Abstract

Religiosity and income have a multifaceted, complex relationship. Theories have different courses by which religion defines income, positively or negatively. However, religion and income can be influenced by many factors and vary between cultures and religious factions. This study aims to contribute to developing that understanding by focusing on Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim country. In this regard, we examine the impact of affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions on an individual’s income. This study utilizes data from the Pakistan Social and Living Standard Survey (PSLM) conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, spanning three time cohorts (2010–2011, 2014–2015, and 2019–2020) with sample sizes of 76,546, 78,635, and 195,000 households, respectively. we find that individual income varies significantly positively based on religiosity. Similarly, minority and minority interaction with religiosity significantly positively impact lone income in the studied context. These findings emphasize the need for nuanced understanding and consideration of cultural and religious factors when exploring the dynamics between religiosity and economic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The economics of religiosity is a growing field of study and is a promising area of academic inquiry since most of the world’s population is religious. Religion and economic behavior have been the subject of increasing study, but much remains unknown. Religion’s impact on economic conduct and commitment to materialistic wealth is especially crucial in developing countries, where the average incomes of impoverished and lower-middle-class households are growing. The extent to which these households become religious as they get wealthier will influence how their societies evolve (Beck and Gundersen, 2016). Religion plays a vital role in developing and implementing private institutions, such as family traditions and attitudes toward work and thrift, as well as state institutions, such as blue laws, prohibitions, and usury laws (Heath et al. 1995). This paper aims to investigate whether religiosity influences individual income in Pakistan.Footnote 1

Religion is integral to most people in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. According to government projections, Pakistan’s total population is estimated to be 234.4 million (PBS, 2020). As per the preliminary results of the most recent national census, 96 percent of the population is Sunni or Shia Muslim. According to government data, the remaining 4 percent include Ahmadi (who are not recognized as Muslims by national law); Hindus; Christians, including Roman Catholics, Anglicans, and Protestants; Parsis/Zoroastrians; Baha’is; Sikhs; Buddhists; Kalash; Kihals and Jains (PBS, 2020). Hence, it is believed that 4 percent of Pakistanis are members of a religious minority that are not Muslim. Therefore, this study emphasizes Islam as the studied religious denomination.

Behavioral economists make efforts to examine the causal relationship between religion and people’s economic behavior. Some notable scripts amongst them are: Buser (2015) examines the effect of income on religiousness in Ecuador; Lipford and Tollison (2003) investigate the bi-directional causal relationship between income and religious participation during 1971, 1980, and 1990 in USA; The bi–causal relationship between income and religion was scrutinized by Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2005) using data of 27,908 Dutch households in the Netherlands; Silveus and Stoddard (2020) identify the impact of income on religiosity with the moderating factor of Earned Income Taxed Credit in USA; Heath et al. (1995) scrutinize the causal relationship of religion and economic welfare in USA during the studied span of 1952, 1971, and 1980; Meredith (2012) examines the relationship between labor income and religiosity through survey data collected in USA from 1996 to 2004; Beck and Gundersen (2016) draw an analysis between earned income and religion in Ghana; Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2009) post examining income and religion, investigate religion and income: heterogeneity between twenty five western countries.

Empirical studies investigating the phenomenon have reached mixed conclusions. Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2005) found that religion positively affects income in the Netherlands. Specifically, they found that people who attend religious services regularly earn more than those who do not. Beck and Gundersen (2016) found that religious affiliation does not significantly affect income, but religiosity (i.e., the degree to which people practice their religion) does. In particular, their research revealed that individuals who engage in religious practices more frequently tend to have higher earnings compared to those who practice less frequently. Heath et al. (1995) found that religious affiliation positively affects income in the United States. Lipford and Tollison (2003) identified a direct association between religiosity and income within the studied US population, highlighting that individuals who exhibit higher church attendance tend to have higher earnings compared to those with lower attendance. Silveus and Stoddard (2020) discovered that religion has a positive impact on income in the United States, but this effect is limited to specific religious groups. Notably, Mormons and Jews tend to have higher earnings compared to non-religious individuals, whereas Protestants and Catholics do not exhibit a significant income advantage. The researchers further noted that disparities in education levels among religious groups contribute to the income advantage observed among Mormons and Jews. Lastly, Buser (2015) found that the relationship between religion and income varies across countries. While certain countries exhibit a positive correlation between religiosity and income, others demonstrate a negative correlation. Additionally, Buser found that differences in education levels across religious groups partly explain the relationship between religion and income.

Nonetheless, income inequality has always been challenging for developing economies, and Pakistan is no exception (Nielsen and Alderson, 1995). Income inequality has risen since 1970 in Pakistan (Kruijk and Leeuwen, 1985). Different studies have used standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and GINI coefficient to study income inequality in Pakistan. The studies show that income inequality has increased in rural and urban factions of Pakistan since the 1970s (Kemal, 1994; Awan and Hussain, 2007; and Cheema and Sial, 2012). In such an unbalanced situation, ethnic minorities usually suffer more from income inequality. What is the situation in Pakistan? Is there considerable income inequality between ethnic minorities and Punjabis (ethnic majority) in Pakistan? Does the role of religiosity in shaping lone income changes when interacting with ethnic minorities?

This research investigates the causal association between religion and income in a new context and with a different set of factors than earlier studies. Unlike previous studies on the subject, this study uses affiliation with deeni madrassa (orthodox Islamic institutions) as a surrogate measure of religiosity. As a result, we strive to offer insight into how being a part of a religious ecosystem impacts the economic well-being of individuals in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Based on the Pakistan Standard and Living Measurement Survey conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics in 2010–11, 2014–15, and 2019–20, this study uses data from three cohorts of respondents.

