Abstract

We aimed to investigate the demographic characteristics, common chief complaints, and diagnosis of geriatric cancer-related emergency department (ED) visits and trends of ED outcomes. This retrospective observational study included all ED visits in South Korea between 2016 and 2020. The study population was older people ≥ 65 years living with cancer who visited ED with cancer-related problems. The demographics, common diagnoses, and ED outcomes were investigated. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to investigate factors associated with mortality. Geriatric cancer-related ED (GCED) visits were 746,416 cases over 5 years. The proportion of older adults among cancer-related ED visits increased from 50.1% in 2016 to 55.3% in 2020. The proportion of the “oldest old” (≥ 85 years) increased from 9.6 to 12.1%. For GCED, the ward admission rate after ED treatment was 60.2% and in-hospital mortality rate was 11.8%. Both of these increased with age group (“young old” (65–74), “middle old” (75–84), and “oldest old” (≥ 85 years) groups admission rates: 56.1%, 62.8%, and 68.0%; and mortality rates: 10.0%, 12.7%, and 15.7%, respectively). The most common diagnosis was pneumonia (4.9%). Old age and ambulance use were also associated with mortality. Older adults account for more than half of cancer-related ED visits, and their number is increasing every year. GCED visits are associated with high hospitalization and mortality, especially among the oldest old. It is important to prepare for a rise in GCED visits is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

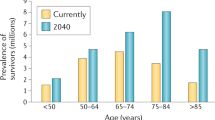

In this aging era, the number of people living with cancer (PLWC) is increasing worldwide1. Cancer is a major public health burden, and its importance as a leading cause of death has increased2. It was estimated that the number of new cancer cases worldwide in 2020 was 19.3 million, and that approximately 10 million people were estimated to have died from cancer3. The global cancer burden is estimated to increase to 28.4 million cases by 20403. Owing to the nature of cancer, which occurs more frequently with aging, a significant proportion of PLWC are older adults, and this proportion is expected to increase4.

The emergency department (ED) is an important medical resource requiring considerable manpower, facilities, and equipment5. EDs operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week; therefore, they not only treat emergent problems but also handle acute exacerbations of chronic diseases6,7. As the population ages, ED visits by patients with chronic diseases increase8,9,10. PLWC visit ED for various reasons7,11. Cancer can cause uncomfortable symptoms, and various complications and side effects arising during anti-cancer treatment can result in ED visits12,13. As the number of PLWC increases, their ED visits also increase7,14. Previous studies reported that cancer-related ED visits account for 3–5% of all ED visits7,14,15. Among PLWC, adults over 65 years (older PLWC) are more likely to experience various problems caused by cancer and its treatment, leading to an expected increase in ED visits16. Generally, older adults who visit the ED more frequently experience greater urgency, have longer ED stays, are more likely to be hospitalized or have repeated ED visits, and have higher rates of negative health outcomes after ED discharge9. While older PLWC are increasing and may have poorer ED outcomes, there is limited information about those older PLWC visiting the ED for cancer-related problems.

The increased ED visits and resulting overcrowding are critical problems for many healthcare systems8,17. For an ED to function properly, it is important to understand the characteristics of increased patient groups, such as older PLWC, and prepare an appropriate response according to the expected situation. To reduce ED visits for PLWC, it is necessary to identify the reasons behind their ED visits, considering that such experience can be stressful for both patients and their caregivers11. Understanding the trends and characteristics of cancer-related ED visits of older PLWC can be the first step toward improving the quality of cancer care and preparing for an appropriate ED operation. This study aimed to investigate the demographic characteristics, common chief complaints, and common diagnosis of geriatric cancer-related emergency department (GCED) visits and trends of ED outcomes using a nationwide ED database.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This retrospective observational study was conducted using data from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) database of South Korea. NEDIS is a nationwide ED database operated by the National Emergency Medical Center under the Ministry of Health and Welfare since 2013. Over 400 EDs were enrolled in NEDIS in 2022, and they usually transmit ED-related clinical and administrative information within 14 days of discharge from the ED or hospital18. The NEDIS database includes information on patient demographics (age and sex) and prehospital, ED, and disposition information. Designated trained coordinators manage data quality and the uploading processes in each institution18.

