Abstract

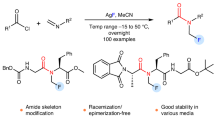

N-CF3 amides are promising targets for pharmaceutical and agrochemistry. Unfortunately, there is a defluorination problem of N-CF3 amine starting materials when using common amide bond formation method. Recently, elegant alternative approaches emerged. However, none have used the well known amidyl radical chemistry to directly prepare N-CF3 amides. We describe here a convenient preparation of N-(N-CF3 imidoyloxy) pyridinium salts and their applications as efficient trifluoromethylamidyl radical precursors in photocatalytic trifluoromethylamidations of (hetero)arenes, alkenes, alkynes, silylenol ethers, and isocyanides. The rapid construction of diverse N-CF3 amides, particularly the synthesis of cyclic N-CF3 amides, demonstrates the uniqueness and flexibility of the method. This method is expected to provide a platform for directly synthesizing N-CF3 amides and to inspire the discovery of more redox molecular systems that can handle challenging trifluoromethylamidations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

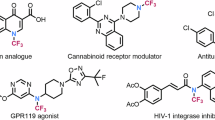

Trifluoromethyl (CF3) modification has become an important strategy for discovering functional molecules, as the introduction of the CF3 group can adjust the biophysical properties of the parent molecules, such as solubility, basicity, lipophilicity, permeability, and metabolic stability1,2,3. Amides play a prominent role in the fields ranging from drug design, agrochemical industry to organic synthesis4,5. To modify amide molecules by introducing the CF3 group onto the amide N atom is of interest6. However, the limitations of synthetic method greatly hinder the application of N-CF3 amides.

The preparation of N-CF3 amides using traditional amide bond formation method remains challenging due to the ease of defluorination when dealing with primary/secondary N-CF3 amine starting materials7,8. Solving such problem and seeking alternative approaches are currently the research focuses in this field. With the development of basic strategies for constructing the NCF3 unit9,10,11, including fluorine exchange strategy12,13,14,15,16,17 and N-trifluoromethylation strategy18,19,20,21,22,23, significant progress has recently been made in the preparation of N-CF3 amides. In 2020, Fang and Li synthesized N-CF3 tertiary amides via Ag-mediated oxidative N-trifluoromethylation of secondary amides (Fig. 1A, a)24. Such N-trifluoromethylation route is straightforward and simple, but only this method has been applied in synthesis, as there is still a lack of effective methods for bonding the CF3 onto the N atom. By comparison, the step-by-step synthesis of N-CF3 tertiary amides developed by Schoenebeck in 2019 presents a wide range of applications. Starting from isothiocyanates, AgF and bis(trichloromethyl)carbonate (BTC), N-CF3 carbamoyl fluorides were synthesized at first via a fluorination and acylation sequence, in which they utilized Ag+ to stabilize the in situ formed NCF3 anion for avoiding defluorination. Then the cross-coupling reaction of N-CF3 carbamoyl fluorides with Grignard reagents was carried out to afford diverse N-CF3 tertiary amides (Fig. 1A, b1)6. Moreover, the synthesis of N-CF3 alkynamides and N-CF3 formamides could also be achieved from N-CF3 carbamoyl fluorides, respectively25,26. Soon after, a one-pot synthesis of N-CF3 amides was reported by Toste and Wilson, which was realized by direct acylation of similar Ag+-stabilized NCF3 anion with carboxylic acid halides (Fig. 1A, b2)27.

As described above, Ag+-stabilized NCF3 anion can act as an in situ generated NCF3 transfer species for constructing N-CF3 compounds. Recently, stable NCF3 transfer precursors have emerged for practical applications, such as N3CF3 reported by Beier as the precursor for trifluoromethyl nitrene28, and N-protected N-CF3 hydroxylamine esters reported by Huang and Xu as the precursor for NCF3 radical29. The latter reagents were prepared through oxidative N-trifluoromethylation24 of pre-synthesized N-Boc/Cbz hydroxylamine esters. Taking these N-CF3 N-O reagents as the N-CF3 amidyl radical source, a set of radical cross-coupling reactions have been established. Among them, the C-H trifluoromethylamination of arenes delivered N-Boc/Cbz N-CF3 aromatic amines. After deprotection, the in situ generating N-CF3 amines could be further converted into N-CF3 tertiary amides by using the synthetic procedures developed by Schoenebeck mentioned above6, including fluoroformylation with BTC/AgF and cross-coupling with Grignard reagents (Fig. 1A, c1). It is worth noting that, unlike NCF3 anion6,30, such NCF3 radical-involved process has less risk of defluorination. Meanwhile, the amidyl radical has diverse reactivity, indicating that a wide range of radical acceptors can be utilized, such as arenes, alkenes, alkynes and so on31,32. In fact, it provides a much more promising approach to N-CF3 amides. However, to the best of our knowledge, real trifluoromethylamidyl radical (Fig. 1A, c2) directly used for constructing N-CF3 amides has not been reported yet.

