Abstract

Sjögren’s syndrome, a chronic autoimmune disorder, markedly impairs health-related quality of life, sometimes to levels perceived as worse than death. This significant decline prompts concerns about mental health outcomes, including the risk of suicide. The present study investigates whether individuals with Sjögren’s syndrome is associated with an increased risk of attempted suicide than those without the condition. Utilizing data from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010, we conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 20,685 patients diagnosed with Sjögren’s syndrome and a comparison cohort of 103,425 propensity-score matched individuals without the syndrome. We examined the one-year suicide attempt-free survival using the log-rank test and employed Cox proportional hazards regression to assess the risk of attempted suicide post-diagnosis after taking soico-demographic and clinical variables into considerations. Within the 124,110 sampled patients, the incidence rates of attempted suicide were statistically and significantly higher in the Sjögren’s syndrome cohort during the one-year follow-up: 0.247 per 100 person-years (95% CI = 0.186–0.322) compared to 0.014 per 100 person-years (95% CI = 0.008–0.022) in the comparison cohort. The adjusted hazard ratio for attempted suicide was markedly elevated at 18.054 (95% CI = 9.992–32.623) in the study cohort than the comparison group. The findings reveal a profoundly increased risk of attempted suicide on patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. This underscores the need for enhanced psychiatric evaluation and intervention strategies within this vulnerable population to address the elevated suicide risk effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide ranks as the 14th highest cause of death worldwide1. Every year, close to 48,000 individuals in the United States and over 700,000 people globally lose their lives to suicide2,3. Moreover, attempts to commit suicide vastly outnumber the actual suicide fatalities, with the U.S. recording over 30 suicide attempts for every suicide death annually4. Healthcare providers bear the weighty responsibility of doing all they can to curb suicidal tendencies in their patients, but suicide prevention presents a significant obstacle in clinical settings. The most optimal approach to tackling this issue is primary prevention, aimed at reducing the emergence of new instances. On the other hand, secondary prevention focuses on minimizing the chances of high-risk patients engaging in suicide attempts5. Therefore, pinpointing the specific groups that are more prone to attempting suicide and providing them with appropriate treatment is a pivotal aspect in the endeavors to prevent suicide, especially in primary care settings6.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a persistent and complex autoimmune condition that predominantly affects the lacrimal and salivary glands, leading to symptoms such as dry eyes and mouth, and in some cases, glandular enlargement. Globally, it is estimated to affect between 1.6 and 8.4 individuals per 10,0007. While it is primarily known for its glandular symptoms, SS can also manifest in a variety of extraglandular ways, including but not limited to fatigue, musculoskeletal issues, skin rashes, sexual dysfunctions8, and complications involving vital organs such as the lungs, kidneys, liver, and nervous system. Moreover, individuals with SS often experience a significant decline in their health-related quality of life (HRQoL), a deterioration attributed to a range of symptoms including but not limited to dry mouth and eyes, altered chemosensory functions9, interstitial lung disease10, peripheral neuropathy11, and a substantial burden of pain and fatigue12. Despite not generally affecting life expectancy, the syndrome can impose a considerable burden on individuals, often leading to substantial work disability and associated costs13. It is not uncommon for individuals with SS to experience a decline in HRQoL to levels likened to, or even worse than, death14.

Despite its significant impact on individuals’ lives, SS is sometimes erroneously perceived as a benign ‘nuisance’ disease, especially in cases without systemic manifestations. This study seeks to further explore the implications of SS on individuals’ wellbeing, focusing on the Taiwanese population. Leveraging a comprehensive nationwide dataset, we aim to investigate a previously unexplored potential association between SS and the risk of attempted suicide, thereby shedding new light on the full spectrum of challenges faced by individuals with SS.

Methods

Database

For our retrospective cohort study, data were retrieved from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010 (LHID2010), a critical component of the National Health Insurance (NHI) program established in 1995. The NHI ensures comprehensive healthcare coverage for all Taiwanese citizens. The LHID2010 database contains detailed records from a random sample of 2,000,000 NHI enrollees. This rich dataset has been instrumental in facilitating a wide range of epidemiological studies by various Taiwanese educational and medical research institutions.

Our study also incorporated data from the Cause of Death Data File, maintained by Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. This dataset stands out for its integrity and completeness, achieved through the mandatory registration of critical life events such as births and deaths. It provides detailed information on the date and nature of death. Each death is cataloged with primary causes listed via ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes. Integrating the LHID2010 with the Cause of Death Data File enables us to meticulously track and analyze suicide incidents and other mortality data throughout the duration of our study, enhancing the depth and accuracy of our findings.

