Abstract

Our research explores the effects of green entrepreneurial orientation, green human capital, and corporate environmental strategy on green supply chain integration in the context of Chinese manufacturing firms. Grounded in the resource-based view, this study asserts that these constructs are crucial as internal resources contribute to sustainable competitive advantage. This study employs a systematic random sampling approach for data collection, targeting senior managers across key industrial sectors in China, including renewable energy, waste management, and green construction. By surveying 316 Chinese manufacturing enterprises and utilizing the partial least squares structural equation modeling technique, this paper reveals significant direct relationships among green entrepreneurial orientation, green human capital, corporate environmental strategy, and green supply chain integration. Additionally, we identify corporate environmental strategy as a critical mediating factor among the associations. The research contributes to the resource-based view by illustrating the potential of environmentally focused resources in promoting green innovation and integration. Our findings also reveal the significant importance of corporate environmental strategies in establishing a connection between green entrepreneurial efforts, human capital, and supply chain practices. Moreover, the study offers crucial strategic insights for manufacturing organizations seeking to align their entrepreneurial initiatives effectively, investments in human capital, and environmental plans to improve sustainability in their supply chain operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the modern business landscape, the urgency of embracing sustainability to gain competitive advantage has escalated across industries (Rehman et al. 2022; Yan et al. 2022). Organizations increasingly recognize the profound significance of adopting environmentally conscious practices for ethical reasons and to achieve operational resilience in an ever-changing and fiercely competitive environment (Liu et al. 2018; Shen et al. 2021). Within this context, the concept of green entrepreneurial orientation (GEO) has emerged as a pivotal driving force. Green entrepreneurial orientation reflects an organization’s proactive inclination to identify and capitalize on green business opportunities, showcasing a commitment to ecological responsibility while pursuing innovation (Habib et al. 2021; Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011). This orientation is inherently intertwined with green human capital (GHC), which signifies employees’ collective knowledge, skills, and expertise on environmental concerns and sustainable practices (Hina et al. 2024; Ren et al. 2018). Amidst this backdrop, green supply chain integration (GSCI) has garnered considerable attention as a pivotal strategy to streamline sustainable practices across the supply chain (Mani et al. 2016; Sarkis et al. 2011). Green supply chain integration involves the seamless alignment of environmentally conscious principles among suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers, fostering the efficient flow of eco-friendly products while minimizing environmental impact (Zhu et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, the intricate interplay between green entrepreneurial orientation and human capital in influencing green supply chain integration necessitates a thorough exploration. The role of corporate environmental strategy in shaping the connection between green entrepreneurial orientation, human capital, and supply chain integration warrants detailed examination. The corporate environmental strategy (CES) encompasses an organization’s deliberate development and strategy implementation that infuses environmental considerations into its core operations (Kolk and Pinkse, 2007; Orsato, 2006). This strategic framework potentially mediates the relationship between green entrepreneurial orientation, green human capital, and supply chain integration, thereby influencing the degree to which environmentally responsible practices are integrated across the supply chain (Liu et al. 2018; Qi et al. 2010).

Despite the increasing awareness and emphasis on environmentally sustainable practices within organizations (Al-Swidi et al. 2024; Marzouk and El Ebrashi, 2024), there exists a notable research gap in understanding the intricate interplay between GEO, GHC, and GSCI, particularly in the context of the potential mediating role of firms’ environmental strategy (Wang et al. 2023). While previous studies have acknowledged the individual significance of GEO and GHC in driving sustainable initiatives (Feng et al. 2022), a crucial need remains to explore how their combined influence affects green supply chain integration comprehensively (Longoni and Cagliano, 2015; Ren et al. 2018). Given the changing nature of these practices based on the dynamicity of the concept, fusing green entrepreneurial orientation and human capital into GSCI could be one of the novel approaches to drive environmental sustainability. However, the likely interaction between these components should be nuanced, and therefore, the previous studies on their direct ramifications from the literature may not suffice. While Feng et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2023) have already contributed to the understanding of the role of individual factors in promoting sustainability, more profound knowledge of how the environmental strategy enables green supply chain integration is needed. This approach is consistent with the resource-based view framework, which holds that a strategic use of internal resources can lead to a significant competitive advantage (Wernerfelt, 1984). The integration of the “green” dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation and human capital, as well as the use of corporate environmental strategy as a strategic resource, from the RBV perspective, provides a fresh viewpoint on supply chain sustainability. Indeed, while the importance of sustainable practices that would enlace the whole supply chain has been recognized in prior research (Feng et al. 2022; Habib et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2023; Khan et al. 2022), there seems to be a gap in knowledge about which mechanisms prove to enhance green supply chain integration, especially the green dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation and human capital, internal resources, and the contribution of environmental strategy.

Consequently, the primary objective of this study is to bridge this research gap by unraveling the intricate dynamics between GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES. The existing literature highlights the strategic importance of integrating sustainable practices across the supply chain to achieve enhanced environmental performance (Dubey et al. 2015; Wong et al. 2018). However, the mechanisms through which green entrepreneurial orientation and human capital collectively contribute to green supply chain integration and how environmental strategy might influence or moderate these relationships remain relatively unexplored. This study aims to address these gaps by investigating how organizations can strategically leverage their entrepreneurial orientation and human capital to drive effective green supply chain integration while considering the mediating or moderating role of environmental strategy. In light of this context, this study aims to investigate the following research questions: (a) What is the impact of GEO and green human capital (GHC) on green supply chain integration (GSCI)? (b) What function does corporate environmental strategy (CES) serve in influencing the link among GEO, GHC, and GSCI? These questions provide the basis of our study and direct the subsequent objectives: to investigate the synergistic effects of GEO and GHC on GSCI, and to analyse how CES may mitigate or mediate these associations.

By exploring the potential interactions among these variables, this study aspires to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by shedding light on the intricate relationships that drive sustainable supply chain practices. The research objectives are poised to uncover insights that can aid organizations in formulating informed strategies for achieving comprehensive environmental sustainability. As the business landscape continues to evolve, understanding the combined impact of green entrepreneurial orientation, human capital, and environmental strategy on green supply chain integration becomes imperative for organizations seeking to navigate the complexities of sustainability. Through empirical analysis across diverse industries, this study will pave the way for a more nuanced understanding of how these factors collectively shape green supply chain practices, thereby contributing to the broader discourse on sustainable business practices.

This research marks a significant advancement in the realm of strategic management, particularly within the RBV framework. By delving into the intricate relationships among green entrepreneurial orientation, human capital, supply chain integration, and environmental strategy, this study contributes to the evolution of our understanding of how internal resources can be strategically leveraged to attain environmental sustainability goals (Chen et al. 2004; Hitt et al. 2019). It introduces a paradigm shift by exploring the ‘green’ facet of entrepreneurial orientation, thereby extending the boundaries of RBV to encompass the impact of sustainability orientation on supply chain integration dynamics (Wang et al. 2014). Additionally, by incorporating green human capital into this framework, the study bridges a theoretical gap and redefines the significance of an environmentally aware workforce within the context of RBV (Singh et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2013). This spotlight on the intricate interplay between human capital, sustainability principles, and supply chain operations adds depth to our understanding. Furthermore, identifying environmental strategy as a mediator in the relationships between GEO, GHC, and GSCI adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of strategic environmental management (Montabon et al. 2007). This study addresses gaps in previous theoretical frameworks and provides a holistic view of the synergistic dynamics among these variables, thereby enriching our comprehension of how organizations can strategically align their internal resources with environmental imperatives to gain a competitive edge. This research enhances the theoretical foundation by unraveling the intricate connections among GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES. Its framework draws from diverse theoretical viewpoints, contributing to the ongoing discussions on sustainable supply chain management. By shedding light on the pivotal role of a strategic approach to integrating green practices across supply chain operations, this study advances our understanding of sustainable business practices in a rapidly changing business landscape.

