Abstract

Transition-metal-catalysed asymmetric multicomponent reactions with two similar substrates often suffer from the lack of strategies to control the chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity of these substrates due to the close similarity in the chemical structures and properties of each reagent. Here, we describe a Cu(I)-catalysed asymmetric radical 1,2-carboalkynylation of two different terminal alkynes and alkyl halides with high chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity by using sterically bulky chiral tridentate anionic N,N,P-ligands and modulating alkynes with different electronic properties to circumvent above-mentioned challenges. This method features good substrate scope, high functional group tolerance of two different terminal alkynes, and diverse alkyl halides, providing universal access to a series of useful axially chiral 1,3-enyne building blocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multicomponent reactions have been identified as a prominent strategy for the rapid generation of molecular complexity1,2,3,4,5,6. The key to the success of multicomponent reactions is to meticulously ensure the compatibility of each step, allowing the simultaneous addition of all reactants and catalysts at the onset of the reaction. Among numerous processes, transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric multicomponent radical reactions have gained considerable interest due to their remarkable compatibility with many functional groups and unique reactivity profile7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. To ensure high levels of chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity, one variant of this process is to combine reactants possessing different reactivities (Fig. 1a, left). Another type of reaction is to utilize easily available reactants with close similarity in the chemical structures and properties (Fig. 1a, right). The similarity would undoubtedly increase the complexity of reaction pathway, making it difficult to achieve a delicate balance among chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity.

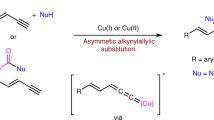

a Transition-metal catalyzed three-component asymmetric radical reactions. b Challenges for asymmetric radical difunctionalization of two different terminal alkynes. c Cu(I)-catalyzed enantioselective radical 1,2-carboalkynylation with two terminal alkynes. M metal, tBu tert-butyl, Ar aryl, iPr isopropyl, Tf trifluoromethanesulfonyl, Cz carbazolyl.

Conjugated 1,3-enynes are important structural units in organic synthesis, serving as precursors for polysubstituted aromatic rings, biologically active molecules, and organic materials16,17,18,19. Although many strategies have been developed for the construction of 1,3-enynes20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, the direct coupling of alkynes to 1,3-enynes via a radical relay pathway has been rarely reported30,31,32,33,34. In this context, Wu30, Koenigs31, and others32 have reported the Pd-catalyzed dicarbofunctionalization of terminal alkynes using secondary or tertiary alkyl iodide, including radical Mizoroki−Heck reactions for the synthesis of 1,3-enynes. Nishikata and co-workers demonstrated a copper-catalyzed tandem radical addition/Sonogashira-coupling process using alkyl bromides and terminal alkynes33. However, the limitation of the above processes stems from the use of the same alkyne in both steps of the tandem process, which ultimately results in the installation of two identical substituents on the enyne motifs. To increase the diversity of 1,3-enynes, the Koh group made a breakthrough using structurally different bromoalkynes as the coupling partners to achieve the 1,2-carboalkynyaltion of terminal alkynes34. Despite these impressive advances, the development of a catalytic version of two similar terminal alkynes to realize highly chemo- and regioselective control is still challenging. Moreover, despite the recent enormous development of radical asymmetric catalysis35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52, the enantioselective radical difunctionalization of two different terminal alkynes with simple radical precursors to give the axially chiral 1,3-enyne frameworks53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82 remains unexploited (Fig. 1b). In addition to innate reactions of terminal alkynes and alkyl halides, such as Glaser-homocoupling83,84,85, halogen atom transfer reaction22,86,87,88,89, and Sonogashira-coupling90,91,92, this reaction suffers from additional challenges: (1) how to achieve the chemoselectivity between vinyl radical I and II, which are generated from the two terminal alkynes93,94,95,96,97 (Fig. 1b); (2) how to ensure the chemo-, and stereoselectivity in the coupling of vinyl radical with the Mn+1L*–acetylide complex (Fig. 1b, yne-Ar and yne-R1). Therefore, developing a new strategy to synthesize axially chiral 1,3-enynes with high chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity is urgently needed. To address these challenges, we expected to chemoselectively control the vinyl radical generation to give radical I by regulating the electronic properties of two different terminal alkynes (Fig. 1b, route a). We anticipated that our recently developed copper catalysts with steric crowded chiral multidentate anionic ligands91,92,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106, could selectively promote deprotonation of alkyne with smaller substitute R1 to generate less steric crowded Mn+1L*–acetylide complex yne-R1. At the same time, the thus-generated yne-R1 intermediate with low steric congestion might also prefer to trap vinyl radical I, therefore not only controlling the desired asymmetric process91,98,99,100,101,102,103 but also overcoming the readily occurring side reactions to afford axially chiral 1,3-enynes with high chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity.

Herein, we report a copper-catalyzed three-component asymmetric radical 1,2-carboalkynylation using two different terminal alkynes, providing a straightforward route to a diverse array of axially chiral 1,3-enynes (Fig. 1c). This protocol exhibits excellent chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity under mild conditions, featuring a broad substrate scope of readily available terminal alkynes and high functional group tolerance, enabling the synthesis of a variety of axially chiral 1,3-enynes. Furthermore, the reaction could be scaled up, and the resulting axially chiral 1,3-enynes could be easily transformed into a series of useful axially chiral 1,3-enyne building blocks.

