Abstract

Adolescents develop rapidly, are sensitive to external environmental pressure, and are prone to depression symptoms. Physical activity has been identified as a protective factor for depressive symptoms. Psychological capital is strongly associated with depressive symptoms, and gender has been identified as a potential protective factor. For adolescents in early adolescence, the complex relationship between these factors needs further study. The aim of this study was to explore the mediating role of psychological capital between depressive symptoms and physical activity in adolescents, and the moderating role of gender between the two. Physical activity, depressive symptoms and psychological capital were measured by Physical Activity Rating Scale (par-3), Central Depression Scale (CES-D) and Psychological Capital Scale (PCQAS) in 1146 adolescents. The proposed relationships were tested using models 4 and 14 of the structural equation model, respectively, for mediating and regulating effects. Physical activity was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms and positively correlated with psychological capital. Psychological capital was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms and mediated the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms. Gender effectively modulates the latter half of the mediated model pathway. In adolescents, especially girls, depression symptoms can be alleviated and prevented by increasing daily physical activity and positive psychological capital reserve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduce

Worldwide, depression is one of the most common mental health problems1and a major cause of harmful behaviors such as disability and suicide. According to the Blue Book of National Depression Symptoms 2022, the number of depression cases among adolescents under the age of 18 accounts for 30.28% of the overall prevalence rate2. As a special period of individual development, adolescents not only have to face a series of changes in physical and mental development, but also bear greater academic pressure and are more prone to mental health problems such as depression3.In addition, the onset of adolescent disease will carry a high risk of recurrence and the threat of functional dysplasia throughout the future life cycle1. Depressive symptoms refer to the abnormal feelings and states shown by the body due to depression, including low mood, loss of interest, loss of pleasure, memory decline, retarded thinking, and accompanied by sleep and eating disorders4, which belong to the subclinical state of depression and have strong concealment, which may lead to individual depression in the long run. Symptoms such as inability to live and study normally and increased aggressive behavior may persist into adulthood5. The study shows that by 2021, the detection rate of depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents will reach 24.1%6, while the detection rate of depressive symptoms in rural areas is 33.9%, higher than that in urban areas (27.5%)7, and the trend is rising year by year, causing serious negative impact on individuals, families and society8,9. Therefore, it is of great significance to pay attention to depression in rural adolescents.

Preventing the occurrence of depressive symptoms and altering the identified risk factors, thereby preventing the further development of depressive symptoms, requires effective interventions. One prospective study reported that people with high levels of physical activity were 17% less likely to develop depression compared to people with low levels of physical activity10. Physical activity refers to any physical action that consumes energy generated by skeletal muscle contraction11. Adequate physical activity can relieve anxiety12,87,88,89,16, depression, stress17, tension and other adverse psychological problems, and is an important protective factor for depressive symptoms in individuals with high genetic susceptibility to depression18. The mechanism of physical activity inhibiting the occurrence of depressive symptoms is complicated, but most studies believe that it is related to psychosocial factors, which believe that engaging in physical activity can help improve the social support network, provide opportunities for individuals to participate in social interaction and socializing19, and buffer depressive symptoms20. In exercise psychology, relevant scholars have put forward many hypotheses on the benefits of physical activity to mental health, one of which is the social interaction hypothesis21. According to the social interaction hypothesis, physical activities that individuals participate in are mostly social activities, which are conducive to increasing interpersonal communication, regulating their behaviors and emotions22, and continuously improving people’s social support23. With the improvement of social support level, individuals’ negative emotion can be alleviated24and their mental function can be promoted25,26. Participation in physical activity is a proven effective strategy to prevent mental health problems27,28,29. More and more evidence shows that physical activity is negatively correlated with depression, indicating that adolescents who engage in higher moderate to vigorous physical activity tend to have fewer depressive symptoms30,31. Participation in physical activity continuously increases the release of endorphins. Thus improving mood32, to achieve the purpose of improving mental health33. Meta-analysis has also shown that increasing physical activity can be used as a therapeutic intervention to prevent and alleviate depression in adolescents34,22,36. Compared with people who did not engage in physical activity, those who exercised the equivalent of 2.5 h of brisk walking per week were 25% less likely to develop depression, and 1.25 h of exercise per week was associated with an 18% lower risk37. Regardless of age and sex, the more physically active people were, the lower the risk of depression38. Although physical activity is beneficial to health39, previous studies have shown that only one third of adolescents in China have reached the time of one hour of physical activity per day40, and the incidence of depression is on the rise year by year41, and the detection rate of depressive symptoms is much higher than that of Japan, France and other regions42.