A subsequent framework has been devised for this paper to accomplish the research objectives. The second part provides a thorough literature assessment on GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES subjects. The paper’s third section offers a comprehensive overview of the research methodology employed in this study. It encompasses details pertaining to the gathering of data, the selection of the sample, and the utilization of analytical instruments. The fourth section presents the empirical analysis results according to the proposed hypotheses. The fifth section provides a complete analysis of the research findings, examining their ramifications and acknowledging the study’s limitations. The paper’s sixth section comprehensively assesses the research findings and offers recommendations for future scholars who wish to investigate novel directions within this field.

Theoretical background

Resource-Based View (RBV)

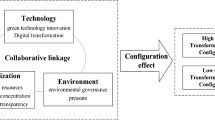

The resource-based view (RBV) has been a pivotal framework in strategic management literature, emphasizing an organization’s internal resources as the primary determinant of its competitive advantage and performance (Chen et al. 2004). Originating from the works of Barney and Wernerfelt, RBV posits that firms can achieve sustainable competitive advantage by leveraging unique, valuable, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources (Hitt et al. 2019). In environmental management, the RBV has been instrumental in understanding how firms can harness their internal resources to address environmental challenges and opportunities (Hart and Dowell, 2011). The proactive stance towards ecological management, rooted in RBV, posits that firms can transcend compliance with environmental regulations to carve a competitive niche (Wang et al. 2014). The integration of GEO and GHC within the RBV framework accentuates the significance of environmentally-centric entrepreneurial activities and the pivotal role of human capital in spearheading green initiatives (Zhu et al. 2013). Green entrepreneurial orientation underscores the firm’s inclination to pinpoint and capitalize on green market opportunities, while green human capital delves into the knowledge and skills of employees who are instrumental in rolling out green practices (Singh et al. 2019). The green supply chain integration paradigm, anchored in the RBV, underscores the essence of weaving in environmental considerations throughout the supply chain continuum, from suppliers to end consumers. This integration mandates firms to harness their internal resources, including green technological prowess and human capital, ensuring that the tenets of environmental sustainability are ingrained in every facet of the supply chain (Rao and Holt, 2005). Furthermore, the corporate environmental strategy is quintessential in steering firms’ environmental endeavors and decisions. Drawing insights from the RBV, a cogent environmental strategy can align a firm’s internal resources with ecological objectives, culminating in enhanced environmental performance and a competitive edge (Montabon et al. 2007). This research, therefore, leans on the RBV as its foundational theory to delve into the nexus between GEO, GHC, GSCI, and the potential mediating role of CES. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of our investigation.

Development of hypothesis

Green entrepreneurial orientation and firms’ green supply chain integration

Green entrepreneurial orientation (GEO) encapsulates a firm’s strategic commitment towards spotting and capitalizing on opportunities that endorse environmental sustainability, an approach that emphasizes innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking concerning green business activities (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011). It embraces an entrepreneurial mindset aimed at creating sustainable value for a company while contributing to improving the environment (Cohen and Winn, 2007). Drawing insights from the RBV, green entrepreneurial orientation can be viewed as a strategic resource that integrates corporate culture and a dynamic capability, helping firms identify, seize, and maintain environmental activities (Shehzad et al. 2023). Recent studies have found that green entrepreneurial orientation helps integrate and implement corporate environmental responsibilities (Ameer and Khan, 2022; Wang et al. 2023). It also supports green innovation in the firm’s supply chain (Tze San et al. 2022). Simultaneously, green supply chain integration (GSCI) involves adopting and implementing environmentally friendly practices across the supply chain processes, from sourcing raw materials to delivering finished products. This perspective underscores the importance of minimizing environmental impact through waste reduction, resource preservation, and curtailing emissions in the supply chain (Srivastava, 2007; Zhu et al. 2012).

Recent research has provided substantial evidence supporting the link between green entrepreneurial orientation and green supply chain integration. Habib et al. (2020) highlighted that firms with a robust GEO were more adept at integrating green initiatives within their supply chains, confirming a positive association between GEO and GSCI. Hall (2000) also explored the relationship between environmental orientation and a company’s ability to incorporate sustainable practices, finding that a solid entrepreneurial orientation towards the environment positively influenced GSCI. Elevated GEO can lead to more efficient GSCI implementation and superior sustainability performance (Centobelli et al. 2021). By fostering an entrepreneurial mindset towards sustainability, companies could identify and leverage green opportunities across their supply chains, leading to more effective integration of sustainable practices and improved sustainability performance. Furthermore, Guo et al. (2020) observed that GEO significantly predicted the extent to which firms implemented and managed GSCI. Companies with high GEO were likelier to have advanced green supply chains and achieve better environmental performance. GEO encouraged firms to continuously seek green opportunities and innovations, resulting in more comprehensive and effective GSCI. Likewise, Feng et al. (2022) found that strong GEO translated to more effective GSCI implementation and superior sustainable performance. Embedding an entrepreneurial mindset into sustainability allowed firms to identify and exploit green opportunities throughout their supply chains, enhancing the overall integration of sustainable practices and sustainability performance. Moreover, Ralston et al. (2015) provided evidence that GEO could improve the effectiveness of GSCI. Firms with a strong GEO were better at incorporating environmental considerations into their strategic decisions, leading to more successful GSCI and improved environmental performance.

However, the assumption that a strong GEO always positively influences GSCI might not hold in every context. While companies with a strong GEO may be more environmentally aware and proactive, they might not necessarily have the practical capabilities or resources to fully integrate green practices across their supply chain, indicating a complex and potentially non-positive relationship between GEO and GSCI (Majali et al. 2022). Furthermore, without the requisite organizational culture, resources, and infrastructure, firms may struggle to successfully integrate green practices into their supply chains, irrespective of their entrepreneurial orientation (Alfandi and Bataineh, 2023). Accordingly, we postulate:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Green entrepreneurial orientation positively influences firms’ green supply chain integration.

Green entrepreneurial orientation and firms’ corporate environmental strategy

Green entrepreneurial orientation involves a firm’s strategic approach to recognizing and exploiting opportunities that promote environmental sustainability (B. Cohen and Winn, 2007). It combines innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking in the context of green business practices, thereby fostering an entrepreneurial mindset that creates sustainable value for the company while simultaneously contributing to environmental betterment (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011). On the other hand, Corporate Environmental Strategy (CES) is the strategic alignment of a company’s operations with environmental sustainability objectives (Kolk and Pinkse, 2007). It integrates environmental considerations into strategic decision-making, business practices, and processes. Companies can reduce their environmental effect, meet and/or exceed legal standards, improve their reputation, and gain a competitive advantage in the market by implementing a CES (Orsato, 2006).