Study setting

South Korea has an area of 100,210 km2 and a population of 50 million. The proportion of the older adults aged 65 or older of the total population continues to increase from 13.6% in 2016 to 15.7% in 2020. South Korea has a national health insurance (NHI) system, which is a single insurer operated by the government that covers inpatient, outpatient, and emergency care. The EDs are classified into four levels according to resources and capacity. Level 1 is the ED with the most resources and capabilities. All citizens can visit the ED without restrictions under NHI coverage, ensuring high access to emergency care19.

Study population

The study population was all older adult patients who visited the EDs with cancer-related problems between January 2016 and December 2020. Among the total ED visits during the study period, patients aged 65 years or older with cancer-related visits were included as the study population excluding patients with unknown age and patients who visit ED for issuance of medical documentation.

In South Korea, the NHI provides universal health coverage and additional benefits for designated chronic diseases, such as cancer20. Since PLWC has lower out-of-pocket expenditures when they use medical services, including emergency care for cancer-related problems, the doctor who directly treats a patient in an ED determines whether problems are directly related to cancer or not and applied a cancer diagnosis if they are related. The diagnosis entered by the doctor is periodically reevaluated by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Services, and if entered incorrectly, insurance payment cannot be received, so doctors rigorously evaluate whether the visit is related to cancer and enter a correct diagnosis. The NEDIS database collects diagnosis codes at the time of discharge from the ED or hospital (up to 40) using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10). For patients discharged immediately from the ED, the diagnosis at the time of discharge from the ED is collected, and for patients hospitalized after ED treatment and then discharged, the diagnosis entered at the time of hospital discharge is used. Since a cancer diagnosis is entered only for ED visit for cancer-related problems, only those with diagnosis codes C00–C97 (malignant neoplasm) in the NEDIS database was defined as a cancer-related ED visit.

Among the 43,477,822 ED visits between 2016 and 2020, cancer-related ED visits totaled 1,421,501 (3.3%), Excluding patients with unknown age and cases for issuance of medical documentation, the total study population of cancer-related ED visits by older adults (GCED visits) was 746,416 (Supplement Fig. 1).

Outcome measures and variables

The exposure was the age group of older adults: “young old” (65–74), “middle old” (75–84), and “oldest old” (≥ 85 years) groups. The study outcomes were following: (1) in-hospital mortality including ED and hospital death, (2) total hospital admissions after ED treatment (ward and intensive care unit (ICU)), and (3) ICU admissions after ED treatment.

The following details were collected from the NEDIS database: (1) patient’s demographic information (age, sex, and type of insurance [NHI, Medicaid, and other or unknown]); (2) prehospital and ED visit information (date and time of ED visit, use of ambulance accessed through 119 or not, region of ED [metropolitan or not], and level of ED [1,2,3,4]); (3) ED treatment information (mental status at ED arrival [alert, verbal, pain response, and unresponsive], chief complaint of ED visit, ED disposition [discharge, transfer-out, ward admission, ICU admission, death, and others], and ED discharge diagnosis code); (4) hospital treatment in case of hospitalization after ED treatment (hospital discharge disposition [discharge, transfer-out, death, and others], and hospital discharge diagnosis code). About insurance, basically all citizens are registered in NHI, and low-income people are enrolled in Medicaid, so their out-of-pocket costs are lower. If it was covered by car insurance, etc., it was classified as others. In South Korea, 119 ambulance is a public emergency medical sertice system operated exclusively by the National Fire Agency (NFA) and anyone can use it for free in emergencies. If a patient called the NFA dispatch center (number 119) and visited the ED by taking a 119 ambulance, it was defined as use of 119 ambulance. In mental status at ED entrance, verbal and pain refer to whether patient is reponding to a vebal stimulus or to pain. Cases such as patients escaping from the ED or hospital were classified as others in disposition.

