Abstract

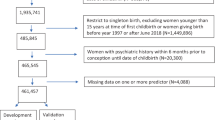

Although the association between partner status and postpartum depression (PPD) is well studied, less is known about how a partner’s psychiatric history affects PPD risk in partnered mothers. Here, using maternal PPD screenings merged with Danish registers from 149,383 childbirths, we examined the influence of partner status and partner mental health on PPD risk. Exposures were partner status and partner psychiatric history, and outcomes were PPD (positive screening) and severe PPD (antidepressants or diagnosis). In total, 14.7% were unpartnered mothers, with a higher risk of PPD (absolute risk (AR) 8.9% versus 7.0%; relative risk (RR) 1.11 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.16)) and severe PPD (AR 1.1% versus 0.9%; RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.86–1.14)) compared with partnered mothers. Among partnered mothers, 19.7% had partners with psychiatric history. Recent psychiatric history increased the risk of PPD (AR 8.3%; RR 1.10 (95% CI 1.02–1.18)) and severe PPD (AR 1.5%; RR 1.42 (95% CI 1.18–1.69)), compared with no psychiatric history. We show that unpartnered mothers face a slightly increased PPD risk, while recent partner psychiatric episodes markedly increase risk in partnered mothers.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

79,00 € per year

only 6,58 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

In accordance with Danish data protection laws, individual-level data are not accessible to the public. The data used for this study are stored on a secure platform at Statistics Denmark and are available upon request to the authors, subject to legal and ethical approvals. Approval can be obtained from Statistics Denmark’s research service.

Code availability

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15. The code used in this study is not publicly available due to data confidentiality regulations within Statistics Denmark but can be shared upon reasonable request, subject to a case-by-case evaluation.

References

Gavin, N. I. et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet. Gynecol. 106, 1071–1083 (2005).

Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A. & Harris, M. G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 219, 86–92 (2017).

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J.-Y. & Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health 15, 1745506519844044 (2019).

Johannsen, B. M. W., Mægbæk, M. L., Bech, B. H., Laursen, T. M. & Munk-Olsen, T. Divorce or separation following postpartum psychiatric episodes: a population-based cohort study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 82, 20m13555 (2021).

Fonseca, A. et al. Emerging issues and questions on peripartum depression prevention, diagnosis and treatment: a consensus report from the cost action riseup-PPD. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 167–173 (2020).

Gidén, K., Vinnerljung, L., Iliadis, S. I., Fransson, E. & Skalkidou, A. Feeling better?—Identification, interventions, and remission among women with early postpartum depressive symptoms in Sweden: a nested cohort study. Eur. Psychiatry 67, e14 (2024).

Motrico, E. et al. Clinical practice guidelines with recommendations for peripartum depression: a European systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 146, 325–339 (2022).

Crosier, T., Butterworth, P. & Rodgers, B. Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers: the role of financial hardship and social support. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 42, 6–13 (2007).

Pao, C., Guintivano, J., Santos, H. & Meltzer-Brody, S. Postpartum depression and social support in a racially and ethnically diverse population of women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 22, 105–114 (2019).

Xie, R. H. et al. Prenatal family support, postnatal family support and postpartum depression. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 50, 340–345 (2010).

Yim, I. S., Tanner Stapleton, L. R., Guardino, C. M., Hahn-Holbrook, J. & Schetter, C. D. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: systematic review and call for integration. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 11, 99–137 (2015).

Paulson, J. F., Bazemore, S. D., Goodman, J. H. & Leiferman, J. A. The course and interrelationship of maternal and paternal perinatal depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 19, 655–663 (2016).

Thiel, F., Pittelkow, M.-M., Wittchen, H.-U. & Garthus-Niegel, S. The relationship between paternal and maternal depression during the perinatal period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 11, 563287 (2020).

Agnafors, S., Bladh, M., Svedin, C. G. & Sydsjö, G. Mental health in young mothers, single mothers and their children. BMC Psychiatry 19, 112 (2019).

Volgsten, H. & Schmidt, L. Motherhood through medically assisted reproduction—characteristics and motivations of Swedish single mothers by choice. Hum. Fertil. 24, 219–225 (2021).

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. & Wilson, S. J. Lovesick: how couples’ relationships influence health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 13, 421–443 (2017).

Bedaso, A., Adams, J., Peng, W. & Sibbritt, D. The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Health 18, 162 (2021).

