Abstract

Rural tourism is becoming more valued by different tourist destinations along with the expansion of its market, especially, ancient town tourism, as one of the special rural tourism destinations, has become popular in recent years. This study aims to take Shawan ancient town as a case to comprehend the role of soundscape perceptions in affecting both flow experience and memorable tourism experience and further influence future behavioral intentions. The method of systematic sampling was performed, and finally, 394 samples were retained for further PLS-SEM analysis. The results show that both natural soundscape perceptions and human-made soundscape perceptions have significant effects on flow experience and memorable tourism experience, and natural soundscape perceptions have a stronger effect on tourism experience. In addition, both flow experience and memorable tourism experience were found to influence behavioral intention positively, and flow experience shows the stronger impact. Findings provide managerial implications suggesting that destination managers should cleverly integrate natural soundscape elements into the design of ancient towns and reduce interference from human-made soundscapes. Additionally, practical implications are provided for destination managers in designing soundscapes in the ancient town.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rural tourism, often referred to as countryside or agritourism tourism, is popular worldwide (Lane 1994). According to the report from Future Market Insights (FMI 2023), the global rural tourism market will reach US$ 102.7 billion in 2023, and it can realize a steady 6.8% compound growth rate in the next decade. Rural tourists are increasingly seeking immersive experiences, a connection with nature, and an escape from the hectic urban life (Chen et al. 2023; Yildirim and Arefi 2022). As one special type of rural tourism, ancient town attractions offer a unique proposition (Su 2010). Ancient towns, as a continuum sitting on a spectrum from rural to urban areas that are characterized by rural functions (such as traditional, locally based, authentic, remote, and sparsely populated), provide the ideal backdrop for modern tourists (Lane 1994; Rosalina et al. 2021). As Orbasli (2002) underlined, ancient towns are traditionally dated back centuries, their rich historical heritage and picturesque settings are found to offer a stark contrast to the modernized and urbanized world. And these reasons contribute to the preference for ancient towns among rural tourists (Gao and Wu 2017). Therefore, rural tourism research, especially the ancient town as a specific tourism destination, has become an important destination topic that cannot be overlooked. Notably, as the popularity of ancient town tourism grows, there is a greater emphasis on its development trends, such as sustainable practices and collaborative conservation (Lane and Kastenholz 2015).

In research on rural experiences, sensory-related attractions are considered essential resources for a destination, and these sensory landscapes serve as important mediums for tourists to perceive the place (Agapito et al. 2014). Hence, more scholars have attempted to study the dimensions of sensescape in the tourism experience (Wong and Lai 2024). For example, previous studies concerned the impact of landscape and heritage buildings on the tourism experience in the ancient town (Fatimah 2015; Zhang et al. 2021). However, as Carneiro et al. (2015) argued, there is a large and complex group of non-visual elements that can stimulate tourist perception in rural destinations, and soundscape is one of the most important factors. Soundscape, introduced by Schafer in 1997, can be thought of as an auditory landscape. In the context of ancient towns, soundscapes refer to the collection of sounds in the area, encompassing both natural (e.g., rustling of leaves, chirping of birds) and human-made sounds (e.g., tolling of historic bells, traditional music) (Chen et al. 2021). These sounds not only contribute to a sense of serenity and harmony with nature but also reflect the daily lives and historical traditions of the local communities (Jiang et al. 2020; Mao et al. 2022). Hence, ancient town tourists are drawn to these tranquil and cultural soundscapes. Practically, destination stakeholders attach great importance to ancient town tourism and continuously in the preservation and enhancement of soundscapes (e.g., sound art installation and digital interpretation) (Qiu et al. 2018). These practices are designed to maintain the authenticity of these destinations and attract rural tourists seeking a connection with tradition and nature (Zhao and Li 2023).

The stimulus-organism-response (SOR) theory (Mehrabian and Russell 1974) is an effective theory for investigating the influence of ancient town-related soundscapes on tourists’ experience and behavior. The SOR logic aims to explain and predict how an environmental stimulus (S) provokes an individual’s cognitive and emotional states (O), and ultimately, initiates their behavioral responses (R) (Schreuder et al. 2016). Over recent decades, SOR literature suggested that the environment around tourists can affect their tourism experience through different senses, especially the auditory sense (He et al. 2019). For example, some studies showed that soundscape perceptions can trigger flow experience in visitors in a heritage old town (Lu et al. 2022), and some empirical research demonstrated the role of natural soundscapes in the formation of memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) (Bai et al. 2023; Kankhuni and Ngwira 2022). However, there are limited studies introducing it to explore whether both of them were intergraded works on behavioral intention of soundscapes of ancient towns. To be specific, as suggested by Kim and Thapa (2018), the flow experience tried to describe the on-site state that tourists fully engaged and filtered out all irrelevant perceptions when they absorbed in the soundscape environment. Kim (2018) observed that MTEs is more long-lived, which enables tourists to relive and continually reflect upon their experiences. Additionally, the above studies examined that both flow experience and MTEs positively influence WOM and revisit intentions in the soundscape setting. Hence, while flow experience and MTEs reflect different aspects of the tourist experience, they are also interconnected. Evidently, it is possible that these two types of tourist experiences are different and occur at the same context (Zatori et al. 2018). Above all, more than one type of tourism experience is worth studying for the research background of soundscapes in the ancient town.

In tourism, numerous studies generally reported important mediators such as satisfaction, destination image, and place attachment (Chi and Han 2021a; Chiang 2023). However, different scholars in recent studies argued that the commonly employed mediator in current tourism practices might not be sufficient. For example, Dolnicar et al. (2015) claimed that cultural tourists may have an exceptional experience in Egypt and rate it as satisfactory, but they will never return, since he/she might want to explore as many other novel attractions as possible around the world. Hence, more emerging mediators are needed because some traditional mediators (e.g., satisfaction, destination image) are not always applicable in certain scenarios. As Kim et al. (2023) proposed, in the experience economy, tourism experience is the core concept during travel. Conceptually, different from other factors like satisfaction, the tourism experience can be remembered and recalled. Hence, they are more valuable and unique while other factors may not have achieved the same level of being recalled. Therefore, in order to narrow down the academic focus, as well as examine the distinctive impact of two types of experiences, this study pays close attention to the direct relationships between tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in the proposed framework.

In summary, this study aims to identify the soundscape perceptions from ancient town sites and examine the effect of the soundscape perceptions on rural tourists’ behavioral intentions through flow experience and MTEs. The contributions of this study can be understood in four aspects. First, this study identifies the two-dimensional scale of soundscape perceptions in the ancient town, which enriches the knowledge for soundscape research in rural destinations. Second, this study combines and examines both flow experience and MTEs co-appearing and working together on the tourism experience of ancient towns. This work provides an attempt to investigate the complex interrelationship between tourist different types of experiences for future studies. Third, this examines the effect of soundscape perceptions on rural tourists’ behavioral intentions toward the ancient town, which helps researchers to understand the mechanism of the SOR model in determining rural tourists’ preferences. Finally, the result of this study provides management strategies to rural destination planners to enhance rural tourists’ experience with ancient town-related soundscape attractions in the modern tourism market.