Results

Reaction development

To examine our aforementioned proposal, aryl alkyne S1 with a large 2-substitutent was selected as the model coupling alkyne, therefore hoping not only to generate the conjugation-stabilized vinyl radical but also to introduce axial chirality. Alkyl alkyne S16, which lacked conjugation effect and would generate thermodynamically unfavorable vinyl radical, was used as the nucleophile to construct 1,3-enyne skeletons. Also, copper salts with chiral ligands would undergo single-electron transfer (SET) with tert-butyl α-bromoisobutyrate C1 to initiate this reaction, giving rise to the alkyl radical. At first, a screening of bidentate neutral ligands, such as bisoxazoline-based ligand L*1 and phosphinooxazoline ligand L*2, with CuTc as the catalyst, indicated no reaction activity, presumably due to the insufficient reducing capability of the copper complex (entries 1–2; Table 1). Thus, we tested chiral anionic oxazoline-derived N,N,N-ligand L*3, which have shown enough reducing capability of copper catalyst to reduce tertiary alkyl bromide in our previous report104,105. Indeed, the desired product 1 was obtained in 28% yield, albeit with low enantioselectivity (10% e.e.) along with the homocoupling side product 1’ in a higher yield than 1, and 14% yield of atom transfer side product 1” (entry 3, and also see Supplementary Table 3), demonstrating the competence of the N,N,N-coordination manifold in promoting the desired reaction. Interestingly, the reaction using the cinchona alkaloid-derived tridentate picolinamide L*4106 still suffered from alkyne homocoupling. To our surprise, tridentate N,N,P-tridentate ligand L*591,107, gave the desired product 1 in 56% e.e., albeit with low yield while inhibiting the alkyne homocoupling process (entry 5). Encouraged by this finding, we next examined the other steric bulk N,N,P-tridentate ligand L*6 and found that the reaction provided product 1 in 77% e.e. but the reaction efficiency remained low (entry 6). Accordingly, we next sought to install a sterically bulky 3,5-disubstituted phenyl ring in L*7, and the e.e. increased to 87% (entry 7). Replacing the key chiral skeleton with cyclohexylenediamine of L*8 significantly improved the yield of 1 to 75% with enhanced enantioselectivity (89% e.e.) with excellent chemo- and regioselectivity. Collectively, these results indicated that the use of bulky N,N,P-tridentate ligand L*8 is crucial for not only selectively generating less steric CuIL*–acetylide complex through deprotonation of smaller-sized alkyne S16 but also effectively interacting vinyl radical I with thus-generated CuIL*–acetylide complex due to low steric congestion, which would exert effective cross-coupling to give 1 while inhibiting side self-coupling and atom transfer processes. Further optimization of conditions, including copper salts, bases, solvents, reaction time and other factors (see Supplementary Tables 1‒7 for the results of condition screening), identified the optimal conditions (entry 9) as follows: S1 (2.0 equiv.), C1 (2.0 equiv.) and S16 (0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in the presence of CuTc (10 mol%), L*8 (12 mol%), and Cs2CO3 (5.0 equiv.) in Et2O at 10 °C for 5 days under argon. This condition provided 1 in 72% yield and 93% e.e. with excellent chemo- and regioselectivity.

Substrate scope

Considering the high utility of axially chiral phenol compounds108,109, we first investigated the reaction with 2-oxyaryl alkynes, and those bearing a wide range of functional groups with different electronic properties were readily accommodated in this reaction. As for the scope of 2-oxyaryl alkynes, a series of 6-substituted naphthyl rings were readily accommodated in this reaction (2–5; Fig. 2a). However, 6- and 7-phenyl-subsituted aryl alkynes suffered from a low conversion to afford the desired products 3 and 6 in low yield, likely due to steric hindrance of the phenyl substituent. Furthermore, various 4- and/or 5-substituted naphthyl rings underwent the reaction smoothly, delivering the corresponding products 7–9 in 62−70% yield with 91−92% e.e. Likewise, good tolerance of 5- and/or 6-substitution of 2-oxyphenyl alkyne substrates was also observed (10 and 11). In addition, 4,6-disubstituted 2-oxyphenyl alkyne was also applicable to this reaction, affording good enantioselectivity and high yield (12). As for the other ortho-oxygen-substituted alkynes, such as carboxylic, proved to be workable in this reaction, providing the desired products (13 and 14) with high enantioselectivity and moderate yield. However, for ortho-nitrogen-substituted groups like pivaloyamine, the corresponding products 15 was obtained with decreased enantioselectivity under the standard reaction conditions. To further improve enantioselectivity, after systematic optimization efforts (see Supplementary Table 8 for condition optimizations), we found that the more sterically hindered cinchona alkaloid-derived N,N,P-L*11 was able to control enantioselectivity, affording the final product 15 with 70% yield and 86% e.e. (Fig. 2b). As for the ortho-carbon-based alkynes, such as phenyl (S28) and isopropyl (S29), the desired products P1 and P2 were obtained with low yield and e.e. (see Supplementary Fig. 4). These results demonstrated the crucial role of the oxygen- and nitrogen-containing functional groups at the ortho positions. The ortho-(O)PPh2 substituted alkyne S30 failed to afford the desired product possibly due to the catalyst poisoning by the diphenyl phosphine oxide group (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Substrate scope for 2-oxyaryl alkynes. Standard reaction conditions: 2-oxyaryl alkynes (2.0 equiv.), C1 (2.0 equiv.), S16 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), CuTc (10 mol%), L*8 (12 mol%), and Cs2CO3 (5.0 equiv.) in Et2O (4.0 mL) at 10 °C for 5 d under argon. b ortho-N-substituted group. Standard reaction conditions: 2-aminoaryl alkyne S15 (2.0 equiv.), C1 (2.0 equiv.), S16 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), CuTc (10 mol%), L*11 (12 mol%), and Cs2CO3 (5.0 equiv.) in Et2O (4.0 mL) at r.t. for 5 d under argon. bConducted at r.t. Isolated yield was shown; E.e. values were based on chiral HPLC analysis; FG functional group, Tol tolyl, Me methyl.

