goal of the current study was to develop and validate an inclusive, multifaceted measure to assess prosocial risk-taking in different domains and situations in adolescents aged 14–17 years old. In the first phase, scale development, a pilot version of the questionnaire was tested and adapted. After this, an initial set of 29 items was constructed and data on these items were collected in two samples. In the second phase, to determine the factor structure of the questionnaire we performed an iterative exploratory factor analysis (EFA) process to identify the latent structure of the PAR-Q. In the third phase, using a different data set, iterative confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed to validate the resulting factor structure of the EFA. In a fourth and final phase, internal consistency, convergent validity and test–retest reliability of the constructed questionnaire were investigated. To assess convergent validity of the PAR-Q, participants in the CFA sample completed a set of other measures assessing related constructs. These measures included prosociality as assessed by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire prosocial subscale29 and Prosocial Tendencies Measure Revised30, cognitive and affective empathy as assessed by Interpersonal Reactivity Index, respectively perspective taking subscale and empathic concern subscale31. Furthermore, measures also included impulsivity as assessed by BIS-1132, sensation seeking as assessed by Nederlandse Schaal voor Gevoeligheid Verveling sensation seeking subscale33 and risk-taking behavior as assessed by Domain Specific Risk-Taking questionnaire24,34. To assess stability of the measure, a subset of participants completed the PAR-Q again approximately six weeks later. At the conclusion of our study, we present a validated questionnaire designed to assess prosocial risk-taking in adolescence.

Hypotheses

We expected that the factor analyses would result in a multidimensional scale, with each scale focusing on prosocial risk-taking in different domains. Furthermore, we expected that prosocial risk-taking is positively correlated with prosocial behavior5,11,12, cognitive empathy12,23 and affective empathy11,22. Furthermore, we expected prosocial risk-taking to be correlated with impulsivity, sensation seeking and risk-taking behavior, but given the current body of literature the predicted directionality of this effect is unclear.

Results

First, iterative data-driven exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted to identify the latent structure of the PAR-Q. The exploratory factor analyses were conducted in a sample of 234 adolescents (149 girls) aged 14 to 17 years old (Mage = 16.40, SD = 1.06). In a second data set, iterative confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed to confirm the resulting factor structure of the EFA. This second, separate sample consisted of 357 adolescents (208 girls) aged 14 to 17 years old (Mage = 16.06, SD = 1.12).

Exploratory factor analyses

The input of the iterative process of Exploratory Factor Analyses were the items with Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin values of 0.7 and higher (19 items in total). Per iteration, one item was deleted based on predefined conditions. First, the item loadings were checked for items with loading < 0.3, where the lowest item loading was deleted and the EFA was rerun. When all items loaded > 0.3, cross-loadings were examined. Per iteration, one item was deleted that had significant cross-loadings, starting with the item with the lowest absolute factor loading. After this, the EFA was rerun. Over all the EFA iterations, a total of 7 items were deleted. For an in-depth overview of results per EFA-iteration, see Supplementary Materials. This iterative process resulted in a final EFA model with a 2-factor structure and acceptable model fit (TLI = 0.858; RSMEA = 0.059 [0.037–0.080]). Factor 1 presents items concerning social prosocial risk-taking and is comprised of 8 items loading between 0.335–0.695. Factor 2 presents items concerning material prosocial risk-taking and is comprised of 4 items loading between 0.395–0.667. The two factors together accounted for 27% of the variance.

Confirmatory factor analyses

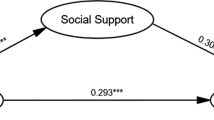

To validate the factor structure proposed by the final EFA model, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed with this final model as input. When studying the CFA output, it was found that one item in factor 2 had insufficient factor loadings (0.222). This item was therefore removed from the factor and CFA was rerun. After this deletion, factor 2 only contained three items. The original item list was checked to see if, based on theoretical fit, an item could be added to increase test length. With excellent theoretical fit, one item was added to factor 2 and CFA was rerun. This 2-factor model achieved an acceptable model fit (SRMR = 0.065 (good fit < 0.08); RMSEA = 0.066 [0.053–0.079] (good fit < 0.06 and adequate fit < 0.08); CFI = 0.801 (adequate fit > 0.90); TLI = 0.753 (adequate fit > 0.90)). Final CFA resulted in all factor loadings > 0.3, ranging from 0.308–0.634 (mean = 0.449; SD = 0.10). The two validated factors, full description of the English items and final factor loadings are presented in Table 1. The standardized correlation between factor 1 (social prosocial risk-taking) and factor 2 (material prosocial risk-taking) is 0.61 (p < 0.001), indicating a significant correlation between the two factors. More information can be found in the html file with knitted R code, as can be found on the OSF project page: https://osf.io/w7hsf/. The complete Dutch questionnaire including scoring instructions can be found in Supplementary Materials.

To evaluate measurement invariance, a series of models were compared using the Chi-square (χ2) difference test. Each model was compared to a more constrained model to determine measurement invariance. The results indicate that the metric model holds (Δχ2 = 14.0, Δdf = 10, p = 0.173). This showed the construct is measured similarly across gender groups and mean scores can be compared. The scalar model does not hold (Δχ2 = 37.31, Δdf = 10, p < 0.001), indicating that some item intercepts differ systematically across groups. This suggests potential measurement bias, meaning that one gender group tends to score higher or lower on certain items independent of the latent trait being measured.

Reliability

Internal consistency was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha values for the PAR-Q as a whole and for the subscales separately. For the whole questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (α = 0.69). For the Social subscale, Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.63, for the Material subscale Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.59. An alternative to Cronbach’s alpha, McDonalds Omega35 was calculated and was indicative of acceptable reliability (ωt = 0.74)35,36. To assess test–retest reliability a subset of the participants filled in the PAR-Q again after six weeks. Intraclass correlations were calculated using these data points. The average raters absolute ICC value for the whole questionnaire was 0.895 (F(356,357) = 9.528; p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.871–0.915]). For the Social subscale, average raters absolute ICC value was 0.802 (F(356,357) = 5.045; p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.756–0.839]). For the Material subscale, average raters absolute ICC value was 0.866 (F(356,357) = 7.467; p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.836–0.892]). These values indicate excellent stability of the questionnaire over time.

