Abstract

The goal of this study was to explore the impact of psychological resilience on the QOL of cancer patients and the multiple mediating roles of stigma and self-perceived burden. This study utilized a cross-sectional design. The study population consisted of 364 cancer patients selected by convenience sampling method between November 2022 and May 2023 in two tertiary hospitals in Jinzhou City, Liaoning Province. All participants volunteered to participate in the study and signed an informed consent form. Data were collected using questionnaires. The questionnaires included the General Information Questionnaire, the Psychological Resilience Scale, the Stigma Scale, the Self-Perceived Burden Scale, and the Quality of Life Questionnaire. SPSS 25.0 and PROCESS 3.5 macros were employed for description statistics and related analyses of the data, as well as multiple mediation effect tests. Psychological resilience directly affects QOL (β = 0.929, 95% CI 0.729–1.130) and indirectly through three mediating pathways: stigma (β = 0.275, 95% CI 0.154–0.398, 19.76% of total effect), self-perceived burden (β = 0.115, 95% CI 0.046–0.205, 8.26% of total effect), and both stigma and self-perceived burden (β = 0.073, 95% CI 0.029–0.132, 5.24% of total effect), accounting for 33.26% of the overall mediated effect. Stigma and self-perceived burden act as mediators in influencing psychological resilience and QOL of cancer patients. Enhancing psychological resilience and reducing stigma and self-perceived burden is crucial for improving their QOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following advances in medical technology, the survivorship rate of cancer patients has improved, but the issue of QOL during therapy and recovery has attracted widespread attention1,2. QOL is defined as an individual’s experience of his or her state of being in terms of the goals, hopes, standards, and concerns that he or she pursues in the context of different value systems and cultures3. The QOL of cancer patients is not only an essential indicator of the effectiveness of clinical treatment but also predicts and judges the long-term survival of patients4. Therefore, it is of vital importance to assess and intervene in the QOL of cancer patients.

The QOL of cancer patients is influenced by several factors, among which psychological resilience is especially vital5. Psychological resilience is the mental ability of an individual to adapt, regulate, and restore in the face of adverse situations, stresses, and challenges6. Extensive research has demonstrated that psychological resilience is an important psychological immune system for cancer patients, which can effectively resist negative moods such as anxiety and depression, and maintain patients’ mental health and QOL7,8. For the relationship between psychological resilience and QOL, Boškailo et al. revealed that psychological resilience was positively correlated with QOL9. Yang et al. indicated that psychological resilience was a major influence on QOL10. Liang et al.'s study pointed out that higher psychological resilience helps to improve the QOL, coping ability, and psychological health of cancer patients11. Therefore, it is essential to explore psychological resilience to improve the QOL of cancer patients.

Current research suggests that stigma is prevalent among cancer patients12. Stigma is the internal feeling that people feel ashamed because they have a certain disease13. Stigma is not only harmful to the psychological health of cancer patients, but more seriously, it affects the patients’ behavior of actively seeking medical treatment, delays the best time for treatment, and is ultimately linked to a decrease in their QOL14. Moreover, the Snyder et al. study pointed out that psychological resilience, an effective protective factor, was significantly associated with cancer-induced stigma15. Cho et al. indicated that the higher the level of psychological resilience in cancer patients, the lower the likelihood that they would develop stigma16. These findings suggest strong links between stigma and psychological resilience with QOL in cancer patients. However, there is a relative lack of investigation into whether stigma plays a mediating role between psychological resilience and QOL.

In cancer patients, stigma and self-perceived burden are two notable psychological distress factors17,18. Huge medical expenses, changes in family roles, the pain of leaving loved ones soon, and worries about the disease all give patients pressure that they cannot bear and discharge, causing them to suffer both physical and psychological torture, which leads to guilt, a sense of burden, and so on, i.e., self-perceived burden19. Self-perceived burdens are empathic concerns that individuals have as a result of their illness and caregiving needs affecting others, including the emergence of negative emotions such as guilt, suffering, and a weakened self-awareness20. Kim et al.'s study showed that stigma is intimately linked to self-perceived burden in cancer patients21. Yeung et al.'s study demonstrated that stigma can limit cancer patients’ ability to seek assistance from their families and society, aggravate their self-perceived burden, and in turn affect their QOL22,23.

Additionally, as positive psychology research has deepened, scholars inquired into the relationship between psychological resilience and self-perceived burden. Zhang et al.'s study on colorectal cancer patients revealed that patients with higher levels of psychological resilience had relatively lower levels of self-perceived burden24. Another study on primary liver cancer patients came to a similar conclusion that psychological resilience can be effective in reducing stress and self-perceived burden25. Furthermore, Ting et al. found that cancer patients with higher self-perceived burden typically faced more severe financial difficulties, had more depressive symptoms, and had lower quality of life26. Xiaodan et al. showed that cancer patients with higher self-perceived burdens tended to suppress their emotions and minimize the burden of care for family members, and thus the QOL suffered27,28,29,30. Given the above analysis, self-perceived burden may mediate the relationship between psychological resilience and QOL.

