Abstract

We sought to identify long-term associations of medical complications and healthcare utilization related to polypharmacy following spinal surgery for degenerative lumbar pathology. The IBM MarketScan dataset was used to select patients who underwent spinal surgery for degenerative lumbar pathology with 2-year follow-up. Regression analysis compared two matched cohorts: those with and without polypharmacy. Of 118,434 surgical patients, 68.1% met criteria for polypharmacy. In the first 30 days after discharge, surgical site infection was observed in 6% of those with polypharmacy and 4% of those without polypharmacy (p < 0.0001) and at least one complication was observed in 24% for the polypharmacy group and 17% for the non-polypharmacy group (p < 0.0001). At 24 months, patients with polypharmacy were more likely to be diagnosed with pneumonia (48% vs. 37%), urinary tract infection (26% vs. 19%), and surgical site infection (12% vs. 7%), (p < 0.0001). The most prescribed medication was hydrocodone (60% of patients) and more than 95% received opioids. Two years postoperatively, the polypharmacy group had tripled overall healthcare utilization payments ($30,288 vs. $9514), (p < 0.0001). Patients taking 5 or more medications concurrently after spinal surgery for degenerative lumbar conditions were more likely to develop medical complications, higher costs, and return to the emergency department.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As many as 60–85% of older adults experience persistent musculoskeletal pain1,2, with 50–70% of those specifically attributed to chronic back pain3,4,5,6. Further, back pain is associated with functional limitation, mental health issues like depression, lower quality of life7,8 and is a leading cause of disability worldwide9. Typically, over-the-counter agents such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or topical analgesics are considered first-line treatments of low back pain10. However, patients with high pain severity are often prescribed narcotics like opioids which may provide short-term improvements in pain and function in the acute setting11,12. Polypharmacy, defined as the concurrent use of 5 or more medications, is associated with increased adverse events, drug-drug interactions, hospitalization and medical costs, especially in older adults13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Notably, the incidence of polypharmacy has doubled in the United States in recent years, partly due to the aging population and increased national comorbid status19,20. Also, certain mechanical pathologies may predispose to chronic low back pain21 as those with lumbar stenosis and degenerative disc disease have a higher incidence of low back pain lasting over 3 months8,22. Opioids and antispasmodic agents such as baclofen are commonly used for patients with chronic low back pain and spasticity, and these medications hold significant side effect profiles with risk of drug-drug interactions for older adults23,24.

Patients with lumbar stenosis and spondylosis requiring spine surgery are also often prescribed medications postoperatively11. Surgery for lumbar degenerative disorders is associated with significantly higher numbers of total drugs and pain relief medications—most frequently muscle relaxants and opioid analgesics20—than other surgery groups25.

Despite numerous studies demonstrating the adverse effects of polypharmacy16,26, there is limited understanding of the long-term consequences associated with polypharmacy in lumbar spine degeneration and postoperative course27. This study aims to address a gap in knowledge regarding specific adverse effects, hospitalization outcomes, and cost of care related to polypharmacy in patients undergoing spinal surgery for degenerative disc disease. Specifically, we compare long term sequelae of patients with spinal degeneration, including spinal stenosis, spondylosis, or disc herniation after undergoing lumbar decompression versus decompression with fusion. Primary outcomes include six-month, one-year, and two-year postoperative medical complications related to polypharmacy following spinal surgery for degenerative lumbar pathology. Secondary outcomes include categories and frequency of medications used, postoperative healthcare visits, medication refills, and cost of care.

Methods

Data source

Merative MarketScan Research Database, records of 2000–2021, was used for this study. MarketScan is a healthcare research insurance claims-based database that contains data for more than 265 million individuals from employer-sponsored plans. It includes data from healthcare use over time tracked with claim codes along with demographics, insurer and payments28. We have a neurological and neurosurgical custom database with inpatient, outpatient and prescription data. All methods were carried out in accordance with appropriate and relevant guidelines and regulations; the retrospective experimental protocol was approved by the University of Louisville Research Internal Review Board (IRB). Informed consent was waived by University of Louisville Research Internal Review Board (IRB) given the deidentified retrospective health claims database study design. Each included individual has a unique identifier that is used to link different services allowing longitudinal health services research studies.