Recent studies have empirically investigated the relationship between GEO and CES. The study conducted by Alraja et al. (2022) unveiled a positive association between GEO and CES. This finding suggests that organizations with a higher level of GEO tend to exhibit more effectiveness in formulating and executing comprehensive environmental plans. A similar study by Ritala et al. (2021) examined the influence of GEO on CES in the context of technology firms. The study discovered that companies with a high level of GEO were more likely to develop and implement CES, supporting the positive correlation between GEO and CES. This was attributed to the increased propensity of these companies to innovate, take risks, and engage in green business practices proactively. Within the ___domain of corporate sustainability, the focus extends beyond the mere implementation of CES, encompassing the crucial aspect of the caliber of the adopted CES. Firms with a robust GEO were more likely to adopt a high-quality CES – that is, an environmental strategy that is comprehensive, proactive, and deeply ingrained in the firm’s operational processes (Habib et al. 2021). Firms with a strong GEO are more likely to develop comprehensive and proactive environmental strategies, demonstrating a positive correlation between GEO and CES (Muangmee et al. 2021). A firm’s green entrepreneurial mindset allows the managers to recognize green opportunities, effectively integrating them into their strategic planning and operations, thereby enriching the firm’s CES (Scarpellini et al. 2018). GEO does not only lead to the adoption of CES but also positively influences its implementation. A study by Singh et al. (2020) showed that GEO was linked with better implementation of CES. The study concluded that the proactive and innovative mindset associated with GEO enables the firm to execute CES better in its operations. Additionally, GEO has been observed to foster long-term commitment to CES. In a longitudinal study by Triguero et al. (2013), they found that firms with an intense GEO are not just more likely to adopt CES, but they are also more likely to sustain its implementation in the long term. Thus, it is conceivable that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Green entrepreneurial orientation positively influences firms’ environmental strategy.

Green human capital and firms’ green supply chain integration

Green human capital (GHC) encompasses employees’ eco-friendly knowledge, skills, and abilities. Recognized as a vital driver of environmental sustainability, GHC enables organizations to seamlessly restructure their operations with green initiatives (Marrucci et al. 2021). On the other hand, Green Supply Chain Integration (GSCI) incorporates ecological considerations throughout an organization’s supply chain, from raw material sourcing to waste management (Mani et al. 2016; Sarkis et al. 2011).

A strong correlation between GHC and the successful implementation of GSCI has been observed in multiple studies. For instance, Liu et al. (2013) highlighted that organizations fortified with GHC were adept at integrating environmental aspects within their supply chains. Such firms could efficiently operationalize their green knowledge into actionable strategies, fostering sustainable change. Furthermore, companies rich in GHC could embed eco-friendly principles, thereby enhancing GSCI (Longoni et al. 2014). Similarly, Shahid et al. (2020) deduced that a high GHC level within companies often equates to a more holistic green supply chain. This is attributed to the fact that GHC equips companies with the proficiency to comprehend and govern the environmental implications of their supply chain endeavors. This, in turn, eases the adoption of avant-garde green practices, amplifying environmental performance while promoting GSCI (Albort-Morant et al. 2018). Moreover, Al-Minhas et al. (2020) opined that GHC bolsters a firm’s capability to amalgamate green methodologies in their supply chains, invariably leading to an upswing in environmental performance. Another dimension to the merits of GHC is its role as a catalyst for green innovation. Firms endowed with substantial GHC can pioneer innovative green methodologies, thereby boosting their sustainability (Wang et al. 2022). The comprehensive value of GHC lies in its potential to enhance green innovation while also synchronizing supply chain processes with overarching environmental goals (Aftab et al. 2022).

However, it is imperative to note that the relationship between GHC and GSCI is not unanimously positive. Bhardwaj (2016) cautioned that while GHC can elevate environmental awareness, it does not unequivocally promise the actual integration of these practices. Management backing, innovative green technologies, and firm-wide eco-policies might play a more dominant role in advancing GSCI (Dubey et al. 2015). Additionally, the influence of GHC on GSCI might vary based on the industry, as certain sectors might not view green initiatives as a pivotal competency (Jabbour and De Sousa Jabbour, 2016). There’s also a risk of over-focusing on GHC, which might inadvertently eclipse other critical areas like technology and infrastructure, potentially hindering green supply chain integration (Longoni et al. 2018). Therefore, we can speculate that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Green Human Capital positively affects firms’ green supply chain integration.

Green human capital and firms’ corporate environmental strategy

GHC, comprising employees’ skills, knowledge, and abilities in implementing environmentally friendly practices, is vital in encouraging eco-innovation and fostering environmental awareness within a company (Singh et al. 2020). On the other hand, corporate environmental strategy incorporates sustainable and environmentally friendly practices into business operations and policies (Yu et al. 2020). It symbolizes the intention of a company to align its operations with the principles of environmental sustainability. In this respect, employees who understand the environmental implications of their actions can contribute substantially to creating and supporting the development of the firm’s environmental strategies.

Scholars have increasingly focused on exploring the interplay between GHC and CES in recent years. Bhardwaj (2016) conducted a study that established a positive correlation between GHC and the adoption of CES. They asserted that the competencies, skills, and attitudes embedded in GHC serve as enablers for comprehending and enacting green strategies within companies. Notably, firms with a pronounced emphasis on GHC exhibited enhanced resource efficiency and waste reduction, thus contributing substantively to a robust CES. The higher the level of GHC, the more successful the firm was at integrating environmental sustainability into its business strategy (Hameed et al. 2022). Furthermore, Mondal and Samaddar (2023) augmented this perspective by highlighting the significant impact of GHC on CES. Their research uncovered that companies with elevated levels of GHC tend to cultivate more robust CES. These firms, equipped with requisite knowledge and skills, recognize the potential benefits of environmental sustainability and seamlessly weave these considerations into their corporate strategies. This acumen favors them in navigating regulatory shifts and environmental challenges (Munawar et al. 2022). Employees armed with green competencies effectively guide their companies through the intricate regulatory landscape, enabling proactive alignment of operations with ecological mandates, a cornerstone of CES. Recent findings by Trujillo-Gallego et al. (2022) echoed and reinforced these insights, illuminating the pivotal role played by GHC in shaping CES. Their study underscored that businesses leveraging employees with eco-centric knowledge and skills demonstrated an inclination towards formulating and executing green strategies, leading to enhanced environmental performance and competitive edge. Notably, GHC’s influence extends to the realm of stakeholder relations. Companies endowed with higher levels of GHC exhibited superior adeptness in managing relationships with stakeholders encompassing customers, suppliers, and regulatory bodies. This facet is of paramount significance, given that effective stakeholder management stands as a linchpin in the successful realization of a comprehensive CES (Tang et al. 2018). Thus, we can formulate:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Green human capital positively affects firms’ environmental strategy.

Corporate environmental strategy and firms’ green supply chain integration

Environmental strategy can be defined as an organization’s strategic orientation toward identifying, understanding, and managing environmental issues related to its operations and activities (Albertini, 2013). Corporate environmental strategy involves making decisions and creating policies that reflect a commitment to reducing the environmental impact of a firm’s operations, products, and services (Orsato, 2006; Wang and Sarkis, 2017). Such a strategy aims to synergize business operations with ecological sustainability, thereby delivering both economic and environmental benefits (Hartmann and Moeller, 2014). Green supply chain integration, on the other hand, represents the implementation of environmentally friendly practices and principles across the entire supply chain (Ahi and Searcy, 2013; Chen et al. 2006). Green supply chain integration involves reducing waste, improving resource efficiency, and minimizing the environmental impact of supply chain activities, from sourcing and production to distribution and disposal.