Literature review

The S-O-R framework

The current study expounds on the principles of the S-O-R framework which was rooted in environmental psychology (Mehrabian and Russell 1974) to investigate the tourism experiences of tourists after their soundscape perceptions in the ancient town. According to the S-O-R framework, it suggests that the cues present in the environment act as stimuli that result in emotional and cognitive responses (Xia et al. 2023). This further causes attitudinal and behavioral responses. The S-O-R framework has been applied to tourism-related research over the past decade, such as theme parks (Chang 2014), and VR tourism (Kim et al. 2020). However, its application to investigate the effects of soundscape perceptions on tourist experiences in rural destinations remains scarce. In this study, natural soundscape perceptions and human-made soundscape perceptions represent the stimuli within the framework of the S-O-R model, which constitute the dimensions of soundscape. O stands for the intermediate variable organism, namely, human emotional state and cognitive state. In this context, flow experience and memorable aviotourism experience were selected to assess the internal states of tourists. Finally, behavioral intention was selected to assess their responses.

Ancient town-related soundscape perceptions

Ancient towns are very competitive and popular destination choices around the world (Wang et al. 2022). The ancient town can be defined as s city approved as a famous historical and cultural city that should have rich cultural relic resources and have high historical value or revolutionary significance by the Cultural Relics Protection Law of PRC issued in 1982 (Yin et al. 2019). Differentiating from other types of tourist destinations, ancient towns not only provide the most basic functions such as accommodation, meals, and transportation (Su et al. 2021), but they also have diverse and complex tourism resources (Guo and Sun 2016). Traditional and historic buildings reflect the relatively harmonious relationship between people and nature in the region and can support the residents’ unique social culture, system, lifestyle, nature, including soundscape (Bucurescu 2015). Furthermore, some natural landscapes such as primitive parks, mountains, and rivers are included in ancient towns (Baral et al. 2017), but most of the previous studies neglect other elements in sensory of ancient town studies.

In recent years, acoustic journals have particularly favored the study of soundscapes in indoor and outdoor spaces, and many studies have been conducted on perception and evaluation in rural tourism and ancient town tourism (Francomano et al. 2022), ISO standardized the definition of a soundscape from the Handbook of Acoustic Ecology in 2014 as “an acoustic environment that one person or one perceives or experiences and/or understands in context. Soundscape typically consists of many aspects that occur simultaneously or separately over time, there are many classifications of it by different scholars, some scholars were divided into three categories, namely biological, geophysical, and anthropogenic sounds (Pijanowski et al. 2011), however, according to Zhang et al. (2021), the study emphasizes the soundscape can be divided into natural soundscape and cultural soundscape, and based on Axelsson et al. (2014) defined the classification of soundscape named technology (e.g., road-traffic and other kinds of noise), nature (e.g., water sounds from the fountain and other kinds of natural sounds), and humans (e.g., voices), especially Ma et al. (2021) directly make a distinguish of soundscape elements that are three principal components “Natural sounds”, “Human-made sounds”, and “Mechanical sounds”. This paper mainly focuses on the positive effects of different types of soundscapes. Thus, natural soundscapes and human-made soundscapes are the key dimensions of research objects within soundscapes.

Natural soundscape refers to the group of each sound in nature, weather sounds such as snow, thunder, and rain; Insect sounds such as bird calls, worm calls, or running water (Pijanowski et al. 2011, p. 1214). More and more scholars pay attention to the study of tourism experience in the sensory dimension, and now natural soundscape is developed to be regarded as an important attribute of nature-based destinations and an ideal experience for nature-based tourism (Watts and Pheasant 2015). In addition, natural soundscape has been confirmed to give tourists positive feelings such as peace and relaxation, thus, the natural soundscape has been widely accepted as an important perception element of nature-based tourism destinations (Jiang et al. 2020). Human-made soundscapes can be defined as sound sources produced by human activities or those produced by human beings themselves (such as talking, shouting, or singing) (Qi et al. 2008). In this study, it also includes related to the destination including bells, hawking by small shop runners, various utensils, characteristic sounds of national musical instruments, radio or musical sounds, and so on (Ou et al. 2017). Human-made soundscapes may also include sounds such as children’s play, footsteps, and communication between residents or tourists; those sounds are not related to the attraction (Guo et al. 2022).

In the field of tourism, several studies have addressed soundscape descriptors and prediction models for soundscape were developed, for example, Zhang et al. (2021) proposed the five basic dimensions of everyday soundscape perception in spatiotemporal view and the study on the audio-visual evaluation of the traditional national sound “Dong Grand Song” and made comparative research (Mao et al. 2023). However, previous studies usually focused more on the impact of natural soundscapes on tourists’ emotions and perceptions, even soundscape research on human-made soundscapes is usually negative, such as damaging experience and reducing satisfaction (Francis et al. 2017). Still unclear is to what degree these soundscapes as acoustic beacons for tourism destinations and whether they influence tourism experience in ancient towns.

Tourism experience

Tourism experience has a long and rich history of research and critical discussion, in fact, it can be said to be one of the most central questions or issues in tourism research (Stienmetz et al. 2021). The concept of tourism experience refers to the personal tourism experience as the emotions that visitors perceive during their visit, which explains their immersion in and satisfaction with the experience (Lunardo and Ponsignon 2020, p. 1152). In the study of destination travel, the tourism experience is generally classified into two main streams, for instance, Agapito et al. (2013) developed an empirical study on the sensory dimension of travel experience, and Huang et al. (2020) studied the positive enhancement of virtual reality on travel experience based on flow theory. Some scholars have proposed various dimensions of tourist experience in the same scene of tourism. In an experience study of national parks, Bigne et al. (2020) classify tourist experiences as MTEs or OTEs (ordinary tourist experiences). In addition, MTEs and OTEs are compared to identify any significant differences between their dimensions. Yan et al. (2016) divided tourism experiences in a dark tourism space into emotional tourist experiences and cognitive experiences. Campón-Cerro et al. (2020) mentioned that experiences can be divided into two dimensions: participation and connection. Thus, in this study, tourism experience is divided into two dimensions: flow experience and memorable tourism experience.

Flow experience

Much research on flow experiences in consumer behavior, especially in the travel and leisure field (Chang 2014). Flow experience can be regarded as the best discussion of experience (Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre 1989), and it refers to a cognitive state of greater pleasure and excitement when experiencing or participating in an activity (O’Neill 1999, p. 130). It reinforces the value and importance of positive psychology and flow in each experience a visitor has.

