Abstract

Oral-drug based regimens are useful in certain circumstances for transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (TI-NDMM), but few studies have compared Ixazomib based regimen with lenalidomide based regimen head-to-head. We carried out a prospective randomized, open, parallel group trial in patients with TI-NDMM in 3 China centers from March 2020 to December 2022. Sixty-three patients were available for final analysis, ICd (Ixazomib/cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone, n = 31) and RCd (lenalidomide/cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone, n = 32). The primary objective was to compare the two regimens by analyzing the overall response rate (ORR), safety profiles, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). We also explored clinical and the biological characteristics of the patients with primary drug resistance. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between ICd and RCd groups, with the median age 70 vs. 70 years; 12.9% vs. 12.5% of patients had stage III disease; 25.8% vs. 28.1% had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities. The overall response rate (ORR) at the end of 4 cycles was 87.1% vs. 71.9% (odds ratio [OR], 1.212; 95% CI, 0.938–1.565; P = 0.213); the best ≥ VGPR rate was 41.9% vs. 31.2% (OR, 1.342; 95% CI 0.694–2.597; P = 0.439). Among high-risk cytogenetic patients, ORR was higher in the ICd group, 75% vs. 55.5% (P = 0.620), respectively. After 35 months follow-up, the median PFS were 22 and 23 months between ICd and RCd groups (P = 0.897). Median OS was not reached, estimated 3-year OS rate was 86.4% vs. 85.4% (P = 0.774). The most common adverse events of grade 3 or 4 were neutropenia (6.5% in the ICd group vs. 31.3% in the RCd group), anemia (19.4% vs. 18.8%), pneumonia (0 vs. 15.6%) and diarrhea (12.9% vs. 0). Treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) induced dose reduction and discontinuation were 22.6% vs. 37.5% and 3.2% vs. 6.3% in the ICd vs. RCd group, respectively. Exploration data showed that patients with t (4;14) were insensitive to initial RCd treatment. The ICd regimen showed a tendency towards improved ORR compared to RCd regimen. Both ICd and RCd regimens demonstrated less dose reduction and treatment discontinuation, suggesting their tolerability and feasibility for older individuals with TI-NDMM.

Trial registration: This study was registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Register (ChiCTR). Trial registration number: ChiCTR2000029863. Date of registration: 15/02/2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs) and/or immunomodulators combined with other drugs of different mechanisms are the standards of care for transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (TI-NDMM) patients, of which bortezomib combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRd) is the most widely recommended and applied1,2. But a real-world study of TI-NDMM patients treated with VRd showed that the median duration of therapy was only 5.5 months, median PFS were 26.5, which was notably shorter than that observed in the clinical trials3.

It’s undeniable that bortezomib significantly improves survival in myeloma patients, but neurotoxicity and frequent hospital trips, reduce tolerance in older patients and affect long-term administration and effectiveness. An increased focus on continuous therapy4,5has heightened the need for regimens that have acceptable side-effect profiles and that are easy to administer. Ixazomib is an oral PI with low neurotoxicity and amenable to weekly administration. TOURMALINE-MM2 demonstrates that ixazomib-Rd (IRd) is a feasible all-oral treatment option for TI-NDMM, more than half the patients completed the initial 18 cycles therapy. In contrast, in SWOG S0777, only 55.7% of patients received VRd for the protocol-specified maximum of 8 cycles6,7 However, as a regimen for continuous therapy, especially for elderly myeloma patients, IRd was not the best and only option. The safety data showed the Treatment Emergent Adverse Events (TEAEs) resulting in dose discontinuation of the full study drug was 35%, grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia and pneumonia were 13.3% and 10.9%.

In practice, there were still alternative oral-drug based induction treatment options for TI-NDMM, especially when face to the economic burden, treatment tolerability concerns, and health insurance limitations (lenalidomide and ixazomib cannot be covered by insurance at the same time in China). Sometimes a three-drug combination regimen consisting of only one new drug combined with an alkylating agent is used, such as RCd8,9(lenalidomide/cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone) or ICd10,11 (Ixazomib/cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone).

To date, there was no relevant studies to clarify whether RCd or ICd is more suitable for TI-NDMM as a first line of therapy. We therefore conducted a randomized, controlled, open, parallel group, multi-center clinical trial of RCd compared to ICd in elderly NDMM patients who were not eligible for transplantation, to determine the efficacy and safety of RCd and ICd. Meanwhile we expect to explore the clinical and biological characteristics of patients with primary insensitivity to Ixazomib or Lenalidomide based therapy.