This study utilizes pooled OLS (with Huber—White estimator) and structural equation models to conclude that being associated with orthodox Islamic institutions (deeni madrassas) has a favorable influence on individual income, regardless of interaction with ethnic minorities in Pakistan. More precisely, after controlling for demographic characteristics and time cohorts, the study finds that affiliates of orthodox Islamic institutions in Pakistan earn significantly more than the other factions of the society. We interpret this finding as evidence that the role of these orthodox Islamic institutions is more of a social club rather than a mere education institute. They have built a robust ecosystem that provides their affiliates with free education and boarding and assists them in ensuring sustainable income throughout life. Moreover, religiosity, when interacting with ethnic minorities, has a significant positive impact on shaping lone income in Pakistan. We explain this as the network of these orthodox Islamic institutions is more established in the realms where ethnic minorities live.

We organize this paper as follows. “Literature Review and Hypotheses” examines different theoretical considerations and empirical literature supporting a causal relationship between religion and income. “Empirical Methodology and Data” discusses data, empirical models, summary statistics, and the estimation strategy. “Results and Discussion” debates the discussion of the results of religiosity shaping lone income. “Conclusion” provides concluding remarks.

Literature review and hypotheses

Religiosity and income have a multifaceted, complex relationship. Religion is related to income in several ways, depending on the context. Religion may indirectly stimulate individual wages through social networks, education, and job market experiences, all of which differ for members of religious groups (Lehrer, 1999; Keister and Sherkat, 2014). Religion may also directly impact income through beliefs and religious teachings related to a person’s income and financial prosperity (Bartkowski, 2014). In numerous contexts, religiosity and income share a positive correlation.

Theories have identified several paths by which religion defines income favorably or adversely Iannaccone (1992). Azzi and Ehrenberg (1975) were pioneers in deploying the neoclassical framework to elucidate the distribution of time between earning and religious activities. They suggested a utility model that includes consumption during one’s lifetime and after death. Religious activities (service attendance, monetary offerings, and so forth) are inputs to the afterlife production function. This model generates several testable and allegedly legitimate predictions, such as increased religious behavior later in life and increased religious engagement for people with lower opportunity costs. According to the concept, religious engagement should rise as non-wage income rises if afterlife consumption is a typical benefit.

A second theoretical paradigm considers religion a type of social insurance (Glaeser and Sacerdote, 2008; Gruber, 2005). Iannaccone (1992) established the classic economic model of religion, which analyzes religion as a clubhouse product with positive returns to “participatory crowding.” In this paradigm, more registered participants equate to a higher value for the club’s good. Religious organizations are incentivized to prevent free riding since the value of the good rises only with engaged participation. Efforts to combat free riding are used to justify rules such as dietary and dress restrictions, prohibitions on specific activities, and Sabbath observances. Religious groups’ insurance functions are widely established, and the optimal model of religiously provided social insurance suggests religious organizations will require a commitment to solving the free-rider problem (Buser, 2015). Individuals will respond to economic misery by indicating loyalty to religious groups if the insurance is provided ex-post (after some information about the risk has been revealed). Chen (2010) reveals evidence of this practice in Indonesian Muslim groups.

According to Chetty et al. (2014), religiosity is strongly positively correlated with upward mobility. Inclining upward mobility indicates a healthy economy, and job advancement is one of the key factors driving this economic advancement. This new research supports Iannaccone’s (1998) assertion that “religion is not the exclusive ___domain of the poor and uninformed”. One explanation is that religiosity boosts income by improving job networks, academic achievement, mental and physical stability, lower substance abuse, and a low divorce rate (Montgomery, 1991; Lim and Putnam, 2010; Hummer et al. 1999; Fruehwirth et al. 2019; Gruber and Hungerman, 2008; Gruber, 2005).

Disentangling the link between income and religion is complicated further by the fact that, in some instances, religion and income have a negative relationship rather than the positive one mentioned above. This negative link is found in cross-country scenarios where religious involvement and per capita GDP have a well-documented inverse relationship (Barro and McCleary, 2003; McCleary and Barro, 2006). According to Lipford and Tollison (2003), higher wages result in higher opportunity costs of attending religious services, thus resulting in less religious involvement. This argument is expanded and reinforced by Gruber and Hungerman (2008) and Hungerman (2014), who demonstrate that activities such as shopping or gaming are economical alternatives for religious service attendance and that service attendance decreases as opportunity costs increase. Other research suggests that formal religious ties may provide a social welfare system—informal insurance—against unfavorable economic circumstances. Dehejia et al. (2007) provide empirical evidence that individuals who donate to religious organizations report lower consumption declines after suffering adverse income shocks than those who do not donate. Chen (2010) investigates the impact of the 1997 Indonesian financial crisis and finds that consumption shocks promote religious intensity through Quran study and attendance at Islamic schools. Shaw et al. (2016) find evidence of increased church membership in counties that suffered damage during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. They attribute the rise to increased demand for social insurance. Religion appears to have an impact on salaries (Chiswick, 1983), education enrollment (Freeman, 2013), healthcare (Ellison, 1991), and criminal behavior (Ellison, 1991; Evans et al. 1995).

Some scholars have also investigated the issue by examining the effect of income on religiosity. Buser (2015) examined the religious practices of impoverished families in Ecuador after a change in eligibility criteria for a government cash transfer in 2010 and found that more social payments through the government’s cash transfer program were associated with a higher level of religious attendance. Similarly, Azzi and Ehrenberg (1975) argue that if afterlife consumption is typically considered beneficial, church attendance and financial donations to religious activities should increase as the non-wage income rises.

It is important to note that while this literature is thoughtful and valuable, it has some shortcomings. Firstly, the causality of the association between religion and income cannot always be determined with certainty due to endogeneity issues. Secondly, the literature is in general constrained to limited context (mostly developed countries) as shown in Table 1 below. Consequently, they cannot be extrapolated to other nations. Finally, the literature typically concentrates on the relationship between religion and outcomes. However, outcomes are not only influenced by attitudes but also by the surrounding environment. For example, in the United States, Catholics enjoy higher incomes (not as much as Jews, but higher than other religions). However, their success is widely linked to the high standard of their educational system. Thus, the interplay between the educational system and Catholic Church institutions in the United States, rather than Catholicism per se, could make people more successful in life. In Latin America, for example, it may not necessarily be true that Catholicism improves individual welfare (Guiso et al. 2003).

