Abstract

Acute myocardial infarction has been the second leading cause of death in Taiwan. It’s a novel issue to evaluate the relationship between the 24-h PCI service model and the outcome of STEMI patients. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of 24-h PCI service model in STEMI patients to improving survival rate. This population-based cohort study included those STEMI patients, older than 18 year-old, who had ever called emergency department from 2012 to 2018. We had two groups of our study participant, one group for STEMI patients with 24-h PCI model and the other group for STEMI patients with non-24-h PCI model. We used the Logistic regression model to analyze the risk of death within 30 days, emergency department (ED) revisits within 3 days, and readmission within 14 days. After the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of death after an ED visit among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was significantly lower than that among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI services (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.75–0.98). However, the model could not reduce the risk of ER revisits and readmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is the second leading cause of death in Taiwan. In 2021, the death toll due to AMI reached 21,852, and an average death toll was 45.6 per 100,000 people1. In the United States, approximately 550,000 patients are newly diagnosed with myocardial infarction (MI) each year, and approximately 200,000 patients experience the recurrence of MI2. A 2017 study recommended that patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) should be treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 90 min after arriving at the emergency department of a hospital that can perform 24-h PCI.

A hospital revisit that occurs shortly after an emergency department visit (usually defined as a visit made within 72 h [3 days]) is referred to as an early return visit. The early return rate is regarded as a key indicator of the quality of emergency care3,4,5,6. Studies have reported that patients who made early return visits had a higher mortality rate6 and higher risk of being involved in medical disputes4. A Taiwanese study indicated that the rate of emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge was approximately 5.47% and that the major reason for revisits was disease-related factors (80.9%), followed by patient-related factors (10.9%), and then doctor-related factors (8.2%)7. Therefore, the rate of hospital revisits within 3 days after discharge is a key indicator of the quality of emergency care, and it also affects patient prognosis and subsequent medical cost.

According to U.S. statistics pertaining to the period from 2010 to 2014, the rate of hospital readmission within 30 days after discharge among patients with STEMI was 12.3%8. Another large-scale, nationwide U.S. study revealed that 10.3% of patients with STEMI who had multiple coronary arteries unblocked were hospitalized again within 30 days after discharge, and within this subgroup of patients with STEMI, 62.66% were hospitalized because of cardiac factors9. Furthermore, women, patients with a family history of coronary artery disease, patients with a low family income, and patients who were treated in hospitals located in highly urbanized areas or nonteaching hospitals were reported to have a significantly higher rate of hospital readmission within 30 days after discharge relative to other groups of patients8. Patients with STEMI who were readmitted within 30 days after their emergency department visits were verified to have a significantly higher mortality rate (increase of 42%)10.

At present, not all hospitals in Taiwan provide 24-h PCI services. The PCI services in Taiwan can be divided into two models, namely the 24-h PCI service model and the non-24-h PCI service model. In the present study, we explored whether these models significantly affect patients with STEMI in terms of their risk of death within 30 days after emergency department visits, emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge, and readmissions within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department.

Results

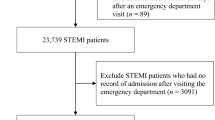

Overall, 27,219 patients with STEMI were initially included; however, 231 patients aged less than 18 years, 3160 who had been diagnosed with STEMI, 89 who died of accidents, and 3091 who were not hospitalized (patients with STEMI should be hospitalized in Taiwan) were excluded. Eventually, 20,648 patients with STEMI were selected as participants.