Patient selection

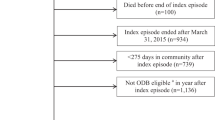

Adult patients (18 years or older) with lumbar spine degeneration (spinal stenosis, disk herniation, protrusion, and degeneration, Supplemental Table 1) who underwent surgery (fusion with or without decompression, Supplemental Table 2) were selected from inpatient admission data. International Classification of Disease 9th (prior to October 2015) and 10th revisions (October 2015 and after) and Current Procedural Terminology 4th edition (CPT-4) codes were used to identify conditions and surgical treatment. The first occurrence was set as the index hospitalization and the beginning of follow up in the data. Only those with continuous insurance enrollment for more than 1 year look back from index admission date and more than 2 years follow up from index discharge date were included. Those diagnosed with cancer in the year leading to the index hospitalization were excluded. The inclusion/exclusion process is detailed in Fig. 1.

Pre-index look-back time and post-index follow-up time

Pre index look-back time was calculated as the difference between the insurance start enrollment date and index hospitalization admission date. If the start enrollment date was not available (0.2% of cases), the first claim date was used instead. Post index follow-up time was calculated as the difference between the index hospitalization discharge date and the insurance end enrollment date. If the end enrollment date was not available (0.3% of cases), the last claim date in the data set was used.

Polypharmacy measure

The medications used in the follow up period (2 years post discharge from the index hospitalization) were checked to determine polypharmacy. The total number of medications used by the individuals in the included cohort was very large (> 8000), therefore, only medications in the top 75th percentile were checked. Polypharmacy was defined as the use of five or more different, concomitant medications at any time during the study period29. Two comparative groups were formed: polypharmacy vs. no polypharmacy. The no polypharmacy group was considered a control group.

Patient characteristics

Patients’ characteristics include demographics (age, gender), insurance type (commercial, Medicaid or Medicare), comorbidities (Elixhauser comorbidity score obtained using used the adaptation to ICD-9-CM codes developed by Quan et al.30), and spine degeneration type. All patient characteristics were noted at the index hospitalization.

Outcome of interest

We examined length of stay (LOS), total payments, and home discharge during the index hospital stay. We also evaluated hospital readmission, outpatient services, outpatient medication refills, emergency room visits, and associated payments, along with the incidence of complications (acute kidney injury, surgical site infection, cardiac arrest, deep vein thrombosis, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, stroke, wound dehiscence, Supplemental Table 3), mental health (depression, anxiety, Supplemental Table 4), and opioid use (Supplemental Table 5) within 30 days, 6-, 12- and 24- months of index hospitalization discharge. Payments were adjusted to 2021 US dollars using the medical component of the consumer price index (accessible through the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics website, www.bls.gov.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized median ± median absolute difference (MAD) as they were all found to be non-normally distributed per the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical variables were summarized with percentages. Individual characteristics were compared using Brown Mood test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. To account for differences in characteristics between the 2 analysis groups, regression analysis was used to compare outcomes. The regression models included polypharmacy (yes/no) as the test variable and all the characteristics, age (continuous), gender (male/female), insurance (commercial/Medicaid/Medicare), and Elixhauser comorbidity score (0, 1, 2, 3 or more), as control independent variables. Quantile regression was used for continuous variables which were summarized with adjusted median ± MAD. Logistic regression was used for categorical variables which were summarized with adjusted probabilities. To account for multiple testing, the Bonferroni31,32p-value correction was used and the significance level was set to 0.0004 (= 0.05/132 outcome comparisons). All tests were 2-sided. We used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) for data statistical analysis.

