Abstract

Laparoscopic repair as an alternative option for pediatric inguinal hernia has increased worldwide. We aimed to analyze the surgical methods of inguinal hernia repair among children, adolescents and young adults, and evaluate the surgical outcomes of reoperation and postoperative complications. This is a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. 3249 inpatients who were ≤ 25 years and underwent inguinal hernia repair between 2015 and 2021 were included. Baseline data, hernia characteristics, surgical approach and technique, outcomes including reoperation and postoperative complications before discharge were identified from electronic medical records. Multivariable Cox regression and logistic regression were used to analyze the association between surgical methods and outcomes. Of all participants, 72.82% were children younger than 9 years, 79.62% were male, 81.19% underwent laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic sac high ligation was the mostly used method among infants and children who were younger than 13 years (from 61.11% in 10–12 years old to 96.77% in 0–3 years old), open and laparoscopic tension-free repairs were more common for adolescents and young adults older than 13 years (from 92.38% in 13–15 years old to 100% in 19–21 years old). During a median follow-up of 51.91 months, 24 (0.74%) reoperations were identified, including 3 (0.09%) ipsilateral recurrence, and 21 (0.65%) metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia (MCIH) repair. The rate of complications before discharge was 0.37%. There were no significantly differences in reoperation (aHR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.12–2.19) and complications (aOR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.17–4.11) between laparoscopic and open surgery. Age < 3 years (aHR = 6.40, 95%CI: 1.66–24.61), unilateral hernia (aHR = 11.09, 95%CI: 1.46–84.30), and anemia (aHR = 8.58, 95%CI: 1.94–38.05) were independent risk factors for reoperation. Obstruction/gangrene was independent risk factor for complications (aOR = 17.16, 95%CI: 4.07–72.38). Laparoscopic sac high ligation was most commonly performed in children < 13 years, and open and laparoscopic tension-free repairs were more frequently in those > 13 years. Both laparoscopic and open approaches were safe and effective, with low incidence of reoperations and complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inguinal hernia is one of the most common surgical condition, with more than 32 million inguinal hernia patients worldwide in 20191,2. The age distribution for inguinal hernia repair demonstrates bimodal peak at early childhood and old age, and inguinal hernia repairs are one of the most commonly performed pediatric operations3,4,5. In children, an inguinal hernia is thought to be caused by protrusion of the intestine into the unclosed processus vaginalis4. While in old adults, inguinal hernia is more likely due to weakening connective tissue and decreased abdominal wall resistance6. Inguinal hernia may be asymptomatic in some children, however, surgical repair is always necessary, as there is high risk of incarceration, involving bowel, testis, or ovary5,7,8.

There are significant differences in the surgical approach, technique, and treatment strategy of inguinal hernias between children and adults. In terms of the surgical approach, open inguinal hernia repair was reported to be the most performed and an excellent treatment strategy in children8,9. However, with the development of minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR) has progressed rapidly in the past decades6. In adults, LIHR is gradually increasing in countries such as Korea, Italy, and United States6,10,11. This same trend may present in the pediatric population6, although there is a lack of study concerning the different pattern of laparoscopic repairs in children and young adults.

In terms of the surgical techniques, hernia sac high ligation was the main surgical method in children, including intracorporeal and extracorporeal closing the internal ring6,12. While in adults, tension-free repair such as Lichtenstein repair was considered as the gold standard for inguinal hernia13. In addition, exploration and closure of contralateral patent processus vaginalis (CPPV) is still controversial in pediatric patients8. The surgical approach, technique and treatment strategy used for children varied dramatically between studies, which has great impact on hernia surgery outcomes. Long-term follow-up to evaluate the surgical outcomes after inguinal hernia repair in children was necessary.

In recent years, laparoscopic repair was also commonly adopted among adult inguinal hernia patients in China14. However, the surgical methods for inguinal hernia among children in specialized hernia center remains unclear. In addition, long-term follow-up results of laparoscopic and open repair of inguinal hernias in children are lacking. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the surgical methods of inguinal hernia repair among children, adolescents and young adults of different sex and age, and to compare surgical outcomes including reoperation and complications after laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair in a large hernia center in China.