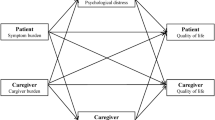

Based on these analyses, stigma and self-perceived burden may serve as chain mediators in psychological resilience and QOL for cancer patients. Therefore, we proposed three hypotheses to construct the hypothesized model of the study (Fig. 1). To begin, hypothesize that psychological resilience can influence QOL via stigma (H1). Second, the hypothesis is that self-perceived burden mediates the relationship between psychological resilience and QOL (H2). Third, the hypothesis is that stigma and self-perceived burden may serve as chain mediators between psychological resilience and QOL (H3).

Methods

Design and sample

This study utilized a cross-sectional design. By random sampling method from November 2022 to May 2023, questionnaires were administered to cancer patients in two tertiary hospitals in Jinzhou City, Liaoning Province. For calculating the sample size, we used an application developed by Schoemann in the statistical computing language R, which is based on the Monte Carlo confidence interval power analysis method31,32. The required parameters were entered sequentially and several runs were performed to ensure the stability of the results. When the conventional power level of 0.80 was chosen, the minimum required sample size was 133. To reduce the probability of error, we increased the sample size to 400 (Power = 1.0). After excluding missed and invalid questionnaires, we finally recovered 364 valid questionnaires (Power = 0.99), which is an effective recovery rate of 91%. Questionnaires were given to a total of 364 patients in this study to ensure the precision of the experiment. Criteria for inclusion (1) Clinically and pathologically diagnosed cancer patients; (2) Well-informed consent and willingness to fulfill the study; (3) Sober-minded and with good communication skills. (4) Being ≥ 18 years of age. Elimination criteria: (1) Critically ill and unable to cooperate with the study; (2) those with an expected survival time of less than six months; (3) those with cognitive disabilities or psychiatric disorders; (4) those who had received psychological interventions in the past year, which could have affected the findings; and (5) People who are unknown to their disease.

Before starting the survey, investigators received standardized training to establish scoring criteria and communication skills. The researchers then administered the questionnaire to cancer patients at two Grade 3A hospitals. They handed out paper questionnaires to qualified cancer patients one by one and explained in detail the context, objective, and meaning of the study to the patients and their relatives and provided instructions for completing the survey before handing out the questionnaires. The patients completed the questionnaires independently after obtaining their consent. In patients with low levels of literacy or writing difficulties, the researcher spoke with them and assisted them in completing the questionnaires. Upon completion of the questionnaire, the researcher retrieved the questionnaire on the spot, checked the quality of the questionnaire to ensure its completeness and accuracy, and confirmed the necessary changes with the patients. Patients on average completed the questionnaire within 10–15 min. A total of 400 cancer patients were approached for this study, of which 36 patients were excluded because they refused to participate or did not meet the inclusion criteria. In the end, a total of 364 patients met the inclusion criteria and were successfully included in the study. Therefore, a total of 364 valid questionnaires were collected. All methods followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

Instruments

General demographic characteristics questionnaire

Demographic characteristics included Age, Gender, Marital status, Medical condition, Monthly personal income, Smoking status, Education Level, Drinking status, Tumor Staging, and Lymph metastasis.

Psychological Resilience Scale

The scale was originally developed by Campbell-Sills et al. in 2007 based on a careful selection of 10 items from the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale to accurately assess an individual’s level of psychological resilience in response to stressful situations33. Subsequently, in 2010, Wang Li et al. translated it into a Chinese version, and the scale is now widely used among the Chinese adult population and cancer patients34. It is used to measure an individual’s level of psychological resilience in response to stress and is widely applicable to Chinese adults and cancer patients. The scale consists of 10 items with a single-dimensional structure. Likert 5-point scales were used, ranging from 0 = “never” to 4 = “always”, and the scores of the 10 items were added together to give a total score, which ranges from 0 to 40, with greater scores indicating higher levels of psychological resilience. In this study, the scale had a high reliability and validity with a Cronbach coefficient of 0.912 and a KMO value of 0.932.

