Abstract

Injuries to the brain result in tunable cell responses paired with stimulus properties, suggesting the existence of intrinsic processes that encode and transmit injury information; however, the molecular mechanism of injury information encoding is unclear. Here, using ATP fluorescent indicators, we identify injury-evoked spatiotemporally selective ATP dynamics, Inflares, in adult mice of both sexes. Inflares are actively released from astrocytes and act as the internal representations of injury. Inflares encode injury intensity and position at their population level through frequency changes and are further decoded by microglia, driving changes in their activation state. Mismatches between Inflares and injury severity lead to microglia dysfunction and worsening of injury outcome. Blocking Inflares in ischemic stroke in mice reduces secondary damage and improves recovery of function. Our results suggest that astrocytic ATP dynamics encode injury information and are sensed by microglia.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

27,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

209,00 € per year

only 17,42 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The raw data in each figure have been provided as Source Data Files. The raw data related to RNA sequencing results have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under accession codes SRR28644876 to SRR28644899. Other data reported in this paper will be shared by the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The imaging data were processed by MATLAB 2018 (MathWorks) and Imaris 9.7 (Oxford University) and fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ 1.53q (National Institutes of Health). The figures were organized using Adobe Illustrator 2023 (Adobe). The AQuA parameters used for identifying Inflare in this article, along with the analysis scripts based on AQuA results and the scripts for analyzing the sequencing results presented in this paper, can be accessed via GitHub at https://github.com/JingMiaoLab/NN82582C/tree/main.

References

Feigin, V. L., Barker-Collo, S., Krishnamurthi, R., Theadom, A. & Starkey, N. Epidemiology of ischaemic stroke and traumatic brain injury. Best. Pr. Res Clin. Anaesthesiol. 24, 485–494 (2010).

Ghajar, J. Traumatic brain injury. Lancet 356, 923–929 (2000).

Liesz, A. et al. DAMP signaling is a key pathway inducing immune modulation after brain injury. J. Neurosci. 35, 583–598 (2015).

Corps, K. N., Roth, T. L. & McGavern, D. B. Inflammation and neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 72, 355–362 (2015).

Loane, D. J. & Kumar, A. Microglia in the TBI brain: the good, the bad, and the dysregulated. Exp. Neurol. 275, 316–327 (2016).

Gadani, S. P., Walsh, J. T., Lukens, J. R. & Kipnis, J. Dealing with danger in the CNS: the response of the immune system to injury. Neuron 87, 47–62 (2015).

Di Virgilio, F., Sarti, A. C. & Coutinho-Silva, R. Purinergic signaling, DAMPs, and inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 318, C832–C835 (2020).

Mizuno, T., Kawanokuchi, J., Numata, K. & Suzumura, A. Production and neuroprotective functions of fractalkine in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 979, 65–70 (2003).

Dewitt, D. S. et al. Experimental traumatic brain injury elevates brain prostaglandin E2 and thromboxane B2 levels in rats. J. Neurotrauma 5, 303–313 (1988).

Malek Abrahimians, E., Carlier, V. A., Vander Elst, L. & Saint-Remy, J. M. MHC Class II-restricted epitopes containing an oxidoreductase activity prompt CD4(+) T cells with apoptosis-inducing properties. Front. Immunol. 6, 449 (2015).

Bouras, M., Asehnoune, K. & Roquilly, A. Immune modulation after traumatic brain injury. Front. Med. 9, 995044 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. P2X7 receptor inhibition improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 10, 821–827 (2004).

Ferrari, D. et al. Extracellular ATP triggers IL-1β release by activating the purinergic P2Z receptor of human macrophages. J. Immunol. 159, 1451–1458 (1997).

Honda, S. et al. Extracellular ATP or ADP induce chemotaxis of cultured microglia through Gi/o-coupled P2Y receptors. J. Neurosci. 21, 1975–1982 (2001).

Davalos, D. et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 752–758 (2005).

Haynes, S. E. et al. The P2Y12 receptor regulates microglial activation by extracellular nucleotides. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1512–1519 (2006).

Wu, Z. & Li, Y. New frontiers in probing the dynamics of purinergic transmitters in vivo. Neurosci. Res. 152, 35–43 (2020).