Methods

Study design and data source

This is a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. We used the front sheet data of medical record of inguinal hernia inpatients between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2021 in the Department of Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, which is a large hernia center in Beijing, China. The front sheet data of medical record contained all admission records during the study period. Thus, patients with multiple admissions could be identified. The front sheet data included information of demographic characteristics, discharge diagnoses, and surgical procedures, which was obtained directly and in anonymous format from hospital information systems. Inguinal hernia, comorbidities, and postoperative complications during hospitalization were diagnosed and coded by surgeons according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Surgical methods were recorded by surgeons according to the 9th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9). This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University. The requirement for informed consent was waived by institutional review board of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study and the anonymous nature of the data.

Study population

Inclusion criteria for this study were children, adolescents and young adults with inguinal hernia who aged ≤ 25 years, and underwent initial inguinal hernia repair in the Department of Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2021. During the study period, we identified 19,084 admission records of inguinal hernia patients by ICD-10 codes of K40 in the main discharge diagnosis, including K40.0 (Bilateral inguinal hernia, with obstruction, without gangrene), K40.1 (Bilateral inguinal hernia, with gangrene), K40.2 (Bilateral inguinal hernia, without obstruction or gangrene), K40.3 (Unilateral or unspecified inguinal hernia, with obstruction, without gangrene), K40.4 (Unilateral or unspecified inguinal hernia, with gangrene), and K40.9 (Unilateral or unspecified inguinal hernia, without obstruction or gangrene). Firstly, we excluded 701 records with no surgery information. Then, the first admission record of every inpatient was included (n = 17739), of which 3252 were inpatients aged ≤ 25 years. After checking the surgical procedure codes, a further three inpatients received only laparoscopic exploration and no hernia repair were excluded. Eventually, a total of 3249 patients who received inguinal hernia repair were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Definition of surgical methods

Surgical methods were identified by ICD-9 codes of surgical procedures in the medical records. Surgical approaches were categorized as laparoscopic and open repair. Surgical techniques were categorized as hernia sac high ligation (laparoscopic or open), and tension-free repair. After combining the above two classification standards, surgical methods were further categorized as four group: laparoscopic sac high ligation, laparoscopic tension-free repair, open sac high ligation, and open tension-free repair.

Outcomes

The main outcome of interest was reoperation for inguinal hernia. A second inguinal hernia repair at the same hernia center after the initial inguinal hernia surgery was identified and considered as reoperation. In this study, reoperation included operation for ipsilateral recurrence and operation for metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia (MCIH), which was identified by reviewing the medical records of the initial and the second operation. There were some patients with bilateral hernia whose hernia repair surgery was performed in two sessions. For these patients, the second operation was not considered as reoperation.

Secondary outcome was postoperative complications diagnosed before discharge. Postoperative complications assessed in this study included complications of procedures (T81), infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (L00-L08), symptoms and signs involving the circulatory and respiratory systems (R00-R09), metabolic disorders (E70-E90), coagulation defect (D68.9).

In this study, all participants were followed from the admission date of the initial inguinal hernia repair to the date of a second inguinal hernia repair, or until the follow-up ceased (June 30, 2022), whichever came first.

Covariates

The demographic and clinical characteristics were collected as covariates, including: sex, age (< 3 years, 3–9 years, 10–19 years, 20–25 years), indirect hernia (yes or no), emergency surgery (yes or no). Bilateral hernia, history of groin surgery, obstruction or gangrene, and comorbidities (including thrombocytosis, dyslipidemia, anemia, elevated blood glucose level) were identified by ICD-10 codes: bilateral hernia (K40.0-K40.2), history of groin surgery (Z98.8606), obstruction or gangrene (K40.0, K40.1, K40.3, K40.4), thrombocytosis (D75.201), dyslipidemia (E78), anemia (D64.902), elevated blood glucose level (R73).