Results

Patient population

A total of 118,434 patients with degenerative spine disease (Table 1) receiving spinal surgery were included.

Of these patients, 80,752 met criteria for polypharmacy (68.1%), and 41% of those were diagnosed with spinal stenosis, 34% with disc herniation, and 24% with disc protrusion. Patients with spinal stenosis and disc protrusion were more likely to be taking 5 or more medications than those with disc herniation (p < 0.0001). Polypharmacy was more likely observed in older patients (median age 58 vs. 52 years, p < 0.0001), females (55% vs. 47%, p < 0.0001), and Medicare users (30% vs. 14%, p < 0.0001). More patients in the polypharmacy group had medical comorbidities with higher Elixhauser of 3 or more (12% vs. 10%, p < 0.0001). Subgroup analyses included those who received spinal fusion (n = 61,087) with 44,411 in the polypharmacy group and 16,676 non-polypharmacy group as well as decompression alone (n = 95,657) with 64,748 in the polypharmacy group an 30,909 without polypharmacy.

Index hospitalization and discharge disposition

The regression adjusted length of hospital stay (accounting for specific comorbidities for patients with polypharmacy patients was 2.4 days and 1.4 days for non-polypharmacy patients (p < 0.0001), and median index hospital payments were higher for the polypharmacy group ($29,348) versus the non-polypharmacy group ($23,388) (p < 0.0001). Fewer patients with polypharmacy were discharged home compared to patients of the non-polypharmacy cohort (81% vs. 80%, p = 0.0205) (Table 2).

Health outcomes and complications

Postoperative outcomes of index hospitalization, 30 days, 6, 12, and 24 months are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

During index hospitalization, pneumonia 5% and 4% in the non-polypharmacy group (p < 0.0001) and surgical site infection was present in 1% of patients with polypharmacy versus 0% in non-polypharmacy (p = 0.0118).

In the first 30 days after discharge, surgical site infection was observed in 6% of those with polypharmacy and 4% of those without polypharmacy (p < 0.0001), DVT was shown in 3% in polypharmacy and 2% of non-polypharmacy (p < 0.0001), urinary tract infection in 4% for the polypharmacy group versus 3% without polypharmacy (p < 0.0001), and acute kidney injury was found in 4% for polypharmacy and 3% in non-polypharmacy (p = 0.0219), Table 3. At least one complication was observed in 24% for the polypharmacy group and 17% for the non-polypharmacy group (p < 0.0001).

At 6 months, patients with polypharmacy were more likely to be diagnosed with pneumonia (19% vs. 14%), surgical site infection (8% vs. 5%), deep vein thrombosis (6% vs. 4%), stroke 3% vs. 2%), pulmonary embolism (2% vs. 1%), myocardial infarction (2% vs. 1%), (p < 0.0001), Table 4.

At 24 months, 48% with polypharmacy had pneumonia compared to 37% without polypharmacy (p < 0.0001), urinary tract infection was seen in 26% of those with polypharmacy versus 19% without polypharmacy, surgical site infection was seen in 12% of those with polypharmacy and 7% in the non-polypharmacy group (p < 0.0001), 10% with polypharmacy had DVT versus 5% without polypharmacy (p < 0.0001), 8% with polypharmacy had stroke versus 5% without polypharmacy, myocardial infarction was observed in 5% with polypharmacy versus 2% without polypharmacy. Depression (48% vs. 31%), anxiety (43% vs. 29%) and adverse drug events (8% vs. 4%) were also associated with those meeting criteria for polypharmacy compared with those who did not have concurrent polypharmacy at 6 months postoperatively (p < 0.0001). At 24 months, opioid use disorder was observed in 20% of those with polypharmacy versus 14% of those in the non-polypharmacy group (p < 0.0027).

Common medication prescriptions

The most commonly prescribed medication was hydrocodone in 60% of patients, with 95% of patients receiving any opioid medication, Table 5.