Stigma Scale

The Stigma Scale was originally developed by Wright and Fife in 2000 to assess the level of stigma in patients with cancer and AIDS35 and was translated and revised into the Chinese version of the Social Impact Scale (SIS) by Pan Aiwen et al. in 2007, which is now widely used to measure stigma in cancer patients36. The scale contains a total of 24 entries divided into 4 dimensions, specifically intrinsic stigma (entries 11–14, 19), economic discrimination (entries 1, 2, 4), social exclusion (entries 8–10, 3, 6, 5, 15, 22, 21), and social isolation (entries 16, 18, 7, 17, 23, 20, 24). The sum of scores for the 4 dimensions is the total score of the scale. Overall scores ranged from 24 to 96, with 24–47 being a light level, 48–71 being a medium level, and 72–96 being a serious level. The greater the score, the greater the individual’s perceived stigma. In this study, the scale had a Cronbach’s coefficient of 0.894 and a KMO value of 0.883, indicating that the scale had good reliability and validity.

Self-perceived Burden Scale

This scale was created by Cousineau et al. in 200337 to assess the status of self-perceived burden in patients with chronic diseases. Wu Yanyan et al. formed a Chinese version of this scale through rigorous translation and back-translation procedures in 2010 and validated its measurement and validation in a population of cancer patients38. It includes a total of 10 entries, which are categorized into three dimensions: physical burden (items 1 and 10), emotional burden (items 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9) and financial burden (items 3 and 8). Likert 5-point scale with scores from 1 to 5 on a scale from “never” to “always”, ranging from 10 to 50 points. Higher total scores indicate greater self-perceived burden. The self-perceived burden was categorized into four levels according to the scores: < 20 points for no significant burden, 20–29 as a light burden, 30–39 as a medium burden, and > 40 as a serious burden. In this study, the Cronbach’s coefficient of this scale was 0.858 and KMO was 0.855 with good reliability and validity.

Quality of Life Scale

This scale was developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer to evaluate the QOL of survival of cancer patients39. Wan Chonghua et al. demonstrated that the Chinese version of the scale has good reliability and validity, and is currently a universal quality-of-life scale for cancer patients40. The scale consists of 30 entries and 15 domains. The quality of survival is measured in five domains of functioning (somatic functioning, role functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, and social functioning), three domains of symptoms (fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting), one level of general health, and six individual items (sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, diarrhea, constipation, respiratory difficulties, and financial difficulties). The scoring system is as follows: for entries 1–28, scores are calculated based on 1, 2, 3, and 4; for entry 29 and entry 30, scores are calculated based on 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. Higher scores for functional domains and general health status indicate better functional status and QOL, and for symptom domains higher scores indicate more symptoms or problems and poorer QOL. In this study, only the subscales of functional domains and general health status of the QOL Scale were used. In this study, the scale had a Cronbach’s coefficient as high as 0.861 and a KMO value of 0.904, both showing good reliability and validity.

Statistical analysis

We used IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 and the PROCESS 3.5 macros for data analysis. First, a Harman one-way test was utilized to evaluate potential common method bias. Next, describe statistics of the data were presented using frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The effects of different demographic characteristics on QOL scores were compared by independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA. Pearson correlation analysis was utilized to describe the correlation between the variables. Finally, model 6 in PROCESS 3.5 was used to test the mediating effect. The reasons for choosing Model 6 are as follows: (1) Testing multiple mediating variables at the same time: we hypothesized that stigma and self-feeling burden play a mediating role between psychological resilience and quality of life, respectively. The PROCESS Model 6, which can test both mediating variables at the same time, is suitable for our research design and is more in line with the research hypotheses than a single mediating model. (2) Theoretical framework support: according to the theoretical framework, psychological resilience affects the quality of life through effective mechanisms such as stigma and self-perceived burden, and Model 6 can effectively test these multilevel mediating pathways. (3) More precise indirect effect estimates: by considering both mediating variables, Model 6 provides more precise indirect effect estimates, which helps to better understand how psychological resilience affects quality of life through these two mediating variables, and enhances the validity and reliability of the research results. Therefore, the selection of PROCESS model 6 can accurately test our proposed hypotheses and provide strong statistical support for exploring the effects of psychological resilience on quality of life. In our study, the bootstrap method was utilized to replicate the sampling 5000 times, and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. If the 95% CI did not contain 0, it indicated a significant mediation effect. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Common method bias

Given that self-report methods may introduce common method bias, we conducted a Harman one-way test to assess this potential issue. Without rotation, we identified 16 common factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1. The first factor accounted for 24.81% of the variance, well below the 40% threshold. It means that there is no significant common method bias in this research.

Characteristic of participants

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study participants and the univariate analysis of the QOL of the study participants with different characteristics. Out of 364 cancer patients, 191 (52.5%) were male and 173 (47.5%) were female. The age range of the patients was 28–92 years with a mean age of 60.19 ± 10.72 years. Most of the study subjects were married (93.4%) and about 95.1% of the patients had health insurance. QOL varied by education level, individual monthly income, and tumor stage, and these variables were retained as potential confounders in the mediation analysis. More details are provided in Table 1.