Statistical analysis

The trends in the proportion of geriatric cancer-related ED visits among total cancer-related ED visits and distribution of age groups among older adults were investigated by year: “young old” (65–74), “middle old” (75–84), and “oldest old” (≥ 85 years) groups. Temporal trends were evaluated by the Cochran-Armitage test for trends. The patient demographics and ED visit-related characteristics are presented according to age groups. Categorical variables are presented as counts and proportions and were compared and tested for statistical significance using the chi-square test. Non-parametric continuous variables are presented as medians and quartiles and were compared and tested for statistical significance using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The yearly trend of the study outcomes is presented by age group and tested by Cochran-Armitage test for trends. The top 15 most common chief complaints for visiting the ED and discharge diagnosis are presented by age groups. If a patient is discharged from the ED without being admitted to ward, the diagnosis upon discharge from the ED is used as discharge diagnosis, and if the patient is admitted to ward from the ED, the diagnosis at the time of discharge after hospitalization is used. When we investigated the diagnosis codes, if only a cancer diagnosis (ICD-10 code C) was included in the ED or hospital discharge diagnosis code, it was classified into the “only cancer diagnosis” category. The ED outcomes for each of the top 15 common diagnoses are presented by age groups. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to investigate the factors associated with mortality in the study population by applying factors known to affect ED outcome in previous studies as covariate7. Finally, age, sex, type of insurance, night-time visit, weekend visit, use of 119 ambulance, and level of ED were used as covariates7.

Data management and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Trends of geriatric cancer-related ED visits

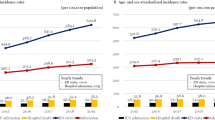

The total number of GCED was 746,416. The proportion of older adults with cancer-related ED visits increased from 50.1% in 2016 to 55.3% in 2020 (p value < 0.01). Among older adults, the proportion of the “oldest old” also increased from 9.6% in 2016 to 12.1% in 2020 (p value < 0.01) (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the study population

The median (IQR) age was 75 (70–80) years. 37.0% were female, and 8.5% were on Medicaid. Among the geriatric population, 47.8% were “young old”, 41.4% were “middle old”, and 10.8% were “oldest old”.

The total admission rate to a hospital in-ward after ED treatment was 60.2%, and the older the patient, the higher the admission rate (“young old”, 56.1%; “middle old”, 62.8%; and “oldest old”, 68.0%, p value < 0.01). The overall ICU admission rate was 6.6%, and the older the patient, the higher the ICU admission rate (“young old”, 5.4%; “middle old”, 7.3%; and “oldest old”, 9.2%, p value < 0.01). The in-hospital mortality rate was 11.8% overall, and the older the patient, the higher the mortality rate (“young old”, 10.0%; “middle old”, 12.7%; and “oldest old”, 15.7%, p value < 0.01) (Table 1).

The total admission, ICU admission, and mortality rate decreased from 2016 to 2019. However, they then slightly increased in 2020, with all outcomes being higher in the older age groups (Supplement Fig. 2).

Top 15 chief complaints and diagnoses for ED visits

The most common chief complaints were abdominal pain (11.9%), dyspnea (11.2%), and fever (9.7%). Among the “oldest old” patients, general weakness was more common than fever (general weakness, 8.3%; fever, 7.3%) (Table 2). The most common diagnoses were pneumonia (4.9%), followed by other digestive diseases (2.9%) and gastroenteritis (2.7%).

Mortality and hospitalization rate for top 15 diagnoses

Among the top 15 diagnoses, those with the highest mortality rates were pneumonia (25.7%), dyspnea (22.5%), and acute renal failure (20.2%). Pneumonia was associated with higher hospitalization rates (“young old”, 84.4%; “middle old”, 86.9%; and “oldest old”, 87.5%) and mortality rate (“young old”, 23.6%; “middle old”, 26.6%; and “oldest old”, 29.0%) with age (Table 3).