We then turned our attention to the scope of radical precursors (Fig. 3a). Numerous α-bromo alkyl and aryl esters including ethyl (C2), cyclopentyl (C3), 4-methoxybenzyl (C4), and tolyl (C5) were effective for the reaction to deliver the corresponding products 16−19 with good efficiency and stereoselectivity. Furthermore, the cyclic α-bromoesters (C6) also participated readily in the reaction, producing 20 in moderate yield and excellent enantioselectivity. In addition, tertiary alkyl bromides with α-amide functional group exhibited good reactivity to produce 21 in 78% yield with 99% e.e. It’s worth noting that the Weinreb amide-type bromide C8 was also compatible with the reaction, affording 22 in 30% yield with 92% e.e. However, tertiary α-bromo ketone failed to give the desired product (see Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, primary and secondary alkyl bromides, such as (bromomethyl)benzene, ethyl 2-bromoacetate, 2-bromoacetonitrile, (3-bromoprop-1-yn-1-yl)trimethylsilane, (bromomethylene)dibenzene, and diethyl 2-bromomalonate as well as Togni reagent, and tosyl chloride were not suitable for the reactions (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for more details). We then proceeded to investigate the scope of alkyne nucleophiles. Regarding the alkyne scope, many alkyl alkynes with aliphatic chains or a variety of functional groups, such as ester (23), ether (24), benzyloxy (25), p-toluenesulfonyloxy (26), carbamate (27) as well as phenylamine (28), underwent the reaction smoothly to generate 23–28 in moderate to good yield with excellent chemo-, regio- and enantioselectivity. Notably, the low yield of 25–27 is due to the low conversion of the corresponding alkyl alkynes.

a Scope of radical precursors and alkyl alkyne nucleophiles. Standard reaction conditions: S1 (2.0 equiv.), S16‒22 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), radical precursor C1‒8 (2.0 equiv.), CuTc (10 mol%), L*8 (12 mol%), and Cs2CO3 (5.0 equiv.) in Et2O (4.0 mL) at 10 °C for 5 d under argon. b Scope of aryl alkyne nucleophiles. Standard reaction conditions: S1 (2.0 equiv.), S23‒27 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), C1 (2.0 equiv.), CuTc (10 mol%), L*8 (12 mol%), and Cs2CO3 (5.0 equiv.) in Et2O (4.0 mL) at 10 °C for 5 d under argon. Isolated yield was shown; E.e. values were based on chiral HPLC analysis. Et ethyl, PMB 4-methoxybenzyl, Ac acetyl, Bn benzyl, Ts p-toluenesulfonyl, Ph phenyl, Boc t-butoxycarbonyl.

Unlike alkyl alkynes, aryl alkynes appeared to be more similar to S1 in chemical properties, which should pose a greater challenge in controlling the chemo-, regio-, and stereoselective. Based on radical polarity properties96,97, we proposed that tuning the electronic properties of two similar terminal alkynes may influence the chemoselectivity of the radical addition, in which in-situ generated electrophilic tertiary alkyl radical from α,α-dimethyl-α-bromoesters would easily prefer to attack aryl alkyne S1 than more electron-withdrawing aryl alkynes. In order to realize such transformation with excellent selectivity, aryl alkynes bearing diverse electron-withdrawing groups (chloride, methoxycarbonyl, trifluoromethyl, and cyano) on the phenyl rings were selected as the nucleophile. Indeed, the reaction worked smoothly to afford the corresponding products 29–32 in 40–58% yield with 80–83% e.e. (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, heteroaryl alkyne featuring pyridine (33) was suitable substrate to give the desired product in 40% yield with 84% e.e. These results demonstrated the importance of radical polarity to achieve asymmetric multicomponent process involving two similar terminal aryl alkynes with high chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity.

Synthetic utility

To demonstrate the synthetic potential of these axially chiral 1,3-enynes products, we first carried out gram-scale reactions with 2-oxyaryl alkyne substrate S1 (Fig. 4a) and still obtained good yield and excellent enantioselectivity (1.96 g, 61% yield, and 92% e.e.). Next, we examined their thermal stability and observed marginal racemization up to 70 °C (see Supplementary Table 9 for more details). As is well known, axially chiral styrene compounds have proven to be a valuable chiral backbone for developing chiral catalysts or ligands in asymmetric catalysis59,64,77,110,111,112,113. To our delight, product 1 could be efficiently converted to corresponding triflate 34 in 41% overall yield with 92% e.e. (Fig. 4b), which has the potential to be a valuable partner in transition metal-catalyzed coupling reactions for constructing variety of axially chiral 1,3-enyne building blocks. Likewise, the configurational stability of product 33 was examined, and only marginal racemization was observed up to 80 °C (see Supplementary Table 10 for more details). The trivalent phosphine-based 35, of which had the potential for asymmetric catalysis, could be easily synthesized by Ni-catalyzed coupling of 34 with Ph2PH at 80 °C in 65% yield and 91% e.e. (Fig. 4c, left)114. Furthermore, Pd-catalyzed coupling of 34 with Ph2P(O)H at 80 °C provided the diphenyl phosphine oxide product 36 in a moderate yield with 90% e.e. (Fig. 4c, right)115. In addition, the absolute structure of product 1b (Fig. 4b, and also see Supplementary Fig. 1) was determined to be Ra by X-ray structural analysis. Finally, we performed a preliminary investigation on the application of axially chiral compounds 35 and 36 as ligand in the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric cross-coupling116. As shown in Fig. 4d, diphenylphosphine 35 could catalyze the Suzuki−Miyaura cross-coupling of 37 and 38 as a potential ligand, affording the coupling product 39 with moderate yield and enantioselectivity, while diphenyl phosphine oxide 36 failed to afford the coupling product. These results demonstrate that the axially chiral 1,3-enyne scaffolds are promising for developing a new class of chiral monophosphine ligand.