From the perspective of positive psychology, the positive psychological characteristics of individuals can, to a certain extent, prevent the negative impact of adverse external environment on individuals43and experience less psychological pressure. Individuals with more positive psychological resources will have a higher sense of happiness and a good state of happiness44. As an important internal psychological resource, psychological capital is a positive psychological resource in the process of individual growth and development, mainly including four parts: self-efficacy, resilience, hope and optimism45. Psychological capital can help individuals invoke positive psychological resource reserves to effectively alleviate or even eliminate the troubles and pains caused by the adverse external environment46. The research results show that physical activity is one of the important influencing factors for the improvement of psychological capital. Participation in physical activity can affect individual self-esteem, self-efficacy and positive emotions47and improve the level of psychological capital. According to the social conflict theory, physical activity plays the role of a safety valve and a pressure reducer. Exercise can eliminate the emotional blockage of individuals, release the aggressive instinct of individuals, cultivate individual positive emotions, and improve the reserve of positive psychological capital48. Among the various factors that affect individual mental health, more and more attention has been paid to the positive effects of physical activity. In the process of engaging in physical activities, individuals can develop positive psychological qualities such as self-efficacy, self-confidence and resilience49, and the reserve of positive psychological capital increases with the increase of physical activities, and can maintain a relatively stable state of happiness of individuals50. High psychological capital is closely related to positive emotions51. Individuals with high psychological capital tend to have strong psychological resilience52. When faced with changes and stimuli of the external environment, they will show more positive emotional tendencies, which helps to build lasting positive personal resources, relieve bad emotions, and correctly face external difficulties and challenges. Long-term adaptive benefits to individuals53. At the same time, high psychological capital has a compensatory effect on adolescents’ adaptation, which can offset the influence of cumulative risks such as family economic pressure and peer rejection on depression to a certain extent43. Studies have found that adolescents not only have to consume positive psychological resources to deal with the pressure brought by physical and mental development, but also have to deal with the accumulated pressure events from family, society and school. Too much pressure makes them unable to better experience the meaning of life. The performance of adolescent students in the four dimensions of psychological capital (self-efficacy, resilience, hope and optimism) is poor54, showing a significant negative correlation with depression, that is, the lower the level of individual psychological capital, the more depressed the adolescent will feel55.

Gender is an important demographic factor affecting physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents, and the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms may differ between boys and girls. After entering middle school, with the increase of learning demand56, academic pressure and individual static learning time, the time and frequency of participating in sports activities show a downward trend. At the same time, relevant studies have shown that the physical activity of children and adolescents is closely related to gender, and the physical activity level of boys is significantly higher than that of girls57, and the physical activity level of girls shows a significant downward trend from adolescence58,59. The gendered family process model points out that gender-differentiated parenting plays an important role in the cultivation of adolescent behavior, and parents adopt different parenting strategies for boys and girls, which leads to the difference in the development of boys and girls60. Influenced by the concept of family education, girls are more susceptible to cues from the external environment61, resulting in lower levels of physical activity than boys. Studies have shown that adolescents who participate in too little physical activity have a higher detection rate of depressive symptoms than adolescents who participate in physical activity regularly, and the detection rate is62,63higher in girls than in boys. This may be related to the fact that girls, starting from early adolescence, have higher stress levels than boys, have higher levels of negative emotion perception than boys, and are susceptible to negative emotions64, which leads to the aggravation of depressed mood and depressive symptoms65. At the same time, compared with girls, boys’ social adaptability is stronger, self-confidence is stronger, psychological capital score is much higher than girls66. The study found that the degree of physical activity participation was positively correlated with psychological capital67, and pointed out that physical activity had an important predictive effect on psychological capital68. Longitudinal studies have also shown that regular physical exercise can promote higher levels of self-esteem and positive psychology, and gain more competitive advantage in psychological capital69. This suggests that gender may play an important role between physical activity, depressive symptoms, and psychological capital, which needs to be addressed in research and practice.

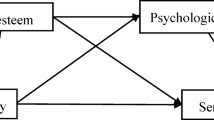

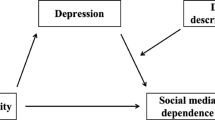

In conclusion, depressive symptoms have become an important risk factor for adolescents’ mental health. Physical activity and psychological capital are associated with depressive symptoms, but the intrinsic relationship between these variables and the moderating role of gender have not been fully studied. In addition, as a positive internal resource that individuals can cultivate and shape, psychological capital has been relatively lacking in previous studies focusing on this variable and its correlation. Therefore, this study took adolescents as the research object to explore the relationship between physical activity, psychological capital and depressive symptoms, as well as the regulatory role of gender between psychological capital and depressive symptoms, so as to provide reference for the alleviation and prevention of depressive symptoms in students of different genders. Therefore, we developed a moderated mediation model (see Fig. 1) and proposed three hypotheses: (1) Physical activity negatively predicts adolescent depressive symptoms; (2) Psychological capital plays a mediating role in the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents; (3) Gender plays an important role in the second half of the mediation model between physical activity and adolescent depressive symptoms.

Methods

Study population

Before participating, the researchers explained the purpose of the study to all participants and assured them of the confidentiality of the questionnaire. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the survey. The questionnaires were distributed and collected anonymously with the assistance of the class teacher. A cluster stratified random sampling method was adopted to randomly select three middle schools from public schools in western Hunan, and then randomly select three classes from grades 7 to 9 from the three middle schools, and select all middle school students from 27 classes as the research objects. The sample size is calculated as n = µ < s:2 > 2 × [π× (1-π)] /δ2. µ2 = 1.96 (95% confidence interval) and χ = 0.05, so the tolerable error δ was 0.05,π = 40.67%(According to previous surveys on depressive symptoms in adolescents, the incidence of depressive symptoms in adolescents ranged from 14.92 to 40.67%), so the sample size for each group was n = 190. Consider that the population comes from 3 different junior high schools, each junior high school grouped by grade and gender, N = n×3 × 2 = 1140 people. In addition, due to the uncertainty of class size and other reasons (such as leave, etc.), a total of 1176 students completed the questionnaire, of which 541 (47.21%) boys and 605 (52.79%) girls completed the questionnaire. Thirty students were excluded from the analysis because they completed the survey within 120 s, had incomplete data or had similar responses to all items. The data of the remaining 1146 students were included in the analysis, and the effective response rate was 97.45%. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Jishou University.