Gabapentin was the third most prescribed medication at 34% followed by methylprednisolone (30%) and azithromycin (27%). Cyclobenzaprine was the most common antispasmodic agent at 25%. The second most common medication class was muscle relaxants, prescribed to 64% of patients, followed by NSAIDs (60%) and antidepressants (54%).

Healthcare utilization and payments

Patients with polypharmacy were more likely to go to the emergency room and to be admitted at the hospital at six, twelve, and 24 months (p < 0.0001). Median payments for index hospital admission at time of surgery were $29,348 for those with polypharmacy and $23,388 for the non-polypharmacy group (p < 0.0001) with higher LOS associated with the polypharmacy group (2.4 versus 1.8 days) (p < 0.0001). The number of outpatient services utilized and their payments were higher for patients with polypharmacy at 6, 12, and 24 months (p < 0.0001). Polypharmacy patients were also more likely to request medication refills (p < 0.0001) and had higher prescription drug payments for all evaluated time points (p < 0.0001). The overall combined payments (Table 2) for inpatient and outpatient services and prescription medications six months after initial hospitalization discharge were $2,310 for non-polypharmacy patients compared to $6523 for polypharmacy patients (p < 0.0001). At 12 months after discharge, polypharmacy patients paid a combined median amount of $13,804 compared to $4,561 for the controls (p < 0.0001). 24 months after initial hospitalization discharge, polypharmacy patients paid a median combined amount of $30,288 compared to $9,514 for non-polypharmacy patients (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In the present study, 68% of patients undergoing spinal surgery for lumbar degenerative pathology met criteria for polypharmacy (taking 5 or more medications concurrently) and were more likely to incur complications such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, surgical site infection at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. Over 95% of patients were prescribed opioids (the leading medication category prescribed) and almost half were prescribed antispasmodics with cyclobenzaprine as the most commonly used at 25%. Patients meeting criteria for polypharmacy were also more likely to utilize outpatient services, visit the emergency room, and become readmitted, thereby incurring higher costs than their counterparts even 2 years post initial discharge. At two years follow-up, the polypharmacy group had tripled overall healthcare utilization payments.

Between 2000 and 2012, the incidence of polypharmacy has almost doubled in the United States20. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), 1 in 5 US adults between 40 and 79 years old used at least 5 prescription drugs in 201933. The rise in polypharmacy may be attributed to the aging population, as those over the age of 65 years are more likely to be prescribed multiple medications for chronic diseases20,34,35,36,37. Additionally, the rise in obesity and mental health disorders likely contribute to this increasing trend18,38. Anxiety and depression were more likely to be observed in those taking 5 or more medications concurrently in the present study.

Polypharmacy is associated with a host of dangerous drug-drug interactions and altered pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics as patients age leading to adverse drug events and medical complications24,37,39,40. Inappropriate medication use in older adults has been reported to exceed 60%26. The inherent risk of adverse medical outcomes from side effect profiles and medication non-compliance13,14,34,41,42 has been shown to increase hospitalization and medical costs for the elderly up to 30%15. Opioid use was most common in those with polypharmacy following lumbar surgery, despite the trend that preoperative opioid dependence decreases after spinal surgery43,44,45.

It is likely that patients with polypharmacy have poorer health status at baseline or post-injury and are disproportionally at risk of medical complications. However, despite regression-controlled analyses for comorbidities we saw increased risk of postoperative complications. One of the largest discrepancies for the polypharmacy cohort was observed in relation to postoperative pneumonia. Opioids and benzodiazepines are associated with increased risk of pneumonia secondary to immunosuppressive effects and possibly respiratory depression46. Dublin and colleagues report that the odds for pneumonia was more than 200% higher (OR 3.24) in individuals newly prescribed opioids and almost 100% higher (OR 1.88) regardless of time of use46. Additionally, surgical site infection during index hospitalization, the first 30 days post-discharge, and a seemingly compounding effect across 2 years. SSI is associated with 3–5% of lumbar surgery cases47 and higher healthcare utilization48,49. Many studies have shown that smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension represent significant risk factors for development of SSI50. Polypharmacy may also represent an indirect risk factor to signal to clinicians an increased risk associated with early and late SSI.