Furthermore, the relationship between affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions and individual income takes on a positive connotation when considering its interaction with ethnic minority status. While orthodox Islamic institutions traditionally function as vital social and economic networks, fostering support and opportunities for their members, this positive influence is magnified for individuals belonging to ethnic minority groups. In the face of obstacles confronting ethnic minorities in Pakistan, aligning with orthodox Islamic institutions emerges as a potent alleviating element, effectively mitigating the social and economic marginalization experienced by these minority groups (Shehzad, 2011; Sheikh and Gillani, 2023). This affiliation may play a crucial role in enhancing economic prospects for ethnic minorities, providing them with a sense of community, support, and increased access to mainstream opportunities. This positive synergy challenges existing notions of social stratification (Iannacone, 1998; Buser, 2015), suggesting that affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions contributes positively to individual income, especially within the unique dynamics of the Pakistani context. Further empirical exploration is essential to comprehensively understand and validate these positive associations, shedding light on the mechanisms that facilitate improved economic outcomes for ethnic minorities within this context.

The present study effectively addresses the issue of endogeneity by employing an alternative proxy to gauge religiosity, namely, the educational affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions (deeni madrassa), which individuals undertake prior to entering their professional endeavors. Additionally, the research centers its investigation on Pakistan, a nation belonging to the low-to-middle-income group, which has been overlooked in prior scholarly works. Furthermore, this study emphasizes Islam as the focus religious denomination, which has not been addressed in previous empirical studies. Through addressing these overlooked aspects, the study aims to contribute to the existing literature by providing a more comprehensive examination of the phenomenon. By focusing on the overlooked aspects, this study aims to fill the gaps left by previous research in understanding the phenomenon.

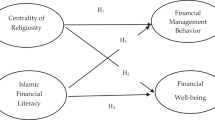

Building upon insights from empirical literature and theoretical discourse, the study posits, on balance, the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Active membership in orthodox Islamic institutions is expected to exert a significant positive impact on individual income.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The synergistic effect of being affiliated with orthodox Islamic institutions and belonging to an ethnic minority is hypothesized to significantly enhance individual income in a positive manner.

Empirical methodology and data

This section discusses data, specifies the empirical model, summary statistics, and motivates the estimation strategy.

Data

The data for this study is pooled from the Pakistan Social and Living Standard Survey (PSLM) conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). The data was collected for three-time cohorts: 2010–2011, 2014–2015, and 2019–2020. The PSLM survey in 2010–2011, 2014–2015, and 2019–2020 included a sample size of 76,546, 78,635, and 195,000 households, respectively, and provided information on a variety of demographic characteristics, including gender, age, ethnicity, employment, education, income, and regional distributions. These surveys were conducted through tablets based on android software with GIS for monitoring built by the data processing center, ensuring reliable and accurate data (PBS, 2020). This survey also pooled data for our focus independent variable religiosity, proxied by enrollment in deeni madrassas (orthodox Islamic institutions) in response to the survey question Sec C Q7 “What type of education institution was last attended?” with the following answer options: government, private, deeni madrassa, other qualifications, non-formal education, and NGO education.

The population for this study was the whole census population included in the PSLM surveys under consideration. However, the sample used for the analysis is restricted by the applicable exclusions. Initially, the study established an age floor of 14 years to exclude juveniles legally prohibited from working under the Islamic Republic of Pakistan’s constitution, as similar exclusions were made by Campos et al. (2016) in their study in China. Following that, observations with missing reporting incomes were excluded from each study cohort, accounting for 13.50% of the survey population, as Beck and Gundersen (2016) did in their study of the same phenomenon in Ghana and as Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2009) did in their study of 25 Western countries. Finally, 11% (47,250 individual subjects) of the remaining population (using convenience quota sampling) opted for conducting the analysis, which is also an empirically well–supported practice in scholarly circles when studying a census population.

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 summarizes the summary statistics for the study’s sample. The average age in the analyzed sample was found to be 24 years old. The gender distribution of the analyzed sample shows 47% female representation. The rural population, which accounts for 27.77% of the sample, resides in villages and rural vicinities. 67.46% of the sample represents the country’s minority ethnicities, which include Pashtun, Sindhi, Muhajir, Baluchi, Kashmiri, and Saraiki. 81.5% of the studied population are associated with paid employment and businesses while 18.5% of the population belongs to the strata of unpaid family workers. 40.2% of the research respondents were drawn from cohort I (2019–2020), 25.71% were drawn from cohort II (2014–2015), and 34.09% were drawn from cohort III (2010–2011). A total of 27.61% of the sample is drawn from the population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 36.81% is taken from the Punjab province, 27.11% from Sindh, and 8.47% comes from Baluchistan, the least populated province in Pakistan. The independent focus variable, 17.33% of the selected sample, attained their last education from an orthodox Islamic institution (deeni madrassa) in Pakistan. Finally, the average monthly per capita income observed for the studied cohorts was 59,205.85 PKR (equivalent to 367 USD as of the end of 2020).