In our ongoing interest in developing synthetic methods of N-CF3 compounds33,34,35,36, we have recently established a synthetic method for N-CF3 imidate esters via the reaction of N-CF3 nitrilium ions (Fig. 1B) and alcohols. In continuing investigations, we tried to prepare N-CF3 O-N imidates (1) by expanding alcohol-based reaction partners to N-oxide-type O-nucleophiles (Fig. 1B). Given great advances in the use of redox-active O-N reagents as O-centered radical source37,38,39,40,41,42, we further envisioned a generation of imidoyloxy radical (O-radical) from 1 via the fragmentation of the O-N bond under photoredox catalysis, and its cross-coupling reactions in the form of trifluoromethylamidyl radical resonance hybrid (N-radical)43,44, which would be for developing alternative route to N-CF3 amides. However, the first step in utilizing such synthetic strategy is to address the selectivity issue of the O-N bond cleavage, that is, to control the formation of imidoyloxy radical instead of imidoyloxy anion under photocatalysis (Fig. 1B). Suitable redox active N-CF3 N-O imidates are indeed necessary for efficient formation of amidyl radical and the development of trifluoromethylamidation reaction. Herein, we would like to report a kind of N-CF3 amidyl radical precursors for directly preparing diverse N-CF3 tertiary amides through coupling of them with (hetero)arenes, functionalized alkenes and isonitriles (Fig. 1B, a and b). It is worth noting that, taking advantage of the structural diversity of nitrile starting materials, we can also synthesize interesting N-CF3 cyclic amides (Fig. 1B, c), demonstrating the uniqueness and flexibility of the method.

Results

Screening and synthesis of N-CF3 amidyl radical precursors

Initially, the preparation of N-CF3 imidate ester-based O-N reagents (1) (Fig. 2A) was tested through nucleophilic addition reaction of in situ formed N-CF3 nitrilium ions by employing both hydroxylamine derivatives and heterocyclic N-oxides as O-nucleophiles. Considering that the reductive fragmentation of O-N reagents containing electron-deficient N-leaving group is more conducive to the release of O-radical under photoredox catalysis41, we focused on the synthesis of 1 with phthalimidyl group and pyridyl group. Although the nucleophilic addition is methodological inefficient in these cases, several N-hydroxyphthalimides (NHPI) and pyridine-N-oxides were delightfully found to react with N-CF3 nitrilium ion derived from acetonitrile, affording desired imidates (1a-e) in good yields (Fig. 2A). As a result, we decided to evaluate the reactivity of N-O reagents (1a-e) as potential trifluoromethylamidyl radical source in the trifluoromethylamidation of arenes and selected 4-tert-butylanisole (2a) as the model substrate (Fig. 2A). By screening of reaction conditions including the photocatalyst, the light, the solvent, and the ratio of the substrates (see Supplementary Table S1), the reactions of NHPI imidates (1a and 1b) with 2a were proven to be ineffective (Fig. 2A, Entries 1 and 2). No desired trifluoromethylamidated product (3a) was obtained except that a species, assigned as N-CF3 secondary amide (4a), was detected by both 19F NMR (−57.3 ppm) and MS ([M + H]+ = 128.0313)45. The formation of 4a may originate from two undesired competing processes: the protonation of unwanted imidoyloxy anion (Fig. 2B, path a); or undesired H-abstraction of imidoyloxy radical (Fig. 2B, path b). By comparison, pyridinium imidates (1c-e) could furnish desired 3a with satisfactory yield in DCM at room temperature in the presence of 1 mol% Ir(dFppy)3 under blue LEDs irradiation, while also producing 4a (Fig. 2A, Entries 3-5). Among these N-O reagents, 1e is a more proper candidate for the trifluoromethylamidation. 1c and 1 d produced more 4a, showing that pyridinium imidates containing electron-donating substituent on the pyridine ring are more inclined to release undesired imidoyloxy anion by reductive fragmentation. It is worth noting that no O-coupling product of imidoyloxy radical was detected. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) studies of both reagents (1a-e) and photocatalyst Ir(dFppy)3 were then conducted to understand such redox process (see Supplementary Fig. 1-6). Obviously, 1e with a reduction potential of −0.67 V can be reduced by the Ir-catalyst (−0.8 V) under current conditions. Furthermore, mechanistic studies by performing the reaction with radical scavenger revealed that this trifluoromethylamidation reaction likely proceeded through a radical pathway (Fig. 2A, Entries 6 and 7).