After a chi-square test was conducted, a bivariate analysis was performed to determine whether patients with STEMI died within 30 days after their emergency department visits, the patients with STEMI revisited the emergency department within 3 days after they were discharged from an emergency department, and the patients with STEMI were readmitted within 14 days after their discharge from an emergency department. Table 1 reveals that 2281 patients with STEMI (11.05%) died within 30 days after an emergency department visit; among the patients who were sent to hospitals with a 24-h PCI service model, the mortality rate within 30 days after an emergency department visit was 7.71%, which was lower than that of patients who were sent to hospitals without a 24-h PCI service model (12.12%; P < 0.05). Table 1 also reveals that 234 patients with STEMI (1.13%) revisited an emergency department within 3 days after discharge. The rate of emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge among the patients who were sent to hospitals with a 24-h PCI service model was 0.58%, which was significantly lower than that among the patients who were sent to hospitals without a 24-h PCI service model (1.31%; P < 0.05). Table 1 reveals that 246 patients with STEMI (1.19%) were readmitted within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department. Among the patients who were treated in hospitals with a 24-h PCI service model, the rate of readmission within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department was 0.92%, which was significantly lower than that among the patients who were treated in hospitals without a 24-h PCI service model (1.28%; P < 0.05).

A logistic regression model that applied GEEs was employed to estimate the effect of the 24-h PCI service model on the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit among the patients with STEMI. Table 2 indicates that after the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of death among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was significantly lower (lower by 15%) relative to that of the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI services (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.75–0.98; P < 0.05).

After the analysis of the logistic regression model that applied GEEs was completed, the effect of the 24-h PCI service model on the risk of emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge among the patients with STEMI was explored. Table 3 reveals that after the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was lower than that among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI services. However, the difference was nonsignificant (OR 0.73; 95% CI 0.48–1.10; P > 0.05).

After the analysis of the logistic regression model that applied GEEs was completed, the effect of the 24-h PCI service model on the risk of readmission within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department among the patients with STEMI was estimated. Table 4 reveals that after the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of readmission within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was lower than that among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI services. Nevertheless, the difference was nonsignificant (OR 0.87; 95% CI 0.62–1.22; P > 0.05). Furthermore, we conducted an analysis, as shown in Supplementary Table S1, that only focused on STEMI patients with PCI to compare the differences between hospitals providing 24-h PCI services or not. After the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of death after an ED visit among the patients with STEMI undergoing PCI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was significantly lower than that among the patients with STEMI undergoing PCI who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI services (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.71–0.97). Among STEMI patients with PCI, a similar result was obtained.

Discussion

After the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of death among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was significnately lower than that among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hostpials without 24-h PCI services. A reason may be that most hospitals that provided 24-h PCI services in Taiwan were medical centers or regional hospitals. We also discovered that for hospital level, the risk of death among the patients who were sent to district hospitals was significantly higher than that among the patients who were sent to medical centers. Furthermore, the patients who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services were less prone to undergoing delayed PCI treatment because of referrals. Studies have revealed that the risk of death among patients with AMI is significantly correlated with the time between the onset of AMI and the unblocking of vessels during PCI (i.e., ischemic time) and the time between arrival at an emergency room and the unblocking of vessels during PCI (D2B or D2W).11,12,13.

We discovered that the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency visit was significantly lower among the patients with STEMI who were sent to medical centers than among those who were sent to other types of hospitals. A reason may be that, relative to other types of hospitals, medical centers typically exhibited greater compliance with the clinical guidelines for patients with STEMI. Literature findings indicate that hospitals that exhibit greater compliance with clinical guidelines contribute to a significantly lower risk of death among patients.14 We also discovered that the patients who underwent PCI had a significantly lower risk of death relative to those who did not undergo PCI. In Taiwan, patients with STEMI who cannot undergo PCI are either referred to other hospitals or treated with fibrinolytic therapy. Some patients were not suitable for PCI because of their highly critical condition (occlusion of all three coronary arteries). A study reported that the risk of death among patients with AMI who underwent PCI directly is lower than that among patients who underwent fibrinolytic therapy.15 In addition, if a patient is referred to another hospital because they cannot undergo PCI at the first hospital that they were admitted to, their PCI treatment is delayed, which further affects their prognosis.16,17 The three aforementioned conditions are likely to significantly reduce the risk of death among patients who undergo PCI.