Correlations between overall variables

Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed that psychological resilience had a negative correlation with both stigma and self-perceived burden and a positive correlation with QOL (p < 0.01). Stigma was positively correlated with self-perceived burden and negatively correlated with QOL (p < 0.01). A self-perceived burden was negatively correlated with QOL (p < 0.01). See Table 2.

Mediation analysis

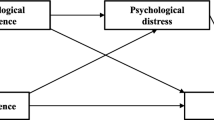

After controlling for the effects of education, individual monthly income, and tumor staging, we used Model 6 from Hayes’ Process macros to investigate the mediating roles of stigma and self-perceived burden in the relationship between psychological resilience and QOL (See Table 3 and Fig. 2). Results showed that psychological resilience was a significant positive prediction of QOL (B = 0.929, p < 0.001), whereas it was a significant negative prediction of both stigma (B = -0.734, p < 0.001) and self-perceived burden (B = -0.235, p < 0.001). Additionally, stigma was a significant positive predictor of self-perceived burden (B = 0.204, p < 0.001) and a negative predictor of QOL (B = -0.374, p < 0.001). Self-perceived burden significantly negatively predicted QOL (B = -0.488, p < 0.001).

Bootstrap analysis was used for the mediation effect test and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The results of the mediation effect test for the stigma showed that the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval were not zero, indicating that the stigma mediated the effect of psychological resilience on QOL, with a mediation effect of 0.275, accounting for 19.76% of the total effect. The results of the mediation effect test for the self-perceived burden showed that the self-perceived burden mediated the effect of psychological resilience on QOL, with a mediation effect of 0.115, accounting for 8.26%. The analysis of the chain mediation effect between stigma and self-perceived burden demonstrated a significant result, with a mediation effect of 0.073, contributing to 5.24% of the total effect (refer to Table 4).

Discussion

Our study explored the relationship between psychological resilience and QOL in cancer patients and analyzed for the first time the role of stigma and self-perceived burden in this process. The findings show that psychological resilience is significantly and positively correlated with QOL in all cancer patients and that this correlation is partially mediated by stigma and self-perceived burden.

Our findings show that patients with a monthly income of more than 5,000 RMB have a higher quality of life compared to cancer patients with other monthly income levels. This may be because higher income enables these patients to afford better healthcare services and health management so that they can receive timely and quality treatment, checkups, and rehabilitation care. For example, they can choose more advanced treatments, undergo regular checkups, purchase over-the-counter medications, or participate in health improvement programs (e.g., nutritional support, psychological counseling, etc.)41. On the other hand, cancer patients with lower literacy levels (e.g., elementary school and below) have lower quality of life. This may be because patients with low literacy usually lack adequate health knowledge and self-management skills, leading to difficulties in disease prevention, treatment, and self-care. For example, they may not be able to fully understand the treatment plan or know how to properly implement the doctor’s advice to effectively manage their health and cope with their illness, thus leading to a relatively lower quality of life42. In addition, Stage IV cancer patients have a lower quality of life mainly because the cancer cells have spread to other organs or tissues (metastasis) at this stage, which may cause impaired functioning of multiple organs or increased pain, thus significantly decreasing the patient’s physical functioning and quality of life43. At the same time, Stage IV cancer usually means that the disease is irreversible, and patients may lose hope for the future, believing that they cannot control their disease or improve their health. Such negative perceptions and attitudes can have a serious impact on their emotional state, which in turn adversely affects their quality of life44.

According to the current study, we found that the psychological resilience of cancer patients has a significant direct impact on their QOL, which is consistent with previous studies and in line with the theoretical perspectives of the psychological resilience framework.45,46. This may be because cancer patients with low psychological resilience usually lack effective coping strategies and support systems when dealing with the stress and challenges of the disease, and therefore often feel isolated and helpless, linked to a relatively low QOL47. On the contrary, cancer patients with higher psychological resilience are usually able to take effective coping measures (e.g., actively seeking social support, learning relaxation techniques, etc.), which help them maintain confidence and courage in overcoming difficulties, and motivate them to better follow medical advice, acquire self-health management skills, actively cope with difficulties, perform self-care activities, regulate their emotions, and socialize on their own, etc., thus linked to a relatively high QOL48. It has been shown that there is a certain interaction between psychological resilience and coping49. Effective coping strategies can enhance an individual’s adaptive capacity, thereby increasing psychological resilience, while stronger psychological resilience enables individuals to choose more positive and effective coping styles in the face of stress, thereby improving their quality of life50,51. Therefore, future research and clinical practice should focus on developing psychological resilience and encouraging positive coping strategies in cancer patients to improve their overall quality of life.