Chilakapati et al. showed that preoperative polypharmacy was associated with increased readmission within 90-days of a corrective spinal deformity surgery in adults51. Older adults in the polypharmacy cohort had a higher rate of readmission within the 90-day window. Our study extends the follow up timeline and demonstrates an increased risk of readmission even at 2 years post-operation. Sato et al. investigated 767 patients 65 or older retrospectively who underwent knee arthroplasty, hip arthroplasty or spine surgery for degenerative conditions25 and found that greater than 50% of these patients were taking 6 or more prescription medications.

Despite a scarcity of literature assessing the long-term effects of polypharmacy in spinal degenerative surgery, there is relatively more research in other surgical fields on the effects of polypharmacy. In 2016, Harstedt et al. found that polypharmacy was predictive of rehospitalization in a case review of 272 patients with hip fracture who underwent acute total hip arthroplasty17. Similarly, Holden et al. found that patients over the age of 60 undergoing bilateral transfer abdominus release for ventral hernias were more likely to suffer complications, postoperative delirium, increased hospital LOS, and cardiac events if they engaged in polypharmacy52. In a retrospective series of 584 patients who underwent abdominal surgery, Abe et al. found that polypharmacy was a strong predictive factor for prolonged hospitalization53. Arends et al. investigated 518 patients above the age of 70 undergoing cardiac surgery to analyze the association between preoperative medication use and functional decline post-surgery54. They found that preoperative polypharmacy was associated with higher risks of functional decline (defined as either disability or a decreased health-related quality of life) after cardiac surgery. Our results corroborate these findings of increased complications associated with polypharmacy postoperatively following spine surgery. In 2020, Cadel et al. conducted a systematic review on polypharmacy in patients with spinal cord injuries27 and found that negative clinical outcomes such as drug-related issues and bowel complications were associated with polypharmacy27. Kitzman et al. designed a retrospective case-control study in 2016 to analyze the association of polypharmacy and spinal cord injury29 and found that patients with spinal cord injuries were prescribed multiple medications and most from drugs with high rates of toxicity or adverse effects. Our analysis found that polypharmacy in spinal degeneration was associated with more postoperative complications.

Nazemi et al. published a literature review in 2017, evaluating studies and systematic reviews published between 1990 and 2015, to create an algorithm for preventing and managing delirium in geriatric patients who undergo elective spinal surgery55. They found that polypharmacy is an independent risk factor for delirium which can increase length of hospital stay to greater than 7 days. Polypharmacy is a well-described risk factor for delirium, especially in older adults56,57. Additionally, other studies have described an increased risk of dementia diagnosis—another risk factor for delirium—following spinal surgery with associated increased healthcare utilization58,59. However, a prospective study conducted on 250 patients with an average age of 72 years in Thailand demonstrated that there was no significant association between polypharmacy and post-operative cognitive decline60.

Strengths and limitations

The degree to which polypharmacy contributed to increased risk of medical complication in patients with likely higher degree of pre-existing medical comorbidities is uncertain. We cannot conclude a causal relationship of polypharmacy to complications observed. However, a strength of the analysis is the large sample size that demonstrates clinical trends across populations. One limitation of this study includes consistent charting of “polypharmacy” with multiple accepted definitions in the literature. The definition of polypharmacy varies by providers and authors, and does not always specify whether the discussion is limited to prescription or non-prescription drugs only and what specific categories those drugs fall into, for example. Future studies may specifically analyze categories of drugs and how they affect long-term outcomes61. Another limitation includes the use of paid claims data such that variation in diagnosis and severity of postoperative complications may be reported. As other claims databases, results should be interpreted and generalized cautiously especially considering that billing codes are also prone to human error. Even so, the MarketScan Research Database allows users to follow patients long-term and appreciate their postoperative course and quality of life. Future studies may also examine ways in which enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols with multimodal pain management strategies may reduce risk of postoperative polypharmacy62.