a Gram-scale reactions. b, c Transformation of enantioenriched axially chiral 1,3-enynes. d Chiral styrenes 35 and 36 as potential ligand in the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric cross-coupling. aConditions: (i) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C, Ar, 4 h; (ii) MeI, NaH, THF, 0 °C, Ar, 4 h; (iii) DIBAL-H, DCM, ‒78 °C to r.t., Ar, 4 h; (iv) Tf2O, pyridine, DCM, 0 °C to r.t., Ar, 4 h. bConditions for 35: Ni(COD)2, dppf, HPPh2, Na2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, 80 °C, Ar, 3 d. cConditions for 36: Pd(OAc)2, dppb, HP(O)Ph2, DIPEA, DMSO, 80 °C, Ar, 3 d. LiAlH4 lithium aluminum hydride, THF tetrahydrofuran, DCM dichloromethane, DMSO dimethyl sulfoxide, COD 1,5-cyclooctadiene, DIBAL-H diisobutylaluminium hydride, dppf 1,1’-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene, dppb 1,4-bis(diphenylphosphino)butane, DIPEA N,N-diisopropylethylamine, HPPh2 diphenylphosphine, HP(O)Ph2 diphenylphosphine oxide.

Mechanistic investigations

Control experiments conducted in the absence of the copper salt, chiral ligand, or base additive confirmed that all of these components were indispensable for the reaction (see Supplementary Table 11 for more details). The preliminary results of deprotonation experiments suggested that the less steric alkyl alkyne S16 was consumed more rapidly than S1 (see Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), which might probably indicate the sterically bulky CuIL*8 complex would favor deprotonation of less steric alkyne (Fig. 5c). In the presence of either BHT or TEMPO, the reaction was completely inhibited (Fig. 5a). Additionally, the BHT-trapped product 40 was isolated in 77% yield and the TEMPO adducts could be detected by high-resolution mass spectrometry (Fig. 5a, and also see Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, introducing an additional radical trapper, such as phenyl diselenide, resulted in the formation of vinyl radical trapped product 41 in 99% yield with 0% e.e. (Fig. 5a)82. These radical inhibition experiment results indicated the formation of an alkyl radical, which preferentially added to aryl alkynes S1, generating the conjugation-stabilized vinyl radical IV (Fig. 5c). An additional control experiment with alkenyl bromide 1” failed to produce any product 1 under the standard conditions (Fig. 5b), indicating that a tandem atom-transfer radical addition/cross-coupling reaction pathway21 is unlikely.

a Radical inhibition experiments with BHT, TEMPO, and phenyl diselenide. b Control experiments of vinyl bromide with S16. c Mechanistic proposal for the formation of axially chiral 1,3-enynes. aThe yield of 41 was calculated based on the amount of phenyl diselenide. BHT butylated hydroxytoluene, TEMPO 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperinedinyloxy.

Based on these results as well as previous reports90,91,92,98,99,100,101,102,103, we propose a plausible reaction mechanism, as shown in Fig. 5c. Copper(I) salt first coordinated with L*8 to form the catalytically active species CuIL*8, entering the catalytic cycle. Then, complex CuIL*8 selectively reacted with smaller-sized terminal alkyne S-R1 to generate the less steric CuIL*8–acetylide complex I-R1 in the presence of a base91. Afterwards, complex I-R1 underwent single-electron transfer (SET)98 with alkyl bromide, giving rise to the CuIIL*8–acetylide complex II-R1 and alkyl radical III. The following selectively intermolecular addition of III to the triple bond of alkyne S-Ar afforded the conjugation-stabilized vinyl radical IV22. Next, radical IV interacted with complex II-R1 to deliver the desired axially chiral 1,3-enyne products 1‒33 and regenerated the CuIL*8 complex in the presence of the highly sterically demanded ligand L*8. However, we do not have enough evidence to support the proposed process with excellent control of chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity and are currently performing more experimental and theoretical studies to disclose the detailed mechanism.

Discussion

In sum, we have demonstrated a three-component asymmetric radical 1,2-carboalkynylation with two different terminal alkynes and diverse alkyl radical precursors, which could successfully access axially chiral 1,3-enynes with excellent chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity under copper catalysis. The key to success lies not only in using the sterically bulky chiral multidentate anionic N,N,P-ligand but also in modulating alkynes with significantly different electronic properties to tune selectivity. This process features good substrate scope and functional group tolerance of terminal alkynes and radical precursors and readily affords an abundance of valuable enantioenriched axially chiral 1,3-enynes, thus providing a robust platform for expedient access to a myriad of chiral styrene building blocks. These results highlight the great potential of strategically devised multidentate anionic ligands for controlling the asymmetric multicomponent radical reactions with excellent selectivity.