Wu, Z. et al. A sensitive GRAB sensor for detecting extracellular ATP in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 110, 770–782 (2022).

Galbraith, J. A. & Terasaki, M. Controlled damage in thick specimens by multiphoton excitation. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1808–1817 (2003).

Adrian, E. D. The impulses produced by sensory nerve-endings: part 4. Impulses from pain receptors. J. Physiol. 62, 33–51 (1926).

Ahn, S. J., Anrather, J., Nishimura, N. & Schaffer, C. B. Diverse inflammatory response after cerebral microbleeds includes coordinated microglial migration and proliferation. Stroke 49, 1719–1726 (2018).

Khurgel, M., Koo, A. C. & Ivy, G. O. Selective ablation of astrocytes by intracerebral injections of α-aminoadipate. Glia 16, 351–358 (1996).

Delaney, C. L., Brenner, M. & Messing, A. Conditional ablation of cerebellar astrocytes in postnatal transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 16, 6908–6918 (1996).

Yang, C. F. et al. Sexually dimorphic neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus govern mating in both sexes and aggression in males. Cell 153, 896–909 (2013).

Hagemeyer, N. et al. Microglia contribute to normal myelinogenesis and to oligodendrocyte progenitor maintenance during adulthood. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 441–458 (2017).

Dana, H. et al. Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. eLife 5, e12727 (2016).

Charlton, S. J. et al. PPADS and suramin as antagonists at cloned P2Y- and P2U-purinoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 118, 704–710 (1996).

Saez, J. C., Retamal, M. A., Basilio, D., Bukauskas, F. F. & Bennett, M. V. Connexin-based gap junction hemichannels: gating mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1711, 215–224 (2005).

Sehgal, P. et al. Inhibition of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca(2+)-ATPase by thapsigargin analogs induces cell death via ER Ca(2+) depletion and the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 19656–19673 (2017).

Yu, X. et al. Reducing astrocyte calcium signaling in vivo alters striatal microcircuits and causes repetitive behavior. Neuron 99, 1170–1187 (2018).

Agulhon, C. et al. Modulation of the autonomic nervous system and behaviour by acute glial cell Gq protein-coupled receptor activation in vivo. J. Physiol. 591, 5599–5609 (2013).

Hyzinski-Garcia, M. C., Rudkouskaya, A. & Mongin, A. A. LRRC8A protein is indispensable for swelling-activated and ATP-induced release of excitatory amino acids in rat astrocytes. J. Physiol. 592, 4855–4862 (2014).

Iglesias, R., Dahl, G., Qiu, F., Spray, D. C. & Scemes, E. Pannexin 1: the molecular substrate of astrocyte ‘hemichannels’. J. Neurosci. 29, 7092–7097 (2009).

Oya, M. et al. Vesicular nucleotide transporter is involved in ATP storage of secretory lysosomes in astrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 438, 145–151 (2013).

Chai, H. et al. Neural circuit-specialized astrocytes: transcriptomic, proteomic, morphological, and functional evidence. Neuron 95, 531–549 (2017).

Silverman, W., Locovei, S. & Dahl, G. Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C761–C767 (2008).

Poon, I. K. et al. Unexpected link between an antibiotic, pannexin channels and apoptosis. Nature 507, 329–334 (2014).

Brough, D., Pelegrin, P. & Rothwell, N. J. Pannexin-1-dependent caspase-1 activation and secretion of IL-1β is regulated by zinc. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 352–358 (2009).

Madry, C. et al. Effects of the ecto-ATPase apyrase on microglial ramification and surveillance reflect cell depolarization, not ATP depletion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E1608–E1617 (2018).

Howells, D. W. et al. Different strokes for different folks: the rich diversity of animal models of focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 30, 1412–1431 (2010).

Schaar, K. L., Brenneman, M. M. & Savitz, S. I. Functional assessments in the rodent stroke model. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2, 13 (2010).

Garcia-Rodriguez, C. et al. Probenecid, an old drug with potential new uses for central nervous system disorders and neuroinflammation. Biomedicines 11, 1516 (2023).

