Abstract

Heterogeneous single-atom catalysts (SACs) have gained significant attention for their maximized atom utilization and well-defined active sites, but they often struggle with multi-stage organic cross-coupling reactions due to limited coordination space and reactivity. Here, we report an “anchoring-borrowing” strategy combined facet engineering to develop artful single-atom catalysts (ASACs) through anchoring foreign single atoms onto specific facets of the non-innocent reducible carriers. ASACs exhibit adaptive coordination, effectively bypassing the oxidative-addition prerequisite for bivalent elevation at a single metal site in both homogenous and heterogeneous cross-couplings. For example, Pd1-CeO2(110) ASAC exhibits unparalleled activity in coupling with more accessible aryl chlorides, and challenging heterocycles, outperforming traditional catalysts with a remarkable turnover number of 45,327,037. Mechanistic studies reveal that ASACs leverage dynamic structural changes, with reducible carriers acting as electron reservoirs, significantly lowering reaction barriers. Furthermore, ASACs enable efficient synthesis of biologically significant compounds, drug intermediates, and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) through a scalable high-speed circulated flow synthesis, underscoring great potential for sustainable fine chemical manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction is a cornerstone for organic synthesis, playing a crucial role in the fine chemical and pharmaceutical industries1,2,3,4,5,6. Despite the impressive performance of traditional homogeneous catalysts, they face challenges such as high costs, difficulties in catalyst recycling, and metal contamination in products7. In addition, the transition of the central metal atom from 0 valence to +2 valence during oxidative addition presents a significant energy barrier. In subsequent transmetallation and reductive elimination processes, a continuous evolution of valence states is imperative, placing high demand on the valance state change of the transition metal center. The search for highly efficient and selective heterogeneous catalysts for cross-coupling reactions is essential for advancing both fundamental chemistry and sustainable industrial production of fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals8,9.

Heterogeneous single-atom catalysts (SACs)10,11,12,13,14 have emerged as a promising class of catalytic materials, attracting considerable interest for their ability to maximize atom utilization and provide well-defined active sites15,16,17, effectively linking the advantages of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis in organic synthesis18,19,20. In general, the design of the support must ensure the stability of the metal center while allowing structural flexibility to achieve a highly active catalytic cycle. However, the chemical bonds between the metal centers and the support, which are necessary to prevent metal aggregation, often result in spatial constraints that limit the activation and adsorption of both coupling substrates. This restricts mononuclear metal species from effectively facilitating multi-stage organic cross-coupling reactions21,22,23.

Here, we demonstrate a novel “anchoring-borrowing” strategy combined with facet engineering of non-innocent reducible supports to create a class of artful single-atom catalysts (ASACs). This approach involves anchoring foreign single atoms onto specifically chosen facets of reducible metal oxides, allowing for the simultaneous “borrowing” of coordination oxygen as anchor sites and the carrier as an electron reservoir to form ASACs (Fig. 1a). These ASACs exhibit adaptive structures and distinct valence state evolution, effectively bypassing the need for bivalent changes at a single metal site, which is typically required in both conventional homogeneous and heterogeneous cross-couplings. For instance, Pd1-CeO2(110) ASAC demonstrates exceptional activity, even with less reactive aryl chlorides and challenging heterocyclic substrates. It outperforms traditional catalysts with high yields and remarkable stability, achieving a record-breaking turnover number (TON). Beyond the mechanistic insights, scalable high-speed circulated flow synthesis underscores the promising potential of ASACs for practical and large-scale synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates and products.

a Rational design of ASAC for cross-coupling reactions, where M1 denotes the foreign single-metal-atom introduced to the reducible carriers. b Using single-atom Pd1 anchored on the reducible CeO2 as a representative example, this panel illustrates the dynamic structural and valence state evolution of the Pd1 ASAC, which effectively circumvent the energy barrier for oxidative addition in cross-coupling reactions, in contrast to traditional homogeneous catalyst systems where the reaction rate is largely limited by this step. The white, gray, green, orange, red, yellow, and blue spheres represent hydrogen, carbon, boron, bromine, oxygen, cerium, and palladium atoms, respectively. The pink and blue regions represent charge accumulation and loss, respectively.

Results

The design of ASACs

ASACs can be created through the immobilization foreign single atoms on specific reducible metal oxide supports via their intrinsic surface oxygen coordination sites. For instance, the design of Pd1 ASACs is achieved by anchoring Pd single atoms (Pd1) on reducible CeO2 support, particularly effective on the (110) facet. On this facet, Ce and Pd atoms are simultaneously exposed at the outermost surface. The reducible CeO2 support not only donates electrons to the metal center but also features surface-exposed Ce sites that preferentially adsorb halide ions during the oxidative addition process, facilitating the dissociation of aryl halides while providing adsorption sites for the dissociated halide ions. In contrast, anchoring Pd1 on the CeO2 (111) facet is predicted to be energetically unfavorable (Supplementary Table 1)24. Furthermore, Ce atoms on the CeO2 (100) surface are embedded and fully coordinated by oxygen atoms, preventing these Ce sites from assisting dopant atoms in activating aryl halides. (Supplementary Fig. 1). On the CeO2 (110) surface, both Pd and Ce sites are exposed and positioned close to each other, linked by two bridging oxygen atoms on the outermost surface. This structural proximity, combined with the sufficient electron-modulation ability of the reducible CeO2 support, enable Pd1 ASAC operates through dynamic structural changes, primarily involving the Pd centers, while the electron supply for Pd-catalyzed oxidative addition is predominantly provided by the reducible CeO2 support. It allows ASAC to effectively adsorb and activate both reactant substrates for cross-coupling reactions (Fig. 1a). This contrasts with homogeneous Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling, which occurs over a single metal site and typically requires the elevation of valence state from Pd (0) to Pd ( + 2), resulting in high energy barriers. Here, the valence state of Pd site in ASAC during the oxidative addition remains nearly unchanged, attributed to the dynamic structural and charge state evolution. The energy cost of dynamic Pd-O bonding evolution is mitigated by subsequent interactions of the Pd atoms with the phenyl group and halogen species during oxidative addition, leading to a significantly reduced reaction barrier (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2).