Numerous empirical studies have delved into the intricate relationship between firms’ environmental strategy and green supply chain integration. A noteworthy example is the work of Qi et al. (2010), whose findings underscore the substantial impact of a robust environmental strategy on supply chain integration. Their research revealed that companies entrenched in well-established environmental strategies tend to embrace eco-friendly practices within their supply chains. This adoption, in turn, translates into amplified environmental performance and an elevated competitive advantage. Notably, the capacity of firms with a strong environmental strategy to adeptly discern and manage environmental risks along their supply chains plays a pivotal role in promoting green supply chain integration (Liu et al. 2018). Firms that embed environmental strategies into their core business strategies are more likely to innovate in their supply chain processes. This innovation often leads to supply chain integration, demonstrating efficiency and sustainability gains that enhance firm competitiveness (Witjes and Lozano, 2016). Testa et al. (2012) contribute to this discourse by proposing that a thoughtfully formulated environmental strategy can act as an impetus for green supply chain integration. Their study indicated that implementing environmental strategies correlates with superior environmental risk management, leading to an augmented green supply chain integration. This correlation is especially pronounced when firms deploy green procurement practices, efficient waste management strategies, and energy-conscious logistics. Furthermore, active engagement in CES appears to catalyze the seamless integration of green practices within supply chains (Dubey et al. 2015). These companies, adept at implementing green initiatives across all supply chain stages, tend to witness waste reduction, heightened resource efficiency, and overall improved environmental performance. Reinforcing the profound impact of CES-GSCI alignment, Wong et al. (2018) demonstrated that organizations strategically harmonizing their CES and GSCI endeavors reap superior financial outcomes and commendable environmental performance. This empirical support firmly underscores the positive nexus between firms’ environmental strategies and green supply chain integration. However, it’s noteworthy that the effectiveness of CES’s influence on GSCI could vary contingent on factors like company size, industry sector, and regulatory milieu. Yet, amidst these variables, a prevailing consensus in the scholarly discourse suggests that a robust environmental strategy bears the potential to exert a positive influence on firms’ pursuit of green supply chain integration. In light of these insights, it’s reasonable to posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Corporate environmental strategy positively affects firms’ green supply chain integration.

Mediating role of corporate environmental strategy

In today’s evolving business landscape, firms increasingly recognize the importance of green entrepreneurial orientation (GEO). This orientation underscores a company’s commitment to identifying and capitalizing on opportunities championing environmental sustainability, pushing them to innovate and proactively address environmental challenges (Brandenburg and Rebs, 2015; Montabon et al. 2016). GEO provides a strategic lens through which organizations envision a sustainable future. However, the empirical relationship between green and green supply chain integration is not always linear or directly positive. While some research suggests that a strong GEO often aligns with advanced GSCI practices (Criado-Gomis et al. 2017), other findings indicate that this alignment might be obfuscated by various factors like operational limitations, industry norms, and immediate business goals (Adomako et al. 2021). A discernible gap exists between possessing a green entrepreneurial mindset and its tangible manifestation in supply chain practices. Corporate environmental strategy emerges as a potential linchpin in bridging the relationship between a firm’s GEO and GSCI. While GEO represents the ideational drive, setting a green vision and intent for companies, the CES dictates how these intentions are pragmatically brought to life (Cherrafi et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2016). Without a comprehensive CES in place, the aspirations engendered by GEO may remain unmanifested in GSCI initiatives. CES is pivotal in how firms navigate their supply chains, emphasizing eco-friendly vendor associations, championing sustainable logistics, and endorsing efficient waste reduction strategies (Zhu et al. 2012). It frames the discourse on sustainability within corporate structures, influencing nuanced decisions around sustainable procurement and vendor collaborations, ensuring that green entrepreneurial spirit transforms into tangible, actionable steps (Ge et al. 2018). Furthermore, CES’s influence becomes even more evident when examining the discrepancies in research findings on the GEO-GSCI relationship. A well-constructed CES can channel the ambitions of GEO seamlessly into GSCI endeavors, leading to successful green integration. In contrast, in the absence of a robust CES, firms, despite their green entrepreneurial inclinations, may grapple with aligning their GEO with GSCI, resulting in varied empirical outcomes (Dangelico, 2016; Dangelico and Pontrandolfo, 2015).

Similarly, as noted by scholars and researchers, the intricate interplay between GHC and GSCI underscores the importance of environmental expertise, training, and awareness that GHC imparts (Awwad Al-Shammari et al. 2022; Kuo et al. 2022). This green human capital can act as an adaptive advantage, allowing firms to swiftly respond to the sustainability challenges of the modern business landscape. Such expertise often engenders a higher level of employee engagement with green initiatives, which, in theory, could directly translate to robust GSCI practices (Choi and Hwang, 2015). However, the bridge between possessing GHC and actualizing GSCI is not always straightforward. For instance, operational inertia stemming from legacy systems, inter-departmental misalignment, and resistance to change can serve as significant hurdles (Paulraj, 2011). Additionally, even firms flush with GHC might falter in achieving GSCI if external stakeholders, like suppliers, do not share a complementary commitment to green initiatives (Sundram et al. 2018). The presence of contrasting findings suggests the role of intermediary factors in shaping the GHC-GSCI relationship. CES embodies a firm’s commitment to integrating environmental considerations into its strategic objectives and emerges as a promising mediator (Hartmann and Moeller, 2014). While GHC provides the necessary capabilities, CES ensures the effective deployment of these skills to streamline and enhance green practices within supply chains (David et al. 2017). A robust CES serves as a catalyst for improving top management commitment, thereby nurturing an organizational culture that prioritizes and underscores the significance of GSCI. Through its presence, CES unlocks the full potential in GHC (David et al. 2017). Furthermore, CES’s role extends beyond mere facilitation; it furnishes an illuminating framework that explicates the disparate findings across research. To illustrate, the absence of a comprehensive CES amidst firms possessing substantial GHC can illuminate the challenges experienced in realizing GSCI, thus shedding light on the negative or non-significant relationships, as evidenced by Lee (2015). In light of these findings, it can be posited that:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Corporate environmental strategy mediates the relationship between GEO and green supply chain integration.

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Corporate environmental strategy mediates the relationship between GHC and green supply chain integration.

Research methods

Data collection and sample

This study collected data from manufacturing firms located in three economically and industrially significant provinces in China: Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. These provinces were chosen due to their leading roles in China’s green manufacturing movement and their diverse mix of industries relevant to our study’s focus on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investment portfolio sectors. Our study population encompasses manufacturing firms that are either already engaging in or have the potential to integrate green procedures and implement them in their business operations. More specifically, manufacturing firms involved in renewable energy, recycling, the environmentally friendly consumer goods sector, organic agriculture, and green construction were considered as our population. These particular sectors have been chosen owing to their correlation with China’s Environmental, Social, and Governance investment line and their relevance to sustainable economic development. The industries selected include renewable energy, waste management, eco-friendly consumer goods, organic farming, and green construction. With the firms operating in a rapidly expanding market, demanding consistent progress and innovation, the growing green industry in China is becoming crucial for sustainable economic development.