Khademi, K. & Kaveh, M. H. Social support as a coping resource for psychosocial conditions in postpartum period: a systematic review and logic framework. BMC Psychol. 12, 301 (2024).

Kay, T. L., Moulson, M. C., Vigod, S. N., Schoueri-Mychasiw, N. & Singla, D. R. The role of social support in perinatal mental health and psychosocial stimulation. Yale J. Biol. Med. 97, 3–16 (2024).

Westdahl, C. et al. Social support and social conflict as predictors of prenatal depression. Obstet. Gynecol. 110, 134–140 (2007).

Riem, M. M. E., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Cima, M. & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. Grandparental support and maternal postpartum mental health: a review and meta-analysis. Hum. Nat. 34, 25–45 (2023).

García, D., Vassena, R. & Rodríguez, A. Single women and motherhood: right now or maybe later? J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 41, 69–73 (2020).

Chasson, M. & Taubman-Ben-Ari, O. Personal growth of single mothers by choice in the transition to motherhood: a comparative study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 39, 301–312 (2021).

De Sousa Machado, T., Chur-Hansen, A. & Due, C. First-time mothers’ perceptions of social support: recommendations for best practice. Health Psychol. Open 7, 2055102919898611 (2020).

Noordzij, M., Van Diepen, M., Caskey, F. C. & Jager, K. J. Relative risk versus absolute risk: one cannot be interpreted without the other. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 32, ii13–ii18 (2017).

Zacher Kjeldsen, M.-M. et al. The HOPE cohort: cohort profile and evaluation of selection bias. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 39, 943–954 (2024).

Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020); https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192/resources/antenatal-and-postnatal-mental-health-clinical-management-and-service-guidance-pdf-35109869806789

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 4. Obstet. Gynecol. 141, 1232–1261 (2023).

Documentation of Statistics for The Population 2024 (Statistics Denmark, 2024); https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/dokumentation/statistikdokumentation/befolkningen

Mors, O., Perto, G. P. & Mortensen, P. B. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand. J. Public Health 39, 54–57 (2011).

Pottegård, A. et al. Data Resource Profile: the Danish National Prescription Registry. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 798–798f (2017).

Smith-Nielsen, J., Matthey, S., Lange, T. & Væver, M. S. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry 18, 393 (2018).

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 150, 782–786 (1987).

Pedersen, C. B. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand. J. Public Health 39, 22–25 (2011).

Jensen, V. M. & Rasmussen, A. W. Danish education registers. Scand. J. Public Health 39, 91–94 (2011).

International Standard Classification of Education: ISCED 2011 (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012).

Bliddal, M., Broe, A., Pottegård, A., Olsen, J. & Langhoff-Roos, J. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 33, 27–36 (2018).

Hutchens, B. F. & Kearney, J. Risk factors for postpartum depression: an umbrella review. J. Midwifery Womens Health 65, 96–108 (2020).

Zacher Kjeldsen, M.-M. et al. Family history of psychiatric disorders as a risk factor for maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 1004–1013 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the parents, healthcare nurses and participating municipalities for granting access to the postpartum depression screenings. M.-M.Z.K., M.L.M. and T.M.-O. are funded by The Lundbeck Foundation (grant no. R313-2019-569). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-M.Z.K. led the work under supervision of T.M.-O. M.-M.Z.K., X.L., K.B.M., A.F.E., S.Z.K., M.L.M., V.B., V.G.F. and T.M.-O. contributed to the study conception and design. M.-M.Z.K., K.B.M. and T.M.-O. contributed to the data acquisition. Data analyses were performed by M.-M.Z.K. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.-M.Z.K., and M.-M.Z.K., X.L., K.B.M., A.F.E., S.Z.K., M.L.M., V.B., V.G.F. and T.M.-O. critically revised it. M.-M.Z.K., X.L., K.B.M., A.F.E., S.Z.K., M.L.M., V.B., V.G.F. and T.M.-O. read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.B.M. has received speaker’s fee from Medice Nordic in the past 3 years. T.M.-O. has received speaker’s fee from Lundbeck A/S during the same period. V.G.F. has served as a lecturer for Lundbeck A/S, Janssen-Cilag, Gedeon Richter and Ferring Pharmaceuticals in the past 3 years. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Catherine Monk, Bing Xiang Yang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zacher Kjeldsen, MM., Liu, X., Bang Madsen, K. et al. Partner status and partner mental health and the risk of postpartum depression. Nat. Mental Health (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00461-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00461-z