Methods

It was conducted by Hematology Department, Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and enrolling patients from 3 sites in China between March 2020 to December 2022. The study was approved by Ruijin hospital’s Clinical Research and animal Ethics Committee and registered at the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (ChiCTR200002986). The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Hgrouponization of Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was collected for all participants.

Patients

The study enrolled patients, who were ineligible to the auto stem cell transplantation due to age ≥ 65 years, with newly diagnosed MM fulfilling the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG)12 criteria for symptomatic MM. Patients were required to have measurable disease (serum M-protein ≥ 1 g/dL or urine M-protein ≥ 200 mg/24 h or involved free light chain level ≥ 10 mg/dL provided the serum free light chain ratio was abnormal). Eastern Cooperative Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) 0–2, adequate hematologic (absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1000/mm3, platelets ≥ 50,000/mm3), hepatic (total bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × upper limit of normal [ULN], alanine/aspartate aminotransferase ≤ 3 × ULN), and creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≥ 30 mL/min. Patients with high-risk genetics was defined by one of the following abnormalities on FISH testing: t (4;14), t (14;16), t (14;20) or del17p. Patients with plasma cell leukemia, amyloidosis, and POEMS syndrome were excluded.

Intervention

Induction therapy was defined as 8 cycles of three-drug combination (each cycle of 4 weeks). Patients in the RCd group received lenalidomide 25 mg for CrCl ≥ 60 ml/min and 10 mg for CrCl 30–60 ml/min, orally on days 1–21, with cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2 IV drip on day 1 and dexamethasone 40 mg orally on days 1–4. Patients in the ICd group received lxazomib 4 mg orally on days 1, 8 and 15, with the same dose cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone as above. For age ≥ 75, the starting dose of dexamethasone reduced to 20 mg. The maintenance regimens were Rd (R, 10 mg orally on days 1–21; D, 10 mg orally on days 1–4) in the RCd group and Id (I, 4 mg orally on day 1, 8, 15; and D, 10 mg orally on days 1–4) in the ICd group every 4 weeks. Participants received treatment until disease progression, intolerance, or consent withdrawal. If at least partial response (PR) was not reached after 4 cycles, patients went off study and were permitted to crossover group (from RCd to ICd, vice versa) or receive alternative treatment. Aspirin prophylaxis (75 ~ 100 mg oral daily) was given in RCd group. All patients received antiviral therapy (acyclovir 400 mg twice daily) for prevention of herpes zoster and were allowed to receive bisphosphonates and other supportive care as needed.

Assessments

Myeloma disease response was defined according to the 2016 IMWG response criteria13. Disease assessments included serum and 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis, immunofixation, serum free light chain was performed after every cycle during the induction phase and every three cycles during the maintenance phase. Bone marrow examination was performed after 4 cycles and 8 cycles and for documentation of a complete response. Safety and toxicity data were graded using the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0 (NCI CTCAE v 4.0).

Statistical analyses

The primary endpoint was to compare overall response rate (ORR) and safety profiles. The secondary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS). In the statistical analyses of PFS, patients who achieved less than PR after 4 cycles treatment, proceeding to alternative therapy prior to progression considered as censored. Student’s t-tests or the Mann-Whitney test were used to compare the numerical variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The Kaplan–Meier curves were used for survival analysis, and differences were analyzed using the log-rank test. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Safety, toxicity and treatment compliance were summarized descriptively. Analysis was performed using SPSS software version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

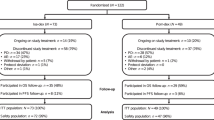

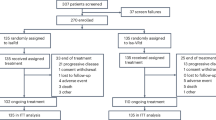

Between March 2020 and December 2022, 63 participants from 3 China hospitals were randomized, ICd group (n = 31) and RCd group (n = 32). Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between two groups (Table 1). Median age was 70 (range, 66–82) vs. 70 (range, 65–77) years; 12.9% vs. 12.5% of patients had stage III disease; 80.6% vs. 93.8% had bone lesion disease; 25.8% vs. 28.1% had high-risk cytogenetics abnormalities in the ICd and RCd groups, respectively.