Methods

Representative procedure for axially chiral 1,3-enynes

An oven-dried resealable Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with 2-substituted aryl alkynes (0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), alkyne nucleophiles (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), CuTc (3.8 mg, 0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), L*8 (17.6 mg, 0.024 mmol, 12 mol%), and anhydrous Cs2CO3 (325.8 mg, 1.00 mmol, 5.0 equiv.). The tube was evacuated and backfilled with argon three times. Then Et2O (4.0 mL) was added by syringe under argon atmosphere. Finally, radical precursor (0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) was added into the mixture and the reaction mixture was stirred at 10 °C for 5 d. Upon completion of the reaction (monitored by TLC), the reaction mixture was filtered through a short pad of Celite and washed with EtOAc. The filtrate was concentrated to afford the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired product.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text and Supplementary Information and also available from the corresponding author upon request. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2403993 (1b) [https://doi.org/10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2lpk51]. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

References

Ramón, D. J. & Yus, M. Asymmetric multicomponent reactions (AMCRs): the new frontier. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 1602–1634 (2005).

Ruijter, E., Scheffelaar, R. & Orru, R. V. A. Multicomponent reaction design in the quest for molecular complexity and diversity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6234–6246 (2011).

Dömling, A., Wang, W. & Wang, K. Chemistry and biology of multicomponent reactions. Chem. Rev. 112, 3083–3135 (2012).

Estévez, V., Villacampa, M. & Menéndez, J. C. Recent advances in the synthesis of pyrroles by multicomponent reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 4633–4657 (2014).

John, S. E., Gulati, S. & Shankaraiah, N. Recent advances in multi-component reactions and their mechanistic insights: a triennium review. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 4237–4287 (2021).

Yi, R., Li, Q., Liu, H. & Wei, W. T. Recent advancements in metal‐catalyst‐free multicomponent radical sulfonylation of alkynes. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202401386 (2024).

de Graaff, C., Ruijter, E. & Orru, R. V. A. Recent developments in asymmetric multicomponent reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 3969–4009 (2012).

Li, Z.-L., Fang, G.-C., Gu, Q.-S. & Liu, X.-Y. Recent advances in copper-catalysed radical-involved asymmetric 1,2-difunctionalization of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 32–48 (2020).

Gu, Q.-S., Li, Z.-L. & Liu, X.-Y. Copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric reactions involving radicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 170–181 (2020).

Kanti Das, K., Manna, S. & Panda, S. Transition metal catalyzed asymmetric multicomponent reactions of unsaturated compounds using organoboron reagents. Chem. Commun. 57, 441–459 (2021).

Zhu, S., Zhao, X., Li, H. & Chu, L. Catalytic three-component dicarbofunctionalization reactions involving radical capture by nickel. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 10836–10856 (2021).

Xu, L., Wang, F., Chen, F., Zhu, S. & Chu, L. Recent advances in photoredox/nickel dual-catalyzed difunctionalization of alkenes and alkynes. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 42, 1–15 (2022).

Dong, Z., Song, L. & Chen, L.-A. Enantioselective Ni‐catalyzed three‐component dicarbofunctionalization of alkenes. ChemCatChem 15, e202300803 (2023).

Han, J., He, R. & Wang, C. Transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric three-component dicarbofunctionalization of unactivated alkenes. Chem. Catal. 3, 100690 (2023).

Wang, P.-Z., Zhang, B., Xiao, W.-J. & Chen, J.-R. Photocatalysis meets copper catalysis: a new opportunity for asymmetric multicomponent radical cross-coupling reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 3433–3448 (2024).

Goldberg, I. H. Mechanism of neocarzinostatin action: role of DNA microstructure in determination of chemistry of bistranded oxidative damage. Acc. Chem. Res. 24, 191–198 (1991).

Nicolaou, K. C., Dai, W.-M., Tsay, S.-C., Estevez, V. A. & Wrasidlo, W. Designed enediynes: a new class of DNA-cleaving molecules with potent and selective anticancer activity. Science 256, 1172 (1992).

Stang, P. J. & Diederich, F. Modern Acetylene Chemistry (VCH, 1995).

Weissig, P. & Müller, G. The dehydro-diels−alder reaction. Chem. Rev. 108, 2051–2063 (2008).

Trost, B. M. & Masters, J. T. Transition metal-catalyzed couplings of alkynes to 1,3-enynes: modern methods and synthetic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2212–2238 (2016).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wang, J. Recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed synthesis of conjugated enynes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 6638–6650 (2016).

Che, C., Zheng, H. & Zhu, G. Copper-catalyzed trans-carbohalogenation of terminal alkynes with functionalized tertiary alkyl halides. Org. Lett. 17, 1617–1620 (2015).

Wang, N.-N. et al. Synergistic rhodium/copper catalysis: synthesis of 1,3-enynes and N-aryl enaminones. Org. Lett. 18, 1298–1301 (2016).

Rivada‐Wheelaghan, O., Chakraborty, S., Shimon, L. J. W., Ben‐David, Y. & Milstein, D. Z-selective (cross-)dimerization of terminal alkynes catalyzed by an iron complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 6942–6945 (2016).

Lee, J. T. D. & Zhao, Y. Access to acyclic Z‐enediynes by alkyne trimerization: cooperative bimetallic catalysis using air as the oxidant. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13872–13876 (2016).

Gorgas, N. et al. Stable, yet highly reactive nonclassical iron(II) polyhydride pincer complexes: Z-selective dimerization and hydroboration of terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8130–8133 (2017).

Yan, Z., Yuan, X.-A., Zhao, Y., Zhu, C. & Xie, J. Selective hydroarylation of 1,3‐diynes using a dimeric manganese catalyst: modular synthesis of Z‐enynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12906–12910 (2018).

Cembellín, S., Dalton, T., Pinkert, T., Schäfers, F. & Glorius, F. Highly selective synthesis of 1,3-enynes, pyrroles, and furans by manganese(I)-catalyzed C–H activation. ACS Catal. 10, 197–202 (2020).