Factors associated with in-hospital mortality owing to geriatric cancer-related ED visits

Of the patients, 11.8% died in the hospital. The odds of mortality were significantly higher in the “middle old” (AOR 1.24 (95% CI: 1.23–1.26)) and “oldest old” (AOR 1.52 (95% CI: 1.48–1.55)) groups than in the “young old” group. Ambulance use (AOR 2.31 (95% CI: 2.27–2.34)) was also associated with higher odds. Factors associated with lower risk of mortality included female sex (AOR 0.88 (95% CI: 0.86–0.89)), medical aid (AOR 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85–0.90)), night-time visit (AOR 0.91 (95% CI: 0.90–0.93)), and weekend visit (AOR 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91–0.94)) (Supplement Table 1).

Discussion

As the number of older PLWC has increased, this study investigated the characteristics and trends of GCED visits in South Korea using a nationwide ED database. During the five years from 2016 to 2020, the number of GCED visits was approximately 0.75 million, averaging 0.15 million visits per year. It accounted for more than half of all cancer-related ED visits. Overall, 60% of these patients were hospitalized, and more than 10% died in the hospital. The most common diagnosis was pneumonia. Understanding the reasons for cancer-related ED visits of older PLWC is essential for preparing for the increase in ED visits by older PLWC.

PLWC inevitably visit the ED for symptom control and management of complications caused by the treatment21,22. Previous studies reported that 3–5% of all ED visits are related to cancer, and PLWC are a high-burden population with higher hospitalization rates (over 50%) and ICU admission rates (over 5% after ED treatment)7,14. The risk of developing problems during anti-cancer treatment is high in older PLWC23. Although more than 50% of cancer-related ED visits were made by adults aged ≥ 65 years7,14, there is limited information about older PLWC visiting ED with cancer-related problem. The strength of this study is that it investigates who visit the ED and for what reasons among older PLWC, who account for a significant proportion of cancer-related ED visits using a nationwide ED database. The number of GCED visits is increasing annually, and the proportion of the oldest old group among older PLWC is also increasing. Even among older PLWC, the oldest old age group has higher admission and mortality rates. The common reasons for ED visits among older PLWC were abdominal pain, dyspnea, and fever. However, in those aged 85 years or older, general weakness was more common than fever. Just as it is known that older adults often complain of non-typical symptoms associated with various diseases, such as myocardial infarction, older PLWC may also complain of non-typical symptoms. This is why caution is necessary when treating the oldest old PLWC in the ED24.

Except for cancer, the most common diagnosis in the ED was pneumonia. The admission rate for GCED visits with pneumonia was over 80%, and one-fourth of the patients died in the hospital. In particular, the fact that one-third of the “oldest old” patients with pneumonia died indicates that the burden of emergency care may increase as the number of older PLWC increases. Previous studies have reported high hospitalization and mortality rates when patients with cancer-related ED visits were diagnosed with serious diseases, such as pneumonia and agranulocytosis7. This study found that the burden is even greater for oldest age group. The in-hospital mortality rate of GCED visits exceeded 10%, rising to over 15% for those aged over 85 years. This is more than 10 times higher than the mortality rate of 1.3% for all patients visiting the ED and 1.0% for patients without cancer7. When older PLWC visit the ED with cancer-related problem, 15 out of 100 die; they should be carefully observed and treated in the ED.