The results of this study show that psychological resilience can influence the QOL of cancer patients through the mediating factor of stigma. Cancer diagnosis brings fear, the unfamiliarity of the medical environment, and the unpredictability of treatment outcomes may significantly increase psychological stress and weaken psychological resilience in cancer patients52. Cancer patients with low psychological resilience are more likely to internalize negative societal attitudes toward the disease15,53. They may perceive their cancer as a failure or defect in themselves, linked to a strong stigma16,54. And the stigma may have a significant impact on the quality of life of cancer patients55. Specifically, on one hand, the stigma may cause patients to avoid participating in important social activities or duties due to the fear of discrimination and prejudice from others, which may associated with the absence of social roles and degradation of functioning, thus affecting their QOL56. On the Other hand, stigma may cause cancer patients to feel ashamed of their condition and unwilling to actively seek and accept treatment, which may associated with further deterioration of their physical condition and affect their QOL57. Therefore, we should pay attention to the stigma of cancer patients and take timely and targeted measures to ameliorate the problem to improve their QOL.

Our study found that psychological resilience, mediated through self-perceived burden, influences the QOL of cancer patients. Side effects from cancer treatment, such as nausea, fatigue, and hair loss, not only directly affect a patient’s physical health, but may also negatively impact his or her emotional and psychological resilience58. Cancer patients with low psychological resilience tend to focus excessively on their shortcomings and mistakes while ignoring their strengths and achievements. This self-perception bias will increase the self-perceived burden of cancer patients24. Self-perceived burden not only affects the patient’s ability to function at work, socially, and in family life but may also cause the patient to lose confidence in adhering to a healthy lifestyle, such as diet and exercise, which can linked to a decrease in his or her QOL27,28. Therefore, in addition to focusing on the psychological resilience of cancer patients, healthcare professionals should focus on patients with self-perceived burden to implement personalized interventions as early as possible to improve their QOL.

In addition, our study found that psychological resilience influences the quality of life of cancer patients through a partial chain mediation of stigma-self-perceived burden. This result can be better explained by the Cognitive Activation Theory of Stress59. In this theory, psychological resilience is an individual’s ability to cope with stress and challenges. Stigma is the cognitive response to stress activation. The self-perceived burden is the adverse emotions brought about by this cognitive response. While high or low quality of life in cancer patients is seen as a result of individual adaptation to stressful situations. In specific, stressful events such as cancer diagnosis, treatment, financial pressures, role transitions, and the doctor-patient relationship and healthcare environment may adversely affect a patient’s psychological resilience60. Cancer patients with low levels of psychological resilience are prone to lose confidence in their health status and future, associated with low self-esteem and stigma61. The stigma may cause patients to be excessively self-blaming and self-critical, believing that they do not deserve to be cared for and loved, thus triggering or exacerbating their self-perceived burden62,63. The self-perceived burden can worsen the patient’s mental state, and anxiety and depression gradually accumulate, forming a vicious cycle that ultimately reduces the overall QOL of cancer patients30. Thus, the results of this study support the Cognitive Activation Theory of Stress and emphasize the importance of psychological resilience, stigma, and self-perceived burden for the QOL of cancer patients. Overall, these findings remind us to focus on the development of psychological resilience, emphasize the improvement of stigma, and intervene in a timely manner with self-perceived burden when managing cancer patients in order to improve the overall QOL of cancer patients.

In summary, this study aims to comprehensively explore the potential factors of the relationship between psychological resilience and quality of life in cancer patients and to provide useful information for early detection and prevention of quality of life decline, which has both theoretical and practical significance. Based on the above findings, we suggest that healthcare professionals should pay attention not only to patients’ psychological resilience but also to their stigma and self-perceived burden when improving the quality of life of cancer patients. To this end, the following intervention strategies are worthy of further implementation: (1) Psychological resilience training: healthcare professionals can provide cancer patients with intervention programs that target psychological resilience. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help patients identify and change negative thought patterns, thereby improving their ability to cope with stress. In addition, Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBI) can help patients enhance their ability to regulate their emotions, reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms, and improve psychological resilience64. (2) Reduction of stigma: To help patients effectively deal with stigma, healthcare professionals can carry out psychological support services for stigma reduction. For example, group psychological support meetings are regularly organized, and patients are invited to share their personal experiences and provide emotional support to help them recognize the sense of shame and get relief from social support. In addition, patients can further deepen their understanding of the source of the stigma and explore effective ways to cope with it through individual exchanges with professional counselors65. (3) Enhancement of social support: The social support network of cancer patients is crucial to their quality of life. Healthcare professionals should help patients establish a positive support system, including family, friends, and community resources. For example, patient support groups can be organized to promote interaction and support among patients. By enhancing patients’ social support, we can help them gain more emotional support during the treatment process, reduce their self-perceived burden, and improve their quality of life66. Through these specific interventions, we are expected to improve the psychological resilience of cancer patients, reduce the stigma, lessen the self-perceived burden, and ultimately improve their quality of life. These interventions will not only contribute to the emotional well-being of patients but will also provide healthcare professionals with practical intervention frameworks to guide clinical practice.

