Abstract

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of self-collected urine and vaginal samples for the identification of precancerous cervical lesions in the referral population using high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) assays based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It was a prospective study carried out in China from June 2021 to March 2022. The vaginal and urine samples were collected and analyzed by using a newly developed specific hrHPV PCR test, and matched cervical samples were analyzed by using an approved hrHPV DNA test. The primary outcomes were sensitivity for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 or greater (CIN2 +). The secondary outcome was the accuracy of hrHPV findings in urine and vaginal samples compared to cervical samples. A total of 1,701 women were recruited with 113 women excluded. Among 1,588 qualified participants, a total of 203 cases of the CIN2 + group were enrolled in the two centers. The sensitivity and specificity of HPV detection for CIN2 + in urine, vaginal and cervical samples were 86.70% and 36.46%, 90.64% and 30.54%, 93.60% and 26.14%, respectively. The urine sample performed lower sensitivity (p = 0.003) and higher specificity (p < 0.001) than the cervical sample. There was no difference in sensitivity between vaginal and cervical samples (p = 0.146), and the specificity of vaginal samples was higher than that in cervical samples (p < 0.001). The agreement was 78.15% of urine and cervical samples and 85.71% of vaginal and cervical samples. HPV testing on self-collected urine and vaginal samples has acceptable consistency compared with traditional cervical samples. It may be an alternative option for cervical cancer screening. Additional studies are still required to substantiate this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the reported global statistics, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in terms of both incidence and mortality in women, with an estimated 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths worldwide in 2022, and the majority occurred disproportionately in transitioning countries1. The persistence of high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) infections has been extensively linked to the development of precancerous lesions and cervical cancer2. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends primary screening through the detection of hrHPV3, but low attendance rates associated with demographic and other factors can decrease the uptake of routine screening.

In China, the uptake of cervical cancer screening has been relatively low, with only an estimated 20–30% of eligible women participating in regular screening4. However, screening uptake represents much higher in developed countries with over 70%5. In many resource-limited areas of China, women may not have access to regular cervical cancer screening.

Recently, studies have shown that self-sampled HPV tests using urine or vaginal samples have accuracy comparable to conventional methods, providing an alternative option for cervical cancer screening. Despite this, the clinical outcomes across studies have varied greatly, and the accuracy of the tests may depend on the type of self-sampling assay. Additionally, limited data is available in China. Further research is needed to understand the optimal use of self-sampled assays for cervical cancer screening.

Consequently, the current study was conducted to evaluate the clinical performance of the newly developed PCR-based HPV DNA assay by using self-collected urine and vaginal samples and comparing results to the clinician-collected cervical samples by using approved DNA test.

Materials and methods

Study population

It was a prospective study carried out in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine and Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital from June 2021 to March 2022. Eligible participants were enrolled in the study referred to the colposcopy examination for one of the following indications: abnormal cytology results, infection with HPV-16/18, or persistent infection with other hrHPV subtypes. Inclusion criteria: (1) women aged 20–65 years; (2) sexually active. Exclusion criteria: (1) treated for cervical diseases before, including surgery, microwave or laser therapy; (2) suffering from acute gynecological inflammation, severe systemic diseases or other malignant tumors; (3) pregnant; (4) Participants unable to provide valid specimens or sufficient clinical information. Before enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the international standards based on the declaration of Helsinki.

Sample collection

The related pictographic instructions were provided for all individuals. Following the instructions for use of the CerviClear® (New Horizon Health Co., Ltd.) strictly before the pelvic examination, the participants collected at least 20 mL of first-void urine using a 50 ml centrifuge tube and then shake it 3–5 times to mix the urine sample with the preservation liquid. After urine sampling, the patients received a brush from MRC Technology for vaginal sampling and gently inserted the swab into the vagina to the top of the vaginal canal rotating it five times in a semi-sitting position, and then inserted the swab into the cell preservation tube, snapped it off and shaked it back 10–15 times up and down. Finally, the paired cervical sample was collected by a professional gynecologist who were blind to the outcomes of the urine test during the colposcopy. Suspicious lesions were sampled and endocervical curettage (ECC) were carried out for pathological biopsies after staining with 5% acetic acid. Samples were obtained from the four quadrants close to the squamo-columnar junction area if there were no suspicious lesions. After all samples were collected, they were promptly transshipped to the central laboratory of Hangzhou for processing.