Empirical model

For the purpose of this study, a baseline equation and an extended equation are formulated. The equation(s) are stated below: The equations are as follows:

(i)Baseline Equation

(ii)Extended Equation

Where LNINCO represents the natural logarithm of the monthly per capita income. LNAGE embodies the natural logarithm of the age of the research subjects. GENDER denotes 1 if the respondent is female and 0 otherwise. REGION encapsulates 1 if the respondent is a resident of a rural setting and 0 if vice versa. MINORITY condenses 1 for research subjects from ethnic minority factions and 0 for residents of the Punjabi bloc, the majority ethnic group in Pakistan. EMPLOY represents 1 for all paid employments and business while 0 denotes unpaid family workers. RELEDU designates 1 to individuals affiliated with an Orthodox Islamic Institution (deeni madrassa) and 0 for adults from other educational factions of the society, including government, private, deeni madrassa, other qualifications, non-formal education, and NGO education. TDI labels 1 as the first-time dummy variable representing the last studied cohort (2019–2020) and 0 otherwise. TDII tags 1 as the second time dummy variable that reflects the second last studied cohort (2014–2015) and 0 for the other time cohorts. PDI denotes 1 as the residents of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and 0 otherwise. PDII indicates 1 for the residents of the Punjab province and 0 for vice versa. PDIII specifies 1 as the residents of the Sindh province and 0 for the remaining three studied provinces. ε denotes the random error term, assumed to be typically and independently distributed. Furthermore, equation (ii) extends equation (i) with RELEDU x MINORITY, which represents the interaction of being a member of orthodox Islamic education (deeni madrassa) and belonging to a faction of ethnic minorities in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

The estimation of both equations is conducted using robust standard errors to alleviate the possibility of heteroscedasticity. The data used for this study are not affected by multicollinearity. The correlation table will be made available on request.

This study investigates whether the variable of interest RELEDU (captured by affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions) determines per capita income. A handful of empirical studies have examined the relationship between religiosity and income or another related variable, such as wages. Some notable scripts amongst them are Lipford and Tollison (2003) investigate the bi–directional impact of religiosity and income. The study found that religiosity has an insignificant negative impact on income. Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2005) analyze the impact of religion on income in 27,908 Dutch households. They found a significant negative impact of religious membership and participation on household income. Similar results were concluded in another study by Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2009), where they scrutinized the role of religiosity in shaping individual income in 25 western countries (mostly European countries, including New Zealand, Canada, and the USA). They found a significant negative influence of church membership on income. Iannaccone (1992) examines General Social Survey (GSS) data from 1983 to 1987 and discovers no link between family income and religious attendance frequency. Brañas-Garza and Neuman (2004) found no association using data from the Center for Sociological Research on Catholics in Spain from 1998. According to Iannaconne (1998), while wealth highly predicts religious donations, it is a poor predictor of other measures of religious engagement, such as church attendance, membership, and religious belief. Brown (2000), on the other hand, shows a statistically significant negative association between salaries and the frequency of religious attendance using GSS data from 1996 to 2004. However, the empirical findings were inconclusive because of the contextual limitation of focusing only on developed nations.

A distinctive feature of this study is that it examines affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions (deeni madrassa) as a proxy for religiosity in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan context. According to Blanchard (2008), madrassas are the leading Islamic institutions and a prominent measure of religious affiliation in the Muslim world. Madrassa institutions are famous in Pakistan for providing free education, lodging, and board to their affiliates, appealing to impoverished families and individuals to join this dense religious infrastructure. Therefore, it is expected that taking care of the basic needs of these Islamic institutions makes affiliated households less efficient at earning income. On the other hand, Cockcroft et al. (2009) advocate that the financial and social support madrassas provide to their members makes them save more and makes them able to create passive income-producing assets that eventually result in increasing income. This paper sheds some light on which of these two effects is dominant.

Additionally, the rationale behind adopting affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions as a proxy for quantifying religiosity in this study is congruent with established conventions in empirical literature that have employed church membership as a comparable indicator of religiosity (Buser, 2015; Heath et al. 1995; Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf, 2005; Lipford and Tollison, 2003). Within the framework of our exploration into Deeni Madrassas (Orthodox Islamic Institutions) in Pakistan, we draw parallels to the utilization of church membership, as these institutions function as educational and societal focal points, addressing financial, social, and spiritual needs akin to the communal roles of a church.

Moreover, we contend that the heightened religiosity discerned in individuals affiliated with orthodox Islamic institutions in Pakistan, relative to other societal segments, substantiates the appropriateness of this surrogate for our research objectives. It is acknowledged that, although the selected surrogate may lack perfection, it remains a widely accepted metric within the empirical literature.

Results and discussion

In Tables 3 and 4, this study presents the baseline and extended equation estimation results, respectively. In light of the inherent characteristics of the available data, we opt for employing Pooled Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) as the estimation technique, supplemented by the Huber-White estimator to account for heteroscedasticity. This decision is primarily influenced by the unavailability of a time-based trajectory for each research subject, which consequently precludes the incorporation of individual fixed effects. Notwithstanding this limitation, our efforts are directed towards mitigating potential unobserved heterogeneity to the best of our capability. This is achieved through the integration of controls for cohort fixed effects, region fixed effects, provincial fixed effects, and ethnic fixed effects.

Additionally, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is employed to replicate the analysis and tackle measurement error in the latent construct of religiosity (RELEDU). SEM captures the data’s underlying theoretical structure, assesses direct and indirect effects, and examines latent constructs. It takes advantage of a larger sample size resulting from data pooling, making it suitable for investigating complex relationships across diverse groups and time points. All variables, including RELEDU, were allowed to correlate in line with SEM conventions. The use of SEM in our study aligns with similar approaches taken by Lin (2019) and Becerra et al. (2013), strengthening the methodological foundation and providing additional support for our approach.

Non-focus independent variables

Apart from AGE and GENDER, all other factors are likely to substantially influence income in the examined sample during the analyzed cohorts. The variable REGION has a significant negative impact in determining income. This finding implies that people living in urban regions earn more in Pakistan than their counterparts living in rural areas. Like other developing countries, Pakistan has faced similar patterns of income disparity among regions (Khan and Sasaki, 2003). Like the urban areas of Pakistan, rural regions have also contributed to the nation’s growth during the past decades. However, gaps in income and education have contributed to this unequal regional prosperity in the country, as cited by Khan et al. (2015) and Khan and Idrees, 2014 in their studies. Moreover, since much of the rural population in Pakistan is associated with agriculture-related businesses, the consistent deprivation of the agricultural sector urges the population to migrate to urban centers in search of earning opportunities.