Measurement

Physical activity

Physical activity (PA) was measured using the revised PARS-3 developed by Liang Deqing et al.70. It assesses the subjects’ exercise based on intensity, frequency, and duration, with a scale divided into 5 levels, scoring from 1 to 5. The total exercise score is calculated as exercise intensity × (duration − 1) × frequency, with a range of 0 to 100 points. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.721.

Depression symptoms

The Depression Scale (CES-D) was used by the epidemiology center to assess individuals’ depression levels over the past week71. The scale consists of 20 items covering depression, positive mood, somatic symptoms and activity retardation, and interpersonal relations, scored from 0 (rarely or none) to 3 (most of the time), with items 4, 8, 12, and 16 scored reversely. The total score ranges from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater depression symptoms. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.859.

Psychological capital

The “Psychological Capital Questionnaire for Adolescents (PCQAS)” compiled by Fang Bijie72 was used to investigate psychological capital among middle school students. The scale has 22 items divided into hope, optimism, confidence, and resilience, scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with items 3, 7, 11, and 15 scored reversely. The total score ranges from 22 to 132, with higher scores indicating greater psychological capital. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.916.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics such as age and gender were collected as covariates.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0, with significance set at P< 0.05 (two-tailed). Normality was assessed using normality tests; according to Kim’s recommendations, data with absolute skewness less than 2 and absolute kurtosis less than 7 are considered approximately normally distributed73. Harman’s single-factor test was then conducted to evaluate common method bias, with a threshold below 40% indicating no significant common method bias74. Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore correlations among physical activity, depression symptoms, and gender. Moderated mediation analysis was conducted using SPSS PROCESS (Model 14)75 to examine the relationship between physical activity and depression symptoms among rural middle school students, investigating the mediating role of psychological capital and the moderating role of gender. Finally, 5000 bootstrap resampling iterations were used to assess model fit and estimate the 95% confidence interval (95% CI), ensuring stability in data analysis while controlling for age and gender as covariates.

Results

General information of participants

A total of 1146 students (14.076 ± 0.959) completed the questionnaire and were included in the analysis. Among them, 541 were boys (47.21%) and 605 were girls (52.79%); 386 were in grade 7 (33.68%), 374 in grade 8 (32.64%), and 386 in grade 9 (33.68%); 241 were Han (21.03%), 458 were Miao (39.97%), 438 were Tujia (38.21%), and 9 were from other ethnic groups (0.79%).

Common method bias test

To avoid common methodological bias, Harman’s single-factor test was used. The results indicated that 7 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor accounting for 26.03% of the variance, far below the 40% critical value. Therefore, common method bias was ruled out as influencing the study results.

Correlation analysis of physical activity, psychological capital, and depression symptoms in rural middle school students

The correlation analysis revealed the following (see Table 1): Physical activity was significantly negatively correlated with depression symptoms and positively correlated with psychological capital. Depression symptoms were significantly negatively correlated with psychological capital. This indicates that greater participation in physical activity is associated with higher psychological capital and fewer depression symptoms. Specifically, physical activity and depression symptoms had a negative correlation (r = -0.112, p < 0.001) with statistical significance; physical exercise and psychological capital had a positive correlation (r = 0.211, p < 0.001) with statistical significance; and depression symptoms and psychological capital had a negative correlation (r = -0.518, p < 0.001) with statistical significance. These findings support the next step of mediating model testing.

Mediation analysis

In this study, physical activity was used as the independent variable, depressive symptoms as the dependent variable, psychological capital as the mediating variable and age, accommodation, only child, left-behind, family structure and gender as the controlling variables, this study explored the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms of rural middle school students. The results are shown in Table 2. Physical activity positively predicted psychological capital of rural middle school students (β = 0.279, SE = 0.040, p < 0.001), and negatively predicted depressive symptoms (β = -0.042, SE = 0.018, p < 0.05). When psychological capital was used as the mediating variable, psychological capital significantly negatively predicted depressive symptoms (β = -0.234, SE = 0.012, p < 0.001), while physical activity had no significant direct effect on depressive symptoms (β = -0.024, SE = 0.016, p > 0.05). The Bootstrap test with modified bias shows that psychological capital has a significant intermediary effect, with an indirect effect of -0.066 and a 95% confidence interval of [-0.086,-0.046]. The direct effect of physical exercise is not significant, the direct effect value is 0.024, and the 95% confidence interval is [-0.008, 0.055]. These results suggest that psychological capital plays a complete mediating role in the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms in rural middle school students (see Table 3). Figure 2 shows the mediating model pathway of psychological capital in the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms.