A Synthesis of N-CF3 O-N imidates 1 from acetonitrile for radical trifluoromethylamidation of arene 2a. B Possible pathways for the formation of by-product 4a. C Preparation of N-CF3 imidoxyl pyridinium salts from diverse nitriles. aReaction conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), 2a (0.3 mmol), Ir(dFppy)3 (0.001 mmol), DCM (3 mL), Blue LEDs, under N2, rt, 12 h, 19F NMR yields using PhCF3 as an internal standard. bReaction conditions: step1: PhICF3Cl (1.5 mmol), RCN (3.5 mL), 80 °C, 2 h; step 2: pyridine-N-oxide (1.0 mmol), NaX (2.0 mmol), isolated yields. cReaction conditions: N-CF3 imidoyl chlorides (1.1 mmol), pyridine-N-oxide (1.0 mmol), NaX (2.0 mmol), MeCN (4 mL), RT, 12 h. BHT Butylated hydroxytoluene, TEMPO 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidinyloxy.

After determining N-CF3 imidoxyl pyridinium scaffold can serve as a suitable trifluoromethylamidyl radical source, we tried to prepare a series of N-(N-CF3imidoxyl)pyridinium salts (1) through nucleophilic addition reaction of the in situ formed N-CF3 nitrilium salts34 with pyridine-N-oxide. By screening reaction conditions, 1e and 1 f could be obtained directly from nitriles in one-pot two-step procedures (Fig. 2C, method A). 11 mmol scaled-up reaction was proved to have similar efficiency, which afforded pyridinium salts (1e) in 96% isolated yield (3.69 g). As for those N-CF3 imidoxyl pyridinium salts (1) derived from nitriles with high viscosity or solid nitriles, N-CF3 imidoyl chlorides35 were required to be pre-synthesized as the precursor of N-CF3 nitrilium salts (Fig. 2C, method B). In these cases, a broad range of alkyl, vinyl and aryl N-CF3 imidoyl chlorides worked well and afford structurally diverse N-O reagents (1g-y) in excellent yields. Generally, these reagents are white solids, which exhibit complete air tolerance under ambient conditions. X-ray diffraction analysis of compound (1i) unambiguously confirmed its structure.

Scope of the trifluoromethylamidation of (hetero)arenes

Next, the scope of (hetero)arenes in the trifluoromethylamidation were investigated by using reagent (1e) as trifluoromethylamidyl radical precursor under the optimized conditions (Fig. 2A, Entry 5, also see Supplementary Table S1). Amidyl radicals have electrophilic nature, which often lead to low reaction efficiency with electron deficient radical acceptors. That’s indeed the case. In our experiments, electron-rich (hetero)arenes generally showed more reactive than electron-deficient ones. In the cases of those reaction partners with electron-deficient groups or without stronger electron-donating groups, sluggish reactions usually resulted in more 4a likely because the generated imidoyloxy radical has more opportunity for the H-abstraction from the reaction mixture (see Supplementary Fig. 9). As described in Fig. 3, among the tested arenes (2a-j) with one or more electron-donating groups, most provided amide products (3a, 3c-f and 3h-j) with a yield of over 70%, while benzene (2b), 4-bromoanisole (2 g) and p-xylene (2 h) gave 3b, 3 g and 3 h in 43%, 44% and 50% yields, respectively, along with the formation of by-product 4a with a yield of about 40%. The reaction of 2a with 1e could be performed on a gram scale (10 mmol) to afford 3a in 65% yield (1.89 g). The C-H trifluoromethylamidations of naphthalene (2k) and 2-methoxynaphthalene (2 l) also proceeded smoothly, affording N-CF3 amides (3k and 3 l) in excellent yields. As for heterocyclic substrates, including pyrroles (2m-o), furan (2p), thiophenes (2q-s), indoles (2t and 2 u), benzofuran (2 v), benzothiophene (2w), coumarin (2x) and 2,6-dimethoxy pyridine (2 y), they all regioselectively provided trifluoromethylamidated products (3m-y) with moderate to excellent yields ranging from 46% to 94%. It should be pointed out that the tested heterocycles with carbonyl and ester groups are compatible with the reaction though benzene derivatives with strong electron-deficient groups were not suitable radical acceptors as mentioned above. By comparison, those arenes containing free NH or OH groups, as well as 3,5-dimethoxy pyridine were sensitive to the N-O reagent (1) and usually resulted in complex mixture (see Supplementary Fig. 9)39. In addition, indole (2t) without 3-substituent produced 3t with lower yield. To further illustrate the practice ability of the method, we investigated the late-stage functionalization of several bioactive molecules and drug derivatives. It was found that naproxen (2z), L-menthol (2aa), cholesterol (2ab) derivatives, and nature products including caffeine (2ac), pentoxifylline (2ad), 1,3-dimethyluracil (2ae), they all tolerated the reaction, giving 3z-ae in 34-87% yields, respectively. In addition, alkyl imidoxyl pyridinium salts (1 f, 1 g) and vinyl imidoxyl pyridinium salt (1 h) were used as NCF3 amidyl radical source to react with 2 m. As a result, corresponding products (3af-ah) were obtained in 73-84% yields.