Convergent validity

The convergent validity of PAR-Q, prosociality, prosocial tendencies and cognitive and affective empathy was assessed by Pearson correlations (see Table 2). As expected, prosociality correlated positively with prosocial risk-taking behavior (‘prosocial’ subscale of the SDQ: r = 0.44; t(353) = 9.170; p < 0.001; PMT-R: r = 0.20; t(355) = 3.849; p < 0.001). Furthermore, as expected prosocial risk-taking was positively correlated with affective empathy (r = 0.33; t(355) = 6.624; p < 0.001) and cognitive empathy (r = 0.29; t(355) = 5.642; p < 0.001).

Additional exploratory analyses were performed to investigate how impulsivity, sensation seeking, and risk-taking are related to prosocial risk-taking. Results indicated no significant correlation between prosocial risk-taking and sensation seeking (r = − 0.07; t(355) = − 1.312; p = 0.190) and a significant negative correlation with risk-taking behavior (r = − 0.14; t(355) = − 2.661; p = 0.008) and impulsivity (r = − 0.28; t(355) = − 5.565; p < 0.001).

Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity of PAR-Q and resilience was measured by Pearson correlations. This was done in a subset of the EFA sample, as no unrelated measure to assess discriminant validity was included in the data collection for the sample 2. This subset of the EFA sample consisted of 134 adolescents (83 girls) aged 14–17 (Mage = 16.35; SD = 1.09). Analysis revealed no significant correlation between prosocial risk-taking as measured by PAR-Q and resilience (r = 0.00; t(132) = − 0.053; p = 0.958). Despite its limitations, these results support discriminant validity of the PAR-Q.

Discussion

Recently, the field of prosocial risk-taking behavior gained more research attention. More knowledge on prosocial risk-taking behavior and gaining more insights in what factors influence this behavior, could add to the positive development of adolescents. However, availability of validated measurement tools is still limited, precluding thorough investigation of prosocial risk-taking behavior. The goal of this research was to develop and validate an inclusive, multifaceted measure that assesses prosocial risk-taking in adolescents. Based on an EFA and CFA two subscales a measure with a total of 12 items divided over two subscales was identified. The PAR-Q is a multifaceted and diverse questionnaire with a strong theoretical factor structure, acceptable psychometric properties and excellent test–retest reliability. The PAR-Q provides an opportunity to help gain more knowledge about the theoretical position of prosocial risk-taking behavior in risk-taking literature and how it bridges the field with prosocial research.

The two-factor structure resulting from the EFA and confirmed with the CFA represents two theoretical subscales: Social and Material prosocial risk-taking. The Social subscale seems to have strong prosocial and empathic underpinnings, whereas additionally, the Material subscale is also negatively related to risk-taking behavior. In the pre-validation questionnaire, items describing health and safety risks were also included, but these risks were not identified as a separate factor. These results indicate that these items are not a coherent, theoretically meaningful construct as constructed in this way. This is in contrast with negative risk-taking, where health and safety risks are an important ___domain37,38. Relevant to note is that more than half of the items constructed as health and safety risks, were excluded because of low KMO values. This suggests that these items were not adequate for factor analysis. One of the possible explanations for this, is that there might be big differences in how one would act in a health or safety risk situation depending on age or gender, influencing the answer patterns. This could indicate that there might be more individual differences in how adolescents approach taking health or safety risks for someone else (prosocial risk-taking) than in taking health and safety risks for themselves (negative or anti-social risk-taking).

Additionally, items involving known and unknown others were constructed in the pre-validated 29 item questionnaire. It was thought that social context could have a great influence on the decision-making process27,28. However, the factor analysis did not identify separate factors for known and unknown others. The questionnaire was constructed in such a way that all types of risks had vignettes with both known and unknown people. The factor analyses did identify different factors for different types of risks, which suggests that type of risks might be more pronounced than social context in prosocial risk-taking.

The questionnaire and its subscales showed acceptable internal consistency. Lower Cronbach’s alpha values are not surprising, since our goal was to estimate different facets and domains of prosocial risk-taking behavior. Internal consistency indicates how well the items of each scale measure the same construct. The items of the PAR-Q are constructed to incorporate different facets of prosocial risk-taking behavior, as demonstrated by the two-factor structure that distinguishes social and material prosocial risk-taking behavior. On top of this, the items in the questionnaire cover a large variety of situations (school, sports club, public places) and a variety of different contexts (involving friends, classmates, unknown people and online). The diversity in items, over the span of the dimensionality of prosocial risk-taking, resulted in an acceptable internal consistency. While the factor structure is comparable across genders, differences in mean scores should be interpreted with caution due to lack of scalar invariance. Test–retest reliability, assessed in a subset of the validation sample, was excellent. This indicates that the PAR-Q provides a stable and reproducible score for prosocial risk-taking behavior. Convergent validity was assessed by testing correlational patterns with external related measures. As expected, prosociality, prosocial tendencies and both affective and cognitive empathy were all positively correlated with prosocial risk-taking behavior as measured with the PAR-Q. These factors indicate the strong prosocial nature underlying prosocial risk-taking.

Exploratory analyses were performed to investigate how impulsivity, sensation seeking and risk-taking were related to prosocial risk-taking. Results showed that impulsivity and risk-taking were negatively correlated with prosocial risk-taking and sensation seeking was not significantly correlated with prosocial risk-taking behavior.

A theoretical model proposed by Do et al.5 suggests that prosocial risk-taking is at the intersection of prosocial and risk-taking behavior. The authors propose a two-axis model resulting in four quadrants. According to this model, prosocial risk takers fall in the quadrant high prosociality, high risk-taking. The current results provide evidence for the prosociality axis, but less so for the risk-taking axis.