The synthesis and characterization of ASACs

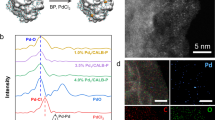

Pd1 ASACs were prepared by first calcining Ce(CH3COO)3·xH2O to create CeO2 support with abundance of (110) facets, as verified by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (ADF-STEM, Supplementary Fig. 3b) characterization techniques. Pd single atoms were then anchored onto these CeO2 supports using the established two-step annealing protocols (refer to experimental methods)25. The intrinsic O atoms on the CeO2 surface can serve as coordination sites for Pd, forming ASAC. We also synthesized a series of catalysts with single-atom Pd loaded on various supports for comparison. A range of characterization tools were employed to elucidate local coordination structures of Pd1 ASACs and other reference samples. ADF-STEM confirmed the presence of isolated Pd single atoms in the Pd1-NC (Fig. 2b), Pd-Al2O3 (Fig. 2c) and Pd1 ASACs (Fig. 2d), with no observation of Pd nanoparticles or clusters. Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) mapping further revealed that the Pd atom are coordinated by O atoms situated between two Ce atoms, forming an atomically dispersed Pd1 ASAC site24,26. Furthermore, Fourier-transformed Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra of Pd K-edge acquired over Pd1 ASACs and other SACs (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 2) all exhibit prominent features centered at 1.5 Å, attributed to the first Pd-O/N coordination shell. Notably, Pd1 ASAC possess a distinct peak around 2.9 Å, which is assigned to the second Pd-O-Ce shell27,28,29. No features associated with Pd-Pd metallic bonding were observed, confirming the atomic dispersion of Pd in all the ASAC and SAC samples. This observation is consistent with the absence of diffraction peaks associated with metallic Pd species in the powder XRD spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

a Illustrate atomic structures of single Pd atom on NC (left), Al2O3 (right) and CeO2 (middle). Atomic-resolution ADF-STEM image of Pd1-NC (b) and Pd1-Al2O3 (c). d Atomic-resolution ADF-STEM images and EELS mapping of Pd1 ASAC supported by CeO2. Insert is the intensity profile along the dashed yellow line. e Pd K-edge Fourier transformed EXAFS spectra, with dotted lines representing the fitted data.

Further analysis of the Pd K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3d) reveal that Pd1 ASAC displays a higher white line intensity and rising edge energy compared to Pd foil, with a shape and intensity distribution similar to that of PdO. This suggests an oxidation state of approximately +2 for Pd single atoms on CeO2 support. A comparison between the experimental and the calculated XANES spectra of various proposed structures (Supplementary Figs. 4a–d) reveals that Pd1 ASAC containing PdO4 motif on the CeO2 (110) facet closely matches the experimental plot. The valence states of both Pd and Ce in the catalyst are further evaluated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Specifically, the peak at 338.0 eV in the Pd 3 d5/2 spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 3e) can be assigned to the Pd2+ species, consistent with the XANES results30,31,32. In addition, in the Ce 3d spectrum, peaks at 884.8 eV and 902.9 eV indicate the presence of Ce3+ species, while the remaining peaks correspond to Ce4+ species14,33. Notably, the peak area ratio of Ce3+ to Ce4+ increases after the introduction of Pd atoms, suggesting a higher proportion of Ce3+ species upon Pd loading. Additionally, the Ce 3 d spectrum of Pd1 ASAC exhibits a shift of 0.4 eV compared to CeO2, presumably due to the higher electronegativity of doped Pd compared to Ce (Supplementary Fig. 3f)34.

Performance in cross-coupling reactions

We first evaluated the catalytic performance of Pd1 ASAC in Suzuki coupling reactions using various aryl halides and aryl boronic acids (ArB(OH)2). Pd1 ASAC demonstrated exceptional performance as a heterogeneous catalyst, exhibiting excellent activity and a broad substrate scope in cross-coupling reactions with aryl iodides, bromides, and chlorides, across a range of electronic and steric characteristics (Fig. 3). Conventional heterogeneous Pd SACs typically exhibit low activity towards aryl chloride substrates due to the stronger carbon-chlorine bond and increased difficulty of the oxidative addition step compared to aryl bromides and iodides. However, Pd1 ASAC effectively overcomes this challenge with a highly adaptive active center, significantly enhancing the Suzuki coupling reaction with aryl chloride substrates (4a to 4 f). Substrates with electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups were converted into target products in high yield and selectivity, outperforming conventional homogeneous catalysts and reported heterogeneous catalysts (Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, Pd1 ASAC demonstrates superior performance with heterocyclic substrates that are difficult to promote in homogeneous catalysis, achieving reaction products (4 g to 4o) with good isolated yields. Beyond aryl boronic acids, Pd1 ASAC demonstrates high efficiency with a range of boron reagents, including aryl potassium trifluoroborates (ArBF3K), alkenyl-pinacolatoboryl (Bpin), and catecholatoboryl (Bcat). Moreover, Pd1 ASAC exhibits remarkable versatility in facilitating Heck reactions with aryl halides and alkenes, as well as Sonogashira reactions involving aryl halides and alkynes (Supplementary Fig. 5), highlighting its broad applicability across diverse C−C coupling reactions.