This study has several limitations. First, we used a cross-sectional design, which prevented us from definitively determining the causal relationships between psychological resilience, stigma, self-perceived burden, and QOL. To explore the causal relationships of these variables in depth, future studies should consider adopting a more rigorous longitudinal study design. Second, although this study controlled for education level, monthly personal income, and tumor staging, other variables such as age and gender were not included as covariates. Preliminary univariate analyses showed no significant associations between age, gender, etc., and QOL in our sample, suggesting that these variables may not have a significant impact on the study relationship in this particular population. However, this finding may be limited by sample size and study design. To address these limitations, future studies should consider including age, gender, and other potentially confounding variables in their analyses. This approach could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence QOL in cancer patients. Third, our study results relied primarily on patient self-reports rather than more objective clinical interviews, which may have led to subjectivity bias and response bias in the data. To further enhance the objectivity and accuracy of the study, future studies could combine clinical interviews and objective physiologic indicators for assessment. Finally, the sample of this study mainly originated from Liaoning Province, China, which may limit the generalizability and replication of the study results to represent cancer patients from other regions of China or different cultural backgrounds. To ensure that the findings are more generalizable, future studies should consider expanding the sample size to cover a broader group of Chinese cancer patients and conducting further validation studies in different geographical and cultural settings to more fully explore and understand the complex relationship between psychological resilience, stigma, self-perceived burden, and QOL.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating role of stigma and self-perceived burden between psychological resilience and QOL in cancer patients. The results of the study showed that psychological resilience had a significant impact on QOL directly, part of which was realized through the mediating factors of stigma and self-perceived burden, with an overall mediating effect of 33.26%. Considering the prevalence of low QOL among cancer patients, it is particularly important to take multifaceted measures to improve their QOL. Stigma and self-perceived burden play a mediating role between psychological resilience and QOL, therefore, healthcare professionals and stakeholders should focus on cancer patients’ stigma and self-perceived burden, enhance their focus on psychological resilience, and offer appropriate interventions and treatments for cancer patients with stigma and self-perceived burden.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to preserve the anonymity of the respondents but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

References

Belcher, S. M. et al. Financial hardship and quality of life among patients with advanced cancer receiving outpatient palliative care: A pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 46(1), 3–13 (2023).

Suarez-Almazor, M. et al. Quality of life in cancer care. Med 2(8), 885–888 (2021).

Mulasi, U. et al. Nutrition status and health-related quality of life among outpatients with advanced head and neck cancer. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 35(6), 1129–1137 (2020).

Hiratsuka, Y. et al. The association between changes in symptoms or quality of life and overall survival in outpatients with advanced cancer. Ann. Palliative Med. 11(7), 2338–2348 (2022).

Mohlin, Å. et al. Psychological resilience and health-related quality of life in Swedish women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 12041–12051 (2020).

Öcalan, S. & Üzar-Özçetin, Y. S. The relationship between rumination, fatigue and psychological resilience among cancer survivors. J. Clin. Nurs. 31(23–24), 3595–3604 (2022).

Gao, Y., Yuan, L., Pan, B. & Wang, L. Resilience and associated factors among Chinese patients diagnosed with oral cancer. BMC Cancer 19(1), 447 (2019).

Ejder, Z. B. & Sanlier, N. The relationship between loneliness, psychological resilience, quality of life and taste change in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 31(12), 683 (2023).

Boškailo, E. et al. Resilience and quality of life of patients with breast cancer. Psychiatr. Danub. 33(Suppl 4), 572–579 (2021).

Yang, G., Shen, S., Zhang, J. & Gu, Y. Psychological resilience is related to postoperative adverse events and quality of life in patients with glioma: A retrospective cohort study. Transl. Cancer Res. 11(5), 1219–1229 (2022).

Ye, Z. J. et al. Predicting changes in quality of life and emotional distress in Chinese patients with lung, gastric, and colon-rectal cancer diagnoses: The role of psychological resilience. Psychooncology 26(6), 829–835 (2017).

Aukst Margetic, B., Kukulj, S., Galic, K., Saric Zolj, B. & Jakšić, N. Personality and stigma in lung cancer patients. Psychiatr. Danub. 32(Suppl 4), 528–532 (2020).

Bédard, S. et al. Stigma in early-stage lung cancer. An. Behav. Med. 56(12), 1272–1283 (2022).

Johnson, L. A., Schreier, A. M., Swanson, M., Moye, J. P. & Ridner, S. Stigma and quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 46(3), 318–328 (2019).