As proposed in the introduction, this might be evidence that prosocial risk-taking behavior could be a variation of prosocial behavior, rather than of risk-taking behavior. The negative correlations we found between prosocial risk-taking and both risk-taking and impulsivity may suggest that prosocial risk-taking behavior can be a very deliberate decision. This is consistent with literature on prosocial behavior. The PAR-Q may capture especially reasoned rather than impulsive forms of prosocial risk-taking behavior. It could also be the case that in prosocial risk-taking, the prosocial element is the main driver of action while the risks associated with it are of lesser importance. This could be driven by a high sense of morality and drive to help another individual, regardless of the risks. In turn, this could explain the lack of significant correlation (either positive or negative) with sensation seeking. At least in some individuals, the risks might be considered with the purpose to help another individual, not from a thrill-seeking motive. Morality could be a strong predictor for prosocial risk-taking behavior and future research is encouraged. It is also possible that by constructing the items, risks were formulated as such that they were quite acceptable, or in other words, were not perceived as big risks by the participants. In that case, you are investigating how willing participants are to do things for someone else, rather than their willingness to take risks. Future research should further investigate factors underlying the decision making of prosocial risk-taking.

Our study has several strengths, a preregistered and rigorous methodology, two separate data sets for questionnaire validation and established internal consistency, convergent validity and test–retest reliability. However, a limitation of our study is the incomplete assessment of discriminant validity. Ideally, discriminant validity should be evaluated by including a theoretically unrelated construct to the data collection in order to demonstrate that the questionnaire does not measure unrelated concepts. Unfortunately, we did not include such a measure in the second sample, where we did include measures to establish convergent validity. However, to partially address this limitation, we utilized a subset of the first sample that was part of a larger data collection. This data collection included a measure for resilience, a construct theoretically distinct from prosocial risk-taking, that provides the opportunity to assess discriminant validity. Indeed, results indicated distinctiveness between resilience and prosocial risk-taking behavior as measured by the PAR-Q. Future research should aim to replicate our findings, ideally by incorporating predefined unrelated constructs during the design phase. Despite this limitation, these findings contribute to the initial evidence supporting the validity of the PAR-Q.

The current study presents a well-validated questionnaire to assess prosocial risk-taking behavior. The PAR-Q is validated for adolescents between the ages of 14–17 enrolled in high school as some items are situated in a high school environment. To broaden the scope of the measure and to facilitate research on developmental patterns of prosocial risk-taking, future research should focus on developing and validating prosocial risk-taking questionnaires for children under 14 and young adults (18 +). To ensure usability in children or young adults, items should be reviewed for (small) adjustment to match their daily life experiences. Furthermore, the current version of the questionnaire is validated in Dutch. Some items contain typical Dutch elements that are a vital aspect of Dutch adolescents’ daily life, such as riding a bike to school. Researchers are encouraged to work together on a suitable translation of the PAR-Q in their own language and future work should validate the questionnaire for use in different languages. An interesting future direction would be to test whether and in what way cultural norms affect prosocial risk-taking. Different cultural norms, manners and school systems can make decision making surrounding prosocial risk-taking and the possible risks resulting from the behavior quite different. Therefore, more research on possible cultural differences in prosocial risk-taking behavior is strongly encouraged.

With the new, validated PAR-Q, the tool box to investigate prosocial risk-taking is extended and better equipped to investigate existing questions in adolescent development. Apart from the theoretical framework suggested by Do et al.5 and a recent literature review39, no empirical research known to the authors was conducted to infer what characteristics or what combination of characteristics could predict prosocial risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Besides this, prosocial risk-taking behavior could also be influenced by cultural differences. Different cultural norms, manners and school systems can make decision making surrounding prosocial risk-taking and the possible risks resulting from the behavior quite different. More research on possible cultural differences in prosocial risk-taking behavior is strongly encouraged. Finally, more knowledge on the prosocial decision-making process of adolescents could help stimulate taking prosocial risks over negative risks in a younger generation with beneficial results for society as a whole.

Methods

This study was preregistered as “Development and Validation of the Prosocial Adolescent Risk-taking Questionnaire (PAR-Q)” on https://osf.io/k5d8b. All preregistered procedures were followed. Non-preregistered analyses are considered exploratory and reported as such. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All data presented in this manuscript was part of larger studies. Data, code and materials available via OSF project page: https://osf.io/w7hsf/

Scale development

Questionnaire construction consisted of several steps (see Fig. 1). First, a pilot version of the questionnaire was designed to test responses to each of the items and assess variation in responses among participants. The items for the pilot questionnaire were constructed by the authors and based on existing literature on prosocial risk-taking5,11,40 supplemented by examples of prosocial risk-taking behavior in adolescent daily life. Items were formulated as short statements (‘Standing up for someone being bullied’). The pilot questionnaire consisted of 13-items with answer scale from 0 to 100 to detect skewed answer patterns. In addition to the rating, participants provided a narrative response to reflect their considerations for rating the items. Pilot data were collected in 152 adolescents (71 girls) aged 13–19 (Mage = 17.45, SD = 1.03). Pilot data was collected as part of two bigger data collections (VCWE-2021-064R1 and VCWE-S-21-00,073) and recruited in the social circles of undergraduate students, using social media and guest lectures in high schools in the greater Amsterdam area as part of a larger fMRI study.

Based on the results of the pilot data, items for the pre-validation version of the PAR-Q were created by the authors. Six major changes were implemented. Firstly, items were constructed reflecting a wider range of prosocial risks, including social, reputational, health/safety and financial/material risks. Secondly, to assess the influence of social relations in prosocial risk-taking, items involving known people (friends, classmates, family) and unknown people were constructed. Thirdly, additional information was added to the items to minimize differences in interpretation. As participants indicated that they had different interpretations of the risks involved in a choice, text was added to explicitly state the risk of each statement. To encompass all information relevant to create such a story-like and diverse set of items, items were formulated as short stories (vignettes) instead of statements. Fourthly, changes were made to increase the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. After adding risks in four different domains (social, reputational, health/safety and financial/material) and the two social relations (known/unknown) the questionnaire consisted of six potential factors. As factors are recommended to have at least three items41, the authors supplemented the number of items to a total of 29 items, with multiple items per risk/social context. Fifthly, some of the items were rephrased to adhere to a reverse-coded pattern. Instead of an action to which the participant responds how likely they are to do the same, the reverse coded vignette describes not acting, and how likely it is that the participant would do the same. Lastly, the answering scale was changed to a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘Very unlikely’ to 7 ‘Very likely’.