Flow experience has been improved in past sensory research that individual experience is determined by the physical response of the person’s body to the surrounding environment (e.g., Seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, and tasting) (Lugosi and Walls 2013). The ability of the senses to enhance the visitor experience has been supported by much evidence in the past (Agapito et al. 2013). Lu et al. (2022) suggested that tourists’ perception can be regarded as a crucial factor, especially in a stimulating physical environment and the flow experience is positively related to visitor’s perception. During the process of traveling in tourist destinations, soundscapes can make tourists deeply involved in the experience, thereby creating a pleasant psychology or making it easier for tourists to feel immersive (Loepthien and Leipold 2022). Tourists can concentrate more on experience which means that the psychological experience has been produced (Snyder and Lopez 2001). Besides, referring to the literature review, soundscapes can be divided into natural soundscape perception and human-made soundscape perception. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a. Natural soundscape perceptions will positively influence the flow experience.

H1b. Human-made soundscape perceptions will positively influence the flow experience.

Memorable tourism experience

Creating memorable consumer experiences is more valuable than other products and services (Wong and Lai 2021; Zhou et al. 2022), it helps producers become more competitive. Tung and Ritchie (2011) investigated several aspects of creating a memorable travel including affection, consequentiality, and recollection and others. A memorable tourism experience (MTE) is defined as “a tourism experience that is positively remembered and recalled after the event has occurred” (Kim et al. 2012). Therefore, MTE is an experience that is selectively recalled from the travel experience and recognized and recalled after the trip. Extraordinary travel experiences or memories with highlights will be easier to remember than ordinary trips (Hosseini et al. 2023; Wong et al. 2019).

Previous studies examined the positive relationship for overland tourists between natural soundscape perceptions and memorable tourism experiences (Kankhuni and Ngwira 2022). Besides, some studies indicated the relevance of the sensory is crucial to a memorable tourism experience (Agapito et al. 2017). On the whole, in quantitative research, few studies use soundscapes to investigate the role of forming memorable travel experiences. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a. Natural soundscape perceptions will positively influence memorable tourist experiences.

H2b.Human-made soundscape perceptions will positively influence memorable tourist experiences.

Instead of consuming to meet tourists’ needs, travel consumers are looking for experiences that “activate emotions”, “engage processes”, “touch hearts”, and “awaken minds” now (Hosany and Witham 2010). Among these mental processes, one of the concepts that can clarify an individual’s mental state during the experience in the context of activity is the mental process called “flow experience” (Ferrara et al. 1997). Consumers are more likely to seek out and participate in those events which are unique, unusual and memorable (Ayazlar 2015). Wei et al. (2019) found that the recollection of MTE was positively affected by involvement. Zatori et al. (2018) revealed that flow, as a dimension of experiential involvement, can affect memorability. Chen et al. (2020) adopt flow as the “fun” scale by which to capture tourists’ emotional response to the tourism experience and attempt to study the relationship between fun and MTE. Therefore, the hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Flow experience will positively influence memorable tourism experiences.

Behavioral intention

Past tourism studies have extensively proved the relationship between different and diverse factors and behavioral intention, such as satisfaction, perceived quality, brand value, and so on (Lai and Wong 2024; Ng et al. 2023; Zhou et al. 2023). Additionally, these factors will directly or indirectly affect customer loyalty, positive word of mouth, and re-visit willingness (Lai et al. 2022; Williams and Soutar 2009). Destination satisfaction refers to the overall evaluation of all activities and experiences of tourists during their visit to a destination (Cole and Scott 2004) and it is usually used to measure the quality and performance of a destination (Acharya et al. 2023). The revisit intention is defined as the willingness of tourists to visit the same destination again in the future and has a more important impact on destination loyalty. Therefore, when measuring the indicators of tourists’ future behavior, it needs to pay attention to the direct influence of satisfaction, re-visit index, and word-of-mouth (Kozak et al. 2005).

This study indicates the influence of two categories of tourism experience on behavioral intention. Among them, flow experience involves aspects such as satisfaction and happiness and aspects such as trust and loyalty, which are related to the evaluation of tourism product performance and experience (da Silva deMatos et al. 2021). Previous studies have supported that when tourists travel offline, memorable tourism experiences will positively affect tourists’ satisfaction, revisit intention and recommendations (Wong et al. 2020). Sthapit et al. (2019) confirmed that memories of past travel experiences contribute to tourists’ subjective well-being (Rasoolimanesh et al. 2022). The above discussions frame the following hypotheses:

H4a. Flow experience will positively influence behavioral intention.

H4b. Memorable tourism experiences will positively influence behavioral intention.

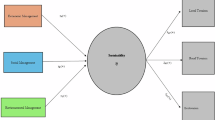

So, the conceptual model and proposed hypotheses are shown in Fig. 1.

Research method

Site selection and measurement

The research site was selected in Shawan Ancient Town (located in the northwest of the Pearl River system in Guangdong Province, China), a Lingnan cultural water town with a history of over 800 years. This study identified three sampling areas along the main tourist routes to ensure that there were visitors, including Baomo Garden, Shouwang Tower, and Aoshan Ancient Temple Group. As a famous natural and cultural tourist destination, these sampling areas contain abundant natural and human-made soundscape elements in Shawan Ancient Town. For example, there are folk bands who perform local music on the streets of ancient buildings, accompanied by residents slowly strolling and chatting in the dialect that fills the atmosphere of the ancient town. Meanwhile, in the gardens, tourists can naturally hear the pool water flowing slowly. When tourists stop to rest, they can even hear the wind rustling through the fallen leaves and the ethereal chirping of birds. These healing sounds immerse tourists and evoke profound sensory impressions.

The framework dimensions of ancient town-related soundscapes (ATSP) were inspired by Zhang et al. (2018)’s study recording various sounds heard in Han Buddhist temple setting. And the scale for measuring ATSP in this study, regarding the natural soundscape perceptions (NSP) and human-related soundscape perceptions (HSP), is derived and revised from Kankhuni and Ngwira (2022) to fit into the ancient town context. The scale for measuring flow experience was revised by Kim and Thapa (2018). The scale for measuring memorable tourism experiences was borrowed from Kankhuni and Ngwira (2022). According to behavioral intention, the measuring scale was adapted from Jiang (2022). The measurement items were initially written in English and translated into Chinese and then translated back into English by two professional translators to verify consistency. In early February 2023, a pilot test was conducted on 30 Chinese tourists on sites to establish content validity. All tourists who participated in the pilot test confirmed that they understood exactly the meaning of the measurable items, hence no further modifications were made. Besides, the content proofreading work was completed by two professors in tourism. Finally, all thirty pilot samples were excluded from the formal further statistical analysis. These measurable items are shown in Table 1.