Furthermore, the variable MINORITY has a significant positive impact on income. This finding denotes that minority ethnicities, including Pashtun, Sindhi, Balochi, Saraiki, Kashmiri, and Muhajir, earn significantly more than the Punjabis, the ethnic majority of the country. Punjabis are mainly populated in the central and northern parts of the Punjab province. The northern and central parts of the province have heavily relied on agriculture-related businesses as their primary source of income (Farooq et al. 1999). Since the agriculture sector of Pakistan has been struggling for the last two decades, it directly impacts their residents’ income. Inadequate infrastructure, scarce supply of agricultural inputs due to depleting economic conditions, climate change, political instability, and shortage of agricultural finance are some mainstream reasons for poor agricultural output and eventually declining real income of the Punjabi ethnicities (Syed et al. 2022; Ahmed and Javed, 2016; Ullah et al. 2020; Chandio et al. 2018).

Additionally, EMPLOY has a significant negative impact on income. The finding encapsulates that unpaid family works earn more than paid employees and business employers during the studied cohorts in Pakistan. This advocates that Pakistan is a collectivist society where majority of the population lives in highly knitted family structures (Abbasi et al. 2015). Therefore, this is one reason that unpaid family workers may receive non-monetary benefits such as free housing, food, and other perks that can supplement their income. In some cases, these benefits are quite valuable, particularly in areas where housing and food costs are high. Since these benefits are not included in their income, it can make their earnings appear higher in comparison to other workers who do not receive such benefits (Khan, 2009). The findings of Shahnaz et al. (2008) study align with this perspective, asserting that the substantial rise in the prevalence of unpaid family labor, nearly doubling the overall employment rate in Pakistan, underscores significant concerns regarding the labor market characterized by pervasive underemployment and low-wage occupations. This trend prompts individuals to seek involvement in family-based agricultural enterprises, where they benefit from improved provisions such as food and lodging, ultimately contributing to an augmentation of overall household income. Furthermore, Felt and Sinclair (1992) posited analogous assertions in their research, suggesting that individuals facing unemployment or earning low incomes are more inclined to engage in the informal economy, exemplified by unpaid family work. This inclination arises from their challenges in securing essential living resources through wage labor, thereby leading them towards informal arrangements within family contexts to meet their needs.

Moreover, the time cohorts show a significant positive impact on shaping income. Comparing the Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) of Pakistan (2019/20 & 2014/15) to the benchmark cohort HIES (2010–11), a clear incline in per capita individual income has been reported during the last decade (PBS, 2020). Industrial development, expansion of the services sector, easier accessibility of funds, and increasing human capital have significantly contributed to bringing this inclining income trend to reality for the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, as cited by Akhtar et al. (2017); Afzal et al. (2020) & Rehman et al. (2022) in their studies.

Lastly, the province dummies PDI, PDII, and PDIII represent Punjab, KPK, and Sindh. They are benchmarked against the fourth province of the country, Baluchistan. The results show that residents of Baluchistan earn comparatively more than the other three provinces. According to the latest PSLM Survey (2018–2019), household income in Baluchistan is growing faster than in any other province. The average household income in Baluchistan had grown by 21% since 2014, when the last survey was published (PBS, 2020). According to The World Bank (2003), the vulnerable households of Baluchistan have widely benefited from improved learning and better healthcare facilities. With $36 million of funds, the Baluchistan Human Capital Investment Project has meaningfully improved the province’s human capital, which eventually translated into higher incomes over the last decade (World Bank Group, 2020). Moreover, Baluchistan is characterized by a primarily non-agricultural society. Most of the population is associated with the rising services sector or mining industry which saves them from the adverse effect of the suffering agricultural sector of the country (Huda et al. 2015; Kalim et al. 2018).

Variable of interest

Being an affiliate of orthodox deeni madrassas significantly positively impacts earned individual income (Table 3), even when interacting with the minority group variable (Table 4). Orthodox deeni madrassas are an embedded part of Pakistan’s educational and social ecosystem (Rahman, 2009; Tahir, 2022). One must realize that being an affiliate of a deeni madrassa has been one of the energized parts of social progress for the lower occupational strata and artisans in the rural population of Pakistan (Andrabi et al. 2005). Apart from the occupational background of their associates, after completing their academic tenure with the madrassa, they are sure to take a step forward to be part of the pecking order of social stratification, including income and social status (Ahmad, 2004).

Unlike other available educational options on the Pakistani scholastic canvas, the importance of deeni madrassas lies not only in their pedagogy of imparting religious education to a broad range of their learners but also ensures their immediate access to employment after graduation (Hamida et al. 2022). It has been noted that Pakistan has experienced extensive unemployment among the Generation Z educated in Westernized schools, colleges, and universities, as cited by Arslan and Zaman (2014), while the graduates of deeni madrassas have not encountered such issues and generally find employment that is in line with their education and training. Based on a survey conducted in 1979 of graduates of the two mainstream madrassas in Karachi and KPK, Ahmad (2004) reports that only 6% of the 1978 graduates were unemployed by the second quarter of 1979.

Furthermore, the drastic enlargement of the economy during the last decade has accommodated Ulema (clergy managing madrassas) to tap new and broader sources of income for their institutions. This diminished the shocks of economic crises on the religious establishments and mitigated their dependence on feudal lords, which were earlier the only source of funds for them (Ahmad, 2004). The new financing fraternity comprises market merchants, SME businesses, commission agents, wholesalers, and extensive business groups (Chandran, 2003). Therefore, this bureaucratization of orthodox Islamic institutions, including the restructuring and expansion of its financial net base by bringing the business community into their management structures, was later found to be an effective means for providing employment opportunities to the madrassa associates and ensuring lower unemployment in their social spectrum (Shafiq et al. 2019).