After developing the pre-validation questionnaire, the authors carefully reviewed each vignette to ensure it was appropriate for the targeted age range. Given the specific nature of the vignettes, it was determined that they are most suitable for high school adolescents aged 14 to 17 years. As a final step in the questionnaire development, focus groups were organized to test whether item content was and formulation were clear and age-appropriate. The questionnaire was tested using multiple focus groups with a total of 6 adolescents (3 girls, 3 boys). Each adolescent completed the Prosocial Adolescent Risk-taking Questionnaire and was asked if the vignettes were clearly formulated, if the situations were recognizable, and if the language was appropriate for their age. Based on their feedback, some items were altered or fine-tuned.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited via social media and by undergraduate students from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Utrecht University as part of two larger data collections. The inclusion criteria were a signed consent from participants (and from parents if the participants were younger than 16), attendance to Dutch high school and mastery of the Dutch language. Participants in undergrad data collection participated with one of their parents and parental consent was obtained together with parents’ own consent. To obtain parental consent during online data collection, participants younger than 16 were asked to fill in the email address of one of their parents/caregivers. To this email address, a separate email with parental information for the study including a parental consent link was sent. Several automatic and manual checks were implemented to ensure with large certainty that participants’ parents or caregivers signed parental consent before participants received the link to the questionnaires. If there was any suspicion this was not the case, participants did not receive the link to the questionnaires. Participants could withdraw from participation at any moment, without giving a reason. The research protocol for the data collection at the Vrije Universiteit is approved by the VCWE (Vaste Commissie Wetenschap en Ethiek) of the Faculty of Movement and Behavioural Science of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VCWE-2023–030, VCWE-S-2022–00,132). The research protocol for the data collection at the Utrecht University is approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences of the Utrecht University (FERB-23-0033).

For an exploratory factor analysis, a minimal sample size of 200 participants is recommended42. The aim was to include between 200 and 250 participants for the EFA. A total of 546 participants started the online questionnaire. After data cleaning, 234 data samples remained in sample 1. Online data collection generally has a higher percentage of unusable data sets43. In sample 1, datasets were removed for various reasons: participants did not start the PAR-Q or filled in only 50% of the PAR-Q, double entries by single participants, data quality doubts, missing date of birth, participants were not enrolled in high school or either too young or too old. Questionnaires were programmed in such a way that all items required a response. This means that if participants finished the questionnaire, there are no missing values. Unfinished datasets were preregistered to not be used as valid entries. This resulted in no missing data for the PAR-Q in the EFA sample.

The final sample used for the EFA consisted of 234 adolescents (149 girls). Participants could self-identify as ‘girl’, ‘boy’ or ‘other’, one participant identified as ‘other’. Participants were aged between 14 and 17 (Mage = 16.40, SD = 1.06) and were all enrolled in high school in the Netherlands. Most of the participants were enrolled in the highest level of Dutch high school education (n = 124; 53.0%). A total of 65 participants was enrolled in medium-level education (n = 65; 27.8%), and 29 participants were enrolled in a lower-level education (n = 29, 12.4%). A few participants were in a bridging level class, either low/medium (n = 10, 4.3%) or medium/higher (n = 5, 2.1%). One participant indicated that they were enrolled in high school, but information on level of education was missing.

Data analysis

Data inspection

Data were screened for multivariate outliers using Mahalanobis distance. Twenty-seven cases were identified as multivariate outliers. As thorough data quality control was already performed, the multivariate outliers were reviewed to detect problematic answer patterns (i.e., all items with the same answer). Each of the identified outliers were reviewed. As all answer patterns seemed valid, these cases were not removed.

Univariate normality was checked by measuring skewness and kurtosis. All skewness and kurtosis values were less than |2.0|, except for one item which had a kurtosis value of 2.35, which is indicative of slight non-normality. In general, data was considered univariate normal. Multivariate normality as tested by Mardia’s skewness and kurtosis tests suggest that data are considered multivariate non-normal (psych package in R44). It was therefore concluded that analyses should be adjusted to accommodate (slight) non-normality by choosing robust methods.

Linearity was checked by inspecting residual plots, indicating linearity between items. Multicollinearity was checked by examining the pattern of inter-item-correlations in a correlation matrix. Correlations of above 0.90 as well as multiple inter-item-correlations of above 0.70 can be indicative of multicollinearity. All inter-item-correlations were ≤ 0.56, indicative of slight multicollinearity between items. No items were removed based on these inter-item-correlations.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests were used to evaluate whether the data were suitable for factor analysis45. The Bartlett’s test was performed using Rstudio46, version 2023.03.0. The Bartlett’s test suggests there is sufficient significant correlation in the data for factor analysis (χ2 (406) = 1289.98, p < 0.001). The KMO test was performed using the psych package in R44. KMO factor adequacy values of 0.70 and above indicate data is suitable for performing factor analyses47,48. Overall Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin factor adequacy was 0.73. Ten items had KMO values < 0.7, indicative of (mild) factor inadequacy. These ten items were not included in the EFA iterations. The complete list of items with KMO values can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Exploratory factor analysis

The EFA was performed using the psych package in R44. The EFA consists of two phases, factor retention (identifying the number of factors) and factor rotation (identifying which items load onto which factors and how strongly). Considering the slightly non-normal nature of the data, the robust maximum-likelihood (MLR) factor extraction method was used in both the factor retention and the factor rotation. In factor retention, the final factor structure was determined based on a parallel analysis and a visual scree plot (for recommendations concerning factor structure determination, see ref.49,50,51). In factor rotation, oblique rotations (direct quartimin; oblimin) were used as factor rotation method, as some correlation among factors was expected.