The conditions of different substrates are shown in Supplementary Fig. 22.

Furthermore, Pd1 ASAC demonstrates superior stability and recyclability in Suzuki couplings. Under both high-conversion (~99%, Supplementary Fig. 6a) and low-conversion conditions (~60%, Supplementary Fig. 7), the catalyst maintains high activity with minimal loss even after 10 cycles. These results indicate its durability in practical applications. The catalyst’s heterogeneity was further confirmed through thermal filtration experiments and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analysis (refer to Supplementary Table 4 for details). The results revealed that the Pd content in the catalyst remained virtually unchanged before and after the reaction, with no detectable Pd residue in the solution. Additionally, XRD, XPS, and EXAFS analyzes also confirmed that the atomic structure of Pd in the recovered catalyst was consistent with that of the fresh Pd1 ASAC (Supplementary Figs. 6b, c, and d). Owing to its remarkable activity and stability, Pd1 ASAC achieved a TON up to 45,327,037 in cross coupling reactions, defined as the mole of converted aryl halides/mole of Pd catalyst (refer to Supplementary Fig. 8 for detailed reaction conditions and analysis). This TON is several orders of magnitude higher than those reported for previously known catalysts35,36,37.

Mechanistic elucidation with supporting evidence

We first conducted Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to gain theoretical insights into the superior catalytic performance of Pd1 ASAC in Suzuki couplings (Fig. 4). Typically, three crucial steps including oxidative addition, transmetallation, and reductive elimination are involved in Suzuki coupling (Supplementary Fig. 9). In the oxidative addition, the reaction initiates with bromobenzene approaching the Pd site, leading to a dynamic evolution of the catalytic center of ASAC. This involves the opening of two Pd-O bonds in the PdO4 motif accompanied with partial reduction of the Pd atom. Subsequently, bromobenzene dissociates with an energy barrier of 0.72 eV (TS1), which is predicted to be a rate-determining step and aligns with experimental reaction kinetics studies (Supplementary Figs. 10–12). The Pd atom subsequently coordinates with the dissociated phenyl and bromine species, forming a new planar four-coordinate configuration II, while the bromine species also interacts with an adjacent Ce site. The corresponding chemical reaction equations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. During this process, the Bader charge of the Pd atom shows minimal change, whereas the electron demanded for the oxidative addition is met by the reducible CeO2 support in its Bader charge from −0.35 |e| to +0.24 |e | . Under alkaline conditions, the bromine species is readily substituted by a hydroxide group. The alkaline-activated phenylboronic acid dissociates into boronic acid and phenyl groups, with phenyl groups adsorbing onto the Pd atom, while the hydroxide group interacts with both Pd and adjacent Ce atoms. The two phenyl groups then couple to form the biphenyl product. During this reductive elimination step, the Bader charge of CeO2 support gradually decreases from +0.1 |e| to −0.21 |e| and then to −0.64 |e | . Meanwhile, the Bader charge of the Pd atom shows only a minimal increase from +0.41 |e| (TS2) to +0.64 |e| (original state of ASAC).

To understand the driving force behind these adaptive coordination behaviors, we analyzed the evolution of the electronic structure of Pd1 ASAC during the reaction (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 14). The density of states (DOS) and crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) calculation reveal that Pd-O bonds of the original PdO4 motif exhibit significant antibonding character near the Fermi level (EF). In contrast, the antibonding characters in the tetra-coordinated structure formed after the dissociation of bromobenzene are notably reduced. The integrated COHP (ICOHP) further confirms that the Pd center exhibits stronger bonding interactions after bromobenzene dissociation ( − 5.24 eV vs. − 3.47 eV). Thus, the energy cost of opening two Pd-O bonds is offset by the subsequent interactions of the Pd atoms with the phenyl group and Br species during oxidative addition. Additionally, in the square planar PdO4 motif (Pd1 ASAC), the d band center of Pd is positioned significantly below the EF. When two Pd-O bonds in PdO4 motif are opened to form new tetra-coordinated structures (step II), the d-orbital centers of Pd shift closer to EF, indicating the active role of Pd atoms during the reaction. As a result, the Pd1 ASAC can adaptively regulate the Pd electronic structure to facilitate catalysis through dynamic changes in coordination configuration. The PDOS analysis for the 5d-orbitals of Ce revealed a slight decrease in the integrated occupied state below EF and a gradual increase in empty states, with these empty states shifting toward EF. All these observations indicate the accumulation of positive charge over Ce as the reaction proceeds (from initial state Pd1 ASAC to step IV). These results stem from the partial electron depletion from the CeO2 support, which prevents continuous charge oxidation of a single Pd site (e.g., from +2 to +4), thereby significantly lowering the reaction barrier.