This study received ethical approval from the institutional review board of Taipei Medical University (TMU-JIRB N202308032). The informed consent was waived because all personal identifiers were removed from the data, ensuring complete anonymity of the information extracted from the LHID2010 and the Cause of Death Data File. This measure safeguards participant privacy while allowing comprehensive analysis of the health data for our study.

Study sample

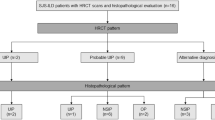

In this longitudinal observational research, we organized participants into a study cohort and a comparison cohort. When forming the study cohort, we accessed and reviewed the medical claims histories of all patients who were 20 years old or older and had been diagnosed with SS, as indicated by the ICD-9-CM 710.2 or ICD-10-CM M35.0 codes, from the database of outpatient hospital departments and clinics from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2018. It is important to note that in Taiwan, the diagnosis of SS is undertaken predominantly by specialized rheumatologists who perform detailed physical assessments and gather a range of laboratory data such as anti-SSA, anti-SSB readings, and unstimulated whole salivary flow rate tests. Furthermore, SS is recognized as one of 31 catastrophic illnesses in Taiwan, allowing officially registered patients to be absolved from medical copayments. To secure this financial relief, individuals must fulfill the criteria delineated in either the 2002 AECG, 2012 ACR, or 2016 ACR/EULAR classification standards, followed by a committee evaluation. This rigorous approach underpins our confidence in the high accuracy of SS diagnoses in Taiwan. Following this methodology, we pinpointed 21,269 individuals with SS to comprise our study cohort. As we delved deeper, we opted to omit patients who had recorded suicide attempts within three years before the established index date, narrowing down further by excluding those exhibiting additional suicide risk factors such as diagnosed substance use disorder (characterized by the ICD-9-CM 291, 292, 303 ~ 305 or ICD-10-CM code F10 ~ F19) and mental health conditions including anxiety and mood disorders (signified by the ICD-9-CM 295, 296, 300 or ICD-10-CM F20 ~ F42 codes). This process of elimination affected 584 individuals from the initial group. This stringent selection process culminated in a carefully curated study cohort, constituted of 20,685 SS patients (Fig. 1).

In establishing a comparison cohort for our research, we turned to the LHID2010 Registry, drawing from the pool of beneficiaries who were aged 20 years and above. Our initial step involved eliminating individuals who had a documented history of SS before the inception of the designated study timeframe. Subsequently, we devised a propensity score for every chosen participant with SS alongside the remaining candidates from the LHID2010 Registry. In determining these scores, we considered a variety of predictive factors such as age, gender, monthly earnings delineated into three categories based on the New Taiwan Dollar (NT) with the 2021 conversion rate being noted at US$1 to approximately NT$28, and the geographic locale categorized into Northern, Central, Southern, and Eastern regions. Moreover, the urbanization spectrum of the participant’s residence, ranked from one (most urbanized) to five (least urbanized), was taken into account, along with prevalent medical comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease. Once these propensity scores were computed, we proceeded to organize the remaining beneficiaries into quintiles predicated on their scores. To facilitate a meticulous patient matching, we applied the nearest neighbor technique within calipers using a predefined caliper value of 0.2, a strategy adopted to counter the potential hindrance in finding exact score-matched comparison subjects for every patient with SS. Further, we stipulated the index date for individuals in the comparison cohort as the day they first availed medical care in the index year corresponding to their matched SS cases. Before finalizing our comparison group, we undertook a stringent verification process to confirm that no individual had a recorded suicide attempt in the three-year period preceding their index date. Following the culmination of this rigorous selection procedure, our conclusive research sample emerged with a cohort comprising 20,685 patients with SS and a substantially larger comparison group encompassing 103,425 individuals. This meticulous methodological approach ensures a robust and comparative analysis grounded on comprehensive and diverse data sets.