Conclusion

Opioids were the most commonly prescribed drugs for those meeting criteria of polypharmacy, observed in more than 95% of patients. Notably, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and surgical site infection were observed at higher rates postoperatively for those with polypharmacy that increased across 24 months. Patients taking 5 or more medications concurrently after spinal surgery for degenerative lumbar conditions were more likely to develop medical complications across two years after surgery and return to the emergency department and utilize more outpatient services than non-polypharmacy counterparts.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Welsh, T. P., Yang, A. E. & Makris, U. E. Musculoskeletal Pain in older adults: A clinical review. Med. Clin. North. Am. 104, 855–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2020.05.002 (2020).

Bressler, H. B., Keyes, W. J., Rochon, P. A. & Badley, E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly. A systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 24, 1813–1819. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199909010-00011 (1999).

Palmer, K. T. & Goodson, N. Ageing, musculoskeletal health and work. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 29, 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2015.03.004 (2015).

Woolf, A. D. & Pfleger, B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull. World Health Organ. 81, 646–656 (2003).

Podichetty, V. K., Mazanec, D. J. & Biscup, R. S. Chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain in older adults: clinical issues and opioid intervention. Postgrad. Med. J. 79, 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.79.937.627 (2003).

Patel, K. V., Guralnik, J. M., Dansie, E. J. & Turk, D. C. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging trends Study. Pain. 154, 2649–2657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.029 (2013).

Rudy, T. E., Weiner, D. K., Lieber, S. J., Slaboda, J. & Boston, R. J. The impact of chronic low back pain on older adults: A comparative study of patients and controls. Pain. 131, 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.012 (2007).

Rundell, S. D. et al. Predictors of persistent disability and back pain in older adults with a new episode of care for back pain. Pain Med. 18, 1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw236 (2017).

Vos, T. et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 380, 2163–2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 (2012).

Peck, J. et al. A comprehensive review of over the counter treatment for chronic low back pain. Pain Ther. 10, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00209-w (2021).

Schoenfeld, A. J. & Weiner, B. K. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: evidence-based practice. Int. J. Gen. Med. 3, 209–214. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.s12270 (2010).

Chaparro, L. E. et al. Opioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD004959 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub4 (2013).

Frazier, S. C. Health outcomes and polypharmacy in elderly individuals: An integrated literature review. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 31, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.3928/0098-9134-20050901-04 (2005).

Nguyen, J. K., Fouts, M. M., Kotabe, S. E. & Lo, E. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in geriatric nursing home residents. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 4, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.03.002 (2006).

Akazawa, M., Imai, H., Igarashi, A. & Tsutani, K. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 8, 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.03.005 (2010).

Dagli, R. J. & Sharma, A. Polypharmacy: A global risk factor for elderly people. J. Int. Oral Health. 6, i–ii (2014).

Harstedt, M., Rogmark, C., Sutton, R., Melander, O. & Fedorowski, A. Polypharmacy and adverse outcomes after hip fracture surgery. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 11, 151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-016-0486-7 (2016).

Onder, G., Marengoni, A. & Polypharmacy JAMA 318, 1728, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.15764 (2017).

Masnoon, N., Shakib, S., Kalisch-Ellett, L. & Caughey, G. E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 17, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2 (2017).

Kantor, E. D., Rehm, C. D., Haas, J. S., Chan, A. T. & Giovannucci, E. L. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999–2012. JAMA. 314, 1818–1831. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13766 (2015).

Will, J. S., Bury, D. C. & Miller, J. A. Mechanical low back pain. Am. Fam Physician. 98, 421–428 (2018).