Then, aromatic imidoxyl pyridinium salts were chosen to explore their reactivity in the C-H trifluoromethylamidation of (hetero)arenes. As described in Fig. 3, when treating 1i derived from benzonitrile with 1,4-disubstituted arene (2a), 1,3,5-trisubstituted arene (2i), or heteroarenes (2p and 2q) under identical reaction conditions, to our delight, N-benzoyl trifluoromethylamidyl radical was efficiently generated and smoothly reacted as the N-centered radical with the tested arene substrates, affording N-CF3 benzamide products (3ai-al) in good yields. The structure of 3al was confirmed by its X-ray analysis. The reactivity of different aromatic N-CF3 imidoxyl pyridinium salts were then evaluated in the reaction with 2 m. It was found that phenyl substituted N-O reagents (1j-v) with a diverse array of functional groups delivering desired 3am-az in 70-92% yields. 2-Naphthylimidoxyl pyridinium salt (1w), as well as 2-thienyl and 2-benzofuryl ones (1x and 1 y) were also proven to be tolerated to this reaction, giving products (3ba-bc) in good yields.

Extended applications of radical trifluoromethylamidations

After establishing aromatic C-H trifluoromethylamidation, we decided to further expand the applications of this synthetic method by exploring the reactions of 1 with other radical acceptors. As presented in Fig. 4, trifluoromethylamidation and intramolecular arylation of 2-isocyanobiphenyls (5a and 5b) with 1e gave N-trifluoromethylamido phenanthridine derivatives (6a and 6b) in 58% and 64% yields, respectively (Fig. 4A). When employing silylenol ethers (7a and 7b) as alkene substrates in the reaction with 1e, α-trifluoromethylamido ketones (8a and 8b) were obtained as the final product (Fig. 4B). In addition, the reaction of allylsilane (9) with 1i furnished N-trifluoromethylallylamide (10) in 85% yield (Fig. 4C). The NCF3 radical-initiated lactonization/lactamidation of 2,2-dimethyl-4-phenylpent-4-enoic acid (11)/2,2-dimethyl-4-phenyl-N-tosylpent-4-enamide (13) were also tested, providing corresponding cyclic products (12 and 14) in excellent yields, respectively (Fig. 4D, E). Finally, sequential trifluoromethylamidation and 1,2-migration reaction of 1,1-diphenylprop-2-en-1-ol (15) and 1e was carried out and afforded β-trifluoromethylamido ketone (16) in 60% yield (Fig. 4F).

A Radical trifluoromethylamidations of compounds 5. B Radical trifluoromethylamidations of compounds 7. C Radical trifluoromethylamidation of compound 9. D Radical trifluoromethylamidation of compound 11. E Radical trifluoromethylamidation of compound 13. F Radical trifluoromethylamidation of compound 15. General reaction conditions: Ir(dFppy)3 (0.003 mmol), DCM (9 mL), Blue LEDs, under N2, RT, 12 h, isolated yields. a1e (0.3 mmol), 5 (0.9 mmol). b1e (0.3 mmol), 7 (0.9 mmol). c1i (0.3 mmol), 9 (0.9 mmol). d1e (0.45 mmol), 11 (0.3 mmol). e1e (0.45 mmol), 13 (0.3 mmol). f1e (0.3 mmol), 15 (0.9 mmol).