Mondal, S. et al. Pd‐catalyzed tandem pathway for stereoselective synthesis of (E)‐1,3‐enyne from β‐nitroalkenes by using a sacrificial directing group. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202301637 (2023).

Qi, X. et al. Palladium‐catalyzed selective synthesis of perfluoroalkylated enynes from perfluoroalkyl iodides and alkynes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2940–2943 (2017).

Yang, Z. & Koenigs, R. M. Photoinduced palladium‐catalyzed dicarbofunctionalization of terminal alkynes. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 3694–3699 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Palladium-catalyzed one-pot construction of difluorinated 1,3-enynes from α,α,α-iododifluoroacetones and alkynes. Tetrahedron 75, 130715 (2019).

Hirata, G., Yamane, Y., Tsubaki, N., Hara, R. & Nishikata, T. Controlling alkyne reactivity by means of a copper-catalyzed radical reaction system for the synthesis of functionalized quaternary carbons. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 16, 502–508 (2020).

Jiang, Y., Pan, J., Yang, T., Zhao, Y. & Koh, M. J. Nickel-catalyzed site- and stereoselective reductive alkylalkynylation of alkynes. Chem. 7, 993–1005 (2021).

Sibi, M. P., Manyem, S. & Zimmerman, J. Enantioselective radical processes. Chem. Rev. 103, 3263–3295 (2003).

Cherney, A. H., Kadunce, N. T. & Reisman, S. E. Enantioselective and enantiospecific transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organometallic reagents to construct C–C bonds. Chem. Rev. 115, 9587–9652 (2015).

Choi, J. & Fu, G. C. Transition metal–catalyzed alkyl-alkyl bond formation: Another dimension in cross-coupling chemistry. Science 356, eaaf7230 (2017).

Silvi, M. & Melchiorre, P. Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature 554, 41–49 (2018).

Wang, F., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed radical relay for asymmetric radical transformations. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2036–2046 (2018).

Milan, M., Bietti, M. & Costas, M. Enantioselective aliphatic C–H bond oxidation catalyzed by bioinspired complexes. Chem. Commun. 54, 9559–9570 (2018).

Huang, X. & Meggers, E. Asymmetric photocatalysis with bis-cyclometalated rhodium complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 833–847 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Iron- and cobalt-catalyzed C(sp3)–H bond functionalization reactions and their application in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5310–5358 (2020).

Proctor, R. S. J., Colgan, A. C. & Phipps, R. J. Exploiting attractive non-covalent interactions for the enantioselective catalysis of reactions involving radical intermediates. Nat. Chem. 12, 990–1004 (2020).

Yin, Y., Zhao, X., Qiao, B. & Jiang, Z. Cooperative photoredox and chiral hydrogen-bonding catalysis. Org. Chem. Front. 7, 1283–1296 (2020).

Xiong, T. & Zhang, Q. Recent advances in the direct construction of enantioenriched stereocenters through addition of radicals to internal alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 8857–8873 (2021).

Lipp, A., Badir, S. O. & Molander, G. A. Stereoinduction in metallaphotoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 1714–1726 (2021).

Zhang, C., Li, Z.-L., Gu, Q.-S. & Liu, X.-Y. Catalytic enantioselective C(sp3)–H functionalization involving radical intermediates. Nat. Commun. 12, 475 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed radical relay in C(sp3)–H functionalization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 1640–1658 (2022).

Mondal, S. et al. Enantioselective radical reactions using chiral catalysts. Chem. Rev. 122, 5842–5976 (2022).

Wang, P.-Z., Chen, J.-R. & Xiao, W.-J. Emerging trends in copper-promoted radical-involved C–O bond formations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17527–17550 (2023).

Lee, W.-C. C. & Zhang, X. P. Metalloradical catalysis: general approach for controlling reactivity and selectivity of homolytic radical reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202320243 (2024).

Yang, C.-J., Liu, L., Gu, Q.-S. & Liu, X.-Y. Research progress in enantioselective radical desymmetrization reactions. CCS Chem. 6, 1612–1627 (2024).

Bao, X., Rodriguez, J. & Bonne, D. Enantioselective synthesis of atropisomers with multiple stereogenic axes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12623–12634 (2020).

Zhang, Z.-X., Zhai, T.-Y. & Ye, L.-W. Synthesis of axially chiral compounds through catalytic asymmetric reactions of alkynes. Chem. Catal. 1, 1378–1412 (2021).

Cheng, J. K., Xiang, S.-H., Li, S., Ye, L. & Tan, B. Recent advances in catalytic asymmetric construction of atropisomers. Chem. Rev. 121, 4805–4902 (2021).

Cheng, J. K., Xiang, S.-H. & Tan, B. Organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral molecules: development of strategies and skeletons. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2920–2937 (2022).

Qin, W., Liu, Y. & Yan, H. Enantioselective synthesis of atropisomers via vinylidene ortho-quinone methides (VQMs). Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2780–2795 (2022).

Mei, G.-J., Koay, W. L., Guan, C.-Y. & Lu, Y. Atropisomers beyond the C–C axial chirality: advances in catalytic asymmetric synthesis. Chem. 8, 1855–1893 (2022).

Zhang, H.-H. & Shi, F. Organocatalytic atroposelective synthesis of indole derivatives bearing axial chirality: strategies and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2562–2580 (2022).

Qian, P.-F., Zhou, T. & Shi, B.-F. Transition-metal-catalyzed atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral styrenes. Chem. Commun. 59, 12669–12684 (2023).

Xiang, S.-H., Ding, W.-Y., Wang, Y.-B. & Tan, B. Catalytic atroposelective synthesis. Nat. Catal. 7, 483–498 (2024).