Our target audience was comprised of senior managers and sustainability officers who are pivotal in shaping and implementing green policies within their firms. These individuals possess the expertise, influence, and firsthand experience to provide in-depth insights into the relationship between GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES in their respective organizations. A self-administered survey was formed to collect data about the influence of GEO, GHC, and GSCI on CES. After the initial formation, minor adjustments were made based on the feedback from a primary test group consisting of academic researchers and business management professionals. The final questionnaire was distributed among 480 firms along with a letter describing the research goal and emphasizing that the company’s participation is voluntary. The sample was chosen and obtained using a systematic sampling technique, guaranteeing a fair depiction of the chosen fields. Moreover, an established sample frame with distinct criteria for selection made it possible to include firms making considerable efforts toward ESG objectives. Ethical considerations were paramount throughout the survey process. Participants received affirmation regarding the utmost confidentiality of their responses and their exclusive purpose for academic research. A further reminder helped receive 316 complete and credible surveys, making the response rate 72%. The sample size of 316 respondents from different manufacturing sectors is adequate for running the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis. PLS-SEM is known to be a type of multivariate analysis that can ensure a relatively reliable and accurate result even with small-to-medium sample sizes. According to Hair et al. (2016), PLS-SEM can provide reliable results with small to medium sample sizes, making it particularly suitable for complex model testing in business research. Our sample size exceeds the recommended minimum of 10 times the maximum number of structural paths directed at a particular construct in the model (Hair et al. 2021). This study employs cross-sectional data to examine the relationships among the constructs of interest, capturing a snapshot of the variables and their interactions within a defined period. The data collection took place between April and June 2023.

Survey instrument development

Several questionnaire items influenced by prior research were utilized to evaluate the study’s hypotheses. Some items underwent revisions to comply with the present investigation. A seven-point Likert scale was used to evaluate the exogenous variables. Prior to the primary data collection, the survey instrument was generated in agreement with the suggestions of Tjahjadi et al. (2022) and Feng et al. (2022). The study’s questionnaire items were distributed among a panel of six academic experts and seven industry practitioners. Their objective was to determine the precision of these items that reflected the intended concepts. The items were rated using a 3-point Likert scale, with “3” specifying a high degree, “2” specifying a moderate degree, and “1” specifying no degree. The survey instrument only included items that received a “3” rating from at least two experts and were not rated as “1” by any of them. This scale was selected because it is simple and effective enough to measure the expert consensus on item relevance, thus providing better discrimination of expert evaluations. The measurement items used in this research were sourced from existing literature sources. Prior research by Jiang et al. (2018) was used to determine the GEO of companies using five items. These metrics determined whether the firms utilize their green entrepreneurial capabilities to improve operational efficiency. Five items from Agyabeng-Mensah and Tang (2021) were used to calculate the green human capital of the companies. The utilized metrics investigated how a company’s GHC impacts the integration and performance of its green supply chain. We adopted three items from Tan et al. (2022) to measure the ENS construct. Finally, from the study of Han and Huo (2020), nine items were used to evaluate the GSCI construct (Table 1). Ultimately, the questionnaire consisted of structured Part A – demographic and organization profile questions, and Part B, which includes closed-ended study-specific items assessing GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES.

Data analysis techniques

This study used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the hypotheses. PLS-SEM was selected due to its suitability in evaluating complex connections between variables and its ability to generate valid findings with small sample sizes. (Afum et al. 2023; J. F. Hair et al. 2011). A variant of structural equation modeling (SEM), PLS-SEM analyzes statistical models, emphasizing causal explanations and prediction (Pratono et al. 2019). SmartPLS Version 4.0 was utilized for the analysis, and the formation of the model highlighted a causal viewpoint (Wagner et al. 2018). Five thousand subsamples and the bootstrap method were used to test the hypotheses. Measurement and structural models were constructed using structural equation modeling. While the structural model investigated the connections between these underlying constructs, the measurement model focused on identifying the connections between observed variables and these underlying constructs (Siddik, Yong, et al. 2023). The dependability of the structural model was evaluated using the convergent and divergent validity criteria (Al-Hakimi et al. 2021). The study performed statistical analysis to investigate the potential common method bias (CMB) using the single-factor testing method of Harman, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003). All exploratory factors underwent an analysis, and a single factor that explained 41.75% of the total variance specified no substantial method bias as it falls below the 50% threshold. In addition to these statistical procedures, several procedural strategies were applied to reduce CMB. They include respondent anonymity, the time separation between the predictor and criterion variable measurement, and an assurance that respondents answered honestly without any “right” and “wrongs. Since the statistical analysis identified no significant method bias, all these procedures support the study’s methodology. The study findings are presented in detail below.

Findings

Measurement Model

We examined the measurement model to evaluate the reliability and validity of the constructs included in the research model. These constructs include green entrepreneurial orientation, green human capital, corporate environmental strategy, and green supply chain integration. The assessment encompassed an investigation of the factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha values.

The results indicate that the factor loadings for each component of the factors GEO, GHC, CES, and GSCI surpassed the minimum criterion of 6 (Hair Jr. et al. 2016), proving each item’s reliability (Table 2). The robust alignment suggests that each item effectively assesses the intended concept. Reliability was assessed by employing two measures: CR and Cronbach’s Alpha. The CR values for all variables exceeded the suggested threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al. 2019). The individual alpha values for GEO, GHC, CES, and GSCI were 0.843, 0.762, 0.813, and 0.834, respectively. As Hair et al. (2016) outlined, the concept of reliability presupposition was validated by the observation that the Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values for each construct exceeded the threshold of 0.70. This indicates that the components within each construct demonstrated internal consistency (Huang et al. 2023).

The current study has successfully established the measurement instrument’s construct validity (CV). The average variance extracted (AVE) values for the constructs varied between 0.574 and 0.829, exceeding the threshold of 0.5 suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). This indicates that the variables have satisfactory convergent validity. The observation mentioned above was supported by the considerable and statistically significant standardized loadings of each item inside the model on its respective construct (Siddik, Rahman, et al. 2023).

The assessment of discriminant validity (DV) was conducted by applying two criteria: the Fornell and Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT) criterion, as specified by Hair et al. (2019). The correlation matrix among the latent variables displayed diagonal values greater than those below the diagonal, indicating the presence of discriminant validity (Table 3). Furthermore, the HTMT values were observed to be below the established threshold of 0.90, suggesting discriminant validity and verifying that the variables are statistically separate (Hair et al. 2019; Henseler et al. 2015).

The factor loadings, AVE, CR, Cronbach’s Alpha, and the findings on convergent validity and discriminant validity collectively provide strong evidence in favor of the measurement model’s reliability and validity.

Structural model

The structural model evaluation was rigorously carried out to comprehend the interrelationships between the GEO, GHC, CES, and GSCI constructs. The statistical significance of the links between these latent components was determined using the bootstrapping method, which involved generating 5000 subsamples (Chin et al. 2008).

The R² values are important indicators used to assess the extent to which the variance in the endogenous variables is explained. Table 4 presents the R² values above the minimum requirement of 0.1. The R² value for CES is 0.50, indicating substantial explanatory power. Similarly, the R² value for GSCI is 0.573, further suggesting significant explanatory power. The robust observation is additionally supported by the Q² metric, which highlights the predictive significance of the endogenous factors. Given that all Q² values are greater than zero, the present analysis unequivocally supports the predictive relevance of the variables under investigation (Table 4). Moreover, the f2 values suggest that green entrepreneurial orientation and green human capital have a medium effect on green supply chain integration (Cohen, 1988).

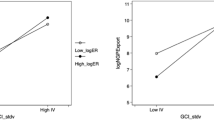

Our findings validate the association between GEO and GSCI, hence supporting H1, which suggests that GEO has a beneficial impact on integrating enterprises’ green supply chains at a 1% significance level. The linkage mentioned above is additionally expanded upon in the context of the CES, hence offering support for H2, which posits that GEO has a significant impact on CES. Further, our findings reveal that GHC has a favorable effect on CES (β = 0.498, t = 11.458, p = .000) and GSCI (β = 0.367, t = 6.908, p = 0.000) at a 1% significance level. Thus, hypotheses 3 and 4 are also supported, thereby illustrating the positive impact of green human capital on both corporate environmental strategy and supply chain integration (see Table 5).