During factor retention, visual scree plot and parallel analysis gave an indication of the ideal number of factors. The number suggested during the factor retention was also used as input during the factor rotation phase. As literature suggests49,52 multiple exploratory factor analyses with different number of factors extracted (one below and one above the suggested number of factors) can also be performed to find best model fit. In the factor rotation phase the final factor structure selection is based on model fit, item loadings and theoretical cohesion. Model fit was acceptable for root mean square of (RMSEA) values of 0.08 or lower and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) values of 0.90 and above53,54,55. In an iterative process, items with insufficient factor loadings and high cross-loadings were deleted to reach a final model. Per iteration, one item was deleted based on predefined conditions. First, the item loadings were checked for items with loading < 0.3, where the lowest item loading was deleted and the EFA was rerun. When all items loaded > 0.3, cross-loadings were examined. Per iteration, one item was deleted that had significant cross-loadings, starting with the item with the lowest absolute factor loading. After this, the EFA was rerun.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Construct Validation

Participants and procedure

To perform the confirmatory factor analysis and analyses for reliability and convergent validity we collected a new sample. We preregistered to include a minimal sample size of 300 adolescents. This is based on the 10:1 (participants-to-items) ratio recommendation from Bentler and Chou56, as the original, pre-validation version of the questionnaire consisted of 29 items. Additionally, for a CFA it is important that the number of knowns (the elements in the input matrix) is higher than the number of unknowns (freely estimated parameters57). For the 12-item questionnaire that was tested here, with 78 knowns to 25 unknowns, this was the case.

Participants were recruited via guest lectures at high schools and via social media, using an informative social media channel targeted at high school aged adolescents. Additionally, at the end of the questionnaire, the participants were asked to send the questionnaire forward to peers, based on the snowball sampling principle. The inclusion criteria were signed informed consent from participant (and from parent/caregiver if participant was younger than 16 years old), participant should master the Dutch language, should be aged 14 years or older to participate and should be enrolled in high school. Following the set exclusion criteria, individuals could not participate if they were not enrolled in high school at the moment of participation and individuals that were younger than 14 and older than 17 years old could not participate. Participants were informed they were going to fill in questionnaires about how they make choices, take risks and help each other. They first completed the online informed consent form. For participants aged 16 and above, participants could start the questionnaire after giving informed consent. For participants aged 14 and 15, additional parental informed consent was collected, by asking to fill in the email address of one of their parents/caregivers. To this email address, a separate email with parental information for the study including a parental consent link was sent. Several automatic and manual checks were implemented to ensure with large certainty that participants’ parents or caregivers signed parental consent before participants received the link to the questionnaires. Only after this parental informed consent was received, underaged participants could start with the questionnaire. If there was any suspicion this was not the case, participants did not receive the link to the questionnaires. Participants could withdraw from participation at any moment, without giving a reason. The research protocol for the validation of the Prosocial Adolescent Risk-taking Questionnaire was approved by the VCWE (Vaste Commissie Wetenschap en Ethiek) of the Faculty of Movement and Behavioral Science of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VCWE-S-2022–00,132). Filling in all questionnaires in this data collection took the participants around 60 min. This data collection included more questionnaires than presented in this manuscript. In the debriefing they were informed about the real goal of the study and got information about the concept of prosocial risk-taking. They received contact information from the researchers to ask additional questions. Finally, after finishing the questionnaires, participants were given the opportunity to fill in their bank account information so they could receive their 10-euro reimbursement.

A total of 482 participants started the online questionnaire. After data cleaning, 357 data samples remained in sample 2. In sample 2, datasets were removed for various reasons: participants did not start the PAR-Q or filled in only 50% of the PAR-Q, missing (parent/caregiver) consent, double entries by single participants, incomplete entries (added to sample 1, as preregistered), duration of total questionnaire under preregistered 500 s, missing date of birth, participants were not enrolled in high school or either too young or too old. Questionnaires were programmed in such a way that all items required a response. This means that if participants finished the PAR-Q, there are no missing values for this questionnaire. Incomplete entries of the entire test battery, but with complete PAR-Q, were preregistered to be added to the EFA sample. Incomplete PAR-Q entries in the CFA sample were not usable for the EFA and therefore not included in the EFA sample. This resulted in no missing data for the PAR-Q in the CFA sample.

The final sample used for the CFA consisted of 357 participants, 208 girls. Participants were aged between 14 and 17 (Mage = 16.06, SD = 1.12) and enrolled in high school in the Netherlands. Most of the participants were enrolled in the highest level of Dutch high school education (n = 231; 64.7%). A total of 84 participants was enrolled in medium-level education (n = 84, 23.5%), and 18 participants were enrolled in a lower-level education (n = 18, 5.0%). A few participants were enrolled in a bridging level class, either low/medium (n = 11, 3.1%) or medium/higher (n = 13, 3.6%). Participants could self-identity as ‘girl’, ‘boy’ or ‘other’, three identify as ‘other’. Of the participants, 80 participants had one or both of parent(s) not born in the Netherlands (22.4%). Parents were born in wide variety of European, African, Central American, Middle Eastern or Asian countries. A total of 57 (16%) participants identified themselves with a different nationality than Dutch or a combination of Dutch and a different nationality. Fifty-one cases were identified as multivariate outliers. As thorough data quality control was already performed, the multivariate outliers were reviewed to detect problematic answer patterns (i.e., all items with the same answer). All individual multivariate outlier cases were reviewed and since answer patterns seemed valid, it was decided not to remove these participants from the sample, resulting in the final sample size of 357 participants for the confirmatory factor analysis. The final 12-item version of the questionnaire approaches a 30:1 participants-to-items ratio (aim was 10:156), indicating that this sample size is sufficient to validate PAR-Q using CFA.

To assess test–retest reliability we preregistered to collect a total of 50 datasets. All participants were asked whether they would be interested in filling in a test–retest six weeks after participation. If they were interested, they filled in their email address. After six weeks, they received a personalized link to the test–retest questionnaire. Test–retest data collection consisted of basic demographics and the Prosocial Adolescent Risk-taking Questionnaire. A total of 72 participants (36 girls, Mage = 15.68; SD = 0.99) filled in the questionnaire for the second time. The time between the two measurements ranged from 40 to 70 days (Mdays = 47.10; SD = 6.07).