Response to treatment, progression-free, and overall survival

The overall response rate (ORR) at the end of 4 cycles and best response rate were list in Table 2. At the end of 4 cycles, the ORR were 87.1% vs. 71.9% (OR, 1.212; 95% CI, 0.938–1.565; P = 0.213), with 22.6% vs. 25% achieving ≥ VGPR (OR, 0.903; 95% CI 0.372–2.191; P = 0.822) in the ICd vs. RCd group, respectively. As to the best response, ≥ VGPR rate were 41.9% vs. 31.2% (OR, 1.342; 95% CI 0.694–2.597; P = 0.439); CR rates were 19.3% vs. 15.6% in the ICd vs. RCd group (OR, 1.239; 95% CI 0.421–3.645; P = 0.697), respectively.

Although the samples were small, subgroup analysis showed, 100% ORR were achieved in both ICd (n = 4) and RCd (n = 4) groups in patients aged ≥ 75 years. Among the patients with high-risk cytogenetics (8 patients in the ICd group and 9 patients in the RCd group), the ORR was slightly higher in the ICd group, 75% vs. 55.5% (OR, 1.350; 95% CI, 0.665–2.741; P = 0.620), Fig. 1.

With a median follow-up of 35 (95% CI 30.295–39.705) months, 35.5% (11/31) responders and 25% (8/32) responders were still progression-free in the ICd and RCd groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in the PFS times (22 vs. 23 months) between ICd and RCd group (HR, 1.045; 95% CI 0.533–2.047; P = 0.897, Fig. 2a). The median OS was not reached in either group, 16.1% (5/31) and 15.6% (5/32) patients dying in the ICd and RCd groups, and the estimated 3-year OS rate were 86.4% and 85.4%, respectively (HR, 1.201; 95% CI 0.344–4.194; P = 0.774, Fig. 2b).

Exploratory analysis

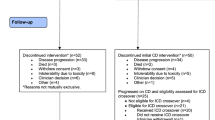

Per protocol, 13 patients went off study for lack of an adequate response (less than PR) after 4 cycles therapy (4 in ICd groups and 9 in RCd groups). We analyzed the clinical data of these patients with primary resistance (Table 3). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data were collected in 6 (2 in ICd and 4 in RCd groups) of the 13 patients. By RNA-seq technology, 2 cases with IgH-NSD2, 1 case with IgH-MYC and 1 case with IgH-MAF were found, which were undetectable by FISH. At data cutoff (May 2024), only one patient died (due to progress disease).

There were 4 patients (MR 2 cases, SD 1 case and PD 1 case) who were not sensitive to the first line ICd therapy. Three patients crossed over to the RCd regimen and achieved PR; one patient with PD (patient #3) was given DPARD (daratumumab/bortezomib/doxorubicin/lenalidomide/dexamethasone) as the second line of therapy and achieved CR. In the RCd group, there were 9 patients who did not achieved at least PR after 4 cycles induction (SD 4 cases, MR 4 cases and PD 1 case). 6 patients cross over to ICd therapy, one of them achieved (patient #7) CR, one patient with t (11;14) remain SD status (patient #12). One patient in PD (patient #13) received DVD (daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone) as the second line of therapy, achieved CR. The second line of treatment regimens and response outcomes were shown in Fig. 3.

Treatment exposure and safety

At the time data frozen (May 2024), 11 (35.5%) and 8 (25.0%) patients were still ongoing on maintenance therapy in the ICd and RCd groups, respectively. Patients received a median of 18 (range, 2–48) cycles and 15 (range, 2–44) cycles of treatment in the ICd and RCd groups. 87.1% vs. 71.9% of patients completed 8 cycles of induction therapy. During induction, the median relative dose intensity (RDI) for all agents were slightly lower in the RCd group (91.4% vs. 96.1%). Dose reductions occurred more frequently in the RCd group than in ICd group (37.5% vs. 22.6%). Treatment discontinuation occurred mostly for disease progression, patients discontinued intervention for TEAEs were 3.2% vs. 6.3% in the ICd vs. RCd group, respectively, (Table 4).

The most common any-grade AEs were neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, constipation, rash and pneumonia (Table 5). Any-grade neutropenia occurred more frequently in the RCd group 26 (81.3%) than in the ICd group 19 (61.3%) (P = 0.080). Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia were reported in 10 (31.3%) patients in the RCd group and in 2 (6.5%) in the ICd group (P = 0.012). Grade 3 or 4 pneumonia occurred in 5 (15.6%) of patients in the RCd group. Fewer patients experienced grade 3 or 4 other nonhematological AEs, except 4 patients (ICd group) reported grade 3 or 4 diarrhea. Both the RCd and the ICd group reported grade 1 or 2 rash, 4 (12.9%) and 5 (15.6%), respectively. Vein thrombosis occurred both in the RCd group with 3 (9.4%) patients and in the ICd group with 2 (6.5%) patients, while all were in grade 1or 2.