Sample processing and laboratory analyses

The self-collected urine and vaginal samples were kept at room temperature and analyzed with CerviClear®, an HPV DNA-based assay developed by New Horizon Co., Ltd. which could separately genotype 14 hrHPV types including HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68 in a single test by targeting HPV L1 region. After being transported to the laboratory, the urine and vaginal samples were preserved with cell preservation solution under -20 °C before DNA extraction. The laboratory staff had no access to the clinical diagnostic data. During sample processing, 10 mL urine was transferred to a centrifuge tube, and 20μL magnetic beads were added. The samples were mixed for 10 s and centrifuged at 4000–5000 rpm for 3 min. After removing the supernatant, 300μL lysis buffer were added to the sample. For vaginal swabs, mix the vaginal swab sample evenly and transfer 1000μL to a centrifuge tube. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 1 min. Remove the supernatant and add 300μL lysis buffer, mix evenly for 10 s, and incubate at room temperature for 10 min before centrifuging again. Finally, cycle number values for three HPV signals (HPV16, HPV18, and other hrHPV) were reported. HPV DNA in cervical was purified using the kit from Tellgen Corporation Co., Ltd. The amplification of hrHPV DNA from urine and vaginal samples was undertaken by using CerviClear®, which was based on the ABI7500 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA). hrHPV DNA from cervical sample was analyzed with a hrHPV detection kit produced by Shanghai Tellgen Life Science Co. Ltd, which could also identify the 14 hrHPV types mentioned above.

Sample size considerations

The sample size of this study was determined mainly based on the method recommended in The Technical Guidelines for Clinical Trials of In Vitro Diagnostic Reagents. In this study, the expected sensitivity of urine/ vaginal HPV test classified CIN2 or greater (CIN2 +) was no less than 80%, the expected sensitivity could reach 85%. After calculation, at least 132 cases of histopathologically confirmed CIN2 + should be included in the two clinical institutions.

Reference clinical diagnosis

CIN2 + includes invasive cervical cancer, cancer in situ, CIN3, and CIN2 diagnosed by histopathology according to the 2020 WHO classification of the gynecological cervical tumor6. The following conditions can be diagnosed as < CIN2: (1) normal cytological and negative HPV result; (2) cytology ASCUS with negative HPV infection; (3) histopathological negative such as normal cervical epithelium, LSIL, inflammation.

Data analysis

The overall accuracy of HPV testing for the presence of HPV in urine, vaginal and cervical samples was calculated by HPV positive rate, agreement rate and kappa value. Agreement between the results of urine and cervical or vaginal and cervical samples was determined using Cohen’s kappa statistic. Agreement was slight (κ < 0.20), weak (κ = 0.21–0.40), moderate (κ = 0.41–0.60), substantial (κ = 0.61–0.80), near perfect (κ = 0.81–0.99) or perfect (κ = 1.00). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used to assess the clinical performance of paired urine and vaginal samples against cervical CIN2 + detection. CIN2 + was histologically confirmed, including CIN2, CIN3, cancer in situ, and invasive cervical cancer. McNemar’s test was used to determine the differences between paired samples. And the differences between groups were considered statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.05. All statistics were completed by SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corporation, New York).

Results

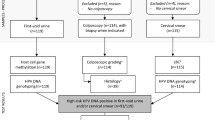

A total of 1,701 women were recruited with 113 women excluded due to inconformity of inclusion and exclusion criteria, unqualified samples, lack of clinical diagnosis reports, and invalid tests (Fig. 1).

Among 1,588 qualified participants, a total of 203 cases of CIN2 + group were enrolled in the two centers, including 12 cases of cervical cancer, 5 cases of AIS (adenocarcinoma in situ), 95 cases of CIN3, and 91 cases of CIN2. And 1385 cases of < CIN2 were included, including 332 cases of CIN1.

HPV agreement between paired samples

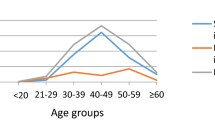

The consistency test showed that the agreement was 78.15% between urine and cervical sample(κ = 0.4708) and 85.71% between vaginal and cervical sample(κ = 0.6268). The agreement of urine vs cervical sample and vaginal vs cervical sample was moderate and substantial, respectively. There was a significant difference in hrHPV detection between self-collected samples and clinician-collected samples. The agreement between HPV tests in urine compared with cervical samples was lower than vaginal samples in every age group (Table 1).