Outcome variable

In this research, we maintained stringent oversight over the participating patients for a duration of one year starting from their index date, aiming to pinpoint any medical claims signifying attempts at suicide. The diagnostic codes employed to mark these instances were rooted in the ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM systems. Specifically, we scanned for the range E950 to E959 in the ICD-9-CM and identified distinct subsets within the ICD-10-CM, which included T14.91, codes spanning X60 to X84, and Y87.0, among others, with a focal point on the sixth character equating to “2”. However, we noted exceptions, seeking the fifth character to be “2” in particular codes such as T36.9, T39.9, T41.4, etc. Moreover, our diagnostic criteria encapsulated codes T51 to T65 guided by the sixth character “2”, but here too we carved out exemptions relying on the fifth character being “2” in codes like T51.9, T53.9, T54.9, and so forth. Our principal outcome variable was anchored on the occurrence of a diagnosed suicide attempt over the one-year observational window, expanding our definition to include any self-harming conduct carried out with a fatal intent, irrespective of the ultimate outcome of the action. Consequently, all fatalities attributed to suicide were encompassed under suicide attempts, offering a comprehensive view of both failed and successful attempts. To ascertain incidents of suicide resulting in death, we leveraged data from the authoritative Cause of Death Data File, ensuring the exhaustive incorporation of all suicide-related outcomes within our study parameters. This meticulous approach allowed for a detailed exploration of the manifestation of self-directed violent behavior with an intention to die, thereby offering deep insights into the severity and frequency of such incidents over the study period.

Statistical analysis

In our research, we utilized SAS statistical software (version 9.4) to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the one-year suicide-free survival rates between two cohorts, employing the log-rank test to investigate differences and Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate the one-year hazard of attempted suicide after the diagnosis of SS. We confirmed the validity of the proportional hazards assumption by demonstrating that the survival curves for both the study and comparison cohorts continued to show a proportional separation over time. The analysis was further refined by adjusting hazard ratios (HR) and calculating 95% confidence intervals (CI), with statistical significance established at p ≤ 0.05, allowing us to determine and quantify the differences in suicide risk between the cohorts effectively.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patients with SS and comparison cohort, revealing no statistically significant differences in sex (p > 0.999), age (p = 0.527), monthly income (p = 0.847), urbanization level (p = 0.972), or medical co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary heart disease (all p > 0.999). Nevertheless, there was a statistically significant difference in the geographic region distribution between patients with SS and comparison cohort (p < 0.001). Despite this, the large sample size likely contributed to the detection of significant p-values. To assess the practical significance of this difference, Cohen’s h was calculated, and the effect size for the geographic region variable was found to be less than 0.1. This indicates that, while statistically significant, the difference in geographic region between the cohorts was negligible, affirming the comparability of patients with SS and comparison cohort.

The incidence rates of attempted suicide within one year following the index date for 124,110 sampled patients was shown in Table 2. The overall incidence rate of attempted suicide during the one-year follow-up was 0.052 per 100 person-years (95% CI = 0.041–0.066), with rates of 0.247 (95% CI = 0.186–0.322) and 0.014 (95% CI = 0.008–0.022) per 100 person-years observed in patients with SS and comparison cohort, respectively. A log-rank test suggested that the patients with SS exhibited significantly lower suicide attempt-free survival when compared to the comparison cohort over the one-year follow-up period (p < 0.001). This difference is further illustrated in Fig. 2, which depicts the Kaplan-Meier suicide attempt-free survival curves for patients with SS and comparison cohort, highlighting the marked disparity in survival rates between patients with SS and comparison cohort.

The HRs for attempted suicide within one year of follow-up was also presented in Table 2. Cox proportional hazards analysis revealed that patients with SS had a significantly higher risk of attempted suicide than the comparison cohort, with a crude HR of 18.235 (95% CI = 10.095–32.941, p < 0.001). After adjusting for age, sex, monthly income, geographic region, urbanization level, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hypertension, the adjusted HR for suicide attempt in patients with SS remained elevated at 18.054 (95% CI = 9.992–32.623, p < 0.001). These findings underscore the significantly higher suicide risk among patients with SS, even after accounting for key demographic and clinical variables.

Table 3 presents the differences in clinical features between SS patients who attempted suicide and who did not. We found that patients who attempted suicide were more likely to be younger than those who did not (mean age 48.6 vs. 53.5 years, p = 0.037).

Discussion

In our understanding, this pioneering research, utilizing an extensive nationally representative dataset, is the foremost to identify that patients with SS face a pronounced risk of attempting suicide over a one-year observational period. After meticulously adjusting for demographics and coexisting conditions, the adjusted hazard ratio stands at a significant 18.054.