Discussion

Although DRD and VRd-lite are currently the mainstream first-line treatment options for TI-NDMM, NCCN guidelines (version 1. 2025) still confirm that options such as RCd8,9and VCd are useful in certain circumstance. Bortezomib is often replaced by ixazomib due to its neurotoxicity and long-term convenience. In some previous studies, ICd10,11 regimen has been confirmed to be feasible for the newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. As an oral based option, it is unclear whether the ICd or the RCd regimen is more appropriate for the elderly transplant ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. The current study is the first trial to compare the efficacy and safety of the RCd and ICd regimes in patients with TI-NDMM head-to-head.

In the present study, it seemed that the ORR of ICd regimen was numerically superior to that of RCd, 87.1% vs. 71.9%, including ≥ VGPR in 41.9% vs. 31.2%. The advantage in ORR of the ICd regimen did not translate into a survival benefit, and there was no statistical difference between the two groups in PFS and OS. The median PFS was 22 vs. 23 months, and the estimated 3-years OS rate was 86.4% vs. 85.4%, respectively. This might be related to the timely replacement regimen for patients who did not achieve PR after initial therapy, and more effective subsequent therapy (such as the regimen containing CD38 monoclonal antibody) for relapsing patients.

In terms of safety, the incidence of 3–4 grade adverse events was low in both groups, at 29% and 31.3%. Neutropenia and pneumonia were more common in the RCd group (31.3% and 15.6%), always leading to dose reductions. However, these rates were still lower than those reported in the MAIA (DRd) study (54% and 19%)14. Grade 3 or 4 diarrhea was reported in the ICd group (12.9%), but not result in discontinuation. Overall, the ICd regimen appeared to be better tolerated than the RCd regimen, with treatment-related dose reductions at 22.6% vs. 37.5% and discontinuations at 3.2% vs. 6.3%, respectively.

These results were consistent with previous studies, with slight differences in efficacy and safety profile that might appear to be affect by the difference of patient age and therapeutic dose. In the phase II study of RCd8, 43% of patients were age>65 years (median 64, range 37–82), an ORR 85% received, including ≥ VGPR in 47%. Patients were given lenalidomide at 25 mg (p. o. D1-21) and CTX (300 mg/m2 D1,8,15). While in the phase 3 trial9, 33% of patients were aged>75 years, lenalidomide was given 10 mg per day for 21 days, oral CTX 50 mg every other day for 21–28 days, the ORR was slightly decrease at 68%. In our RCd group, all the patient were aged ≥ 65 years, including 12.5% ≥ 75 years, lenalidomide was given 25 mg (p. o. D1-21), except 10 mg was received in patients with CrCl 30–60ml/min, CTX was administered intravenously at 750 mg/m2 D1 (reference to the dose in CHOP regimen of lymphoma). Intravenous CTX seemed to be more tolerable in our study, the relative dose intensity (RDI) of CTX were 100% and 96.1% in the ICd group and RCd group. While in a Phase 2 trial of ICd11, 20% of patients occurred AEs resulting in dose reduction of cyclophosphamide, when given 300 mg/m2 or 400 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide orally in D1,8,15.