However, the 24-h PCI service model could not reduce the risk of an emergency department revisit within 3 days after discharge and the risk of readmission within 14 days after discharge. With the implementation of the National Health Insurance program, accessibility to medical care became high in Taiwan. Patients with STEMI who are likely to undergo full treatment and be discharged in a stable condition are treated through conventional procedures. This is demonstrated by the low rates of emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge (1.13%) and the low rates of readmission within 14 days after discharge (1.19%) (Table 1).

Accordingly, we recommend a reasonable expansion of the 24-h PCI service model. The results indicate that the 24-h PCI service model significantly reduced the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency visit among patients with STEMI. Thus, the government should establish the 24-h PCI service model in all administrative districts to reduce the risk of death among patients with STEMI.

There are several strengths in the present study. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance program provides insurance coverage to approximately 99.9% of its citizens. Therefore, the data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided a sufficient representation of Taiwan’s population. National, full-population, and multiyear data were applied in the present study; hence, the statistics were reliable. In addition, the factors that can affect the prognosis of patients with STEMI (e.g., risk of death, risk of revisiting the emergency department within 3 days after discharge, and risk of readmission within 14 days after discharge) were comprehensively explored in the present study. The present study also has several limitations. We performed a retrospective analysis by using secondary data obtained from the National Health Insurance Research Database. Because of the data constraints of the database, we could not study the health behaviors, the timing of their cardiac catheterization procedures, and the admission time of the participants. This was a limitation of the present study. Although Taiwan's National Health Insurance coverage is extensive, economic considerations may still be a primary factor in healthcare treatment. Despite medical guidelines’ recommendations, it is still true that not every patient with PCI received drug-eluting stent implantation because Taiwan’s NHI only partially covered the cost of drug-eluting stents. In future research, we also suggest further analyzing the impact of other factors, such as CABG, drug-eluting stents, and medication such as ACEI/ARB, antiplatelet agents, and beta-blockers.

Conclusions

After the relevant variables were controlled, the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services was significantly lower than that among the patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI services (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.75–0.98). Therefore, the establishment of the 24-h PCI service model significantly reduced the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit among the patients with STEMI. However, the model could not reduce the risk of emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge and the risk of readmission within 14 days after discharge.

Material and methods

Data sources

The data analyzed in the present study were secondary data. Data for the period from 2010 to 2018 were retrieved from the National Health Insurance Research Database for analysis. We collected data pertaining to the claims of outpatients, emergency patients, and inpatients; death cause statistics; and major illness. These data were compiled, and those that corresponded to the relevant variables were selected for analysis. Since the patient identifications in the National Health Insurance Research Database have been scrambled random identification numbers for insured patients by the Taiwan government for academic research use, the informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Committee of the Taichung Jen-Ai Hospital. The research was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and amendments and was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Taichung Jen-Ai Hospital (IRB NO. 111-20), Taiwan.

Study participants

We enrolled patients with STEMI who visited an emergency department between 2012 and 2018, and we analyzed whether the provision of 24-h PCI service affected the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit, emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge, and readmission within 14 days after discharge of patients with STEMI. Patients with STEMI who visited emergency departments were enrolled as participants; however, patients were excluded if they were aged less than 18 years, had been diagnosed with MI, committed suicide or died of an accident within 30 days after an emergency department visit, or had no record of admission or death after an emergency department visit. The emergency department visits were defined as medical behaviors that corresponded to the billing codes 00201B, 00202B, 00203B, 00204B, and 00225B. A diagnosis of STEMI was defined as a diagnosis made with the following codes: 410.0X–410.6X and 410.8X of ICD-9-CM or I21.01, I21.02, I21.09, I21.11, I21.19, I21.21, I21.29, I22.0, I22.1, I22.8, and I22.9 of ICD-10-CM. Figure 1 was the flow chart of study participants.