Moderation analysis of gender in the mediation effect

To further investigate whether the mediating role of psychological capital between physical activity and depressive symptoms is mediated by gender, we introduced a moderating variable. The results showed that psychological capital significantly predicted depressive symptoms when gender was the moderating factor (β = -0.086, SE = 0.036, p < 0.05). In addition, gender significantly predicted depressive symptoms in adolescents (β = 11.579, SE = 1.844, p < 0.001). The interaction term of psychological capital and gender also had a significant negative effect on depressive symptoms (β = -0.100, SE = 0.023, p < 0.001), with an index value of -0.028 and a 95% confidence interval of [-0.044,-0.014], excluding zero (see Table 4).

To explore the substantive interaction effect of psychological capital and gender, a simple slope analysis was performed. Psychological capital was categorized into high and low groups based on one standard deviation above and below the mean. Interaction effect plots were generated for different genders (see Fig. 3). The results indicate that, in the boy adolescent group, psychological capital significantly negatively predicts depressive symptoms (simple slope = -0.185, t = -11.531, p < 0.001). Similarly, in the girl adolescent group, psychological capital also significantly negatively predicts depressive symptoms (simple slope = -0.285, t = -17.562, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that higher psychological capital is associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms.

Discussion

This study focuses on the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents, and attempts to reveal the possible mediating and regulating mechanisms between physical activity and depressive symptoms. The results show that physical activity is negatively correlated with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Psychological capital completely mediates the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms. In addition, gender played a regulating role in the relationship between psychological capital and depressive symptoms. Compared with girls, boy adolescents were less affected by psychological capital and showed a lower level of depressive symptoms. The adolescent girls were more affected by psychological capital and showed a higher level of depressive symptoms. The results show that in order to prevent depression and depressive symptoms in adolescents, we should not only emphasize the importance of participating in physical activities in daily life, but also cultivate a positive attitude towards life and constantly improve the level of psychological capital.

First, physical activity levels were negatively associated with and negatively predicted depressive symptoms in adolescents. This result is consistent with hypothesis 1 and previous research results76.With the increase of physical activity, adolescents are less likely to develop depressive symptoms, indicating that active participation in physical activity and physical exercise can reduce the risk of developing depressive symptoms77,78. Rothon et al.79found an association between physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents, with each additional hour of physical activity associated with an 8% reduction in the risk of depressive symptoms. Studies have shown that excitement can be transmitted from the brain to the muscles, and the muscles can also transmit excitement to the muscles, so that the degree of excitement in the brain is increased and people’s emotions are high80. The dispersion hypothesis holds that active participation in physical activities can provide adolescents with an opportunity to transfer bad emotions and psychological catharsis81, which helps to improve interpersonal relationships, enhance self-confidence, and enhance their sense of life meaning and self-worth. Therefore, physical activity is known as the “green therapy” of bad mood82 and plays an important role in the treatment and relief of adolescent depression.

On the basis of verifying the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms, we also discussed the mediating role of psychological capital. Consistent with hypothesis 2, the data show that psychological capital is a complete mediator between physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Adolescents who regularly engage in physical activity and physical exercise are more likely to obtain higher psychological capital83, have more positive psychological reserves in the face of external pressure, and are less likely to produce depressive symptoms84. The findings once again confirm the effect of psychological capital on physical activity and depressive symptoms, further enriching existing research. According to the resource preservation theory, psychological capital, as an individual’s internal psychological resource, plays an intermediary role in mental health85, and individuals with long-term resource impairment will continue to increase their psychological pressure, inducing a series of psychological problems such as depression and anxiety44. Physical activity can hone adolescents’ strong will quality, improve individual mental health, enhance self-efficacy86, and improve psychological capital level87. At the same time, in the process of participating in physical activities, it is beneficial to improve the positive psychological quality of optimism. However, highly optimistic individuals are more inclined to maintain a positive coping attitude in the face of pressure and challenges in life and study88. Individuals with high hopes have firm beliefs and strong ability to face and solve problems89. At the same time, individuals with high self-efficacy and resilience usually possess certain self-control ability90, and can actively adjust their emotions to better adapt to the environment91. When adolescents have optimistic and confident life attitude, positive life hope and strong psychological resilience, they will deal with setbacks in life in a more positive way92, buffer or weaken the impact of external risk factors on psychological problems93, and stay away from depression and other negative emotions94. At the same time, adolescents often face the interference of external risk factors such as academic pressure, interpersonal communication, parent-child relationship and peer friendship54, which affect their psychological development and make them more prone to negative psychology such as inferiority, sensitivity, despair and pessimism about the future95,96,97,101,102,103,101. The ego depletion theory points out that positive psychological resources are limited, and long-term negative emotions, family environment and social environment risk factors will seriously depleting individuals’ positive psychological capital reserves, leading to a decline in psychological capital54. Therefore, it is extremely important to increase the amount of physical activity and exercise of adolescents and the reserve of psychological capital. According to the characteristics of the growth of psychological capital in various dimensions and the growth and development of adolescents, targeted exercise methods and means should be adopted to reduce the negative emotions of adolescents and the negative impact of family environment and social environment, increase the reserve of psychological capital, and maintain the healthy development of physical and mental health.