Although the sample size was small (n= 13), the exploratory analysis of patients with primary resistance (less than PR at the end of 4 cycles) provided some interesting findings and validated some previously reported studies. (a) Combined RNA-seq data allowed more precise identification of the translocation breakpoints than is possible with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). Such as IgH-NSD2, IgH-MYC and IgH-MAF. The next generation sequencing technique should be used to detect more high-risk patients in the future15,16. (b) Patient with IgH-MAF might be insensitive to ixazomib (patient #3). Ya-Wei Qiang17et al. had reported that high expression of MAF protein in myeloma due to t (14;16) translocation confers innate resistance to PIs. And PIs prevent GSK3-mediated degradation of MAF protein, which further augments the resistance to PIs in t (14:16) myeloma. (c) Patient with t (4;14) was insensitive to RCd but sensitive to ICd (patient #7, #8, #9). t (4;14) translocation results in the generation of 2 derivative chromosomes that place fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) and nuclear receptor SET ___domain protein 2 (NSD2) under the control of the IgH super enhancer elements18. A pooled analysis showed that a PFS benefit was observed in patients with t (4;14) and amp1q21 with ixazomib-based therapy19. Coincidentally, in our cohort, patient #7 with amp1q21 and t (4; 14), CR was obtained after conversion from RCd to ICd regime. The other two patients (#8 and #9) had both 17p- and IgH-NSD2 cytogenetic abnormalities that converted to ICd and DRd, respectively, but only achieved PR. There were three breakpoint observed in IgH::NSD2 (no-disruption, early-disruption and late-disruption)16,20. Stong et al.16indicated ~ 25% of t (4;14) patients had an overall survival (OS) < 24 months. Biomarkers associated with this poor outcome included translocation breakpoints located within the NSD2 gene (later disruption) or accompanied by additional abnormal cytogenetics, such as deletion 17p or 1p. (d) Patient with t (11;14) was insensitive to both lenalidomide and ixazomib (patient #12). As reported in the literature21,22,23, patients with t (11;14) had some unique characteristics, such as poorer response to single novel agent-based induction therapy, even with the use of RVD regimens, it had inferior outcomes compared to the other standard risk myeloma. Since bcl-2 is highly expressed among MM patients carrying the t (11;14), there were growing number of reports indicating venetoclax for treatment myeloma patients with t (11;14)24,25. (e) Second-line treatment with daratumumab based treatment was more likely to achieve CR (patient #3 and #13). A pooled meta-analysis including MAIA, ALCYONE, and CASSIOPEA for TI-NDMM26,27,28demonstrated that the addition of Daratumumab to each control group at induction, significantly improved PFS and MRD-negativity rates. But the higher incidence of neutropenia and infections need to take into account, especially in the frail patients26,29,30.

A limitation of the current study is that our study sample size was not completed as planned due to the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s approval of Daratumumab as a first-line health insurance indication for the TI-NDMM in the year 2023. Another limitation is that our second-generation sequencing was performed in only a small subset of patients, resulting in a lack of complete biological data for all patients to explore primary drug resistance, so the conclusions may be biased, and more complete data will be needed in the future to confirm the current conclusions. However, as a standard RCT study, we had no patient loss of follow-up, and the limited data provided some reliable results. Trends in ORR benefit with ICd had seemed, especially in patients with high-risk cytogenetics. Many studies31,32,33 have suggested that Ixazomib prolongs PFS in high-risk RRMM. With fewer dose reduction and discontinuation during treatment, ICd and RCd regimens were well tolerated and feasible for TI-NDMM. Intravenous injection of CTX 750 mg/m2 on the first day of each cycle was safe and well tolerated.

In conclusion, this study at least provides good clinical guidance for doctors who choose the ICd or RCd regimen as first-line treatment in TI-NDMM. With nearly two-year of PFS times and about 85% estimated 3-year OS times, it provides ample opportunity for patients to expect and convert to new subsequently launched drugs.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Durie, B. G. M. et al. Bortezomib with Lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus Lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open- label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389, 519–527 (2017).

O’Donnell, E. K. et al. A phase 2 study of modified Lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 182, 222–230 (2018).

Medhekar, R., Ran, T., Fu, A. Z., Patel, S. & Kaila, S. Real-world patient characteristics and treatment outcomes among nontransplanted multiple myeloma patients who received bortezomib in combination with Lenalidomide and dexamethasone as first line of therapy in the united States. BMC Cancer. 22 (1), 901–909 (2022).

Palumbo, A. et al. Continuous therapy versus fixed duration of therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 33 (30), 3459–3466 (2015).

Benboubker, L. et al. Lenalidomide and Dexa methasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl. J. Med. 371, 906–917 (2014).

Facon, T. et al. Oral Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 137 (26), 3616–3628 (2021).

Durie, B. G. M. et al. Bortezomib with Lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus Lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389 (10068), 519–527 (2017).

Kumar, S. K. et al. Lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (CRd) for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results from a phase 2 trial. Am. J. Hematol. 86, 640–645 (2011).

Pawlyn, C. et al. Lenalidomide combined with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone is effective and well tolerated induction treatment for newly diagnosed myeloma patients of all ages. Blood 122, 540–540 (2013).