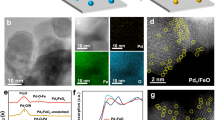

To validate the calculated reaction mechanisms, we preformed operando XANES of Pd K edge to monitor the local structure evolution of Pd atom during the reaction. The results show that the oxidation state of Pd in Pd1 ASAC remains essentially unchanged during the Suzuki coupling reaction, consistent with our calculated Bader charge evolution (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 15). To further demonstrate the critical role of crystal facets as predicted, we also employed the facet-controlled synthesis to prepare three different CeO2 samples with predominantly (111), (110), and (100) facets exposed, onto which Pd single atoms were loaded, as revealed in the corresponding HRTEM images (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 16). While the coordination environment of Pd atomic differs in these samples, it all remains atomically dispersed irrespective of the crystal facet onto which they were loaded (Supplementary Figs. 17–18). The Pd1 loaded on the CeO2(110) sample exhibits exceptional performance in coupling reactions with aryl halides and phenylboronic acid. In contrast, Pd single atoms on the other two crystal facets showed negligible activity (see Fig. 5e), corroborating our theoretical finding and analysis above.

a Operando Pd K-edge XANES of Pd1 ASAC catalyst measured under the Suzuki coupling reaction conditions. b Corresponding Bader charge of Suzuki cross-coupling reaction over the Pd1 ASAC. c Yield of biphenyl after two-hour reaction for Pd single atoms loaded on different supports at 298 K. d DFT Model and high-resolution TEM images of Pd1-CeO2(111), Pd1-CeO2(110) ASAC, Pd1-CeO2(100). e Activity of Suzuki cross-coupling catalyzed by Pd single atoms supported on facet-dependent CeO2. Conditions: 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (ArB(OH)2, 0.6 mmol), Pd1-CeO2(110) ASAC (5 mg, 0.35 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), H2O/EtOH (2 mL:2 mL), 25 °C, 2 h.

To further verify the universality of the unique electron-donating ability of reducible supports, we synthesized a series of catalysts with single-atom Pd loaded on various supports for performance evaluation (Supplementary Figs. 19–20). Using the coupling between bromobenzene and phenylboronic acid as a model reaction, we assessed these catalysts, each containing the same amount of Pd (0.02 mol%), under consistent reaction conditions: 298 K for 2 h (Fig. 5c), 323 K for 2 h (Supplementary Fig. 21a), and 353 K for 1 h (Supplementary Fig. 21b). Pd1 supported on reducible metal oxides demonstrated notable performance including CeO2, Co3O4, TiO2, and Fe2O3. Among them, Pd1 on CeO2(110) still gave the highest activity under all tested conditions. In contrast, non-reducible supports such as N-doped carbon38 (Pd1-NC) or Al2O3 (Pd1-Al2O3) exhibit no activity, even at 353 K. In the case of Pd1-NC, the local coordination of Pd atoms is saturated, while on Pd1-Al2O3, the Al atoms from the support is not able to donate charge efficiently during the reactions. Consequently, neither of these supports can effectively trigger the reactions (Supplementary Videos 1–3). This comparative experiment highlights the importance of reducible supports in creating highly adaptive ASAC sites, thereby promoting efficient cross-coupling reactions.

Synthetic applications and scalable flow synthesis

After gaining mechanistic insights, we further explored the application of Pd1 ASAC in synthesizing biologically significant compounds and therapeutic agents (Fig. 6a). Notably, Pd1 ASAC has demonstrated high efficacy in producing important drug intermediates with moderate to excellent yields. Aryl bromides, including those with substantial steric hindrance and strongly coordinating substituents such as nitro groups, reacted smoothly with aryl boronic acids, leading to the successful formation of products (4ae, 4af, 4ah, 4aj) with satisfactory yields. Additionally, the catalyst exhibits excellent tolerance for unprotected functional groups, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, producing the desired products (4ag, 4ai) in high yields.

a The synthesis of key intermediates of drug molecules. b Modification of drug molecules. c The synthesis of pesticide. d Large-scale circulated flow synthesis of bifenazate. Conditions: a: 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (ArB(OH)2, 1.5 mmol), Pd1 ASAC (5 mg, 0.35 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), THF/H2O (2 mL: 2 mL), 100 °C, 36 h. b: 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (ArB(OH)2, 0.6 mmol), Pd1 ASAC (5 mg, 0.35 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), EtOH/H2O (2 mL: 2 mL), 80 °C, 10 h. c: 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (ArB(OH)2, 0.6 mmol), Pd1 ASAC (5 mg, 0.35 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), EtOH/H2O (2 mL: 2 mL), 100 °C, 20 h. d: 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (ArB(OH)2, 0.6 mmol), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), Pd1 ASAC (5 mg, 0.35 mol%), THF/H2O (2 mL: 2 mL), 100 °C, 24 h, isolated yield. e: 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (ArB(OH)2, 2.5 mmol), Pd1 ASAC (10 mg, 0.7 mol%), K2CO3 (2.5 mmol), THF/H2O (2 mL: 2 mL), 100 °C, 36 h. The synthesis conditions of bifenazate are shown in Supplementary Figs. 24 and 27.