Purvis, J. E. & Lahav, G. Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell 152, 945–956 (2013).

Rolls, E. T. & Treves, A. The neuronal encoding of information in the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 448–490 (2011).

Gurdon, J. B. & Bourillot, P. Y. Morphogen gradient interpretation. Nature 413, 797–803 (2001).

Parodi, O., Combe, P. & Ducom, J. C. Temporal coding in vision: coding by the spike arrival times leads to oscillations in the case of moving targets. Biol. Cybern. 74, 497–509 (1996).

Dosch, M., Gerber, J., Jebbawi, F. & Beldi, G. Mechanisms of ATP release by inflammatory cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1222 (2018).

Ekstrand, M. et al. Depletion of ATP and glucose in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques. PLoS ONE 12, e0178877 (2017).

Iyer, S. S. et al. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20388–20393 (2009).

Chekeni, F. B. et al. Pannexin 1 channels mediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature 467, 863–867 (2010).

Zimmermann, H. Biochemistry, localization and functional roles of ecto-nucleotidases in the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 49, 589–618 (1996).

Fitz, J. G. Regulation of cellular ATP release. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 118, 199–208 (2007).

Eyo, U. B. et al. Neuronal hyperactivity recruits microglial processes via neuronal NMDA receptors and microglial P2Y12 receptors after status epilepticus. J. Neurosci. 34, 10528–10540 (2014).

Borst, A. & Theunissen, F. E. Information theory and neural coding. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 947–957 (1999).

Doron, A. et al. Hippocampal astrocytes encode reward ___location. Nature 609, 772–778 (2022).

Smith, S. J. Do astrocytes process neural information? Prog. Brain Res 94, 119–136 (1992).

Lines, J., Martin, E. D., Kofuji, P., Aguilar, J. & Araque, A. Astrocytes modulate sensory-evoked neuronal network activity. Nat. Commun. 11, 3689 (2020).

Kettenmann, H., Hanisch, U. K., Noda, M. & Verkhratsky, A. Physiology of microglia. Physiol. Rev. 91, 461–553 (2011).

Giaume, C. & McCarthy, K. D. Control of gap-junctional communication in astrocytic networks. Trends Neurosci. 19, 319–325 (1996).

Hammond, T. R. et al. Single-Cell RNA sequencing of microglia throughout the mouse lifespan and in the injured brain reveals complex cell-state changes. Immunity 50, 253–271 (2019).

Paolicelli, R. C. et al. Microglia states and nomenclature: a field at its crossroads. Neuron 110, 3458–3483 (2022).

Patriarchi, T. et al. Ultrafast neuronal imaging of dopamine dynamics with designed genetically encoded sensors. Science 360, eaat4422 (2018).

Jing, M. et al. An optimized acetylcholine sensor for monitoring in vivo cholinergic activity. Nat. Methods 17, 1139–1146 (2020).

Liu, F. et al. Changes in experimental stroke outcome across the life span. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 29, 792–802 (2009).

Hurn, P. D. & Macrae, I. M. Estrogen as a neuroprotectant in stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 20, 631–652 (2000).

Longa, E. Z., Weinstein, P. R., Carlson, S. & Cummins, R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 20, 84–91 (1989).

Wang, Y. et al. Accurate quantification of astrocyte and neurotransmitter fluorescence dynamics for single-cell and population-level physiology. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1936–1944 (2019).