Sensitivity and specificity for the detection of CIN2 + and CIN3 +

The sensitivity and specificity of HPV detection for CIN2 + in urine, vaginal and cervical samples were 86.70% and 36.46%, 90.64% and 30.54%, 93.60% and 26.14%, respectively. The urine sample performed lower sensitivity (p = 0.003) and higher specificity (p < 0.001) than the cervical sample. There was no difference in sensitivity between vaginal and cervical samples (p = 0.146), and the specificity showed significant difference (p < 0.001).

For CIN3 + detection, there was no difference in sensitivity between self-collected samples (urine vs cervical: p = 0.146; vaginal vs cervical: p = 1.000). And the specificity showed significant difference (urine vs cervical: p < 0.001; vaginal vs cervical: p < 0.001) (Table 2).

The agreement of HPV16/18 analysis

In the urine, vaginal and cervical samples, the prevalence of HPV 16 was 15.62%, 16.12% and 18.83%, respectively (Fig. 2). The overall agreement for HPV 16 was 92.25% (95%CI: 90.83–93.52) and 95.02% (95%CI: 93.84–96.04) between the paired urine and cervical samples and vaginal and cervical samples, respectively. And for HPV 18, the overall agreement was 94.21% (95%CI: 92.94–95.30) and 96.47%(95%CI: 95.44–97.36), respectively.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer deaths among women worldwide. Early detection and treatment of precancerous lesions (CIN2 +) is crucial in reducing the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer. Currently, cervical cytology and HPV DNA test are the most commonly used screening methods for cervical cancer. However, these methods have limitations, such as low participation rates, discomfort during sample collection, and the need for trained healthcare providers.

It has been proposed that self-collected urine and vaginal tests could be a feasible complement to the cervical cancer screening program since the potential use has been explored to evaluate the test accuracy of precancerous lesions detection7,8. Urine voiding in the first part (first-void urine) usually contains exfoliated cells of the debris and mucus from the female genital organs and cervix, i.e., the first-void urine contains higher concentrations of HPV DNA than midstream urine. According to this theory, the identification of biomarkers in first-void urine, as well as HPV DNA, can be used to screen for (pre)cervical cancer9. But the frequent barriers to application in self-sampling assays were attributed to the significant heterogeneity among studies, due to the methodology, preservation, and extraction of DNA. Thus, the accuracy of self-collected samples for detecting CIN2 + compared to clinician-collected cervical samples is still a matter of debate.

Several studies have been conducted to assess the possibility of self-collected urine samples for detecting CIN2 + and CIN3 + . A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2022 involved 21 studies showed that the pooled sensitivity of HPV test from urine samples was 76% (with a 95% confidence interval of 56–95), contrasting with a higher 97% (95% CI: 0.93–1.00) observed in samples collected by clinicians for the detection of CIN2 or worse. In the subsequent follow-up studies, pooled sensitivity for detection of CIN2 or worse was 79% (95% CI = 0.72–0.86) and 93% (95% CI = 0.89–0.96) in urine and clinician-collected samples, respectively. The specificity in urine (48%, 95% CI = 0.42–0.54) and clinician-collected samples (42%, 95% CI = 0.36–0.48) were comparable10. A study from Makioka et al. indicated that HPV E7 oncoproteins can be tested in 80% (4/5) of urine samples from women with HPV16-positive CIN1, 71% (5/7) of urine specimens from CIN2 patients, and 38% (3/8) of urine specimens from CIN3 patients11. These data suggest that using urine for HPV-related testing is feasible and represents a promising avenue for future diagnostic approaches.

The results showed that the sensitivity of urine and vaginal samples for detection of CIN2 + with CerviClear® assay was 86.70% and 90.64% respectively, indicating that the sensitivity of urine was lower than the cervical sample (86.70% vs 93.60%), while the sensitivity of vaginal and cervical sample was comparable (90.64% vs 93.60%). Faruk and colleagues observed a significantly lower sensitivity(77.6%, 95%CI: 66.8–88.4%) in urine samples using Colli-Pee12, however, Dorthe and colleagues demonstrated that urine and vaginal samples were comparable to the cervical samples, with the sensitivity of 93% and 96% in urine and vaginal for detection of CIN2 + respectively13. The possible explanations for the differences may be related to the limited sample size in other studies and disparities in sample collection and preservation among studies. Thus, standardized protocol for self-collected samples shows the crucial importance of large-scale application.