Statistical analysis

Age was described by median and interquartile range (IQRs). Categorical variables were described as proportions. The distribution of surgical methods was presented according to eight age groups: 0–3 years, 4–6 years, 7–9 years, 10–12 years, 13–15 years, 16–18 years, 19–21 years, and 22–25 years. We calculated the overall cumulated incidence of reoperation and complications. For patients who underwent reoperation, we described their clinical characteristics at the time of initial surgery, cause of reoperation (ipsilateral recurrence, MCIH), and time from initial surgery to reoperation. The incidence of ipsilateral recurrence and MCIH was calculated as well. χ2 test was used to compare the distribution of characteristics, incidence of reoperation and MCIH between different patients. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression models were used to analyze the association of surgical methods and reoperation, and to estimate crude hazard ratio (cHR), adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI). The association of surgical methods and MCIH was also analyzed. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to analyzed the association of surgical methods and complications, and to estimate crude odds ratio (cOR), adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and their 95% CIs. Surgical approach and techniques, age, sex, and other baseline characteristics which were significant in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. All analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Two-sided p values < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of study population

The demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by sex were present in Table 1. Of the 3249 patients included in the final analysis, 2587 (79.62%) were male, the median age was 5 years (IQR: 2–11 years). The proportion of patients aged < 3 years, 3–9 years, 10–19 years, and 20–25 years was 29.36%, 43.46%, 14.10%, and 13.08%, respectively. Male patients were more likely to be infants younger than 3 years (34.33% vs. 9.97%), have unilateral hernia (68.61% vs. 63.60%), have obstruction or gangrene (1.28% vs. 0.30%), have groin surgery history (5.64% vs. 1.81%) than female patients. The prevalence of dyslipidemia (2.36% vs. 1.06%), anemia (1.35% vs. 0.30%), and elevated blood glucose level (1.01% vs. 0.15%) was significantly higher in male patients than in female patients.

Surgical methods by sex and age groups

A total of 2638 patients (81.19%) underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 611 (18.81%) underwent open surgery. Sac high ligation was performed in 2421 patients (74.52%) and tension-free repair was performed in 828 (25.48%) patients. Laparoscopic sac high ligation was the most common surgical methods in both male (73.87%) and female patients (69.18%). The distribution of different surgical methods according to age groups were present in Fig. 2. Laparoscopic surgeries were most commonly performed among infants aged ≤ 3 years (97.95%), and decreased with the increasing age, reached the lowest in adolescents aged 13–15 years (15.24%). Laparoscopic sac high ligation was most common among infants and children who were younger than 13 years (from 61.11% in 10–12 years old to 96.77% in 0–3 years old). Open and laparoscopic tension-free repairs were more frequently among adolescents and young adults older than 13 years (from 92.38% in 13–15 years old to 100% in 19–21 years old, Table 2; Fig. 2).

Reoperations and complications

During a median follow-up of 51.91 months (IQR: 33.84–71.03), 26 patients received a second surgery, two of which received the second surgery for bilateral hernia. Thus, 24 out of 3249 (0.74%) patients underwent reoperation, including 3 (0.09%) ipsilateral recurrence, and 21 (0.65%) MCIH repair. Of all patients received reoperation, 21 (87.50%) were male, 15 (62.50%) had reoperation for right inguinal hernia repair. The median time from initial surgery to reoperation was 12.57 months (IQR: 9.96–22.16). At the time of initial surgery, 12 (50.00%) were aged < 3 years, one (4.17%) had initial bilateral hernia, 14 (58.33%) underwent laparoscopic sac high ligation, 8 (33.33%) had open tension-free repair, and 2 (8.33%) had laparoscopic tension-free repair. 23 patients received the same surgical methods for reoperation and the initial operation, except one patient received initial laparoscopic sac high ligation and subsequent open tension-free repair for reoperation.

Of the 3249 patients, 12 (0.37%) patients had postoperative complications before discharge, all of them were male patients. 5 (0.15%) had complications of metabolic disorders, 4 (0.12%) had symptoms and signs involving the circulatory and respiratory systems, 3 (0.09%) had complications of procedures, and 2 (0.06%) had coagulation defect. No infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue were detected during the hospital stays in all participants.