Questionnaire design and data collection

The questionnaire includes three main sections. Firstly, as the sampling units are closely integrated with the local community, a scan question “Are you a tourist to the Shawan ancient town?” was set to ensure the respondents. The second section contained 18 questions measuring the five constructs of the conceptual model on a seven-point Likert scale. Each item is measured by a seven-point Likert-type scale, anchored by 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”. Besides, in front of the section of natural/ human-made soundscapes questions, there is a paragraph of words illustrating clear definitions and examples to ensure respondents’ understanding of the researched objects. Finally, the third section is the background profile, including respondents’ gender, age, education, income, and frequency (see Table 6 in the Appendix).

The survey was conducted from Feb 20 to Mar 12 with a total of 21 days. The survey sites are mainly located at three top attractions in Shawan ancient town in Guangzhou, including Baomo Garden (1st week), Shouwang Tower (2nd week), and Aoshan Ancient Temple Group (3rd week). These three sites have a rich content of ancient town-related (including natural and human-made) sounds for tourists to generate their soundscape perceptions. Referring to Wang et al. (2023) process, systematic sampling was used in this study, which is a frequently employed probability sampling technique in the field of tourism research. Compared with non-probability sampling methods like convenience sampling, systematic sampling helps mitigate the inherent biases that might be present in convenience sampling (Sharma 2017). With the random number 6 was drawn from the mobile device App (the Random Number Generator), every six person was approached to participate in this survey. Besides, only people above 18 years are targeted to be appropriate for the survey. In cases where the targeted tourists declined to participate in the survey, the research assistants postponed the survey until the arrival of the 6th subsequent tourist. The data of the questionnaires were collected face-to-face by eight well-trained research assistants from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. every day, supervised directly by the researchers of this study. The measurement items are originally written in English. To verify the consistency of the survey instrument, the back-translation process suggested by Bracken and Barona (1991) was employed by two professional translators. Each participant took around 20 min to complete one questionnaire. In total, 421 samples were collected. According to Wong et al. (2020)’s criteria of invalid data, 27 samples were judged useable due to incomplete questionnaires or providing the same rating to most of the questions. Finally, as shown in Table S1, 394 samples (including foreign samples 32 and 362 Chinese samples) were retained for further statistical analysis.

Findings

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) by performing SmartPLS version 3.3.3 (Ringle et al. 2015) was conducted to evaluate the structural model and test the hypothesis. The reason to choose PLS is because that program is an effective statistical technique used to detect relationships between variables in theoretical models (Hair et al. 2011). Also, PLS exerts less restrictive assumptions about normality and is appropriate for handling small samples. Following Hair et al. (2017), 394 cases and 5000 samples were used to perform bootstrapping to assess the significance of the path coefficients for the conceptual model.

Reliability and validity of the measures

As suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) recommended approach, this study tests the reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity of each construct before examining the structural model. The mean, standard deviation, and PLS factor for all 18 measurable items are presented in Table 1. The values of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) exceed the acceptable level of 0.7 (ranging from 0.812 to 0.925 and from 0.889 to 0.947, respectively), therefore indicating all constructs in this study have adequate reliability (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The PLS factor loadings for each measurable item are greater than 0.7, which ranged from o.799 to 0.910, and are hence all considered acceptable. Furthermore, the values of the average variance extracted (AVE, ranging from 0.728 to 0.816) of all the constructs are larger than the minimum criteria of 0.5. Subsequently, so the model achieves the satisfying standard convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Discriminatory validity is assessed based on the ratio of extracted variance in each variable to the square of the coefficients, indicating that it is statistically distinct from the other variable (Hair et al. 2017). Additionally, the values of each variance extracted are higher than the squared corresponding correlation estimate, and shared variances between twain of latent variables are less than the square root of the respective AVE. Hence, the empirical evidence of discriminant validity is illustrated in this study (see Table 2).

Structural model and hypothesis testing

The results of PLS-SEM analysis are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 3. The path coefficient from two dimensions of ancient town-related soundscape perceptions (ATSP), including natural soundscape perceptions (NSP) and human soundscape perceptions (HSP), to flow experience are 0.680 (p value < 0.001) and 0.195 (p value < 0.01). Thus, hypotheses H1a, and H2b are supported. The path coefficients from the two dimensions of ATSP are 0.327 (p value < 0.001) and 0.252 (p value < 0.01), supporting hypotheses H2a and H2b. Additionally, the path coefficient from flow experience to memorable tourism experience is 0.323 (p value < 0.001), indicating that hypothesis H3 is supposed. The path coefficient from tourist experience (flow experience and memorable tourism experience) to behavioral intention is 0.568 (p value < 0.001) and 0.280 (p value < 0.001). Hence, all the above hypotheses are supported. Furthermore, given the concern that common method bias may lead to deflation or inflation of observed relationships between variables (Kock 2015). The results of the PLS algorithm also include the value of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for all independent variables to assess any multicollinearity issues. The results reveal that all the values of VIF (ranging from 2.062 to 3.559) fall below the established threshold of 5, thus indicating the absence of problematic levels of collinearity (James et al. 2014).

To report the indicator of model fit criterion, the coefficients of determination (R-square), Stone–Geisser Q square, and effect sizes (f-square) for all constructs are presented in Table 4. R-square represents the variance explained in each of the endogenous constructs, are also referred to as in-sample predictive power (Chin 1998). The results show that R-square values for flow experience, memorable tourism experience, and behavioral intention are 0.691, 0.679, and 0.644, respectively, which are both much higher than the suggested criterion of 0.26. Thus, the model’s explanatory power is substantial (Cohen 1988). To better estimate the explanatory value, the change in R-square is estimated if a given exogenous construct is removed from the model. This measure is referred to the effect size (f-square), which assesses how much an exogenous latent construct contributes to an exogenous latent construct R-square value (Hair et al. 2011). The results revealed that the f-square effect size ranged from 0.060 (weak) for HSP on FE to 0.726 for NSP on FE (high). Finally, as a frequently used metric of out-of-sample prediction, the Stone–Geisser’s Q-square was assessed (Hair et al. 2019). According to Hair et al. (2013)’s thresholds evaluation criteria: 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 for weak, moderate, and strong effects. The values of Q-square in this study establish the strong degree of predictive relevance of endogenous constructs. Above all, these indicators validate the considerable model fit.