Snyder, S. et al. Moderators of the association between stigma and psychological and cancer-related symptoms in women with non-small cell lung cancer. Psychooncology 31(9), 1581–1588 (2022).

Cho, S. & Ryu, E. The mediating effect of resilience on happiness of advanced lung cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 29(11), 6217–6223 (2021).

Huang, Z., Yu, T., Wu, S. & Hu, A. Correlates of stigma for patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 29(3), 1195–1203 (2021).

Chen, X., Wang, Z., Zhou, J. & Li, Q. Intervention and coping strategies for self-perceived burden of patients with cancer: A systematic review. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 10(6), 100231 (2023).

Chen, X., Wang, Z., Zhou, J., Loke, A. Y. & Li, Q. A scoping literature review of factors influencing cancer patients’ self-perceived burden. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 68, 102462 (2024).

Eyni, S. & Mousavi, S. E. Intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive fusion, coping self-efficacy and self-perceived burden in patients diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology 32(5), 800–809 (2023).

Kim, S. H., Seo, M. S., Hwang, I. C. & Ahn, H. Y. Factors associated with self-perceived burden among terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 33(1), e6258 (2024).

Yeung, N. C. Y., Lu, Q. & Mak, W. W. S. Self-perceived burden mediates the relationship between self-stigma and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 27(9), 3337–3345 (2019).

Zhang, Z. L. et al. Influence of financial toxicity on the quality of life in lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy: The mediating effect of self-perceived burden. Cancer Manag. Res. 16, 1077–1090 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. The Relationship between self-perceived burden and posttraumatic growth among colorectal cancer patients: The mediating effects of resilience. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 6840743 (2019).

Zhang, X., Zhang, H., Zhang, Z., Fan, H. & Li, S. The mediating effect of resilience on the relationship between symptom burden and anxiety/depression among Chinese patients with primary liver cancer after liver resection. Patient Prefer Adherence 17, 3033–3043 (2023).

Ting, C. Y. et al. Self-perceived burden and its associations with health-related quality of life among urologic cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 29(4), e13248 (2020).

Xiaodan, L., Guiru, X., Guojuan, C. & Huimin, X. Self-perceived burden predicts lower quality of life in advanced cancer patients: The mediating role of existential distress and anxiety. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 803 (2022).

Zou, D. et al. Self-efficacy’s mediating role in the relationship between self-perceived burden and health-related quality of life among older-adult inpatients in China: A cross-sectional study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 17, 2157–2163 (2024).

Chang, Y. et al. Influence of self-perceived burden on quality of life in patients with urostomy based on structural equation model: The mediating effects of resilience and social support. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 9724751 (2022).

Zhang, N. et al. Illness uncertainty, self-perceived burden and quality of life in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 31(19–20), 2935–2942 (2022).

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J. & Short, S. D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8(4), 379–386 (2017).

Dessau, R. B. & Pipper, C. B. “R”-project for statistical computing. Ugeskr Laeger 170(5), 328–330 (2008).

Campbell-Sills, L. & Stein, M. B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma Stress 20(6), 1019–1028 (2007).

Wang, L., Shi, Z., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Z. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 64(5), 499–504 (2010).

Fife, B. L. & Wright, E. R. The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J. Health Soc. Behav. 41(1), 50–67 (2000).

Pan, A. W., Chung, L., Fife, B. L. & Hsiung, P. C. Evaluation of the psychometrics of the Social Impact Scale: A measure of stigmatization. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 30(3), 235–238 (2007).

Cousineau, N., McDowell, I., Hotz, S. & Hébert, P. Measuring chronic patients’ feelings of being a burden to their caregivers: Development and preliminary validation of a scale. Med. Care 41(1), 110–118 (2003).

Wu Yanyan, J. Y. Survey and analysis of self-perceived burden in cancer patients. J. Nurs. Adm. 10 (6), 405-407 (2010)

Aaronson, N. K. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85(5), 365–376 (1993).

Wan Chonghua, C. M., Zhang, C., Tang, X., Meng, Q. & Zhang, X. Review of the Chinese version of EORTC QLQ-C30, a quality of life measurement scale for cancer patients. J. Pract. Oncol. 4(20), 353–355 (2005).

Ting, C. Y. et al. Financial toxicity and its associations with health-related quality of life among urologic cancer patients in an upper middle-income country. Support. Care Cancer 28(4), 1703–1715 (2020).

Keles, A. et al. Exploring the influence of health and digital health literacy on quality of life and follow-up compliance in patients with primary non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A prospective, single-center study. World J. Urol. 43(1), 94 (2025).

Gastric cancer. Importance of surgical staging, tumour pathology, and quality of life. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 133, 1–106 (1987).