Association between surgical methods with reoperation and complications

The incidence of reoperation was 1.31% in open and 0.61% in laparoscopic group, 1.21% in tension-free and 0.58% in sac high ligation group, with no significant differences between groups. Results of univariable analysis showed that the reoperation incidence was significantly higher in infants < 3 years and young adults aged between 20 and 25 years, patients with unilateral hernias, and patients with anemia. Results of multivariable Cox regression showed that < 3 years (aHR = 6.40, 95%CI: 1.66–24.61), unilateral hernia (aHR = 11.09, 95%CI: 1.46–84.30), and anemia (aHR = 8.58, 95%CI: 1.94–38.05) were independent risk factors for reoperation. There were no significantly differences of reoperation between laparoscopic and open surgery (aHR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.12–2.19), or between sac high ligation and tension-free repair (aHR = 2.83, 95%CI: 0.35–22.75, Table 3). We also analyzed the association between surgical methods and MCIH. The incidence of MCIH was significantly higher in open than in laparoscopic group (1.31% vs. 0.49%, p = 0.047), and higher in tension-free than in sac high ligation group (1.21% vs. 0.45%, p = 0.020). However, there was no significant difference between open and laparoscopic group after adjusting for sex, age groups, and surgical techniques in multivariable analysis (aHR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.13–1.75).

The complications rate was significantly higher in open than in laparoscopic group (0.98% vs. 0.23%, p = 0.016), and significantly higher in tension-free than in sac high ligation group (0.97% vs. 0.17%, p = 0.003). Results of univariable analysis showed that the complications rate was significantly higher in patients aged between 10 and 25 years, and those with obstruction/gangrene. Results of multivariable logistic regression showed that obstruction/gangrene was independent risk factor for complications (aOR = 17.16, 95%CI: 4.07–72.38). There were no significantly differences of complications between laparoscopic and open surgery (aOR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.17–4.11), or between sac high ligation and tension-free repair after controlling for age group and obstruction/gangrene (aOR = 2.82, 95%CI: 0.16–48.76, Table 4).

Discussion

In this hospital-based cohort study, we present our experience of inguinal hernia repair in children, adolescents, and young adults between 2015 and 2021, aiming to analyze the surgical methods and evaluate the surgical outcomes of laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repairs. We found that laparoscopic sac high ligation was most commonly performed among infants and children who were younger than 13 years, while open and laparoscopic tension-free repairs were more frequently among adolescents and young adults older than 13 years. The incidence of reoperation and complications were 0.74% and 0.37%, which were comparable between laparoscopic and open surgery groups. Our results suggested that both laparoscopic and open surgeries were equally acceptable for inguinal hernia repairs among pediatric patients, with low incidence of reoperation and minimal complications.

In the present study, we found that laparoscopic repair was commonly performed in pediatric inguinal hernias, especially among infants and children who were younger than 13 years. Throughout the past two decades, laparoscopy has come to prominence as an alternative approach to pediatric inguinal hernia repair15. Overall, LIHR was performed in over 80% of patients aged younger than 25 years in our study, which was more commonly than 49% in adult inguinal hernia patients in our previous study14. Laparoscopic repairs have become the mainstream for children in our hernia center. This benefits from the sufficient equipment and experienced surgeons in large volume hernia center. On the contrary, open inguinal hernia repairs still dominant in children in United States and German, although laparoscopic repair is increasingly used in these countries16,17. The advantages of LIHR in children included closure the deep ring under direct vision, high-definition visualization of vas deferens or the spermatic vessels, and reduced tissue trauma to these structures12,18. At the same time, surgeons could visualize the contralateral internal inguinal ring and repair contralateral hernias, which has the potential of eliminating the risk of a metachronous hernia developing12.