The results also confirm hypothesis 3 that gender regulates the latter half of the mediating process of physical activity → psychological capital → depressive symptoms. In contrast, girls’ psychological capital levels had a greater impact on their depressive symptoms. Social gender role theory points out that individual differences between men and women are caused by differences in gender roles, so boys have more aggressive and independent traits, while girls have more sensitive and warm-hearted traits, which will further affect the psychology and behavior of boys and girls102. At the same time, due to the influence of economic and educational level, girls have low self-esteem, self-confidence and other psychological qualities. Moreover, under the influence of traditional role expectations, more parents guide girls to develop in the direction of “quiet and obedient”103. Therefore, girls in adolescence are more likely to demand themselves in the role expectations of women under the influence of external environment, thus decreasing their enthusiasm to participate in physical activities and lower their physical activity level than boys104. Under the influence of multiple factors such as gender role and family concept, girls are more likely to have negative emotions such as depression and anxiety105,106, which lead to a series of psychological problems. Studies have shown that psychological capital has a stronger protective and buffering effect on girls, and when the level of psychological capital is low, the level of depressive symptoms is higher than that of boys. Therefore, when families, schools and society conduct psychological intervention on individuals, different measures should be taken according to the differences of individuals, especially girls with a low level of psychological capital. Compared with boys of the same age, they will be more sensitive and dangerous in this state. When they are at a low level of psychological capital for a long time, they will increase the risk of depression.

The strength of this study is the use of a unique sample of adolescents, with a sample of adolescents in economically disadvantaged rural areas, to explore in depth the relationship between psychological capital and gender and adolescent physical activity and depressive symptoms. Second, our study found that psychological capital can also alleviate and improve the symptoms of adolescent depression, effectively supplementing the prevention and treatment of adolescent depressive symptoms. Finally, this study found that gender has a moderating effect on psychological capital and depressive symptoms in adolescents, which has enriched the population research on the prevention and treatment of depressive symptoms.

While this study advances our understanding of the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms, there are still some limitations to consider. First of all, the survey on the teenagers in the three rural junior middle schools in western Hunan does not represent the overall situation of the teenagers in western Hunan, and the research results may be biased. Secondly, adolescent physical activity, depressive symptoms and psychological capital related indicators were all investigated by scale, and there may be recall bias among survey subjects. Finally, the cross-sectional survey data used in this study are not good at revealing causality, and more longitudinal studies are needed in the future to delve deeper into the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, physical activity negatively predicts depressive symptoms in adolescents, and psychological capital, as a positive internal resource, plays a mediating role between physical activity and depressive symptoms. Gender plays a significant moderating role in this relationship. Increasing daily physical activity and enhancing psychological capital can help prevent and reduce depressive symptoms, especially in girls.

Therefore, in order to effectively alleviate and prevent adolescent depression symptoms, the joint efforts of society, family and school are essential. The society should constantly improve and perfect the psychological aid system for adolescents, and provide timely and effective psychological counseling for adolescents; Schools should encourage young people to actively participate in sports activities, especially for girls, to gain more peer support and friendship in sports, so as to continuously strengthen the positive psychological capital reserves; In the family, parents should not only provide material support, but also understand and meet the psychological needs of teenagers. At the same time, we should learn to encourage and praise them, and help teenagers develop and deteriorate the psychological quality of self-confidence and optimism. Only the society, the school and the family work together, can better improve the overall level of adolescent mental health, to prevent the occurrence of psychological problems.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [our experimental team’s policy] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Weersing, V. R., Jeffreys, M., Do, M. T., Schwartz, K. T. & Bolano, C. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 46 (1), 11–43 (2017).

Xiaohan, J. I. A. N. G. & Zhi, Z. Analysis of the change trend of the burden of depression in children and adolescents in China . Chin. J. Prev. Med. 25(03), 379–384 (2019).

Ye, S. et al. Correlation between video and sleep duration and depressive symptoms in middle school students. Chin. Sch. Health 43(07), 1015–1018 (2022).

Tao, X. et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors of depressive symptoms in Chinese middle school students. Modern Prev. Med. 49(05), 814–818+844 (2022).

Chao, W. et al. Related factors of depressive symptoms in middle school students in Shandong Province. Chin. J. Ment. Health 37(04), 318–325 (2023).

Weiwei, Y. et al. Association of physical fitness, mobile phone dependence and depressive symptoms among freshmen in a medical college in Jiangsu Province. Chin. Sch. Health 45(05), 644–648 (2024).

Furong, L. et al. Meta-analysis of depressive symptoms in middle school students. Chin. J. Mental Health 34(02), 123–128 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Experiential avoidance, depression, and difficulty identifying emotions in social network site addiction among Chinese university students: a moderated mediation model. Behav. Inf. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2025.2455406 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Social network site addiction, sleep quality, depression and adolescent difficulty describing feelings: a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychol. 13(1), 57 (2025).

Pearce, M. et al. Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 79(6), 550–559 (2022).

Haitan, W. et al. Correlation between physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Chin. Sch. Health 44(05), 672–676+681 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. The relationship between physical activity and internet addiction among adolescents in western China: a chain mediating model of anxiety and inhibitory control. Psychol. Health Med. 29(9), 1602–1618 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Anxiety inhibitory control physical activity and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. BMC Pediatrics 24(1), 663. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-05139-6 (2024).

Xiao, T. et al. The relationship between physical activity and sleep disorders in adolescents: a chain-mediated model of anxiety and mobile phone dependence. BMC Psychol 12(1), 751. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02237-z (2024).

Peng, J. et al. Physical and emotional abuse with internet addiction and anxiety as a mediator and physical activity as a moderator. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 2305 (2025).