Additionally, as per PBS (2020), 96% of the population in Pakistan are Muslims, and the mainstream source of funding for deeni madrassas is Zakat (obligatory charity), Waqf, and Sadaqat (optional charity) (Rabbi and Habib, 2019). Therefore, this equation ensures an uninterrupted supply of funds to support the madrassa ecosystem. Communities pay charities (obligatory and optional), which the administration uses efficiently in supporting their needful associates and helping them by raising income-generating opportunities (Rahman, 2009). Since this funding source is tied to sacred responsibility, it ensures an unhindered flow of these cycles and thereby boosts the incomes of madrassa associates. Therefore, in light of the empirical findings, H1 is accepted.

The regression results for the extended equation show a similar significant positive impact of religious education on income as the baseline equation. The results denote the deeni madrassa affiliates from the minority pockets (Pashtun, Sindhi, Balochi, Saraiki, Kashmiri, and Muhajir) of the country earn more than their majority counterparts (Punjabis). The ethnic minority compartments of the country are home to mainstream business centers, such as Karachi, the nation’s economic capital (Hasan and Mohib, 2003). While the Punjabi populated areas are not business-intensive units, most of the population is related to agriculture-related employment (Farooq et al. 1999). The mainstream funds channeled to the madrassas are from feudal lords who in no way compete with the opportunities and infrastructure provided by the country’s business centers (Ahmad, 2004). At the same time, these minority localities are home to a more organized network of deeni madrassas compared to the sections where most Punjabis are located. Karachi and KPK are home to all the big orthodox Islamic institutions that came into existence just after the nation’s birth. A few notable institutions are Darul–Uloom Karachi, Jamiyah Binoria, Darul–Uloom Haqqania, and Jamia Farooqiyah (Ahmad, 2004 & Rahman, 2009). Hence, this nexus of rich business vicinities and well-organized madrassa networks results in more employment and income opportunities for madrasa affiliates. Accordingly, the empirical findings support the acceptance of H2.

Conclusion

This paper emphasizes estimating the impact of religiosity on individual income using sizeable microdata for the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The affiliation with orthodox Islamic institutions called “deeni madrasas” in the Muslim World signifies religiosity in this study. We are unaware of any study that scrutinizes the studied dilemma using the affiliation of deeni madrassa as a proxy for religiosity. The study formulates a basic and extended equation that interacts with the independent focus variable (RELEDU) with MINORITY. The results of both baseline and extended equations indicate a significant positive impact of religiosity on individual income during the study cohorts. The results of the estimations advocate the critical standing of deeni madrassas on the social and economic canvas of Pakistan, a strategically crucial Muslim nation globally. The developed ecosystem of these orthodox Islamic institutions, along with their affiliates, has been able to absorb the vulnerable economic shocks the country has experienced in the last decade, whether it was unemployment, floods, defaults, pandemics, and political instability. As the other sections of society struggle to keep pace with the rising inflation rate, the affiliates of madrassas maintain a stable growth trajectory with the solid financial and social support this ecosystem provides.

The findings presented in this paper significantly contribute to the literature examining the relationship between religion and economics. This paper contextually analyzes an average established Muslim country, Pakistan. Therefore, discussing the highest and lowest per capita income in Muslim countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Somalia, Niger, and Afghanistan, respectively, represents an exciting area for researchers to consider in the future.

The practical implications of this study are significant for policymakers, educators, and employers in Pakistan and beyond. The findings suggest that promoting access to orthodox Islamic education through religious institutions could be a viable strategy to positively impact individual incomes. Policymakers may consider incorporating religious education into educational policies, while employers and workforce development agencies might recognize its value in hiring and skill development. Additionally, the study highlights the positive influence of minority engagement with orthodox religious institutions on income, emphasizing the importance of social integration. This implies a need for culturally sensitive approaches in development programs and a reevaluation of the role of religious education in workforce dynamics. Individuals, too, might consider investing in orthodox religious education, as the study indicates potential economic benefits. Overall, the practical implications advocate for a nuanced understanding of the relationship between religiosity, education, and income, guiding the development of effective policies and strategies that align with the cultural context.

Data availability

The data for this study can be obtained from the Pakistan Social and Living Standard Survey (PSLM) conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS): https://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/pakistan-social-and-living-standards-measurement.

Notes

In this investigation, we posit the assumption that individuals possessing a foundation in orthodox religious education demonstrate, on average, heightened levels of religiosity in contrast to their counterparts with alternative educational backgrounds. The assessment of religiosity within a census population presents inherent complexities. Preceding empirical inquiries, including those by Buser (2015) and Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2005), have utilized church membership as a metric to gauge religiosity. It is noteworthy that our observation aligns the communal role of orthodox Islamic institutions with that of churches.

References

Abbasi MS, Tarhini A, Elyas T, Shah F (2015) Impact of individualism and collectivism over the individual’s technology acceptance behaviour. J Enterp Inf Manag 28(6):747–768. https://doi.org/10.1108/jeim-12-2014-0124

Afzal A, Mirza N, Arshad F (2020) Pakistan’s poverty puzzle: role of foreign aid, democracy & media. Econ Res-Ekonom Istraživanja 34(1):368–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677x.2020.1788964

Ahmad M (2004) Madrassa education in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) Research Hub. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.cve-kenya.org/cve-library/c1713c2e-c801-4464-9bbc-e0db41b69ae9

Ahmed V, Javed A (2016) National study on agriculture investment in Pakistan. © Sustainable Development Policy Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/11540/6822

Akhtar R, Liu H, Ali A (2017) Influencing factors of poverty in Pakistan: time series analysis. Int J Econ Financ Issues 7(2):215–222. https://econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/article/view/3349

Andrabi T, Das J, Khwaja AI, Zajonc T (2005) Religious school enrollment in Pakistan: a look at the data. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.667843