Another consideration is that the older PLWC examined in this study included patients at various cancer stages and treatment statuses. Since only cases that visited the ED for cancer-related problems were included, patients whose cancer was completely cured and who were cancer-free were excluded, but all older PLWC in different treatment status were included: curative treatment, palliative treatment, and no cancer treatment in the palliative stage at the end-of-life. Previous study reported that 55% of patients who died in the ED did not receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation before death, and 23% of such patients were PLWC25. It should be considered that some older PLWC may visit the ED at a stage when end-of-life care is needed instead of active treatment at an ED or first aid. The ED allows for the treatment of both the acute deterioration of chronic diseases and emergency conditions; however, for patients whose death is shortly predicted with incurable disease, there may be a more appropriate place to die, such as hospice. Even though this study was unable to identify such patient groups, it is important to prepare for end-of-life care in the ED while also providing appropriate palliative care for PLWC in settings other than the ED, given the rise in ED visits by older PLWCs. Additionally, more supportive care options other than ED are needed for PLWC whose stages do not require end-of-life care. Since it is well known that PLWC experience various cancer-related symptoms and anti-cancer treatment-related complications, in addition to active in-advance symptom control in the outpatient clinic, it is desirable to plan a telehealth program or home-based medical care program that allows patients to receive medical services continuously before visiting the ED26. Since a visit to the ED can itself be a traumatic experience for PLWC and their care partners, securing a variety of medical resources available outside of the ED can help not only reduce ED crowding but also improve the quality of care for PLWC.

This study had some limitations. Based on the diagnosis code entered into the NEDIS database, if a cancer diagnosis appeared in the ED discharge or hospital discharge code, it was classified as a cancer-related ED visit. If the diagnosis was entered incorrectly, the cancer-related ED visit may have been misclassified. However, in South Korea, where the NHI system is implemented, PLWC receive additional insurance coverage benefits for cancer-related treatments. Therefore, it is unlikely that a cancer diagnosis was omitted for PLWC or incorrectly recorded in their medical records. Second, NEDIS is an ED-based database that does not contain detailed information on cancer, such as stage, diagnosis timing, and treatment status. Therefore, it was unknown whether older PLWC who visited the ED were actively undergoing chemotherapy or required end-of-life care. Third, PLWC can visit the ED if multiple problems occur simultaneously. When multiple diagnoses other than cancer were present, the analysis was based on the first listed diagnosis in the NEDIS database, as the most important reason for visiting the ED was recorded first. Fourth, the COVID-19 pandemic happened in 2020 during the study period. During this period, in South Korea, patients suspected of COVID-19 were treated at a separate screening clinic rather than the ED to prevent the spread of infection through the ED. These strategies may have influenced the study results.

In conclusion, more than 50% of PLWC who visited the ED were aged 65 years or older, with this proportion increasing annually, particularly among the “oldest old”. More than 60% of them are hospitalized and more than 10% die in the hospital. As the global population ages and the number of PLWC increases as medical technology advances, the number of older PLWC with high burden is expected to continue to increase. More planning is needed to improve the quality of cancer care for older PLWC in the ED and reduce the burden of the ED.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available because it was used under license from the National Emergency Medical Center in South Korea for the current study but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 7–33 (2022).

Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Weiderpass, E. & Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 127, 3029–3030 (2021).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Pilleron, S. et al. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: A population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 144, 49–58 (2019).

Bamezai, A., Melnick, G. & Nawathe, A. The cost of an emergency department visit and its relationship to emergency department volume. Ann. Emerg. Med. 45, 483–490 (2005).

Hasegawa, K., Tsugawa, Y., Tsai, C. L., Brown, D. F. & Camargo, C. A. Frequent utilization of the emergency department for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 15, 40 (2014).

Lee, S. Y., Ro, Y. S., Shin, S. D. & Moon, S. Epidemiologic trends in cancer-related emergency department utilization in Korea from 2015 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 11, 21981 (2021).

Tang, N., Stein, J., Hsia, R. Y., Maselli, J. H. & Gonzales, R. Trends and characteristics of US Emergency Department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA 304, 664–670 (2010).

Aminzadeh, F. & Dalziel, W. B. Older adults in the emergency department: A systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann. Emerg. Med. 39, 238–247 (2002).