The preferential reactivity of aryl iodides over aryl bromides, leading to the formation of product 4ak in a good yield, highlighting the potential for diverse transformations of aryl halides. Additionally, the Pd1 ASAC’s remarkable reactivity and stability underscore its application for late-stage modifications of complex biologically relevant scaffolds and drug molecules. This method effectively facilitates the generation of late-stage-derivatized products (4am-4ao) in good yields from a pharmaceutical compound benzbromarone (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, Pd1 ASAC was effective in the multistep synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds. For example, the synthesis of bifenazate, a novel acaricide used to control spider mites across various crops, was achieved using 5-bromo-2-methoxyaniline as the starting material. The cross-coupling precursor 1aa was successfully prepared and subsequently subjected to Pd1 ASAC catalyzed cross-coupling with phenylboronic acid. This process yielded bifenazate in a 92% isolated yield (Fig. 6c).

The automated synthesis of organic molecules using a flow reactor presents significant industrial advantages39, including enhanced efficiency, scalability, and safety. We further employed Pd1 ASAC in a high-speed circulation flow reactor40 (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Figs. 25–27), designed for heterogeneous catalysis in a flow motion. A customized circulation flow system was assembled, comprising a reagent reservoir, a peristaltic pump, a perfluoroalkoxyalkane (PFA) tubing coil, and a heating module. At a 10-gram scale, the substrate 1 u was mixed with 400 mg Pd1 ASAC, 12 g phenylboronic acid and 13.8 g potassium carbonate in 240 mL of EtOH/H2O (2:1) to form a slurry. The slurry was continuously pumped at 40 mL/min through the PFA tubing reactor (outer diameter (O.D.) = 4.8 mm, inner diameter (I.D.) = 3.2 mm, volume (V) = 240 mL), which was heated to 80 °C with the heating module (All setup parameters were optimized according to Supplementary Fig. 18). The reaction mixture was recirculated back to the reservoir until the reaction was completed, yielding bifenazate in 86% isolated yield. The high-speed circulation flow exhibited significantly improved reaction rates compared to conventional batch synthesis (5 h vs. 12 h) due to superior mixing efficiency. These results underscore the catalyst’s efficacy in modifying and synthesizing complex pharmaceuticals, with the high-speed circulation flow synthesis demonstrating its potential for practical applications in the pharmaceutical industry.

Discussions

Our work demonstrates that ASACs fabricated through the “anchoring-borrowing” strategy combined with non-innocent reducible support facet engineering exhibit outstanding activity and stability even in coupling with less reactive aryl chlorides or challenging heterocyclic substrates, surpassing conventional catalysts with high yields and exceptional stability, achieving a record-breaking TON. Such ASAC operates through dynamic structure changes and effectively circumvents the need for bivalent changes at a single metal site in both conventional homogeneous and heterogeneous Suzuki couplings, significantly lowering the reaction barrier. Furthermore, ASACs exhibit extraordinary efficiency in synthesizing biologically significant compounds, drug intermediates, and pharmaceutical compounds through a scalable high-speed circulated flow synthesis, underscoring their remarkable potential for sustainable fine chemical manufacturing.

Methods

Synthesis of CeO2

Ce(CH3COO)3·xH2O was heated in a muffle furnace at 350 °C (with a heating rate of 2 °C min−1) for 2 h. Subsequently, the temperature was improved to 550 °C (at a heating rate of 2 °C min−1) for 5 h to obtain CeO2.

Synthesis of CeO2(100)

9.6 g sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was dissolved in 35 mL deionized water. 0.868 g Ce(NO3)3·6H2O was dissolved in 5 ml of deionized water. Subsequently, the cerous nitrate solution is slowly added in drops to the sodium hydroxide solution, which is constantly stirred. The obtained slurry was placed in a Teflon bottle, which was stirred for 30 mins. The Teflon bottle was placed inside a tightly sealed stainless-steel vessel autoclave, which was then placed into a temperature-controlled electric oven and subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 180 °C for 24 h. After completion, products were separated via centrifugation, followed by washing with H2O/EtOH. Subsequently the precipitates were dried overnight at 60 °C in air. The resulting products were annealed in air at 500 °C for 2 h, yielding light-yellow powders.

Synthesis of CeO2(110)

The other procedures were the same as those described above, except that the hydrothermal treatment was changed to 140 °C for 18 h.

Synthesis of CeO2(111)

325.73 mg Ce(NO3)3·6H2O and 1.24 mg sodium phosphate (Na3PO4) were mixed in 30 mL of deionized water. The other procedures were the same as those described above, except that the hydrothermal treatment was changed to 170 °C for 12 h.

Synthesis of Pd1-facet-dependent CeO2

PdCl2 (2 mg) and CeO2 (300 mg) were dispersed in 0.5 M HCl solution (30 mL), mixed well with vigorous stirring, sonicated for 30 min, and then evaporated to dryness by a rotary evaporator. Subsequently, it was dried at 70 °C, and then annealed at 300 °C (with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1) for 5 h. After a thorough wash with DMSO, two more washes with EtOH/H2O and drying at 80 °C, the powder was heated at 500 °C for 5 h under static air (at a heating rate of 1 °C min−1).

Synthesis of Pd1-different metal oxide supports

Metal oxides were obtained by calcining their nitrate precursors in the same manner as preparing CeO2. The metal salt precursor was replaced with (NH4)2PdCl4 (1.8 mg) and dispersed it and the metal oxide (300 mg) in deionized water (30 mL). The subsequent process was the same as the preparation of Pd1-CeO2.