Kumar, S. K. et al. Phase 1/2 trial of Ixazomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in patients with previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 8 (8), 70–79 (2018).

Dimopoulos, M. A. et al. All-oral Ixazomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Eur. J. Cancer. 106, 89–98 (2019).

Rajkumar, S. V. et al. International myeloma working group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 15 (12), e538–e548 (2014).

Kumar, S. et al. International myeloma working group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 17 (8), e328–e346 (2016).

Facon, T. et al. MAIA trial investigators. Daratumumab plus Lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl. J. Med. 380 (22), 2104–2115 (2019).

Li, J. R. et al. Enhancing prognostic power in multiple myeloma using a plasma cell signature derived from single-cell RNA sequencing. Blood Cancer J. 14 (1), 38–46 (2024).

Stong, N. et al. The ___location of the t (4;14) translocation breakpoint within the NSD2 gene identifies a subset of patients with high-risk NDMM. Blood 141 (13), 1574–1583 (2023).

Qiang, Y. W. et al. MAF protein mediates innate resistance to proteasome Inhibition therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood 128 (25), 2919–2930 (2016).

Keats, J. J., Reiman, T., Belch, A. R. & Pilarski, L. M. Ten years and counting: so what do we know about t (4;14) (p16;q32) multiple myeloma. Leuk lymphoma. ;47(11):2289–2300. (2006).

Chng, W. J. et al. A pooled analysis of outcomes according to cytogenetic abnormalities in patients receiving ixazomib- vs placebo-based therapy for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 13 (1), 14–23 (2023).

Bors, A. et al. IGH::NSD2 fusion gene transcript as measurable residual disease marker in multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel). 16 (2), 283–294 (2024).

Lakshman, A. et al. Natural history of t (11;14) multiple myeloma. Leukemia 32, 131–138 (2018).

Leiba, M. et al. Translocation t (11;14) in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma: is it always favorable? Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 55, 710–718 (2016).

Jonathan, L. et al. Outcomes of myeloma patients with t (11;14) receiving Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) induction therapy. Blood 132 (Supplement 1), 3282 (2018).

Kumar, S. et al. Efficacy of venetoclax as targeted therapy for relapsed/refractory t (11;14) multiple myeloma. Blood 130, 2401–2409 (2017).

Kumar, S. K. et al. Venetoclax or placebo in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (BELLINI): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1630–1642 (2020).

Kumar, S. K. et al. Updated analysis of daratumumab plus Lenalidomide and dexamethasone (D-Rd) versus Lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in patients with transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM): the phase 3 MAIA study. Blood 136, 24–26 (2020).

Moreau, P. et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 394 (10192), 29–38 (2019).

Giri, S. et al. Evaluation of daratumumab for the treatment of multiple myeloma in patients with high-risk cytogenetic factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 6 (11), 1759–1765 (2020).

Stege, C. A. M. et al. Ixazomib, daratumumab, and Low-Dose dexamethasone in frail patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the hovon 143 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (25), 2758–2767 (2021).

Groen, K. et al. Ixazomib, daratumumab and low-dose dexamethasone in intermediate-fit patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label phase 2 trial. E Clin. Med. 63, 10216–10227 (2023).

Richardson, P. G. et al. Ixazomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin. Phgroupacother. 19 (17), 1949–1968 (2018).

Liu, A. et al. Assessment of prolonged proteasome Inhibition through ixazomib-based oral regimen on newly diagnosed and first-relapsed multiple myeloma: A real-world Chinese cohort study. Cancer Med. 13 (9), e7177–7186 (2024).

Avet-Loiseau, H. et al. Ixazomib significantly prolongs progression-free survival in high-risk relapsed/refractory myeloma patients. Blood 130 (24), 2610–2618 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the laboratory in the department of hematology for their cooperation during the research.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070227 ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and JQ.M. designed the study. Y.W and YF.L. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. Y.T., SW.J., YF.L., WP.Z. and JL.C. participated in the patient data collection. Y.W., SF.J and JQ.M. provided the consultancy, corrections, and comments. JQ.M. and SF.J. supervised the research. JQ.M. provided the foundations. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and correction and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Internal Review Board (IRB) of Ruijin Hospital approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yan Wang and Yuan-Fang Liu contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Liu, YF., Jin, SW. et al. Ixazomib or Lenalidomide combined with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in the treatment of elderly transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Sci Rep 15, 6538 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91126-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91126-5