Scope of the aryltrifluoromethylamidation of alkenes/alkynes

Bifunctionalization of alkenes presents important applications in preparing densely functionalized organics46. Encouraged by the successful development of intramolecular trifluoromethylamidative bifunctionalization of alkenes (Fig. 4D-F), we turned to investigate their intermolecular versions. Thus, the oxytrifluoromethylamidation and the thiocyanotrifluoromethylamidation were initially attempted with both aliphatic and aromatic trifluoromethylamidyl radical precursors (1e and 1i), respectively. However, when 1-decene (17a) was treated with 1e or 1i in MeOH under basic and photoredox catalytic conditions, no desired bifunctionalized product was obtained. Similarly, the attempt on the thiocyanotrifluoromethylamidation of 17a with KSCN also failed. Both 1e and 1i were found to be sensitive to basic reaction condition. Interestingly, in the reaction mixture of 17a and 1i, an intramolecular aryltrifluoromethylamidation product, namely N-CF3 3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-one (18a) (Fig. 5) was isolated and identified. In the case of 1-octyne (19a) as the substrate toward above identical reaction conditions, N-CF3-isoquinolin-1(2H)-one (20a) was also yielded as cyclic product. As a class of lactams, isoquinolin-1(2H)-one derivatives are frequently found in natural products and pharmaceuticals47,48. Given that CF3 modification can enhance the bioactivity of molecules, N-CF3 lactams are of highly desired in both synthetic and medicinal chemistry. Unfortunately, their synthetic method is limited. In 2021, Schoenebeck reported an access to N-CF3 quinolones and N-CF3 oxindoles through the cyclization of pre-synthesized N-CF3 alkynamides25. By comparison, the radical trifluoromethylamidative cyclization method described here utilizes 1 as a four-component synthon containing NCF3 in the [4 + 2] cyclization with alkenes/alkynes and takes advantage of the structural characters of N-CF3 amidyl radical precursors (1). As starting materials, both nitriles and alkenes/alkynes are readily available, which allows the synthesis of N-CF3 cyclic amides with diverse structures. Thus, we carefully screened the conditions for such cyclization (see Supplementary Table S2). As a result, [4 + 2] cyclization of 17a and 1i was found to deliver 18a in 66% yield when three equivalents of 17a were employed in the presence of 1 mol% Ir(dFppy)3 in DCM under Blue LEDs irradiation at room temperature. It should be pointed out that, despite many efforts to screen the reaction conditions, such trifluoromethylamidative cyclization was inevitably accompanied by the formation of N-CF3 secondary amide (4b)49,50 generated from 1i, which makes it difficult to improve the yield of expected 18a. Next, we investigated the alkene scope under relatively better reaction conditions mentioned above. As shown in Fig. 5, all tested unactivated mono-substituted alkenes could furnish cyclic products (18a-l) in 52-78% yields. The substrates based on tosylate, phthalimide and carboxylic ester (17e-l) were compatible with the conditions. Poly-substituted alkenes, including 1,1-disubstituted alkenes (17m-o), 1,2-disubstituted alkenes (17p-r) and trisubstituted alkene (17 s) could also smoothly afford corresponding cyclic amide products (17m-s) in moderate to good yields. Among them, asymmetric internal alkenes (17p) afforded a mixture of regioisomeric products (18p and 18p’) with a ratio of 1.5 to 1. However, tetrasubstituted alkenes (17t) could not give desired N-CF3 3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-one (18t). Furthermore, several drug molecules, including L-menthol (17 u), febuxostat (17 v), ibuprofen (17w), fenofibric acid (17x) and isoxepac (17 y) were tested and provided N-CF3 3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-ones (18u-y) in 54-79% yields. It should be noted that styrene derivatives were not suitable substrates likely because the involved radical adducts, benzyl radicals, often engage in unproductive side reactions, such as oligomerization and isomerization. As for electron-deficient alkenes, they were also not compatible with this intramolecular aryltrifluoromethylamidation and gave complex mixture, among which by-proudct 4b could be detected. (see Supplementary Fig. 10)

Next, we turned our attention to the trifluoromethylamidative cyclization of alkynes. As shown in Fig. 5, a wide variety of alkynes, including terminal alkyl alkynes (19a-e) and aryl alkynes (19f-l), afforded N-CF3 isoquinolin-1(2H)-ones (20a-l) in moderate to good yields under identical reaction conditions. Among them, aryl alkynes substrates bearing electron-donating groups, such as –Me, –OMe, exhibiting superior reactivity compared to those bearing electron-withdrawing groups. The molecular structure of 20 g was established unequivocally by X-ray crystal structure determination. Furthermore, internal alkynes (19 m and 19n) could also undergo such radical cyclization with good yields. This cyclization method has also been successfully applied to the modification of bioactive molecules. In particular, N-CF3 trotabresib51 (20o) was obtained to demonstrate the practical application of the developed approach in drug discovery. Finally, we explored the scope of N-CF3 aryl imidoxyl pyridinium salts using alkyne (19 g) as the reaction partner. It was found that the cyclizations of all tested 1j-1l, 1q, 1 s and 1 v delivered N-CF3 isoquinolin-1(2H)-ones (20p-u) in 54-70% isolated yields.