Synthesis of Pd1-PCN

Dicyandiamide was calcined at 550 °C (heating rate, 2.3 °C min−1) for 4 h in a muffle furnace, after which it was thermally exfoliated at 500 °C (heating rate, 5 °C min−1) for 5 h to obtain the PCN nanosheets. The fabrication of Pd1-PCN is consistent with that of Pd1-CeO2, except that the first and second heating steps need to be carried out under nitrogen protection, and the drying step is carried out in a vacuum oven.

Synthesis of Pd1-NC

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (7.65 g) and 2-methylimidazole (17.49 g) were dispersed in 600 mL deionized water, respectively. The two were quickly mixed and stirred and then left to stand for 12 h. The two-dimensional zeolite imidazolate framework (2D-ZIF-8) was separated by centrifugation, washed with EtOH/H2O, and then dried overnight at 80 °C. A mixture of 1 g of 2D-ZIF-8 and 20 g of KCl was mixed in 80 mL of deionized water and subjected to rotary evaporation for drying. The dried product was then heated to 110 °C overnight. Subsequently, the material was heated to 700 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere at a rate of 2 °C min−1 for 5 h. NC was acquired by washing with 2 M HCl, EtOH/H2O solution, and drying at 80 °C overnight. Except that the first and second heating temperatures are 200 °C and 550 °C, respectively, the preparation of Pd1-NC is consistent with that of Pd1-PCN.

Material characterization

Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were carried out on a Bruker D8 Focus Powder X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) at room temperature. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained with an FEI Titan 80-300 S operated at 200 kV. ADF-STEM imaging was carried out using an aberration-corrected JEOL ARM-200F system equipped with a cold field emission gun and an ASCOR aberration corrector, EELS mapping (200 kV by a Gatan Quantum ER system with a frame exposure time of 10 s), EDS (200 kV by an Oxford Aztec EDS system). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out in a custom-designed ultrahigh-vacuum system with a base pressure lower than 2 × 10−10 mbar. Al Kα (hν = 1486.7 eV) was used as the excitation source for XPS. The metal loadings in all the samples were measured by ICP-AES. 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance Neo 400 or 500 spectrometers. X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of Pd K-edge were measured in fluorescent mode at room temperature at beamline 7-BM QAS of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), Brookhaven National Laboratory. A Si (111) double-crystal monochromator was used to filter the X-ray beam. Metal foils were used for the energy calibration, and all samples were measured under transmission mode at room temperature. EXAFS oscillations χ(k) were extracted and analyzed using the Demeter software package41,42. Operando XAFS experiments of the Pd K-edge were performed using a Si (311) monochromator crystal at the BL14B2 beamline at SPring-8, in Japan. A custom-made cell was employed, and data were recorded in fluorescent mode at room temperature. Subsequent data processing via the ATHENA module implemented in the IFEFFIT software package43.

Suzuki cross-coupling reactions

Aryl halide, phenylboronic acid, base, catalyst, and solvent were added to the screw-top reaction tube in appropriate proportions. The reaction tube was put into an oil bath preheated to an appropriate temperature, and the stirring time was set according to the needs of different substrates. After the reaction, the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (DCM), and then the solution was evaporated utilizing a rotary evaporator. Finally, the pure product was acquired by purifying the residue by silica gel column chromatography.

Heck cross-coupling reactions

Aryl halide (0.5 mmol), terminal alkene (1 mmol), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), catalyst, 4 mL of EtOH/H2O (1:1) were added to the screw-top reaction tube. The tube was heated and stirred in a 110 °C oil bath for 10 h. The post-processing process is consistent with the Suzuki reaction.

Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions

Aryl halide (0.5 mmol), terminal alkyne (0.75 mmol), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), catalyst, 4 mL of EtOH/H2O (7:1) were added to the screw-top reaction tube. The tube was heated and stirred in a 100 °C oil bath for 10 h. The post-processing process is consistent with the Suzuki reaction.

Recyclability test

4-Bromotoluene (5 mmol), phenylboronic acid (6 mmol), K2CO3 (15 mmol), catalyst, EtOH/H2O (20 mL/20 mL) were sequentially added to the round-bottomed flask. The flask was heated and stirred in a 100 °C oil bath for 1 h. The products were extracted with DCM, and the yield was calculated by GC analysis. The catalyst was isolated by centrifugation, washed with EtOH/H2O, and dried at 80 °C overnight for the next cycle. To avoid the decrease in efficiency caused by the loss of catalyst during operation, it is necessary to keep the dosage ratio of catalyst, substrate, solvent, and base constant in each cycle.

Computational details

All DFT calculations were carried out by the Quickstep code in the CP2K package44. The exchange and correlation interactions of valence electrons are approximated by the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional45. The Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) type pseudopotential was adopted to treat the effect of core electrons, and the Gaussian and auxiliary plane wave (GPW) double zeta basis set was applied to describe the valence electron. The cut-off of 400 Rydberg was used to define the planewave cut-off for the finest level of the multi-grid, and the cut-off for the grid to map Gaussians in real space (relative cut-off energy) was set to 60 Rydberg. The single gamma-point grid sampling was adopted for Brillouin zone integration. The total energy was converged to 1 × 10−6 Rydberg during all self-consistent field (SCF) steps. The DFT + U method with the effective Hubbard term (Ueff = U - J) of 5.0 eV was used to describe Ce 4 f states, which is consistent with our previous studies46, and the Grimme’s D3 corrections method was employed to consider the dispersion interaction47. The transition states were searched by the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method, including at least 6 replicas48. All electronic structure analyzes were calculated by sampling in a 2 × 2× 1 Monkhorst-Pack grid using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) software package49,50. The Bader charge analysis is performed based on the code developed by Henkelman et al.51,52 and the projected crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) was calculated using the LOBSTER tool53,54. Detailed input files for structural optimization can be found in the supplementary information.