The subsequent analysis demonstrates that the impact of CES on GSCI supports Hypothesis 5 (H5), suggesting that implementing corporate environmental strategy has a positive influence on integrating green supply chains inside enterprises (Table 5). The mediation analysis provides strong support for the involvement of CES in the interactions between GEO and GSCI, as well as between GHC and GSCI. The mentioned mediation roles are consistent with Hypothesis 6 (H6) and Hypothesis 7 (H7), suggesting that the company’s environmental strategy is crucial as a mediator (Fig. 2).

To conclude, the findings of the structural model provide extensive and significant insights into the interplay between GEO, GHC, CES, and GSCI. The model reveals positive associations and intricate mediation effects among the dimensions. Our findings highlight the significance of firms’ environmental strategies in facilitating the linkages between entrepreneurial orientation, human capital, and supply chain integration. This finding offers novel insights into the intricate interrelationships within the field of green management, thereby making valuable contributions to both theoretical comprehension and practical implementation.

Discussions

The purpose of this study was to understand the intricate dynamics between GEO, GHC, GSCI, and the mediating role of CES. The findings from this study, in conjunction with the extensive literature review, offer several noteworthy insights. The first hypothesis proposed a positive influence of a firm’s GEO on its GSCI. This relationship has garnered significant attention in recent research, underscoring its profound implications. The findings from the SEM analysis provide substantial support for Hypothesis 1 by confirming a favorable connection between GEO and GSCI. Central to the concept of GEO is a firm’s strategic dedication to environmental sustainability (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011). This commitment extends beyond passive acknowledgment, actively pursuing opportunities that endorse and champion green practices. Notably, firms exhibiting a robust GEO exhibit heightened proficiency in seamlessly integrating green initiatives within their supply chains. This alignment echoes the foundational principles of GEO, which assert that a proactive and innovative approach to environmental sustainability propels companies to adopt and effectively implement green practices across their supply chains (Habib et al. 2020). Companies that proactively embrace innovative approaches to environmental sustainability inherently possess a more favorable position to align their supply chains with green principles (Hall, 2000). This alignment, in turn, culminates in an enhanced sustainability performance. Higher levels of GEO correlate with more streamlined implementation of green supply chain practices, leading to improved sustainability outcomes (Centobelli et al. 2021). However, it is crucial to recognize that the landscape of the GEO-GSCI relationship is nuanced and not uniformly positive. While companies with a robust GEO inherently display improved environmental awareness and proactivity, practical challenges may hinder the complete integration of green practices throughout their supply chains (Majali et al. 2022). The vision and intent embedded within GEO are vital, yet the realization of this vision in the form of comprehensive GSCI hinges upon a multifaceted interplay of factors. Organizational capabilities, availability of resources, and external contextual conditions collectively determine how much a firm can translate its green entrepreneurial orientation into tangible and practical actions within its supply chain. The successful translation of GEO into GSCI necessitates the existence of a supportive infrastructure, adequate resources, and a conducive organizational culture (Alfandi and Bataineh, 2023). Without these essential elements, companies driven by a solid green entrepreneurial orientation may encounter challenges in seamlessly integrating green practices throughout their supply chains.

Hypothesis 2 posits that GEO positively affects CES. The positive correlation between these constructs is in line with the existing literature. CES represents the strategic alignment of a company’s operations with environmental sustainability objectives (Kolk and Pinkse, 2007; Orsato, 2009). The blueprint dictates how a firm’s green entrepreneurial aspirations are translated into actionable steps. Therefore, the relationship between GEO and CES is not just one of correlation but of causation. Firms with a pronounced GEO are more inclined to develop a CES and depend on it to realize their green entrepreneurial ambitions. Organizations with a higher level of GEO tend to exhibit more effectiveness in formulating and executing comprehensive environmental plans. This finding is consistent with the notion that an entrepreneurial mindset toward ecological sustainability can drive firms to integrate these principles into their corporate strategies (Alraja et al. 2022). Companies with a high level of GEO were more likely to develop and implement CES, attributing this to the increased propensity of these companies to innovate, take risks, and engage in green business practices proactively (Ritala et al. 2021). However, the relationship is multifaceted. While GEO provides the vision, CES offers the roadmap. Without a comprehensive CES, the ambitions of GEO might remain unfulfilled. This interplay suggests that firms must ensure a robust corporate environmental strategy to benefit from their green entrepreneurial orientation.

The third hypothesis explores the association between GHC and GSCI. Our findings, derived from the analysis, lend substantial support to Hypothesis 3, indicating a positive correlation between GHC and GSCI. This suggests that firms endowed with a rich reservoir of GHC are better positioned to integrate green practices within their supply chains. Such firms, equipped with the requisite green knowledge and skills, can translate this expertise into actionable strategies, fostering a culture of sustainability and driving tangible change (Liu et al. 2013). The underlying rationale for this relationship is that GHC equips firms with the necessary tools and insights to comprehend the environmental implications of their supply chain activities. A robust GHC level within companies often translates to a more comprehensive green supply chain (Shahid et al. 2020). This is because employees, when armed with eco-friendly knowledge and skills, can guide their organizations in adopting avant-garde green practices, thereby amplifying environmental performance and promoting GSCI. However, while green human capital can provide foundational knowledge and skills, integrating these practices into the supply chain requires various factors, including organizational commitment, supportive infrastructure, and stakeholder alignment (Bhardwaj, 2016). Operational challenges, legacy systems, and resistance to change can be significant impediments, even in firms with substantial GHC. Furthermore, the influence of GHC on GSCI is not universally positive across all sectors and contexts. Specific industries might not prioritize green initiatives as a core competency, leading to variations in the GHC-GSCI relationship (Jabbour and De Sousa Jabbour, 2016). This underscores the importance of contextual considerations in understanding the dynamics of this relationship.

The fourth hypothesis of our study examines the influence of GHC on CES. Our empirical analysis robustly supports Hypothesis 4, revealing a positive correlation between GHC and CES. This suggests that firms with a rich GHC reservoir are more inclined to develop and implement comprehensive environmental strategies. Armed with the requisite green knowledge and expertise, such firms are better positioned to recognize the potential benefits of environmental sustainability, weaving these considerations seamlessly into their corporate strategies (Bhardwaj, 2016). The underlying logic for this relationship is anchored in the premise that employees equipped with green competencies can effectively steer their organizations through the complex landscape of environmental sustainability. They can guide firms in navigating regulatory shifts, understanding environmental challenges, and aligning operations with environmental mandates, all integral components of a robust CES (Munawar et al. 2022). Furthermore, GHC’s influence extends beyond mere strategy formulation; it plays a crucial role in stakeholder management, which is paramount for successfully realizing CES (Tang et al. 2018). However, the relationship is not one-dimensional. While GHC provides the capabilities, CES determines the deployment of these capabilities. This dynamic suggests that for firms to truly harness the benefits of their GHC, they must ensure that they have a strategic framework in the form of CES, which allows for the effective deployment of these capabilities.