Cui, Z. & Gong, G. The effect of machine learning regression algorithms and sample size on individualized behavioral prediction with functional connectivity features. Neuroimage 178, 622–637 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Li at Peking University for sharing the ATP1.0 sensor and related plasmid constructs; M. Luo and W. Ge at CIBR for sharing transgenic mice; Z. Cui at CIBR for valuable input and providing codes for the linear regression model; G. Yu from Virginia Tech for suggestions on data processing; Q. Guo and his team in the imaging core facility at CIBR for generous help in imaging experiments and data analysis; F. Zhao and his team in the vector core at CIBR for providing related AAV reagents. Some schematics were created using BioRender. This work was supported by the Project of Intergovernmental Science and Technology Innovative Cooperation, National Key Research and Development Program 2021YFE0116400 (M.J.); the STI2030-Major project 2021ZD0202200, subject 2021ZD0202203 (M.J.); The Beijing Nova Program Z20111000680000 (M.J.) and the Beijing Postdoctoral Science Foundation 2022-ZZ-026 (J.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. performed experiments related to ATP imaging and analysis of signal encoding. P.L. conducted experiments related to cell and molecular mechanism in vivo and MCAO-related experiments. J.L. carried out experiments related to signal decoding by microglia. Y.W. performed experiments for studying molecular mechanisms. C.W. designed and validated shRNA and sgRNA for genetic manipulations. R.W. performed the biochemical analysis of Panx1. Z.W. engineered the ATP1.0 sensor and made sensors expressing AAV constructs. M.J. conceived the project and performed brain slice experiments. All authors contributed to data analysis. Y.C. and M.J. wrote the manuscript with input from all the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks Alexandre Charlet, Adam Cohen, Amanda Sierra, and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The spatiotemporal property of microglia motility after FLA injury.

a. Illustration of experiments in which microglia motility was monitored in awake Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice in vivo. Focal laser ablation (FLA) was used to introduce local injury, and two-photon imaging was conducted to track microglia. b. Representative images of microglia prior to FLA (−FLA) or after FLA at indicated time points. c-e. Time-dependent changes of microglia migration after FLA. The migration index is quantified as the relative fluorescence change in the injury center (180 μm in diameter) over the whole image. The data of each mouse are shown in (c), and averaged data as well as the changes of migration index over time (Δmigration index) are plotted in (d) (n = 5 mice). The persistence is the time with effective signal over baseline in (e) (n = 5 mice). f. Illustration of the measurement of microglia polarity. g. The changes of microglia polarity to FLA at the single cell level. h. Illustration of the microglia directionality towards the injury center. The angle between the microglia polarity and injury is quantified. i. The microglia directionality before (−FLA) and after FLA (n = 366 microglia from 5 mice for −FLA; n = 313 microglia from 5 mice for +FLA). j. The relationship between microglia directionality and the distance of microglia to injury. The area with signal above baseline (−FLA) is defined as coverage and quantified (n = 5 mice). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. ***, p < 0.001; All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Characterization of injury-evoked ATP dynamics.

a. Illustration of ATP1.0 sensors that are specifically expressed on the membrane of neurons (up) or astrocytes (bottom) in detecting extracellular ATP. b. The ATP burst (fluorescence image, up) and Inflares (ROI, bottom) in neuronal or astrocytic ATP1.0-expressing mice. c. The ΔF/F0 of ATP bursts (up) and the number of Inflares (bottom) before and after FLA, in neuronal or astrocytic ATP1.0-expressing mice (n = 7 and 9 mice for neuronal and astrocytic expression). d. e, The comparison of Inflares in neuronal or astrocytic ATP1.0-expressing mice, with properties include ΔF/F0, size and duration analyzed (n = 7 and 9 mice for neuronal and astrocytic expression). f. The spatial distribution of basal fluorescence (F0) and fluorescence response (ΔF/F0) in Inflares. The Inflare ROIs are aligned with their center at position 0, and signals are plotted across 100 µm in space (n = 643 ROIs from n = 9 mice). g. The spatial distribution (left) and the correlation (right) of the ΔF/F0 with corresponding F0 in Inflares (n = 643 Inflares from n = 9 mice; r = −0.04 by Pearson correlation analysis). h. The comparison of ATP1.0 fluorescence inside or outside of Inflare ROIs (n = 9 mice). i. The fluorescence response (ΔF/F0 in pseudocolor, up) and regions of interest (ROIs, bottom) extracted for analysis. j. Comparison of the fluorescence response (ΔF/F0 integration, left), diameter (middle) and duration (right) between ATP bursts and Inflares. Group data from each mouse are shown on the left, with the distribution of individual Inflares summarized on the right (n = 643 Inflares from n = 9 mice). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Inflares are stereotyped and encode injury intensity by population frequency.