Arslan M, Zaman, R (2014). Unemployment and its determinants: a study of Pakistan economy (1999-2010). SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2515075

Awan M, Hussain Z (2007) Returns to education and gender differentials in wages in Pakistan. Lahore J Econ 12(2):49–68. https://doi.org/10.35536/lje.2007.v12.i2.a3

Azzi C, Ehrenberg R (1975) Household allocation of time and church attendance. J Polit Econ 83(1):27–56. https://doi.org/10.1086/260305

Barro RJ, McCleary RM (2003) Religion and economic growth across countries. Am Sociol Rev 68(5):760. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519761

Bartkowski JP (2014) Faith and money: how religious belief contributes to wealth and poverty. Contemp Sociol A J Rev 43(5):702–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306114545742dd

Becerra M, Santaló J, Silva R (2013) Being better vs. being different: differentiation, competition, and pricing strategies in the Spanish Hotel Industry. Tour Manag 34:71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.03.014

Beck SV, Gundersen SJ (2016) A gospel of prosperity? an analysis of the relationship between religion and earned income in Ghana, the most religious country in the world*. J Sci Study Relig 55(1):105–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12247

Bettendorf LJH, Dijkgraaf E (2005) The bicausal relation between religion and income. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.856004

Bettendorf L, Dijkgraaf E (2009) The bicausal relation between religion and income. Appl Econ 43(11):1351–1363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840802600442

Blanchard CM Islamic religious schools, madrasas: Background (2008). Washington, D.C.; Congressional Information Service, Library of Congress

Brañas-Garza P, Neuman S (2004) Analyzing religiosity within an economic framework: the case of Spanish Catholics. Rev Econ Househ 2(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:reho.0000018020.84844.7c

Brown MS (2000) Religion and economic activity in the South Asian population. Ethn Racial Stud 23(6):1035–1061. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198700750018405

Buser T (2015) The effect of income on religiousness. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 7(3):178–195. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140162

Campos B, Ren Y, Petrick M (2016) The impact of education on income inequality between ethnic minorities and Han in China. China Econ Rev 41:253–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.10.007

Chandio AA, Jiang Y, Magsi H (2018) Climate change impact on rice production in Pakistan: an ARDL-bounds testing approach to cointegration. Pak J Agric Agric Eng Vet Sci 34(1):79–88. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201812.0095.v1

Chandran S (2003) Madrassas in Pakistan. IPCS issue brief. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/138010/IB11-SubaChandran-MadrassasInPak.pdf

Cheema AR, Sial MH (2012) Poverty, income inequality, and growth in Pakistan: a pooled regression analysis. Lahore J Econ 17(2):137–157. https://doi.org/10.35536/lje.2012.v17.i2.a6

Chen DL (2010) Club goods and group identity: evidence from Islamic resurgence during the Indonesian financial crisis. J Political Econ 118(2):300–354. https://doi.org/10.1086/652462

Chetty R, Hendren N, Kline P, Saez E (2014) Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Q J Econ 129:623–1553. https://doi.org/10.3386/w19843

Chiswick BR (1983) The earnings and human capital of American Jews. J Hum Resour 18(3):313. https://doi.org/10.2307/145204

Cockcroft A, Andersson N, Milne D, Omer K, Ansari N, Khan A, Chaudhry UU (2009) Challenging the myths about Madaris in Pakistan: a national household survey of enrolment and reasons for choosing religious schools. Int J Educ Dev 29(4):342–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.09.017

Dehejia R, DeLeire T, Luttmer EFP (2007) Insuring consumption and happiness through religious organizations. J Public Econ 91(1-2):259–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.05.004

Ellison CG (1991) Religious involvement and subjective well-being. J Health Soc Behav 32(1):80. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136801

Evans TD, Cullen FT, Dunaway RG, Burton VS (1995) Religion and crime reexamined: the impact of religion, secular controls, and social ecology on adult criminality*. Criminology 33(2):195–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1995.tb01176.x

Farooq U, Young T, Iqbal M (1999) An investigation into the farm households consumption patterns in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak Dev Rev 38(3):293–305. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41260173

Felt LF, Sinclair PR (1992) “Everyone does it”: unpaid work in a rural peripheral region. Work, Employ Soc 6(1):43–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23746673 Top of Form

Freeman M (2013) The priority of the other. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199759309.001.0001

Fruehwirth JC, Iyer S, Zhang A (2019) Religion and depression in adolescence. J Political Econ 127(3):1178–1209. https://doi.org/10.1086/701425

Glaeser EL, Sacerdote BI (2008) Education and religion. J Hum Cap 2(2):188–215. https://doi.org/10.1086/590413

Gruber JH (2005) Religious market structure, religious participation, and outcomes: is religion good for you? Adv Econ Anal Policy 5(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1538-0637.1454

Gruber J, Hungerman DM (2008) The church versus the mall: what happens when religion faces increased secular competition?* Q J Econ 123(2):831–862. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.831

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2003) People’s opium? religion and economic attitudes. J Monet Econ 50(1):225–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3932(02)00202-7

Hamida, Bashir S, Khan Y (2022) Mainstreaming Madaris in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: a socioeconomic perspective. Indian J Econ Bus 21(1):843–853. http://www.ashwinanokha.com/IJEB.php

Hasan A, Mohib M (2003) Urban Slums Reports: The case of Karachi, Pakistan (2003rd ed., Ser. Understanding Slums, pp. 1–32). The Bartlett Development Planning Unit. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-projects/Global_Report/pdfs/Karachi.pdf

Heath WC, Waters MS, Watson JK (1995) Religion and economic welfare: an empirical analysis of state per capita income. J Econ Behav Organ 27(1):129–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(94)00028-d

Huda SN, Burke F, Azam M (2015) Socio-economic disparities in Baluchistan, Pakistan—a multivariate analysis. Malays J Soc Space 7(4):38–50. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2706561 Available at:

Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, Ellison CG (1999) Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography 36(2):273–285

Hungerman DM (2014) The effect of education on religion: evidence from compulsory schooling laws. J Econ Behav Organ 104:52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2013.09.004

Iannaccone LR (1992) Religious markets and the economics of religion. Soc Compass 39(1):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/003776892039001012

Iannaccone LR (1998) Introduction to the Economics of Religion. J Econ Lit 36(3):1465–1495. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2564806

Kalim I, Naqvi SZ, Mubeen M (2018) Socio-economic disparities in Baluchistan: assessing structuraletiology. Glob Econ Rev III(I):134–154. https://doi.org/10.31703/ger.2018(iii-i).14

Keister LA, Sherkat, DE (2014) Religion and inequality in America: research and theory on Religion’s role in stratification. Cambridge University Press

Kemal AR (1994) Structural adjustment, employment, income distribution and poverty. Pak Dev Rev 33(4II):901–914. https://doi.org/10.30541/v33i4iipp.901-914

Khan, KH (2009) Unpaid family workers in Pakistan. Paper presented at the Global Forum on Gender Statistics, 26–28 January 2009, Accra, Ghana. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/Ghana_Jan2009/Doc45.pdf

Khan K, Idrees M (2014) Determinants of earnings: a district wise mapping of Pakistan. Forma J Economic Stud 10:1–16. https://doi.org/10.32368/fjes.20141001

Khan MT, Sasaki K (2003) Regional disparity in Pakistan’s economy: regional econometric analysis of causes and remedies. Interdiscip Inf Sci 9(2):293–308. https://doi.org/10.4036/iis.2003.293

Khan MZ, Rehman S, Rehman CA (2015) Education and income inequality in Pakistan. Manag Adm Sci Rev 4:134–145

Kruijk HD, Leeuwen MV (1985) Changes in poverty and income inequality in Pakistan during the 1970s. Pak Dev Rev 24(3-4):407–422. https://doi.org/10.30541/v24i3-4pp.407-422

Lehrer EL (1999) Religion as a determinant of educational attainment: an economic perspective. Soc Sci Res 28(4):358–379. https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1998.0642

Lim C, Putnam RD (2010) Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. Am Sociol Rev 75(6):914–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122410386686

Lin X (2019) Multiple pathways of transportation investment to promote economic growth in China: A structural equation modeling perspective. Transp Lett 12(7):471–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/19427867.2019.1635780

Lipford JW, Tollison RD (2003) Religious participation and income. J Econ Behav Organ 51(2):249–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-2681(02)00096-3

McCleary RM, Barro RJ (2006) Religion and economy. J Econ Perspect 20(2):49–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.20.2.49

Meredith NR (2012) Labor income and religiosity: evidence from survey data. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2027096

Montgomery, WM (1991) Muslim-Christian encounters: perceptions and misperceptions. Routledge

Nielsen F, Alderson AS (1995) Income inequality, development, and dualism: results from an unbalanced cross-national panel. Am Sociol Rev 60(5):674. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096317

PBS. (2020) Population by religion—PBS. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/tables/population/POPULATION%20BY%20RELIGION.pdf

Rabbi F, Habib S (2019) Discourse on madrassa education reform in Pakistan: challenges to state narrative and its implications. Res J Al Baṣīrah 8(1):1–18. https://numl.edu.pk/journals/subjects/156775385912-01-134-ENG-V8-1-19-Formatted.pdf

Rahman K (2009) Madrassas in Pakistan: role and emerging trends (2009th ed., Ser. Islam and Politics). JSTOR. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep10936.10.pdf

Rehman A, Cismas LM, Milin IA (2022) “The three evils”: Inflation, poverty and unemployment’s Shadow on economic progress—a novel exploration from the asymmetric technique. Sustainability 14(14):8642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148642

Shafiq M, Azad AR, Munir M (2019) Madrassas reforms in Pakistan: a critical appraisal of present strategies and future prospects. J Educ Res 22(2):152–168. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338918660_Madrassas_Reforms_in_Pakistan_A_Critical_Appraisal_of_Present_Strategies_and_Future_Prospects

Shahnaz L, Khalid U, Akhtar S (2008) Unpaid family workers: unravelling the mystery of falling unemployment. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.35950.51521

Shaw R, Gullifer J, Wood K (2016) Religion and spirituality: a qualitative study of older adults. Ageing Int 41:311–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-016-9245-7

Shehzad A (2011) The issue of ethnicity in Pakistan: historical background. J Pak Vis 12(2):124–164

Sheikh MK, Gillani AH (2023) Ethnic issues and National Integration in Pakistan: a review. Pak J Humanit Soc Sci 11(1):187–195. https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2023.1101.0341

Silveus N, Stoddard C (2020) Identifying the causal effect of income on religiosity using the earned income tax credit. J Econ Behav Organ 178:903–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.08.022

Syed A, Raza T, Bhatti TT, Eash NS (2022) Climate impacts on the agricultural sector of Pakistan: risks and solutions. Environ Chall 6:100433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100433

Tahir I (2022) Decolonizing madrassa reform in Pakistan. Curr Issues Comp Educ 24(1). https://doi.org/10.52214/cice.v24i1.8853

The World Bank. (2003, September 15). World Bank to Gear up Support to Baluchistan. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website00811/WEB/OTHER/C36D784A.HTM?OpenDocument

Ullah A, Mahmood N, Zeb A, Kächele H (2020) Factors determining farmers’ access to and sources of credit: evidence from the rain-fed zone of Pakistan. Agriculture 10(12):586. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10120586

World Bank Group. (2020, June 23). Baluchistan Human Capital Investment Project. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/loans-credits/2020/06/23/balochistan-human-capital-investment-project

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this study and share the responsibility for its content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Disli, M., Hamza, S.M. Orthodox Islamic institutions and individual income: evidence from Pakistan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 849 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03161-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03161-8