Data analysis

The lavaan package in R58 was used to perform the CFA on the 12-item PAR-Q that resulted from the EFA. Maximum-likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used, as the CFA data was also considered slightly non-normal. Robust model fit indices were reported. Multiple model fit indices were reported to indicate model fit. The following cut-off values were used: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were considered good at ≥ 0.95 and adequate at ≥ 0.9059,60, for Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 is considered adequate model fit61, and < 0.06 good model fit62. For Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) scores below 0.08 indicate good model fit63. On top of model fit, individual item factor loadings were checked. If item loading is insufficient, an item could be up for removal. Based on theoretical considerations, items could be added to increase model fit. Removal or addition of items happened in an iterative process.

Analyses to assess measurement invariance were not preregistered, so should be considered exploratory. To assess measurement invariance, we performed metric invariance (restricting factor loadings) and scalar invariance (restricting factor loadings and intercepts) CFA models and compared them to the baseline, configural CFA model. To evaluate measurement invariance, we compared the different models using the Chi-square (χ2) different test. Non-significant Chi-square tests support measurement invariance.

Internal consistency was assessed for all items and the different subscales separately. As preregistered, this was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Exploratively, internal consistency was also assessed by McDonald’s Omega (total score). Convergent validity was investigated by testing the Pearson correlational patterns between PAR-Q and other related measures. PAR-Q total scores and scores for factor one and factor two were correlated with prosocial tendencies (PTM-R), prosocial behavior (SDQ prosocial), cognitive empathy (IRI Perspective Taking) and affective empathy (IRI Empathic Concern). Pearson’s correlations were computed to assess how the concepts of impulsivity, sensation seeking and risk-taking behavior are related to prosocial risk-taking behavior. Test–retest reliability of the PAR-Q was assessed using interclass correlations (ICCs).

Analyses to assess discriminant validity were not preregistered and hypothesized a priori, so should be considered exploratory. No theoretically unrelated measure to assess discriminant validity was included in our sample 2 data collection. Some of the sample 1 data was collected as a part of bigger data collections and sample 1 included the theoretically distinct construct ‘resilience’ as measured by the Brief Resilience Scale64. This measure was available in a sample of N = 134 participants (83 girls) aged 14–17 years old (Mage = 16.35; SD = 1.09). Similar to our analysis to assess convergent validity, we assess the discriminant validity with Pearson’s correlations. Correlations were computed between prosocial risk-taking as measured by the PAR-Q and the theoretically unrelated construct resilience as measured by the Brief Resilience Scale64.

Measures

Demographics

Information about school grade and education, country of birth from parents and ethical identity were gathered.

Prosocial behavior

Prosocial behavior was measured using the Prosocial subscale of the Dutch translation of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ29). The Prosocial subscale consists of 5 items (e.g., ‘I try to be nice to other people. I care about their feelings.’). Items are rated on a 3-point scale, 0 ‘Untrue’, 1 ‘A bit true’ and 2 ‘Very true’, according to how well each item describes them. Ratings from the 5 items were summed to calculate a total score for prosocial behavior. Total scores range from 0 to 10. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale has been reported as α = 0.6365. In the current sample, the SDQ prosocial subscale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65.

Prosocial tendencies

Prosocial tendencies were measured using the Dutch translation of the Prosocial Tendencies Measure – Revised (PTM-R30). The PTM-R consists of 25 items. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘Does not describe me at all’ to 5 ‘Describes me very well’. The PTM-R has six subscales, Altruism (e.g., ‘I often help even if I don’t think I will get anything out of helping’), Anonymous (e.g., ‘I think that helping others without them knowing is the best type of situation’), Public (e.g., ‘I can help others best when people are watching me’), Emotional (e.g., ‘I respond to helping others best when the situation is highly emotional’), Dire (e.g., ‘I tend to help people who are in real crisis or need’) and Compliant (e.g., ‘When people ask me to help them, I don’t hesitate’). Ratings from the 25 items were summed to calculate a total score for prosocial tendencies. Total scores could range from 25 to 125. Cronbach’s alpha for the PTM-R has been reported to range between α = 0.75 and α = 0.8630. In the current sample, the PTM-R has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

Cognitive empathy

Cognitive empathy was measured using the Perspective Taking subscale of the Dutch translation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index31,66. The Perspective Taking subscale consists of 7 items (e.g., ‘I believe that there are two sides to every question and try to look at them both.’). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 ‘Does not describe me very well’ to 4 ‘Describes me very well’. After recoding two items, ratings from the seven items were summed to calculate a total score for cognitive empathy. Total scores could range from 0 to 28. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale has been reported as α = 0.7366. In the current sample, the IRI cognitive empathy subscale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70.

Affective empathy

Affective empathy was measured using the Empathic Concern subscale of the Dutch translation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index31,66. The Empathic Concern subscale consists of 7 items (e.g., ‘I am often quite touched by things that I see happen.’). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 ‘Does not describe me very well’ to 4 ‘Describes me very well’. After recoding three items, ratings from the seven items were summed to calculate a total score for affective empathy. Total scores could range from 0 to 28. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale has been reported as α = 0.7366. In the current sample, the IRI affective empathy subscale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74.

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was measured using the Dutch translation of the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS-1132). The BIS-11 consists of 30 items (e.g., ‘I do things without thinking.’). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘Seldom/never’ to 4 ‘Almost always’. The BIS-11 has three subscales, Cognitive, Motor and Non-planning Impulsivity. After recoding nine items, ratings from the 30 items were summed to calculate a total score for impulsivity. Total scores range could from 30 to 120. Cronbach’s alpha for the BIS-11 has been reported as α = 0.7467. In the current sample, the BIS-11 has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79.

Sensation seeking

Sensation seeking behavior was measured using the Sensation Seeking subscale of the Dutch Scale for Proneness to Boredom (NSGV33). The Sensation Seeking subscale consists of 5 items (e.g., ‘I only feel alive when I do something exciting.’). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘That is surely not the case’ to 7 ‘That is surely the case’, according to how well each item describes them. Ratings from the five items were summed to calculate a total score for sensation seeking. Total scores could range from 5 to 35. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale has been reported as 0.7133. In the current sample, the sensation seeking subscale of the NSGV has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.63.