The exact cause for the heightened risk of suicide attempts in patients with SS remains elusive, and our research methods couldn’t delve into the core reasons for this link. Notably, various medical conditions, including asthma, cancer, and neurological diseases, among others, have been associated with reduced HRQoL and increased suicidality15,16,17,18,19. Patients with SS often exhibit a diverse range of symptoms, from the predominant sicca (dryness) due to exocrine gland dysfunction to extraglandular manifestations affecting various body systems. A significant portion also faces severe organ complications, such as central nerve system, or lung involvement. Many report fatigue and pain, irrespective of the organ affected, leading to a notably diminished HRQoL, sometimes equated to conditions worse than death14. This compromised quality of life, stemming from Sjögren’s syndrome and other mentioned illnesses, could potentially amplify suicidal tendencies.

Several other potential factors might associate SS with elevated suicide risk. The diagnosis can be a significant emotional stressor20, and the disease can lead to psychological challenges, including feelings of burdensomeness, cognitive impairment21,22, altered self-perception23, social limitations23, financial concerns24, and increased dependence on others25. Physical discomforts, notably poor sleep and pain21,26, add to the distress. Mental health issues, such as depression21,27, increased anxiety and psychosis28, further complicate the picture. Furthermore, autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and psoriasis had been report to have high risk for suicidality29,30. The autoimmune response in SS, particularly the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, may influence the central nerve system, such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, hippocampus, and serotonin levels, affecting behaviors and inducing fatigue. Given these potential links, physicians should remain vigilant about depression and suicide risks in SS patients.

Our research is deeply rooted in the data-rich environment of Taiwan’s NHI system, established in 1995. The near-universal coverage and affordability of the NHI ensure a broad representation, reducing selection biases and making it less influenced by socio-economic disparities, especially in marginalized areas. This inclusivity allows patients to seek treatment for a spectrum of ailments, from milder conditions like SS to critical ones like suicide attempts, without financial impediments. By leveraging claims data, we bypass the recall bias often associated with self-reported datasets. Furthermore, our methodological approach—a case-control design fortified by propensity score matching—enhances the robustness of our findings by minimizing potential biases and aligning cases and controls on various observed confounders, ensuring our conclusions’ validity and reliability.

Our research, while comprehensive, is not without limitations. The LHID2010 dataset, despite its breadth, doesn’t fully encompass crucial clinical nuances associated with Sjogren syndrome or dive deep into varied suicide risk factors—encompassing everything from personal traits to genetic predispositions and socio-environmental stressors. Our investigative lens, tuned to ICD-coded suicide attempts, omits aspects like suicidal thoughts or finalized acts. Moreover, given the complex and multifaceted nature of suicide, often interlinked with diverse psychiatric ailments, our exclusion of diagnosed cases might inadvertently bypass those undiagnosed due to Taiwan’s prevailing mental health stigma. Fortunately, any resultant misclassifications should be fairly spread across both our study and reference cohorts. Additionally, there’s a plausible underrepresentation of non-emergency suicide attempts. While the structured nature of ICD codes, vetted by certified professionals, is commendable, it’s not a full replacement for detailed clinical validation. A more holistic dataset integration—melding National Health Insurance data with subsequent suicide reporting systems—would’ve enriched our insights, but timelines and legislative changes, like Taiwan’s 2019 Suicide Prevention Act, inhibited such access. Lastly, given our study’s demographic focus, extrapolating our conclusions to diverse ethnic or cultural groups requires cautious interpretation.

Conclusion

Our research underscores an alarming association between patients with SS and elevated suicide attempt rates, positioning suicide as a potentially dire repercussion of SS affliction. These revelations bear significant weight for healthcare practitioners tending to patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, arming them with empirical evidence to counsel patients on the heightened suicide attempt risks. Thus, individuals diagnosed with SS warrant meticulous assessment, and proactive steps, encompassing early intervention, swift identification, and timely therapeutic interventions, are imperative to curtail the frequency of suicide attempts.

Data availability

The LHID2010 that support the findings of this study can be reached by researchers through a formal application process addressed to the HWDC, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp-5119-59201-113.html).

References

Bryleva, E. Y. & Brundin, L. Suicidality and activation of the kynurenine pathway of Tryptophan metabolism. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 31, 269–284 (2017).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide Data and Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html [Accessed: 11 September 2023].

World Health Organization. Suicide. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide [Accessed: 11 September 2023].

Han, B. et al. Estimating the rates of deaths by suicide among adults who attempt suicide in the United States. J. Psychiatr. Res. 77, 125–133 (2016).

Sher, L. Preventing suicide. Qjm 97 (10), 677–680. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hch106 (2004).