Zheng, S.-C. et al. Organocatalytic atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral styrenes. Nat. Commun. 8, 15238 (2017).

Jia, S. et al. Organocatalytic enantioselective construction of axially chiral sulfone-containing styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7056–7060 (2018).

Wang, Y.-B. et al. Rational design, enantioselective synthesis and catalytic applications of axially chiral EBINOLs. Nat. Catal. 2, 504–513 (2019).

Jin, L. et al. Atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral styrenes via an asymmetric C–H functionalization strategy. Chem. 6, 497–511 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Tandem iridium catalysis as a general strategy for atroposelective construction of axially chiral styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 10686–10694 (2021).

Wu, S. et al. Urea group-directed organocatalytic asymmetric versatile dihalogenation of alkenes and alkynes. Nat. Catal. 4, 692–702 (2021).

Ji, D. et al. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrophosphination of internal alkynes: Atroposelective access to phosphine-functionalized olefins. Chem 8, 3346–3362 (2022).

Yan, J.-L. et al. Carbene-catalyzed atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral styrenes. Nat. Commun. 13, 84 (2022).

Guo, F., Fang, S., He, J., Su, Z. & Wang, T. Enantioselective organocatalytic synthesis of axially chiral aldehyde-containing styrenes via SNAr reaction-guided dynamic kinetic resolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 5050 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Synthesis of axially chiral alkenylboronates through combined copper- and palladium-catalysed atroposelective arylboration of alkynes. Nat. Synth. 2, 140–151 (2023).

Sheng, F.-T. et al. Control of axial chirality through NiH-catalyzed atroposelective hydrofunctionalization of alkynes. ACS Catal. 13, 3841–3846 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Ni-catalysed assembly of axially chiral alkenes from alkynyl tetracoordinate borons via 1,3-metallate shift. Nat. Chem. 16, 42–53 (2024).

Wu, F., Zhang, Y., Zhu, R. & Huang, Y. Discovery and synthesis of atropisomerically chiral acyl-substituted stable vinyl sulfoxonium ylides. Nat. Chem. 16, 132–139 (2024).

Wu, Q.-H. et al. Organocatalytic olefin C–H functionalization for enantioselective synthesis of atropisomeric 1,3-dienes. Nat. Catal. 7, 185–194 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Access to axially chiral styrenes via a photoinduced asymmetric radical reaction involving a sulfur dioxide insertion. Chem. Catal. 2, 164–177 (2022).

Li, Q.-Z., Li, Z.-H., Kang, J.-C., Ding, T.-M. & Zhang, S.-Y. Ni-catalyzed, enantioselective three-component radical relayed reductive coupling of alkynes: Synthesis of axially chiral styrenes. Chem. Catal. 2, 3185–3195 (2022).

Wang, X., Ding, Q., Yang, C., Yang, J. & Wu, J. Enantioselective sulfonylation using sodium hydrogen sulfite, 4-substituted Hantzsch esters and 1-(arylethynyl)naphthalen-2-ols. Org. Chem. Front. 10, 92–98 (2023).

Lin, Z., Hu, W., Zhang, L. & Wang, C. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric cross-electrophile trans-aryl-benzylation of α-naphthyl propargylic alcohols. ACS Catal. 13, 6795–6803 (2023).

Fu, L., Chen, X., Fan, W., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric functionalization of vinyl radicals for the access to vinylarene atropisomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13476–13483 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Huo, L., Zhao, X. & Chu, L. Atroposelective three-component (fluoro)methylative alkylation of terminal alkynes. ACS Catal. 15, 63–71 (2025).

Tang, J.-B. et al. Synthesis of axially chiral vinyl halides via Cu(I)-catalyzed enantioselective radical 1,2-halofunctionalization of terminal alkynes. ACS Catal. 15, 502–513 (2025).

Glaser, C. Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Acetenylbenzols. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 2, 422–424 (1869).

Kamata, K., Yamaguchi, S., Kotani, M., Yamaguchi, K. & Mizuno, N. Efficient oxidative alkyne homocoupling catalyzed by a monomeric dicopper‐substituted silicotungstate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 2407–2410 (2008).

Bakhoda, A. et al. Three-coordinate copper(II) alkynyl complex in C–C bond formation: the sesquicentennial of the Glaser coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18483–18490 (2020).

Nakamura, K. & Nishikata, T. Tandem reactions enable trans- and cis-hydro-tertiary-alkylations catalyzed by a copper salt. ACS Catal. 7, 1049–1052 (2017).

Xu, T. & Hu, X. Copper‐catalyzed 1,2‐addition of α‐carbonyl iodides to alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1307–1311 (2015).

Wu, D., Fan, W., Wu, L., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective radical chlorination of alkenes. ACS Catal. 12, 5284–5291 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. Regio- and enantioselective hydrofluorination of internal alkenes via nickel-catalyzed hydrogen atom transfer. Chin.Chem. Lett. 36, 110239 (2024).

Yamane, Y., Miwa, N. & Nishikata, T. Copper-catalyzed functionalized tertiary-alkylative Sonogashira type couplings via copper acetylide at room temperature. ACS Catal. 7, 6872–6876 (2017).

Dong, X.-Y. et al. A general asymmetric copper-catalysed Sonogashira C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling. Nat. Chem. 11, 1158–1166 (2019).

Wang, F.-L. et al. Mechanism-based ligand design for copper-catalysed enantioconvergent C(sp3)–C(sp) cross-coupling of tertiary electrophiles with alkynes. Nat. Chem. 14, 949–957 (2022).

Foxall, J. et al. Radical addition to alkynes: electron spin resonance studies of the formation and reactions of vinyl radicals. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 273–278 (1980).