Risk-taking behavior

Likelihood of risk-taking behavior was measured using the Likelihood subscale of the adolescent version of the Domain-Specific Risk-Taking scale, based on the adult version (DOSPERT24,34). The original adolescent DOSPERT consists of 39 items, but the commonly used Dutch version consists of 38 items37. In this research, the 38-item is used. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘Extremely unlikely’ to 7 ‘Extremely likely’. Items are divided over five subscales, representing Health/Safety (e.g., ‘Drinking at a party’), Recreational (e.g., ‘Going down a ski run that is beyond your ability’), Ethical (e.g., ‘Telling your friend a lie’), Social (e.g., ‘Speaking out against a popular opinion at school’) and Financial (e.g., ‘Betting all your pocket money on the outcome of a sporting event’) risks. Ratings from the 38 items were summed to calculate a total score for likelihood of risk-taking behavior. Total scores could range from 38 to 266. Cronbach’s alpha for the risk-taking likelihood has been reported to range between α = 0.59 and α = 0.8237. In the current sample, the DOSPERT likelihood scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88.

Resilience

Resilience was measured using the Dutch translation of the Brief Resilience Scale64. The BRS consists of 6 items (e.g., ‘I usually come through difficult times with little trouble.’). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘Completely disagree’ to 7 ‘Complete agree’, according to how much participants agree with the statement presented. Items 2, 4, and 6 needed to be recoded. After recoding, ratings from the six items were summed to calculate a total score for resilience. Total scores could range from 6 to 30. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale has been reported as 0.8564. In the current sample, the BRS has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80.

Prosocial risk-taking behavior

Prosocial risk-taking behavior was measured using the newly developed Prosocial Adolescent Risk-taking Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Participants were asked “You are going to read about a number of situations you might find yourself in. In doing so, you will also read about how you may react in those situations. Try to imagine what it would be like if you found yourself in such a situation. For each situation, choose how likely it is that you would react as described.”. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘Very unlikely’ to 7 ‘Very likely’, according to how likely it is that the participant would act as is described in the vignette. The final version of the questionnaire in English (not validated yet) and Dutch with scoring instructions can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Data availability

Data access via download; usage of data restricted to scientific purposes (scientific use file). Code access via download; usage of data restricted to scientific purposes (scientific use file). Data and code available via OSF project page: https://osf.io/w7hsf/

References

Crone, E. A. & van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. Multiple pathways of risk taking in adolescence. Dev. Rev. 62, 100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100996 (2021).

Steinberg, L. Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16(2), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00475.x (2007).

Crone, E. A., van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. & Peper, J. S. Annual Research Review: Neural contributions to risk-taking in adolescence–developmental changes and individual differences. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57(3), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12502 (2016).

Duell, N. & Steinberg, L. Positive risk taking in adolescence. Child Dev. Perspect. 13(1), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12310 (2019).

Do, K. T., Moreira, J. F. G. & Telzer, E. H. But is helping you worth the risk? Defining prosocial risk taking in adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 25, 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.11.008 (2017).

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K. & Kaukiainen, A. Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggress. Behav. Offic. J. Int. Soc. Res. Aggress. 22(1), 1–15. (1996).

Lambe, L. J., Della Cioppa, V., Hong, I. K. & Craig, W. M. Standing up to bullying: A social ecological review of peer defending in offline and online contexts. Aggress. Violent. Beh. 45, 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.007 (2019).

Paciello, M., Fida, R., Tramontano, C., Cole, E. & Cerniglia, L. Moral dilemma in adolescence: The role of values, prosocial moral reasoning and moral disengagement in helping decision making. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 10(2), 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.759099 (2013).

Sierksma, J., Thijs, J., Verkuyten, M. & Komter, A. Children’s reasoning about the refusal to help: The role of need, costs, and social perspective taking. Child Dev. 85(3), 1134–1149. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12195 (2014).

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Memmott-Elison, M. K. & Nielson, M. G. Longitudinal change in high-cost prosocial behaviors of defending and including during the transition to adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 1853–1865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0875-9 (2018).

Armstrong-Carter, E., Do, K. T., Moreira, J. F. G., Prinstein, M. J. & Telzer, E. H. Examining a new prosocial risk-taking scale in a longitudinal sample of ethnically diverse adolescents. J. Adolesc. 93, 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.11.002 (2021).

Blankenstein, N. E., Telzer, E. H., Do, K. T., Van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. & Crone, E. A. Behavioral and neural pathways supporting the development of prosocial and risk-taking behavior across adolescence. Child Dev. 91(3), e665–e681. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13292 (2020).

Steinberg, L. A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Psychobiol. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Psychobiol. 52(3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20445 (2010).

Romer, D. Adolescent risk taking, impulsivity, and brain development: Implications for prevention. Dev. Psychobiol. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Psychobiol. 52(3), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20442 (2010).

Duell, N. & Steinberg, L. Differential correlates of positive and negative risk taking in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 49(6), 1162–1178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01237-7 (2020).

Wood, A. P., Dawe, S. & Gullo, M. J. The role of personality, family influences, and prosocial risk-taking behavior on substance use in early adolescence. J. Adolesc. 36(5), 871–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.003 (2013).

Patterson, M. W., Pivnick, L., Mann, F. D., Grotzinger, A. D., Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L. D., & Harden, K. P. Positive risk-taking: Mixed-methods validation of a self-report scale and evidence for genetic links to personality and negative risk-taking. Faculty/Researcher Works (2019). https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bq63f

Carlo, G., Crockett, L. J., Wolff, J. M. & Beal, S. J. The role of emotional reactivity, self-regulation, and puberty in adolescents’ prosocial behaviors. Soc. Dev. 21(4), 667–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00660.x (2012).

Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Pastorelli, C., Eisenberg, N., Zuffianò, A. & Caprara, G. V. The development of prosociality from adolescence to early adulthood: The role of effortful control. J. Pers. 81(3), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12001 (2013).

Eisenberg, N. & Spinrad, T. L. Multidimensionality of prosocial behavior. Prosocial Dev.: Multidimensional Approach 13, 17–39 (2014).

Eisenberg, N. & Miller, P. A. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 101(1), 91 (1987).