Plausible reaction mechanism

Based on previous literatures39,44 and our experimental results, a plausible mechanism was proposed using 1e as the trifluoromethylamidyl radical source and the trifluoromethylamidation of 2b as an example (Fig. 6A). Initially, IrIII(dFppy)3 is excited to a triplet state IrIII(dFppy)3* under blue LEDs illumination. A SET process between IrIII(dFppy)3* and 1e occurs, providing IrIV(dFppy)3(PF6) and radical (Int-I). N-CF3 imidoyloxy radical (Int-II’) is then generated from the fragmentation of Int-I along with the release of pyridine. In the following step, the trifluoromethylamidyl radical (Int-II), a resonance hybrid of O-centered radical (Int-II’)44, serves as a real reactive N-centered radical to attack benzene, leading to adduct Int-III. Finally, a SET process between Int-III and IrIV, followed by deprotonation, delivers trifluoromethylamidated product (3b) with the recovery of IrIII(dFppy)3 for the next catalytic process. It is worth noting that in our reaction, the trifluoromethylamidyl radical (Int-II) takes priority over the imidoyloxy radical (Int-II’) in coupling with benzene. This selectivity encouraged us to conduct the density functional theory (DFT) calculations to compare the reactivity of two resonant radicals (Int-II and Int-II’) in the reaction with benzene. As shown in Fig. 6B, Int-III is formed via TS with a barrier of 7.5 kcal mol–1, whereas the generation of Int-III’ via TS’ has to overcome a barrier of 15.4 kcal mol–1. Obviously, the barrier of the C-N coupling is lower than that of the C-O coupling, demonstrating that the C-N coupling process is more favorable. In addition, the site selectivity of C-H trifluoromethylamidation of 2c using 1e was studied by DFT calculations. As shown in Fig. 6C, the formation of Int-III-para by the addition of trifluoromethylamidyl radical (Int-II) to 2c via TS-pata requires the lowest energy, which suggested that para-3c is main product.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a trifluoromethylamidation strategy for direct synthesis of N-CF3 amides. Starting from efficient N-trifluoromethylation reaction of nitriles using PhICF3Cl, O-N reagents based on N-CF3 imidoyl easters have been synthesized and developed as the precursor of trifluoromethylamidyl radical. With these trifluoromethylamidating reagents, a variety of trifluoromethylation reactions have been developed. These reactions are robust, can occur under mild photoredox-catalytic conditions, and exhibit wide application scopes of substrates. N-CF3 amides with various functional groups are formed in a modular fashion. The use of the method for late-stage modification of drugs has also been investigated. More importantly, the uniqueness of the method has been presented by the synthesis of N-CF3 lactams. We expect that this method will not only provide a versatile and flexible preparation platform for N-CF3 amides but also inspire the discovery of more redox molecular systems that can handle challenging trifluoromethylamidations.

Methods

General procedure for the synthesis of N-(N-CF3imidoxyl)pyridinium salts

Method A: A 10 mL Schlenk tube was charged with PhICF3Cl (1.5 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), RCN (3.5 mL) and a stir bar under N2. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 2 h and cooled to room temperature. pyridine-N-oxide (1.0 mmol) and NaX (2.0 mmol, 2 equiv.) were added for reacting additional 12 h at room temperature. Then, resulting mixture was added to H2O (15 mL) and extracted with DCM (20 mL × 3). The organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, followed by adding diethyl ether (20 mL). The resulting precipitate was washed by diethyl ether to give the desired products.

Method B: A 10 mL Schlenk tube was charged with N-CF3 imidoyl chloride (1.1 mmol, 1.1 equiv.), pyridine-N-oxide (1.0 mmol), NaX ((2.0 mmol, 2 equiv.) and a stir bar in MeCN (3 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Then, resulting mixture was added to H2O (15 mL) and extracted with DCM (20 mL × 3). The organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, followed by adding diethyl ether (20 mL). The resulting precipitate was washed by diethyl ether to give the desired products.

General procedure for the trifluoromethylamidations of arenes

A 35 mL flask was charged with 1 (0.3 mmol), Ir(dFppy)3 (0.003 mmol, 0.01 equiv.) and a stir bar under N2, then a solution of 2 (0.9 mmol, 3 equiv.) in DCM (9 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h under the irradiation of blue LED light (18 W) at room temperature. After the completion of the reaction as indicated by TLC, resulting mixture was added to H2O (15 mL) and extracted with DCM (20 mL × 3). The organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, and purified by silica column chromatography to give the desired products.

General procedure for the aryltrifluoromethylamidations of alkenes/alkynes

A 35 mL flask was charged with 1 (0.3 mmol), Ir(dFppy)3 (0.003 mmol, 0.01 equiv.) and a stir bar under N2, then a solution of 17 or 19 (0.9 mmol, 3 equiv.) in DCM (9 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h under the irradiation of blue LED light (18 W) at room temperature. After the completion of the reaction as indicated by TLC, resulting mixture was added to H2O (15 mL) and extracted with DCM (20 mL × 3). The organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, and purified by silica column chromatography to give the desired products.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source Data are provided with this paper. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2323804 for 1i, 2323803 for 3al, 1984011 for 4b, 2323802 for 20 g. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Purser, S., Moore, P. R., Swallow, S. & Gouverneur, V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 320–330 (2008).

Johnson, B. M., Shu, Y. Z., Zhuo, X. & Meanwell, N. A. Metabolic and pharmaceutical aspects of fluorinated compounds. J. Med. Chem. 63, 6315–6386 (2020).