Mediation effects

This study examined the specific indirect and total effects in PLS using the process of bootstrapping (with 394 observations in each subsample and 5000 sub-samples) and a 95% confidence interval analysis. The variance accounted for (VAF) method was employed to examine the strength of the individual mediation effects. The results as presented in Table 5 suggested that FE played a mediating role in the relationship between two constructs of ATSP (NSP and HSP) and MTE (Path 1: IE = 0.220***, TE = 0.547***, 2.5% interval = 0.096 > 0; Path 2: IE = 0.063*, 0.315***, 2.5% interval = 0.022 > 0). The VAF of NSP and HSP are 0.402 and 0.200, respectively. In accordance with the criteria suggested by Hair et al. (2017), since the VAF values are between 20% and 80%, mediation paths 1 and 2 are both identified as partial mediations. Additionally, the effect of FE on BI through the mediation of MTE (Path 3: IE = 0.091**, TE = 0.659***, 2.5% interval = 0.036 > 0) had the value of VAF below 20% (13.8%), indicating that MTE has no mediating role between FE and BI.

Discussion and implications

Discussion

The results of this study identified a measurement scale of soundscape perceptions, encompassing both natural and human-made dimensions, within the context of rural tourism destinations. These two dimensions are aligned with the assertions made by Ma et al. (2021) that environmental soundscape preference in public urban space should consider the principal components, including “Natural sounds” and “Human-made sounds”.

The results of hypotheses H1a and H1b confirmed existing research that ancient town-related soundscape perceptions have significantly positive impacts on the flow experience (Lu et al. 2022). However, different from existing studies that focus on only one type of soundscape, especially the natural soundscapes (Jo and Jeon 2020), this study further discussed how these two types of soundscape perceptions (NSP and HSP) work together to influence the flow experience. Additionally, the finding showed that natural soundscape has a stronger impact on the flow experience. As Qiu et al. (2021) stated, the inherent calming and attention-restoring qualities of natural sounds contribute to reduced distractions, and immersion in the present moment, aligning with the key principles of flow theory. Additionally, according to Lu et al. (2022), in most cases, tourists can appreciate the human-made local music, and find a sense of control or softness in a harmonious and non-intrusive ambiance.

The results of hypotheses H2a and H2b confirmed that compared with human-made soundscapes, natural soundscape perceptions have stronger effects on tourist MTEs, which is consistent with Kankhuni and Ngwira (2022) study. That is, the natural sounds tend to evoke distinct auditory image features in their memory, enhance emotional engagement, and create lasting memories through the sensory richness of nature. Additionally, hypothesis H3 demonstrated that two types of tourist experiences are positively associated, which is neglected in the previous studies. Although there are research indicates that emotional components such as pleasure and excitement help people to remember the journey (Ding and Hung 2021). In this study, it is proven that both flow experience and MTEs occur in the soundscape environment of an ancient town. Specifically, on-site immersion experience will impact post-travel experience recall.

This study also confirmed (H4a and H4b) that these two types of tourist experience positively influence tourist behavioral intentions toward the ancient town. These findings are aligned with the previous studies regarding flow experience and MTEs (Ding and Hung 2021; Kim 2018). Significantly, some extent studies have indicated that the relationship between tourists’ experience and their behavioral intention is mediated by certain important variables, such as satisfaction and place identity (Chi and Han 2021b; Jiang and Yan 2022). With the main focus on showing the significant differences in the direct influence of two types of tourist experiences on behavioral intention, this study did not take such mediation factors into consideration. According to the results, tourist flow experience has a stronger effect than MTEs on positive behaviors, such as oral evaluation and revisit intentions. This finding implies that the flow experience within soundscapes can generate profound and sustained experiential behaviors, underscoring its significance for soundscape studies. Moreover, the discovery also advanced the prior observation with single-type experience in various tourism fields.

Theoretical implications

First, inspired by Zhang et al. (2018)’s study of recording various sounds heard in Han Buddhist temple settings, this study identified a two-dimensions scale of ancient town-related soundscape perceptions (including natural and human-made soundscape perceptions) in the rural tourism destination. Although understanding rural tourists’ soundscape perceptions in ancient towns is important, previous studies have not verified a measurement scale. Referring to Kankhuni and Ngwira (2022), this study amended appropriate measurement items that can reflect the natural and human-made elements in Shawan ancient town tourism, such as the rustling of leaves, chirping of birds, tolling of historic bells, and traditional music as shown in Table 1. Hence, this study highlights the rural tourist’s soundscape perceptions for traveling and provides a framework scale for researchers to take ATSP research.

Second, in tourism experiences research, most researchers have focused on tourism experience quality and single experience (Jiang et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2023). Researchers rarely notice that tourists may have different travel experiences in rural destinations, especially the ancient town. Hence, by combining two experiences in one scene, the attempt in this study enriched the knowledge of previous studies on tourist experience classification. At the same time, this study examined the positive interplay between on-site flow experience and post-travel MTEs, which indicated the potential connection, and achieved the theoretical integration between flow theory and memory theory.

Third, this study applied the SOR model to demonstrate the theoretical relationships between ancient town-related soundscape perceptions, flow experience, MTEs and behavioral intentions. This study showed a causal sequence from a stimulus (soundscape perceptions) to an intermediate organism (flow experience) transferring to another intermediate organism (MTEs) to a behavioral response (behavioral intentions toward an ancient town). Therefore, this study advanced the ___domain of soundscape tourism research by introducing a novel approach to building the SOR model. It elucidates an approach for enhancing a distinct form of rural tourism, notably emphasizing the promotion of ancient town tourism.

Finally, this study has potential contributions to interdisciplinary research. This interdisciplinary approach integrates elements of psychology, architecture, and tourism, fostering innovative design strategies that prioritize sensory aspects. By understanding how natural and human-made soundscape perceptions significantly enhance tourist experiences and behavioral intentions. Ultimately, this discovery provides new insights into tourism architectural design, not only in ancient town environments. Architectural designers can incorporate acoustic elements into their architectural design and consider esthetic issues.

Practical implications

This study offers insights into soundscape planning and management of ancient town environments or similar tourism attractions in rural destinations. First, given the important role soundscapes play in flow experiences when developing or designing an ancient town or other similar attraction, managers need to pay attention to the overall design of the soundscape and the content of these locations. On the one hand, managers should develop an awareness to preserve and enhance the natural soundscape of the ancient town. Ensure that the sounds of flowing water, birdsong, and rustling leaves are maintained to create a tranquil and immersive atmosphere. On the other hand, attraction managers can implement carefully crafted artificial soundscapes by incorporating ambient sounds like ancestral bells, local band performances, and folk songs. these measures foster a culturally rich and engaging atmosphere, elevating tourists’ connection to the historical setting and enhancing their overall flow experience.

Second, this study confirms that the soundscape of ancient towns is important in shaping MTEs after traveling. Managers therefore are expected to offer tourists novel soundscapes, especially those that are rare in urban life. On a practical level, managers need to protect biological diversity and allow tourists to hear a wider variety of harmonious natural sounds, such as the chirping of cicadas and crickets, or the sound of raindrops wetting leaves. Additionally, attractions should conduct workshops or demonstrations on traditional sounds, such as musical instrument making or local artisan techniques. This in-person activity allows tourists to have a novel and memorable experience of the ancient town’s culture through sounds heard. In addition, the ancient town can also introduce guided sound tours, allowing tourists to understand the importance of various sounds while exploring the ancient town. This knowledge can include the history of traditional music, as well as the stories behind specific natural sounds, which will help form long-term memories for ancient town tourists.