Eisenberg, N. & Fabes, R. A. Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motiv. Emot. 14(2), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991640 (1990).

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A. & Winiewski, M. Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of affective versus cognitive empathy in increasing prosocial cyberbystander behavior. Front. Psychol. 9, 799. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00799 (2018).

Blais, A. R. & Weber, E. U. A ___domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 1(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500000334 (2006).

Blakemore, S.-J. & Mills, K. L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing?. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1146/annu-rev-psych-010213-115202 (2014).

Brown, B. B. Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In Handbook of adolescent psychology 2nd edn (eds Lerner, R. M. & Steinberg, L.) 363–394 (Wiley, 2004).

Gardner, M. & Steinberg, L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Dev. Psychol. 41, 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625 (2005).

van Hoorn, J., Fuligni, A. J., Crone, E. A. & Galvan, A. Peer influence effects on risk-taking and prosocial decision-making in adolescence: Insights from neuroimaging studies. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 10, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.05.007 (2016).

Van Widenfelt, B. M., Goedhart, A. W., Treffers, P. D. & Goodman, R. Dutch version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 12, 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0341-3 (2003).

Carlo, G., Hausmann, A., Christiansen, S. & Randall, B. A. Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of prosocial tendencies for adolescents. J. Early Adolescence 23(1), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431602239132 (2003).

Davis, M. H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113 (1983).

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51, 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6%3c768::AID-JCLP2270510607%3e3.0.CO;2-1 (1995).

Zondag, H. Introductie van een Nederlandstalige Schaal voor Gevoeligheid voor verveling (nsgv). Psychologie en Gezondheid, jaargang 2007(35), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03071803 (2007).

Weber, E. U., Blais, A. R. & Betz, N. E. A ___domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 15(4), 263–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.414 (2002).

Hayes, A. F. & Coutts, J. J. Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. Commun. Methods Measures 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629 (2020).

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T. & Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046 (2014).

Blankenstein, N. E. et al. Adolescent risk-taking likelihood, risk perceptions, and benefit perceptions across domains. Personal. Individual Differ. 231, 112806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112806 (2024).

Willoughby, T., Heffer, T., Good, M. & Magnacca, C. Is adolescence a time of heightened risk taking? An overview of types of risk-taking behaviors across age groups. Dev. Rev. 61, 100980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100980 (2021).

Armstrong-Carter, E. & Telzer, E. H. The development of prosocial risk-taking behavior: Mechanisms and opportunities. Child Dev. Perspect. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12525 (2024).

Gross, J. et al. When helping is risky: The behavioral and neurobiological trade-off of social and risk preferences. Psychol. Sci. 32(11), 1842–1855. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211015942 (2021).

Leandre, R., Fabrigar, L. R. & Wegener, D. T. Exploratory factor analysis (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Howard, M. C. A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: What we are doing and how can we improve?. Int. J. Human-Comput. Interact. 32(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1087664 (2016).

Nayak, M. S. D. P. & Narayan, K. A. Strengths and weaknesses of online surveys. Technology 6(7), 0837–2405053138. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2405053138 (2019).

Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (Version 1.7.8), Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA (2017). Available from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych. Retrived February 24, 2019

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S. & Ullman, J. B. Using multivariate statistics Vol. 6, 497–516 (Pearson, 2013).

Rstudio Team (2020). Rstudio: Integrated Development for R. Rstudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/.

Kaiser, H. F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575 (1974).

Lloret, S., Ferreres, A., Hernández, A. & Tomás, I. The exploratory factor analysis of items: Guided analysis based on empirical data and software. Anales de psicología 33(2), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.270211 (2017).

Knekta, E., Runyon, C. & Eddy, S. One size doesn’t fit all: Using factor analysis to gather validity evidence when using surveys in your research. CBE Life Sci. Educat. 18(1), rm1. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-04-0064 (2019).

Luo, L., Arizmendi, C. & Gates, K. M. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) programs in R. Struct. Equ. Model. 26(5), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1615835 (2019).

Fabrigar, L. R. & Wegener, D. T. Exploratory factor analysis (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Costello, A. B. & Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 10(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868 (2005).

West, S. G., Taylor, A. B. & Wu, W. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. Handbook Struct. Equ. Model. 1(1), 209–231 (2012).

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T. & Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2 (2004).

Hopwood, C. J. & Donnellan, M. B. How should the internal structure of personality inventories be evaluated?. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 14, 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310361240 (2010).

Bentler, P. M. & Chou, C. P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Soc. Methods Res. 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004 (1987).

Brown, T. A. & Moore, M. T. Confirmatory factor analysis. Handbook Struct. Equat. Model. 361, 379 (2012).

Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Statist. Softw. 48, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02 (2012).

Bentler, P. M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 107, 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 (1990).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd Edn. Methodology in the Social Sciences. (New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2011).

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. & Young, S. L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149 (2018).

Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing structural equation models (eds Bollen, K. A. & Long, J. S.) 136–162 (Sage, 1993).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Smith, B. W. et al. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 15, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972 (2008).

Muris, P., Meesters, C. & van den Berg, F. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) further evidence for its reliability and validity in a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2 (2003).

De Corte, K. et al. Measuring empathic tendencies: Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Psychologica Belgica 47(4), 235–260. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-47-4-235 (2007).

Hartmann, A. S., Rief, W. & Hilbert, A. Psychometric properties of the German version of the Barratt impulsiveness scale, version 11 (Bis–11) for adolescents. Percept. Mot. Skills 112(2), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.2466/08.09.10.PMS.112.2.353-368 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the adolescents that participated in this study, the undergraduate students that helped with data collection, and the schools that welcomed us for giving guest lectures.

Funding

The research was funded with the support of the Ammodo Science Award 2020 for Social Sciences. The funders had no role in this study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR, PVL, BRB and LK developed the study concept. RR, PVL, BRB and LK were involved in study design. RR collected the data. RR carried out the analyses and wrote the initial draft of the paper. PVL, BRB and LK provided feedback on the draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Rijn, R., van Lange, P.A.M., Krabbendam, L. et al. Construction and validation of the prosocial adolescent risk-taking questionnaire (PAR-Q). Sci Rep 15, 21252 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06034-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06034-5