a, b. The comparison of Inflares across time, with the fluorescence change (ΔF/F0, left), size (middle) and duration (right) analyzed (n = 13 mice). c. The dimensional reduction analysis of Inflares recorded across time (n = 3980 Inflares from 13 mice). d-f. Similar as (a-c), except Inflares at different locations away from injury are analyzed (n = 3980 Inflares from 13 mice). g, h. Two-photon image of astrocytes co-expressing ATP1.0 and mRuby3. Two astrocytes were selected with their territory marked in magenta. Right, the generation of Inflares at selected time points in individual astrocytes. The positions of Inflare generation are extracted and overlayed. i. The Inflare number from single astrocytes within 2 hours after FLA. j. Illustration of the linear regression model to predict injury from Inflares. k. Parameters of Inflare properties and their weights in the successful-trained linear regression model. l. The relationship between measured damage and Inflare-predicted damage using shuffled frequency data in the linear regression model (n = 19 mice). Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Gradient distribution of Inflares encode injury position and shape.

a-b. The gradient of ATP burst (in ΔF/F0) with distance over injury (n = 13 mice). c. Changes of ATP burst (ΔF/F0) at indicated time points after FLA. d. The alignment of FLA centers (red) with Inflare gradient centers recorded prior to the FLA (−FLA, gray) (n = 14 mice). e. The mismatch distance between Inflare gradient centers and FLA centers. The Inflares recorded prior to FLA (−FLA), after FLA (+FLA) or random generated signals with same frequency (Random) are analyzed. Mismatches less than 100 μm are defined as success, and the success rate of each group is labeled (n = 14 mice for each group). f. Left, comparison of gradients that integrated Inflares over indicated time periods. Right, the relationship between gradient robustness (mismatch of gradient center with FLA center) and integration time. g-h. Inflare gradients with the alteration of injury shapes (n = 5/14/5 mice for gradient A.R, n = 5/5/5 mice for gradient α, respectively). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The cellular source of Inflares.

a. Illustration of experiments in which astrocytes were locally ablated by HSV-TK expression and GCV application (-Ast.I), and FLA-evoked Inflares were recorded by neuronal-expressed ATP1.0 sensors. The HSV-TK expressing mice with saline injection were used as controls (Vehicle). b. Different cell types in Vehicle or -Ast. I mice (n = 3 mice). c. Inflares in Vehicle or astrocyte-ablated mice (-Ast.I) (n = 6 mice). d-f. Similar as (a-c), except astrocytes were ablated by injection of gliotoxin L-αAA (-Ast.II). Mice with saline injection were used as controls (Vehicle) (n = 3 mice for staining; n = 6 mice in Vehicle and n = 7 mice in -Ast.II for recording). g–i. The immunofluorescence images and FLA-evoked Inflares in mice with local ablation of neurons by taCaspase3 (Casp3). The specificity is quantified as the colocalization of mCherry with NeuN. Mice with mCherry expression were used as controls (n = 3 mice for staining; n = 5 mice in mCherry and n = 4 mice in Casp3 for recording). j–l. The immunofluorescence images and FLA-evoked Inflares in mice with neuron inhibition. Mice injected with CNO without neuronal hM4Di expression (−hM4Di) were used as controls (n = 3 mice for staining; n = 4 mice for recording). m-o. The immunofluorescence images and FLA-evoked Inflares in mice with microglia depletion by BLZ945. Mice fed with normal food (Vehicle) were used as controls (n = 3 mice for staining; n = 8 mice in Vehicle and n = 9 mice in BLZ945 for recording). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Inflares depend on astrocytic Ca2+ signaling.