Definition and description of variables

The definition of the variables considered in the present study are as follows. Twenty-four-hour PCI service was defined as a treatment performed in a hospital that provided 24-h PCI. A patient with STEMI was defined as a patient who was diagnosed with STEMI in accordance with the following principle discharge diagnosis codes: 410.0X–410.6X and 410.8X of ICD-9-CM or I21.01, I21.02, I21.09, I21.11, I21.19, I21.21, I21.29, I22.0, I22.1, I22.8, and I22.9 of ICD-10-CM. The gender of the patients was either male or female. The patients were divided into the following age groups: < 45 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and ≥ 85 years. For monthly salary, the patients were divided into the following groups: ≤ NT$17 280, NT$17 281–NT$22 080, NT$22 081–NT$36 300, and ≥ NT$36 301. The urbanization levels of the patients’ residential areas were divided into Levels 1–7; Levels 1 and 7 indicated the highest and lowest levels of urbanization, respectively18. The hospitals investigated in the present study were classified as medical centers regional hospitals, and district hospitals. In Taiwan, hospitals are categorized into medical centers, regional hospitals, and district hospitals based on the results of hospital accreditation. Hospital accreditation includes many dimensions, such as the healthcare workforce, medical services provided, medical education, medical research, quality of medical care, etc. On the basis of ownership, the hospitals were classified as public and nonpublic hospitals. The comorbidity severity was estimated using Deyo’s Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Deyo’s CCI is a modified version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and it classifies comorbidities into 17 types. The principal and secondary diagnosis codes of the patients were converted into weighted scores, which were then summed to calculate Deyo’s CCI scores19. The comorbidity severity was rated on a scale from 0 to 4 points. Classification of major illness comprised the presence (yes) and absence (no) of any major illness. The applied triage categories were Level 1 (Code 00201B), Level 2 (Code 00202B), Level 3 (Code 00203B), Level 4 (Code 00204B), and Level 5 (Code 00225B); Level 1 patients were those who most urgently required medical attention. Administration of PCI referred to patients who underwent PCI (codes 33076B, 33077B, and 33078B) during emergency visits or hospitalization.

Quantitation of major results

In the present study, we primarily explored whether the 24-h PCI service model affected patients with STEMI with respect to their risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit, their emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge, and their readmission within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department.

Statistical analysis

The present study adopted a retrospective cohort design. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was employed for secondary data processing and statistical analysis.

For descriptive statistics, the results pertaining to the following variables were expressed as percentages: age, gender, monthly salary, level of urbanization of residential area, severity of comorbidity (CCI), presence or absence of major illness, emergency triage level, performance of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), MI severity, death within 30 days after an emergency department visit, emergency department revisit within 3 days after discharge, readmission within 14 days after discharge, 24-h PCI capability of hospital, hospital level, and hospital ownership.

Inferential statistics were used to determine whether the 24-h PCI service model affected patients with STEMI in terms of risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit, emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge, and readmission within 14 days after discharge from an emergency department. A chi-square test was first performed to analyze the differences between patients with MI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services and those who were sent to hospitals without 24-h PCI service in terms of mortality rate within 30 days after an emergency department visit, emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge, and readmission within 14 days after discharge. Subsequently, a logistic regression model that employed generalized estimating equations (GEEs) was applied to compare differences between patients with STEMI who were sent to hospitals with 24-h PCI services and those who were sent to hospital without 24-h PCI services regarding the risk of death within 30 days after an emergency department visit, emergency department revisits within 3 days after discharge, and readmission within 14 days after discharge while controlling for other factors (i.e., gender, age, monthly salary, level of urbanization of residential area, CCI, presence or absence of major illness, hospital level, hospital ownership, and triage level). Besides, we conducted an analysis that only focused on STEMI patients with PCI to compare the differences between hospitals providing 24-h PCI services or not.

Data availability

The National Health Insurance Database used to support the findings of this study were provided by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare (HWDC, MOHW) under license and so cannot be made freely available. Requests for access to these data should be made to HWDC (https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/dos/np-2497-113.html).