Hypothesis 5 is concerned with the relationship between CES and GSCI. Our empirical findings robustly corroborate H5, underscoring a positive association between CES and GSCI. This suggests that firms with a well-articulated CES are more predisposed to integrate green practices across their supply chains. Such organizations, driven by a strategic commitment to environmental sustainability, are better equipped to discern and manage environmental risks along their supply chains, leading to enhanced GSCI (Qi et al. 2010). Wong et al. (2018) further supports this observation, demonstrating that firms that harmonize their CES and GSCI initiatives achieve superior financial outcomes and witness commendable environmental performance.The premise of this relationship is that CES, as a strategic commitment to environmental sustainability, offers a clear roadmap for GSCI. A well-defined CES provides firms with a framework for pursuing green practices, ensuring their supply chains align with overarching environmental goals. This strategic alignment facilitates adopting sustainable procurement practices, effective waste management strategies, and energy-conscious logistics, which are all fundamental to GSCI (Testa et al. 2012). However, the relationship is multifaceted. While CES provides the strategic direction, GSCI represents the tangible manifestation of this strategy. This dynamic underscores the importance of ensuring that the strategic vision provided by CES is effectively translated into actionable steps through GSCI.

Hypotheses 6 and 7 emphasize the mediating role of CES in the relationships between GEO and GSCI and GHC and GSCI, respectively. Hypothesis 6 postulated that CES mediates the relationship between GEO and GSCI. The empirical findings validate this hypothesis, shedding light on the pivotal role CES plays in bridging the gap between a firm’s green entrepreneurial aspirations and its tangible supply chain practices. While GEO sets the strategic intent and vision, it is not always directly translated into actionable GSCI practices. This is where the role of CES becomes paramount. Our findings suggest that CES acts as a strategic roadmap, guiding firms toward operationalizing their green entrepreneurial intentions into concrete GSCI initiatives. Firms with a robust GEO may possess the vision and intent for environmental sustainability, but without a comprehensive CES, they might grapple with the practicalities of integrating these aspirations into their supply chains. CES provides the necessary strategic framework, ensuring that the green entrepreneurial spirit is not just a vision but is embedded in the very fabric of the supply chain operations (Cherrafi et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2016). Furthermore, the mediating role of CES underscores the importance of strategic alignment in achieving GSCI. Firms must ensure their green entrepreneurial orientation aligns with their corporate environmental strategy. A misalignment between the two can lead to operational inefficiencies, hindering the successful integration of green practices within supply chains (Adomako et al. 2021; Criado-Gomis et al. 2017). Environmental strategies channel the strategic impetus for environmental sustainability through green entrepreneurial orientation, leading to innovative GSCI practices. Firms that successfully mediate their GEO through CES are better positioned to innovate in their supply chain processes, leading to enhanced environmental performance and competitive advantage.

Additionally, Hypothesis 7 of our research delved into the mediating role of CES in the relationship between GHC and GSCI. The results from our study affirm this hypothesis, underscoring the pivotal role CES plays in harnessing the potential of GHC to drive GSCI initiatives. GHC fosters eco-innovation and environmental awareness within organizations (Singh et al. 2020). However, possessing green human capital does not automatically guarantee the successful implementation of green supply chain integration. This is where the role of CES becomes instrumental. Our findings suggest that CES acts as a strategic conduit, channeling the capabilities and expertise embedded in GHC toward actionable GSCI practices. While GHC equips firms with the necessary environmental expertise, it is through CES that these competencies are strategically deployed to drive GSCI initiatives (David et al. 2017). In essence, CES provides the strategic direction, ensuring that employees’ environmental knowledge and skills are effectively utilized to enhance green supply chain practices. Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of alignment between GHC and CES. Firms need to ensure that their human capital’s green competencies are in sync with their corporate environmental strategy. A misalignment can lead to operational inefficiencies and missed opportunities in GSCI. There needs to be a strategic harmony between GHC and CES to harness the full potential of GSCI (Trujillo-Gallego et al. 2022). While GHC provides the foundational expertise for environmental sustainability, it is through CES that this expertise is channeled into proactive GSCI practices. Firms that successfully mediate their GHC through CES are better positioned to innovate in their supply chain processes, leading to enhanced environmental performance. This proactive approach to GSCI, driven by the synergistic relationship between GHC and CES, offers firms a competitive edge in the increasingly green-conscious business landscape.

Conclusion and implications

We investigated the interconnection between green entrepreneurial orientation and green human capital and how they collectively impact green supply chain integration, keeping the corporate environmental strategy as the critical context. This study tackled data from senior management across various corporations to authenticate the proposed theoretical framework using reliable and robust statistical methods. The study’s main goal was to inspect the interconnectivity of the variables, including the mediating effects of the mediator variable, and emphasize the potential moderating role of corporate environmental strategy. The results supported all the hypotheses, demonstrating positive connections between the independent factors, the dependent variable, and the mediator variable’s mediating role. This determines the importance of firms lining up their entrepreneurial orientation and human capital with environmental strategies to enhance supply chain integration in an eco-conscious business world. The paper explored the limitations, potential future research scopes, broad theoretical and practical prospects, and implications of this study.

Theoretical implications

This research is a pivotal theoretical advancement in the strategic management literature, particularly within the resource-based view (RBV). By intricately examining the interplay of GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES, it reshapes our understanding of how internal resources can be harnessed for environmental sustainability (Chen et al. 2004; Hitt et al. 2019). It also uncovers the techniques that effectively drive the integration of eco-conscious practices within supply chains by comprehensively drawing from various existing theories. A core theoretical expansion is evident in the nuanced exploration of GEO. While entrepreneurial orientation has been a cornerstone in prior studies, this research uniquely magnifies the ‘green’ dimension, pushing the boundaries of RBV to encapsulate how a sustainability orientation can be a game-changer in the realm of supply chain integration (Wang et al. 2014). Integrating GHC into this framework is another leap, spotlighting the often-underestimated role of human capital in green initiatives. This bridges a theoretical gap and repositions the importance of an environmentally-conscious workforce within the RBV (Singh et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2013). This focuses on the intricate interaction between human resources, sustainability, and supply chain dynamics.

Furthermore, the mediating role of CES in the relationship between GEO, GHC, and GSCI offers a nuanced understanding of how strategic commitment to environmental sustainability can be a linchpin in fostering green supply chain integration (Montabon et al. 2007). This research not only fills the theoretical voids left by previous studies but also provides a holistic perspective on the synergy of these variables, thereby enriching our comprehension of how firms can strategically align their internal resources with environmental imperatives to achieve a competitive edge. This study significantly enhances our theoretical understanding of the complex connections among GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES. It provides an in-depth framework that contributes to sustainable supply chain management discussions by merging various theoretical viewpoints. This study also highlights the importance of a strategic approach to embedding green practices across supply chain operations. This research integrates the four constructs into an integrated framework, addressing theoretical gaps and offering a complete view of how enterprises might strategically align their internal resources with environmental demands. This study substantially enhances the sustainable supply chain management literature by integrating several theoretical perspectives and providing a comprehensive framework for future research.

Managerial implications

This research offers pivotal insights for managers navigating the complexities of today’s environmentally conscious markets. By elucidating the intricate relationships between GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES, our study furnishes actionable strategies for firms aiming to bolster their sustainability initiatives. Our findings underscore the importance of fostering a dynamic GEO within organizations (Brandenburg and Rebs, 2015; Montabon et al. 2016). It encourages a corporate ethos that prioritizes environmental innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking. Such an orientation aligns with overarching sustainability goals and sets the stage for a more integrated GSCI (Adomako et al. 2021; Criado-Gomis et al. 2017). However, the mere presence of a green entrepreneurial mindset is not enough. The role of GHC, the bedrock of eco-friendly knowledge and skills within an organization, is indispensable (Longoni and Cagliano, 2015; Ren et al. 2018). For managers, this translates to a continuous commitment to employee training, ensuring the workforce is adept in green practices (Singh et al. 2020).