Robertson, S. M., Yeo, J. C., Sabey, L., Young, D. & MacKenzie, K. Effects of tumor staging and treatment modality on functional outcome and quality of life after treatment for laryngeal cancer. Head Neck 35(12), 1759–1763 (2013).

Mohlin, Å., Bendahl, P. O., Hegardt, C., Richter, C., Hallberg, I. R., Rydén, L. Psychological resilience and health-related quality of life in 418 Swedish women with primary breast cancer: Results from a prospective longitudinal study. Cancers (Basel) 13(9) (2021).

Zhang, Z., Stein, K. F., Norton, S. A. & Flannery, M. A. An analysis and evaluation of Kumpfer’s resilience framework. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 46(1), 88–100 (2023).

Franjić, D., Babić, D., Marijanović, I. & Martinac, M. Association between resilience and quality of life in patients with colon cancer. Psychiatr. Danub. 33(Suppl 13), 297–303 (2021).

Abdollahi, A. et al. Self-care behaviors mediates the relationship between resilience and quality of life in breast cancer patients. BMC Psychiatry 22(1), 825 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Psychological resilience, dyadic coping, and dyadic adjustment in couples dealing with cervical cancer in Northwest China: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 74, 102785 (2025).

Eker, P. Y., Turk, K. E. & Sabanciogullari, S. The relationship between psychological resilience, coping strategies and fear of cancer recurrence in patients with breast cancer undergoing surgery: A descriptive, cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 73, 102719 (2024).

Ulibarri-Ochoa, A., Macía, P., Ruiz-de-Alegría, B., García-Vivar, C. & Iraurgi, I. The role of resilience and coping strategies as predictors of well-being in breast cancer patients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 71, 102620 (2024).

Festerling, L. et al. Resilience in cancer patients and how it correlates with demographics, psychological factors, and lifestyle. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149(8), 5279–5287 (2023).

Lei, H. et al. The chain mediating role of social support and stigma in the relationship between mindfulness and psychological distress among Chinese lung cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 29(11), 6761–6770 (2021).

Mei, Y. et al. The impact of psychological resilience on chronic patients’ depression during the dynamic Zero-COVID policy: The mediating role of stigma and the moderating role of sleep quality. BMC Psychol. 11(1), 213 (2023).

Kim, N. et al. Effects of cancer stigma on quality of life of patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 27(2), 172–179 (2023).

Park, Y. M., Kim, H. Y., Kim, J. Y., Kim, S. R. & Choe, Y. H. Relationship between type D personality, symptoms, cancer stigma, and quality of life among patients with lung cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 57, 102098 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Cui, C., Wang, Y. & Wang, L. Effects of stigma, hope and social support on quality of life among Chinese patients diagnosed with oral cancer: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18(1), 112 (2020).

Sihvola, S., Kuosmanen, L. & Kvist, T. Resilience and related factors in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 56, 102079 (2022).

Ursin, H. & Eriksen, H. R. The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29(5), 567–592 (2004).

Lau, J., Khoo, A. M., Ho, A. H. & Tan, K. K. Psychological resilience among palliative patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review of definitions and associated factors. Psychooncology 30(7), 1029–1040 (2021).

Teo, I. et al. Perceived stigma and its correlates among Asian patients with advanced cancer: A multi-country APPROACH study. Psychooncology 31(6), 938–949 (2022).

Liu, X. H., Zhong, J. D., Zhang, J. E., Cheng, Y. & Bu, X. Q. Stigma and its correlates in people living with lung cancer: A cross-sectional study from China. Psychooncology 29(2), 287–293 (2020).

Luo, T. et al. Self-perceived burden and influencing factors in patients with cervical cancer administered with radiotherapy. World J. Clin. Cases 9(17), 4188–4198 (2021).

Saul, J. & Simon, W. Building resilience in families, communities, and organizations: A training program in global mental health and psychosocial support. Fam. Process 55(4), 689–699 (2016).

Thornicroft, G. et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet 387(10023), 1123–1132 (2016).

Oeki, M. & Takase, M. Coping strategies for self-perceived burden among advanced cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 43(6), E349-e355 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We express our great gratitude to the participants in the study.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the research: J-s X and LZ. Wrote the paper: J-s X. Analyzed the data: J-s X and LZ. Revised the paper: J-s X, LZ, L-l G, Z-y G, P-j J, Q-q J, M-j S, Y-a C, HS.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All individuals have provided informed consent before the data collection. Participating patients were promised that the information provided would remain anonymous. Approval for the study was obtained from the College of Nursing’s Research Committee at Jinzhou Medical University (JZMULL2022086), and all methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Gao, Z., Ji, P. et al. Relationship between psychological resilience and quality of life in cancer patients and the multiple mediating roles of stigma and self perceived burden. Sci Rep 15, 12375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96460-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96460-2