a. The expression (left) and fluorescence response (right) of ATP1.0 sensor (green) and jRGECO1a (red) co-expressed in astrocytes in vivo. b. The maximum spatial coverage (left) and average propagation speed (right) of ATP burst and astrocytic Ca2+ wave after injury (n = 10 slices from 4 mice). c, d. The ATP-dependency of FLA-evoked astrocytic Ca2+ wave, with its maximum propagation size (left), integration of fluorescence changes (middle) and propagation speed (right) analyzed (n = 10/3/5 slices from 4/2/3 mice for ACSF, apyrase and PPADS + Suramin). e-g. The gap-junction dependency of FLA-evoked astrocytic Ca2+ wave (f) and ATP bursts (g) (n = 10/9/7 slices from 4/4/3 mice for ACSF, 1-Octanol and CBX). h. FLA-evoked Inflares with gap-junction blockers (n = 10/9/7 slices from 4/4/3 mice for ACSF, 1-Octanol and CBX). i, j. Co-expression of hM3Dq (magenta) and ATP1.0 (green) in astrocytes for chemogenetic activation by CNO (n = 4 mice). k, l. Inflares in hM3Dq-expressing or control (−hM3Dq) slices with CNO application (n = 7 slices from 3 mice). m. CNO-evoked Inflares in hM3Dq-expressing slices bathed with PBN (n = 4 slices from 2 mice). n, o. Analysis of the colocalization of ATP and Ca2+ signals in mice co-expressing ATP1.0 and jRGECO1a in astrocytes. p. Left, alignment of Inflares peak and its corresponding Ca2+ signals. Right, the pie graph showing the distribution of Inflares that are either paired or non-paired with simultaneous Ca2+ elevation (n = 421 Inflares). Scale bars, 50 µm, except 5 µm in (j) (bottom). Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Inflares depend on astrocytic Panx1 hemichannels.

a. Illustration of Panx1 knockdown (KD, up), or knockout (KO, bottom) in Cas9-expressing mice. Scrambled shRNA or sgRNA were used as control. b, c. FLA-evoked Inflares in scrambled-shRNA-expressing (control) or Panx1 knockdown (Panx1 KD) mice (n = 5 and 3 mice for the control and Panx1 KD). d, e. Similar as (b-c), except Inflares were recorded in Panx1-sgRNA expressing Cas9 mice (Panx1 KO) or scrambled-sgRNA expressing Cas9 mice (control) (n = 6 and 4 mice for control and Panx1 KO). f. The size (left) and persistence (right) of FLA-evoked ATP burst in slices treated with ACSF, thapsigargin (TG), PBN, DCPIB or Clodronate (n = 10/11/7/9/7 slices from each group from n = 3 mice). g. Similar as (f), except the ATP burst in different genetic manipulations are analyzed (n = 6 mice for scrambled-sgRNA mice; n = 9 mice for astrocytic Panx1 knockout mice; n = 5 mice for astrocytic Panx1 OE mice; n = 5 mice for neuronal Panx1 knockout mice). h, i. The astrocytic Ca2+ wave in ACSF-treated, PBN-treated slices or slices from astrocytic Panx1 knockout mice (cKO) (n = 10/4/4 slices from 4/2/2 mice for ACSF, PBN and cKO). j-m. The Panx1 protein expression in astrocytes (Ast., up) and neurons (Neu., bottom) in each experimental condition (n = 18/30/16/29 cells from each group from n = 2 mice). Scale bars, 50 µm for (b) (d) and (h), and 10 µm for (j-m). Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Inflares drive changes in microglia states.

a. Schematic of experimental design in which total Inflares (II) or persistent Inflares (III) were abolished in vivo. ACSF injection was used as control (I). b. The injury diameter in each group (n = 10/5/5 mice in I, II and III). c, d. The microglia morphology in different groups in Cx3cr1GFP mice (n = 10/5/5 mice in I, II and III group, respectively). e. The FLA-evoked microglia migration in ACSF, apyrase (Apy) or inactivated apyrase (Ina. Apy) injected mice (n = 10/5/3 mice in ACSF, apyrase and inactivated apyrase group). f. Local extension of microglia processes (tdtomato, magenta) towards an Inflare (ATP1.0, green). g. The distance of each microglia process towards the Inflare center before and after the occurrence of an Inflare (n = 21/20 microglia). h, i. Microglia morphology (Iba1, cyan) in saline or PBN-injected mice, or in astrocytic Panx1 knockout mice (Ast. Panx1−/−, cKO) (cell volume: n = 58/6 cells/mice in saline, PBN and cKO; others: n = 63/6, 55/6 and 40/5 cells/mice in each group). j. The microglia (Iba1, cyan) phagocytosing apoptotic cells (TUNEL, magenta) in wild type (WT) or Ast. Panx1−/− (cKO) mice at 8 h after FLA. The Selected microglia are zoomed in with their phagocytosis states annotated as positive (+) or negative (−). k. Left, the 3D image showing the pouch of microglia process surrounding the apoptotic cell. Right, quantification of phagocytosis capacity at 8 h after FLA in WT and cKO mice. The phagocytosis capacity is defined as the percentage of microglia which are phagocytosing (n = 5 mice). l. Colocalization of lysosome marker (CD68, magenta) with microglia in WT or cKO mice at 8 h after FLA (n = 5 mice). Scale bars, 50 µm in (h, j, up), and 10 µm in (f, i) and reconstructed cells in (h, j, bottom). Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Inflares affect injury-induced transcriptional changes and cell apoptosis.