Yang, L. et al. The Chain Mediating Effect of Anxiety and Inhibitory Control and the Moderating Effect of Physical Activity Between Bullying Victimization and Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents. J. Genetic Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2025.2462595 (2025).

Shen, Q. et al. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 14(1), 24348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75919-8 (2024).

Xu, H., Luo, X., Shen, Y. & Jin, X. Emotional abuse and depressive symptoms among the adolescents: the mediation effect of social anxiety and the moderation effect of physical activity. Front. Public. Health 11, 1138813 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Relationship between bullying behaviors and physical activity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 78, 101976 (2024).

Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C. M. & Stubbs, B. Physical activity and depression: towards Understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 107, 525–539 (2019).

Ji Liu, W., Xiaozan, C. A. I. & Li Physical Exercise and Mental Health M216–218 (East China Normal University, 2006).

MEYER G W. Social information processing and social networks:a test of social influence MechanismsJ. Hum. Relat. 47 (9), 1013–1047 (1994).

Mengjie, Z., Yuanfu, D., Chen, W., Difa, X. & Changhao, J. Study on the effect of aerobic activity on depression in school-age children: an analysis of multiple mediating effects based on 5 dimensions of psychosocial function. Theory Practice Chin. Rehabil. 29(1), 12–19 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. The mediating role of inhibitory control and the moderating role of family support between anxiety and Internet addiction in Chinese adolescents. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 53, 165–170 (2024).

Xu, W. Physical exercise and depression in college students: the multiple mediating roles of mindfulness and social support. Social Scientist. 2, 148–155 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Anxiety mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents, and family support moderated the relationship. BMC Pediatr. 25(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-05348-z (2025).

Benaich, S. et al. Weight status, dietary habits, physical activity, screen time and sleep duration among university students. Nutr. Health 27, 69–78 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. The mediating effect of internet addiction and the moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Abstract. Sci Rep. 14(1), 9781. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60326-w (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Physical activity moderated the mediating effect of self-control between bullying victimization and mobile phone addiction among college students. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20855. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71797-2 (2024).

Zahl, T., Steinsbekk, S. & Wichstrøm, L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and symptoms of major depression in middle childhood. Pediatrics 139, e20161711 (2017).

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. et al. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep duration and their associations with depressive symptoms and other mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17(1), 72 (2020).

Herbert, C., Meixner, F., Wiebking, C. & Gilg, V. Regular physical activity, short-term exercise, mental health, and well-being among university students: the results of an online and a laboratory study. Front. Psychol. 11, 509 (2020).

Babaeer, L., Stylianou, M., Leveritt, M. & Gomersall, S. Physical activity, sedentary behavior and educational outcomes in university students: a systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Health. 70, 2184–2209 (2020).

Recchia, F. et al. Physical activity interventions to alleviate depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 177 (2), 132–140 (2023).

Hou, J. et al. Physical activity and risk of depression in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. J. Affect. Disord. 371, 279–288 (2025).

Schuch, F. B. et al. Physical activity and incident depression: A Meta-Analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Psychiatry. 175, 631–648 (2018).

Pearce, M. et al. Association between physical activity and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 79, 550–559 (2022).

Schuch, F. B. et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Psychiatry. 175 (7), 631–648 (2018).

Li, G., Xia, H., Teng, G. & Chen, A. The neural correlates of physical exercise-induced general cognitive gains: A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 169, 106008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106008 (2025).

Shen, L., Gu, X., Zhang, T. & Lee, J. Adolescents’ physical activity and depressive symptoms: A psychosocial mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19(3), 1276 (2022).

Li, J. Y. et al. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in China: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 7459–7470 (2019).

Yongjin, X. et al. College students’ level of physical activity and depressive symptoms associated cohort study. J. Sch. Health China. 03, 406–410 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. The relationship between cyberbullying and depression in college students: the moderating role of psychological capital and peer support. J. Psychol. Sci. 47 (04), 981–989 (2024).

Changlong, S. et al. College students’ subthreshold depression and double attribution: the relationship between psychological capital intermediary function. Chin. J. Health psychol. 31(8), 1212–1216 (2023).

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B. & Norman, S. M. Positive psychological capital:measurement and relationship with performance and. Satisfaction Personnel Psychol. 60 (3), 541–572 (2007).

Fan XingHua, Y. et al. The relationship between life stress, loneliness and happiness of left-behind children: the mediating and moderating role of psychological capital J. Psychol. Sci. 40 (2), 388–394 (2017).

Yuanhua, L., Xianghai, H. & Hui, C. Relationship between Physical exercise and psychological capital of Zhuang left-behind primary and middle School students in poor areas of Guangxi. Modern Prev. Med. 47(21), 3915–3918 (2020).

Yaqi, D. et al. The effect of physical exercise on school bullying in junior high school students: the chain mediating effect of psychological capital and self-control. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 31(5), 733–739 (2023).

Menglong, L. et al. The effect of physical activity on social anxiety of rural left-behind children: the mediating role of psychological capital. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 28(6), 1297–1300+ 1296 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. The relationship between physical activity and college students’ mobile phone addiction: the Chain-Based mediating role of psychological capital and social adaptation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (15), 9286 (2022).

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., Smith, R. M. & Palmer, N. F. Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 15 (1), 17–28 (2010).