The CeO2(110)-p(3 × 3) surface slab was used to model the substrate with cell parameters of a = 16.23 Å, b = 11.48 Å and c = 27.65 Å. The slab consists of five atomic layers, in which the bottom two atomic layers were frozen while the remaining layers were allowed to relax. Moreover, a vacuum thickness of 20 Å was set along the z-direction to avoid interactions between periodic images. The Pd single-atom is anchored on the CeO2(110) surface hollow site, and the optimized Pd1 ASAC structure shows that Pd-O bond lengths are 2.09 Å and Pd-Ce bond lengths are 2.94 ~ 3.08 Å, which are in good agreement with the experimental results (Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Table 2). The Gibbs free energies were calculated by using the equation: G = EDFT + EZPE + H − TS, where EDFT is the DFT-calculated electronic energy, EZPE is the zero-point energy (ZPE), and H and S are the enthalpy and entropy contributions from nonimaginary vibrations.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Cui, X., Li, W., Ryabchuk, P., Junge, K. & Beller, M. Bridging homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis by heterogeneous single-metal-site catalysts. Nat. Catal. 1, 385–397 (2018).

Li, W.-H., Yang, J., Wang, D. & Li, Y. Striding the threshold of an atom era of organic synthesis by single-atom catalysis. Chem 8, 119–140 (2022).

Yan, H., Su, C., He, J. & Chen, W. Single-atom catalysts and their applications in organic chemistry. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 8793–8814 (2018).

Giannakakis, G., Mitchell, S. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Single-atom heterogeneous catalysts for sustainable organic synthesis. Trends Chem. 4, 264–276 (2022).

Yin, L. & Liebscher, J. Carbon-carbon coupling reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous palladium catalysts. Chem. Rev. 107, 133–173 (2007).

Molnar, A. Efficient, selective, and recyclable palladium catalysts in carbon- carbon coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 111, 2251–2320 (2011).

Biffis, A., Centomo, P., Del Zotto, A. & Zecca, M. Pd metal catalysts for cross-couplings and related reactions in the 21st century: a critical review. Chem. Rev. 118, 2249–2295 (2018).

Fihri, A. et al. Nanocatalysts for Suzuki cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 5181–5203 (2011).

Vásquez-Céspedes, S., Betori, R. C., Cismesia, M. A., Kirsch, J. K. & Yang, Q. Heterogeneous catalysis for cross-coupling reactions: an underutilized powerful and sustainable tool in the fine chemical industry? Org. Process Res. Dev. 25, 740–753 (2021).

Lang, R. et al. Single-atom catalysts based on the metal-oxide interaction. Chem. Rev. 120, 11986–12043 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Rh single atoms on TiO2 dynamically respond to reaction conditions by adapting their site. Nat. Commun. 10, 4488 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. C-C coupling on single-atom-based heterogeneous catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 954–962 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. A heterogeneous single-atom palladium catalyst surpassing homogeneous systems for Suzuki coupling. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 702–707 (2018).

Tao, X. et al. Anchoring positively charged Pd single atoms in ordered porous ceria to boost catalytic activity and stability in suzuki coupling reactions. Small 16, 2001782 (2020).

Sun, T. et al. Ferromagnetic single-atom spin catalyst for boosting water splitting. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1–9 (2023).

Li, Z. J. et al. Tuning the spin density of cobalt single-atom catalysts for efficient oxygen evolution. ACS Nano 15, 7105–7113 (2021).

Sun, T. et al. Design of local atomic environments in single‐atom electrocatalysts for renewable energy conversions. Adv. Mater. 33, 2003075 (2021).

Ma, Z. et al. Development of Iron‐based single atom materials for general and efficient synthesis of amines. Angewandte Chemie, 63, e202407859, (2024).

Wang, A., Li, J. & Zhang, T. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 65–81 (2018).

Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Kaiser, S. K., Chen, Z., Fuast Akl, D., Mitchell, S. & Pérez-Ramίrez, J. Single-atom catalysts across the periodic table. Chem. Rev. 120, 11703–11809 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Well-defined materials for heterogeneous catalysis: from nanoparticles to isolated single-atom sites. Chem. Rev. 120, 623–682 (2020).

Hai, X. et al. Geminal-atom catalysis for cross-coupling. Nature 622, 754–760 (2023).

Hu, B. et al. Distinct crystal‐facet‐dependent behaviors for single‐atom palladium‐on‐ceria catalysts: enhanced stabilization and catalytic properties. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107721 (2022).

Hai, X. et al. Scalable two-step annealing method for preparing ultra-high-density single-atom catalyst libraries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 174–181 (2022).

Xin, P. et al. Revealing the active species for aerobic alcohol oxidation by using uniform supported palladium catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 57, 4732–4736 (2018).

Muravev, V. et al. Interface dynamics of Pd-CeO2 single-atom catalysts during CO oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 469–478 (2021).