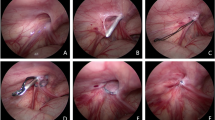

In terms of the surgical techniques, we found that laparoscopic or open sac high ligation was mainly used for infants and children. In our center, laparoscopic sac high ligation was performed under the assistance of a needle-type grasper and using extracorporeal suture repair with the knot buried subcutaneously, which was simple and rapid15,19. A 5 mm incision was made within the umbilicus for trocar, and two 1.5 mm skin incision was made for needle-type grasper and endo-closure device19. The single 5 mm trocar site scar was hidden very nicely within the umbilicus, and reduced the risk of scar infection for infants15. For infants and younger children, the scar after open inguinal hernia repair was located into the diaper with a high risk of contamination15,20. While after LIHR, there was a lower incidence of scar infections in patients under 2 years of age, as the umbilical scar after laparoscopic repair was outside the diaper coverage area9. In the present study, no infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue were detected during the hospital stays in all patients.

In our study, we found that tension-free repair gradually increased with the increasing age, and became the most commonly used techniques for adolescents and young adults older than 13 years. For children aged older than 13 years who had large hernia defect (> 2.5 cm), or those with slow or finished growth of abdominal wall, or those with high risk of increased abdominal pressure, simple sac high ligation was no longer appropriate19,21. These patients were treated with mesh to repair the transverse fascia, strengthen the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, so as to minimize recurrence19.

The evidence published to date comparing open versus laparoscopic surgery supports that recurrence rates are similar between the two methods12. A systematic review including ten studies with 1270 patients found no differences in recurrence rate and complications between laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair in children under 18 years22. In this study, we compared the incidence of reoperation after laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair, and no significant difference was found in our cohort. Reoperation rate was low in our cohort, which was 0.61% in laparoscopic and 1.31% in open surgery. Only three ipsilateral recurrences were observed in this study, with a recurrence rate of 0.09%, which was lower than the recurrence rate between 0.5% and 6.0% published by previous studies21,23. Our results suggested that both laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repairs were effective for children and young adults younger than 25 years.

In the present study, we found that most patients received reoperation for MCIH. The incidence of MCIH was significantly higher in open than in laparoscopic group (1.31% vs. 0.49%). However, multivariable analysis showed that there was no significant difference between open and laparoscopic surgery after adjusting for sex, age, and surgical techniques. The reduced incidence of MCIH after LIHR was observed in previous studies23,24, which was against the results of multivariable analysis in our study. Safa et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study including 1952 patients and found that LIHR in children resulted in a decrease in the incidence of MCIH compared to open surgery, since a contralateral PPV was always closed during LIHR in their study24. Wu et al. included 2059 children with inguinal hernia, and found that the incidence rate of MCIH was reduced from 3.7% in open repair to 0.3% in LIHR after performing prophylactic ligation of CPPV23. There is a lack of studies in the literature with findings similar to our study, future analyses remain necessary. In our center, we also performed routine contralateral exploration and closed the CPPV, which might contribute to the low incidence of MCIH in this study. However, contralateral exploration and closure of asymptomatic PPV remains controversial in pediatric patients23,25. Evidence indicated that routine repair of CPPV reduced the rate of subsequent MCIH, but 21 contralateral PPVs needed to be closed to prevent one MCIH25. There is concern that a routine repair may result in overtreatment25. We can assume that closing of CPPV can prevent development of an MCIH8, but further study is necessary to evaluated the benefits and risks of this strategy.

In this study, we found that age < 3 years old, uniliteral hernia, and anemia were independent risk factors for reoperation. The risk of reoperation in infants younger than 3 years was 6 times higher than in children aged 3–9 years old. This might be due to the narrowing or obliterating of PPV as children grow older26. In addition, patients with initial unilateral hernia repair had higher risk of operation than those with bilateral hernias, and more than 60% of patients had reoperation for right-sided inguinal hernias. This might because that the left testis descends before the right and commonly closes first, resulting in a higher incidence of right-sided inguinal hernias in boys27. Therefore, children with initial left-sided hernia might have higher risk of reoperation for a contralateral hernia27. Children with anemia was also identified as high-risk patients for reoperation in this study. This was similar to previous study showed that anemia was a significant risk factor for unfavorable postoperative outcome in patients undergoing general surgery28. Since anemia is a modifiable risk factor, it should be corrected before surgery to improve surgical outcomes28. Our findings suggested that infants younger than 3 years and those with unilateral hernias might benefit more from routine CPPV exploration and closure, and parents needed to be appropriately counselled before surgery29.