a. Expression profiling of injury-related genes (up) and enrichment analysis of inflammatory pathway gene (bottom) between saline and PBN-injected mice (left), or between wild type (WT) and astrocytic Panx1 knockout (cKO) mice 24 h after FLA (n = 3 mice). b. The expression level of inflammatory-related genes 24 h after FLA by real-time quantitative PCR, between saline- and PBN-injected mice (up), or between WT and cKO mice (bottom) (n = 6 mice). c. The apoptotic cells (TUNEL+, red) in saline or PBN-treated mice at 8 h after FLA (n = 6 mice). d. The protein level of cleaved caspase-3 (C-Casp3) and caspase-3 (Casp3), in saline or PBN-treated mice at 8 h after FLA (n = 6 mice). Quantitative comparison of C-Casp3 and Casp3 sample from same blot. The β-actin was used as the internal control from same experiments. e. Number of apoptotic cells (C-casp3+) at 8 hours after FLA, in control (Vehicle) or microglia-depleted (−Mic.) mice treated with saline or PBN (n = 5/4 mice in Vehicle and −Mic. group). Scale bars, 50 µm in (c). Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

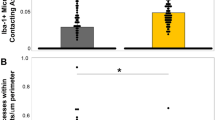

Extended Data Fig. 10 Knocking out astrocytic Panx1 shows protective effect for ischemic stroke in mice.

a. The consequence of Inflare blockage by astrocytic Panx1 knockout on MCAO outcome. The AAV-PHP. eB with astrocytic expressing of mCherry or cre was orbitally injected into the Panx1flox/flox mice for whole brain astrocytic Panx1 knockout. b. The brain infarction in Sham, flox mice with MCAO (M-flox) or astrocytic Panx1 knockout mice with MCAO (M-cKO) at 3 days after surgery, p = 0.027 between M-flox and M-cKO. c. The neurological deficient scores in different groups at 3 days after surgery (n = 3 mice for Sham; n = 4 mice for M-flox; n = 5 mice for M-cKO). d. The trajectory of mice (left) and total movement distances (right) in the open field test over 5 minutes (n = 3 mice for Sham; n = 4 mice for M-flox; n = 5 mice for M-cKO). e. The total time that mice maintained on the balance beam (n = 3 mice for Sham; n = 4 mice for M-flox; n = 5 mice for M-cKO). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; All statistical tests are two-sided and see Supplementary Table 1 for statistics.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Statistical Methods and Results.

Supplementary Video 1

The in vivo recording of FLA-evoked ATP dynamics by ATP1.0 sensor expressed in astrocytes. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Supplementary Video 2

The in vivo recording of Inflares at 12 h after ischemic stroke in mice. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical Source Data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Luan, P., Liu, J. et al. Spatiotemporally selective astrocytic ATP dynamics encode injury information sensed by microglia following brain injury in mice. Nat Neurosci 27, 1522–1533 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01680-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01680-w

This article is cited by

-

Astrocytes release ATP/ADP and glutamate in flashes via vesicular exocytosis

Molecular Psychiatry (2025)

-

State of the art indicators for imaging purinergic dynamics in vitro and in vivo

Purinergic Signalling (2025)

-

In vivo imaging in mouse spinal cord reveals that microglia prevent degeneration of injured axons

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Microglia contribute to neuronal synchrony despite endogenous ATP-related phenotypic transformation in acute mouse brain slices

Nature Communications (2024)