Rubin, H. & Fischer, H. The addition of tert‐butyl (Me3Ċ) and (tert‐butoxy)carbonylmethyl (Me3CO2CĊH2) radicals to alkynes in solution studied by ESR spectroscopy. Helv. Chim. Acta 79, 1670–1682 (1996).

Wille, U. Radical cascades initiated by intermolecular radical addition to alkynes and related triple bond systems. Chem. Rev. 113, 813–853 (2013).

Parsaee, F. et al. Radical philicity and its role in selective organic transformations. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 486–499 (2021).

Garwood, J. J. A., Chen, A. D. & Nagib, D. A. Radical polarity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 28034–28059 (2024).

Dong, X.-Y., Li, Z.-L., Gu, Q.-S. & Liu, X.-Y. Ligand development for copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical cross-coupling of racemic alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17319–17329 (2022).

Dong, X.-Y. et al. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric radical 1,2-carboalkynylation of alkenes with alkyl halides and terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9501–9509 (2020).

Cheng, Y.-F. et al. Cu-catalysed enantioselective radical heteroatomic S–O cross-coupling. Nat. Chem. 15, 395–404 (2023).

Chen, J.-J. et al. Enantioconvergent Cu-catalysed N-alkylation of aliphatic amines. Nature 618, 294–300 (2023).

Tian, Y. et al. A general copper-catalysed enantioconvergent C(sp3)–S cross-coupling via biomimetic radical homolytic substitution. Nat. Chem. 16, 466–475 (2024).

Gao, Z. et al. Copper-catalysed synthesis of chiral alkynyl cyclopropanes using enantioconvergent radical cross-coupling of cyclopropyl halides with terminal alkynes. Nat. Synth. 4, 84–96 (2025).

Wang, L.-L. et al. A general copper-catalysed enantioconvergent radical Michaelis–Becker-type C(sp3)–P cross-coupling. Nat. Synth. 2, 430–438 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Copper‐catalyzed chemo‐ and enantioselective radical 1,2‐carbophosphonylation of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218523 (2023).

Wang, F. L. et al. Synthesis of α‐quaternary β‐lactams via copper‐catalyzed enantioconvergent radical C(sp3)−C(sp2) cross‐coupling with organoboronate esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214709 (2023).

Sladojevich, F., Trabocchi, A., Guarna, A. & Dixon, D. J. A new family of cinchona-derived amino phosphine precatalysts: application to the highly enantio- and diastereoselective silver-catalyzed isocyanoacetate aldol reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1710–1713 (2011).

Telfer, S. G. & Kuroda, R. 1,1′-Binaphthyl-2,2′-diol and 2,2′-diamino-1,1′-binaphthyl: versatile frameworks for chiral ligands in coordination and metallosupramolecular chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 242, 33–46 (2003).

Tan, B. Axially Chiral Compounds: Asymmetric Synthesis And Applications (Wiley, 2021).

Ma, C. et al. Atroposelective access to oxindole-based axially chiral styrenes via the strategy of catalytic kinetic resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15686–15696 (2020).

Liu, S.-J. et al. Rational design of axially chiral styrene‐based organocatalysts and their application in catalytic asymmetric (2+4) cyclizations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202112226 (2022).

Chen, Z.-B. et al. An axially chiral styrene–phosphine ligand for Pd-catalyzed asymmetric N-alkylation of indoles. J. Org. Chem. 88, 14719–14727 (2023).

Hao, Y. et al. Axially chiral styrene-based organocatalysts and their application in asymmetric cascade Michael/cyclization reaction. Chem. Sci. 14, 9496–9502 (2023).

Yang, J., Xiao, J., Chen, T. & Han, L.-B. Nickel-catalyzed phosphorylation of aryl triflates with P(O)H compounds. J. Organomet. Chem. 820, 120–124 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Asymmetric azide–alkyne cycloaddition with Ir(I)/squaramide cooperative catalysis: atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral aryltriazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6200–6207 (2022).

Patel, N. D. et al. Computationally assisted mechanistic investigation and development of Pd-catalyzed asymmetric Suzuki–Miyaura and Negishi cross-coupling reactions for tetra-ortho-substituted biaryl synthesis. ACS Catal. 8, 10190–10209 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22025103, 92256301, 22331006, to X.-Y.L.; 22201125, to P.-F.W.), the National Key R&D Program of China (Nos. 2021YFF0701604, to X.-Y.L.), Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (No. 2023B0303000020, to X.-Y.L.), New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE (to X.-Y.L.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Nos. KQTD20210811090112004, to X.-Y.L. and Q.-S.G.; JCYJ20220818100600001, to X.-Y.L.; JCYJ20220818100604009, to J.-B.T.), the Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Cross-Coupling Reactions (No. ZDSYS20220328104200001 to X.-Y.L.), High-Level of Special Funds (No. G03050K003, to X.-Y.L.), and High-Level Key Discipline Construction Project (No. G030210001, to X.-Y.L. and Q.-S.G.) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors acknowledge the assistance of SUSTech Core Research Facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-Q.B. and J.-B.T. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.-Q.B., L.Q., L.-W.F., J.F., Y.-F.C., Y.-F.Z., P.-F.W. and J.-B.T. performed the experiments. Q.S., Z.-L.L., Q.-S.G., P.Y., J.-B.T. and X.-Y.L. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript. J.-B.T. and X.-Y.L. conceived and supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bo Zhou and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, JQ., Qin, L., Fan, LW. et al. Cu(I)-catalysed chemo-, regio-, and stereoselective radical 1,2-carboalkynylation with two different terminal alkynes. Nat Commun 16, 4922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60012-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60012-z