Obstruction or gangrene was found to be the only independent risk factor for in-hospital complications in our study. It was reported that infants younger than one years had an incidence of 13.28% for incarcerated hernia, which was associated with higher risk of longer operative time, hospital stay and higher hospital costs26. Thus, we assumed that earlier repair of elective hernias to minimize the risk of obstruction might reduce subsequent complications. However, most inguinal hernias are asymptomatic in children, and they are often found during routine physical examination or when incarcerated, especially for infants who are unable to communicate the presence of an inguinal hernia26,27. Therefore, parents should pay attention to signs and symptoms related to inguinal hernia and incarceration, including sudden appearance of a bulge in the inguinal region or scrotum/labia during diaper change or after bathing, and obstructive symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, lack of bowel function, and abdominal distention20,27.

Our study has several limitations. First, some factors might be related with reoperation were not available from the front sheet of medical records, such as the laterality, size, and classification of inguinal hernia. These factors could not be controlled in this study, which might bias our results. Second, some patients with recurrence might not go back to our center for reoperation due to various reasons. Thus, the reoperation rate might be underestimated. Third, long-term postoperative complications were not captured by front sheet data of medical record. Only complications recorded before discharge were analyzed in this study. Despite this, this study covered a 7-year period, which provided us with valuable information about the surgical methods and surgical outcomes for laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repairs. All patients younger than 25 years old who received inguinal hernia repair between 2015 and 2021 were included. The different surgical methods of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults were systematically analyzed. Meanwhile, the median follow-up was 51.91 months in this study. This long-term follow-up enabled us to detect the relatively rare recurrence and MCIH of inguinal hernia repairs.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic hernia sac high ligation was most commonly performed among infants and children younger than 13 years, and open and laparoscopic tension-free repairs were more frequently among adolescents and young adults older than 13 years. Both laparoscopic and open repairs were safe and effective, with low incidence of reoperations and complications.

Data availability

The data associated with the paper are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Öberg, S. & Rosenberg, J. Contemporary inguinal hernia management. Br. J. Surg. 109 (3), 244–246 (2022).

Ma, Q. et al. The global, regional, and National burden and its trends of inguinal, femoral, and abdominal hernia from 1990 to 2019: findings from the 2019 global burden of disease Study - a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Surg. 109 (3), 333–342 (2023).

McBee, P. J., Walters, R. W. & Fitzgibbons, R. J. Current status of inguinal hernia management: A review. Int. J. Abdom. Wall Hernia Surg. 5 (4), 159–164 (2022).

Watanabe, T. et al. Asymptomatic patent processus vaginalis is a risk for developing external inguinal hernia in adults: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 64, 102258 (2021).

Wolf, L. L. et al. Epidemiology of abdominal wall and groin hernia repairs in children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 37 (5), 587–595 (2021).

Han, S. R. et al. Inguinal hernia surgery in Korea: nationwide data from 2007–2015. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 97 (1), 41–47 (2019).

Morini, F. et al. Surgical management of pediatric inguinal hernia: A systematic review and guideline from the European pediatric surgeons’ association evidence and guideline committee. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 32 (3), 219–232 (2022).

Dreuning, K., Maat, S., Twisk, J., van Heurn, E. & Derikx, J. Laparoscopic versus open pediatric inguinal hernia repair: state-of-the-art comparison and future perspectives from a meta-analysis. Surg. Endosc. 33 (10), 3177–3191 (2019).

Esposito, C. et al. Twenty-year experience with laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in infants and children: considerations and results on 1833 hernia repairs. Surg. Endosc. 31 (3), 1461–1468 (2017).