Hinokuma, S., Fujii, H., Okamoto, M., Ikeue, K. & Machida, M. Metallic Pd nanoparticles formed by Pd-O-Ce interaction: a reason for sintering-induced activation for CO oxidation. Chem. Mater. 22, 6183–6190 (2010).

Jeong, H., Bae, J., Han, J. W. & Lee, H. Promoting effects of hydrothermal treatment on the activity and durability of Pd/CeO2 catalysts for CO oxidation. ACS Catal. 7, 7097–7105 (2017).

Mouat, A. R. et al. Synthesis of Supported Pd0 nanoparticles from a single-site Pd2+ surface complex by alkene reduction. Chem. Mater. 30, 1032–1044 (2018).

Zhou, S. et al. Pd single‐atom catalysts on nitrogen‐doped graphene for the highly selective photothermal hydrogenation of acetylene to ethylene. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900509 (2019).

Chen, C. et al. Zero-Valent Palladium single-atoms catalysts confined in black phosphorus for efficient semi-hydrogenation. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008471 (2021).

Jia, H. et al. Site-selective growth of crystalline ceria with oxygen vacancies on gold nanocrystals for near-infrared nitrogen photofixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5083–5086 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Selective CO2 Photoreduction to CH4 via Pdδ+‐Assisted Hydrodeoxygenation over CeO2 Nanosheets. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 61, e202203249 (2022).

Shimizu, K. I., Maruyama, R., Komai, S. I., Kodama, T. & Kitayama, Y. Pd-sepiolite catalyst for Suzuki coupling reaction in water: structural and catalytic investigations. J. Catal. 227, 202–209 (2004).

Lin, H. et al. Immobilization of a Pd (ii)-containing N-heterocyclic carbene ligand on porous organic polymers: efficient and recyclable catalysts for Suzuki-Miyaura reactions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 11, 3676–3680 (2021).

Baran, T. et al. Production of magnetically recoverable, thermally stable, bio-based catalyst: Remarkable turnover frequency and reusability in Suzuki coupling reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 331, 102–113 (2018).

Hai, X. et al. Engineering local and global structures of single co atoms for a superior oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 10, 5862–5870 (2020).

Trobe, M. & Burke, M. D. The molecular industrial revolution: automated synthesis of small molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4192–4214 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. High-speed circulation flow platform facilitating practical large-scale heterogeneous photocatalysis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 28, 1964–1970 (2024).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Du, Y. et al. XAFCA: a new XAFS beamline for catalysis research. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 22, 839–843 (2015).

Ravel, B. & Newvillea, M. ATHENA and ARTEMIS. Int. Tables Crystallogr. I 6.1, 723–727 (2024).

VandeVondele, J. et al. Quickstep: fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput. Phys. Commun. 167, 103–128 (2005).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Tang, Y., Wang, Y. G. & Li, J. Theoretical investigations of Pt1@CeO2 single-atom catalyst for CO oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 11281–11289 (2017).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

Tang, W., Sanville, E. & Henkelman, G. A grid-based Bader analysis algorithm without lattice bias. J. Phys. Condens Matter 21, 084204 (2009).

Dronskowski, R. & Blochl, P. E. Crystal orbital Hamilton populations (COHP): energy-resolved visualization of chemical bonding in solids based on density-functional calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 8617–8624 (1993).

Deringer, V. L., Tchougréeff, A. L. & Dronskowski, R. Crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 5461–5466 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support from the NRF, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under the Competitive Research Program Award (NRF-CRP29-2022-0004), MOE Tier 2 grants (MOE-T2EP10221-0005, MOE-T2EP10123-0004, MOE-T2EP10223-0004), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) under MTC Individual Research Grants (Project ID M22K2c0082), SUSTech-NUS joint research program (A-8002269-00-00, A-8002269-01-00, A-8002269-02-00) and Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province (Grant number BZ2022056). XAFS experiments were performed at SPring-8 under proposal NOs. 2024A1566 and 2021B2103. Y.X and D.W are grateful for financial support from the NAP-SUG from NTU, AcRF Tier 1 grants (RG81/22) and AcRF Tier 2 grants (MOE-T2EP10123-0003) from MOE, Singapore. Computational resources are supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering at SUSTech and the CHEM high-performance supercomputer cluster (CHEM-HPC) located in the Department of Chemistry, SUSTech.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Lu. supervised the project and organized the collaboration. J.S., X.H. and J.Lu. conceived the research and designed the experiment. J.S. performed materials synthesis and characterization with the supervision of X.H., and J.Lu. J.S., D.T. and Y.Y. performed the activity test and organic synthesis. L.M., S.X., and P.H. performed the XAFS measurement and structure analysis. G.W. carried out theoretical calculations under the supervision of Y.-G.W. D.T. and Y.Y. performed the flow synthesis under the supervision of J.W. R.M. synthesized CeO2 with different crystal facets. Y. X performed operando XAFS measurements and analysis under the supervision of D.W. Y.T., Q.C., and J.C., helping optimize schematics. X.Z., H. Lin., X.F. and H. Li. performed electron microscopy experiments and data analysis. J.L. Li and J.H. Li created videos. Q.H., J.Li. and Q.-H.Y. contributed to the scientific discussion. All authors contributed to the discussion of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Abdulaziz W. Alherz, Yaqiong Su and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, J., Wang, G., Tian, D. et al. Defying the oxidative-addition prerequisite in cross-coupling through artful single-atom catalysts. Nat Commun 16, 3223 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58579-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58579-8