In the consistency analysis of urine, vaginal and cervical HPV detection, the agreement was 78.15% (95%CI: 76.03–80.16) between urine and cervical samples, and 85.71% (95%CI: 83.89–87.39) between vaginal and cervical samples. The urine sample showed lower agreement than the vaginal sample when compared to the cervical sample, which may be related to the lower concentration of HPV DNA in urine. But further data analysis found that the infection of HPV16/18 was sustainably consistent with cervical samples, so it seems that the relatively poor performance of other high-risk types contributed to the statistical difference in the agreement between self-collected and clinician-collected samples. Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated that the infection of HPV 16/18 played the most important role for CIN2 + and could be responsible for the pathogenesis of the lesions in the majority of incidences14. In the current study, the agreement indicated that self-collected-based HPV DNA assay can be used for identifying the 2 most carcinogenic HPV genotypes.

It is important to realize that the accuracy of self-collected samples for detecting CIN2 + may vary depending on several factors, such as the study population, sample collection method, and type of HPV assay used. Additionally, self-collected samples have been found to have lower sensitivity compared to clinician-collected cervical samples, but they are still considered useful for screening, especially for individuals who are unable or reluctant to undergo a clinician-collected cervical sample.

The study’s limitation was that we only included the referred population which may generate selection bias and variation compared to the population-based screening program. And it was a cross-sectional study so longitudinal studies will be necessary to confirm the value.

In conclusion, self-collected urine and vaginal samples have moderate accuracy for detecting CIN2 + and may be used as an alternative screening tool for cervical cancer. However, further studies are needed to fully evaluate the accuracy of self-collected samples and to determine the optimal sample collection method and HPV test to be used. Self-collected samples may provide an alternative screening method for cervical cancer and increase participation rates, especially in low- and middle-income countries where access to healthcare services is limited.

Data availability

The datasets collected during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263 (2024).

Ong, S. K. et al. Towards elimination of cervical cancer - human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Asian National Cancer Centers Alliance (ANCCA) member countries. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 39, 100860 (2023).

WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. Geneva:World Health Organization (2021).

Di, J., Rutherford, S. & Chu, C. Review of the cervical cancer burden and population-based cervical cancer screening in China. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 16(17), 7401–7407 (2015).

Control, C. C. C. A guide to essential practice (World Health Organization, 2014).

Hohn, A. K. et al. 2020 WHO classification of female genital tumors. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 81(10), 1145–1153 (2021).

Cho, H. W. et al. Performance and diagnostic accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected urine and vaginal samples in a referral population. Cancer Res. Treat. 53(3), 829–836 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Comparison of the performance of paired urine and cervical samples for cervical cancer screening in screening population. J. Med. Virol. 92(2), 234–240 (2020).

Bober, P., Firment, P. & Sabo, J. Diagnostic test accuracy of first-void urine human papillomaviruses for presence cervical HPV in women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18(24), 13314 (2021).

Cho, H. W. et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus tests on self-collected urine versus clinician-collected samples for the detection of cervical precancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 33(1), e4 (2022).

Makioka, D. et al. Quantification of HPV16 E7 oncoproteins in urine specimens from women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Microorganisms 12(6), 1205 (2024).

Ertik, F. C. et al. CoCoss-trial: Concurrent comparison of self-sampling devices for HPV-detection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(19), 10388 (2021).

Ornskov, D. et al. Clinical performance and acceptability of self-collected vaginal and urine samples compared with clinician-taken cervical samples for HPV testing among women referred for colposcopy. A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11(3), e41512 (2021).

Serrano, B. et al. Epidemiology and burden of HPV-related disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 47, 14–26 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Particularly grateful to all the people who have given help on the article.

Author order was determined according to increasing seniority and contribution.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design:XueJ Chen,Jing Shu,XiaoT Yu;Material preparation, data collection, and analysis:LongM Huang,XiaoJ Wang,Xia Zheng,Jiong Ma,Feng Gao,XiaoY Chen;Manuscript writing:ChunX Yan,ShanQ M,XiaoQ Li;All authors also read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Zhejiang, China(A2021001432). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, C., Ma, J., Zheng, X. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected samples among women referred for colposcopy. Sci Rep 15, 2513 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86943-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86943-7