Ortenzi, M. et al. Nationwide analysis of open groin hernia repairs in Italy from 2015 to 2020. Hernia 27 (6), 1429-1437 (2023).

Holleran, T. J. et al. Trends and outcomes of open, laparoscopic, and robotic inguinal hernia repair in the veterans affairs system. Hernia 26 (3), 889–899 (2022).

Davies, D. A., Rideout, D. A. & Clarke, S. A. The international pediatric endosurgery group Evidence-Based guideline on minimal access approaches to the operative management of inguinal hernia in children. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 30 (2), 221–227 (2020).

Hakan Kulacoglu. Some more time with an old friend: small details for better outcomes with Lichtenstein repair for inguinal hernias. Int. J. Abdom. Wall Hernia Surg. 5 (4), 221–228 (2022).

Ma, Q., Liu, X., Yang, H., Gu, L. & Chen, J. Utilization of laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair at a large hernia center in China: a single-center observational study. Surg. Endosc. 37 (2), 1140–1148 (2023).

Grech, G. & Shoukry, M. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in children: Article review and the preliminary Maltese experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 57 (6), 1162–1169 (2022).

Shaughnessy, M. P., Maassel, N. L., Yung, N., Solomon, D. G. & Cowles, R. A. Laparoscopy is increasingly used for pediatric inguinal hernia repair. J. Pediatr. Surg. 56 (11), 2016–2021 (2021).

Heydweiller, A., Kurz, R., Schröder, A. & von Oetzmann, C. Inguinal hernia repair in inpatient children: a nationwide analysis of German administrative data. BMC Surg. 21 (1), 372 (2021).

Jin, Y., Zhang, Y. B., Chen, K. & Gao, Z. G. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of incarcerated indirect inguinal hernia in children. Asian J. Surg. 45 (7), 1489–1490 (2022).

Chu, C. B. et al. Individualized treatment of pediatric inguinal hernia reduces adolescent recurrence rate: an analysis of 3006 cases. Surg. Today. 50 (5), 499–508 (2020).

Esposito, C. et al. Current concepts in the management of inguinal hernia and hydrocele in pediatric patients in laparoscopic era. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 25 (4), 232–240 (2016).

Lobe, T. E. & Bianco, F. M. Adolescent inguinal hernia repair: a review of the literature and recommendations for selective management. Hernia 26 (3), 831–837 (2022).

Olesen, C. S., Andresen, K., Öberg, S. & Rosenberg, J. Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernias in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Endosc. 33 (7), 2050–2060 (2019).

Wu, S. et al. Comparison of laparoscope-assisted single-needle laparoscopic percutaneous extraperitoneal closure versus open repair for pediatric inguinal hernia. BMC Surg. 22 (1), 334 (2022).

Safa, N. et al. Open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in children: A regional experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 58 (1), 146–152 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Potential value of routine contralateral patent processus vaginalis repair in children with unilateral inguinal hernia. Br. J. Surg. 104 (1), 148–151 (2017).

Wang, K. et al. Characteristics and treatments for pediatric ordinary and incarcerated inguinal hernia based on gender: 12-year experiences from a single center. BMC Surg. 21 (1), 67 (2021).

Abdulhai, S. A., Glenn, I. C. & Ponsky, T. A. Incarcerated pediatric hernias. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 97 (1), 129–145 (2017).

Braunschmid, T. et al. Prevalence and long-term implications of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing elective general surgery - a retrospective cohort study at a university hospital. Int. J. Surg. 110 (2), 884-890 (2024).

Yeap, E., Pacilli, M. & Nataraja, R. M. Inguinal hernias in children. Aust J. Gen. Pract. 49 (1–2), 38–43 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QM searched the literature, designed the study, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. XL, ZZ, CL, JC, and HY collected the data and revised the manuscript. YS conceived the study, designed the study, supervised the study, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital. The requirement for informed consent was waived by institutional review board of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study and the anonymous nature of the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Q., Liu, X., Zou, Z. et al. Surgical methods and outcomes of inguinal hernia repair in children, adolescents and young adults in a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 9220 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93841-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93841-5