Wong, A. Y. L., Karppinen, J. & Samartzis, D. Low back pain in older adults: Risk factors, management options and future directions. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 12, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13013-017-0121-3 (2017).

Dietz, N., Wagers, S., Harkema, S. J. & D’Amico, J. M. Intrathecal and oral baclofen use in adults with spinal cord Injury: A systematic review of efficacy in spasticity reduction, functional changes, dosing, and adverse events. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 104, 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2022.05.011 (2023).

Corsonello, A., Pedone, C. & Incalzi, R. A. Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 571–584. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986710790416326 (2010).

Sato, K. et al. Prescription drug survey of elderly patients with degenerative musculoskeletal disorders. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 22, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14326 (2022).

Kwan, G. T., Frable, B. W., Thompson, A. R. & Tresguerres, M. Optimizing immunostaining of archival fish samples to enhance museum collection potential. Acta Histochem. 124, 151952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2022.151952 (2022).

Cadel, L. et al. Spinal cord injury and polypharmacy: a scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 42, 3858–3870. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1610085 (2020).

Hansen, L. IBM MarketScan research databases for life sciences researchers. IBM Watson Health (2018).

Kitzman, P., Cecil, D. & Kolpek, J. H. The risks of polypharmacy following spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 40, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772314y.0000000235 (2017).

Quan, H. et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care. 43, 1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 (2005).

Armstrong, R. A. When to use the bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 34, 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131 (2014).

Ranstam, J. Multiple P-values and Bonferroni correction. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24, 763–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2016.01.008 (2016).

Hales, C. M., Servais, J., Martin, C. B. & Kohen, D. Prescription drug use among adults aged 40–79 in the United States and Canada. NCHS Data Brief., 1–8 (2019).

Halli-Tierney, A. D., Scarbrough, C. & Carroll, D. Polypharmacy: Evaluating risks and deprescribing. Am. Fam Physician. 100, 32–38 (2019).

Delara, M. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 22, 601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03279-x (2022).

O’Mahony, D. & Rochon, P. A. Prescribing cascades: we see only what we look for, we look for only what we know. Age Ageing. 51 https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac138 (2022).

Pietraszek, A. et al. Sociodemographic and Health-related factors influencing drug intake among the Elderly Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148766 (2022).

Slater, N., White, S., Venables, R. & Frisher, M. Factors associated with polypharmacy in primary care: A cross-sectional analysis of data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). BMJ Open. 8, e020270. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020270 (2018).

Midao, L., Giardini, A., Menditto, E., Kardas, P. & Costa, E. Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 78, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.018 (2018).

Fu, J. L. & Perloff, M. D. Pharmacotherapy for spine-related pain in older adults. Drugs Aging. 39, 523–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-022-00946-x (2022).

Lee, V. W. et al. Medication adherence: Is it a hidden drug-related problem in hidden elderly? Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 13, 978–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12042 (2013).

Hanlon, J. T. et al. Incidence and predictors of all and preventable adverse drug reactions in frail elderly persons after hospital stay. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 511–515. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.5.511 (2006).

Dietz, N. et al. Preoperative and postoperative opioid dependence in patients undergoing Anterior Cervical Diskectomy and Fusion for degenerative spinal disorders. J. Neurol. Surg. Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 82, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718759 (2021).

Sharma, M. et al. Impact of Surgical approaches on complications, Emergency Room Admissions, and Health Care Utilization in patients undergoing lumbar fusions for degenerative disc diseases: a MarketScan Database Analysis. World Neurosurg. 145, e305–e319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.10.048 (2021).

Dietz, N. et al. Cannabis Use Disorder trends and Health Care utilization following cervical and lumbar spine fusions. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000004874 (2023).

Dublin, S. et al. Use of opioids or benzodiazepines and risk of pneumonia in older adults: A population-based case-control study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59, 1899–1907. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03586.x (2011).

Zhou, J. et al. Incidence of Surgical site infection after spine surgery: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 45, 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003218 (2020).