He, S. et al. The Influence of Social support on career decision making of young football players: the chain mediation effect of core self-evaluation and psychological capital. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 31(8), 1234–1238 (2023).

Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology.the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56 (3), 218–226 (2001).

Wenyan, M. et al. The Relationship between family cumulative risk factors and sense of life Meaning of rural students: the mediating role of psychological capital. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 30(03), 431–436 (2022).

Hongli, M. et al. The influence of psychological capital of adolescent depression. Guangdong Med. 4(01), 27–29 (2015).

Jiajia, H. et al. Association between physical activity and physical fitness index in Chinese children and adolescents. Chin. Sch. Health. 42(12), 1879–1882+1887 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Analysis of physical exercise behavior and related factors of high school students in Taizhou [J]. Chin. J. School Health. 45 (07), 965–968 (2019).

Zook, K. R., Saksvig, B. I., Wu, T. T. & Young, D. R. Physical activity trajectories and multilevel factors among adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. Health. 54 (1), 74–80 (2014).

Huang Yilin, M. et al. Effect of health education and exercise intervention on BMI of middle school students in urban areas J. Chin. Public. Health. 34 (1), 33–37 (2018).

Gao, T. et al. Parental psychological aggression and phubbing in adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Psychiatry Investig. 19 (12), 1012–1020 (2022).

Guo Jiacheng, D. O. N. G. & Rochun, X. The relationship between social presence and internet hyperactivity in college students: the parallel mediation of dual self-awareness and the moderating role of gender [J]. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 40 (02), 176–186 (2019).

Yuan, Y., Zhou-Jian, L. I. A. N. G. & Li, Z. H. A. N. G. Structural school climate and depression in middle school students: the mediating role of social support and the moderating role of gender [J]. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 39 (06), 869–876 (2019).

Dong, H. et al. China child and adolescent cardiovascular health (CCACH) collaboration members. Reference centiles for evaluating total body fat development and fat distribution by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry among children and adolescents aged 3–18 years. Clin. Nutr. 40 (3), 1289–1295 (2021).

Hai, Z. et al. Current situation of depression and anxiety among middle school students in Beijing and its relationship with bullying and violence. Chin. Sch. Health 45(07), 1017–1020+1025 (2024).

Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S. & Abramson, L. Y. Gender differences in depression in representative National samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol. Bull. 143 (8), 783–822 (2017).

Hongli, M. A. et al. Li Jie, Li Hongzheng. The influence of psychological capital on adolescent depression. J. Guangdong Med. 36 (01), 27–29 (2015).

Menglong, L. et al. The effect of physical activity on social anxiety of rural left-behind children: the mediating role of psychological capital. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 28(6), 1297–1300+ 1296 (2020).

Finch, J. et al. Searching for the hero in Youth:Does Psychological Capital (PsyCap) Predict Mental Health Symptoms and Subjective Wellbeing in Australian school-aged Children and adolescents?J511025–1036 (Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 2020). 6.

Jianbo, Q. & Aihua, Y. Intervention effect of moderate intensity physical exercise on inferiority and psychological capital of college students. Chin. Sch. Health 40(05), 756–758 (2019).

Liang, D. Q. Stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Chin. Ment. Health J. 8, 2 (1994).

Zhiyan, C., Xiaodong, Y. & Xinying, L. The study of depression scale in Chinese adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 17(04), 443–445+448 (2009).

Fang Biji. A Study on the structure, characteristics, Related Factors and Group Intervention of College students’ Psychological capital D. Fuzhou: College of Education, Fujian Normal University. :50–63. (2012).

Kim, H. Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dentist Endodont. 38 (1), 52–54 (2013).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies journal Article; review. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903 (2003).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation,moderation,and Conditional Process analysis:A regression-based Approach (The Guilford Press, 2013).

Velazquez, B. et al. Physical activity and depressive symptoms among adolescents in a school-based sample. Braz J. Psychiatry. 44 (3), 313–316 (2022).

Ma, L., Hagquist, C. & Kleppang, A. L. Leisure time physical activity and depressive symptoms among adolescents in Sweden. BMC Public. Health. 20 (1), 997 (2020).

Zhao, J. L. et al. Exercise, brain plasticity, and depression. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 26 (9), 885–895 (2020).

Rothon, C. et al. Physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents: a prospective study. BMC Med. 8, 32 (2010).

Camero, M, Hobbs, C, Stringer, M, Branscum, P, & Taylor, E L. A review of physical activity interventions on determinants of mental health in children and adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 14(4), 196–206(2012).

Hong Xin, Liang Yaqiong, Wang Zhiyong, et al. Physical activity and its correlation with depressive symptoms in Nanjing middle school students .J. Chinese School Health.28(12):1059-1061(2007) .

Wang Lin, J. & Longjun, H. International hotspot and evolution of sports intervention in promoting adolescent health. J. Chin. School Health. 40 (5), 669–675 (2019).

Chongyong, S. & Zhongjun, Y. The relationship between physical exercise and psychological capital of middle school students J. Chin. School Health. 36 (11), 1672–1675 (2015).

Bakker, D. J., Lyons, S. T. & Conlon, P. D. An exploration of the relationship between psychological capital and depression among first-year doct or of veterinary medicine students. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 44, 50–62 (2017).