Xiao, H., Zhang, Z., Fang, Y., Zhu, L. & Li, C. Radical trifluoromethylation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6308–6319 (2021).

Greenberg, A. et al. The Amide Linkage: Structural Significance in Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Materials Science (Wiley, 2000).

Pattabiraman, V. R. & Bode, J. W. Rethinking amide bond synthesis. Nature 480, 471–479 (2011).

Scattolin, T., Bouayad-Gervais, S. & Schoenebeck, F. Straightforward access to N-trifluoromethyl amides, carbamates, thiocarbamates and ureas. Nature 573, 102–107 (2019).

Klöter, G. & Seppelt, K. Trifluoromethanol (CF3OH) and trifluoromethylamine (CF3NH2). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 347–349 (1979).

Wang, L.-B. et al. General access to N−CF3 secondary amines and their transformation to N−CF3 sulfonamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212115 (2022).

Milcent, T. & Crousse, B. The main and recent syntheses of the N-CF3 motif. C. R. Chim. 21, 771–781 (2018).

Lei, Z., Chang, W., Guo, H., Feng, J. & Zhang, Z. A brief review on the synthesis of the N-CF3 motif in heterocycles. Molecules 28, 3012–3037 (2023).

Crousse, B. Recent advances in the syntheses of N-CF3 scaffolds up to their valorization. Chem. Rec. 23, e202300011 (2023).

Klauke, E. Preparation and properties of substances with N- or S-perhalogenomethyl groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 5, 848–848 (1966).

Scattolin, T., Deckers, K. & Schoenebeck, F. Efficient synthesis of trifluoromethyl amines through a formal umpolung strategy from the bench-stable precursor (Me4N)SCF3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 221–224 (2017).

Yu, J., Lin, J.-H. & Xiao, J.-C. Reaction of thiocarbonyl fluoride generated from difluorocarbene with amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 16669–16673 (2017).

Liang, S. et al. One-pot synthesis of trifluoromethylamines and perfluoroalkyl amines with CF3SO2Na and RfSO2Na. Chem. Commun. 55, 8536–8539 (2019).

Wu, J.-Y. et al. N-Halosuccinimide enables cascade oxidative trifluorination and halogenative cyclization of tryptamine-derived isocyanides. Nat. Commun. 15, 8917 (2024).

Song, H. et al. Efficient N-trifluoromethylation of amines with carbon disulfide and silver fluoride as reagents. CCS Chem. 7, 381–391 (2025).

Umemoto, T., Adachi, K. & Ishihara, S. CF3 Oxonium Salts, O-(Trifluoromethyl)dibenzofuranium salts: in situ synthesis, properties, and application as a real CF3+ species reagent. J. Org. Chem. 72, 6905–6917 (2007).

Niedermann, K. et al. A ritter-type reaction: direct electrophilic trifluoromethylation at nitrogen atoms using hypervalent iodine reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 1059–1063 (2011).

Niedermann, K. et al. Direct electrophilic N-trifluoromethylation of azoles by a hypervalent iodine reagent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 6511–6515 (2012).

Zheng, G., Ma, X.-L., Li, J.-H., Zhu, D.-S. & Wang, M. Electrophilic N-trifluoromethylation of N–H ketimines. J. Org. Chem. 80, 8910–8915 (2015).

Brantley, J. N., Samant, A. V. & Toste, F. D. Isolation and reactivity of trifluoromethyl iodonium salts. Acs. Cent. Sci. 2, 341–350 (2016).

Blastik, Z. E. et al. Azidoperfluoroalkanes: Synthesis and Application in Copper(I)-Catalyzed Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 346–349 (2017).

Zhang, Z.-Z. et al. Silver-mediated N-trifluoromethylation of amides and peptides. Chin. J. Chem. 38, 924–928 (2020).

Nielsen, C. D.-T., Zivkovic, F. G. & Schoenebeck, F. Synthesis of N-CF3 alkynamides and derivatives enabled by ni-catalyzed alkynylation of N-CF3 carbamoyl fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 13029–13033 (2021).

Zivkovic, F. G., Nielsen, C. D.-T. & Schoenebeck, F. Access to N−CF3 formamides by reduction of N−CF3 carbamoyl fluorides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213829 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Synthesis of N-trifluoromethyl amides fromcarboxylic acids. Chem 7, 2245–2255 (2021).

Baris, N. et al. Photocatalytic generation of trifluoromethyl nitrene for alkene aziridination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202315162 (2023).

Liu, S., Huang, Y.-G., Wang, J., Qing, F.-L. & Xu, X.-H. General Synthesis of N-trifluoromethyl compounds with N-trifluoromethyl hydroxylamine reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1962–1970 (2022).

Spennacchio, M. et al. A unified flow strategy for the preparation and use of trifluoromethyl-heteroatom anions. Science 385, 991–996 (2024).