References

Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan. 2021 Cause of Death Statistics. Accessed at https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/lp-5069-113-xCat-y110.html. Accessed on 20-Feb-2023.

Anderson, J. L. & Morrow, D. A. Acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2053–2064 (2017).

Easter, J. S. & Bachur, R. Physicians’ assessment of pediatric returns to the emergency department. J. Emerg. Med. 44, 682–688 (2013).

Liaw, S. J., Bullard, M. J., Hu, P., Chen, J.-C. & Liao, H.-C. Rates and causes of emergency department revisits within 72 hours. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. Taiwan yi zhi 98, 422–425 (1999).

Goh, S., Masayu, M., Teo, P., Tham, A. & Low, B. Unplanned returns to the accident and emergency department–why do they come back?. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 25, 541–546 (1996).

Safwenberg, U., Terént, A. & Lind, L. Increased long-term mortality in patients with repeated visits to the emergency department. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 17, 274–279 (2010).

Wu, C.-L. et al. Unplanned emergency department revisits within 72 hours to a secondary teaching referral hospital in Taiwan. J. Emerg. Med. 38, 512–517 (2010).

Kim, L. K. et al. Thirty-day readmission rates, timing, causes, and costs after ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction in the United States: a national readmission database analysis 2010–2014. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e009863 (2018).

Tripathi, B. et al. Etiologies, trends, and predictors of readmission in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 94, 905–914 (2019).

Moreyra, A. E., Deng, Y., Cogrove, N. M., Pantazopoulos, J. S. & Kostis, J. B. for the MIDAS study group. Readmission rates for acute coronary syndrome and mortality after PCI for STEMI: the influence of socioeconomic status (abstr). Circulation 126, A16579 (2012).

McNamara, R. L. et al. Effect of door-to-balloon time on mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 2180–2186 (2006).

Solhpour, A. et al. Ischemic time is a better predictor than door-to-balloon time for mortality and infarct size in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 87, 1194–1200 (2016).

Park, J. et al. Prognostic implications of door-to-balloon time and onset-to-door time on mortality in patients with ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012188 (2019).

Plakht, Y., Greenberg, D., Gilutz, H., Arbelle, J. E. & Shiyovich, A. Mortality and healthcare resource utilization following acute myocardial infarction according to adherence to recommended medical therapy guidelines. Health Policy 124, 1200–1208 (2020).

Henriques, J. et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention versus thrombolytic treatment: long term follow up according to infarct ___location. Heart 92, 75–79 (2006).

Clemmensen, P. et al. Pre-hospital diagnosis and transfer of patients with acute myocardial infarction—A decade long experience from one of Europe’s largest STEMI networks. J. Electrocardiol. 46, 546–552 (2013).

Fosbol, E. L. et al. The impact of a statewide pre-hospital STEMI strategy to bypass hospitals without percutaneous coronary intervention capability on treatment times. Circulation 127, 604–612 (2013).

Chieh-Yu Liu, Y.-T.H. et al. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J. Health Manag. 4(1), 1–22 (2006).

Deyo, R. A., Cherkin, D. C. & Ciol, M. A. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol 45, 613–619 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful for the use of the database provided by the Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. We are grateful to Health Data Science Center, China Medical University Hospital for providing administrative, technical and funding.

Funding

This study is partly supported by China Medical University and Asia University (CMU111-ASIA-14). Funders had no role in the development or publication of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-H.T., P.-T.K., and W.-C.T.; formal analysis, S.-M.W. and T.-H.T.; funding acquisition, W.-C.T.; investigation, P.-T.K. and W.-C.T.; methodology, C.-H.T., P.-T.K., and W.-C.T.; validation, P.-T.K. and W.-C.T.; writing—original draft, C.-H.T., P.-T.K., and W.-C.T.; writing—review and editing, W.-C.T.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, CH., Kung, PT., Wang, SM. et al. 24-h PCI model does affect the outcome of STEMI patients: a population-based study. Sci Rep 13, 13063 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40276-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40276-5