CES mediates the relationship between GEO, GHC, and GSCI, ensuring that a firm’s green aspirations and human capital translate into actionable supply chain initiatives (Cherrafi et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2016). A robust CES, deeply embedded in strategic decision-making, acts as a conduit, channeling the ambitions of GEO and the prowess of GHC into tangible GSCI outcomes (David et al. 2017; Hartmann and Moeller, 2014). In essence, our study underscores the need for a holistic sustainability approach. By harmonizing GEO, GHC, and CES, firms can optimize their GSCI, balancing environmental responsibility and market competitiveness (Ahi and Searcy, 2013; Albertini, 2013). Managers equipped with these insights are better positioned to make informed decisions, ensuring their strategies champion environmental sustainability and fortify their market standing and long-term success. The results imply that managers should stimulate an organizational culture of experimentation, risk-taking, and proactivity in pursuing environmentally friendly innovations to leverage advantages from their GEO. Managers stand to benefit most from GEO and GHC at times when CES is not a theoretical framework but an integral part of the daily operation. It can establish cross-functional teams to align supply chain processes to meet environmental objectives, leverage digital tools to monitor and enhance supply chain sustainability metrics and be responsive to any development regarding evolving environmental regulation and market expectations.

SMEs, by their very nature, have tighter financial resources and limited human resource capacity, hence making the development of green capabilities more difficult. For instance, SMEs may focus on step-by-step improvement by adopting modular green training programs for employees, creating local partnerships to share green logistics solutions, or adopting low-cost environmental management tools. For example, cultivating GHC in a phased manner could be the hiring or training of at least one sustainability expert to spearhead eco-initiatives; thereby, smaller firms can lay the foundational green skills and practices without overstretching their resources. On other occasions, companies operating within regions with more stringent controls of environmental degradation or proper green infrastructure in place-e.g., parts of Europe or East Asia can take their CES in direct congruence with the raising and consolidating policy frameworks within well-established green financing for certification programs. Companies operating in emerging markets or located in regions with nascent green infrastructures may find it appropriate to lead through capacity-building efforts: identifying only affordable training modules to build GHC, partnering with NGOs or other local educational institutions to jointly create green competencies, or adopting only scalable technologies that incrementally enhance environmental performance but require limited upfront investments.

Furthermore, governments and other regulatory bodies should encourage specific incentives for firms that display a strong green entrepreneurial orientation or innovative green practices. These incentives might include tax cuts, grants for further research into green technology, or an award to recognize industry leaders in sustainability. Such incentives would likely lead to more companies adopting proactive environmental strategies. Moreover, policymakers should elaborate and advance the frameworks focused on enhancing GHC among sectors. For example, creating uniform certification in green skills, providing subsidies for sustainability-oriented training of employees, or establishing partnerships between educational entities and industries to develop skills in green areas. Finally, public-private partnerships should be encouraged to cooperate in various organizations focused on green supply chain initiatives. Such partnerships will provide firms with needed resources and networks for more effective GSCI implementation.

Limitations and future research directions

Although the research findings offer valuable insights, it is crucial to acknowledge their limits and establish a trajectory for future research to enhance our understanding of green entrepreneurship and corporate strategies. This study’s major limitation includes focusing on Chinese manufacturing firms because it cannot generalize findings to other geographical and industrial contexts. Particular Chinese cultural context, regulatory, and industrial contexts may bias the GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES dynamics in ways that differ from other regions or sectors. Future research should test the proposed framework in diverse geographic and cultural contexts to examine whether the relationships observed in this study hold across different regions and industries. This may include evaluating the functions of GEO and GHC in integrating green supply chains across many sectors, including services, technology, and agriculture, each of which presents unique environmental issues and possibilities. Another notable constraint is its emphasis on larger organizations, which may limit the results’ applicability to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Future research should dive deeper into GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES dynamics, keeping SMEs in the critical context to obtain a more extensive understanding of the area. The use of cross-sectional data in this study is still another drawback. Researchers must shift their focus from cross-sectional observations to longitudinal studies, which provide valuable insights into the dynamic character of these relationships over extended timeframes.

Another limitation pertains to the reliance on self-report measures. While self-reported data facilitated the exploration of perceptions and attitudes, it can introduce response bias and common method variance. Future research could incorporate objective measures or multiple data sources, enhancing the validity of the results. The study would help us decipher the complex interplay between GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES by integrating a temporal viewpoint. It would also be beneficial to inspect the external and internal contextual variables. Various factors, including regional environmental norms, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and internal organizational ethos, significantly influence the dynamics of these relationships and encourage academics to explore relatively uncharted territories. This investigation focuses primarily on the synergistic relationships between factors. However, future research should also investigate the obstacles, inconsistencies, and compromises businesses may encounter when implementing CES into their operational structures. Apart from recognizing that this research focuses on Chinese manufacturing firms, future studies might also be conducted as comparative studies across different sectors and countries to ascertain if cultural, regulatory, and market differences affect relationships among GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES. It would thus be desirable that the frameworks are examined across service-oriented businesses or technology-driven firms in an industry-wide investigation, and cross-country examination, such as emerging versus developed economies, would provide much finer details as to how external contexts shape these relationships. By addressing these limitations and conducting additional research, academics can significantly improve our understanding of the complex relationships among GEO, GHC, GSCI, and CES. This comprehension will be crucial for entrepreneurs and corporate leaders, enabling them to integrate environmental consciousness into their strategic endeavors easily. Firms will be better equipped to navigate the complexities of the green entrepreneurial landscape and will strengthen their competitive standing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are attached as supplementary file.

References

Adomako S, Ning E, Adu-Ameyaw E (2021) Proactive environmental strategy and firm performance at the bottom of the pyramid. Bus. Strategy Environ. 30(1):422–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2629

Aftab J, Abid N, Cucari N, Savastano M (2022) Green human resource management and environmental performance: The role of green innovation and environmental strategy in a developing country. Bus. Strategy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3219

Afum E, Issau K, Agyabeng-Mensah Y, Baah C, Dacosta E, Essandoh E, Agyenim Boateng E (2023) The missing links of sustainable supply chain management and green radical product innovation between sustainable entrepreneurship orientation and sustainability performance. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 21(1):167–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-05-2021-0267

Agyabeng-Mensah Y, Tang L (2021) The relationship among green human capital, green logistics practices, green competitiveness, social performance and financial performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 32(7):1377–1398. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-11-2020-0441

Ahi P, Searcy C (2013) A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 52:329–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.02.018

Al-Hakimi MA, Saleh MH, Borade DB (2021) Entrepreneurial orientation and supply chain resilience of manufacturing SMEs in Yemen: the mediating effects of absorptive capacity and innovation. Heliyon 7(10):e08145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08145

Al-Minhas U, Ndubisi NO, Barrane FZ (2020) Corporate environmental management: A review and integration of green human resource management and green logistics. Manag. Environ. Qual.: Int. J. 31(2):431–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-07-2019-0161

Al-Swidi AK, Al-Hakimi MA, Al-Sarraf J, Al koliby IS (2024) Innovate or perish: can green entrepreneurial orientation foster green innovation by leveraging green manufacturing practices under different levels of green technology turbulence? J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 35(1):74–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-06-2023-0222/FULL/PDF

Albertini E (2013) Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Organ. Environ. 26(4):431–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026613510301