Pratley, C., Fenner, S. & Murphy, J. A. Nitrogen-centered radicals in functionalization of sp2 systems: generation, reactivity, and applications in synthesis. Chem. Rev. 122, 8181–8260 (2022).

Zard, S. Z. Recent progress in the generation and use of nitrogen-centred radicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1603–1618 (2008).

Zhang, R. Z. et al. An N-trifluoromethylation/cyclization strategy for accessing diverse N-trifluoromethyl azoles from nitriles and 1,3-dipoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202110749 (2022).

Zhang, R. Z., Huang, W. Q., Zhang, R. X., Xu, C. & Wang, M. Synthesis of N-CF3 amidines/imidates/thioimidates via N-CF3 nitrilium ions. Org. Lett. 24, 2393–2398 (2022).

Zhang, R. Z., Gao, Y. F., Yu, J., Xu, C. & Wang, M. N-CF3 imidoyl chlorides: scalable N-CF3 nitrilium precursors for the construction of N-CF3 compounds. Org. Lett. 26, 2641–2645 (2024).

Gao, Y. F., Zhang, R. Z., Xu, C. & Wang, M. Controllable regioselective [3+2] Cyclizations of N-CF3 imidoyl chlorides and Ph3PNNC: divergent synthesis of N-CF3 triazoles. Org. Lett. 26, 5087–5091 (2024).

Chang, L., An, Q., Duan, L., Feng, K. & Zuo, Z. Alkoxy radicals see the light: new paradigms of photochemical synthesis. Chem. Rev. 122, 2429–2486 (2022).

Rçssler, S. L. et al. Pyridinium salts as redox-active functional group transfer reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9264–9280 (2020).

Beatty, J., Douglas, J., Cole, K. & Stephenson, C. A scalable and operationally simple radical trifluoromethylation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7919–7924 (2015).

Jelier, B. J. et al. Radical trifluoromethoxylation of arenes triggered by a visible-light-mediated N−O bond redox fragmentation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13784–13789 (2018).

Barthelemy, L., Tuccio, B., Magnier, E. & Dagousset, G. Alkoxyl radicals generated under photoredox catalysis: a strategy for anti-Markovnikov alkoxylation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13790–13794 (2018).

Mathi, G. R., Jeong, Y., Moon, Y. & Hong, S. Photochemical carbopyridylation of alkenes using N-alkenoxypyridinium salts as bifunctional reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2049–2054 (2020).

Esker, J. L. & Newcomb, M. Chemistry of amidyl radicals produced from N-hydroxypyridine-2-thione Imidate Esters. J. Org. Chem. 58, 4933–4940 (1993).

Li, L.-H., Wei, Y. & Shi, M. N-hydroxyphthalimide imidate esters as amidyl radical precursors in the visible light photocatalyzed C–H amidation of heteroarenes. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 1935–1940 (2021).

Til’kunnova, N. A., Gontar, A. F., Sizov, Yu. A., Bykhovskaya, E. G. & Knunyants, I. L. From Izvestiya Akademil Nauk SSSR, Seriya Khimicheskaya, 10, 2381–2383 (1977). Language: Russian, Database: CAPLUS

Jiang, H. & Studer, A. Intermolecular radical carboamination of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1790–1811 (2020).

Aly, Y. et al. A revision of the structure of the isoquinoline alkaloid thalflavine. Phytochemistry 28, 1967–1971 (1989).

Shang, X.-F. et al. Biologically active isoquinoline alkaloids covering 2014-2018. Med. Res. Rev. 40, 2212–2289 (2020).

Til’kunova, N. A. et al. From Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR, Seriya Khimicheskaya, 2820–2821 (1978). Language: Russian, Database: CAPLUS

Buettner, G. & Klauke, E. From Ger. Offen. (1973), DE 2215955 A1 19731004, Language: German, Database: CAPLUS

Moreno, V. et al. Trotabresib, an Oral Potent Bromodomain and Extraterminal Inhibitor, in Patients with high-Gradegliomas: A phase I, “Window-of-opportunity” Study. Neuro-Oncol. 25, 1113–1122 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (No. 20240101186JC to M.W. and No. 20230101031JC to C.X.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22471032 to M.W. and No. 22471033 to C.X.) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. directed the projects and wrote the manuscript. C.X. was responsible for mechanism discussions and calculations. R.Z.Z performed the experiments, obtained all data, and analyzed the results. Y.L. checked the manuscript and Supporting Information.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mingyou Hu, Chaozhong Li, Minyan Wang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, R.Z., Liu, Y., Xu, C. et al. Direct synthesis of N-trifluoromethyl amides via photocatalytic trifluoromethylamidation. Nat Commun 16, 4964 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60130-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60130-8