Fu Liang. A Study on the Relationship between Attribution Style, Psychological Capital and Mental Health of Middle School Students who Have Been Impoverished D (Kashgar University, 2022).

Sheng Jianguo, G., Shouqing, T. & Guangxu The effect of physical exercise on the mental health of middle school students: the mediating role of self-efficacy J. Chin. Sports Sci. Technol. 52 (5), 98–103 (2016).

Wang, Y. Effect of secondary physical exercise on physical self-esteem and psychological capital of college students J. Chin. School Health. 37 (11), 1661–1663 (2016).

Gao, Y., Lu, C., Zhang, X., Han, B. & Hu, H. Physical activity and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior in Chinese adolescents: the chain mediating role of psychological capital and relative deprivation. Front. Psychiatry. 15, 1509967 (2024).

Chang, E. C. et al. Hope as a process in Understanding positive mood and suicide protection. Crisis 43, 90–97 (2022).

Wang, A. et al. The chain mediating effect of self-respect and self-control on the relationship between parent-child relationship and mobile phone dependence among middle school students. Sci. Rep. 14, 30224. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80866-5 (2024).

Yaqi, D. et al. The effect of physical exercise on school bullying in junior high school students: the chain mediating effect of psychological capital and self-control. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 31(5), 733–739 (2023).

Ho, H. C. Y., Chui, O. S. & Chan, Y. C. When Pandemic Interferes with Work: Psychological Capital and Mental Health of Social Workers during COVID-19. Soc. Work. 67(4), 311–320 (2022).

Qian, L. & Guohua, Z. The dual mechanism of psychological capital on the relationship between family cumulative risk and mental health of college students. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 30(9), 1365–1370 (2022).

Sun, L. et al. Relationship between psychological capital and depression in Chinese physicians: The mediating role of organizational commitment and coping style. Front. Psychol. 13, 904447 (2022).

Xinqiang, W. et al. Comparison of mental health, abuse experience and relationship between left-behind and non-left-behind children in rural areas: Analysis and suggestions based on two-dimensional four-image mental health structure. Chin. Special Edu. 01, 58–64 (2018).

Li, H., Jiwei, Y. & Qinqin, Z. Effects of life events on mental health of rural left-behind children: the mediating role of peer attachment, psychological resilience and the moderating role of security. Chin. Special Edu. 07, 55–62 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. The relationship between early adolescent bullying victimization and suicidal ideation: the longitudinal mediating role of self-efficacy. BMC Public Health 25(1), 1000 (2025).

Yang, L. et al. Child psychological maltreatment, depression, psychological inflexibility and difficulty in identifying feelings, a moderated mediation model. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 8478 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. The relationship between childhood psychological abuse and depression in college students: internet addiction as mediator, different dimensions of alexithymia as moderator. BMC Public Health 24, 2744. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20232-2 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. The relationship between childhood psychological abuse and depression in college students: a moderated mediation model. Abstract. BMC Psychiatry 24, 410. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05809-w (2024).

Yang, L. et al. The chain mediating effect of anxiety and inhibitory control between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents Sci. Rep. 14(1), 23350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74132-x (2024).

Ngo, H. Y. et al. Linking gender role orientation to subjective career success: the mediating role of psychological capital. J. Career Assess. 22(2), 290–303 (2014).

Dazhen, X., Riyi, Z. & Yu, K. A cross-cultural study of implicit and explicit gender effects in gender stereotypes. Psychol. Sci. 31(5), 1226–1229 (2008).

Molina, A. J. et al. Unhealthy habits and practice of physical activity in Spanish college students: the role of gender, academic profile and living situation. Adicciones. 24(4), 319–327 (2012).

Ajmal, M. et al. Exploration of anxiety factors among students of Distance Learning: a case study of Allama Iqbal Open University. B. Educ. Res. 41(2), 67–78 (2019).

Mirza, A. A. Depression and anxiety among medical students: a brief overview. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 12, 393–398 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the school staff for their valuable support. We would also like to express our heartfelt thanks to all the students who participated in this project.

Funding

Jishou University graduate level research project (Jdy23144).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiangyu Luo123456, Hanqi Liu135, Zhaoyang Sun135, Qin Wei125, Jianhua Zhang256, Tiancheng Zhang256, Yang Liu1256.1 Conceptualization; 2 Methodology; 3 Data curation; 4 Writing - Original Draft; 5 Writing - Review & Editing; 6 Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Biomedicine Ethics Committee of Jishou University before the initiation of the project (Grant number: JSDX−2024−0086). Informed consent was obtained from the participants and their guardians before the start of the program. We confirm that all the experiment is in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations such as the declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, X., Liu, H., Sun, Z. et al. Gender mediates the mediating effect of psychological capital between physical activity and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 10868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95186-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95186-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The impact of childhood emotional maltreatment on adolescent insomnia: a chained mediation model

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

The relationship between physical activity and social network site addiction among adolescents: the chain mediating role of anxiety and ego-depletion

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

Mobile phone addiction was the mediator and physical activity was the moderator between bullying victimization and sleep quality

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

The relationship between family support and Internet addiction among adolescents in Western China: the chain mediating effect of physical exercise and depression

BMC Pediatrics (2025)

-

Chain-mediation effect of cognitive flexibility and depression on the relationship between physical activity and insomnia in adolescents

BMC Psychology (2025)