Mughal, F., Gorton, H. C., Michail, M., Robinson, J. & Saini, P. Suicide prevention in primary care. Crisis 42 (4), 241–246 (2021).

Barrio-Cortes, J. et al. Prevalence and comorbidities of Sjogren’s syndrome patients in the community of Madrid: A population-based cross-sectional study. Joint Bone Spine 90 (4), 105544 (2023).

Gözüküçük, M. et al. Effects of primary Sjögren’s syndrome on female genitalia and sexual functions. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 39 Suppl 133 (6), 66–72 (2021).

Šijan Gobeljić, M., Milić, V., Pejnović, N. & Damjanov, N. Chemosensory dysfunction, oral disorders and oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 3 (1), 187 (2020).

Zhao, R. et al. Associated factors with interstitial lung disease and health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Rheumatol. 39 (2), 483–489 (2020).

Jaskólska, M. et al. Peripheral neuropathy and health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a preliminary report. Rheumatol. Int. 40 (8), 1267–1274 (2020).

Dias, L. H., Miyamoto, S. T., Giovelli, R. A., de Magalhães, C. I. M. & Valim, V. Pain and fatigue are predictors of quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Adv. Rheumatol. 29 (1), 28 (2021).

Miyamoto, S. T., Valim, V. & Fisher, B. A. Health-related quality of life and costs in Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 18 (6), 2588–2601 (2021).

Tarn, J. et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: longitudinal real-world, observational data on health-related quality of life. J. Intern. Med. 291 (6), 849–855 (2022).

de Albornoz, S. C. & Chen, G. Relationship between health-related quality of life and subjective wellbeing in asthma. J. Psychosom. Res. 142, 110356 (2021).

Jung, J. Y. & Yun, Y. H. Importance of worthwhile life and social health as predictors of suicide ideation among cancer patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 40 (3), 303–314 (2022).

Tsalta-Mladenov, M. & Andonova, S. Health-related quality of life after ischemic stroke: impact of sociodemographic and clinical factors. Neurol. Res. 43 (7), 553–561 (2021).

Iessa, N., Murray, M. L., Curran, S. & Wong, I. C. Asthma and suicide-related adverse events: a review of observational studies. Eur. Respir. Rev. 20 (122), 287–292 (2011).

Erlangsen, A. et al. Association between neurological disorders and death by suicide in Denmark. Jama 4 (5), 444–454 (2020).

Howarth, E. J. et al. Are stressful life events prospectively associated with increased suicidal ideation and behaviour? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 1 266 731–742 (2020).

Goulabchand, R. et al. The interplay between cognition, depression, anxiety, and sleep in primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Sci. Rep. 1 (1), 13176 (2022).

Tezcan, M. E. et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome is associated with significant cognitive dysfunction. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 19 (10), 981–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.12912 (2016).

Rojas-Alcayaga, G. et al. Illness experience and quality of life in Sjögren syndrome patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2 19 (17), (2022).

Westerlund, A., Kejs, A. M. T., Beydogan, H. & Gairy, K. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A retrospective cohort study of burden of illness in Sweden. Rheumatol. Ther. 8 (2), 955–971 (2021).

Cukrowicz, K. C., Cheavens, J. S., Van Orden, K. A., Ragain, R. M. & Cook, R. L. Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychol. Aging 26 (2), 331–338 (2011).

Elman, I., Borsook, D. & Volkow, N. D. Pain and suicidality: insights from reward and addiction neuroscience. Prog. Neurobiol. 109, 1–27 (2013).

Margaretten, M. Neurologic manifestations of primary Sjögren syndrome. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 43 (4), 519–529 (2017).

Hammett, E. K. et al. Adolescent Sjogren’s syndrome presenting as psychosis: a case series. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 11 (1), 15 (2020).

Sadovnick, A. D., Eisen, K., Ebers, G. C. & Paty, D. W. Cause of death in patients attending multiple sclerosis clinics. Neurology 41 (8), 1193–1196 (1991).

Pompili, M. et al. Suicide risk and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with psoriasis. J. Int. Med. Res. 44 (1 suppl), 61–66 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“T.Z. and H.C. Lee participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. C.S. performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. Y.F. and H.C. Lin conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, prepared Fig. 1 and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.”

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, TH., Lee, HC., Cheng, YF. et al. Sjögren’s syndrome increased risk of attempted suicide. Sci Rep 15, 9379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92691-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92691-5