Additionally, attraction planning should focus on creating and enhancing tourists’ on-site flow experience and post-travel MTEs, as both two types of experiences have a positive impact on tourists’ behavioral intentions toward the ancient town. At this point, attraction planners can enhance tourists’ immersive experience in ancient towns by setting up sound equipment. In particular, managers can set up natural bird singing and fountain elements on spacious squares, and set up sound equipment in public areas, streets, bridges, and other places in ancient towns to play natural sounds. Creating a richer natural atmosphere increases pleasure and positive feelings so that tourists can experience the beauty of natural soundscapes and the unique charm of ancient towns. Regarding MTEs, today’s ancient town attractions can consider applying some information technology to produce some sound products. For example, some electronic audio albums include sound samples of the town’s unique sounds. These audio e-books are equipped with audio story descriptions, which not only become important mementoes of tourists’ soundscape experience but also remind tourists to return to the ancient town to find memories. Moreover, tourists can recommend the scenic spots in the destination to their friends by sharing the audio e-books, which also have a promotion function.

Limitations and future research

As with all studies, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the research concentrates on the relationship between soundscape and tourism experiences and ignores other sensory experiences such as sight, taste, smell, and touch. Future studies may expand on this current research by developing multidimensional measures for the evaluation of the tourist sensory experience that could potentially aid in the improvement of tourism experiences. Secondly, each region has different cultural backgrounds. This study only examined the ancient town of Shawan in China and the respondents were mainly Chinese domestic tourists. In fact, their soundscape perceptions may be different from those of international tourists. There are many other ancient towns in Asia or Europe, but the results of this study may not represent all destinations. Third, with a primary emphasis on highlighting substantial distinctions in the direct effect of two types of tourists’ experience on behavioral intention, this study did not consider other potential mediating elements (e.g., satisfaction or destination image). Hence, it is suggested that future studies could include such important mediations to verify the latent relationships between tourist experience and future behavioral intention. Lastly, this study compared the impact of natural and human-made soundscapes on the tourism experience in ancient town tourism destinations. Further studies are recommended to research the impact of soundscapes on tourism destinations with different functions, such as museums and amusement parks.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acharya S, Mekker M, De Vos J (2023) Linking travel behaviour and tourism literature: investigating the impacts of travel satisfaction on destination satisfaction and revisit intention. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 17:100745

Agapito D, Mendes J, Valle P (2013) Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. J Destin Mark Manag 2(2):62–73

Agapito D, Pinto P, Mendes J (2017) Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: in loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tour Manag 58:108–118

Agapito D, Valle P, Mendes J (2014) The sensory dimension of tourist experiences: capturing meaningful sensory-informed themes in Southwest Portugal. Tour Manag 42:224–237

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411

Axelsson Ö, Nilsson ME, Hellström B, Lundén P (2014) A field experiment on the impact of sounds from a jet-and-basin fountain on soundscape quality in an urban park. Landsc Urban Plan 123:49–60

Ayazlar RA (2015) Flow phenomenon as a tourist experience in paragliding: a qualitative research. Procedia Econ Financ 26:792–799

Bai W, Lai IKW, Wong JWC (2023) Memorable tourism experience research: a systematic citation review (2009–2021). SAGE Open 13(4):21582440231218902

Baral N, Hazen H, Thapa B (2017) Visitor perceptions of world heritage value at Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) national park, Nepal. J Sustain Tour 25(10):1494–1512

Bigne E, Fuentes-Medina ML, Morini-Marrero S (2020) Memorable tourist experiences versus ordinary tourist experiences analysed through user-generated content. J Hosp Tour Manag 45:309–318

Bracken BA, Barona A (1991) State of the art procedures for translating, validating and using psychoeducational tests in cross-cultural assessment. Sch Psychol Int 12(1–2):119–132

Bucurescu I (2015) Managing tourism and cultural heritage in historic towns: examples from Romania. J Herit Tour 10(3):248–262

Carneiro MJ, Lima J, Silva AL (2015) Landscape and the rural tourism experience: identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. J Sustain Tour 23(8–9):1217–1235

Campón-Cerro AM, Di-Clemente E, Hernández-Mogollón JM, Folgado-Fernández JA (2020) Healthy water-based tourism experiences: their contribution to quality of life, satisfaction and loyalty. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(6):1961

Chang K-C (2014) Examining the effect of tour guide performance, tourist trust, tourist satisfaction, and flow experience on tourists’ shopping behaviour. Asia Pac J Tour Res 19(2):219–247

Chen J, Huang Y, Wu EQ, Ip R, Wang K (2023) How does rural tourism experience affect green consumption in terms of memorable rural-based tourism experiences, connectedness to nature and environmental awareness? J Hosp Tour Manag 54:166–177

Chen M, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Wu K, Yang Y (2021) Rural soundscape: acoustic rurality? Evidence from Chinese countryside. Prof Geogr 73(3):521–534

Chen X, Cheng ZF, Kim GB (2020) Make it memorable: tourism experience, fun, recommendation and revisit intentions of Chinese outbound tourists. Sustainability 12(5):1904

Chi X, Han H (2021a) Performance of tourism products in a slow city and formation of affection and loyalty: Yaxi Cittáslow visitors’ perceptions. J Sustain Tour 29(10):1586–1612

Chi X, Han H (2021b) Emerging rural tourism in China’s current tourism industry and tourist behaviors: the case of Anji County. J Travel Tour Mark 38(1):58–74

Chiang YJ (2023) Multisensory stimuli, restorative effect, and satisfaction of visits to forest recreation destinations: a case study of the Jhihben National Forest Recreation Area in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(18):6768

Chin WW (1998) The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod Methods Bus Res 295(2):295–336

Cohen J (1988) Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl Psychol Meas 12(4):425–434

Cole ST, Scott D (2004) Examining the mediating role of experience quality in a model of tourist experiences. J Travel Tour Mark 16(1):79–90

Csikszentmihalyi M, LeFevre J (1989) Optimal experience in work and leisure. J Personal Soc Psychol 56(5):815

da Silva deMatos NM, de Sa ES, de Oliveira Duarte PA (2021) A review and extension of the flow experience concept. Insights and directions for Tourism research. Tour Manag Perspect 38:100802

Ding H-M, Hung K-P (2021) The antecedents of visitors’ flow experience and its influence on memory and behavioural intentions in the music festival context. J Destin Mark Manag 19:100551

Dolnicar S, Coltman T, Sharma R (2015) Do satisfied tourists really intend to come back? Three concerns with empirical studies of the link between satisfaction and behavioral intention. J Travel Res 54(2):152–178