Dietz, N. et al. Health Care utilization and Associated Economic Burden of Postoperative Surgical Site infection after spinal surgery with Follow-Up of 24 months. J. Neurol. Surg. Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 84, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1720984 (2023).

Dietz, N. et al. Outcomes of decompression and fusion for treatment of spinal infection. Neurosurg. Focus. 46, E7. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.10.FOCUS18460 (2019).

Zhang, L. & Li, E. N. Risk factors for surgical site infection following lumbar spinal surgery: A meta-analysis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 14, 2161–2169. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S181477 (2018).

Chilakapati, S., Burton, M. D. & Adogwa, O. Preoperative polypharmacy in geriatric patients is Associated with increased 90-Day all-cause hospital readmission after surgery for adult spinal deformity patients. World Neurosurg. 164, e404–e410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.04.137 (2022).

Holden, T. R., Kushner, B. S., Hamilton, J. L., Han, B. & Holden, S. E. Polypharmacy is predictive of postoperative complications in older adults undergoing ventral hernia repair. Surg. Endosc. 36, 8387–8396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09099-9 (2022).

Abe, N. et al. Polypharmacy at admission prolongs length of hospitalization in gastrointestinal surgery patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 20, 1085–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14044 (2020).

Arends, B. C. et al. The association of polypharmacy with functional decline in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 88, 2372–2379. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15174 (2022).

Nazemi, A. K. et al. Prevention and management of postoperative delirium in elderly patients following elective spinal surgery. Clin. Spine Surg. 30, 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000467 (2017).

Hein, C. et al. Impact of polypharmacy on occurrence of delirium in elderly emergency patients. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 15 (850 e811-855). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.08.012 (2014).

Ranhoff, A. H. et al. Delirium in a sub-intensive care unit for the elderly: Occurrence and risk factors. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 18, 440–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324841 (2006).

Sharma, M. et al. Incidence of new onset dementia and health care utilization following spine fusions: A propensity score matching analysis. Neurochirurgie. 68, 562–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2022.07.010 (2022).

Sharma, M. et al. Trends and outcomes in patients with dementia undergoing spine fusions: A matched nationwide inpatient sample analysis. World Neurosurg. 169, e164–e170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.10.099 (2023).

Lertkovit, S. et al. Polypharmacy in older adults undergoing major surgery: Prevalence, Association with postoperative cognitive dysfunction and potential Associated Anesthetic agents. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 811954. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.811954 (2022).

Lee, S. W. et al. Opioid utility and hospital outcomes among inpatients admitted with Osteoarthritis and Spine disorders. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000002101 (2022).

Dietz, N. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for spine surgery: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 130, 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.181 (2019).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ND: writing the original draft of the manuscript, organizing the study; idea and generation, retrieved data, finalizing the manuscriptCK: writing the manuscript, organizing the study; retrieved dataAE: writing the original draft of the manuscript, organizing the study; retrieved data and supervised the studyMB: writing the original draft of the manuscript, organizing the study; idea and generation, retrieved data, finalizing the manuscriptKW: writing the original draft of the manuscript, organizing the study; retrieved data, finalizing the manuscriptAJ: writing the original draft of the manuscript, organizing the study; retrieved data, finalizing the manuscriptMS: statistics, supervision of the study, drafting manuscript (methods section)DW: statistics, supervision of the study, drafting manuscript (methods section)BU: statistics, supervision of the study, drafting manuscript (methods section)DD: organizing the study; retrieved data, finalizing the manuscript, supervision of the studyMB: organizing the study; retrieved data, finalizing the manuscript, supervision of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived by University of Louisville Research Internal Review Board (IRB) given the deidentified retrospective health claims database study design.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dietz, N., Kumar, C., Elsamadicy, A.A. et al. Polypharmacy in elective lumbar spinal surgery for degenerative conditions with 24-month follow-up. Sci Rep 14, 25340 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76248-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76248-6