Roberts, D. C., McKay, M. P. & Shaffer, A. Increasing rates of emergency department visits for elderly patients in the United States, 1993 to 2003. Ann. Emerg. Med. 51, 769–774 (2008).

Panattoni, L. et al. Characterizing potentially preventable cancer-and chronic disease-related emergency department use in the year after treatment initiation: A regional study. J. Oncol. Pract. 14, e176–e185 (2018).

Jairam, V. et al. Treatment-related complications of systemic therapy and radiotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1028–1035 (2019).

Gallaway, M. S. et al. Emergency department visits among people with cancer: Frequency, symptoms, and characteristics. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2, e12438 (2021).

Rivera, D. R. et al. Trends in adult cancer-related emergency department utilization: An analysis of data from the nationwide emergency department sample. JAMA Oncol. 3, e172450 (2017).

Hsu, J. et al. National characteristics of Emergency Department visits by patients with cancer in the United States. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 2038–2043 (2018).

Balducci, L. & Extermann, M. Management of cancer in the older person: A practical approach. Oncologist 5, 224–237 (2000).

Yarmohammadian, M. H., Rezaei, F., Haghshenas, A. & Tavakoli, N. Overcrowding in emergency departments: A review of strategies to decrease future challenges. J. Res. Med. Sci. 22, 23 (2017).

Yoo, H. H. et al. Epidemiologic trends of patients who visited nationwide emergency departments: A report from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) of Korea, 2018–2022. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 10(S), S1–S12 (2023).

Lee, S. Y., Khang, Y. H. & Lim, H. K. Impact of the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak on emergency care utilization and mortality in South Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 60, 796–803 (2019).

Kim, S. & Kwon, S. Impact of the policy of expanding benefit coverage for cancer patients on catastrophic health expenditure across different income groups in South Korea. Soc. Sci. Med. 138, 241–247 (2015).

Kirkland, S. W., Garrido-Clua, M., Junqueira, D. R., Campbell, S. & Rowe, B. H. Preventing emergency department visits among patients with cancer: A scoping review. Support. Care Cancer 28, 4077–4094 (2020).

Coyne, C. J. et al. Cancer pain management in the emergency department: A multicenter prospective observational trial of the Comprehensive Oncologic Emergencies Research Network (CONCERN). Support. Care Cancer 29, 4543–4553 (2021).

Gordon, J., Sheppard, L. A. & Anaf, S. The patient experience in the emergency department: A systematic synthesis of qualitative research. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 18, 80–88 (2010).

Carreca, I., Balducci, L. & Extermann, M. Cancer in the older person. Cancer Treat. Rev. 31, 380–402 (2005).

Carro, A. & Kaski, J. C. Myocardial infarction in the elderly. Aging Dis. 2, 116–137 (2011).

Lee, S. Y., Ro, Y. S., Shin, S. D., Ko, E. & Kim, S. J. Epidemiology of patients who died in the emergency departments and need of end-of-life care in Korea from 2016 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 13, 686 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Medical Center for Data Use (N20223420911). The NEDIS data were administered by the National Medical Center, and financial support was provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center (PACEN) funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant Number: RS-2021-KH120239).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Lee SY, Ko JI. Data curation: Lee SY, Ko JI. Formal analysis: Lee SY. Methodology: Lee SY. Visualization: Lee SY. Project administration: Cho BL, Yoo SH, Kim KH, Lee SY. Writing—original draft: Lee SY, Ko JI. Writing–review and editing: Lee SY, Ko JI, Cho BL, Yoo SH, Kim KH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (approval no. E-2209-047-1357). All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent to participate

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (approval no. E-2209-047-1357).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, JI., Lee, S.Y., Yoo, S.H. et al. Epidemiologic trends and characteristics of cancer-related emergency department visits of older patients living with cancer in South Korea. Sci Rep 15, 4767 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89104-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89104-y