Fatimah T (2015) The impacts of rural tourism initiatives on cultural landscape sustainability in Borobudur area. Procedia Environ Sci 28:567–577

Ferrara A, Barrett-Connor E, Shan J (1997) Total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol decrease with age in older men and women: the Rancho Bernardo Study 1984–1994. Circulation 96(1):37–43

FMI (2023) Rural tourism industry outlook (2023 to 2033). https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/rural-tourism-market

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Francis CD, Newman P, Taff BD, White C, Monz CA, Levenhagen M, Petrelli AR, Abbott LC, Newton J, Burson S (2017) Acoustic environments matter: synergistic benefits to humans and ecological communities. J Environ Manag 203:245–254

Francomano D, González MIR, Valenzuela AE, Ma Z, Rey ANR, Anderson CB, Pijanowski BC (2022) Human-nature connection and soundscape perception: insights from Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. J Nat Conserv 65:126110

Gao J, Wu B (2017) Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: a case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour Manag 63:223–233

Guo Y, Jiang X, Zhang L, Zhang H, Jiang Z (2022) Effects of sound source landscape in urban forest park on alleviating mental stress of visitors: evidence from Huolu Mountain Forest Park, Guangzhou. Sustainability 14(22):15125

Guo Z, Sun L (2016) The planning, development and management of tourism: the case of Dangjia, an ancient village in China. Tour Manag 56:52–62

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract 19(2):139–152

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2013) Partial least squares structural equation modeling: rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan 46(1-2):1–12

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Hair JF, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Sarstedt M (2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivar Data Anal 1(2):107–123

He M, Li J, Li J, Chen H (2019) A comparative study on the effect of soundscape and landscape on tourism experience. Int J Tour Res 21(1):11–22

Hosany S, Witham M (2010) Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J Travel Res 49(3):351–364

Hosseini S, Cortes Macias R, Almeida Garcia F (2023) Memorable tourism experience research: a systematic review of the literature. Tour Recreat Res 48(3):465–479

Huang X-T, Wei Z-D, Leung XY (2020) What you feel may not be what you experience: a psychophysiological study on flow in VR travel experiences. Asia Pac J Tour Res 25(7):736–747

James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R (2014) An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R. Springer Publishing Company, Inc

Jiang J (2022) The role of natural soundscape in nature-based tourism experience: an extension of the stimulus–organism–response model. Curr Issues Tour 25(5):707–726

Jiang J, Zhang J, Zheng C, Zhang H, Zhang J (2020) Natural soundscapes in nature-based tourism: leisure participation and perceived constraints. Curr Issues Tour 23(4):485–499

Jiang J, Yan B (2022) From soundscape participation to tourist loyalty in nature-based tourism: the moderating role of soundscape emotion and the mediating role of soundscape satisfaction. J Destin Mark Manag 26:100730

Jo HI, Jeon JY (2020) The influence of human behavioural characteristics on soundscape perception in urban parks: subjective and observational approaches. Landsc Urban Plan 203:103890

Kankhuni Z, Ngwira C (2022) Overland tourists’ natural soundscape perceptions: influences on experience, satisfaction, and electronic word-of-mouth. Tour Recreat Res 47(5-6):591–607

Kim JH, Ritchie JB, McCormick B (2012) Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J Travel Res 51(1):12–25

Kim JH (2018) The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviours: the mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. J Travel Res 57(7):856–870

Kim M, Thapa B (2018) Perceived value and flow experience: application in a nature-based tourism context. J Destin Mark Manag 8:373–384

Kim MJ, Lee C-K, Jung T (2020) Exploring consumer behaviour in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J Travel Res 59(1):69–89

Kim JH, Badu-Baiden F, Kim S, Koseoglu MA, Baah NG (2023) Evolution of the memorable tourism experience and future research prospects. J Travel Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875231206545

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J eCollab 11(4):1–10

Kozak M, Bigné E, Andreu L (2005) Satisfaction and destination loyalty: a comparison between non-repeat and repeat tourists. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 5(1):43–59

Lai IKW, Wong JWC (2024) Comparing the effects of tourists’ perceptions of residents’ emotional solidarity and tourists’ emotional solidarity on trip satisfaction and word-of-mouth intentions. J Travel Res 63(1):136–152

Lai IKW, Wong JWC, Hitchcock M (2022) A study of how LGBTQ tourists’ perceptions of residents’ feelings about them affect their revisit intentions: an emotional solidarity perspective. J Sustain Tour. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2130339

Lane B (1994) What is rural tourism? J Sustain Tour 2(1-2):7–21

Lane B, Kastenholz E (2015) Rural tourism: the evolution of practice and research approaches—towards a new generation concept? J Sustain Tour 23(8–9):1133–1156

Loepthien T, Leipold B (2022) Flow in music performance and music-listening: differences in intensity, predictors, and the relationship between flow and subjective well-being. Psychol Music 50(1):111–126

Lu Y-H, Zhang J, Zhang H, Xiao X, Liu P, Zhuang M, Hu M (2022) Flow in soundscape: the conceptualization of soundscape flow experience and its relationship with soundscape perception and behaviour intention in tourism destinations. Curr Issues Tour 25(13):2090–2108

Lugosi P, Walls AR (2013) Researching destination experiences: themes, perspectives and challenges. J Destin Mark Manag 2(2):51–58

Lunardo R, Ponsignon F (2020) Achieving immersion in the tourism experience: the role of autonomy, temporal dissociation, and reactance. J Travel Res 59(7):1151–1167

Ma KW, Mak CM, Wong HM (2021) Effects of environmental sound quality on soundscape preference in a public urban space. Appl Acoust 171:107570

Mao L, Zhang X, Ma J, Jia Y (2022) Cultural relationship between rural soundscape and space in Hmong villages in Guizhou. Heliyon 8(11):e11641

Mao L, Zhang X, Ma J, Jia Y (2023) A comparative study on the audio-visual evaluation of the grand Song of the Dong soundscape. Herit Sci 11(1):1–13

Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1974) An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press

Ng KSP, Zhang J, Wong JWC, Luo KK (2023) Internal factors, external factors and behavioural intention toward food delivery apps (FDAs). Br Food J 125(8):2970–2987

O’Neill S (1999) Flow theory and the development of musical performance skills. Bull Counc Res Music Educ 141:129–134

Orbasli A (2002) Tourists in historic towns: urban conservation and heritage management. Taylor & Francis

Ou D, Mak CM, Pan S (2017) A method for assessing soundscape in urban parks based on the service quality measurement models. Appl Acoust 127:184–193

Pijanowski BC, Farina A, Gage SH, Dumyahn SL, Krause BL (2011) What is soundscape ecology? An introduction and overview of an emerging new science. Landsc Ecol 26:1213–1232

Pijanowski BC, Villanueva-Rivera LJ, Dumyahn SL, Farina A, Krause BL, Napoletano BM, Gage SH, Pieretti N (2011) Soundscape ecology: the science of sound in the landscape. BioScience 61(3):203–216

Qi J, Gage SH, Joo W, Napoletano B, Biswas S (2008) Soundscape characteristics of an environment: a new ecological indicator of ecosystem health. In: Ji W (ed) Wetland and water resource modeling and assessment, CRC Press, New York, USA, pp 201–211

Qiu M, Jin X, Scott N (2021) Sensescapes and attention restoration in nature-based tourism: Evidence from China and Australia. Tour Manag Perspect 39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100855

Qiu M, Zhang J, Zheng C (2018) Exploring tourists’ soundscape emotion and its impact on sustainable tourism development. Asia Pac J Tour Res 23(9):862–879

Rasoolimanesh SM, Seyfi S, Rather RA, Hall CM (2022) Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour Rev 77(2):687–709

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J Serv Sci Manag 10(3):32–49

Rosalina PD, Dupre K, Wang Y (2021) Rural tourism: a systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J Hosp Tour Manag 47:134–149

Schreuder E, Van Erp J, Toet A, Kallen VL (2016) Emotional responses to multisensory environmental stimuli: a conceptual framework and literature review. SAGE Open 6(1):2158244016630591

Sharma G (2017) Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. Int J Appl Res 3(7):749–752

Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (2001) Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press

Sthapit E, Coudounaris DN, Björk P (2019) Extending the memorable tourism experience construct: an investigation of memories of local food experiences. Scand J Hosp Tour 19(4-5):333–353

Stienmetz J, Kim JJ, Xiang Z, Fesenmaier DR (2021) Managing the structure of tourism experiences: foundations for tourism design. J Destin Mark Manag 19:100408

Su MM, Yu J, Qin Y, Wall G, Zhu Y (2021) Ancient town tourism and the community supported entrance fee avoidance—Xitang Ancient Town of China. J Tour Cult Change 19(5):709–731

Su X (2010) The imagination of place and tourism consumption: a case study of Lijiang Ancient Town, China. Tour Geogr 12(3):412–434

Tung VWS, Ritchie JB (2011) Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann Tour Res 38(4):1367–1386

Wang M, Liu J, Zhang S, Zhu H, Zhang X (2022) Spatial pattern and micro-___location rules of tourism businesses in historic towns: a case study of Pingyao, China. J Destin Mark Manag 25:100721

Wang S, Lai IKW, Wong JWC (2023) The impact of pluralistic values on postmodern tourists’ behavioural intention towards renovated heritage sites. Tour Manag Perspect 49:101175

Watts GR, Pheasant RJ (2015) Tranquillity in the Scottish Highlands and Dartmoor National Park—the importance of soundscapes and emotional factors. Appl Acoust 89:297–305

Wei C, Zhao W, Zhang C, Huang K (2019) Psychological factors affecting memorable tourism experiences. Asia Pac J Tour Res 24(7):619–632

Williams P, Soutar GN (2009) Value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions in an adventure tourism context. Ann Tour Res 36(3):413–438

Wong JWC, Lai IKW (2021) Gaming and non-gaming memorable tourism experiences: how do they influence young and mature tourists’ behavioural intentions? J Destin Mark Manag 21:100642

Wong JWC, Lai IKW (2024) Same-sex romantic cruise experiences: the moderating effect of the personal openness trait. Leis Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2024.2302358

Wong JWC, Lai IKW, Tao Z (2019) Memorable ethnic minority tourism experiences in China: a case study of Guangxi Zhuang Zu. J Tour Cult Change 17(4):508–525

Wong JWC, Lai IKW, Tao Z (2020) Sharing memorable tourism experiences on mobile social media and how it influences further travel decisions. Curr Issues Tour 23(14):1773–1787

Xia Q, Wang S, Wong JWC (2023) The use of virtual exhibition to promote exhibitors’ pro-environmental behaviour: the case study of Zhejiang Yiwu International Intelligent Manufacturing Equipment Expo. PLoS ONE 18(11):e0294502

Yan B-J, Zhang J, Zhang H-L, Lu S-J, Guo Y-R (2016) Investigating the motivation–experience relationship in a dark tourism space: a case study of the Beichuan earthquake relics, China. Tour Manag 53:108–121

Yildirim Y, Arefi M (2022) Sense of place and sound: revisiting from multidisciplinary outlook. Sustainability 14(18):11508

Yin M, Xu J, Yang Z (2019) Preliminary research on planning of decentralizing ancient towns in small-scale famous historic and cultural cities with a case study of Tingchow County, Fujian Province. Sustainability 11(10):2911

Zatori A, Smith MK, Puczko L (2018) Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: the service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour Manag 67:111–126

Zhang D, Zhang M, Liu D, Kang J (2018) Sounds and sound preferences in Han Buddhist temples. Build Environ 142:58–69

Zhang H, Qiu M, Li L, Lu Y, Zhang J (2021) Exploring the dimensions of everyday soundscapes perception in spatiotemporal view: a qualitative approach. Appl Acoust 181:108149

Zhang M, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Luo N (2021) Effects of destination resource combination on tourist perceived value: in the context of Chinese ancient towns. Tour Manag Perspect 40:100899

Zhao ZF, Li ZW (2023) Destination authenticity, place attachment and loyalty: evaluating tourist experiences at traditional villages. Curr Issues Tourism 26(23):3887–3902

Zhou X, Ng SI, Ho JA (2023) Examining the relationships of destination image, memorable tourism experience and tourists’ behavioural intentions in ancient towns. Soc Space 23(1):313–348

Zhou X, Wong JWC, Wang SA (2022) Memorable tourism experiences in red tourism: the case of Jiangxi, China. Front Psychol 13:899144

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Macao Foundation (no. I01039-2309-077).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Supervision: JWCW; Conceptualization: JWCW; Methodology: WXBB; Investigation: YQ Guo; Formal analysis: WXBB; Data curation: JWCW; Original draft: WXBB, JJJW, XYHH and YQ Guo; Writing—review and editing: WXBB, JWCW, JJJW and XYHH; Visualization: WXBB; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The evaluation survey questionnaire and methodology were examined, approved, and endorsed by the research ethics committee of Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Macau University of Science and Technology (no. MUST-FTHM-2024-0024). The study meets the requirements of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tents of the declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

In this study, informed consent was duly obtained from all participants. Before any data collection commenced, participants were required to read and confirm the informed consent form. This form explicitly stated that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and responses would be anonymous and used solely for academic purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, W.(., Wang, J.(., Wong, J.W.C. et al. The soundscape and tourism experience in rural destinations: an empirical investigation from Shawan Ancient Town. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 492 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02997-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02997-4